This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 2:

= Tommy Lasorda: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Kawhi Leonard: Los Angeles Clippers

= Derek Fisher: Los Angeles Lakers

= Morley Drury: USC football

= Darryl Henley: UCLA football

= Robert Woods: USC football, Los Angeles Rams

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 2:

= Lonzo Ball: Chino Hills High basketball, UCLA basketball, Los Angeles Lakers

= Gianna Bryant: Mamba Academy basketball

= Leo Durocher: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Adam Kennedy: Anaheim/Los Angeles Angels

= Cobi Jones: UCLA soccer

= Shai Gilgeous-Alexander: Los Angeles Clippers

The most interesting story for No. 2:

Tommy Lasorda: Los Angeles Dodgers manager (1976 to 1996)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Fullerton, Los Angeles (Dodger Stadium)

What’s your opinion of Tommy Lasorda?

Curses. We have quite a few to share.

He motivated and manipulated. He spoke in sound bites as deftly as he could unravel magnificent yarns of stories that seemed to good to be true.

But he always did better with an audience.

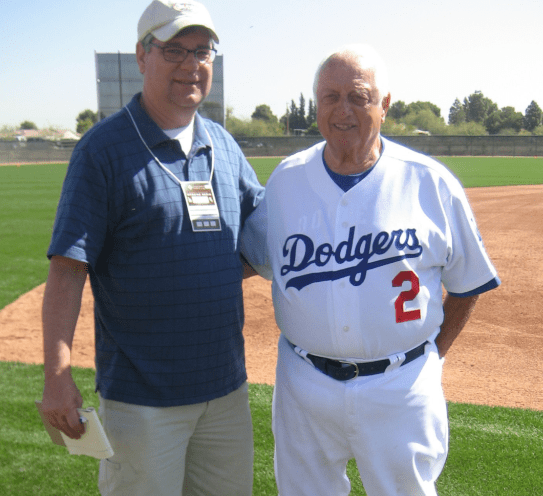

One day, at an event in downtown L.A., Lasorda grabbed me by the left forearm. There was urgency.

“We’re going to Paul’s Kitchen,” he said, leaning in. “You gotta go with us.”’

The invite to go to one of L.A.’s most historic Chinese restaurants seemed to mean — With Lasorda and six friends, you get extra egg rolls.

I couldn’t commit because of a deadline for a story to write. I had to take a Teriyaki rain check.

So, the Pied Piper that he was, Lasorda did the quick exit with and a group in tow, out the door of Sports Museum of L.A. — this was after a 2010 press conference that had to do with where Kirk Gibson’s 1988 Game 1 bat and uniform might end up going — and over to a familiar spot where he could hold court for the rest of the afternoon.

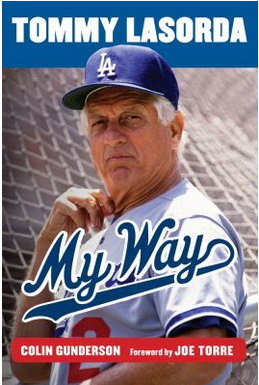

My reschedule, a few years later, became a a rather spectacular three-hour lunch-turned-dinner at the Dodger Stadium dining room prior to a game. The push behind this meeting was a bit less obvious to him. We needed material to compile a pre-written biography/obit on him in the event that he would leave us here for Dodger heaven.

So before a game in 2013, between spurps of split pea soup, a side of cottage cheese, a scoop of tuna and a bowl of fresh peaches – he was watching his diet at age 85 – we otherwise chew the fat on all sorts of subjects.

It was astounding. I had plenty of material now. It would be another eight years before it was even needed, as he went to the “Big Dodger in the Sky” and died in January of 2021 at age 93 at the height of COVID.

This time, it was Angelus News, the Catholic news organization of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, asking if I could compile “the Catholic life of Tommy Lasorda” based on my interactions as well as research.

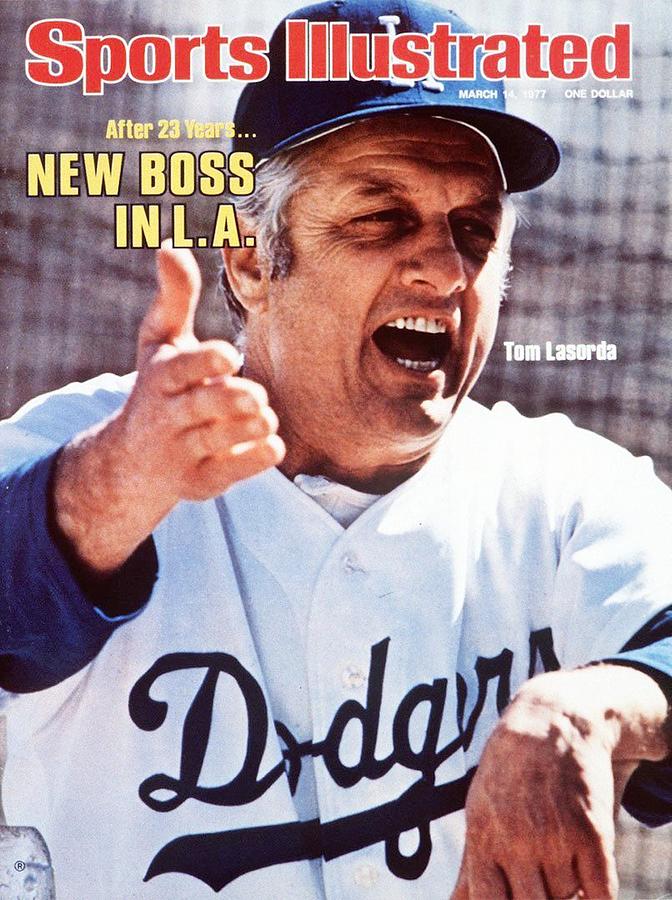

The man who skippered the Dodgers’ last four games of the 1976 season through 76 games of the 1996 season, covering two World Series titles, four NL pennants, eight NL West titles, 48 ejections and one win short of 1,600 in the regular season already admitted his life has been full of blessings, mixed in with plenty of foul words. That was just his rough-and-tough DNA, blaming it on his Italian heritage.

Artfully enunciated, dodging all sorts of backlash.

The model Catholic? There are saints in the church’s hierarchy who have done plenty worse things. It’s all up for interpretation.

If we could define Vin Scully was an Irish Catholic who openly practiced his faith, Lasorda would be far more a cultural Italian Catholic who leaned into his religion’s traditions and history when necessary to make a point. Church attendance was still necessary.

He had an oversized, gold-framed portrait of Mother Teresa on the wall of his cluttered stadium office. It was near a portrait of Roger Mahony, the archdiocese’s Emeritus Cardinal, and one of plenty of controversy in his own time.

Then there is also a picture of an unassuming nun wearing a white habit.

“That’s Sister Immaculata, my seventh-grade teacher,” Lasorda explained in “I Live For This! Baseball’s Last True Believer,” a 2007 biography, one of three books done by and about him. “She was the only one who believed in me.”

Los Angeles was a Lasorda Believer almost from the first time it met him.

This walking contradiction, a complete force of nature, practically willed the Dodgers into winning World Championships in 1981 and 1988, albeit the talent they had was decent, but hardly the best on the field at that time.

So when there were times you the high-regarded, well-built Dodgers of 2022 and ’23 wilt in the first round of the National League playoffs, one couldn’t help but wonder: What Would Lasorda Have Done?

Just follow the timeline.

The storylines

In no particular order, a dozen more Lasorda-related stories that never go out of style in our memory bank:

== The 1988 World Series: Lasorda finds a way to use NBC’s Bob Costas to inspire the underdog Dodgers, also known as “one of the weakest ever (teams) to take the field for a World Series,” captured in the MLB Network documentary “Only In Hollywood” (which we documented ourselves) :

== The 1988 World Series L.A. City Hall celebration: Let’s Dance. (And let’s follow it up with something else years later)

== The Kingman rant and the Bevacqua rant: After the Dodgers absorbed a 10-7 loss to the Chicago Cubs on May 14, 1978, behind three Dave Kingman home runs, Lasorda was asked by radio correspondent Paul Olden: “What is your opinion of Kingman’s performance?” Four years later, on June 30, 1982, Dodgers reliever Tom Niedenfuer hit San Diego Padres batter Joe Lefebvre in the head with an 0-2 pitch after surrendering a home run. Padres player Kurt Bevacqua regarded it as intentional and charged the field. A reporter asked Lasorda about Bevacqua’s accusation. His answers:

== The on-field protest that led to the Dodgers having to forfeit a game after Dodger Stadium fans threw balls onto the field — did Lasorda instigate them?

== The Reggie rant: From the 1978 World Series, when there was no call of interference:

== An episode of ABC’s “Fantasy Island.” The first season. Actor Gary Burghoff plays Richard Delao of Chicago, an accountant who dreams of major-league stardom. Wearing a Dodgers’ No. 37 jersey, the fantasy doesn’t become real until Tommy Lasorda makes it happen (“Smiles, everyone!”) This is likely where the term “Fantasy Camp” became an idea:

== The 2001 MLB All-Star Game tumble: Lasorda is coaching third base for the National League and nearly doesn’t live to tell about it (maybe this led to them wearing helmets?)

== Lasorda claims he discovered a great young broadcaster named Al Michaels as he was managing the Dodgers’ Triple-A team during a series in Hawaii:

== The time when Lasorda went bare-chested and swam laps in the LA Police Academy pool to amuse David Letterman on “Late Night”:

== The Hall of Fame speech, which includes the story of how Lasorda claims he snuffed out Cincinnati Reds manager John McNamara’s candle in the church:

The numerology

When Tommy Lasorda came up as a pitcher for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1954, he had No. 29. He switched to No. 27 later that season, as well as through four games in ’55. Somehow, there are photos of him wearing No. 21.

With the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League in 1957, coming to Southern California a year before the Dodgers, he wore … we aren’t sure. Still checking. Maybe he had it torn off him during a game where he instigated one of the most famous L.A. baseball brawls in history.

(There’s another great story to research: The time in 1948 with the Phillies’ Schenectady Blue Jays of the Canadian-American League when he struck out 25 batters pitching all 15-innings, then drove in the winning run)

As a manager in the Dodgers farm system with Triple A Spokane (1969 to ’71) and Albuquerque (1972), he wore No. 11.

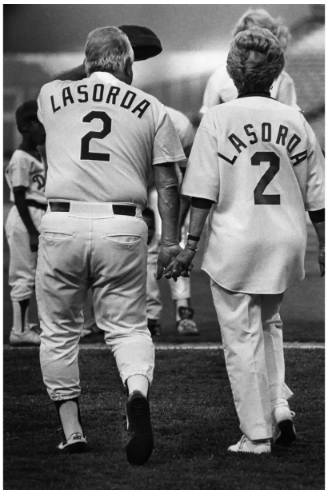

In four seasons as the third-base coach for Walter Alston, Lasorda from 1973 to ’76, wore No. 52. He changed to No. 2 for the 1977, his first full year as the Dodgers manager. (He was named to the position in September of ’76, but No. 2 was still being worn by backup catcher Ellie Rodriguez).

After Lasorda took No. 2, he kept that for the next 19 seasons, seeing it retired by the Dodgers for him. Not anyone else. Even though Lasorda said it was a way to honor Leo Durocher, who wore it as a Brooklyn Dodgers shortstop for six seasons spread out between 1938 to 1945, some of which overlapped with his time as a player/manager from 1939 (picked over Babe Ruth) to ’46 (skipping the ’47 season of Jackie Robinson because of a suspension) and coming back in ’48.

Durocher, too, was also a coach for Walter Alston’s Los Angeles Dodgers from 1961 to ’64 — often playing himself in various TV shows — which kept him in the public eye between the time he managed the New York Giants (1948 to ’55) and then both the Chicago Cubs (’66 to ’72) and Houston Astros (’72 to ’73). It led to a Hall of Fame induction in 1994 based on winning more than 2,000 games over 24 years with his “combative, swashbuckling style,” according to the words on his Cooperstown plaque.

(When Ken Gurnick put together a list of the Best Dodgers Players by Uniform Number, he gave Durocher the number 2 based on the fact he was a two-time All-Star NL shortstop wearing at the end of his playing career — which began with the 1929 New York Yankees, wearing No. 7).

There is also the fact that a players who was one of the closest to Lasorda, shortstop Bobby Valentine, wore it for the Dodgers from 1969 to ’72, having come up to the team at age 19 while still at USC.

Durocher, who guided Brooklyn in 1941 to its first pennant in 20 years. was posthumously elected to the Hall of Fame in 1994, his plaque at Cooperstown depicted “Leo the Lip” in a Brooklyn cap. But the Dodgers didn’t retire Durocher’s number as Lasorda was still wearing it. Lasorda’s uniform No. 2 was retired in August of 1997, a month after he was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame as a manager as well.

So No. 2 is all Lasorda.

The mystique

For writer Joe Posnanski’s latest project, “The 50 Most Famous Baseball Players of The Last 50 Years,” he notes goes off script and picks a manager, Lasorda, No. 48 on his list, and notes that the guy had nine NL Rookie of the Year Award winners on his team during his 21 seasons. How could that be?

“Was there some sort of magic that Tommy Lasorda created as manager of the Dodgers, something that inspired young and raw players to step in and start playing at a high level? Lasorda never seemed to me an especially dynamic strategic manager. On the field, he was a pretty bland, old-school, set-lineup guy, stay-with-the-starter guy, bunt-’em-over guy. argue-with-the-umpire guy.

“What Lasorda did as well as anyone—hell, probably better than anyone—was create this mystique about his team. Lasorda’s Dodgers were different than any other team because he said so. Lasorda’s Dodgers were more of a family because he said so. Lasorda’s Dodgers were glamorous because he said so—and he kept bringing around Frank Sinatra and Don Rickles to emphasize the point.

“It does feel like baseball teams used to have outsized personalities in a way that’s missing today. I suppose that comes down to managers having outsized personalities in those days. Lasorda probably took that to the greatest degree. He was a showman as much as a manager. He was all hearts and hugs and rah-rahs and rage and expletives.

“In his last game as manager (in 1996), the Dodgers trailed Houston 4-1 going into the bottom of the ninth. They faced Billy Wagner, and Mike Blowers hit a home run. Then, after a single and a typically ordered Lasorda bunt, Greg Gagne singled in the tying run. In the ninth, Mike Piazza —Lasorda’s hand-picked superstar — hit a long, walk-off home run. Lasorda never wanted the ride to end. But if it had to end, that was the right way for it to end.”

The legacy

There’s at least one way to toast Lasorda into perpetuity.

Or, at least, while Costco has a good sale going.

The discount warehouse store had an display of wine bottles on display bore the bold blue No. 2 in a white circle. It was unmistakable Lasorda.

A company called Lasorda Family Wines

had been around awhile, and Lasorda himself used to make public appearances promoting it. The project was spearheaded by his nephew, David, who found a wine maker in Paso Robles to produce a Cabernet Sauvignon and a Chardonnay that seem to pair nicely with a lot of things, selling in the $25 range.

No Two-Buck-Chuck strategy for No. 2.

Lasorda apparently was introduced to wine making by his father, Sabatino, an Italian immigrant from the small town of Tollo in the Abruzzo wine region. Tommy would “often help his father procure and press grapes before distributing the finished wine to family, friends, and neighbors,” it says on the website.

“We embody Tommy’s fearless spirit and passion in our wine making, and in doing so, seek to honor and preserve his legacy as baseball’s true ambassador.”

Cheers. Two times.

Who else wore No. 2 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

Kawhi Leonard, Los Angeles Clippers forward: (2019-20 to present):

Best known: One of the league’s most influential offensive and defensive player, Leoanrd’s four All Star appearances in L.A. so far surpass the two that the 6-foot-7, 225-pounder had in San Antonio and one with Toronto when he led the Raptors to an NBA title — wearing No. 2 at every NBA stop. The L.A. born Leonard, a standout at Martin Luther King High in Riverside where he averaged 22.6 points and 13.1 rebounds a game as a senior, found a pathway through San Diego State (where his No. 15 is retired) to become the 15th overall pick by Indiana, then traded to San Antonio. He was NBA Finals MVP in 2014 as a 22-year-old. A three-year, $103 million contract as a free agent with the Clippers in 2019 brought him back to Southern California, and seemed to make an immediate impact when he scored 35 points with 12 rebounds in the Clippers’ 111-106 win over the Lakers on Christmas Day. He extended his Clippers deal in January of 2024 with a three-year, $153 million contract — and posted a triple double (25 points, 11 rebounds, 10 assists) in an 11-point win over the Lakers two weeks later.

Not well known: His first name was something his father invented. He wanted something that sounded Hawaiian, like Kauai, one of the Hawaiian islands.

Shai Gilgeous-Alexander, Los Angeles Clippers guard (2018-19):

Best known: Kawhi Leonard had No. 2 available to him upon his arrival in L.A. because Gilgeous-Alexander, the Clippers’ All-NBA Rookie guard for just one season, had been shipped to OKC in exchange for Paul George. The quick fix didn’t pay off. In six seasons as a member of the Thunder, Shaivonte Aician Gilgeous-Alexander, aka SGA, has been an NBA regular-season MVP and scoring champion (’24-’25), two-time All-NBA and three-time All Star, plus a star player for Team Canada in the 2024 Summer Olympics. The Clippers traded for him on 2018 Draft Day (after Charlotte made him the 11th overall pick), giving up a player (Miles Bridges), a 2020 second-round pick and a 2021 second-round pick. In the July 2019 trade, the Clippers send SGA with Danilio Gallinari and five first-round draft picks, and the rights to swap two other first-round picks, in exchange for George, who hung around for five seasons and about $200 million (covering 263 games, an average of about 50 per year) and took a free-agent trip to Philadelphia. On December 22, 2019, Gilgeous-Alexander scored a then career-high 32 points with five assists, three rebounds, and two steals in a 118–112 win over the Clippers. On December 18, 2021, Gilgeous-Alexander scored 18 points and made a game-winning three-pointer at the buzzer to lift the Thunder over the Clippers, 104–103. On November 11, 2024, Gilgeous-Alexander scored a then-career-high 45 points, along with three rebounds, nine assists, five steals and two blocks in a 134–128 win over the Clippers. All while wearing No. 2 for OKC.

Derek Fisher, Los Angeles Lakers guard (1996-97 to 2003-04; 2007-08 to 2011-12):

Best known: The number he’s best linked to is 0.4, for his ability to catch, turn and shoot a buzzer beater to win Game 5 of the 2004 Western Conference semifinals against defending champion San Antonio (final score: 74-73). He played in more than 1,000 games for the Lakers (915 regular season, 193 post season) and was part of five title teams. He ended up as the head coach of the WNBA Los Angeles Sparks from 2019 to 2022, and then at Crespi High in Encino in 2023.

Adam Kennedy, Anaheim Angels/Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim second baseman (2000 to 2006):

Best known: The former North High of Riverside and Cal State Northridge star will be remember for his three-homer game in the decisive Game 5 of the 2002 ALCS against Minnesota, making him the series MVP. He ended up hitting seven homers that post-season after just four total in the regular season. Also wore No. 3 in his final pro season (2012 with the Dodgers).

Cobi Jones, UCLA soccer (1988 to 1991): A 2002 UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame inductee, Jones was a walk-on out of Westlake High and earned a scholarship as he moved into the starting line-up midway through his freshman year and started all four seasons. Team offensive MVP in ’89 and ’91, he helped the team to a 1990 NCAA Championship, was twice named first-team All-Far West (1990, 1991) and as a senior set a record with 18 assists. He finished UCLA with 23 goals and 37 assists.

Robert Woods, Serra High of Gardena receiver (2007 to 2009), USC football receiver (2010 to 2012), Los Angeles Rams receiver (2018 to 2021):

Best known: After wearing No. 2 as a star at Serra High in Gardena and at USC, Woods was finally able to go with No. 2 while with the Rams when the NFL changed its rules in 2021 about allowing single-digits jerseys for receivers. “Just being number 2 my whole life, always was the deuce – ‘the deuce is loose’,” said Woods at the time. “Got to jump on that opportunity to wear the 2 in the hometown. It’s a must.”

Woods, who also wore No. 13 at USC in 2010, initially wore No. 17 for the Rams from 2018 to 2020 when he came back to Southern California.

In high school, Woods was the 2008 Daily Breeze Football Player of the Year when he had 1,378 receiving yards on 81 receptions during a junior season that ended in a CIF Southern Section title game loss to Oaks Christian. Woods added seven interceptions as a defensive back and had six touchdown returns on kicks and punts. As a senior in 2009, Woods caught 66 passes for 1,112 yards, had five carries for 70 yards, and had 96 total tackles along with eight interceptions and a forced fumble on as his team won the CIF Northwestern Division Championship over Oaks Christian and the CIF Division III state title to finish 15-0. Woods also added three individual CIF-SS titles – in the 200 (21.43), the 400 (47.31) and in the 400 relay (41.21) to help Serra claim the Division IV team title.

In three years at USC, Woods caught what remains a school-record 252 passes over 38 games for 2,930 yards (seventh-best all time) and 32 touchdowns (second-best all time). He also ran 14 times for 142 yards.

With the Rams, Woods signed a five-year, $34 million contract in 2017 and finished his first with 56 receptions for a career-high 781 yards and five touchdowns in 12 games. The next year: 86 receptions for 1,219 yards and six touchdowns in 16 games, plus five receptions for 70 yards in a Super Bowl loss to New England. In 2019: 90 receptions for 1,134 yards and two touchdowns. Signing a four-year, $65 million contract extension with the Rams in 2020, Woods finished the season with 90 receptions for 936 yards and six touchdowns to go along with 24 carries for 155 yards and two touchdowns. As the Rams went to the Super Bowl LVI against Cincinnati, Woods tore an ACL in practice in November of 2021 to end the season after 45 catches for 556 yards and five TDs in nine games. After playing in Tennessee, Houston and Pittsburgh, Woods signed a one-day contract to retire with the Rams on February 17, 2026 and become a receivers coach.

Have you heard this story:

Lonzo Ball, Chino Hills High basketball (2012-13 to 2015-16), UCLA basketball (2016-17), Los Angeles Lakers guard (2017-18 to 2018-19):

LaVar Ball has two older brothers, LaFrance and LaValle. He has two younger brothers, LaRenzo and LaShon.

He also has three sons: Lonzo, LiAngelo, and LaMelo.

Even though they had their own Facebook reality show, “Ball in the Family,” this 21st Century version of “My Three Sons” was nothing close to a family affair to remember. When the family was named the 2017 Southern California News Group Sports Persons of the Year, it was based on entities such as SBNation.com calling them disruptors. TheRinger.com refered to Lonzo Ball as a “Superstar for the Reddit Generation.” TheComeback.com said “sports content producers need eyeballs right now, and they’ve found a savior in Lonzo and LaVar Ball.”

It all started at Chino Hills High, Lonzo Ball was the No. 3 ranked player in the country following a senior season when he averaged a triple-double: 23.9 points, 11.3 rebounds and 11.7 assists (plus 4.7 steals) on a team that went 35-0. In 2025, MaxPreps’ list of the Top 10 California high school athletes of the 20th Century, Ball was listed at No. 2. On its list of the Top 25 high school basketball players in the country in the 21st Century, Ball was No. 6.

When LaMelo scored 27 points in his summer high school debut as a 13-year-old, the momentum of forming a once-in-the-lifetime team with three brothers leading the way was unstoppable. With younger brothers LaMelo and LiAngelo, as well as future USC star Onyeka Okongwu, Lonzo Ball pushed Chino Hills to an average of 98.4 points a game, going over the 100-point mark 18 times as the team was ranked No. 1 in the country. The reason the three brothers played together is because father LaVar pushed LiAngelo up a year to get into high school earlier.

Three of the starters would become NBA first-round draft picks — Lonzo, LaMelo and Okongwu. LaMelo would eventually have a 92-point game at Chino High. LiAngelo, after an abrupt end to his UCLA career, became a rapper. Eli Scott, the fifth starter, became a star at Loyola Marymount.

“Their legacy was putting Chino Hills on the map during a five-month basketball run that entertained fans at a level no school has reached since,” the Los Angeles Times’ Eric Sondheimer wrote in 2025, 10 years later.

In one year at UCLA, Lonzo Ball led the nation with 7.6 assists a game, shot 72 percent from the field for 2-point shots, averaged 14.6 points a game and was a consensus All-American. The Bruins started 13-0 and finished 31-5 when they fell out of the Sweet 16.

What else were the hometown Lakers supposed to do with the No. 2 overall pick in the 2017 draft? Pick the guy who wore No. 2 as a high school and college star. Because by then LaVar Ball did everything else but speaking it into existence with his Big Ball Brand, which included a controversial shoe launch and other strange items for sale. LaVar’s shtick was too irresistible for “Saturday Night Live” to parody.

Lonzo Ball signed a multi-year contract the next month and Magic Johnson said he would break all his franchise records. Before his 20th birthday in August, Lonzo was the NBA Summer League MVP in Las Vegas, then the youngest in NBA history to post a triple-double once the season started. He cut off his locks so he didn’t look like Sideshow Bob, left it to others to talk up his potential, and when last we checked in, he was listening to LeBron James’ take about some possible L.A. relocation plans.

ESPN was using him in commercials promoting their telecasts as “the Lakers’ new face of ‘Showtime’.” Two years later, after the Lakers failed to make the playoffs both times, Lonzo Ball was part of a three-team trade that brought Anthony Davis from New Orleans to the Lakers.

Morley Drury, USC football halfback/quarterback/safety (1925 to 1927):

Why was he called “The Noblest Trojans of Them All”? Mark Kelly, a former sports editor of the Los Angeles Examiner, wrote it about him, paraphrasing a line from Shakespeare that referred to Julius Caesar as the “noblest Roman.” Coach Howard Jones, who arrived at USC at the same time as Drury and included him in his Thundering Herd offense where the tailback was in a single wing formation, called him “the greatest player I ever coached,” as Drury also played basketball, water polo and ice hockey for the school.

A Long Beach Poly grad at age 21, he worked two years in the shipyard docks as a roughneck on Signal Hill after finishing grammar school and entering high school. He led Poly to a CIF football title in 1924 and then its basketball team to a state title). As USC was 27-5-1 in his career, Drury became the Trojans’ senior captain and first All-American player. His 1,163 yards rushing in ’27 stood as a school record until Mike Garrett broke it (1,440) during his 1965 Heisman Trophy season of 1965. Drury also had a 45-carry game in ’27 (part of his 223 carries), a mark that wasn’t passed until O.J. Simpson had 47 in 1968. Drury’s legend also includes his a 180-yard, three touchdown game against Washington in his final game that, as he left the field, apparently prompted a 10-minute standing ovation by 70,000 at the Coliseum (also prompted by the public address announcer who said “Morley is coming off the field the last time, folks, give him the hand that he deserves.”) Drury later said he had just scored and Jones told him that instead of going to the dressing room he should walk across the field. “I reached the track (circling the field) and looked up at all those people … my knees got so weak even if I did feel fresh as a horse, and I bawled like a baby. The opposing team stood up. The ovation lasted until I reached the tunnel.” Elected to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1954, he was in the first USC Athletic Hall of Fame class of 1995.

Darryl Henley, UCLA football defensive back (1985 to 1988): The Damien High of La Verne star became a consensus All-American as a senior as the 5-foot-9 and 163 pounder returned the opening game’s opening punt 89 yards for a touchdown in the Bruins’ 59-6 win over San Diego State. He went to the Los Angeles Rams in the second round of the NFL draft and things went sideways. His complete bio is in the No. 20 post, the number he wore for the Rams.

Gianna Bryant, Mamba Academy: The Lakers could still retire No. 2 — if only to honor Kobe Bryant’s daughter, who died in the 2020 helicopter crash with him and wore that number. When the Lakers honored the Bryants in the first game after the tragedy, Gianna’s No. 2 was draped over the seat in which she last sat at Staples Center next to her dad’s No. 24.

We also have:

Jessica Mendoza, Camarillo High softball shortstop (1994 to 1998)

Darren Collison, UCLA men’s basketball (2005-06 to 2008-09)

Taylor Mays, USC football defensive back (2006 to 2009)

Andrelton Simmons, Los Angeles Angels shortstop (2016 to 2020)

Freddie Patek, California Angels second baseman (1980 to 1981)

Alexei Zhitnik, Los Angeles Kings defenseman (1992-93 to 1994-95)

Matt Green, Los Angeles Kings defenseman (2009-09 to2-2016- 17)

Terry Harper, Los Angeles Kings center (1972-73 to 1974-’75)

Zoilo Versalles, Los Angeles Dodgers shortstop (1968)

Don Demeter, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (1959 to 1960) Also wore No. 27 in 1958 and No. 7 in 1961

Sandy Alomar, California Angels infielder (1971 to 1972) Also wore No. 4 from 1969 to ’71 and No. 24 from 1973 to ’74

Bobby Dollas, Mighty Ducks of Anaheim defenseman (1993-94 to 1997-98)

Cam Fowler, Anaheim Ducks defenseman (2011-12 to 2023-24) Also wore No. 54 in 2010-11.

John McNamara, California Angels manager (1983 to ’84, 1996)

Cookie Rojas, California Angels manager (1998)

Anyone else worth nominating?

3 thoughts on “No. 2: Tommy Lasorda”