“The New Ballgame: The Not-So-Hidden

Forces Shaping Modern Baseball”

The author:

Russell A. Carleton

The publishing info:

Triumph Books

304 pages; $30

Released June 13, 2023

The links:

The publishers website

At Bookshop.org

At Powells.com

At Vromans.com

At TheLastBookStoreLA

At Skylight Books

At Target

At BarnesAndNoble.com

At Amazon.com

The review in 90 feet or less

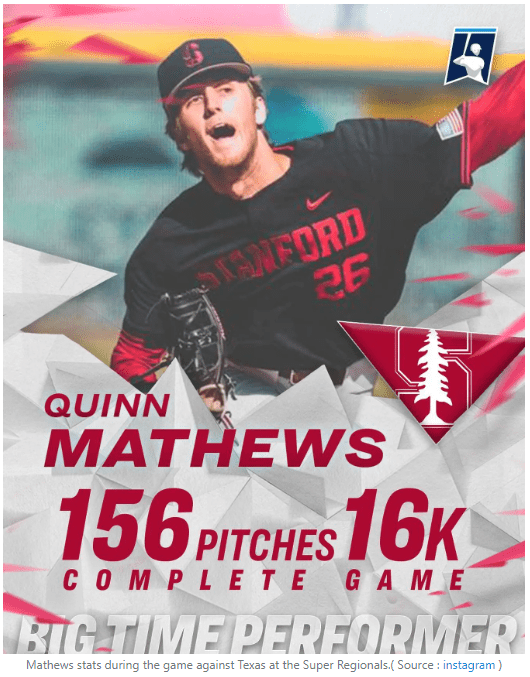

Quinn Mathews worried a lot of people recently.

Stanford’s senior starting pitcher had been pushing the limits of baseball’s accepted norms — and perhaps some common sense – as his team advanced in the recent College World Series. It all had to do with those who were counting his pitches while his teammates were counting on him to carry them on his back.

During the regular season, the 6-foot-5 lefthander threw at least 100 pitches in 15 of his 16 starts. As the Cardinal faced an elimination game against Texas in the CWS super regional, Mathews was allowed to throw 156 pitches in an 8-3, complete-game victory, which included 16 strikeouts.

That added up him throwing more than 300 pitches during three appearances over a 10-day span.

The social media debate was en fuego: Is this too much for the Mighty Quinn?

“Before people pass judgment, they don’t know what we know,” answered Stanford coach David Esquer. “We took into account that he wasn’t cranking off a majority of sliders and fastballs. He was probably throwing a majority of changeups, and we thought that lowered the stress of the pitch count.”

It led to similar handwringing when Johns Hopkins University fifth-year senior pitcher Gabriel Romano threw 164 pitches during a complete-game win during an NCAA Division III tournament game last month. Author Keith Law was compelled to post this on Twitter, followed by Romano’s response:

An NCAA rule in place today states that if a pitcher goes more than 110 pitches in a game, he can’t return to the mound for three days afterward. The rules were all upheld here.

To complete the story on Mathews: The former Aliso Viejo High standout waited eight days after his regional win over Texas to go up against Tennessee in the College World Series. He lasted just 4 2/3 innings as No. 8 Stanford was eliminated by the Vols on June 19. Matthews threw 89 pitches and held Tennessee scoreless until they batted around on him in the fifth inning.

“Quinn’s bailed us out all year,” said Stanford reliever Drew Dowd of the Pac-12 pitcher of the year.

Mathews, a 2022 19th round draft pick by Tampa Bay before he decided to play one more year at Stanford, was scooped up by St. Louis in the fourth round of this 2023 draft, No. 122 overall.

The Washington Post’s Jesse Dougherty wrote a followup about the “layered debate” caused by pitch counts with college hurlers and it quoted Jimmy Buffi, who the Dodgers hired in 2015 because of his expertise in bio mechanical engineering and effects of arm injuries.

“When you sit behind a computer to write a paper about injury risk, injury risk is your number one priority,” said Buffi, who left the Dodgers in 2019 to start Reboot Motion, a sports science company that consults for teams around Major League Baseball. “But when I joined the Dodgers, it was like, ‘Oh, crap; winning is the number one priority.’ And I think about that often: There’s always a risk-reward trade-off when the ultimate goal is winning.”

Joe Posnanski also wrote last April about pitch counts: “I’ve started to fall in line more with people who think we focus too much on the number of pitches thrown and not enough on the velocity and effort of pitches thrown. You hear old-timers talk about it all the time, but how many times in a game did Tom Seaver or Bert Blyleven or Fergie Jenkins or Jim Palmer or Jack Morris or Steve Carlton or Greg Maddux or dozens of other big-inning pitchers really air it out?* How many times did they throw a baseball absolutely as hard as they could? Ten times a game? Once or twice a game? Never?”

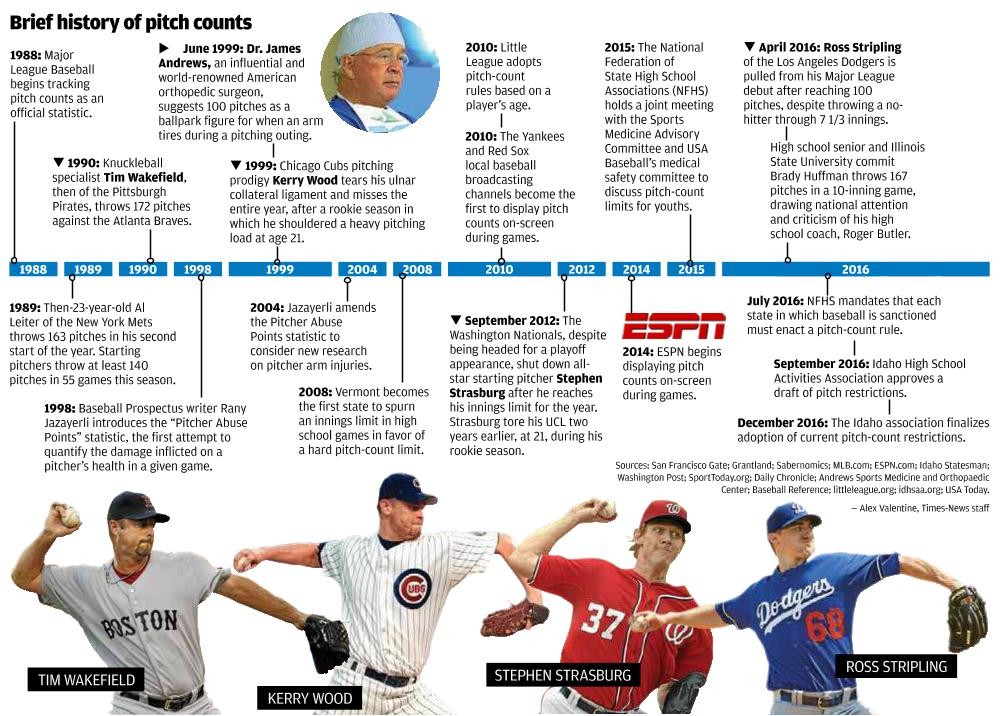

Trying to put this into context, no MLB pitcher had thrown 160-plus in a game since Boston’s Tim Wakefield registered 169 pitches against Milwaukee in the summer of ’97. Wakefield’s primary pitch was a knuckleball. Radar guns aren’t necessary to record his speed. It’s a pitch that delightfully dances to its own rhythm.

Former Dodgers left-hander Rich Hill recently threw 119 for Pittsburgh against the New York Mets, the most by any big-leaguers this season. Hill, who at 43 is the oldest player in the MLB this year, left after seven innings of a 14-7 win. Hill’s primary pitch is a slow curve ball, and a change-up off a change-up. Radar guns take a nap when he performs.

The theme here: If you’re not serving up inning after inning of high-velocity pitches that put extra stress on the arm with the required spin rates, you’re often in better shape to go deeper into the game. Even if that’s all against current conventional thinking. Thinking, that, come to think of it, could use more thinking.

To say the world is changing before our eyes in ways we couldn’t imagine, just imagine this: The Earth’s axis has been messed with lately, and we’re to blame. Meanwhile, the FAA just approved testing the first flying car, and it’s made to soar with 100 percent electricity. Which is a power source that we will continue to mine the Earth for the proper elements, which again could push the planet to extreme pushback.

Most of the time, it feels like we’re just trying to hang on as the Next Change occurs, and we don’t get a chance to catch our breath and figure out what got us here, or if the change is something that’s particularly a good thing, a necessary evil, or promises something better on the back end.

Something also dawned on us while driving past a high school summer league baseball field recently. There was a game going on. The emphasis on a game. Between two teams, between two age groups that still seemed to enjoy comradery, friendships, parents in the stands, a family atmosphere.

In contrast, major-league baseball has come to expose itself as more an entertainment business first, and a tradition that carries societal and historical significance second. It is moving further and further from a game and even pushing through resistance no matter what’s happening in the world, as we saw through the period of COVID, just as it did during World Wars — you need us as something to feel normal. Changes in the sport seem to just accentuate that goal and objective. They aren’t changes that are also happening on Little League or high school level or the American Legion level. It is still a learning experience, still a social activity.

The gap between the two version of baseball seems to be widening, and books like this emphasize that point. To win in an MLB game is to entertain. To win, one must take best care of the high-priced performers as best possible. Don’t stretch their limits. Individual performances are great, but really, we need the team to succeed. The logo. The brand.

Or as Jerry Seinfeld reminds us, we’re cheering for laundry.

Once we sort of come to terms with that distinction, it may not be easier to except, but at least it makes more sense on some levels. Major-league baseball today may not be better or worse than it was 10 years ago or 20 years ago or 50 years ago. It’s just different. Sometimes that is OK. But often it comes at the expense of something that is held deeper in our soul that we don’t realize is being shipped away up for the pursuit of something else.

Or, we could be wrong. We perhaps need a trip around the world in a flying car — and traveling against time — to think this through more.

In his follow up to a fantastic 2018 book “The Shift” (which we reviewed here and ScrewballTimes.com did as well here), Russell Carleton, a Senior Research Associate at Georgia Health Policy Center by day who was also hired by the New York Mets among other teams for his insights after his first book, is going a bit with some Darwin-esque approaches to try to explain why the current game’s trends and adjustments have evolved – or devolved — from what we’ve enjoyed and followed along with in the past, and, if you’re reading between the lines, it does have to do with trying to squeeze more fan enjoyment, and financial investment, in its entertainment factor.

In general, he writes on page 18:

“If you’ve watched the game of baseball for a few decades, you’ve probably noticed a few changes. There wasn’t a point where someone said, ‘We’re going to phase out the complete game for pitchers,’ but little by little, it happened. In this book, I want to ask, ‘How did we get here? … How did we get from the baseball of my youth to this new ballgame’?”

Specifically to the issue of the role of the pitcher changing – and why one isn’t expected to throw as many as 100 pitches or more than twice through the other team’s lineup, whichever comes first – Carleton lowers his binoculars and admits on page 82:

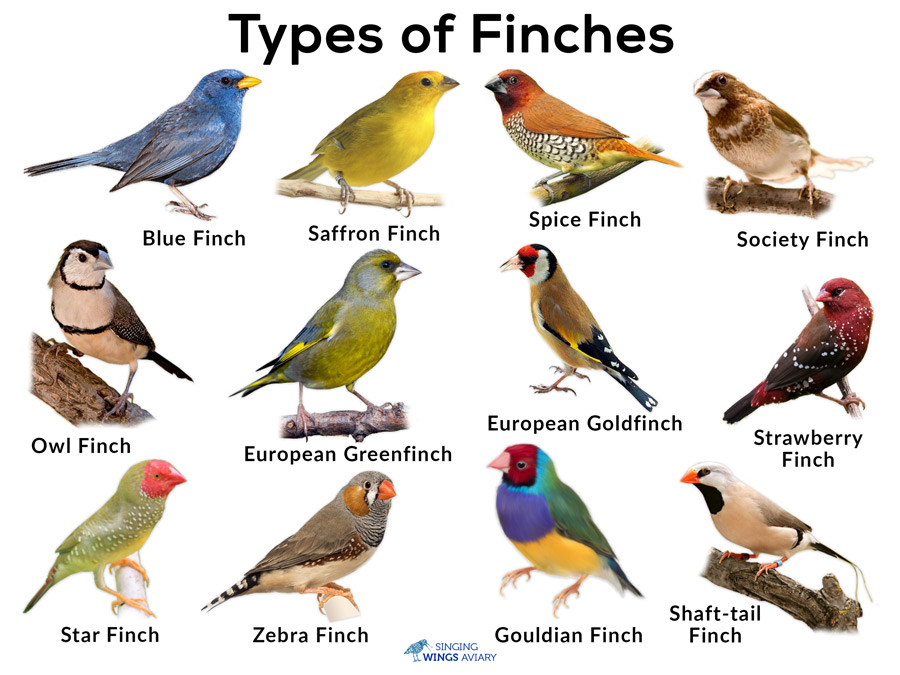

“If you want to understand the new ballgame, you have to understand the new roles that pitchers play in it. Most importantly, you have to understand the evolution of the relief pitcher as its own separate species. Sometimes within a habitat, a new finch migrates to the area and it ends up as a disaster for the eco system. The new species takes over, slowly at first, but eventually displaces many of the old animals and plants and changes all the rules. That’s called an invasive species. Reliever are a lot like that … There are a lot of people who worry about the reliever evolution because of what it’s done to the time-honored place of the starting pitcher in the game. If we’re not careful, it’s going to have other, much more devastating effects.”

Orioles and Cardinals now need to keep their heads on a swivel. Finches are near. (Maybe the way to combat it: Find the next Sidd Finch).

Carleton is more clinical explaining with charts and data why this has happened:

Page 28, Figure 2: Players are bigger and stronger and heavier. The scales have adjusted to give more weigh to those weightier.

“Not-so-hidden forces (are shaping) baseball: Baseball has evolved into a game of the arms, rather than the legs,” he explains, and then makes the astute observation: “The very name of the game, ‘baseball,’ suggests that the primary action of the game should be running the bases. That is, after all, how the points are scored. The new ballgame is moving away from that. … the act of hitting has become the priority.”

Also: The field of play hasn’t changed. It has stayed pretty much the same through the entire end of the 20th Century and into the 21st Century. Bigger, strong batters reach the outfield walls easier. And it’s encouraged – see the annual “Home Run Derby” during every MLB All Star Game.

With that fulcrum in effect, what does pitching do to counteract it?

In one respect, they match power for power by throwing harder with more strength. Carleton points out in 2022, there were 65 different pitchers who threw a pitch at 100-mph during a game.

However, in the past, those who threw hard were somewhat passed over because they “were considered ill-suited to providing enough ‘length’ in their outings … they were passed over in favor of players who were more suited to the ‘energy conservation’ style,” he writes.

Not anymore.

There is also more data, starting in 2015, that explores the speed and spin of a pitched ball, which has compelled decision makers to load up on that commodity even if it is for short bursts, and start a parade of pitchers who can accomplish that feat game after game.

As a result, a starting pitcher isn’t expected to go more than 15 outs – or twice through a lineup. More data shows that a third time through a lineup favors the batter who has seen the pitcher longer, and the pitcher should be fatiguing.

Page 79: “Pitching has evolved to a model of shared responsibility. In 2022, teams used an average of 4.30 pitchers to get through the day, up from 3.15 in 1992 and 2.55 in 1962.”

Take what happened last Saturday as an example: The Detroit Tigers’ Matt Manning (6 2/3 innings, 91 pitches), Jason Foley (1 1/3 innings, 15 pitches) and Alex Lange (1 inning, 10 pitches) combined for a 2-0 no-hitter against Toronto.

In the 2022 World Series, Houston’s Cristian Javier (6 innings, 97 pitches), Bryan Abreu (1 inning, 15 pitches), Rafael Montero (1 inning, 10 pitches) and Ryan Pressley (1 inning, 19 pitches) combined for a 5-0 no-hitter in Game 4 against Philadelphia. Then last June ’22, Javier combined with Hector Neris and Ryan Pressly on a no-hitter against the Yankees.

Talking to the New York Times about this accomplishment, Houston starter Justin Verlander pointed out: “Not to take anything away from the combined no-hitter, but you can even see in the media, just the way it’s covered,” that this thing is a different animal. And with the way the game is changing, he noted, combined no-hitters are going to become the norm rather than the exception. Indeed, 12 of the 20 have occurred since 2000, and nine of those have come since 2018.

“I hope that Major League Baseball doesn’t wait too long to address that because you get what you asked for, right?” Verlander said. “Teams are looking for players who throw 100 miles an hour and have one really good off-speed pitch. So instead of developing good pitching, as a younger player you’re obsessing over throwing the ball hard and spinning it. So you break instead of waiting for yourself to naturally develop. So you get what you ask for.”

In the 2021 World Series, Atlanta starter Ian Anderson went five innings of no-hit ball against Houston in Game 3, facing 18 batters and making 76 pitches. He was taken out. Two relievers kept the Astros hitless until their fourth pitcher, Tyler Matzek, gave up a hit in the eighth inning.

In the 2020 World Series, who can forget Tampa Bay’s Blake Snell pitching in Game 6 holding a 1-0 lead against the Dodgers through five innings. He struck out nine of the 18 batters he was allowed to face, then he was pulled with one out in the sixth inning. The Dodgers won the game, and the World Series, scoring two in the sixth and one in the eighth for a 3-1 decision – secured by seven Dodgers pitchers, none throwing more than starter Tony Goslin’s 48 to 10 batters in the first inning and two thirds. Julio Urias threw the last 2 1/3 inning – 27 pitches to seven hitters.

As Carleton writes on page 79: Research has shown that if a pitcher throws more than 115 pitches in a single outing, he bears an increased chance of injury. Still, most starters can comfortably throw 100 or so pitches in a game and have no ill effects.

(To that point, the MLB has posted this suggested template for those coaches and league trying to prevent injuries with young arms).

More and more, Carleton uses techniques he’s developed as a mental health researcher to best explain to the baseball fan laying on the couch with a pillow over his head why we’re in this current situation.

Yes, analytics influences decision making and will continue to do so until something else affects its trajectory.

Maybe, someone like Quinn Matthews can help that. And, perhaps, bail us out as he did with the Stanford team time after time last spring.

If there is a plethora of hard-throwing pitchers making up half the MLB team’s 26-man roster, why can’t a young arm that baffles the hitter with changing speeds rather than tries to overpower them have an impact to effect change?

More complete analysis, history and cognitive science may help push that along as well.

How it goes in the scorebook

Lessons learned. And already addressed.

In some ways, Carelton’s book could use an update considering all the rule changes that occurred after the 2022 and we already see in effect for the current season.

He accounts for that on page 233:

“The danger of writing a book like this is that by the time someone is reading it, the trends I’ve identified might be old news and the questions I’ve asked may have already been answered … There may be new questions that I didn’t even know to ask. Books represent a picture of a moment in history, but they stick around for years afterward. I can only hope that those years have been kind.”

They will be.

As we can see, the pitch clock pushes the game faster, and rules about relief pitchers having to face at least three batters continues to have a positive effect to that end.

Larger bases are encouraging more steals – and bringing “base” back to baseball, as rookies such as the Cincinnati Reds rookie Elly De La Cruz or the Arizona Diamondbacks’ Corbin Carroll take more center stage.

But the explanations Carleton provides that have led to those alterations remain relevant, and he’s a very credible person to walk the fan through this, again based on his 2018 book, “The Shift,” which, again, has now been eliminated – perhaps in part by his thought provoking book about it.

In the acknowledgements of “New Baseball,” Charlton writes that “The Shift” was “my mid-life crisis project. Pieces of that book edited out became material for this one as he also kept writing for Baseball Prospectus and developed ideas here.

You can look it up: More to ponder

== The primer to this book may be “A Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations that Shaped Baseball” by Peter Morris in 2006.

== Going back to pitch counts: Two other historic reference points that are often made in these kind of discussions.

First, Nolan Ryan threw 235 pitches in a 13-inning performance for the Angels against Boston in 1974, leaving with 19 strike outs, 10 walks and a no-decision. Angels pitching coach Tom Morgan had kept track of Ryan’s pitch count at the time on a hand-held clicker. Second, there’s the famous contest that pitted San Francisco’s Juan Marichal against Milwaukee’s Warren Spahn, referred to in a story by the Society of American Baseball Research as “The Best-Pitched Game in Baseball History,” and resulted in a 2011 book by Jim Kaplan titled “The Greatest Game Ever Pitched.”

Marichal, a spry 25, threw 227 pitches. Spahn, a relentless 42, threw 201, because they went into the 16th inning of a scoreless game that finally ended with a Willie Mays home run at Candlestick Park on July 3, 1963. Through the first nine innings, the two had exceeded 150 pitches.

As for wear and tear, Marichal’s complete game was one of 18 that season. He would lead the league with 22 in 1964 and 30 in 1968, piling up 244 (against 243 wins and 457 starts, spanning 16 seasons). Spahn led the National League with 22 complete games in 1963, the last year of a streak when he led the league for seven straight seasons, and nine times overall. He finished with 382 career complete games (against 363 wins and 665 games started spanning 21 seasons). He threw three complete games in his final season as a San Francisco Giant at age 44.

For comparison’s sake, Texas’ Nathan Evoldi led the American League with two complete games in 2022, two of 36 total complete games pitched last season.

As part of an essay that he wrote for the Internet Baseball Writers Association, Las Vegas-based writer and SABR member Jeff Kallman hit on two themes that were in his craw: Stop trying to bring back complete games for pitchers, and stop using the Marichal-Spahn game as a mic drop.

“For the record, Spahn — whose hardest fastball wasn’t exactly all that fast, and who developed his trademark screwball and slider late in his career — averaged 7.7 innings per start lifetime, which was exactly 1.1 more than the major league average during his career. … Marichal — with his five-pitch repertoire and fabled array of about sixteen differing windups and maybe eight different leg kicks including the famous Rockettes-high kick — averaged 7.6 a start, also 1.1 higher than his career’s MLB average.

“The Marichal/Spahn marathon was an outlier among outliers just as Hall of Famer Nolan Ryan’s entire career was an outlier among outliers. ‘Most pitchers,’ The Athletic’s Keith Law has written (in The Inside Game), ’can’t handle the workloads that Ryan did … because ‘they would break down and suffer a major injury to their elbow or shoulder, or they would simply become less effective as a result of the heavy usage, and thus receive fewer opportunities to pitch going forward. Teams did try to give pitchers more work for decades, well into the 2000s, but you don’t know the names of those pitchers because they didn’t survive: they broke down, or pitched worse, or some combination of the above.’

“We celebrate games such as as Marichal/Spahn, or Harvey Haddix’s busted 1959 perfecto in the 13th inning, because they were outliers … So quit using those games, or Nolan Ryan’s career, as the measurement. The actualities have always been different, which the harrumphers might have discovered or re-discovered if they’d done their homework before shooting their tweeters off.”

When I write/oversee SABR Games Project articles, I’m always looking for pitch counts in pre-1988 games, either when they were mentioned in the newspaper or when they can be counted from a recording of a TV or radio broadcast. It’s interesting to see how modest the pitch counts often were, such as on Opening Day 1979 (for which I had the benefit of a radio broadcast recording…), when Bert Blyleven threw 102 pitches in seven innings and Steve Rogers threw 96 in eight innings of Montreal’s 3-2 win over the Pirates:

https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/april-6-1979-expos-edge-pirates-in-10-inning-season-opener/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Authors have pitch counts as well. As in, pitching a book idea to a publisher. Ironically, it takes far more pitches these days to get any sort of traction. Russell has a great track record so far that publishers are now pitching him for more ideas.

LikeLike