“Smart, Wrong and Lucky: The Origin Stories

of Baseball’s Unexpected Stars”

The author:

Jonathan Mayo

The publishing info:

Triumph Books

256 pages; $28

Released July 11, 2023

The links:

The publishers website

At Bookshop.org

At Powells.com

At Vromans.com

At TheLastBookStoreLA

At Skylight Books

At BarnesAndNoble.com

At Amazon.com

“Baseball’s Endangered Species:

Inside the Craft of Scouting by Those Who Lived It”

The author:

Lee Lowenfish

The publishing info:

University of Nebraska Press

344 pages; $34.95

Released April 1, 2023

The links:

The publishers website

The authors website

At Bookshop.org

At Powells.com

At Vromans.com

At TheLastBookStoreLA

At Skylight Books

At BarnesAndNoble.com

At Amazon.com

The reviews in 90 feet or less

A headline in the June 21, 2023 edition of the Los Angeles Times: “Scouts sue MLB for age discrimination, claiming the league had a ‘blacklist’“

Heavy sigh. The news shouldn’t have been a surprise at this point in baseball’s wobbly course of history.

More than 17 plaintiffs seek about $100 million. More scouts will likely join this class action suit. Especially those who believe they were wrongfully released from various MLB teams because of their age – not to mention perceived usefulness.

Analytics and technology have been gaining momentum as important amateur player assessment tools. The eyes don’t always have it any more from the physical scouts who do all the legwork, travel, take notes, cross check and then make their case. Budgets are tightened (even if more data shows teams are back to basically printing money) and the size of the draft has also reduced – it used to go as long as teams kept wanting to pick players.

As columnist Jim Alexander of the Southern California News Group recently asked about this situation: So what happens when you give your life to something and then find out it has no more use for you?

Coming from a newspaperman, that carries plenty of weight. And baggage. In a sense, scouts seem to be seen as essential to MLB teams as box scores are to newspapers. They take up too much space. There are other ways to get information. They have a use, but just not here.

The timing of these two books can help us better understand the history scouts have created for a game that seems to be trying to push the pendulum too far the wrong way … to correct an error? Or exacerbate flawed logic?

We’re still pouring over data and bios and assessments of what happened with the 2023 MLB Draft last weekend in Seattle. We listened to analysis by those on the MLB Network and ESPN who study these things and know the system well – understanding that it remains a rather inexact process when compared to the NFL or NBA drafts. It’s again time to pay more homage to how decisions get made and how much is based on a feeling in a scout’s gut that may not always line up with the numbers.

Our previous experiences working on stories involving the business of scouting led to finding out more about the annual Professional Baseball Scouts Foundation event in Beverly Hills, a group co-founded by former player agent Dennis Gilbert in 2003.

“In the Spirit of the Game” brings some of the game’s biggest names to draw attention to PBSF. Gilbert was recognized for his philanthropic efforts in 2016 with the MLB Dave Winfield Humanitarian Award for launching PBSF, as well as at the 2022 December Baseball Winter Meetings when he was given the Baseball Assistance Team Frank Slocum Award.

Because even if they manage to keep their jobs, scouts don’t last forever. And they can fade away fast these days. Their families could use help and Gilbert has been there to do so.

That led to a profile we did for the Long Beach Post in 2020 about RJ Harrison, honored by the PBSF for his career as a scout for 30 years, then moving up into the ranks of the Tampa Bay Rays as a senior advisor for scouting. His father, Bob, was recognized by the PBSF in 2011 for his life’s work as a scout. In 2006, RJ Harrison convinced the Rays to take a leap of faith with their third overall pick and nab a third baseman out of Long Beach named Evan Longoria (now 37, out of Long Beach State, with a career WAR of 58.8). The 2008 Rookie of the Year pick and a three-time AL All Star after his first three seasons worked out pretty nicely — even if the Rays did commit to him ahead of Clayton Kershaw (to the Dodgers at No. 7), Tim Lincecum (No. 10 to San Francisco) and Max Scherzer (No. 11 to Arizona). The three of them, however, aren’t close to Longoria’s 1,912 hits or 342 career homers.

In Smart, Wrong and Lucky – the three most likely outcomes in how a baseball scout gets judged — the focus is on career beginnings of eight well-known players and how each provided a different example of their entry point into getting drafted, and then having noteworthy success on the big-league level.

Jonathan Mayo, a longtime writer at MLB.com focused on the draft and minor-league prospects, can tap into his deep resources to find instances of how, as he says in the intro, “scouts are the foundation of baseball and it is grossly underestimated just how hard they work and how inexact a science it is to find the national pastime’s future.” It’s why Mayo picks players who weren’t the obvious first-rounders who didn’t measure up, but focuses more on later-rounders that exceed expectations and allows the scouts to tell their stories “about their favorite ‘finds’.”

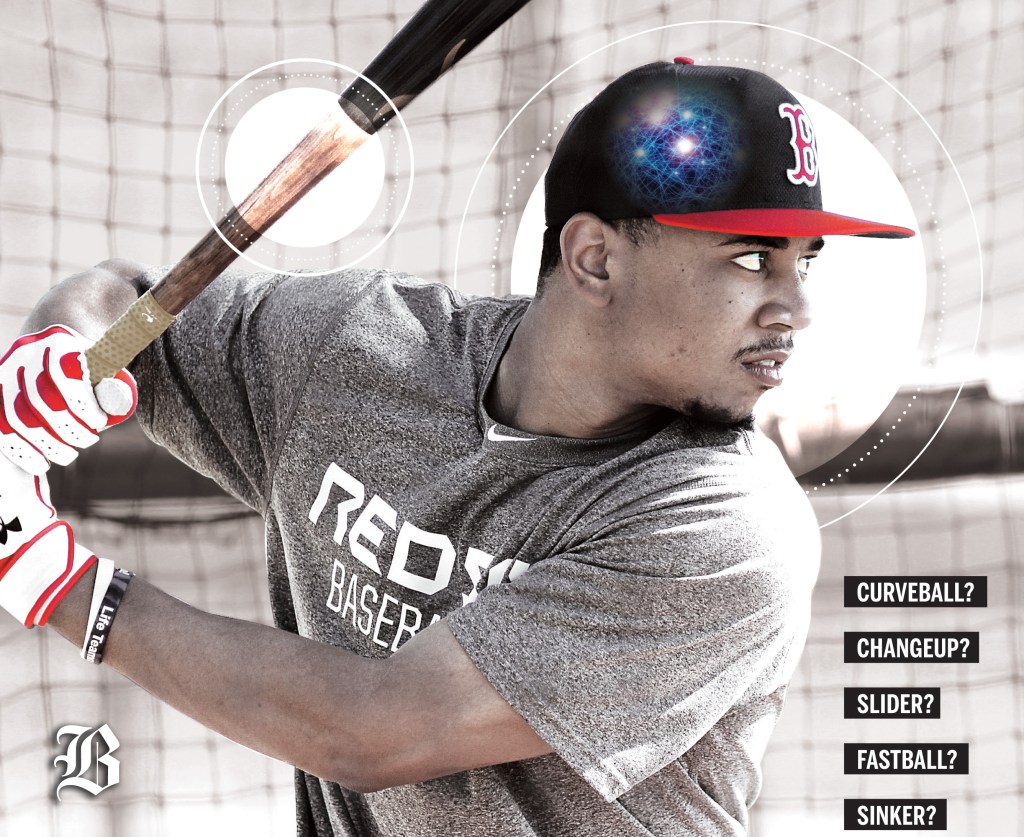

Mookie Betts – the 2011 fifth-round pick (No. 172 overall) by the Boston Red Sox out of high school in Nashville, Tenn., tabbed as a shortstop with the design of making him a second baseman – was the chapter we initially gravitated toward. We wanted more background on how the Dodgers’ current All-Star right fielder (who has finally been playing more shortstop and second base and enjoying it) showed persistence in developing his athletic talents (which also revealed themselves in basketball and bowling) that continue to evolve in making him one of the most feared lead-off hitters in the game’s recent history.

The story goes that if the Red Sox hadn’t kicked in a $750,000 signing bonus, Betts was ready to go play at the University of Tennessee, a bargaining leverage high school players still have with them these days. And if the Red Sox hadn’t jump on him at that moment, they feared the San Diego Padres, which also scouted him thoroughly, were ready to pounce.

The Red Sox used “good old-fashion scouting and some new-fangled approaches” to figure out Betts’ worth, Mayo reports. Red Sox area scout Danny Watkins was the point person. As he knew the bigger names were at nearby Vanderbilt University – 12 were taken in that 2011 draft — he still was able to travel to see Betts in high school, sit with him, talk to his parents, cultivate a relationship. Also confirming Watkins’ reports was Tom Allison, a cross checker who in 2021 joined the Dodgers as a special assignment scout.

“The one thing that I noticed about Mook was number one, he was extremely comfortable on the field. He could do anything without much effort,” said Watkins. One of those things: At a baseball showcase in 2010, Watkins saw Betts playing shortstop, go behind the bag to flag a ground ball and then flip the ball behind his back for a perfect toss to second base.

Watkins found more info about Betts’ athletic abilities watching him play high school basketball, more a sense of his competitiveness and athleticism. Although Watkins projected Betts as a middle infielder, he strategically slotted him as a shortstop – an important position – to convey why Betts was worthy of assessment. Also, the Red Sox already had a solid second baseman in Dustin Pedroia, so Betts would need to crack the lineup elsewhere.

Watkins also had a new analytic tool to try out on Betts: NeuroScouting, a company that simulated decision-making reaction time, was just starting out and Watkins had Betts try the test – when you see the ball on the screen, hit the space bar. If you see the seams going one way, tap it again. Betts tested very well, but the Red Sox didn’t know how to factor it into their assessment with a lack of historical data.

How Betts went all the way to the fifth round is the other part of the puzzle that isn’t always easy to assess in the moment as names flash by and voices are heard. The Red Sox actually had four of the first 40 picks – and still waited on Betts as the scouting director Amiel Sawdaye had the final call. Cal State Fullerton pitcher Noe Ramirez had enamored a few Red Sox scouts, so he was taken in the fourth round. But the Red Sox were now worried the Kansas City Royals would take him early in the fifth round. They did pick a high school shortstop – Patrick Leonard, who never made it to the big leagues, and 16 picks later, Boston took Betts.

“I almost lost him,” Sawdaye said of the Betts pick in hindsight. “If you really sift through the reports, we probably should have taken him in the first or second round.”

Revisionist historians may now say that if the Pittsburgh Pirates had a do-over with their No. 1 overall choice in that ‘11 draft, Betts should have been the choice. Really? They didn’t do all that poorly nabbing UCLA pitcher Garrit Cole. And Betts really wasn’t a proven commodity.

The fact that the 2023 MLB All Star game began with Cole as the starting pitcher for the AL team representing the New York Yankees and coaxed a ground out to second from Betts, hitting third in the NL All-Star lineup representing the Dodgers, is another reminder that no matter what teams take the leap of faith on a player, they often don’t have the means to keep him for a very long period when other teams can fight for his free-agent services.

The 2011 draft has also been categorized as one of the most successful in recent MLB history. The first round (officially 60 picks with compensation and supplemental choices) included Anthony Rendon, Francisco Lindor, Javier Baez, George Springer, the late Jose Fernandez, Brandon Nimmo, Sonny Gray, Tyler Anderson, Matt Barnes, C.J. Cron, Joe Panik, Trevor Story, Joe Musgrove and Blake Snell. Later, came Marcus Semien (sixth round), Blake Treinen (seventh round), Kyle Hendricks (eighth round) and Chris “Devo” Devenski (25th round, 771st overall, out of Cal State Fullerton who made the 2017 AL All Star team for the Houston Astros, finished off a combined no-hitter for Houston against Seattle in August of 2019, had Tommy John surgery and how plays for the Angels).

It was also the last year when MLB teams could throw endless amounts of money at draft picks in hopes of having them sign. The next year, restrictions went into place.

The MLB draft that once went 100 rounds (only because the Yankees wouldn’t stop picking), was cut to 50 rounds by 1998 and this would be the final year it went that long. It was cut to 40 rounds in 2012, and then to its current 20 rounds since the 2019 Collective Bargaining Agreement.

So no more stories about Mike Piazza as the fabled 62nd round draft pick (1,390 overall) by the Dodgers as a favor to his family in 1988. Or Keith Hernandez as a 42nd round pick in 1971 (776th overall) by St. Louis. They can still use people like Albert Pujols as someone whose talents were doubted and became a late-round example – he was the 18th choice of the 13th round by St. Louis in 1999, number 402 overall.

Pujols’ story in Mayo’s book is the one we know ended with his retirement as a Cardinal in St. Louis after the 2022 season – where he was awarded the NL Comeback Player of the Year as he launched 24 homers to go with 68 RBIs at age 42 in 109 games to finish his 22nd season. An 11-time All Star and two-time NL MVP hit 222 of his 703 career home runs during his 10 years with the Angels (and 12 more homers with the Dodgers in the second half of 2021). He is eligible to enter the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2028.

But it’s Mayo’s explanation of how Pujols came to the U.S. from Puerto Rico, laid low playing for American Legion teams in Independence, Missouri, and had most scouts worried about his body size and shape – the young man growing into his frame.

“Scouting players can be a merciless business,” Mayo writes, “and sometimes draft prospects can be described more as cattle than human beings. But when you’re in the business of trying to project what a player could become, evaluations on body type are important. And Pujols, at age 19 in junior college, would have classified as a ‘bad body’ player who was seen as a bit soft.”

Pujols had an ally in Tampa Bay scout and Cuban native Fernando Arango. Mayo points out that at various times, the Rays sent out veteran scouts such as Stan Meek and RJ Harrison – remember our mention of Harrison earlier? Neither saw in Pujols what Arango saw, even after bringing him to Tampa for private workouts. They even tried him out as a catcher.

Mayo also clears up any fact/fiction tales about Arango’s involvement in campaigning for Pujols – and Arango’s passing in 2019 precludes Mayo from asking him more about it.

How did the Cardinals end up with Pujols? They had seen him more because of his proximity to St. Louis, and at that point in the draft, the team was picking corner infielders to fill a need.

“How does he get to the 13th round?” asks John Mozeliak, who was then in the team’s scouting operations department and now is the Cardinals’ president of baseball operations. “We know we were lucky.”

In the aptly titled “Baseball’s Endangered Species: Inside the Craft of Scouting by Those Who Lived It,” Lowenfish expands on research done and documented in his previous books, “Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman” in 2007, and “The Imperfect Diamond: A History of Baseball’s Labor Wars” in 2010.

He has also been member of SABR since 1976 and posted something that still makes us giggle at the headline: “Eyeball to Eyeball, Bellybutton to Bellybutton: Inside The Dodger Way of Scouting” from 2011.

The value of Lowenfish’s tribute to scouts is a reminder of how advanced scouts work for the teams during the playoffs to assess potential opponents and how they match up closer in real time versus past performances. Because, in trying to explain how Kirk Gibson hit his 1988 World Series Game 1 homer, there’s always going to be the story attached to Dodgers advanced scout Mel Didier who … you know the rest.

“It remains to be seen whether ‘eyes and ears’ scouts will make a comeback in the foreseeable future,” writes Lowenfish. “It seems like the analytic wave is only starting … Older scouts possess such great wisdom that the missed opportunity of younger players and scouts to learn from them is a tragedy. … Houston Astros manager Dusty Baker has compared veteran scouts to the blue musicians who passed down their tradition over the generations …

“I have written this book to make sure that their voices from past and present will not be wholly lost.”

And we are ever grateful.

It starts with trying to figure out: Who’s the person in the Dodgers uniform on the cover of Lowenfish’s book? It kinda looks Ralph Branca-ish, right? Or maybe it’s Gregory Peck on the set of “The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit” as he’s doing some research for an upcoming role in a baseball movie.

You’ll have to do some research to discover it’s Tom Greenwade – introduced on page 73 – who was one of Branch Rickey’s top men and then stolen by the New York Yankees in December, 1945, just two months after the Dodgers signed Jackie Robinson from the Kansas City Monarchs.

Lowenfish writes: “Greenwade secretly scouted Robinson for the Dodgers during Robinson’s brief 1945 season with the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro League. He filed a report saying that he was a great athlete and competitor but didn’t have the arm and footwork for shortstop. Two years earlier, Greenwade had been sent by Rickey on another secret mission to Mexico to evaluate another possible racial pioneer, infielder Silvio Garcia. Nothing came of that plan because Garcia was drafted into the army by his native Cuba.”

Greenwade grew up in Missouri, pitched in the minors, worked for the IRS during the Great Depression and got onto the staff of the St. Louis Browns. In 1940, the Dodgers recruited him to Brooklyn and he was credited with helping to sign Pee Wee Reese, Gil Hodges, Cal McLish and Rex Barney. With the Yankees, Greenwade recommended players such as Hank Bauer, Elston Howard, Bobby Murcer, Ralph Terry and Bill Virdon.

“Greenwade realized that makeup, the ability to rise to the occasion in stressful situations, was a vital key to success on the Major League level.”

Oh, and Greenwade became best known for signing a Commerce, Oklahoma, high school shortstop named Mickey Mantle. Greenwade worked with his father, Mutt Mantle, and history happened.

We also find stories of Charley Barrett, an anchor of the St. Louis Cardinals’ scouting system who, in 1933, signed infielder Rosey Gilhousen after he pitched a no-hitter for Compton JC. Gilhousen hurt his arm early in his minor league career. He went into the movie business and worked for Gene Autry. When Autry bought the Angels in 1960, he hired Gilhousen as his first scout, a job given to him by Roland Hemond. Gilhousen would end up working for the Kansas City Royals and was instriumental in signing George Brett and Dan Quisenberry.

Chapter 5 is devoted to the career of Gary Nickels, whose decades long career as a scout was capped off working with the Dodgers’ Logan White, who had once mentored, who played a large role in drafting Clayton Kershaw in 2006 out of high school in Dallas as well as confirming the talents of eventual Dodgers shortstop Corey Seager and outfielder Cody Bellenger. Nickels spent 50 years in the game and was honored by the Dodgers at Dodger Stadium in 2021. He has a 2020 World Series ring from the Dodgers.

Asked what his favorite memory of his career, Nickels said: “It was the job of being the person that saw the player before they became what the public knew them to be.”

How they go in the scorebook

No need to cross check. These two are first-round picks.

Lowenfish also deftly used a spectacular line in his introduction that also must be noted. He points out that Greg Morhardt, the Angels’ scout who signed Mike Trout, once said about the business: “I look for dogs who play checkers … We’re looking for the unique,” citing a story Fabian Ardaya did for The Athletic in 2019 about how Trout became the franchise’s centerpiece.

After finding the story, there’s another quote we loved — what Morhardt remembers telling Angels scouting director Eddie Bane months before the 2009 draft about Trout:

“Eddie, if we don’t do this one, we’ll regret it the rest of our lives,” Morhardt said.

The Angels somehow got him at No. 25 overall. Ten years later, the future Hall of Famer signed a 12-year, $426.5 million contract extension that effectively made him an Angel for life.

For better or worse.

As for that 2009 MLB draft: Stephen Strasburg went to Washington at No. 1 overall. Dandy. A three-time All Star and a World Series champion. Because of compound injuries, he has won only one game over the last four seasons since signing a seven-year, $245 million contract after that ’19 World Series title. The $35 million annual average value of the contract was at the time the largest amount received by a pitcher in MLB history.

Zach Wheeler and Mike Minor went Nos. 6 and 7 to San Francisco and Atlanta, respectively and eventually made All Star squads as members of other organizations (Wheeler in 2021 for Philadelphia, as the Giants traded him in 2011 to the Mets for Carlos Beltran; Minor in 2019 for Texas, and after time with six different teams, he’s still available for hire). Aaron Crow (No. 12, Kansas City), A.J. Pollack (No. 17, Arizona), Shelby Miller (No. 19, St. Louis) and Kyle Gibson (No. 22, Minnesota) also made All Star teams.

The Angels actually took Randal Grichuk, a high school outfielder from Texas, at No. 24 before selecting Trout with two compensation picks they had back to back for losing free agent reliever Francisco Rodriguez to the Mets and first baseman Mark Texiera to the Yankees.

Five outfielders were picked ahead of Trout.

Oh, and after Trout:

Nolan Arendondo, second round, No 59 overall, to Colorado.

Paul Goldschmidt, eighth round, No. 246 overall, to Arizona.

J.D. Martinez: 20th round, No. 611, to Houston.

So there you go.

3 thoughts on “Day 24 of 2023 baseball books: More scout’s honors, especially those ‘Moneyball’-ed off the payroll”