This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 19:

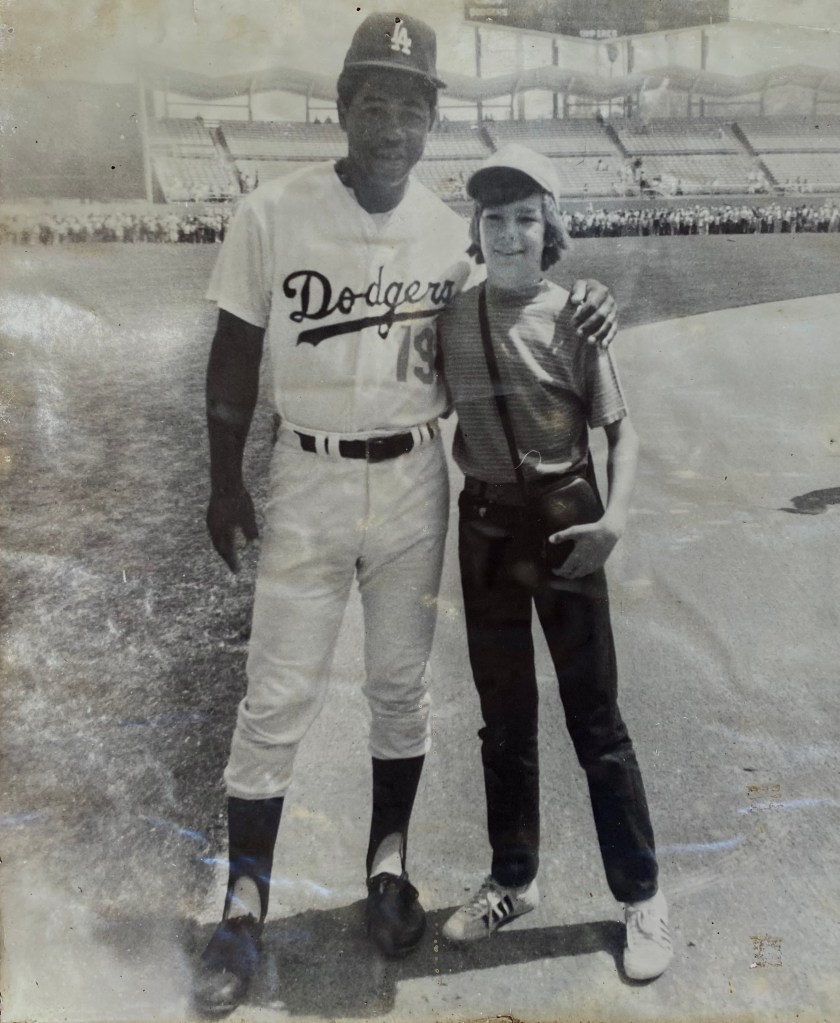

= Jim Gilliam: Los Angeles Dodgers

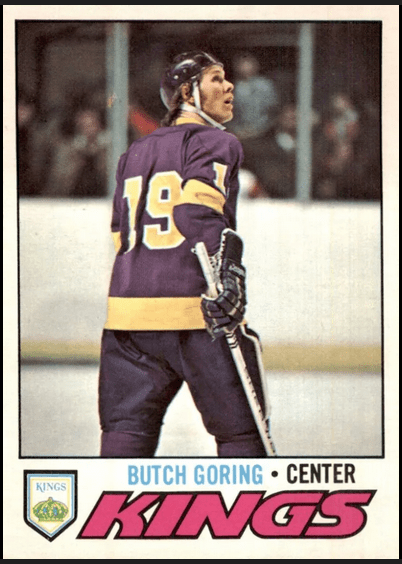

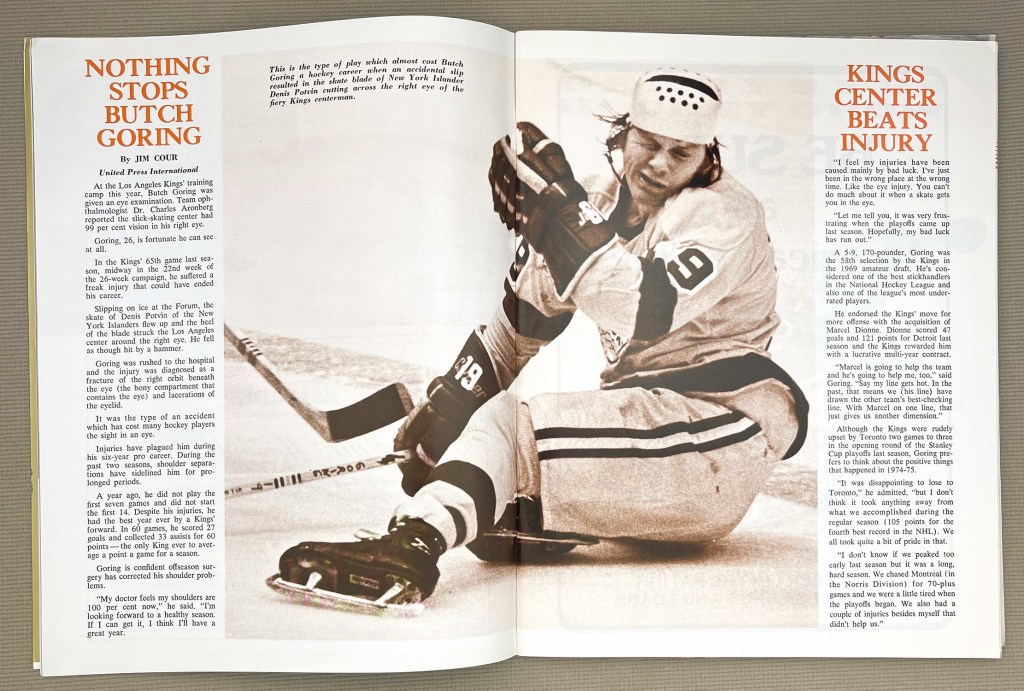

= Butch Goring: Los Angeles Kings

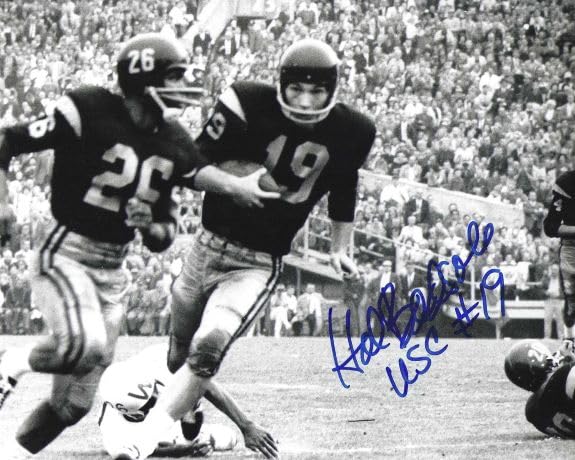

= Hal Bedsole: USC football

= Fred Lynn: California Angels

= Marco Danelo: USC football

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 19:

= Mike Gillespie: USC baseball

= Jim Fox: Los Angeles Kings

= Dennis Dummit, UCLA football

= Lantz Rentzel: Los Angeles Rams

= Will Ferrell: Los Angeles Dodgers, Los Angeles Angels

The most interesting story for No. 19:

Louis Lapp: El Segundo Little League pitcher/first baseman (2023)

Southern California map pinpoints:

El Segundo

Louis Lappe, at 6-foot-1 and 153 pounds, already stood head-and-shoulders above most of his El Segundo All Star teammates when they took a trip to Williamsport, Pennsylvania, during a summer vacation that focused in winning game after game in the Little League World Series tournament.

Fact is, the 12-year-old could make level eye contact with the team’s 53-year-old volunteer manager, Danny Boehle.

In one magical moment, No. 19 appeared to leap maybe 19 feet or more in the air before taking a title home with him.

On a Sunday afternoon before a national TV audience, many of whom were crammed into local restaurants in Southern California to see what might happen, Lappe took his victory lap around the bases capped off by jumping high in the air and landing on home plate at Howard J. Lamade Stadium to punctuate a game-winning home run in the 2021 Little League World Series championship game.

A 6-5 victory happened after, just an inning earlier, the contest was tied by a grand-slam gut punch delivered by the kids from Willemstad, Curacao, a team from a small island off the coast of Venezuela home to just 150,000 residents. Instead, Curacao endured its second straight title loss and third in previous last four tournaments.

Lappe’s home run was the first and only Willemstad allowed in its six World Series games.

“I was just looking for a good pitch,” Lappe told ABC after his Series-leading fifth home run in seven games. “My mentality was just get the next guy up and if we kept doing that, we would have won either way, but I’ll take the homer. When that pitch came, even before I hit it, I was like, ‘Oh!’ I was so excited and happy. When I got around to home plate, I made sure to touch it.”

Lappe’s teammates had already nicknamed him “The Natural.” Just 24 hours earlier, in the U.S. title game, Lappe hit a three-run homer in the fifth inning and struck out 10 batters in 5 1/3 innings on the mound for a 6-1 triumph against Needville, Texas. It was the fourth day in a row El Segundo won an elimination game — the same Needville sent it into the consolation bracket earlier in the week.

Lappe nearly didn’t show up for his final year of Little League eligibility. He played for a few years before, but sat out the season at age 11, deciding instead to focus on soccer, basketball and another travel baseball team. Lappe eventually asked Boehle if he would be OK to rejoin the program.

Boehle said he was fully on board – enough to want to coach the team himself.

The background

El Segundo won 20 out of 22 games in five local, state and regional tournaments in the summer of ’21. Its only other loss, aside from the first-round in Williamsport, was to the all-star team from Sherman Oaks, 4-3, in the opening game of the championship series in what would decide the Southern California State Tournament. El Segundo won the rematch, 3-2, later that day.

When the Little League World Series started Aug. 17 in Pennsylvania, several players were afflicted with a stomach virus and had to sit out. Or was it just a case of the nerves? That didn’t seem to be part of their vocabulary.

Boehle, tearing up before the TV cameras moments after Lappe’s championship-game homer, hugged by his own son, Quinn, also a member of the team, and said: “Now I can get emotional. We finally made it. That was our mission, to do it with my son and all these boys. … What we did may never happen again in the history of El Segundo.”

Players then scooped up dirt from the infield into paper cups to take home as a souvenir.

Of Lappe’s 10 hits in El Segundo’s seven games of the World Series, five were home runs. He also had 10 RBIs and scored eight runs. Teammate Brody Brooks, 3-for-3 with a homer in the U.S. title game, had 13 hits, 13 runs scored and five RBIs. In the title game, Brooks, the last of four El Segundo pitchers, was credited with the victory, pitching a hitless sixth inning, striking out two. The rest of the squad: Lennon Salazar, Finley Green, Lucas Keldorf, Colby Lee, Max Baker, Declan McRoberts, Ollie Parks, Crew O’Connor and Jaxon Kalish. All with the cool baseball names, right?

“These guys know what they’re doing and they believe in the coaches,” Boehle said. “We believe in them. It’s just the attitude and the personalities they’ve chosen over the years that has kept us so connected.”

Lappe later told a reporter he “knew the ball was gone before he hit it.” Really? “It’s hard to describe because it’s so unique feeling like you’re left standing on a cloud or something.”

A crowd of El Segundo residents scattered about on blankets and lawn chairs chanting “Go ‘Gundo” at George Brett Field as they watched the Sunday title game on a large-screen TV some 2,600 miles away. Victory celebration plans quickly followed.

The El Segundo players and coaches were not only celebrated with a city-wide parade, but visits to Dodger Stadium and a USC football game were part of it, while the players were about to return to school and perhaps some normalcy.

“After weeks of celebrations, many of the players appeared to be a bit beleaguered with yet another parade, but Louis stood with a grin from ear to ear and waved to the exuberant fans who lined the streets of El Segundo,” a story reported in South Bay magazine.”

El Segundo is a Spanish word that translates to “The Second” in English. It is a reference to the second Chevron oil refinery, which helped create the town decades earlier. As Normar Garciaparra said when the team joined the Dodgers’ SportsNet LA pregame show: “It’s not El Segundo any more. It’s El Primero. They’re not second to anyone. Time to change the name.”

Even Daily Variety was taking claim of the kids as “Hollywood’s hometown Little League team.”

The context

Since El Segundo Little League launched in 1954, no team from that baseball-enriched town had ever gone so deep in a tournament. There are plenty of high school titles to boast about at El Segundo High, especially when John Stephenson was the coach and future big-league careers were shaped there.

The El Segundo Little League field is named after George Brett, the Kansas City Royals’ Hall of Fame third baseman and youngest of four Brett brothers who played at El Segundo High. George was the second, after his brother Kemer, to make it to the big leagues.

In a 2025 piece by USA Today marking the top five moments in Little League history since its 1947 conception, Lappe’s title-winning homer ranks No. 3.

Sean Burroughs’ two-year-run with the Little League teams from Long Beach in 1992 and ’93 came in No. 1.

Long Beach was the U.S. champion in ’92, but lost to Zamboanga City in the Philippines in the international title game. However, when that squad was found to have over-age and non-eligible players, it was forced to forfeit the title to Long Beach.

A year later, the Long Beach team pushed its way back to Williamsport through all the qualifying, won the U.S. title again, and this time defeated a squad from Panama in the International final, 3-2. Burroughs threw no-hitters in both his team’s pool-play opener against Ohio on August 23 and then in the U.S. Championship game on August 26.

Long Beach is one of only three teams to repeat as world champs. Sean Burroughs, the son of former American League MVP Jeff Burroughs, had a 10-year run in the Major Leagues a decade later and even tried to make a comeback with the Dodgers’ farm system some 25 years after that moment in Williamsport.

Huntington Beach (2011, a 2-1 win over Japan) and Granada Hills (1963, a 2-1 win over Stratford, Conn.) are the other two Southern California teams who have won Little League titles. Irvine (1987), Northridge (1994), South Mission Viejo (1997) and Thousand Oaks (2004) also made it to the title game before coming up short. Chula Vista, near San Diego, won it all in 2009 and lost the 2013 international title game.

Little League in Southern California is rich in history. The Wrigley Little League in L.A. sits on the site of the old Wrigley Field, just East of the Coliseum. Many who play on that dirt and grass don’t even know of its connection to that time and place.

Long before Mone Davis, Southern California Little League history has the story of Victoria Brucker, No. 20 for the West Team, the first girl on an American squad in the World Series, representing San Pedro’s Eastview Little League in the summer of 1989. Their cleanup hitter as a 5-foot, 3-inch, 137-pound first baseman. Getting all the way to the U.S. semifinal game. Girls had only been playing Little League for 15 years prior to that moment. She is now a swimming coach in Hawaii.

As for famous athletes who have a connection to Little League in Southern California:

= Hall of Fame pitcher Jim Palmer, who grew up playing in the Beverly Hills American Little League. He moved to Whittier from New York when his widowed mother went to operate a dress shop. They moved to Beverly Hills in 1956. “We first lived at 145 S. Almont, then after my mother got remarried, my stepfather bought a house in Coldwater Canyon,” Palmer said. “But I kept going to Horace Mann (Elementary School) because I wanted to stay in school with my friends. They’d come to games driven by their chauffeurs, while I came on my bike after my paper route.”

= Dusty Baker, who managed the Houston Astros to the 2022 World Series, grew up playing Little League in Riverside. It led to a 19-year MLB career (12 with the Dodgers, and the 1981 World Series) and 20 years as a manager. In 2007, he was added to the Little League Hall of Excellence.

= Matt Cassel was part of the ’94 “Earthquake Kids” from Northridge that won the U.S. bracket and lost to Venezuela 4-3 in the final. During his football career at USC, where he was a backup to Carson Palmer and Matt Leinart, Cassel was drafted by the Oakland Athletics in 2004, but he signed with the New England Patriots as a seventh-round draft pick in ’05 to back up Tom Brady. With Kansas City, Cassel made the Pro Bowl and retired after the 2018 season.

= Brian Sipe, who would have an NFL MVP season as a quarterback in Cleveland and retire as the franchise leader in passing yards and TDs, was part of the Northern Little League in El Cajon/La Mesa team that ran through the Little League World Series, winning a pair of games in extra innings before defeating Texas in the final to claim the championship.

= Actors Kevin Costner and Tom Selleck were added to the Little League Hall of Excellence. Coster, inducted in 2000, was recognized for his participation in Saticoy Little League in Ventura — where he once struck out 16 batters in a game and threw a couple no-hitters. Selleck, inducted in 1991, was an all-star pitcher with the Pioneer Little League of Sherman Oaks.

= Current MLB players with a connection to their local Little League includes Gerrit Cole (Western Little League in Tustin), Giancarlo Stanton (Tujuga Little League), Lucas Giolito (Santa Monica Little League), Nolan Arenado and Matt Chapman (Lake Forest Little League), Jack Flaherty (Southern Little League in Sherman Oaks), Christian Yelich (Thousand Oaks Little League), Nick Pratto (on the Huntington Beach Little League team that went to the Little League World Series in 2009), Hagen Danner (Ocean View Little League of Huntington Beach that went to the 2011 Little League World Series), Max Fried, Gabe Kapler and Torey Lovullo (Encino Little League), Pete Crow-Armstrong (Southern Little League in Sherman Oaks), Noah Davis (Huntington Valley Little League in Huntington Beach), Freddie Freeman (Long Beach Little League), Austin Barnes (Magnolia Little League in Riverside), Jeff McNeil (Goleta Valley South Little League in Santa Barbara), Michael Lorenzen (East Anaheim Little League), Kyle Higashioka (Seaview Little League and Walnut Creek Little League in Huntington Beach), Lars Nootbaar (El Segundo Little League) and Stephen Strasburg (Santee American Little League)

The legacy

Lappe has a biographic page on the PerfectGame.com website listing him at 6-foot-1 and 165 pounds, noting he will be in the Class of 2029. His FB Velo (speed of his fastball) was last registered at 75 mph in May of 2023, with a bar chart about how it has progressed from 55 mph in March of 2021.

By February of 2026, Lappe, who grew to 6-foot-2 as a 15-year-old freshman third baseman, started his high school career at Harvard-Westlake School in Studio City. Manager Danny Boehle and four of Lappe’s El Segundo Little League teammates went to rival Loyola High in L.A.

Meanwhile, the El Segundo Little League website continues to tally up the national coverage it has received since that summer of fun.

Who else wore N0. 19 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

Jim Gilliam, Los Angeles Dodgers infielder (1958 to 1966), Los Angeles Dodgers coach (1964 to 1978):

Best known: His number was retired by the franchise shortly before the 1978 World Series, a reflection of how much the organization appreciated his loyalty and ability to play nearly any positions — mostly second base, third base or left field — going back to his 1953 season in Brooklyn as the NL Rookie of the Year. Starting with the Baltimore Elite Giants of the Negro Leagues as a teenager, Gilliam came arrived five years after Jackie Robinson’s 1947 debut, and he stayed as a player through the 1966 World Series. During the Dodgers’ 1963 World Series run, Gilliam hit .282, with 77 runs, 60 walks and 19 stolen bases to place sixth in the NL MVP voting. While an active player in 1964, he started coaching first base, one of the first Blacks to do so. He started all seven games of the 1965 World Series against Minnesota having started the year as a retired player. His key defensive play of Game 7 perserved Sandy Koufax’s 2–0 shutout victory that won the World Series for the Dodgers. A four-time NL All-Star, Gilliam is the only Dodgers player other than Sandy Koufax to earn four World Series title rings (’55, ’59, ’63, ’65).

Not well remembered: In his 2025 book, “Jim Gilliam: The Forgotten Dodger” author Steve Dimore makes a case that surmises that Gilliam could have not only been the Dodgers’ first Black manager but the first in MLB history if the openings fell in his favor. It would have been most appropriate considering his connection with Robinson.

He was given the nickname Junior as a 16-year-old member of the Negro League’s Elite Giants, coming up in 1946, but also had the nickname “Devil” because of his pool hall prowess.

Butch Goring, Los Angeles Kings center (1969-70 to 1979-80):

Best known: After the 1977-78 season, Goring was the first NHL player to win the Lady Byng Trophy — the player who “exhibited the best type of sportsmanship and gentlemanly conduct combined with a high standard of playing ability” — and the Masterson Trophy — the player “who best exemplifies the qualities of perseverance, sportsmanship, and dedication to ice hockey.” His most famous moment on the ice for the Kings was in the 1975-76 playoff quarterfinal series against Boston, as he scored the overtime game-winning goals in Games 2 and 6.

Goring scored 30 or more goals four straight seasons and had 20 or more goals in nine seasons for the Kings. On March 1, 1975, Goring had a four-goal game in a win over Minnesota. He had a career-best 87 points (36 goals, 51 assists) in 1978-79. His only All-Star game appearance came the next season in 1979-80 — just months before he was traded to the New York Islanders in exchange for defenseman Dave Lewis and right winger Billy Harris. At the time, Goring, who just turned 30, was the Kings’ franchise leader in goals (275), assists (384) and points (659) in the 736 games he played over 11 seasons. “I guess I’m disappointed that it didn’t work out Hollywood-style,” Goring said at the time of his trade. “When I thought about my career, I always had it in my mind that I hoped to play it out for the Kings.” Said Kings star center Marcel Dionne: “Butch was a sparkplug for us. I’ve seen him score some of the most spectacular goals that you can think of.

With the Islanders, Goring became part of four Stanley Cup championship teams in six seasons, as he flipped his No. 19 to No. 91, which the Islanders would retire. Upon leaving Los Angeles, Goring’s No. 19 was given to …

Jim Fox, Los Angeles Kings right winger (1980-81 to 1989 -90):

Best known: Fox’s 10-year career as a player saw him score 30 goals three times and retire in the Top 10 list of most all franchise offensive categories. From there, Fox became almost better as the team’s TV game analyst, including a 27-year run with Bob Miller that had the team’s 2012 and 2014 Stanley Cup title runs.

Not well remembered: Fox didn’t play during the 1988-89 season as he recovered from knee surgery. When he returned for 11 games of the ’89-90 season, he wore No. 4 because he had relinquished his No. 19 jersey to …

Larry Robinson, Los Angeles Kings defenseman (1989-90 to 1991-92):

Best known: The Kings acquired the eventual Hockey Hall of Fame defenseman from Montreal after his 17 seasons and six Stanley Cup wins there. Nicknamed “Big Bird” for his 6-foot-4 and 225-pound frame, Robinson’s three seasons in L.A. was capped off by an All-Star game selection at age 40. Robinson’s name appears on the Stanley Cup 10 times: Six as a player, three as a coach or assistant coach and once as a scout. The Kings hired him as their head coach in 1995 after he was with the New Jersey Devils. His four-year term: 122-161-45, making the playoffs once. Perhaps his most impactful move was opening a Play It Again Sports shop in Torrance.

Hal Bedsole, USC football receiver (1961 to 1963):

Best known: “Prince Hal” went from Reseda High to Pierce Junior College and into the USC Athletic Hall of Fame, the National Football Foundation Hall of Fame and inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame just prior to his death in December of 2017. The 6-foot-5, 230-pound Bedsole helped lead the Trojans to a 1962 national title, the first for John McKay, catching two touchdowns passes in USC’s win over Wisconsin in the 1963 Rose Bowl. The two-time first-team All AAWU and the first Trojan to have 200 receiving yards in a single game (201 against Cal in 1962, a school record for 21 years). He caught 82 passes for 1,717 yards and 20 touchdowns in his Trojan career, all school records at the time, and his 20.9 career average per reception remains a USC record (minimum 30 catches).

Not well remembered: Bedsole, the 1959 L.A. City Player of the Year, came to USC as a quarterback.

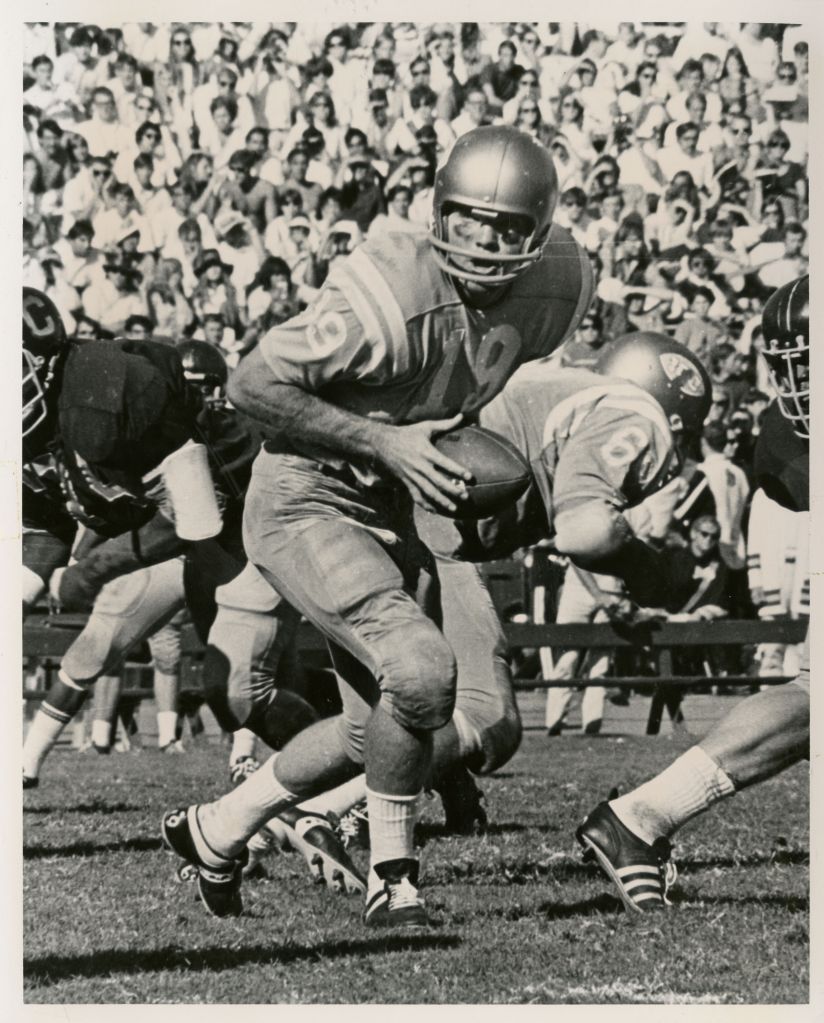

Dennis Dummit, UCLA football quarterback (1969 to 1970):

Best known: The Long Beach Wilson high grad spent two years at Long Beach City College and then set 14 records with the Bruins in 21 Pac-8 games, finishing as the top passer in the program’s history and two-time winner of the Red Sanders Award as the team’s MVP. At the time of his UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame induction in 2004, he was ranked as the No. 7 Bruin all-time passer with 289 completions out of 552 passes for 4,356 yards and 29 TDs. A National Football Foundation Scholar Athlete, Dummit was passed over in the NFL draft after his senior year, signed as a free agent with the Los Angeles Rams and played in a few exhibition games before going to the Canadian Football League and World Football League.

Not well remembered: From Dan Jenkins’ profile on Dummit for Sports Illustrated in late October of 1969 focused on the influx of JC transfers into the major college system: “First of all, nobody wanted Dummit when he got out of high school in Long Beach. Everybody wanted the guy who played ahead of him, a thrower named Bob Gritch (sic). UCLA signed Gritch (sic). But so did the Baltimore Orioles, and they paid him money…. Dummit, meanwhile, was talked to by Utah, Navy and Long Beach State and offered nothing. So he went to the community college … A good-looking, yellow-blond 6-footer, who wears a sweatband around his head to make his headgear fit, Dennis developed in the Jaycees as a passer, a cool, accurate thrower with what (UCLA coach Tom) Prothro calls “the best anticipation” of any passer he’s coached. Last December, Prothro knew he wanted Dummit — needed Dummit — and he got him. “We had to find a quarterback, and I went to the Jaycees to get one,” said Prothro. “I’m happy I found one with a 3.6 grade average as well as an arm.”

After Dummit led UCLA to a 6-0 start and a No. 6 national ranking, they suffered a 14-12 loss to USC. As Jenkins wrote for SI on Dec. 1: “All afternoon and evening the Wild Bunch bounced Dennis Dummit around the Coliseum floor like a double dribble, smothering him for loss after loss and forcing him to throw the football upward, downward and sideways.”

Fred Lynn, California Angels outfielder (1982 to 1984):

Best known: The El Monte High star turned down the chance to sign with the New York Yankees in 1970 and went to USC — to play wide receiver on the Trojans’ football team, part of the roster that won the 1972 Rose Bowl. An All-American on the baseball team, Lynn was drafted by Boston in 1973 and, two years later, was the American League Rookie of the Year and AL MVP. Coming to the Angels in an ’81 pre-season trade where he was swapped for Joe Rudi and Frank Tanana, Lynn made three more straight AL All-Star appearances (to give him nine in a row), highlighted by hitting a grand slam in the 1983 game at Comiskey Park in Chicago.

Not well remembered: With the Angels, Lynn initially wore No. 8 in 1981 because Bert Campaneris had the No. 19 that Lynn wore in Boston.

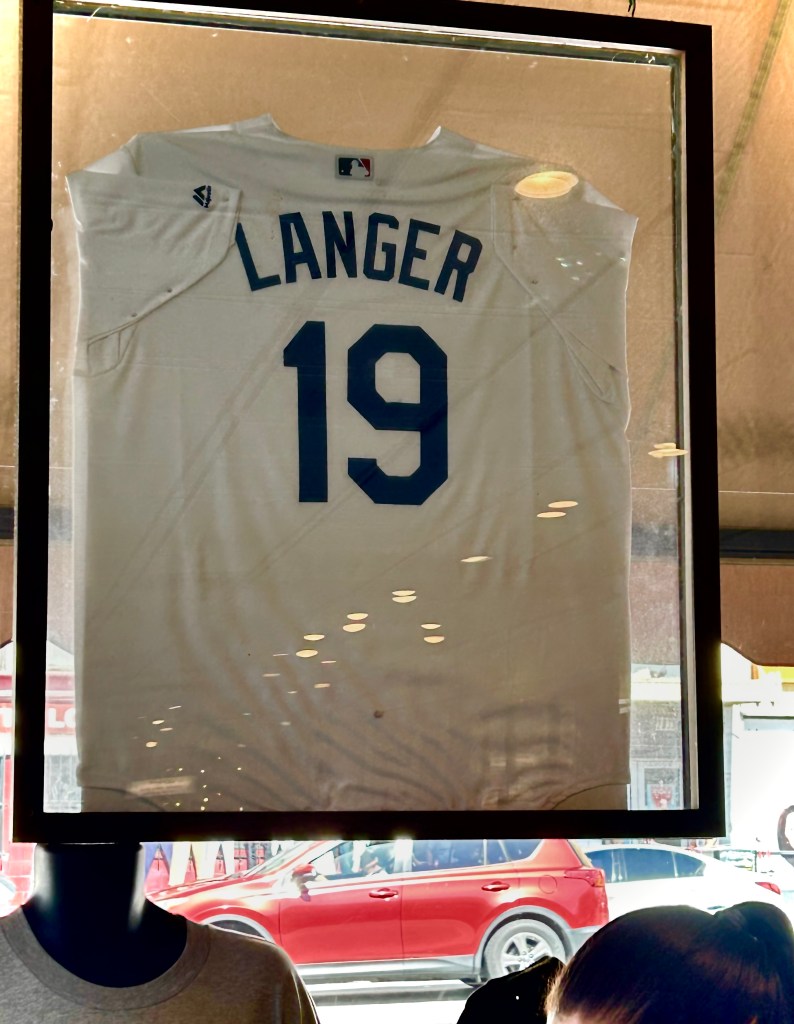

Mike Gillsepie, USC baseball coach (1987 to 2006):

Best known: One of only two to play in and coach an NCAA championship baseball team, Gillespie came from Hawthorne High to play on USC’s 1961 NCAA title team, and then coached the Trojans to five Pac-10 titles and four College World Series appearances, winning it all in 1998 after going to the championship game in 1995. Gillespie, who won 763 games at USC and coached 42 All-Americans, was also successful as UC Irvine’s head baseball coach from 2008 to 2018. He was inducted into the American Baseball Coaches Association Hall of Fame in 2010 , the USC Athletics Hall of Fame in 2018 and had his No. 19 retired in 2022 and posted with a logo on the right-field fence next to Rod Dedeaux’s No. 1.

Bob Boyd, USC basketball center (1950-51 to 1951-52):

Best known: An All-CIF player at Alhambra High School, the 6-foot-6 center became more high-profile as the Trojans head basketball coach who won 215 games from 1966 to 1979 but was in only one NCAA Tournament because of conference rules. Boyd was USC’s most valuable player as a senior in 1952, averaging a team-best 12.2 points a game that season for Forest Twogood’s 16-14 team. Boyd also led Twogood’s ’50-51 team with 9.2 points a game

Marcedes Lewis, UCLA football tight end (2002 to 2006):

Best known: Out of Long Beach Poly, named to the Parade magazine high school All-American team, Lewis was the first Bruin to win the Mackey Award as the nation’s tight end after making 58 receptions for 741 yards and 10 touchdown as a senior. In 32 stars of 49 games, Lewis, at 6-foot-6 and 261 pounds, set the UCLA school record for tight ends with 126 receptions as well as 1,571 yards and 21 TDs. The 28th overall pick in the 2006 NFL Draft by Jacksonville was inducted into the UCLA Athletics Hall of Fame in 2022.

Have you heard this story:

Lamar Willis, Compton College football receiver (2025):

In 2025, the Compton College football program was in danger, again, of being canceled for budget reasons, lack of victories and general disinterest. The community kept rallying to keep it alive. Enough so that it started supplying more players to fill the roster from past generations. Willis, who last played at Bellflower High and was coaching football as late as 2014, was 45 when he was recruited to play — joining his son, Josiah, wearing No. 20 and playing defensive back (out of Cerritos High). Willis’ stats say he played in two games during Compton’s 0-10 season (the last two games were losses by forfeit). This is the same Lamar Willis who ran for mayor of Compton in 2021. Among Willis’ teammates on this Compton team was 50-year-old linebacker Orson Villalobos (his bio is on the No. 50 post).

Mario Danello, USC football kicker (2003 to 2006):

As a sophomore in ’05 and a junior in ’06, the San Pedro native and walk-on to the program made 127 extra points and converted 26 of 28 field goals. Danelo earned a scholarship in the fall of 2005 and won the starting job, and benefitted from the high-powered Trojans offense by setting NCAA, Pac-10 and USC records for PATs (83) and PAT attempts (86). The son of NFL kicker Joe Danello was an All-L.A. City first team linebacker as a senior in 2002. Six days after USC’s win over Michigan in the 2007 Rose Bowl — he connected on two 26-yard field goals and two of four PAT tries — Mario Danello was found dead at the bottom of White Point Cliff in ear the Point Fermin Lighthouse in San Pedro. Two thousand people attended Danelo’s funeral at Mary Star of the Sea Catholic church. For the ’07 season, USC players wore a No. 19 sticker on their helmets. In the 2007 season opener, coach Pete Carroll and Athletic Director Mike Garrett presented a jersey to Danelo’s parents, and after USC’s first touchdown against Idaho, the team lined up for a PAT try without a kicker and took a five-yard delay of game penalty as a tribute.

Curtis Pride, Anaheim/Los Angeles Angels outfielder (2004 to 2006):

He was born deaf. Audiologists found him to be 95 percent deaf in both ears as a result of his mother having rubella – German measles – while she was pregnant. He would play professionally for 23 years, including parts of 11 seasons at the major-league level. A left-handed-hitting outfielder who primarily served in a reserve role, he had 199 big-league base hits, 50 coming off the bench, and 29 as a pinch-hitter. In 1995, Pride was presented the Tony Conigliaro Award to honor a player who has overcome “an obstacle and adversity through the attributes of spirit, determination, and courage” that were trademarks of Conigliaro. In 1997, the Detroit Tigers released him, and the Boston Red Sox (Conigliaro’s former team) picked him up, but gave him only two at-bats. The first resulted in a pinch-hit home run, at Fenway Park. Why Pride didn’t get more opportunities at the highest level – and why he jumped from organization to organization – is somewhat of a mystery. Asked if his deafness played a role, Pride wouldn’t speculate as to whether he was discriminated against. All he’d say was, “Teams appreciated my ability on the field, and more importantly, I was a very good team player.” This, from his Society of American Baseball Research biography.

Lance Rentzel, Los Angeles Rams receiver (1972 to 1974):

No. 19 turned out to be his NFL comeback jersey — the number he wore earlier in his career with Dallas and Minnesota, and then returned for one last year with the Rams after serving a 10-month suspension by the NFL for conduct detrimental to the league. Rentzel was convicted of marijuana possession, but he was already on probation for an indecent exposure charge before a 10-year-old girl that went back to 1970 when he was with the Cowboys. Then it was revealed that in 1966, he was charge of indecent exposure and disorderly conduct. In ’71, Rentzel, given No. 13 and trying to reboot his image, led the Rams in receptions with 38 even as his value as a player had started a steep decline from his previous six NFL seasons. The Cowboys tried to cut their losses, sending him to the Rams as he was undergoing psychiatric help. The subsequent scandal caused his wife, actress and singer Joey Heatherton, to divorce him. While with the Rams, he was the subject of a long 1972 feature story in Sport magazine — “The Story Behind His Fight For Respect” –which led to his autobiography, “When All The Laughter Died in Sorrow.”

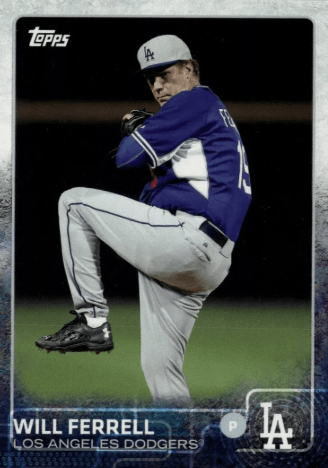

Will Ferrell, Los Angeles Angels outfielder, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2015):

Baseball-Reference.com has official documentation for how the 47-year-old started and ended his day on March 12, 2015 — wearing 10 different uniforms and playing 10 different positions in the Cactus League exhibition action. That included appearances as an Angels center fielder and Dodgers pitcher. He wore No. 19 for every team (but then wore No. 20 for San Diego at the end, knowing No. 19 had been retired for Tony Gwynn). It is likely he’s the only person to wear No. 19 for the Dodgers since it was retired for Gilliam.

Ferrell may have been a former basketball and football player at University High in Irvine — wearing No. 85 as a place kicker — and then went to USC as a sports information major. His sports-related films include playing ABA basketball (“Semi-Pro” in 2008), NASCAR racing (“Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby” in 2006), figure skating (“Blades of Glory” in 2007) and soccer-dad coach (“Kicking & Screaming” in 2005).

Ferrell, who in 2010 made a surprise appearance for the Triple-A min0r-league Round Rock Express as an “angry pitcher” wearing a fake mustache named “Rojo” Johnson who made one pitch and got into a fight, pulled off the feat of playing MLB baseball as it was recorded as an HBO documentary that became a cancer fund-raising exercise. He’s also in line to portay John Madden in a biopic about the former NFL coach and legendary broadcaster.

As the Angels played the Cubs in Tempe, Ferrell subbed in for center fielder Mike Trout in the third inning and actually held the Cubs’ Wellington Castillo to a single on a ball lined to him. Several teams and a helicopter ride later, he caught up with the Dodgers in Peoria as they were playing San Diego. Dodgers manager Don Mattingly called on Ferrell as a relief pitcher in the seventh inning. The Padres’ Rico Noel tried to bunt on him, but Ferrell fielded it and threw him out. Ferrell came out, swapped his jersey for Padres’ garb, and played right field against the Dodgers for an inning. He then retired. Topps also made baseball cards of him to prove it happened.

And …

We also have:

Jeff Dankworth, UCLA football quarterback (1974 to 1976)

Alex Hannum, USC basketball forward (1943, 1946 to 1947)

Remy Hamilton, Los Angeles Avengers kicker (2002 to 2007))

Bert Campaneris, California Angels shortstop (1979 to 1981)

Dante Bichette, California Angels outfielder (1988 to 1990)

Bill Munson, Los Angeles Rams quarterback (1964 to 1967)

Lance Rentzel, Los Angeles Rams receiver (1971 to 1974)

Sean Avery, Los Angeles Kings defenseman (2002 to 2007)

Note: Chargers receiver Lance Alworth did not play for Los Angeles in 1960 but joined the team a year later en route to a Hall of Fame career in San Diego.

Anyone else worth nominating?

2 thoughts on “No. 19: Louis Lappe”