“Mallparks: Baseball Stadiums and

the Culture of Consumption”

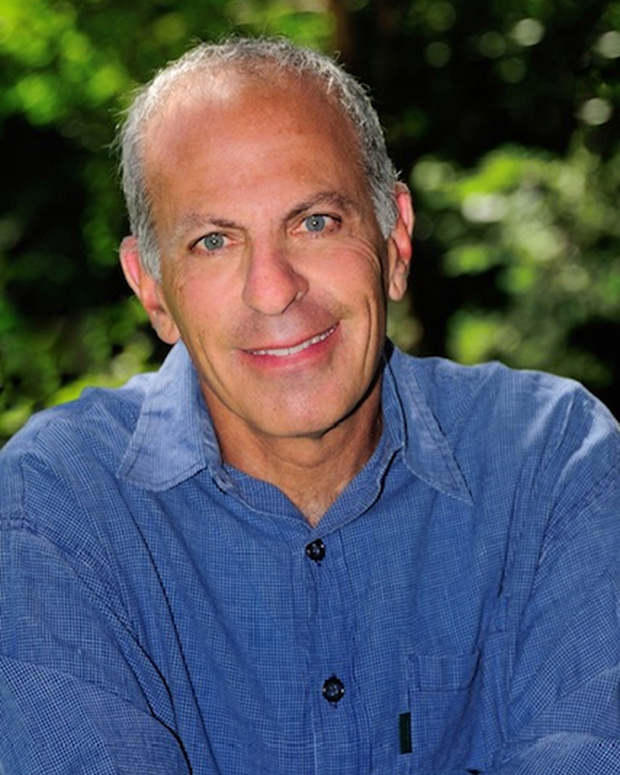

The author:

Michael T. Friedman

The publishing info:

Cornell University Press

324 pages, $49.95

Released July 15, 2023

The links:

The publishers website

At Bookshop.org

At Powells.com

At Vromans.com

At TheLastBookStoreLA

At Skylight Books

At BarnesAndNoble.com

At Amazon.com

“Game of Edges: The Analytics Revolution

and the Future of Professional Sports”

The author:

Bruce Schoenfeld

The publishing info:

W.W. Norton & Co.

272 pages, $30

Released June 6, 2023

The links:

The publishers website

The authors website

At Bookshop.org

At Powells.com

At Vromans.com

At TheLastBookStoreLA

At Skylight Books

At DieselBookstore.com

At BarnesAndNoble.com

At Amazon.com

The reviews in 90 feet or less

In June of 2020, right as the pandemic lock-down made everyone somewhat delirious, Los Angeles Angels owner Arte Moreno announced intentions to do a deal that not only would include the purchase of the original Anaheim Stadium (now Angel Stadium) and the land that surrounds it (mostly parking lots) from the city, but go forth with its long-rumored development of restaurants, shops, hotels and office space. Maybe a park or two. The plan could even knock down the park and edge it closer to the 57 Freeway and a large train station.

For the Angels, it’s all about their potential.

It would expand its footprint with a real estate pivot to enhance the value of a facility built primarily for them, aka The Big A, in 1966, which originally cost the city of Anaheim about $24 million.

For what it’s also worth, those plans are all on hold.

A city council corruption case blew up in their faces. Maybe for the better.

Moreno, who sniffed around about selling of the team last year, may now want to take a deep breath and figure out if a multi-year contract investment in Shohei Ohtani has more shorter-term value that could lead to this long-term expansion plan. Sure, it doesn’t have to be an either/or proposition. Both seem to have some bankable overlap.

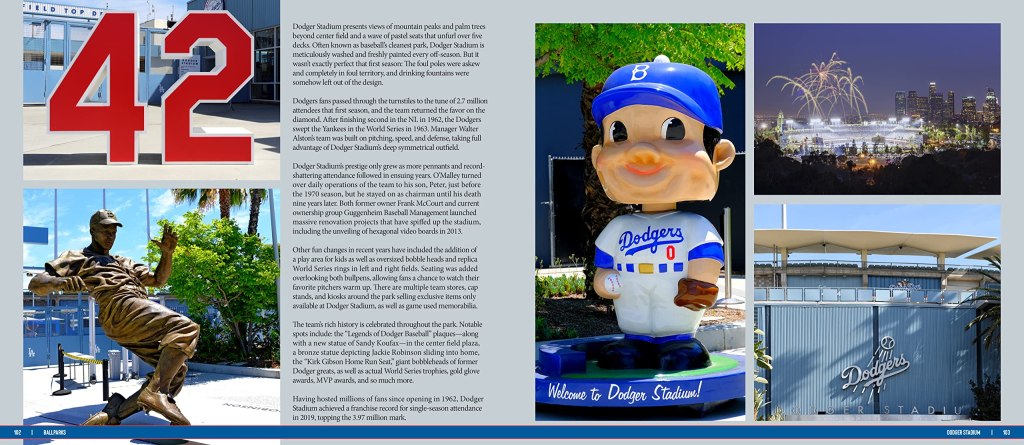

The Angels’ news came a year after the Dodgers broke open a $100 million renovation plan, in June of 2019, that essentially connected all the levels of the stadium for better fan flow, as well as create a center field plaza that had more food, beer gardens, sports bars and musical platforms. No more separation of access. Now, the place had a “front-door” entry point that wasn’t part of the $18 million construction back in 1962.

For the Dodgers, it’s all about being more provincial.

It has done several sorts of retrofits on the retro-‘60s style facility that has managed to keep its “Wonder Years” vibe but still move forward with the needs and wants of modern-day fans.

The Guggenheim ownership team called this run-up to the 2020 MLB All Star Game as a “modernizing” and “upgrading” project, exceeding $350 million in costs. COVID canceled that event (the Dodgers got the 2022 game instead to show off its work) and it made for the reopening a bit of a thing unto itself when fans were welcome back.

This was really taking the idea forward that former owner Frank McCourt couldn’t complete. He had his own $400 million facelift project that was supposed to include restaurants and shopping, but that imploded when McCourt went bankrupt, sold the team off at auction, and somehow sneaked in a deal to keep the parking lots – the prime real estate for that kind of commercial expansion.

The Dodgers are amidst a new business mindset to “rip up the blueprint,” as described in a 2019 USA Today piece by Bob Nightengale. It means more than just an entertainment district, with night clubs and sports bars, but a place people can come year around to blow their paychecks.

“It’s not so much people interested in the statistics of baseball, but Fortnite, League of Legends, Snapchat, Instagram, Pinterest, the immediacy of the environment, the gamification, fantasy, gambling and the social aspects of the narrative,” said one of the owners, Hollywood movie producer Peter Guber.

“If you don’t grow new tomatoes, you’re not going to have much marinara sauce in the future.’’

Now we can ask: Who’ll end up first with eggplant parmigiana on their faces?

The evolution of Angel Stadium and Dodger Stadium – both are somehow without a corporate naming rights deal to tarnish their purity – could be charted on a graph that looks like dueling roller coasters trying to out-dazzle the other. Neither appear to be finished with the ups and downs.

Both have their eye on a similar prize that has been sweeping MLB ballparks the last few years: Giving fans a reason to come more often to the general area, spend money, do more than just watch a baseball game from their seat, and then tell their friends about what a lovely experience it all was.

Because, in the 21st Century, that’s how we roll. Ballparks have morphed into shopping malls — which, as a stand-along concept, may be waning. But in the thought process of how to attract the next wave of consumers, seeds have been planted for a cutting-edge halo effect of supporting gambling parlors.

Hence, the titles of these books we have read with parallel interest.

If someone still has to tell you that this is all a business, and to find an answer to any of it is an invitation to follow the money, you haven’t been paying attention.

In “Mallparks,” Michael Friedman is circling back with another startling reminder that it is a multi-layered scheme preying on your frog-in-the-slowly-cooking-hot-water acceptance.

Friedman, an assistant research professor in the Physical Cultural Studies Program at the University of Maryland’s Department of Kinesiology, has done all sorts of work focused on the relationship between public policy, urban design and professional sports. His academic bio says: “By examining sports facilities such as stadiums and arenas, he is concerned with the ways in which space expresses and (re)produces power relationships, social identities and society structures.”

In what appears to be an expanded work based on his chapter titled “Mallparks and the Symbolic Reconstruction of Urban Space” for a 2016 book called, “Critical Geographies of Sport: Space, Power and Sport in Global Perspective” (Routledge, 272 pages), Friedman uses Dodger Stadium as one of his primary Exhibit A test cases.

It culls from two of our favorite books on the subject of Dodger Stadium and its relationship to Los Angeles — Jerald Podair’s 2017 “City of Dreams: Dodger Stadium and the Birth of Modern Los Angeles” (Princeton University Press, 384 pages, $38) and Paul Goldberger’s 2019 “Ballpark: Baseball in the American City” (Knopf, 384 pages, $37.50)

Friedman also brings names such as Henri Lefebvre (likely not related to the former Dodgers’ second baseman) and George Ritzer into the conversation, explaining their theories of spatial existence in relation to enhancing consumption.

A ballpark today is just following the principals of a theme park and/or shopping mall – make it quick and easy for people to enter, eat, drink, be entertained, and pay their tabs in an efficient manner. Keep the lines moving. Or, in today’s world, make it more app friendly (at the expense of older patrons) and dynamically challenge those who can’t get their heads around the fact so many others around them have their faces glued to their phone screens.

The Dodgers are connected here because of the hiring of Janet Marie Smith to do their redesigns. She is the primary force of the Baltimore Orioles’ game-changing Camden Yards facility, which some call the start of the “McDonaldification” aesthetic alteration of the MLB experience. As a result, Boston’s Fenway Park, Washington’s Nationals Park, Atlanta’s Truist Park and Minneapolis’ Target Field are held up by Friedman as more examples of what’s been presented as progress.

Minneapolis is the most interesting example, since its former park, Metropolitan Stadium, was torn down and replaced by the Mall of America. Remnants of the stadium – home plate, and a seat the Harmon Killebrew once planted a home run on – are there as part of the interior decoration. A memory. Very distant.

Dodger Stadium, meanwhile, has been in the same place and looking in many ways as it did when it was finished by the O’Malleys to house both the Dodgers (who played their first four years at the Coliseum upon moving to L.A.) and the Angels (who called it “Chavez Ravine” so they wouldn’t be promoting the rival team, then changed their moniker to the California Angels in ’65, and then bolted to Anaheim.) But it’s also quite a bit different –modified — as seats have been moved closer (and become more expensive), foul territory eliminated, suites added in place of club-level sections, and the constant feeling that every inch seems to be monetized in ways it wasn’t before.

There are also now ways a fan can spend more and upgrade his experience – not unlike a Disneyland fast pass.

A slippery slope? Friedman argues we’ve been in this free fall even if we’ve been having fun not noticing it. Raze and rebuild – which may sound familiar to former Ravine residents around Dodger Stadium – has produced, by Friedman’s observations, “hermetically sealed theme parks and wholly formed, corporately governed towns. … It would not be surprising that as teams receive development control over the neighborhoods surrounding stadiums, they also attempt to impose a similarly ordered ersatz urban environment.”

Dodger Stadium is a privately owned park. Angel Stadium is owned by the city (for now).

We’ll see how that all goes.

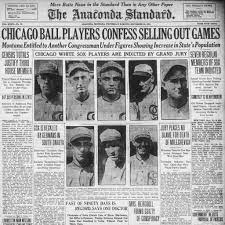

In “Game of Edges,” Bruce Schoenfield takes an overarching look at how sports and teams are looking for all sorts of ways to use analytics and get an advantage over another. But in the example he uses to fill Chapter 8 — titled “What Are You So Afraid Of?” — the focus on how the Chicago Cubs ownership has made Wrigley Field part of an expansion of the DraftKings’ brand and its sports wagering existence only re-emphasizes the point Friedman has made, to perhaps our own detrement.

Think of it just as fan consumerist going to another toxic level. Not just extracting income, but giving hope you can earn it all back.

The DraftKings Sportsbook that broke ground in June 2022 and actually opened last month is next to the Cubs’ warm-and-fuzzy historic landmark. The place looks as if it fits in, but it has a stench of Biff Tannen’s Pleasure Paradise Casino & Hotel from “Back to the Future II” (And for those who don’t remember: The Biff-man successfully legalized gambling in 1979 and was able to build his place near the sign “Hill Valley – A Nice Place To Live,” now full of bullet holes).

Schoenfeld deftly explains how the Cubs will get taxes, rent and a take of the place’s food and beverage, but none of the betting income. DraftKings knows people can wager on their phone apps, but wants this to exist in a 22,000-square-foot communal gathering experience and, as Schoenfeld writes, “watching games on absurdly large 2,000-square-foot television screens … participating in special promotions that would be made available only to those present.”

It’ll be a year-round place that team ownership knows fans in the offseason will be inclined to “walk around the corner and buy Cubs merchandise or tickets for a future game. That might be the catalyst for a lifelong relationship with the club,” Schoenfeld points out, sincee older fans are disappearing, and younger fans, who enjoy this wagering engagement, have a reason to leave their dwellings.

“It all makes sense,” Schoenfeld writes, “unless you had been following sports for longer than, say, the past five years.”

That’s because of the obvious-to-us history lesson: This is all happening just about 10 miles away from the place where baseball almost collapsed under the Black Sox Scandal. The fallout prompted an aversion of sports leagues to have anything affiliated with gambling. It only lasted a good century.

Corruption be damned. It’s old news. And who reads newspapers anyway now?

The thing that marketers call “sports wagering” and amplifying fantasy leagues is the finical driving engine for sports leagues it seems. How soon do the Dodgers and Angels buy into that with their modernization angles?

Depends on if California voters keep rejecting ballot propositions trying to legalize sports wagering.

“At the same time, the human cost of all of this, in terms of lives altered by financial losses and destroyed by gambling addictions, was impossible to know,” Schoenfeld writes in the wake of New Jersey and New York approving digital sports betting. “Gambling, the oldest, most popular and most profitable form of analytics ever applied to sports, had already profoundly affected the way that fans perceived the games they watched,” Schoenfeld adds.

As well as the human cost in watching our baseball teams trying to figure out new ways to make us enjoy spending our cash, credit and crypto currency.

Going back again to the Dodgers and that 2019 expansion plan pre-COVID: As more artistic renditions of the renovation came forward, it was noticed that Dodger Stadium included a video ribbon screen that could post odds on MLB games as well as other sports, “suggesting the team could use the spaces (set aside overlooking the bullpen, but not the field, beneath the pavilions in right and left field) as a sports bar and sports book,” as the Los Angeles Times reported.

“It’s a rendering for the possibilities and the capabilities,” Dodgers president Stan Kasten said at the time. “Right now, it is for sure, for the foreseeable future, going to be sports bar areas. And there is an awful lot of business for sports bars. Trust me, we can’t have enough sports bars.”

Yes, we can.

This isn’t raising the bar. It’s lowering the standards.

If Dodger Stadium really is in the process of getting “more beautiful with age,” we think that leaves too much wiggle room for the age-old question of how do you define beauty.

How it goes in the scorebook

We grin and bear it a bit when we see Friedman’s book full of angst about how consumerism has conflated the game’s lore, and its publisher asking us to pay $49.95 for the rights to own one copy.

We willingly forked out full price (surprised to also see it available for sale at the otherwise deep-discount-famous Walmart). We consumed it with relish. We’re now set on hanging onto it and possibly donating it someday to a library that could be part of either the Dodgers or Angels’ future stadium expansion.

Is resistance futile when it comes to ballpark consumerism? If not, this seems to be your wake up call.

These aren’t as judgmental as they are educational, documentation of what’s happening before our eyes (whether we want to believe it or not) rather than a celebration.

We are a bit more saddened by the whole thing, and wiser for the knowledge.

Also consider this just isn’t a U.S. thing.

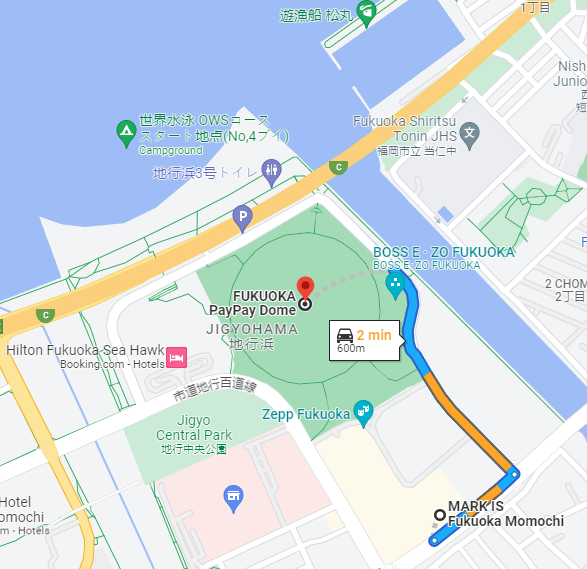

A 2018 story in Travel Weekly Asia trumped a new building in Japan’s sixth-largest city and the second-largest port city after Yokohama: “A new mega mall parks in Fukuoka’s waterfront area.”

Placing the words “mall” and “park” so close together so it almost reads “mallpark” already translates well into English.

But here, parking a mall seemed to be the best way to describe what was happening, even if there was no ballpark attached. Then again, this Mark IS mall is a two-minute walk from the city’s Fukuoka PayPay Dome, a 40,000 seat facility with a retractable roof built in 1993 and, with a diameter of 216 meters, is called the “world’s largest geodesic dome.” It is home of the Fukuoa SoftBank Hawks, part of the Nippon Professional Baseball’s Pacific League since the late 1930s.

You can look it up: More to ponder

== A Friedman interview (above) with “Good Seats Still Available” podcast host Tim Hanlon is promoted as such: ” University of Maryland physical cultural studies professor Michael Friedman cozies up to the pod machine this week for a thinking man’s look into the evolution of the grand old American ballpark – and a provocative thesis of how designers of this generation of baseball stadiums are embracing theme park and shopping mall design to prioritize commerce and consumption over the game played inside them.”

== Friedman offered a brief Q&A from his publisher’s website that included this insight:

Q: How do you wish you could change your field?

A: Too much of the conversation surrounding stadiums focuses on economic questions – what stadiums do for cities – rather than discussing what stadiums mean for cities. Besides the economic answer being very clear in so far as economists have found little to no positive fiscal impact, there is much less discussion about how sports impact the quality of urban life. While it may be difficult to justify a half-billion dollar expenditure on the basis of a stadium making the city a better place to live, that would be a much more legitimate policy debate than those discussed on purely economic grounds. This shift would also open up conversations about how to make stadium into more inclusive spaces and how best to use stadiums to serve the public interest.

== From New York Journal of Books on “Game of Edges”: “Schoenfeld offers an insightful look at the world of sports gambling. He pays particular attention to such phenomena as Draft Kings and the new comfort that professional sports has found in their partnerships with gambling. He points out the symbiotic relationships that exist with the data boom, the wireless phone, and media explosion that began with ESPN and has developed well beyond with the advent of streaming. The emerging revenue streams generated from all these sources seem endless. Business organization and practices are examined. Emerging from an age when professional sports franchises thought all that was needed was to open the doors and the fans would pour in, the emphasis now is on marketing, customer relations, and community relations. The exploitation of markets and the creation of new streams of revenue are key parts of the business model in professional sports.“

== “America’s Classic Ballparks: Celebrating Parks Past and Present,” by James Buckley (Becker&Mayer Books, 208 pages, $24.99) came out in September, 2022 focusing on nostalgia generated by nine ballparks, including Dodger Stadium, Wrigley Field, the original Yankee Stadium, Fenway Park, Ebbets Field, Tiger Stadium, the Polo Grounds. It then throws in, now quite curiously, Oriole Park at Camden Yards, and Oracle Park, which we weren’t even sure what park that was until we realized it’s the latest bastardization of the San Francisco Giants’ Pacific Bell/Pac Bell Park (2000-03), SBC Park (’04-’04) and AT&T Park (’06-’18) at 24 Willie Mays Plaza and was once also home to the Kraft Fight Hunger Bowl of college football (2002-’13), the XFL’s San Francisco Demons (2001), the UFL’s California Redwoods (2009), and Cal’s football team in 2011.

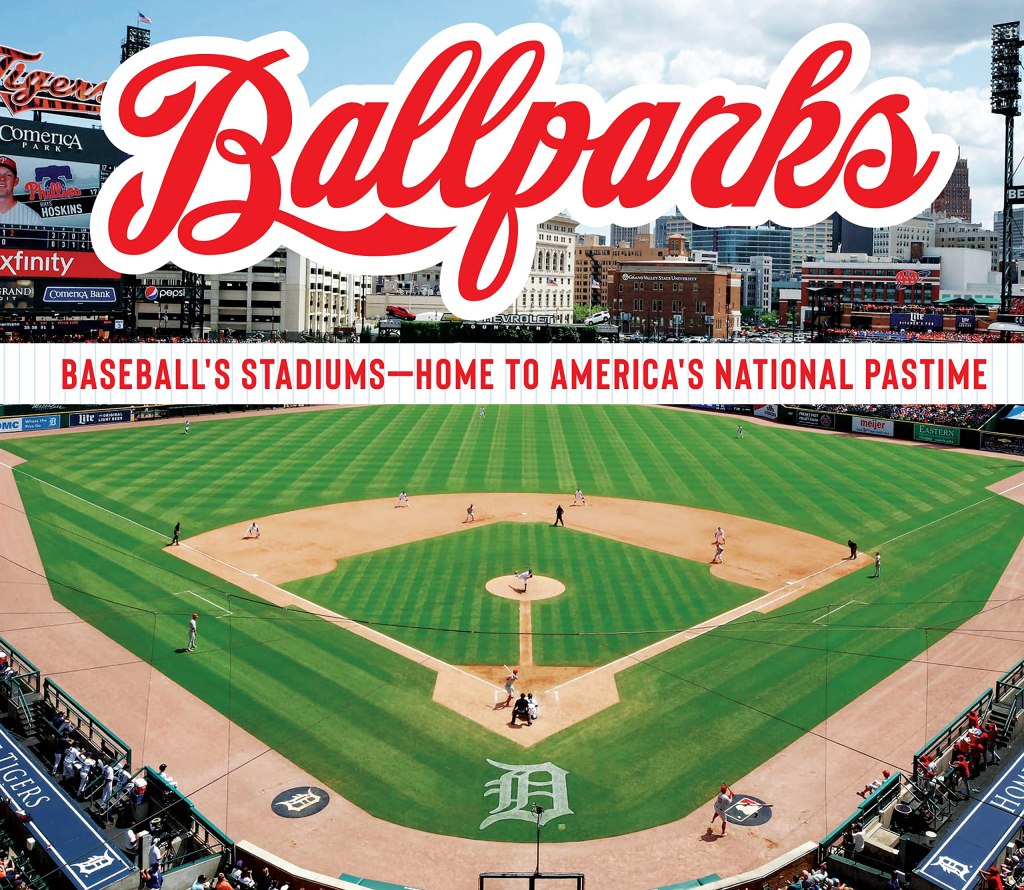

This is in addition to “Ballparks: Baseball’s Stadiums – Home to America’s National Pastime” from Publications International Ltd. (issued Sept. 2022, 144 pages, $19.98), which coverage all 30 MLB parks. In 2019, we caught up with “Ballparks Then and Now,” by Eric Enders (Pavilion Books, 160 pages, $22.50), which seemed to be an extension of his own 2018 book called “Ballparks: A Journey Through the Fields of the Past, Present and Future” (Cantwell Books, 304 pages, $26.99)

1 thought on “Day 27 of 2023 baseball books: Hey, mallrat, scurring around in the cathedrals of commerce … who moved your cheese?”