“Making It Home: Life Lessons From

A Season of Little League”

The author:

Teresa Strasser

The publishing info:

Berkley Books/Penguin Random House

352 pages; $18

Released June 6, 2023

The links:

The publishers website

The authors website

At Bookshop.org

At Powells.com

At Vromans.com

At TheLastBookStoreLA

At Skylight Books

At Diesel Books

At Target

At BarnesAndNoble.com

At Amazon.com

The review in 90 feet or less

If we can ask without raising any suspicion: What in blue blazes ever happened to Yasiel Puig?

The quick-reference site Baseball-Reference notes that the now-31-year-old right fielder from Cienfuegos, Cuba who defected/was smuggled into the U.S. through Mexico, has no statistical evidence of playing anywhere in 2023.

The Dodgers, who signed him in 2012, saw him finish second in NL Rookie of the year in ’13, make the NL All-Star team in ’14, featured on the cover of “MLB The Show” video game in ’15, appears in the ’17 and ’18 World Series for them, and then … Poof. One can only be so patient. (We had advocated the Dodgers trade Puig to the Marlins for Giancarlo Stanton right around that ’15 season. Straight up. Stanton returns to SoCal, Puig goes to Cuba-adjacent Miami. It was a missed opportunity once Stanton hit 59 homers and drove in 132 runs during his last year with the Marlins, winning the NL MVP, then defecting to the Yankees).

Puig was traded to Cincinnati after ’18, was shipped to Cleveland in a Trevor Bauer deal, fell off the earth, navigated through the Dominican Winter League, the Mexican League and most recently, South Korea’s KBO.

Puig is/was really in a league of his own. And his own undoing. A March, 2022 story in the Korean Herald noted: Though he has gone 1-for-9 with three strikeouts in his first four games prior to Thursday, the Cuban slugger hasn’t seemed fazed by his sluggish performance. Earlier this week, Puig uploaded a video of himself dancing, maskless, in an alley in Itaewon, a popular nightlife district in Seoul, on Instagram. Puig was technically violating South Korea’s mask mandate at the height of the pandemic here. The country reported a record 621,328 COVID-19 cases Thursday morning, with an average of over 380,000 over the past seven days.

If he never plays again, he’ll go out a Hero. As in, his last team was the Kiwoom Heroes, where he hit .277 with 21 homers and 73 RBIs in 126 KBO games. If he’s deemed a villan, it’s because the last we heard from him involved a guilty plea to federal law enforcement regarding bets he placed with an illegal sports betting operation, but then he changed the plea to not guilty because of “significant new evidence.”

As his Wikipedia profile recalls, he was given the nickname “The Wild Horse” by Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully.

We think of him more as “Little League Puig.”

It created a more legitimate visual for us. Because whenever he hit the ball, it seemed he would not stop running until someone tagged him out. And whenever he caught the ball, he knew nothing of what a cut-off man was supposed to do, and overthrew him in an attempt to catch a runner trying to advance.

Sometimes it worked. Often, it didn’t. Live and learn. Like in Little League. Except Puig didn’t seem to do much of the second part.

A Little League Home Run (or LLHR in the scorebook) is something to behold, and Puig occasionally gave us those treats in a big-league uniform. You run and run and run until the defense gives up. It’s the ultimate example of faith that, somehow, you’ll make it home unscathed, and your teammates will celebrate your arrival.

Or, you won’t make it home, and your teammates will groan.

We dare recall a time in July of 2013 when Puig broke up a scoreless game in the bottom of the 11th inning by hitting the ball over the fence, flipping his bat, and sliding into home plate.

The story the next day in USA Today read: “Yasiel Puig had been relatively quiet since the All-Star break. We say relatively because he was still spectacular in the field and was hitting at an impressive clip, but hadn’t crushed a 600-foot home run while saving a baby from a burning building and simultaneously throwing out Sid Bream in the 1992 NLCS.

“After Sunday, he is quiet no more.”

Here’s the point (finally): When “Little League Puig” took the field, there was as much cringing as there was celebrating life. He didn’t know better. Or did he? It was open for discussion. Often, one couldn’t differentiate if Little Leaguers imitated Puig, or the opposite.

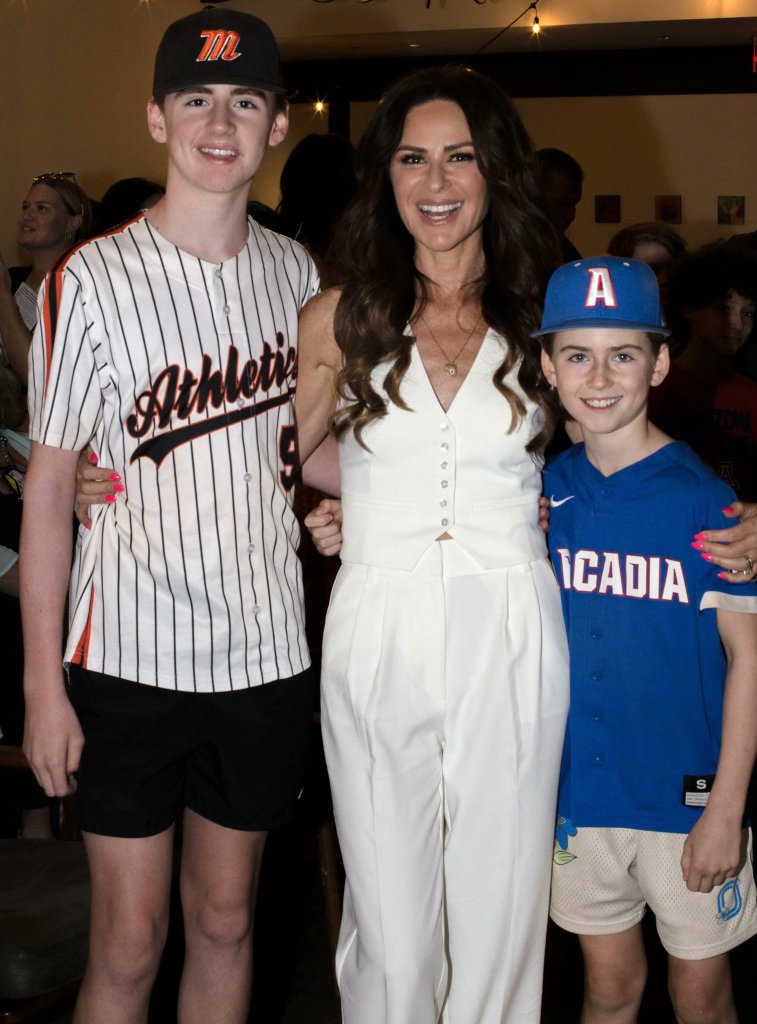

When Teresa Strasser and her father, Nelson, parked their lawn chairs down the first-base line to watch Teresa’s son play (under the managerial guidance of her husband, Daniel), there were cringe moments. But also celebrations of life. It was a reckoning of past ineptness in the parental lessons that were supposed to be passed down to the next generation.

Thanks to the framing of what they watched during the Little League season in Phoenix, the Purple Pinstripes, performing at the Ingleside Middle School diamond, provided the visual setting, but discussions of life and what things from the past meant were far more front and center.

The pace of a baseball game can allow for these meaningful conversations to take place on what can be common ground.

Sometimes books find us for this annual review series in a most delightful round-about sort of way. This is another great example, one best slotted in the biography/memoir category, but as the author points out on her Twitter feed, it’s far more about the intersection of baseball and grief.

It was a Q&A posted in USA Today the first week of June, just prior to its release that caught our eye. Which led to following the author on Twitter:

Which led to realizing this was the same person who had been co-hosting The Adam Carolla Show podcast.

Strasser has had plenty of experience finding her voice in her writing, and more than a decade ago she birthed “Exploiting My Baby: Because It’s Exploiting Me.” As happens in the business of media, it was optioned into a TV series and developed for a pilot.

The same could happen with this home run of a journey which doesn’t actually exploit her second son, but provides ample background noise for someone once included in an Arizona Republic list of the “Top Ten Social Media Moms” in 2015 (“funny, observant and consistently clever”) as well as the New York Post’s Page Six noting her inclusion in the 2003 amiannoying.com list of “Least Annoying People.” (And was in the top 300 for “Most Annoying” in 2007).

If you’ve read Strasser’s clippings from previous reviews and awards, she never fails to add self-effacing humor, off-the-wall wit and a well-placed curse word. She is made for the media of today.

The jumping off point for her this time is dealing with the reality that her brother has died after a battle with cancer, and her mom passes away four months later. Now, she’s dealing with her dad, who speaks baseball. She learns the language to communicate for a season-long therapy session.

The take away, without taking away any of the thunder that the book builds through its chapters of love and anguish, is this: “Baseball doesn’t promise you a happy ending, but it always leaves room for one.”

And life may also imitate baseball, but don’t be intimated by that.

So if someone like Yasiel Puig someday figures out the rules of the game and may want to come to the Dodgers’ camp as a non-roster invitee, who’s to say there won’t be a ending that brings us more joy and binges of cringing, which, as we learned, can co-exist.

An endearing excerpt

From pages 208-209:

Nate doesn’t exactly have command, but he’s throwing Little League fire this morning. He’s making the most of his long legs, so disproportionately long, his purple belt almost looks perched on his nipples. His front stride is landing closer to the mound this outing. He looks sure-footed and stable, despite hitting just outside the zone.

“There’s movement on the tail of the pitches,” my dad notices. “He just needs to throw strikes. These walks. You know. They have a way of coming in.”

“I know.”

“But he looks smooth tonight. That one outing where he was terrible? There was no continuity to his delivery. My heart stopped at the top of his motion, every pitch. It was like you threw something into the gears of a machine. This is like watching an opera.”

“I hate opera,” I say. “Don’t tell anybody.”

After walking two batters, Nate strikes out the next three. Inning over. Now Team Navy’s pitcher warms up.

“I’d rather watch this than Sandy Koufax himself,” says Dad, gesturing toward the diamond, where his grandson, after gathering himself, throws strikes. “‘And I saw Koufax at Dodger Stadium. Saw him strike out eighteen Giants.”

“You saw him strike out Willie Mays, right?”

“Koufax struck him out twice that night, the great Willie Mays. Mays led the league in home runs four times.”

“You call Wyatt Caleb, and you call Caleb Wyatt, but your mind has retained all this?”

“Oh, and I remember the great Vin Scully, announcer for — “

“I’ve heard of him — “

“The great Vin Scully, announcer for the Dodgers, he said you only get one Sandy Koufax in a lifetime.”

“He had arm troubles right?”

“Oh yeah. That game he struck out out eighteen, between innings he was rubbing hot pepper ointment on his arm and they were draining fluids from his elbow. He played right through it. In the crowd, it was like we were in a trance. We couldn’t believe it.”

“Did he have a cool baseball nickname?”

“‘Oh yeah. They called him the Left Arm of God. Too bad the arm gave out and God couldn’t fix it.”

“Speaking of throwing too many pitches, how many pitches did Nate throw that inning? I’m supposed to tell Daniel.”

He looks at the counter.

“I don’t know. I think I missed a couple.”

“You had one job. Give me that.” I grab the little clicker. “Well, somewhere around thirty. Isn’t that too many for one inning?”

“It’s not one-two-three, three up, three down,” Dad admits.

How it goes in the scorebook

The Hallmark Channel might not want to secure the rights to this one, but some brave network will see this has having all the hallmarks of a winning scripted series. Especially if Strasser is on the writing team driving the project. Maybe some striking writer from the guild can start working on a treatment during all this down time.

And if your daughter happened to mark Father’s Day by sending you a gift card to Powell’s Book Store near her home in Portland (as ours did), here’s the ink to spend in it. It’s pro-active therapy conversation.

You can look it up: More to ponder

== Strasser interviewed by the Arizona PBS outlet here. And an interview on MLB.com’s “High Heat here.

== Perhaps related in some way? Check out “Home Base: A Mother-Daughter Story,” a picture book geared to pre-schoolers by Nikki Tate (Holiday House, 32 pages, $8.99, released March 7, 2023, illustrated by Katie Kath). The mom is a bricklayer, the daughter plays baseball. Both are determined to get it right. But who are we kidding. There’s no cursing in this book. It’s not at all related. Wait 20 years and get back to us when you have some plot lines developed.

1 thought on “Day 18 of 2023 baseball books: Good grief is on a diamond not so rough”