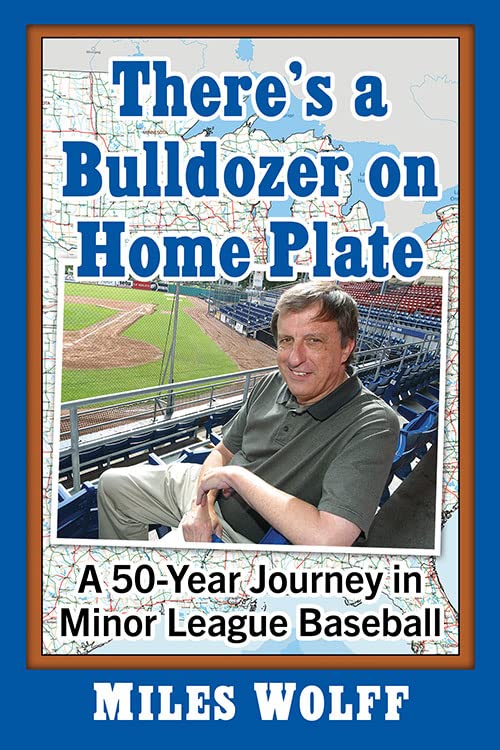

“There’s a Bulldozer on Home Plate:

A 50-Year Journey in Minor League Baseball”

The author:

Miles Wolff

The publishing info:

McFarland

185 pages; $29.95

Released February 10, 2023

The links:

The publishers website

At Bookshop.org

At Powells.com

At Vromans.com

At TheLastBookStoreLA

At Skylight Books

At Diesel Books

At BarnesAndNoble.com

At Amazon.com

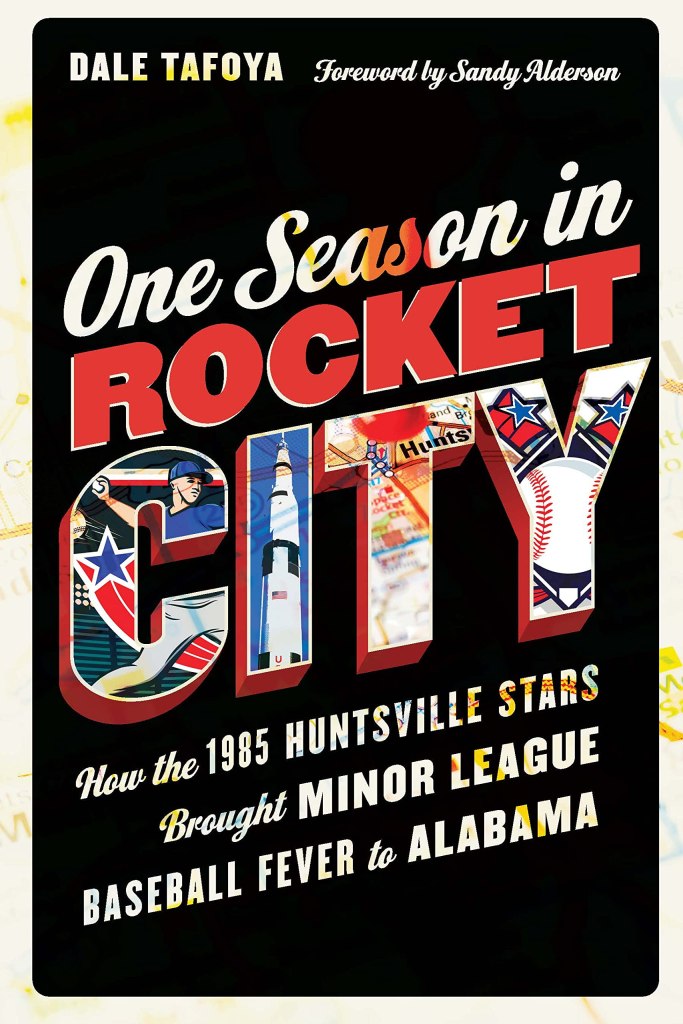

“One Season in Rocket City:

How the 1985 Huntsville Stars Brought

Minor League Baseball Fever to Alabama”

The author:

Dale Tafoya

The publishing info:

University of Nebraska Press

224 pages; $29.95

Released April 1, 2023

The links:

The publishers website

At Bookshop.org

At Powells.com

At Vromans.com

At TheLastBookStoreLA

At Skylight Books

At Diesel Books

At BarnesAndNoble.com

At Amazon.com

“Bush League, Big City:

The Brooklyn Cyclones, Staten Island Yankees

and the New York-Penn League”

The author:

Michael Sokolow

The publishing info:

State University of New York Press

316 pages; $29.95

Released April 1, 2023

The links:

The publishers website

At Bookshop.org

At Powells.com

At Vromans.com

At TheLastBookStoreLA

At Skylight Books

At Diesel Books

At BarnesAndNoble.com

At Amazon.com

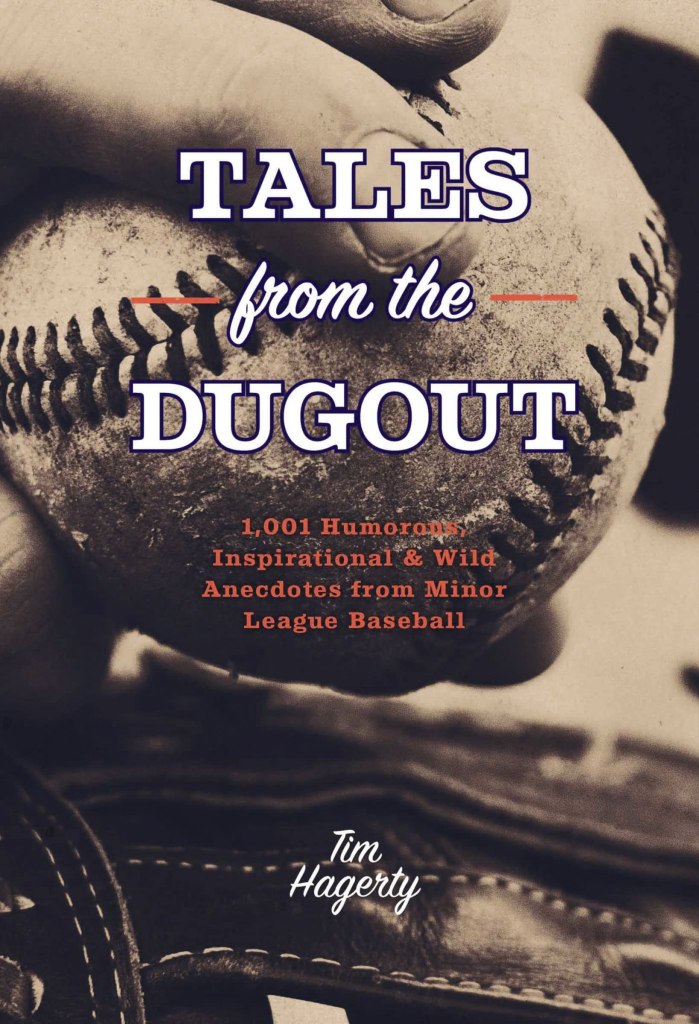

“Tales from the Dugout:

1,001 Humorous, Inspirational and

Wild Anecdotes from Minor League Baseball”

The author:

Tim Hagerty

The publishing info:

Cider Mill Press

368 pages, $16.95

Released March 28, 2023

The links:

The publishers website

The authors website

At Bookshop.org

At Powells.com

At Vromans.com

At TheLastBookStoreLA

At Skylight Books

At Diesel Books

At BarnesAndNoble.com

At Amazon.com

The reviews in 90 feet or less

We’ve been on the lookout for the fourth edition of “The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball: A Complete Record of Teams, Leagues and Seasons, 1876-2019” by Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff. It was set to come out last November. But that didn’t happen.

At last check, it was forecast for an arrival in October with a $99 sticker price and a new publisher.

The book’s online synopsis: “When the pandemic hit in early 2020, baseball’s minor leagues cancelled their seasons. A few independent leagues tried abbreviated schedules, but all Major League affiliates shut down — for the first time in more than 120 years. Since then, Major League Baseball has taken over governance of the minors, and leagues and teams have been eliminated. In its fourth and final edition, this book gives a complete accounting of the minor leagues as they were known from the late 19th century through 2019.”

That smells like a multi-layer obituary.

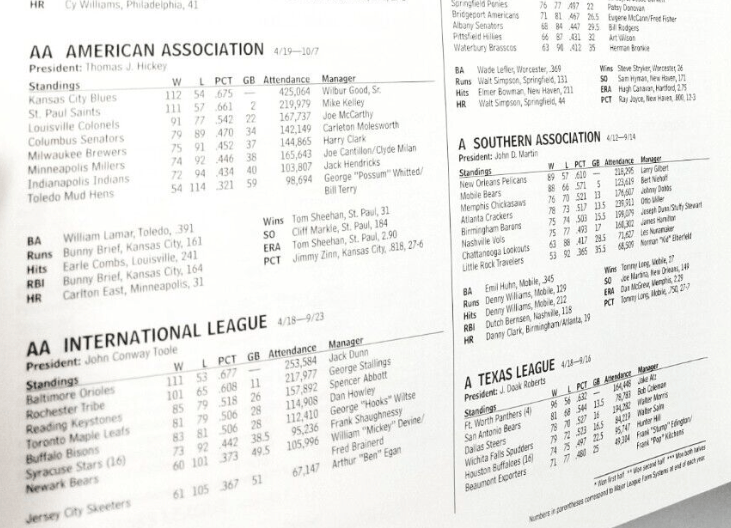

When Johnson and Wolff got the inspiration and gumption to produce the book in 1993 – 24 years after the landmark “The Baseball Encyclopedia” reference book gave us the “complete and official record of Major League Baseball” — it was 420 pages strong, weighing in at three pounds, and published by Baseball America. Wolff was the company’s publisher.

It was given the Macmillan-SABR Baseball Research Award, and worthy of updates in 1997 (672 pages) and 2007 (767 pages), by then, each of them exceeding the initial six-pound delivery of that first edition of “The Baseball Encyclopedia.”

McFarland, the publisher set to release this fourth edition, says on its website that The Sporting News once called the project “wonderful” and “indespendible,” the later of which we will dispense and take it to mean “indispensable.”

The project came from two legendary figures in the baseball media business.

Johnson, a Syracuse grad who became the Society of American Baseball Research’s president and executive director, also put in time as a researcher for the Baseball Hall of Fame. He then became the founder and first director of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. He became the author/editor of the 1994 “The Minor League Register,” which is still available, published by Baseball America. He also edited “The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History,” in 2001. Twenty years after that, in 2021, he also wrote an LGBT contemporary novel, “The Freed Church Boy.”

As for Miles Wolff …

He’s in the leadoff spot for this roundup of new works related to the life and times of minor-league baseball:

In “There’s a Bulldozer on Home Plate,” Wolff collects his notes, memories and concerns to look back at his involvement in a sport that seems supernatural.

First, some context.

Back in 2004, MLB historian John Thorn and Alan Schwarz, authors of “Total Baseball,” did a list of the 100 most important people in baseball history. Wolff came in at No. 79 – ahead of some of the more recognizable Ken Griffey Jr., Bob Feller, Harry Caray, Scott Boras, Roger Kahn, Carl Hubbell and Mel Allen.

Thorn and Schwarz wrote it up this way:

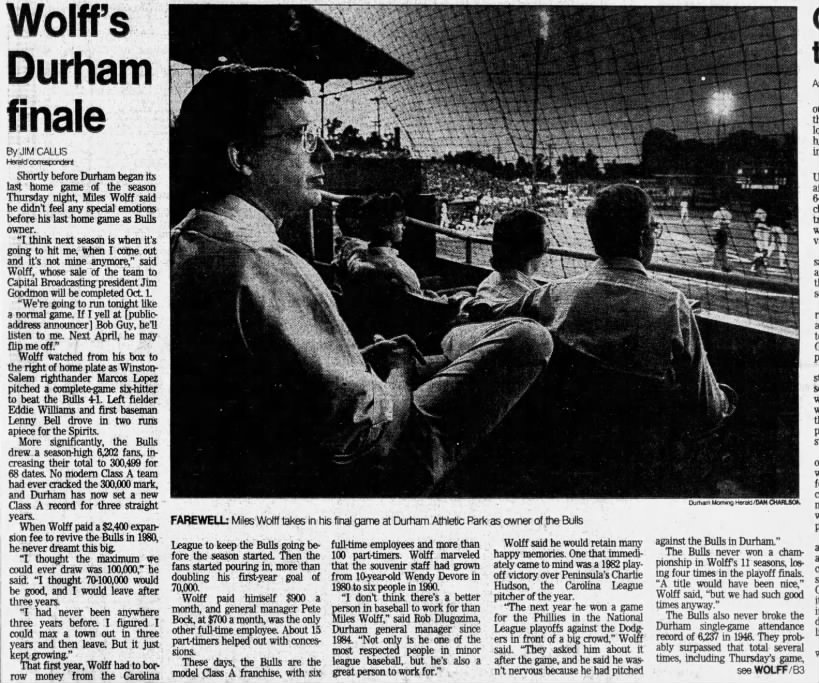

More than anyone, Miles Wolff is responsible for the modern renaissance of minor-league baseball, as it emerged from the lean years of the 1960s and ’70s to the boom of the 1980s and ’90s. Wolff bought the Carolina League’s Durham Bulls for just $2,666 in 1979, nurtured it into a local success, and owned the franchise as it became a national symbol of the minor leagues after the release of the film Bull Durham in 1988. He sold the team in 1990 for $4 million just as the minors began to flourish again.

A baseball purist at heart, Wolff grew frustrated at the money – and marketing-driven approach exhibited by the regular minor leagues, whose clubs were beholden to the major-league organizations to which they fed players. (Communities rarely got to know the best players, because they were promoted to the next level within three or sixth months.) So in 1993, Wolff re-established the Northern League, a circuit in the upper Midwest made up of teams that operated outside the sphere of Organized Baseball. The Northern League’s six clubs signed players — often minor-league veterans on their way down or overlooked collegians — to stock their rosters. The Northern League was an instant success and spawned imitators across the country.

Wolff’s first baseball job came in 1971 as the general manager of the Double-A Savannah (Georgia) Braves, and he subsequently was a GM in Anderson, South Carolina., and Jacksonville, Florida. Wolff also owned Baseball America, the Durham-based magazine of the minor leagues, for most of its lifetime. He bought the magazine from founder Allan Simpson in 1982 and served as president and publisher until selling the company in 2000.

Here and now, Wolff provides a lot of the dirty details.

Many of his stories are pulled from what he already chronicled in the Bulls Illustrated newsletters in the 1980s. There he tapped into his relationships with people like Tommie Aaron (Henry’s brother), managers Clint “Scrap Iron” Courtney and “Dirty” Al Gallagher, Mike Veeck (son of Bill Veeck, and a legendary team owner himself in St. Paul, Minn.), plus a young screenwriter named Ron Shelton who embedded himself with Wolff’s Bulls in North Carolina to find the narrative he could create for his Kevin Costner-led movie, “Bull Durham.”

For what it’s worth, Wolff says he actually paid just $2,417 for the Bulls’ franchise fee. But he then needed another $30,000 for operating expenses.

“I had never owned a business before and knew nothing about operations,” he writes. “I was a history major (at Johns Hopkins University) which was not coming in handy. I quickly found a book store and purchased a Cliffs Notes on business.”

One of his investors, Thom Mount, had ties to Universal Pictures and MCA records and once told him: “Some day we will make a movie here.” Wolff never believed it.

We get to see how Wolff’s love of the game comes across in a passage like this on page 36:

“Baseball is a game for the senses. One can hear the crack of the bat, the cheers of the crowd … the eyes see the green grass, the streaming rays of light from the towers spilling on the field … On entering the stadium, the smell of popcorn and hot dogs brings memories … Each ballpark has its own unique smell. In Durham, when tobacco was a dying king, the fresh sweet smell of tobacco leaves spilled over the stadium. In Amarillo, the stockyards provide an odor that, while not always pleasing, informed spectators that Amarillo was a western cattle town. And in Richmond, one could smell cookies being baked. It was a grand odor. A cookie factory was near Parker Field and it made for one of the most delightful ballpark smells imaginable.”

Wolff predictably laments in the epilogue how the minor leagues have been somewhat kicked to the curb, a change sped up by the pandemic when the MLB took it all over and lopped off more than three dozen teams, leaving 120 to be under its control – four for each of the 30 MLB teams, one at each level of Triple-A, Double-A, High-A and Single-A. It also meant Triple-A would be the 20-team International League and 10-team Pacific Coast League, known as Triple-A East and Triple-A West, and dissolving the American Association.

“The minors were now run by a gaggle of lawyers in New York City,” Wolff writes about the changes. “It was not pretty. … I do not trust MLB nor do I believe it has the best interests of baseball in its sights. One of the most worrisome aspects of MLB taking over the minors is that no one in the offices in New York has ever worked in the minors. There is no love, no passion, no knowledge of the bush leagues. No one in the office knows or appreciates the history and traditions.”

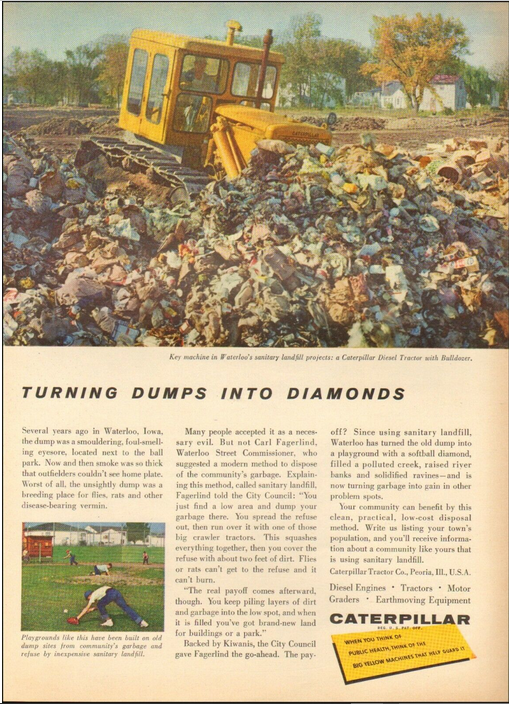

Like, how the book got its title.

Wolff explains it came from a 2009 conversation “between a league president and commissioner” (he doesn’t identify if he was either, but you get a sense he was). There was a chance that the Northern League team in Nashua would have to abandon hopes of playing its last week of home games at its stadium because the city, which owned the facility, wasn’t happy about the team’s ownership defaulting on a rent check. The city decided it was prudent to park a bulldozer on home plate, let the mayor have the keys, and see what might happen.

“Is it a big bulldozer?” the commissioner asks.

“Really big,” says the league president.

In “One Season in Rocket City,” Dale Tafoya taps into his Oakland Athletics’ history knowledge – following his books “Billy Ball: Billy Martin and the Resurrection of the Oakland A’s” in 2020, and especially “Bash Brothers: A Legacy Subpoenaed” in 2008 – by chronicling how the franchise’s Double A affiliate in Nashville needed a new home base in 1984.

A’s executive Walt Jocketty helped Nashville Sounds owner Larry Schmittou jockey for position with other cities and somehow land in Huntsville, Ala., also known as “Rocket City” because of its aerospace industry.

They ran off with the Southern League title in 1985 in a newly built 10,000-seat stadium, led the league in attendance, and had a roster filled with the young players who would eventually be the foundation of the franchise’s World Series teams later that decade – including 20-year-old Jose Canseco (the league’s MVP with 25 homers, 80 RBIs and a .318 average in 58 games before jumping to the big leagues that September), Tim Belcher (11-10, 4.69 ERA), Terry Steinbach, Eric Plunk, Luis Polonia and Stan Javier.

The Huntsville Stars had it going on – but mostly with players who didn’t turn out to be stars, such as Rob Nelson (32 homers, 98 RBIs, 137 strike outs in 140 games), Rocky Coyle (who inspired the team’s booster club to give out an award in his name to those who best demonstrated his hustle, spirit and love of the game), Tom Zmudosky, Ray Thoma, Chip Conklin, Wayne Giddings and John Marquardt. Their stories keep the book moving.

The city was without a team for five years until the Angels’ double-A affiliate known as the Rocket City Trash Pandas landed in 2020, with a new stadium luring them in. The Stars stuck around in Huntsville for 30 years (the A’s kept them until 1998 before transferring their allegiance to Midland, Tex., allowing the Braves to come in from ’99 to 2014) before they relocated to Biloxi, Miss., and became known as the Shuckers.

Ah, shucks.

In “Bush League, Big City,” Michael Sokolow admits the 2020 MLB contraction mess, along with the COVID shutdown, allowed him to tie together years of previous research on how and why two minor-league teams, the Brooklyn Cyclones and Staten Island Yankees, gravitated to relocating in New York during the late 1990s with very mixed results.

It also does a deep dive into the existence of the New York-Penn League, a Single-A short season operation that began in June after the MLB draft and lasted until September. It had been the oldest and longest running in the minor-league system since its debut with six teams in 1939 (as the Pennsylvania-Ontario-New York League, shortened to PONY League) but then saw its final season end up crowning its final champion in 2019 – the Cyclones – as one of the NYPL’s14 teams spread over eight states.

With the NYPL gone, the Cyclones (with two others) moved to the new High-A East, one went independent, two joined a college league and four others moved into the new MLB Draft League to showcase players prior to the annual draft.

The Staten Island Yankees, aka the “Baby Bombers,” folded in 2020, and once had the late Mike Gillespie, who played for and managed USC to a College World Series, as its manager in 2007, losing to the Cylones in the playoffs.

Sokolow, an associate professor of history at Kingsborough Community College for City University of New York (CUNY) who got a degree in economics and American Studies from Brooklyn College and then a masters and PhD from Boston University in American and New England Studies, explains how he had most of the history of the league and its two New York teams documented by 2010, but wasn’t compelled to finish it. The MLB stepping in to take things over pushed him over the edge.

The takeaway, as explained in the introduction, is how “professional baseball exists at the intersection of cultural nostalgia and the business of sports. The inherent tensions between these two qualities suffuse the history of the sport, locally and national marketing campaigns and the loyalty that fans and communities feel about toward their teams. This has been especially true in the borough of Brooklyn and at Steeplechase Park in Coney Island where the Cyclones team makes its home. It proved to be less impactful in Staten Island, where the lack of a nostalgic past combined with many challenging real-world limitations ultimate doomed a once-promising franchise.”

It again shows how the game at this level can be a toxic combination of power, limitations, dreams, geography and the idea that Rudy Giuliani once had a magic touch in the city.

Sokolow also shows how both the Cyclones (property of the Mets) and Yankees (branded by the big-league team) were riding a wave of post-“Bull Durham” minor-league magic established in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, crediting Miles Wolff with his Durham Bulls as a shining example of what might happen with an investment and a dream. The NYPL, with just its three-month schedule of 70-some games, had an attendance of 300,000 in 1981 and by the end of the decade it had more than doubled. But there-in lies the lesson covered in Chapter 4: “New Stadiums Do Not Produce Economic Growth.”

In “Tales from the Dugout,” Tim Hagerty draws from his experience as a broadcaster for the Triple-A El Paso Chihuahuas since 2004 (the San Diego Padres’ top affiliate), writing for publications such as Baseball Digest, MLB.com, The Sporting News and The Hardball Times, and also cranking out the 2012 book, “Root for the Home Team: Minor League Baseball’s Most Off-The-Wall Names and the Stories Behind Them.”

The result is a tracking down all sorts of Ripley’s-type stuff that happened on the pre-MLB level, whether you want to believe it or not.

One thing we couldn’t really believe: Across the back cover of this fun-fact-finding mission is a description of this as a ” Compendium of Minor League Shenanigans.” All things considered, that would have made a better book title on the front than something that just kind of sits there generically and has been recycled many times in the baseball book business.

Among the tidbits we enjoyed biting into as they actually pertained to the teams and people chronicled above:

Page 359: “The Double-A Rocket City Trash Pandas … is a slang term for a raccoon.”

Page 170: “In the early 1990s at Huntsville, Alabama’s Joe Davis Stadium, a Double-A pitcher flinched because of a close lightning bolt and was called for a balk.”

Page 307: “Sandy the Seagull (is the name) of the High-A Brooklyn Cyclones’ mascot, who’s named after Brooklyn, N.Y., native and former Brooklyn Dodgers pitcher Sandy Koufax.”

(On page 202 of “Bush League, Big City,” Sokolov points out how Mets owner Fred Wilpon “sensed the value of the Coney Island angle from the outset and made sure not to squander the marketing opportunities it afforded them … The Cyclones’ crowd-pleasing mascot was Sandy the Seagull, a friendly version of the ubiquitous birds so familiar to beachgoers.” Sokolov doesn’t mention the mascot’s namesake – or that Wilpon and Koufax as good friends).

Page 301: The New York Penn League’s Staten Island Yankees wore Staten Island Pizza Rats uniforms for select games in 2018. The Pizza Rats’ name as a nod to a viral video of a rat dragging a full slice of pizza down the steps of a New York subway station. Staten Island’s affiliate, the New York Yankees, were reportedly upset about the pinstripes pizza plan.”

Page 44: “The Class B Miami Beach Flamingos gave manager Pepper Martin a bulldozer as a reward for his winning season in 1954. Martin used it on his off-season ranch in Oklahoma.”

It always comes back to feeling like you’re being bulldozed. By a Durham Bull.

How they go in the scorebook

No minor miracle that the MiLB remains alive today.

Two more things to ponder:

There was just the story recently about how the city of Durham, N.C., is trying to come to terms with a new MLB edict that requires minor-leaguet eams to “meet higher standards for their facilities.” Which could mean the city has to kick in more than $10 million to get Durham Bulls Athletic Park up to code by 2025 or they could be left behind.

“I just want to be clear, the Bulls ain’t going nowhere,” Mayor Pro-Tem Mark-Anthony Middleton said at the 2022 meeting. “When people come to those Bulls games, it drives so much other economic activity.”

The Bulls are also offering to pay $1 million toward the required upgrades and another $1 million to additional upgrades. MLB is not offering to pay anything.

The place needs multiple batting cages, women’s locker rooms, larger clubhouses for both teams, office renovations and more storage. The ballpark was built in 1995 when the team was playing at the Single-A level. The new stricter standards for Triple-A stadiums also add costs. The Bulls are owned by Capitol Broadcasting Company, parent of WRAL-TV and WRALSportsfan.com.

It makes dollars. It makes sense.

There was also a piece, in 2019, from FiveThirtyEight.com asking the question: “Do We Even Need Minor League Baseball?” At the time, there were 245 min0r league teams, the most since 1948, double what there was in 1979. The Houston Astros started a trend to downsize their affiliates in 2017 and consolidate resources. There seemed to also be a trend of blue-chip projected players being rushed through the minors anyway to see what they could do on the big-league level. No time for development, apparently, since the data showed only 17.6 percent of drafted and signed players even make the big leagues, and more than half of those won’t ever produce better than a 0.1 career WAR. It’s a circular argument again based on how much money and time you want to invest and nurture a player.

“MLB’s approach to the minor leagues is ripe for change in part because of how much data can be collected off the field these days,” writes Travis Sawchik.

Most MLB front offices don’t seem to have that kind of patience any more.

This should have been the red flag that change was coming, and COVID just exacerbated it.

Books like these remind us of what they once did, and who was there to make sure they stayed important.

They can remain valuable petri dish platforms for the ultimate business model of the MLB. But the intrinsic value is to their communities that have supported them and felt compelled to add them to their identity.

Minor league baseball doesn’t need to deal with any more identity theft.

You can look it up: More to ponder

== Give more extra credit to Miles Wolff for having authored a charming murder mystery novel, “Season of the Owl,” back in the early 1980s.

It is a coming of age story about a 14-year-old boy, Tom, in North Carolina and a minor league club, the Centerfield Owls, hit by racial protests in the 1950s South. One reviewer on GoodReads.com: “An obscure but entertaining baseball story centered around a murder, with clues revealed chapter by chapter. Wolff does a nice job of setting the story in small-town North Carolina in the late days of segregation. The rinky-dink minor league operation is presented in great detail, as you might expect from someone who has made his living in minor league baseball. I finished it in three nights, staying up late the last night to get through it and see how it ended.”

== Following up on Miles Wolff and Bull Durham, there’s the 2012 novel, “The Greatest Show on Dirt,” by James Bailey. Here’s more on that also from our friend, Ron Kaplan.

== Michael Sokolow connects with the podcast “Good Seats Still Available” here.

== More on baseball in Huntsville can be gathered from a new book by Mark McCarter, strategically titled “Baseball in Huntsville” (The History Press, 112 pages, $23.99, released June 5, 2023). McCarter covered baseball for the Huntsville Times for 17 years.

== One last minor insult added to injury: It was announced on July 31 that MLB has finally paid $185 million to settle a lawsuit filed in 2014 by members of the California League and extended spring training or instructional leagues in Arizona in the 2009-2011 range. They claimed violations of the federal Fair Labor Standards Act. As a result, some 24,000 players will receive a payment of about $5,000 for their troubles.

1 thought on “Day 28 of 2023 baseball books: Sweating the minor stuff”