“The Tao of the Backup Catcher:

Playing Baseball for the Love of the Game”

The author:

Tim Brown

with Erik Kratz

The publishing info:

Twelve Books/Hachette

304 pages; $30

To be released July 11, 2023

The links:

The publishers website

The authors website

At Bookshop.org

At Powells.com

At Vromans.com

At TheLastBookStoreLA

At {Pages: A BookStore}

At Target

At BarnesAndNoble.com

At Amazon.com

The review in 90 feet or less

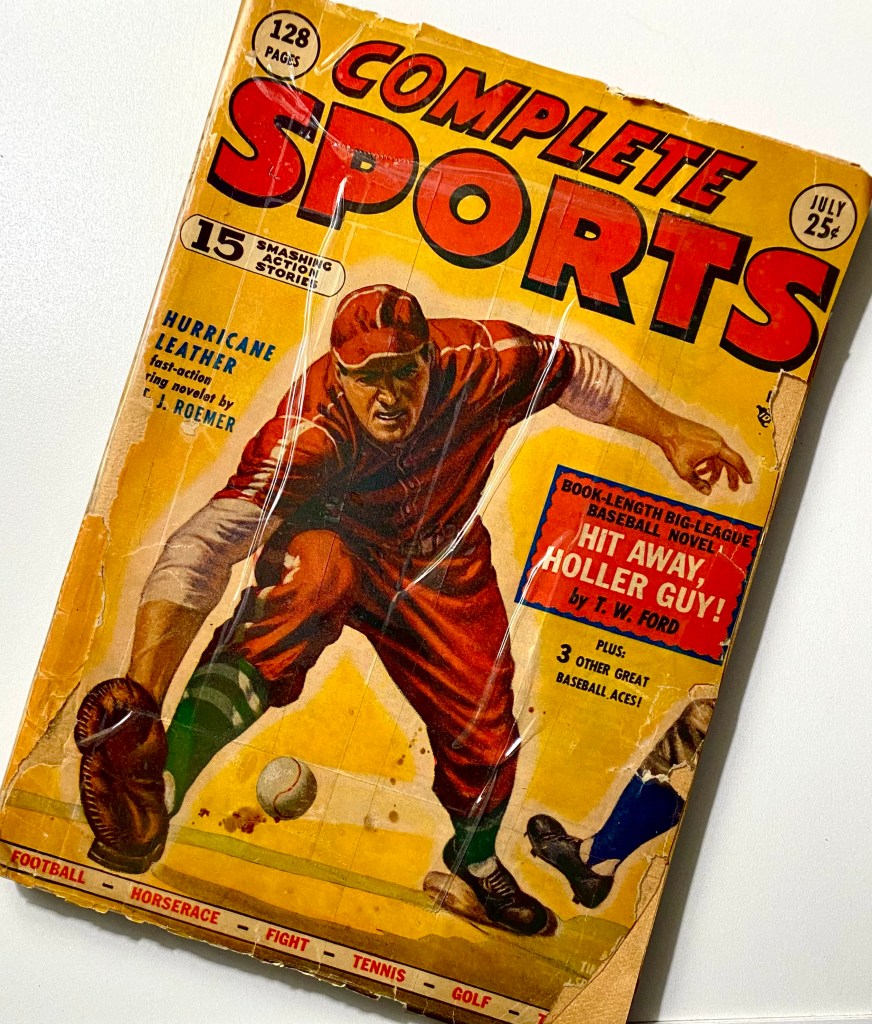

At our local favorite literary browsing spot, Dave’s Olde Book Shop in Redondo Beach, we found in the vintage/collectables section something called “Complete Sports” magazine. From July, 1948. Original price: 25 cents.

The cover lures us in to find a “book-length baseball novel” inside called “Hit Away Holler Guy!” by T.W. Ford. The artwork is fabulous from the brown musty pages of newsprint numbered 6 to 42. It becomes a full experiences for all the senses.

The premise, from the table of contents: “The new backstop was a real holler guy – but he would have to be the Angel Gabriel himself before he would wake up those eight dead men on the diamond!”

The magazine cover is all taped together. It is missing not only the back cover, but it ends with a torn page 129.

It is a piece of baseball history, held together by tape and staples and love.

Just like a real catcher could appreciate.

What does this tale published 75 years ago have to do with the essence of catchers having some secret powers? Can they really will people out of their graves back on the diamond? Is this some Field of Nightmares?

The demands on any Major League Baseball backup catcher might feel as if that includes being akin to a grave digger. Who really wants to do it? But, hey, we need it done, and you’re available. Isn’t this a path to dig one’s own hole into oblivion?

(First aside: We remember once finding out on the back of a Topps baseball card that the Pittsburgh Pirates’ Richie Hebner dug graves in the offseason. As a hobby? As we look for that card, check out the West Michigan White Caps minor league team (Hebner played for the Detroit Tigers for three seasons in the 1980s) as it once gave away a Hebner bobblehead about 10 years ago … it looks like this. The story goes that Hebner dug graves as part of his family business for more than 30 years. From his SABR.com bio: “He began earning $35 per grave in the off-season at home in Norwood, Massachusetts, working the nine Jewish cemeteries his father William supervised. Once, his dad criticized him for digging a grave too shallow. Hebner retorted, “I never saw one get up from it.”)

In scout parlance, the backup catcher is referenced as a “C2,” with a small No. 2. Like we’d see in a science class looking at a periodic table of elements.

Erik Kratz is the protagonist in this true-to-life assessment of his career as the “C2” no matter where he went – spending time on 14 MLB franchises during 19 seasons in organized pro baseball.

In every instance, Kratz becomes a vital part of the team’s chemistry and bonds with players, managers and bullpen throwers on a lot of important levels.

Kratz, who walked away after the 2020 season with the Yankees (his second tour), had one stop with the Angels, but don’t try to remember it – after the Houston Astros released him in May of 2016, the Angels picked him up and stored him away in Triple-A Salt Lake City, for 19 total at bats. Kratz may never know why they did that: To nurture an up-and-coming pitcher, perhaps.

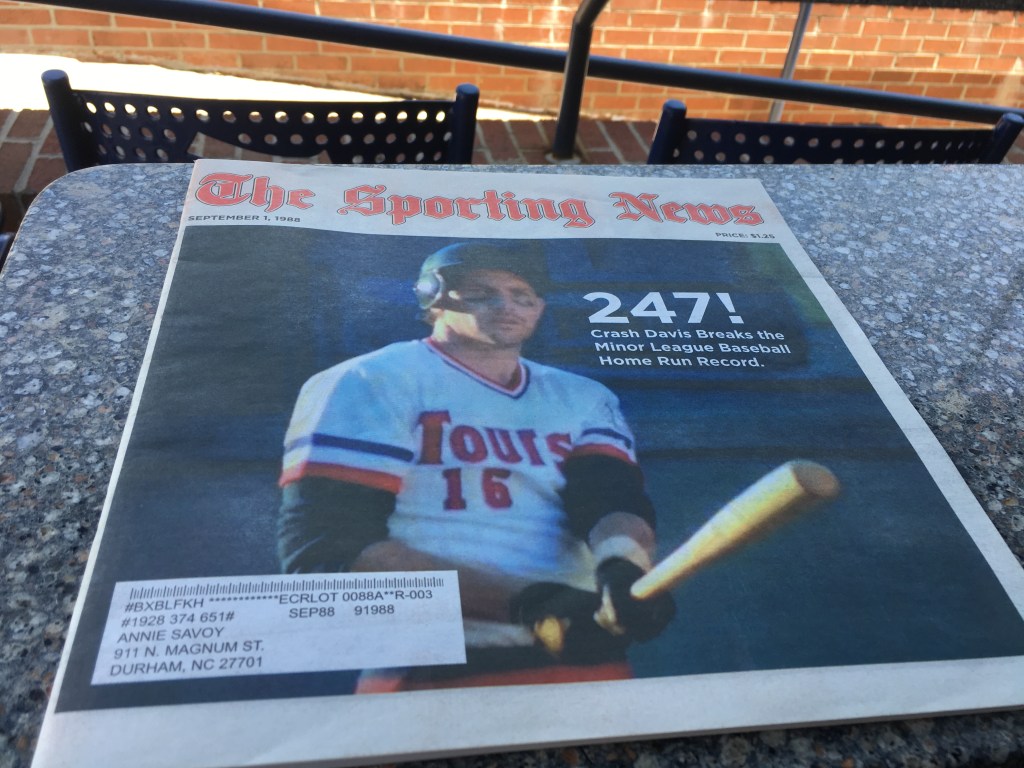

Yes, like Crash Davis.

Because, at the time, the Angels had banked on 33-year-old Geovany Soto, the former Cubs All-Star, as their main catcher, but he only lasted 26 games because of injury. They pulled in 25-year-old Carlos Perez for 87 games, and 26-year-old Jett Bandy for 70 games. Juan Graterol got in for nine games as a backup. But Kratz never got a shot.

These 74-88 Angels needed all the help they could get, if only to warm up another arm. They ended up using 30 pitchers that season, from Al Alburquerque to Tim Lincecum, Jered Weaver to Huston Street and even one game from Andrew Heaney. Tyler Skaggs even threw 10 games.

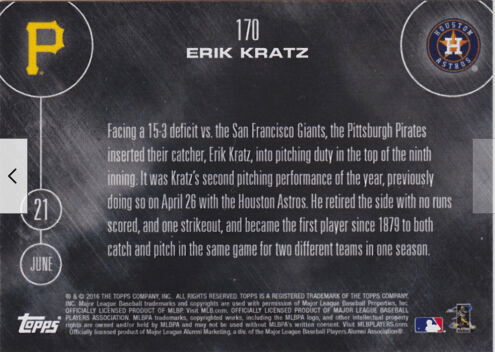

As it turned out, the Angels became a bridge in Kratz making some odd history that season.

The Angels traded him to Pittsburgh in mid-June, and after a couple days in Triple-A, he came up and did something that no one in the game had since 1879. Topps baseball cards even put out a special limited edition tribute to him.

On June 21, the Pirates had Kratz throw an inning at the end of a blowout loss to save their bullpen against the San Francisco Giants. Kratz ended up with one inning of scoreless relief. He even struck out Brandon Belt on a 52-mph knuckleball.

A few months earlier, the Houston Astros had treated him with the same urgent need. He surrendered two runs and three hits in one inning “of work,” as the cliché goes in the broadcasting booth.

That made Kratz the first player in 140-some years to both pitch and catch for two different teams in the same season.

Cool enough, Kratz would end up as the Milwaukee Brewers’ starting catcher in five of their seven-game NL Championship Series games against the Dodgers in 2018 — and also pitch in three games for the team that season, one inning each. He also made two final appearances for the Yankees, in 2020, at age 40.

His career pitching line: 7 games, 7 innings, 5.14 ERA, 32 batters faced, one walk, three Ks.

Through the quick prose quotes of Kratz, channeled through seasoned sportswriter and author Tim Brown, who already has two New York Times’ bestsellers on the market in helping tell the stories of former MLB pitcher Rick Ankiel and Jim Abbott, the story flows from chapter to chapter in a way that’s as much enlightening as it is entertaining. As Brown says in the intro: “They are not merely backup catchers, but front-line people.”

Kratz won’t be known as the guy who had 881 MLB at bats and only had a -0.1 WAR. He’ll now be known as someone who channeled his Souderton Mennonite Church believes into someone who knew what the job entailed, and did it, to support his wife and three kids. It’s where he learned his resilience, team-over-individual mentality, endurance, wisdom, patience, common decency, focus and following his heart.

In a story that ran in the Sporting News in September of 2020, just before he walked away, the reporters noted that Kratz had teared up when talking about how what he’s been as a mentor to Hispanic teammates with the New York Yankees. That’s just the kind of guy he is, and Brown also documents it. Kratz could also likely see the end of his pro career at that moment. It all caught up with him.

Brown manages to includes many recognizable names who’ve spent much of their career in that “C2” role – the Dodgers’ A.J. Ellis and Drew Butera (now an Angels’ bullpen coach), one-time Johnny Bench backup Bill Plummer and what it was like to spend his career behind a Hall of Famer never to get an inning in during all those playoff and championship runs, current Angels manager Phil Nevin (who converted to a backup catcher just to stay in the game at one point), plus Bobby Wilson, Jake Paul and even the poetry of Dodgers’ backup Austin Barnes stuffing the last ball used in the 2020 World Series into his back pocket for safe keeping after Julio Urias’ strike out. Rewards come far and few between, and the back up catcher must seize them when they happen.

There’s also a splendid discussion with former Angels manager Mike Scioscia (at one time, briefly the back up to Steve Yeager with the Dodgers) and the closed-door strategy sessions he put all Angels catchers through with his tutelage that only made them smarter and better at their position.

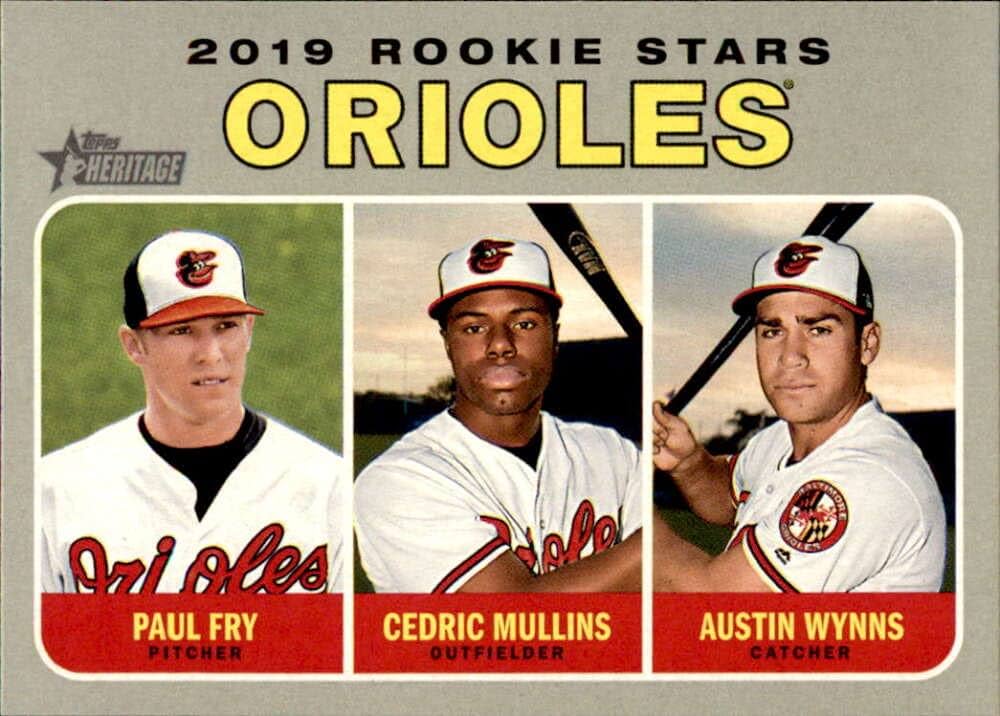

This books also makes us appreciate more what the Dodgers had for a brief time earlier this season in Austin Wynns.

The 32 year old was needed when Will Smith went out with a concussion. They designated him for assignment on May 1. Wynns got into six games, hit .154 but had an RBI double. The Dodgers were his third team in five seasons, including two stops in Baltimore and one in San Francisco. He has nine minor-league seasons logged already. Expect him to be on speed dial by any MLB team that finds itself up to their hips in alligators some day.

It can’t be an everyone Wynns-win situation for everyone. But it’s a necessary role.

They live the life, as Brown writes in the introduction, “with a grim sense of humor, a prorated paycheck and a handshake for understanding.” They are the “unlicensed therapists and hard-knock lifers whose careers wander off in unexpected directions, just like their fingers.”

“I always joke,” says Chris Gimenez, who had 10 seasons in the big leagues with six teams, “that backup catchers are three-quarters psychologist and one-quarter actual baseball player.”

Maybe someday Wynns gets into the MLB manager ranks, following Nevin, Bruce Bochy, Joe Madden, A.J. Hinch and David Ross. And he can write his own book.

It’s a smart move.

Author Q&A

We caught up with an email exchange with author Tim Brown, our former L.A. Daily News colleague who recently moved from many years in Southern California to South Carolina with his wife:

Q When in your sports writing career did you figure out that not only are the best baseball stories found in the corner of the locker room, but that the backup catchers were really the most front-line people?

A I think backup catchers are so good at reading people they recognized right away I was probably in need of some guidance. Major league clubhouses can be difficult, intimidating places, especially if you’re new to the job and aren’t finding a lot of friendly faces. So when somebody takes the time to help you through your dumb questions, educate you on the game, confide in you that he, too, sometimes feels unsure of himself, that resonates.

And, yes, maybe because those guys were in the literal corners of locker rooms, that there would be other players in the figurative corners, where big, strong athletes had all the doubts and vulnerabilities and life traumas of the cab driver who dropped me off in front of the stadium. I did a book with Jim Abbott. When he wasn’t pitching well and was feeling pressure from under performing, he would sit on the team bus, look out the window at the people in their cars and wonder what it would like to have a regular job. In those moments, he’d sometimes wish he were them. And he was a New York Yankee making millions of dollars.

These players, the famous ones whose names you know, they suffer the same insecurities the rest of us are hiding too. Or trying. As I thought about a book that might make the game feel real again, outside the analytical models, statistical tangles and revenue counts that now reach the tens of billions, I kept coming back to the backup catchers. Their honesty about themselves. Their fight to stay with it. The role they play in helping others live with those insecurities and turn them into competitive advantages. Hell, just a guy to share a beer with, who’s been there. Who lives with it every day.

Q How and when did you run into Erik Kratz for the first time, and how was he the best example of who to use as a narrative for this versus dozens of other candidates?

A In August 2018, I was doing a weekly podcast. These podcasts required guests. For many months, even years, I’d had as guests the likes of Albert Pujols, Mike Trout, Clayton Kershaw and Joey Votto. Superstars translate into ears, I figured. I was living in Los Angeles. That week the Milwaukee Brewers were in town. A week or so in advance, I was scanning the roster, seeking an interesting subject, saw Erik Kratz’s name and thought, “Well, this would be a cool change of pace.” He carried a great story of perseverance and, indeed, for the first time in his professional career – at 38 years old — had become a pseudo-No. 1 catcher. I’d heard of Erik, of course, but had never spoken with him. When I researched his story – son of a meat cutter, Division III college, late draft pick, married young, three kids, all those travels, all those transactions, and now being rewarded – I came to believe a podcast conversation with him could be interesting.

And he was delightful – self-deprecating, funny, intelligent, humble, family-oriented and quite serious about the game and his role in it.

We stayed in touch. We talked about a book about his life. I thought about a book about not one backup catcher, but all of them. The story would need a spine, one person who readers hopefully would relate to, because everyone wins a few, loses more, and can draw the energy to get up the next day and try it again. I spent a couple years talking to Erik and every backup catcher who would return my calls. It was a joy.

Q One of the things about how someone like Kratz will “take one for the team” is the fact that, for two different teams in the same season, he was not only their backup catcher but also pitched to eat up an inning at the end of a blowout. Is that something the average baseball fan may overlook – being that humble to make sure the game gets finished even if you didn’t make the mess you’re now cleaning up?

A Backup catchers want to play baseball. They spend so much time working at the game – for their benefit and others’ – in the 21 hours around those nine innings, I think they’d be delighted to take another one for the team. When you’re lugging around a career .209 batting average, a 5.14 ERA (Erik’s, across seven appearances) doesn’t scare you. And, another chance to have a laugh? Another chance to wear one for the good of the squad? Another chance to pick up a reliever you know is gassed and fighting a grumpy shoulder?

That’s the job.

On a 26-man roster, most of them analytically engineered to the last decimal point, there is one man who does not precisely fit the model. Because he’s the man who has to be the big brother, the father figure, the priest, the therapist and the drinking buddy, too. And the man who’s throwing 70-mph fastballs at big-league hitters in a nine-run deficit in a near-empty ballpark, just so the other 25 can get to tomorrow.

Q What is it about the personalities and subjects of your two previous books on Rick Ankiel (“Phenomenon”) and Jim Abbott (“Imperfect”) can you find connect with Erik Kratz?

A They were – and are – all fighters. Where Jim was immediately eloquent and thoughtful about his physical challenges, probably because he’d been a frequent narrator of his own life, I think Rick needed the experience of telling his story to come to terms with his emotional challenges.

Jim had sorted out the feelings about himself and his career as he went, or at least to a greater degree than had Rick, who’d arrive at difficult memories and often waved them away by saying, “But, whatever.” Then he’d laugh, because I’d said it so often, and he’d say, “I know, I know, when we figure out the ‘but, whatever’ we’ll have our book.”

Then they both needed some time and distance from their careers to become wholly proud of them.

Erik, like many career backup catchers, had different challenges. He was never going to be the “next” anything. While Jim and Rick eventually had to manage other people’s expectations of them and, more, their own expectations, Erik was left with slivers of opportunities, doubters and more goodbye handshakes than he could count. That forms a different kind of person, and he’d have to choose to be bitter or resilient. While there was some of the former, to be sure, he also persisted for 19 professional seasons.

Q As you point out, catchers, especially the backups, have often made exceptional MLB managers. There’s also a history of them making exceptional TV and radio analysts, because of their smartness (Jeff Torborg, Kevin Kennedy) or self-effacing humor (Joe Garagiola, Bob Uecker). Which catchers – backup or otherwise – that you see in today’s game or recently departed who could be potential star baseball TV analysts?

A Of the (kind of) recently retired, A.J. Ellis is first on my list. He is one of the brightest baseball players I was ever around. He’d also make for a terrific manager.

Erik is exceptional when he talks about today’s game and isn’t afraid to have an unpopular opinion. His work on Phillies radio was really good. Also, Chris Gimenez, Stephen Vogt, Josh Paul, Josh Thole and Anthony Recker are charismatic and saw the game from every angle.

Among current players, Travis d’Arnaud, Garrett Stubbs and Curt Casali (who is getting No. 1 work in Cincinnati) come to mind. They’re smart enough to educate and grounded enough to relate to the average listener.

Q You say at the end that the point of the book isn’t to argue that backup catchers hold “a monopoly on the human – sometimes very human – qualities we hold or would most like to see in ourselves.” You also write you’re not trying to use them as the primary example of someone who has the ultimate “hardball grit.” What do you ultimately hope readers take away?

A We all can’t be the superstar. That there is value in being a good teammate, a good friend, a kind soul. The payoff for all the hard work sometimes will be all the hard work. The reward, sometimes, is a base hit, sure, but sometimes it’s the waiver wire, too.

Theo Epstein is quoted in the book about ego, and how it’s not an athlete thing or a baseball thing or even a backup catcher thing, but a human thing that we come to accept or not. When we play/work/live for the person next to us, when we ask how someone is doing and actually wait for the answer, when we show up every day ready to play, even when we know for sure we’re not going to play, there is merit in that. In those moments, perhaps, we find in ourselves a person we can be proud of.

A.J. Ellis said that when he was first called up to the major leagues, he made himself sick worrying he was going to make the mistake that lost a baseball game. Eventually, and it took time, he was asking of himself to do one thing, make one play, come to one decision, that helped win a baseball game. He figured he wasn’t going to do it on his own. He knew that he didn’t have to. But he could be part of something that maybe only he recognized and that that would be enough for one day. Stack enough of those and he’d have himself a career he’d be proud of.

I asked dozens of backup catchers, many of whom clawed just to hit .200, what they were most proud of in their careers. To a man they said they thought they’d been good teammates. Also, that it wasn’t up to them to say so.

Q Something that doesn’t keep me up at night but I wonder about: As I watch and rewatch the film “Bull Durham” and wondering why Crash Davis never made it to the big leagues, staying in the minors for all those years. In studying the character – the words Ron Shelton gave him, and the way Kevin Costner played him – what do you think was missing from his baseball DNA? He seemed to have resilience, persistence, abilities … was he too selfish to accept a role as a possible backup catcher in the bigs?

A If I recall correctly, Crash got 21 days of big-league service time, which he wore proudly. Your point is taken. Some guys simply have nowhere else to go. Others can’t stop believing in tomorrow. Still others love the life, love the game so much they would play it forever if they could.

Let’s consider why Crash never became the quintessential major league backup catcher, though. My guess is he couldn’t hit at all, and that all those home runs must have been off mistakes they don’t make in the major leagues. (Somewhere in every backup catcher’s past is a scouting report that reads he can’t hit and won’t ever hit, and everybody but the backup catcher comes to believe it.) Start there. Because it’s one thing to hit .209 (as Erik did, with some power), and another to be a black hole. Also, Crash wouldn’t have been the first older catcher whose job it was to help raise a franchise’s next generation of pitchers. I think veteran minor-league backups also can prepare young minor-league managers and coaches for the next step, as many have been in and out of the big leagues, know the league, know how people think there, know what the egos (both hardened and fragile) look like, and finally what works in a clubhouse and what doesn’t.

Crash was going to keep playing until he found a reason not to. I’m sure he had plenty of opportunities to quit. They all do. I’m glad they didn’t.

Q One last thing: It says in your author bio: “His next book is about a storied pitcher in the league.” What’s going on there?

A To be announced!

How it goes in the scorebook

Catchers’ Perseverance

By the way: How did Angels’ backup backstop Matt Thais get called for two catcher’s interference infractions – in one inning – that led to a loss in Boston last April 15 (on Jackie Robinson Day)? And it was the third CI called in that game by the home plate ump?

You can look it up: More to ponder

== Last fall, we found, and perhaps fell in love with, “How I Found Love Behind the Catcher’s Mask,” a book of poems by E. Ethelbert Miller (City Point Press, $15.99, 80 pages, released on Sept., ’22) that features the work of the Washington D.C. literary activist.

Catch the picture on the cover? It’s the Dodgers’ Johnny Roseboro. The book’s title comes from a poem by the same name, one of more than 50 included. Merrill Leffler writes in the introduction about the title poem about how “the catcher speaking in first-person is squatting behind home plate, Buddah-like. His job: Protect the plate and give the pitcher secretive signs on what pitch to throw next … The operative word is signs. The catcher is a master of the call, the player in charge of delivering the signs – his decisions are based on many factors. … A catcher’s signs are literal and metaphoric, with its punning and nuances about the catcher’s self-conscious feelings of failure, his despairs … If you don’t know that catchers give signs to the pitcher on the kind of pitch to throw next, then signs may not radiate the nuances of the catcher’s complexity of feelings.”

Pretty deep, eh?

It follows up Miller’s first two books of poems called “If God Invented Baseball” and “When Your Wife Has Tommy John Surgery.”

== Even though the publisher has said “Tao” is coming out July 11, this is what we saw in our local Barnes & Noble on the last day of June, 2023 (above). Which is fine by us.

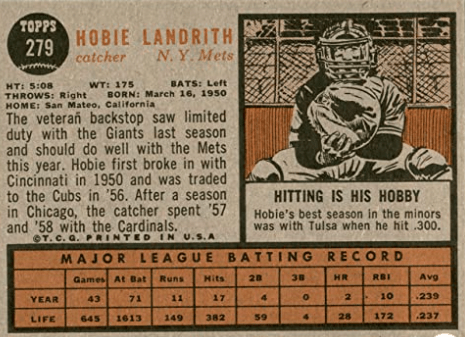

== The New York Mets’ very first player, Hobie Landrith, a “veteran backstop” who would end up as a backup catcher and then get traded away during their first season, passed away recently at 93 (despite the fact his Topps 279 baseball card says he was born in 1950, the year he broke in with Cincinnati). Here is his obit in the New York Times.

1 thought on “Day 20 of 2023 baseball books: Rye-old catchers, with no real backup plan”