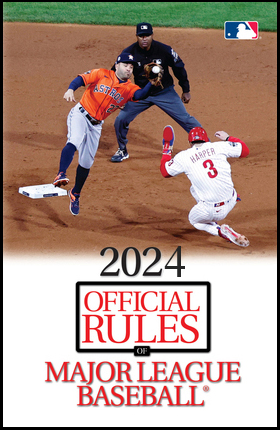

“Lion of the League: Bob Emslie and

the Evolution of the Baseball Umpire”

The author:

Larry R. Geralch

The publishing info:

University of Nebraska Press

432 pages; $39.95

Released May 1, 2024

The links:

The publishers website

at Bookshop.org

at Powells.com

at Vromans.com;

at {pages: a bookstore};

At BarnesAndNoble.com; at Amazon.com

The review in 90 feet or less

If Angel Hernandez is the only umpire you know by name currently working MLB games, heaven help us.

If he is showing some bedeviling trending on social media at any moment, be sure there’s hell to pay.

His most recent career arch has been, from every vantage point, detrimental for the game’s credibility. And it is amplified even more because of those in the sports wagering business fully engaged in the MLB’s revenue stream and demanding more accuracy in all outcomes. As a result, human error is no longer tolerated. Human incompetence and arrogance make it even more cringe-worthy.

Today’s MLB — following the lead of the NFL — has expanded its video replay system to get as many calls “right” as possible. It compromises the game’s ebb and flow, stopping the action as various moments of suspense to make fans and players await an outcome that, right or wrong, at least allows the game to continue. Soon enough, the unrefinement of robotic umpires, currently testing out in the minor leagues, are in the on-deck circle for MLB usage.

If the future of robo-calls ever come to pass in the MLB, Angel Hernandez will likely be blamed for it.

Since he came into the National League umpire ranks in 1991 and then was part of the merger of the league’s crews in 2000, Hernandez has now got his Wikipedia page that clearly has a red-flag warning: “Hernandez has been involved in several controversial incidents and has been widely criticized by players, coaches, and fans throughout his career.”

The 63-year-old, by the way, has not worked a World Series since 2002, or a championship series since 2005. It caused him to file a federal discrimination lawsuit in 2017 claiming he’s been wronged. The court action failed. Yet, he keeps working. Because he’s such a nice guy and has a strong union behind him? That seems to be the case.

MLB doesn’t seem to want to hold him accountable to expectations of performing just credible work to maintain the game’s stated rules.

His work on the basepaths are one thing. He’s had plenty of those safe-out calls overturned by replay. Yet some of his balls-and-strike calls behind the plate come out above average. Not always, but when he does blow it, he does it spectacularly. To be fair, he did a pretty fair job behind the plate during the Dodgers-Mets game on Sunday at Dodger Stadium. A 95 percent overall accuracy and 95 percent overall consistency in a 10-0 game is considered nice and clean:

However, the game before that one looked more like a Rorschach test with an 85 percent called-strike accuracy — 11 of 72 called strikes were actually balls.

And then there’s this chart 2023, said to be the lowest single-game accuracy rate any MLB umpire over the previous five years. Almost one of every three called strikes was actually a ball. In a 2-0 game, that’s pretty huge:

When Hunter Wendelstedt was behind the plate for an April 22 game between the New York Yankees and Oakland Athletics, and ended up ejecting Yankees manager Aaron Boone five pitches in, it was the start of a long day for the ump. His called strike accuracy was only 68 percent.

Compare that the 100 percent strike called accuracy that umpire John Tumpane had during the Dodgers-Blue Jays game in Toronto on April 27.

All in all, at least they aren’t going to be remembered like Rob Drake, who in 2019 once tweeted out a threat of “a cival war” if Donald Trump was impeached as president. And somehow kept his job.

How much more should umps be held accountable for their own actions?

Which leads us now to the overall question for an arbitrator:

When did umpires come about, why were they actually needed, how were they trained, what is their evolution and … is it still the best-case scenario if fans never get to know their names?

In this moment of time, veteran umpire researcher and University of Utah history professor Larry Gerlach has called our attention to a gem of a project.

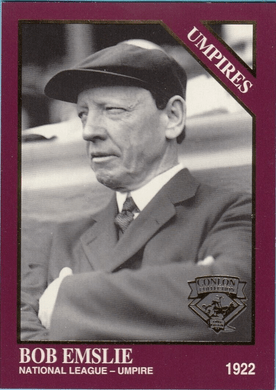

In his introduction, the author of the 1980 book, “The Men in Blue: Conversations with Umpires” (originally published by Viking Press, with a 1994 version updated by University of Nebraska Press — and Hernandez is not included in the new material) dials it back to the life and times of someone once referred to as “Blind Bob” Emslie.

It was also a book Gerlach said he didn’t intend to write. He knew nothing about Emslie until March 2019 when heard about him in a baseball history symposium. He decided “an Emslie biography would not only address a void in baseball literature but also amplify baseball’s pursuit to legitimize the modern game and track the umpiring’s transition from “a contentious temporary job to an esteemed professional career.”

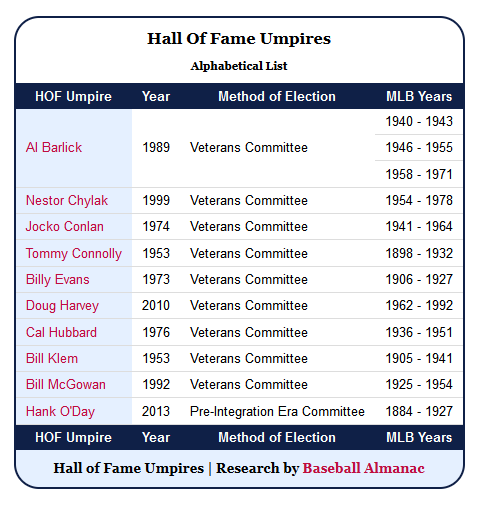

Because of Gerlach extensive research — in today’s world, that means having access to many more pieces of game stories and box scores than in the past — it’s not out of the question that Emslie will end up on some future Baseball Hall of Fame Veterans Committee ballots, joining the lonesome 10 already inducted over the last 80-plus years for their outstanding work.

Before setting records for longevity as an umpire, Emslie, born in 1859, was a darn-good player — Canadian born, left-handed pitcher for three seasons for the Baltimore Orioles of the American Association (44-40, 3.08 ERA, 82 complete games in 86 starts). His most amazing stats: Posting a 32-17 record in ’84 with a 2.74 ERA in 50 starts, and 50 complete games, logging 455 1/3 innings. He pitched four more games for the AA’s Philadelphia Athletics before he was done with a sore arm in 1885.

Three years later, he entered the umpire profession, somewhat by accident because one was needed at a game he was attending. First, in the minor leagues, then in the American Association by 1890, then with the National League starting in 1891.

Players could get on him for many reasons but one nickname that stuck was “Wig” because of a receding hairline (he actually wore a toupee during his playing career).

His most famous game was during the 1908 NL pennant race — Sept. 23, ending on the “Merkle’s Boner” play — a force out at second base when Fred Merkle, the New York Giants runner, started from first and pulled up short after the game-winning run scored ahead of him. Chicago Cubs second baseman Johnny Evers spotted it, tagged second, and appealed to Emslie. He said he didn’t see it because he had ducked to get out of the way of the line-drive hit. Emslie appealed to home plate umpire (and future Hall of Famer) Hank O’Day, who called Merkle out, the game was declared a tie.

By the time Emslie retired at age 65 in 1924, he set records (later passed by Joe West) for most seasons (35), most games (4,231). He called four no-hitters from 1983 to 1907. He then became an NL umpire chief to cultivate the new generation of arbiters. He (and Bill Klem) have the record for fastest game in history — 51 minutes on Sept. 28, 1919). He never umpired a World Series.

His career, as Gerlach points out, also came “during a time of profound technology, industrial, commercial, transportative and demographic change as well as two world wars, a devastating viral pandemic, and the Great Depression.”

He made it into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame (1986). There is a baseball field in St. Thomas, Ontario, Canada named in his honor.

His April 27, 1943 obit in the New York Times called him the “dean of umpires” who had a trapshooting title and a noted curve ball.

It ended with the paragraph: “Reporters found it difficult to interview Emslie, but on one of those rare occasions when he talked for publication he called Christy Mathewson the greatest pitcher of all time and Hans (Honus) Wagner the greatest all-around player.”

And he stuck to that to the end.

How it goes in the scorebook

This book rules.

Umps may feel they have thankless jobs. It may have been a somewhat thankless task that Gerlach proceed with this project.

But the result is a clear documentation that gives readers and fans of the game better context not just of the position’s evolution, but of its importance, and how someone like Emslie could make a living out of it and keep a profile under the radar from most media reporting.

This book may be much thicker than a standard MLB rule book. But it’s justified. If it was just a bio on Emslie, it would have been enough. But context and history and all sorts of things were needed research by Gerlach to achieve this.

You can look it up: More to ponder:

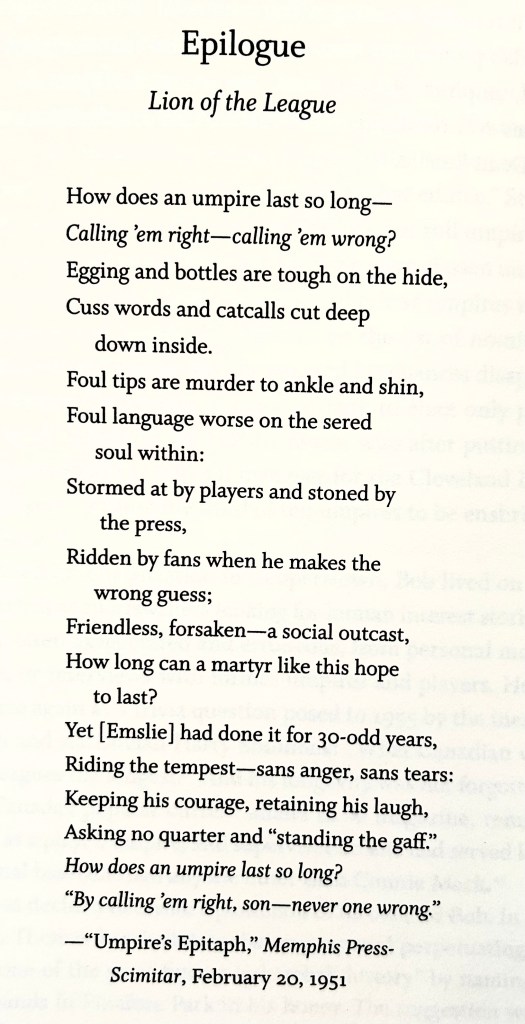

== How the book got its title: From the first page of Gerlach’s epitaph:

== The 10 umpires currently in Baseball’s Hall of Fame:

More who could be considered: Joe West, Gerry Davis, Jim Evans, Cy Rigler, Tommy Connolly, Harry Wendelstedt, Tim McClelland … Jim Joyce? And, yes, Emslie.

== Bob Emslie’s biography for the Society for American Baseball Research includes the opening line written by David Cicotello calling him “the least-known famous umpire in baseball history” (words repeated by Gerlach in the preface) and his 54 years involved in the pro game — six as a player and 49 as an umpire and 11 as a supervisor — as having a career that is “by any standard one of the most extraordinary in baseball history.” (And Emslie is a Scottish surname meaning “woodland clearing.”)

== Several umpires have done their own books over the years. In 2014, two came out — “They Call Me God: The Best Umpire who Ever Lived” by Doug Harvey, and “Called Out but Safe: A Baseball Umpire’s Journey” by Al Clark (the first Jewish umpire in AL history). The 1982 book by Ron Luciano, “The Umpire Strikes Back,” which he unleashed so many funny stories it led to a TV gig with NBC Sports on MLB games as well as three sequels (“Strike Two” in ’84, “The Fall of the Roman Umpire” in ’86 and “Remembrance of Swings Past” in ’88). Those all came after the 1998 book: “You’re Out and You’re Ugly Too! Confessions of an Umpire With an Attitude” by Durwood Merrill. That may have opened the door on the jovial demeanor of umps we weren’t always allowed to see, some of which was also in the book, “Three and Two! The Autobiography of Tom Gorman, The Great Major League Umpire” in 1979 (as told to Jerome Holtzman). Others are by Durwood Merrill, Eric Gregg, Dave Phillips and even Pam Postema. Dale Scott’s book in 2022 also focused on his coming out, after Dave Pallone did “Behind the Mask: My Double Life in Baseball,” which came out first in 1990, updated in 2002.

Others: Bill Nowin’s 2020 book, “Working A ‘Perfect Game’: Conversations with Umpires,” which we reviewed. Also “As They See ‘Em: A Fan’s Travels in the Land of Umpires” by New York Times writer Bruce Weber in 2009.

== Emslie was an umpire long before at a time when stories like this would come up in the newspaper:

== Nobody loves the ump? Surely, many do. Without them, there would be even more chaos. But you wouldn’t have this routine either:

1 thought on “Day 22 of 2024 baseball book reviews: Maybe if justice is blind, “Blind Bob” Emslie can justify a new viewpoint”