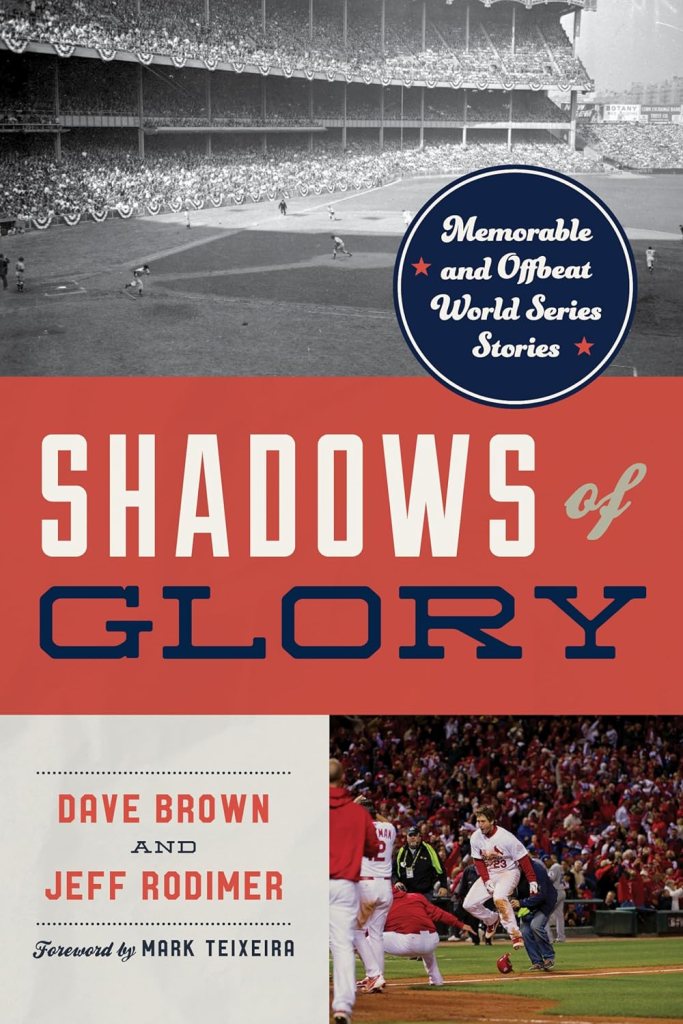

“Shadows of Glory: Memorable and

Offbeat World Series Stories”

The authors:

Dave Brown

Jeff Rodimer

The publishing info:

Lyons Press

314 pages, $26.95

Released April 2, 2024

The links:

The publishers website

The authors website

At Bookshop.org

At Powells.com

At Vromans.com; at {pages a bookstore}

At BarnesAndNoble.com; at Amazon.com

The review in 90 feet or less

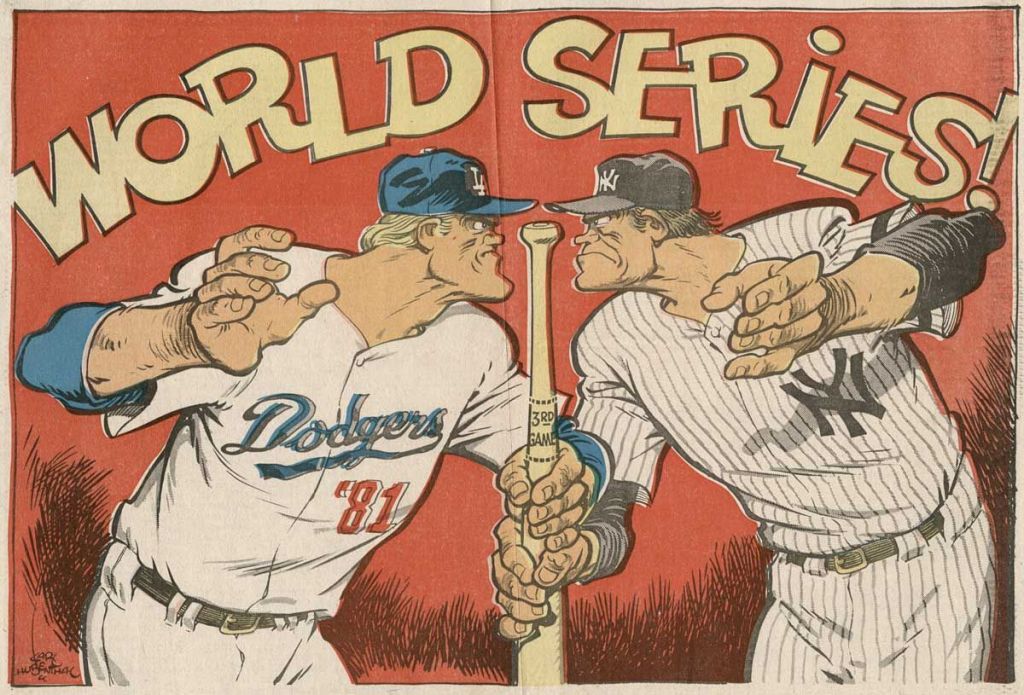

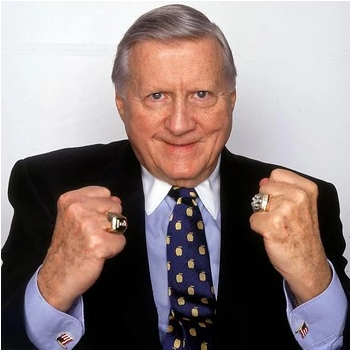

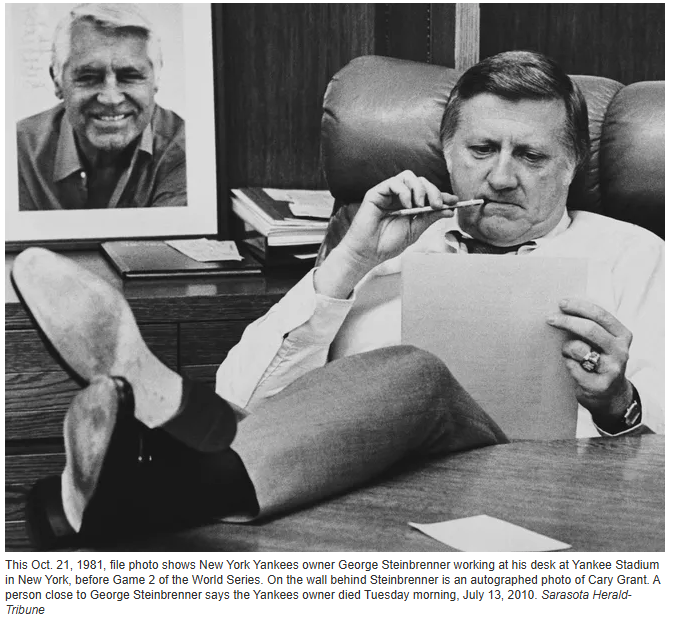

George Steinbrenner got into a scuffle with the two Dodgers fans in an elevator at the Hyatt Wilshire Hotel in Los Angeles during the 1981 World Series.

Broke his land. Left the two lads cowering and running away. The fans were razzing him because his Yankees, after winning the first two games of the series in New York, were just swept in three games at Dodger Stadium and heading back to the Bronx wounded.

At least that’s the story the late Yankees owner took to his grave.

So …….. Did it happen?

United Press International, a major wire service at the time, wrote it up, crediting a source for its information. (The source: Steinbrenner). The New York Times seemed a bit more skeptical when it reported that “cheerful” Steinbrenner “summoned a group of reporters to his hotel suite at 11:30 last night to explain what had happened and display his wounds — a bump on the head, a swollen lip, a right hand with a bandage over his cuts and an apparently broken left hand with a bandage over the cast.”

David Kindred in the Washington Post put it this way:

The news George Steinbrenner makes is only part of the fun. We get more laughs trying to figure out what really happened.

Hotel security and L.A. police said Steinbrenner made no report of the incident.

Maybe it happened exactly the way Steinbrenner told it.

Reporters went to other Yankee pugilists for comment yesterday. At the L.A. airport, Reggie Jackson said, “I don’t know anything about it. Don’t ask me.” Relief pitcher Rich Gossage, who sprained his thumb in a clubhouse scuffle two seasons ago, laughed and said of Steinbrenner’s broken hand in its cast, “George wouldn’t punch anyone . . . He must have caught it in an elevator.”

In 2004, the New York Times’ Murray Chass revisited it. Again with a lack of conviction, since there were no convictions:

Joe Louis? Rocky Marciano? Sugar Ray Robinson? They apparently had nothing on Steinbrenner.

Steinbrenner, 51 years old at the time, said that in rapid succession he threw three punches — two rights and a left. Down went the first miscreant; down went the second.

Muhammad Ali? He might have stung like a bee, but Steinbrenner said he swung a sledgehammer.

”I clocked them,” Steinbrenner told reporters just before midnight in a news conference he called in his hotel suite. ”There are two guys in this town looking for their teeth and two guys who will probably sue me.”

Bizarre as it might have been, the story of the fight remains part of the lore of the Steinbrenner years. What other owner could have engaged in such an episode? Peter O’Malley? Carl Pohlad? Bud Selig? Marge Schott?

No, this is one of those things that makes Steinbrenner special. He won’t be around forever, but this tale will be.

Steinbrenner died in 2010 at age 80. Still the undisputed champion of owner brawls during a World Series.

Crack open this collection of 18 stories that happened during baseball’s “glory” time of October, this would have been the time for a new revelation: The guys who did it have fessed up. The hotel security camera footage has been revealed. Hal Steinbrenner unsealed his father’s confessions that it was all a ruse — there was an elevator malfunction and he tried to punch himself out of the roof because he was claustrophobic but it just caused more damage.

Alas, this story isn’t included. A swing-and-a-missed opportunity.

But it’s not like it’s going away. During the 2023 World Series, a site called the BroBible in a piece by someone named deputy editor Connor Toole retooled it.

“If the entire thing was, in fact, an elaborate ruse, it didn’t have the intended effect, as the Yankees ended up losing the World Series by falling to the Dodgers in Game 6.”

The lede was buried. Down went Steinbrenner. Down went the Yankees. The Boss’ split lip didn’t help resolve this Split Season mess.

Nevertheless, there was some other things worth revisiting.

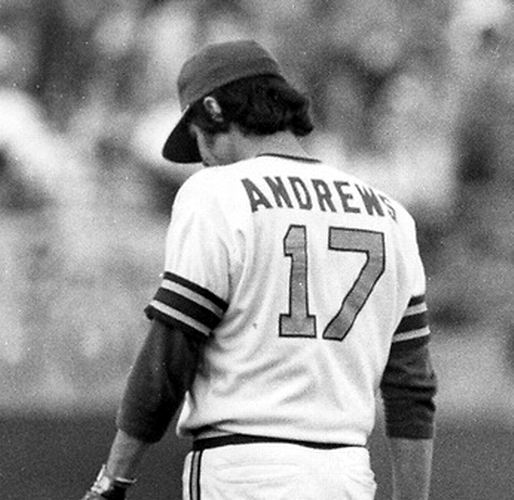

Mike Andrews, Oakland A’s reserve second baseman, 1973 World Series, when owner Charlie Finley tried to get his medical team to declare him unfit for duty (after he made a couple of costly errors during an extra-inning lost), and the team threatened to boycott the rest of the series against the Mets.

Rube Marquard, the Brooklyn Robins pitcher busted for trying to scalp tickets before Game 4 of the 1920 World Series. Then his wife divorced him. He still made it into Baseball’s Hall of Fame with a record of 201-177 and 3.08 ERA as “probably the worst starting pitcher” ever allowed into Cooperstown according to Bill James, most of his fame based on three very good years for the New York Giants from 1911 to ’13, and a 19-win season for Brooklyn.

Tom Browning, who disappeared during Game 2 of the 1990 World Series when Cincinnati Reds manager Lou Pinella went looking for him as a game was going into extra innings. Browning’s wife went into labor. He left the park without telling anyone. The team sent word through the TV broadcast that he was needed back as the game was going long.

Bill Bevens, the New York Yankees pitcher who was one out from a no-hitter in Game 4 of the 1947 World Series against the Brooklyn Dodgers, lost it, pitched 2 2/3 more inning of relief in Game 7 and never pitched another game again because of a bad arm.

Brian Doyle, not the Yankees’ 1978 World Series MVP in their win over the Dodgers, but he could have been based on his two three-hit games in Games 5 and 6, finishing the series with a .438 average, and never hit .200 in a season after that.

And on, and on …

How it goes in the scorebook

Lots of great topic ideas. Not a lot of fulfilling execution.Only seven people were interviewed for this … and a couple, it seems, just to get blurbs.

Where is an update on Mike Andrews? Or Doyle …. Or …. (Andrews spoke to the New York Times in 2010 by the way).

There’s also a lot of extraneous background material on the Series itself before we get to the prime suspect of the chapter. Some of it is great to know. But too many details muck things up. Publishers’ Weekly backs this up: “Though the anecdotes occasionally amuse, they’re bogged down by a surfeit of background. Only die-hard baseball fans need apply.”

Circle back in October and maybe this will feel more relevant.

For now, kinda trivial. Unless you got new info on Steinbrenner and the two dudes from L.A. …