“Team of Destiny Walter Johnson, Clark Griffith, Bucky Harris and the 1924 Washington Senators”

The author:

Gary Sarnoff

The publishing info:

Rowman and Littlefield;

250 pages; $38

Released Feb. 10, 2024

The links:

The publishers website; at Bookshop.org; at Powells.com; at Vromans.com; at {pages a bookstore}; at BarnesAndNoble.com; at Amazon.com

The review in 90 feet or less

After the 2019 Washington Nationals stupidly walked into a championship, a quick-print book about that team came out by the Washington Post’s Jesse Dougherty called “Buzz Saw: The Improbable Story of How the Washington Nationals Won the World Series.”

That post season journey included witnessing the Nats dissemble the 106-win Dodgers, going the distance in a best-of-five National League Divisional Series. The last win was executed at Dodger Stadium. There was heck to pay.

That NL East wild-card team had the “Baby Shark” power. And Anthony Rendon’s idiotic stats (34 HRs, 126 RBIs, 117 runs, .319 average). And rookie Juan Soto’s muscle. And Trea Turner’s speed. And veteran Howie Kendrick’s grand-slam gumption. And veteran Kurt Suzkuki’s intelligence. And the arms of Stephen Stasburg and Max Scherzer and do-nothing Sean Doolittle. And a year removed from Bryce Harper.

“You have a great year, and you can run into a buzz saw,” Strasburg told Dougherty after the team advanced to the World Series. “Maybe this year we’re the buzz saw.”

These weren’t your recycled Montreal Expo who started 19-31 and ended up with the District’s first title in 95 years. We enjoyed the book as something that needed to be reassembled for our disbelief.

That book also begat “You Gotta Have Heart: Washington Baseball from Walter Johnson to the 2019 World Series Champion,” by Frederic J. Frommer, reminding those who are confused about the history of the city’s major league baseball just what has and hasn’t happened. And could have happened.

Because, in a way, even if we watch today’s Washington Nationals play at the Dodger Stadium, we’re still a bit history challenged.

At our last count, 17 major professional baseball franchises have called Washington D.C. their home. Many shared the same nickname. Or switched midway.

The place better known for housing the Bill of Rights may have had the right idea, but often a wrong outcome.

Let’s work our way back in time:

Current day:

= Washington Nationals: A National League team since 2005, with Montreal’s Expos having its birthrights as an expansion team in 1969. The franchise was absorbed by the MLB so it wouldn’t disappear when Canadian ownership failed, and the team was re-imagined in the District’s RFK Stadium. They moved into Nationals Park in 2008.

Recent previous incarnations:

= Washington Senators: A founding member of the American League created in 1901. However, from 1905 to 1955, their official nickname was the Nationals. It changed back to the Senators after original owner Clark Griffith died following his 35-year run. They also had been referred to as the Griffs, after Griffith, during his managerial days from 1912 to 1920. Moved to Minnesota to become the Twins in 1960. Won the 1987 and 1991 World Series. As well as 1924 (where this book is laser focused).

= Washington Senators: An American League expansion team created in 1961 when the city’s previous team vacated. Moved to Texas to become the Rangers after the 1971 season. Won the 2023 World Series.

A very long, confusing time ago:

= The Washington Olympics: A member of the National Association from 1871 to 1872.

= The Washington Nationals: A member of the National Association in 1872.

= The Washington Blue Legs: A member of the National Association in 1873.

= The Washington Nationals: A member of the National Association, again, in 1875.

= The Washington Nationals: A member of the Union Association in 1884.

= The Washington Statesmen: A member of the American Association in 1884.

= The Washington Nationals: A member of the National League from 1886 to 1889.

= The Washington Statesmen: A member of the American Association in 1891.

= The Washington Senators: A member of the National League from 1891 to 1899.

= The Washington Senators: A member of the United States Baseball League in 1912, as the league folded one month into operation.

= The Washington Pilots: A member of the East/West League in 1932

= The Washington Potomacs: A member of the Eastern Colored League in 1924 to 1925.

= The Washington Black Senators: A member of the Negro National League in 1938.

= The Washington Homestead Grays: A Negro League team from 1930 to 1948 that also played in Homestead, Penn.

Then, the almost team:

= What if Tony Gwynn and the Washington Padres-turned-Stars were a team of destiny in the 1984 and 1998 World Series.

Considering that Gwynn’s Padres didn’t really fulfill any sort of destiny those two years — representing the city of San Diego, they lost the title to the Tigers in ’84 and the Yankees in ’98 — but there’s an onus becomes explaining how the Washington Padres almost came to happen.

In early 2024, Frommer wrote a piece for the Washington Post explaining all that — how 50 years ago, kids were opening up packs of Topps baseball cards and finding Dave Winfield, Nate Colbert and a bunch of others listed as playing for “Washington” and “Natl’ Lea.”

When Gary Sarnoff set upon focusing on the Washington Senators’ 1924 “Team of Destiny” march to the World Series title against the New York Giants, he had to a little housekeeping.

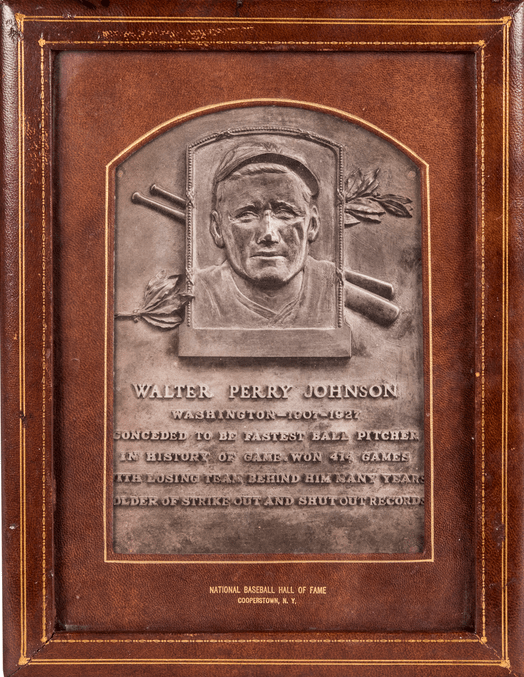

Starting with: If you think of the legendary Walter Johnson and his entire 21-year career spent entirely in Washington, it was actually officially playing for the Nationals instead of the Senators (see above) from 1907 to 1927, amassing 417 wins, 531 complete games, an MLB record 110 shutouts, and owning the all-time strikeout total of 3,509 after he retired at age 39 (and then became the Washington manager from 1929 to ’32).

In his Baseball Hall of Fame bio, it refers to him playing for the Senators. Never mentions the Nationals. And his plaque really could use a little more details with the stats “The Big Train” accumulated. Like, he had a 15.1 WAR in 1913 when he went 36-7 with a 1.14 ERA, greatest single-season total for any pitcher since 1900. And his 13.2 WAR the season before is second-best all time.

Yet, the classic vaudeville line continued to go “Washington: First in war, first in peace, last in the American League.”

The 1924 season was supposed to be it for former Fullerton product Johnson, among the league’s oldest players at 36, in his 18th season.

Instead, he won an AL-best 23 games, also leading the league with a 2.72 ERA, 38 games started, six shutouts and 158 strikeouts — the 12th and final time he was tops in that category in the league. He was also the AL’s MVP, decades before the Cy Young Award was considered.

The team also had 24-year-old future Hall of Fame outfielder Goose Goslin — a league-best 129 RBIs despite only 12 homers and a .344 batting average.

In charge was the game’s youngest manager, 27-year-old Bucky Harris, also the team’s second baseman. He replaced the fired Donie Bush after the ’23 season.

Harris also spent the winter hearing he was going to be traded to the New York Yankees. Instead, he led the AL with 46 sacrifice hits. He’d be Washington’s manager through 1928, come back from ’35 to ’42, leave again, and come back from ’50 to ’54, piling up 18 of his 29 seasons as a skipper there.

The team was 24-26 and sixth in the AL by mid-June before sweeping the New York Yankees at Yankee Stadium. Sarnoff explains how on Aug. 1, a motorist stopping for gas a mob of people rushing a newspaper delivery man. “What are they fighting for?” he asked. “It is the early edition of The Washington Post,” the station attendant explained. “From what I understand, it is all on account of the Griffs.”

Johnson was the main draw, the sentimental favorite of fans to see him finally win a title. He pitched in three games of the World Series against the New York Giants, including four scoreless innings of relief in Game 7 to get the win in a 12-inning classic.

“I didn’t have much confidence in myself,” Johnson, who squeezed in two more seasons after that only championship, would later recall, as Sanoff pulls a quote for page 185. “I was 36 years old, and that’s pretty far gone to be walking into the last game of the World Series — especially when you’ve lost two starts already. I remember thinking, ‘I’ll need the breaks,’ and if I didn’t actually pray, I sort of was thinking along those lines.”

He also told the news boys after the Game 7 win: “Tell everyone I’m tickled to death and everything along those lines you can think of. I’ll stand behind everything you say as I can’t express my feelings in words right now.”

Imagine that happening today.

How it goes in the scorebook

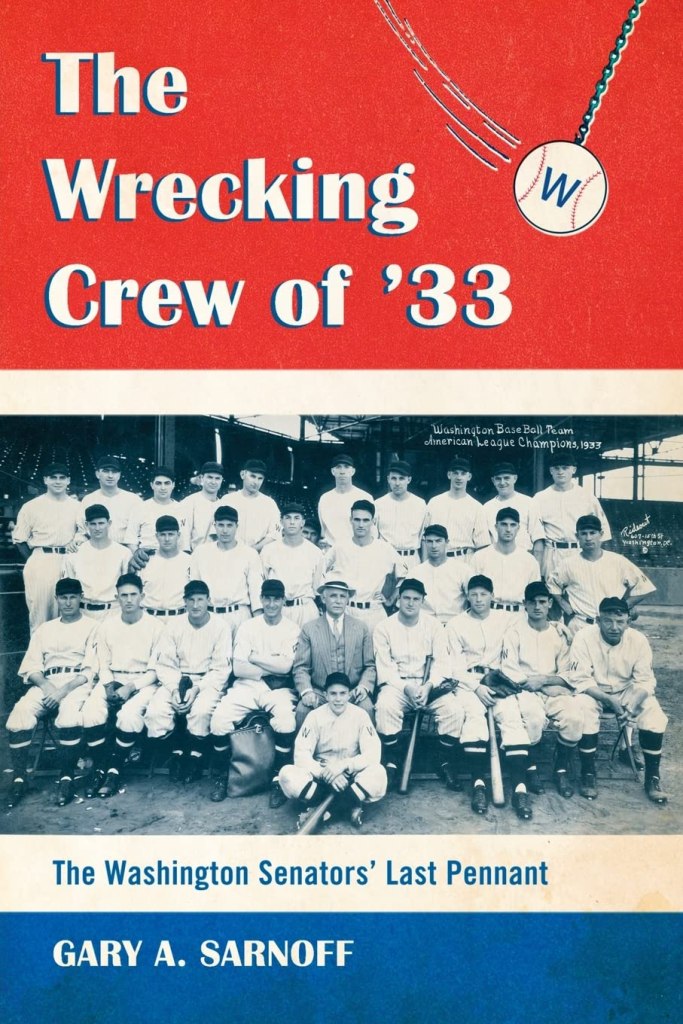

Pay attention to the details. It’s a century ago, and even the newspapers can be erroneous. Yet as Sarnoff takes the reader through the season, he doesn’t make it seem like it’ll end with something spectacular. Or improbable. Sarnoff, who already did the 2009 books “The Wrecking Crew of ’33: The Washington Senators’ Last American League Pennant,” and in 2014 “The First Yankees Dynasty: Babe Ruth, Miller Huggins and the Bronx Bombers of the ’20s,” is a SABR researcher who knows what he’s doing.

Later this year, the Washington Nationals will actually celebrate the 100th anniversary of this 1924 title, which really isn’t connected to their legacy. Might as well throw in a five-year party for its ’19 team too?

Heck, why not honor one Washington pro baseball team every day of the season. There’s enough to go around.

You can look it up: More to ponder

== Consider tracking down Hank Thomas’ 1995 biography of his grandfather titled “Walter Johnson: Baseball’s Big Train” (Farragut Publishing, 458 pages).