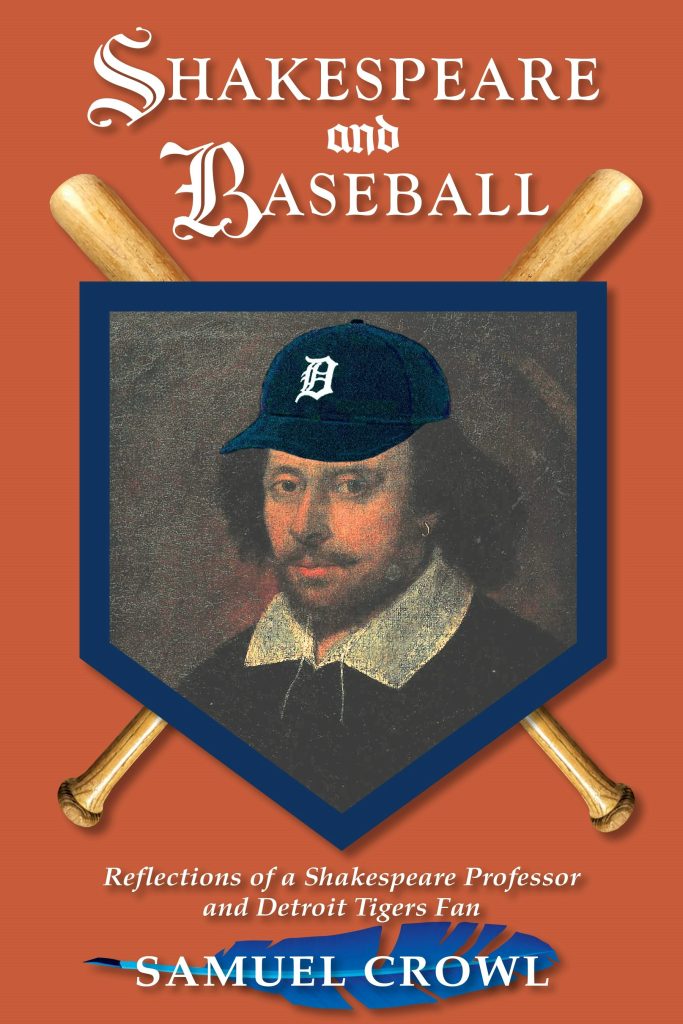

“Shakespeare and Baseball: Reflections of a

Shakespeare Professor and Detroit Tigers Fan”

The author:

Samuel Crowl

The publishing info:

Ohio U Press / 1804 Books

Pages; $21.95

Released March 19, 2024

The links:

The publishers website

At Bookshop.org

At Powells.com

At Vromans.com

At TheLastBookStoreLA

At Skylight Books

At {pages a bookstore}

At BarnesAndNoble.com; at Amazon.com

The review in 90 feet or less

The Major League Baseball odyssey of pitcher Daniel Bard continues to play out like a Shakespeare soliloquy.

Bard’s first act, five seasons from 2009 to 2013 with Boston, and his second act, five more seasons from ’20 to this calendar year with Colorado, had an eight-year intermission.

Can he explain this 2,600-plus day gap in his resume.

Yup. He had the yips.

In ’23, a season where he spent three stints on the injury list for the Rockies, he pitched a game against his former team at Fenway Park. And got the win. Ten years after he departed from the team under a storm cloud in his mind.

New Yorker magazine made note of this achievement, and explained his plight:

Everyone figured that Bard would become a star. Instead, he lost control of his pitches. He missed spots by inches, then by feet. The ball would leave his hand traveling 97 mph, then bounce in the dirt, or sail toward the backstop, or drill the batter’s shoulder. Each time, he had to get back on the rubber to throw another pitch, with no idea where it would go. He blew leads. He bruised batters. He stood on the lonely island of the mound, engulfed by jeers. He was sent to the minors, where he spent five years trying to relearn what had once felt automatic. Finally, in 2017, he quit.

There are other cases, in baseball history, of players who suddenly couldn’t pitch or throw. It’s an affliction so dreaded that players sometimes refer to it as a disease or a monster — if they’re willing to talk about it at all. But Bard came to realize the necessity of facing it. Two years after retiring, he returned to baseball and became one of the most dominant relievers in the game. It was a remarkable and unprecedented comeback. It wouldn’t be his last.

Bard told the Boston Herald: “It’s wild, man. It’s definitely a little bit surreal, in a good way. I always wanted to come take my kids to a game here when they got a little older, I didn’t think I’d be playing in it, I thought I’d just be taking them as a fan.”

Wild indeed.

Bard’s last appearance in Boston: April 27, 2013. Two walks and allowing a run without recording an out in a 8-4 loss to Houston. He was sent to the minor leagues, released, and it looked like it was done.

But after a break, Bard proclaimed in 2018 he would try again. He signed a minor-league deal with Colorado in 2020. He made the opening day roster in the pandemic-shortened season. By ’22, he was one of the league’s top closers with 34 saves and a 1.79 ERA.

“It’s crazy, it’s wild that I’m here,” he said again.

In ’23, he started the season on the 15-day injured list, missing three weeks. He made the courageous declaration that it had to do with anxiety issues. It made sense. While pitching for Team USA in the 2023 World Baseball Classic, during a March 18 game against Venezuela, Bard faced four batters. All reached base, including Jose Altuve, who Bard hit with a pitch that left the Astros star with a broken thumb, needing surgery and forcing the Astros’ All Star him to miss the season’s first 43 games.

In the middle of ’23, the Denver Post’s Patrick Saunders wrote a piece: “A salute to Daniel Bard’s career and forthright battle vs. anxiety.” It started: “Daniel Bard is a pitcher, and a man, worth celebrating.”

By the end of ’23, Bard had two more IL stints, with right forearm fatigue, and finally at the end with a right forearm flexor strain. But as the 38-year-old enters the final year of a two-year, $19 million contract, he is back on the 60-day IL to start the 2024 season. In spring training, he tore the meniscus in his left knee while playing catch. Then it was discovered he needs surgery to repair the flexor tendon in his right elbow and will not pitch again in ’24.

“My tendency is to rush things back. If I could be pitching at even 80 percent. I’m going to find a way to be out there,” Bard told MLB.com last February from his home in Greenville, S.C. “This forces me to pull the reins back and just take things a little slower. It’ll be a good thing in the end.”

The Bard of Avon, William Shakespeare, wrote in Act II of his play “As You Like It”:

“Sweet are the uses of adversity, which, like the toad, ugly and venomous, wears yet a precious jewel in his head; and this our life, exempt from public haunt, finds tongues in trees, books in the running brooks, sermons in stones, and good in every thing.”

It’s been noted that in Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet,” two star-crossed lovers are faced with great adversity, hiding their romance from their feuding families. As we recall from our high school honors English class, it didn’t end well.

As for Shakespeare lines above, however, there are many interpretations of what that actually means. One writer spelled out what it has meant to her:

Adversity builds character: Going through tough times can teach us important lessons about resilience, determination, and perseverance. When we overcome challenges, we become stronger and more capable of facing future obstacles.

Adversity fosters creativity: When we’re forced to think outside the box in order to solve problems, we can come up with innovative solutions that we might not have otherwise considered.

Adversity promotes growth: Facing adversity can force us to confront our weaknesses and limitations, and can push us to improve ourselves in order to meet the challenges ahead.

We’re almost positive the Bard of Colorado, Daniel, could relate to this. Just don’t go Willy Loman on us at this point of the journey.

If we check our Spark Notes, it reads: Between 1595 and 1600 Shakespeare faced a series of adversities that no doubt affected him profoundly, even as he continued to produce first-rate plays at a blistering pace. Many of the adversities that arose during this time related to the precariousness of the theater. In 1595 the Lord Chamberlain’s Men were preparing to move into a new theater in the Blackfriars district of London, when the Countess Elizabeth intervened. … Another patron adopted the players, but also because the company underwent a restructuring that involved the actors themselves, Shakespeare included, taking a financial stake in the company. The construction of the famous Globe Theater in 1599 ensured the company’s survival into the next century. Perhaps the greatest adversity Shakespeare faced during this period was the death of his only son, Hamnet (a twin, with a sister Judith). Scholars speculate that though Shakespeare no doubt grieved Hamnet’s death at the time, this grief would not find expression in his writing until around 1600, when he wrote the play that bears his dead son’s name—“Hamnet” and “Hamlet” were synonymous at the time. If this is true, then Shakespeare’s expression of grief takes an unexpected form in the play. Instead of the central grief being that of a beloved son’s death, the play centers on the murder of a cherished father.

If you’ve made this far, how about a reminder about This Date in Baseball: April 23, 2022: Detroit’s future Hall of Famer Miguel Cabrera collected his 3,000th hit.

And, This Date in Global History: April 23, 1564: William Shakespeare is born, 460 years ago, in Stratford-upon-Avon, England. Although his official date of birth is unknown, this is when it is observed, since records show he was baptized three days later. Where exactly was he born? Depends on who you ask.

And, April 23, 1616, at age 52, William Shakespeare died, in Stratford-upon-Avon. His final resting place is in that city’s Church of the Holy Trinity. His headstone reads:

Good friend, for Jesus’ sake forbear,

To dig the dust enclosed here.

Blessed be the man that spares these stones,

And cursed be he that moves my bones.

Cabrera was 39 when he reached his 3,000th hit. It is said Shakespeare’s number of dramatic works were about 39. Scholars debate that, as well as which ones were comedies, tragedies or dramas. That can add to the drama.

Samuel Crowl, an international Shakespeare scholar and fan of the Detroit Tigers, loves to make delicious connections between his two passions in this hymnal of a book project, a memoir that allows us to stretch our creative minds and find another way baseball permeates our belief that the play’s the thing we all embrace.

Crowl, awarded an Honorary Doctor of Humane Letters at Ohio University in 2015 and was its commencement speaker, writes he made his first Bard-Tiger connection in the summer of 1950. As a 10-year-old, he admired Detroit pitcher Hal Newhouser as he outlasted the Chicago White Sox in the first game Crowl attended. “Prince Hal,” as Newhouser was known, was the name of Shakespeare character given to Henry V of England in two plays, “Henry IV, Part 1” and “Henry IV, Part 2,” a term Falstaff uses to describe the lad who would ascend to the throne.

The first Shakespeare play Crowl was at age 12 — Alec Guinness as Richard III in nearby Ontario, Canada. His parents took him on repeated summer trips to Stratford, “where Shakespeare established his power on my imagination.”

Once you sense the overlap from Alec Guinness to Al Kaline, from Ian McKellen to Kirk Gibson, or Simon Russell Beale to Sparky Anderson, you can’t help yourself, finding some comfort in watching the Tigers’ ups and downs and going sideways over the years as the city of Detroit continues to have its own social growing pains, and Crowl views it from his residence in Bloomington, Indiana and lately from Athens, Ohio.

The third element of Crowl’s project is also how he used the first two elements to connect to his family, especially when writing letters to his children to update them on the Tigers’ progress as they were away at school. He could find himself at a Shakespeare Association of America convention with access to Fenway Park where his Tigers happened to be playing the Red Sox on Opening Day 1988 — Kirk Gibson had just departed to the Dodgers, and now it’s Alan Trammell, batting cleanup as the shortstop, hitting a two-run homer in the 10th inning to win the game for Jack Morris, triumphing over Roger Clemens. Yes, on Opening Day, both Morris (nine Ks, three earned runs) and Clemens (11 Ks, three earned runs) went the first nine innings. Morris got the win as he was still the pitcher of record. Red Sox reliever Lee Smith took the loss. And that ’88 season ended with the Red Sox winning the AL East by one game over the Tigers.

“This little book has three bases and a longing for home,” Crowl writes at the start.

Besides, as Crowl continues, “baseball is the writer’s game. Poets, novelists, essayists, biographers, historians and even Shakespeareans have found the game irresistible. Writers love the pace and grace of the game and the way it invites history to seep into the watching of any individual encounter. What other game has its own national anthem (played not at the beginning, but as the game reaches its climax), an Iowa field of dreams, and mock-epic poem?”

You can’t help but keep going stanza after stanza.

How it goes in the scorebook

Poetic in that we rose today, finished reading this, produced the review, and felt as if we actually seized the day, as they say. Mostly, seized the date — Four-twenty-three-twenty four could be just the right combination for a comedy of eras.

You can look it up: More to ponder

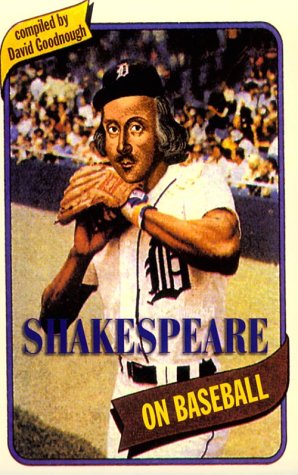

== There is also a Tigers-Shakespeare connection in this self-published tome, from almost 25 years ago: “Shakespeare on Baseball: Such Time-Beguiling Sport” by David Goodnough.

== A 1990 Letter to the Editor in the New York Times under the headline “What Shakespeare Knew About Baseball” reads:

To the Editor:

It’s time to settle once and for all the debate over the first references in print to the game of baseball. The earliest references to baseball occur in the plays of William Shakespeare and include the following:

“And so I shall catch the fly” (“Henry V,” Act V, scene ii).

“I’ll catch it ere it come to ground” (“Macbeth,” III, v).

“A hit, a very palpable hit!” (“Hamlet,” V, ii).

“You may go walk” (“Taming of the Shrew,” II, i).

“Strike!” (“Richard III,” I, iv).

“For this relief much thanks” (“Hamlet,” I, i).

“You have scarce time to steal” (“Henry VIII,” III, ii).

“O hateful error” (“Julius Caesar,” V, i).

“Run, run, O run!” (“King Lear,” V, iii).

“Fair is foul and foul is fair” (“Macbeth,” I, i).

“My arm is sore” (“Antony and Cleopatra,” II, v).

“I have no joy in this contract” (“Romeo and Juliet,” II, ii).

I trust that the question of who first wrote about baseball is now finally settled.

= Earl L. Dachslager, The Woodlands, Tex.

== And we part with this: