This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 5:

= Reggie Bush: USC football

= Albert Pujols: Los Angeles Angels

= Robert Horry: Los Angeles Lakers

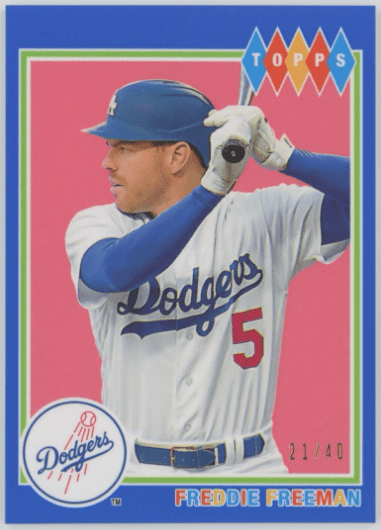

= Freddie Freeman: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Kenny Easley: UCLA football

= Baron Davis: UCLA basketball, Los Angeles Clippers

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 5:

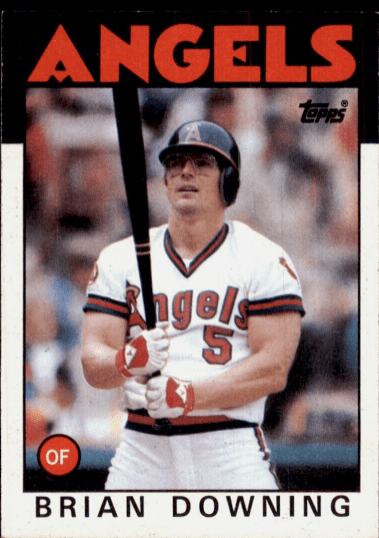

= Brian Downing: California Angels

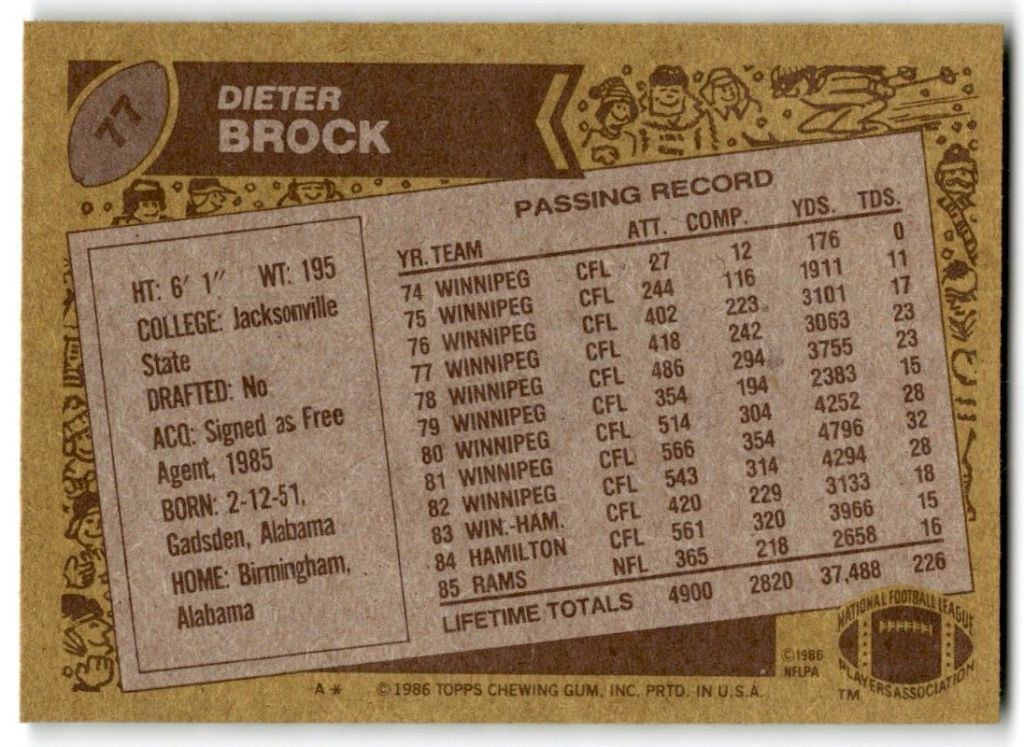

= Dieter Brock: Los Angeles Rams

= Misty May Treanor: Long Beach State women’s volleyball

= Ali Riley: Angel City FC

= Corey Seager: Los Angeles Dodgers

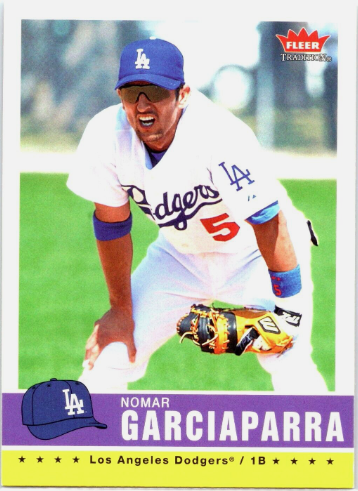

= Normar Garciaparra: Los Angeles Dodgers

The most interesting story for No. 5:

Hunter Greene: Notre Dame High of Sherman Oaks baseball (2014 to 2017)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Sherman Oaks, Stevenson Ranch, Compton, Woodland Hills

Hunter Green might be No. 19-5511 TCX on the Patone color spectrum, described as a cool-tone, earthy, woodland shade that “can evoke feelings of peace and balance, and can also embody growth and new beginnings.”

Hunter Greene — add the “e” on the end of his swatch — wore No. 5 as the Notre Dame High of Sherman Oaks’ pitcher/shortstop/attention grabber when he arrived on the varsity baseball team as a freshman. That was pretty cool unto itself.

Greene found his own inner peace and balance as a two-way star. He wasn’t throwing shade. By the time he reached the end of his senior season, many saw him as Major League Baseball’s next big deal.

In numerology, No. 5 is said to represent flexibility and resilience. It represents the pentagram. It is supposed to bring luck for those intelligent, adventurous and have good communication skills.

Exhibit A: Hunter Greene.

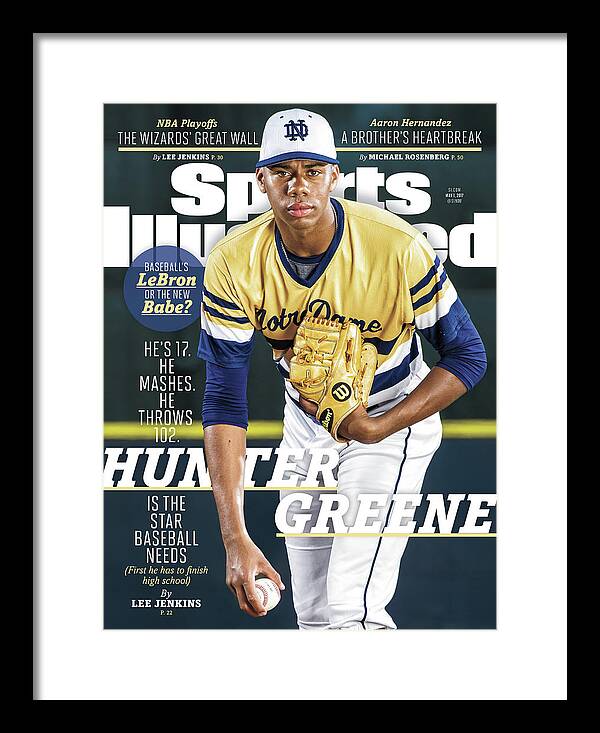

When Sports Illustrated still had cultural relevance and media clout, it presented Hunter Greene to the world on the cover of its April 24, 2017 issue. A few months heading into the Major League Baseball draft, it proclaimed: “Baseball’s LeBron or the new Babe? He’s 17. He mashes. He throws 102. Hunter Greene is the star baseball needs (First he has to finish high school).”

It was suitable for framing.

While SI had put high school athletes on the cover before — less than a dozen — Greene was the first California high school athlete honored. Also, the first African-American prep baseball player on the cover.

Next came the June cover of Sports Illustrated for Kids: “Meet 17-year-old Hunter Greene, the slugging, flame-throwing, violin-playing painter who is on deck to become baseball’s biggest superstar.”

That’s a lot for one teenager to be saddled with. But if anyone might be best equipped to handle that sort of attention, Green, who grew up 20 miles north of the campus up in Stevenson Ranch near Santa Clarita, may have been the too-good-to-be-true story for a three-time All-CIF player.

“People are going to look at him expecting things and he’s still just a kid,” his father, Russell Greene said. “He has to rise to that occasion and he will.”

Eric Sondheimer of the Los Angeles Times whetted the appetite prior to SI with his own profile of Greene a couple months earlier, as the 2017 baseball season started, and the headline called him a “a teenage star in the making.”

“At 6 feet 4 and 211 pounds, with a still-maturing body and a powerful right arm that could lead to a $9-million signing bonus, Greene … scored 31 on the ACT and is on a first-name basis with many in Major League Baseball’s hierarchy, from the commissioner, Rob Manfred, to Hall of Famers Joe Torre and Tommy Lasorda. This smart, humble, communicative teen could be an ideal role model to perform on baseball’s highest stage.”

He was serving up 100-mph-plus fastballs in the recent winter league games.

He had become a fascinating fielding shortstop whose “power is only getting better since his 5-foot-10 freshman days when he batted just .122 on varsity. He has since hit .419 and .390 in the last two seasons. His improvement has been both consistent and dramatic.”

Green had the green light to do big things.

Notre Dame of Sherman Oaks already had experience in big-name baseball players around the MLB draft.

It once had the No. 1 overall pick — shortstop Tim Foli, who grew up in Canoga Park and went to the New York Mets in 1968 (ahead of the Yankees taking Thurman Munson). Foli debuted as a 19-year-old, turning down a baseball/football scholarship at both USC and the University of Notre Dame. He lasted 16 seasons, including two with the California Angels. This SI feature on a 24-year-old Foli and his Playboy bunny wife in 1975 is quite something as well.

Pitcher Jack McDowell, born in Van Nuys, had been a 20th-round pick out of NDHS by Boston in 1984, but his stock soared at Stanford University. He went No. 5 overall in ’87 by the Chicago White Sox, became a three-time AL All Star and the ’93 AL Cy Young winner.

Giancarlo Stanton, born in Panorama City, was a second-round pick out of NDHS in 2007 by the Miami Marlins. It led to four NL All Star appearances and the 2017 MVP. This was after he decided against playing at USC and jumping into a pro career.

Greene took all this to another level.

“We had fans trying to get their Sports Illustrated magazine signed by him while we’re trying to get on the bus,” Notre Dame coach Tom Dill said later. “We had lines of people. I had to stop it. I even saw some opposing coaches in the line.”

The SI piece highlighted more impressive things on his life resume:

= “Greene began playing in spikes on 90-foot bases when he was seven. The Dodgers’ area scout met him during a pitching lesson when he was nine, deeming his throwing mechanics flawless. Radar guns clocked him at 93 mph when he was 14, the same year UCLA and USC offered him scholarships, well aware that he probably wouldn’t ever step on campus because his draft stock was already so high.”

= Greene has two younger siblings — in particular, a sister named Libriti diagnosed with leukemia when she was five years old. She went into remission four years later. Libriti and Hunter became very close through all that.

= “At six he started wearing Jackie Robinson’s number 42. At seven he talked with Dan Rather for a piece on AXS-TV about race and his chosen sport. At 13 he won an essay-writing contest that earned him a meeting with Robinson’s daughter, Sharon.”

= As Hunter played at the William S. Hart Pony Baseball complex in Santa Clarita, his father, Russell, a private investigator in his career, heard the racial name rumblings about his son. It was decided to take Hunter three times a week and drive miles away to the Urban Youth Academy at Compton Community College for a more cultural relatable experience. Upon completing second grade, he applied for Alan Jaeger’s week-long summer camp at Pierce College in Woodland Hills, typically populated by high school pitchers.

= “Greene does yoga with a private instructor three times a week. He dabbles in Korean. He wonders if he could ever play ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ on his violin before taking the field. … He spends free periods painting with Joseph Lee, his AP studio art teacher; bright colors and bold images are Greene’s trademarks. … He launched a sock drive this winter for the homeless in downtown Los Angeles, after reading an article about a shortage, then handed out 2,300 pairs on Skid Row. He has received four certificates of recognition from L.A.-area politicians for his community service efforts.”

Greene made only five starts on the mound during his senior year at Notre Dame, throwing 28 innings, striking out 43 and walking four. His final start of the season was against Alemany, where he struck out 13 and allowed two hits in a complete game win. Greene struck out the side in the final inning to seal a three-game sweep of the Mission League rivals.

In his Notre Dame career, he threw 121 1/3 innings and posted a 1.62 ERA.

In the 2017 draft, the Cincinnati Reds had Greene fall into their lap at No. 2 after Minnesota picked first and took shortstop Royce Lewis out of JSerra High in San Juan Capistrano.

The Washington Post noted that Greene was “the most intriguing, most important baseball prospect to arrive in years, if not ever.” The headline of the story: “Young, black and ridiculously good: Hunter Greene may be just what MLB needs.”

This is Doc Gooden, a longtime scout told Bleacher Report. If he played shortstop, he was in the class of Cal Ripken, Carlos Correa or Alex Rodriguez.

When Greene signed a $7.23-million bonus — the largest amount ever for a high school or college player since a new format went into effect with the 2012 draft — it meant he wouldn’t be going to UCLA, where he did accept a scholarship offer. The Reds agreed to pay for four years of college after his pro career ends. So he can still go to the school where Jackie Robinson played.

“He’s always had a mission of being a good representative of baseball in general,” said Dill. “On the baseball end, he knows it’s a tough sport and has a lot of work to do to continue to get better at the next level.”

The SI story said that if “all goes as planned,” Greene will be part of a MLB team’s pitching rotation by age 20, and no longer need his 33 1⁄2-inch, 30 1⁄2-ounce Marucci bat.

Given No. 79 in 2022 spring training, Greene was upgraded to No. 21 when he made it into the Reds’ starting rotation at age 22. The delay was Tommy John elbow surgery in 2019 and post-COVID restrictions for his rehab.

Greene’s debut was a five-inning start against Atlanta, not allowing a hit over the first three innings, striking out seven and giving up two runs to get his first win on April 10, 2022.

Six days later, his second start came at Dodger Stadium before dozens of family and friends. Greene reached or exceeded 100 mph 39 times — more often than any other pitcher since pitch tracking began in 2008. And he only pitched into the sixth inning. The average speed of his 57 fastballs was 100.2 mph.

By the ’23 season, Greene signed a six-year, $53-million extension that could reach $90 million with incentives and a club option in 2029.

Listed at 6-foot-5 and 242 pounds when he started his third season in ’24, Greene was back to averaging 97.7 mph with his fastball and found himself among the league leaders in ERA and tops in WAR at 5.3. He was added to the NL All-Star team as a replacement for injured Dodgers starter Tyler Glasnow.

Entering in the fifth inning of a 3-3 tie in Arlington, Tex., Greene was one pitch away from producing a perfect clean inning. But Boston’s Jarren Duran, another Southern California product from Claremont, hit one of Greene’s splitters for a two-run homer, and Greene ended up as the game’s losing pitcher.

“Being an All-Star is a huge privilege,” Greene said, before posting a 3-0 record and 1.09 ERA in five starts after the 2024 All-Star break. “It’s a blessing. When you can get an All-Star [selection] this early in your career, I think it propels you in a lot of different ways.”

Starting in 2018, just seven months into his pro career in the minor leagues, the Hunter Green Baseball Camp at Darby Park in Inglewood was launched. It drew 400 campers age 9 to 14, volunteers, parents and coaches for best practices sharing. Part of the program was a leadership seminary by Greene’s mother, Senta Greene, an educational consultant. She shared about her son’s integrity, humility, compassion, courage and discipline. He also talked about how the times Hunter would get dressed for games in a hospital room while visiting his sister through her cancer treatments. The camp has since moved to Compton and now is in Cincinnati.

“When I was at the Youth Academy (in Compton), we had a lot of instructors come in and professionals work with us and it was very special,” said Greene. “Other kids who weren’t at the academy weren’t fortunate enough to have that. They were playing travel ball or just at their local league. They weren’t getting special coaching. So for me to be able to do that with these kids and for them to be exposed to that is going to help them a lot.

“It’s about that foundation. Being able to see what this game expects form you at a young age, just so you know and are ahead of the curve compared to everyone else. The experience that you have and just knowing what to expect helps you a lot to navigate through there.”

In 2023, a day before the April 15 Jackie Robinson Day, Greene made a surprise visit to a group of baseball and softball students at Cincinnati Public School’s Robert A. Taft Information Technology High School.

“Something that I live by through him is always being inclusive,” Greene said, wearing Robinson’s No. 42 again for the kids. “No matter what a person’s background is, where they come from, their financial status or whatever the case is, being inclusive is about always being somebody that’s able to make someone else feel at home and welcomed as much you can. Whether it’s in the classroom, with teammates, friends or whatever it is. That’s something that Mr. Robinson was able to do and that’s my biggest take away from him.”

In February of 2024, Greene returned to Notre Dame High for a ceremony honoring the recipients of the Hunter Greene ‘17 Endowed Scholarship Fund. The school’s website explains how it was founded “to help close the financial gap for African American students who have limited financial resources, allowing them to have an equal opportunity to be successful while at Notre Dame High School and beyond.”

In November of ’23, he hosted a cleat giveaway in late November in Chino Hills where he played in tournaments in as a kid.

Greene has been the Reds’ nominee for the annual Roberto Clemente Award, Major League Baseball’s annual recognition of a player who best represents the game through extraordinary character, community involvement, philanthropy and positive contributions, both on and off the field.

Reds president of baseball operations Nick Krall said it in August, ’24: “He’s learning how to be a big league pitcher. I think we take that for granted sometimes when you’ve got a 22-, 23-year-old trying to work their way into this game. And then once they become 24, 25, 26, they start getting into their prime and they become elite players. He’s always been an elite talent, but now he’s really worked hard, he’s worked his butt off to develop into the pitcher he’s become this year.”

To start the 2025 season, Greene began an 18 ⅔-inning scoreless streak that included several career-high water marks. An April 7 start in San Francisco marked the first time he pitched into the ninth inning, falling just one out shy of completing a four-hit shutout. In the ninth inning, on his 88th pitch, Greene’s fastball was clocked at 100.7 mph. A strained right groin muscle sidelined him for 2 ½ months, but he went 3-1 with a 2.81 ERA in eight starts after returning from the injured list, including a one-hit shutout against the Chicago Cubs. The Reds won five of his starts, and needed every single one of them, earning a playoff berth on the final day of the regular season. Green started Game 1 of the NL Wild-Card Series against the Dodgers at Dodger Stadium and endured an eventual 10-5 loss, lasing just three innings.

It was pointed out in a USA Today story about how his MLB progress may not have been as large a splash as anticipated that Greene’s “non-linear path to fulfilling potential isn’t just for long-shot prospects or slumping hitters. Sometimes the can’t-miss flamethrower, the bluest chip in the stack, needs a minute to get there,” wrote Gabe Lacques.

“But you know, there’s beauty in that,” Greene said, “in being able to figure out ways to become a better player and a better person and be able to grow. To add to your development and process. I was able to do that. I was able to come back better in a lot of different ways. And it’s made me better as a person, too.”

Who else wore No. 5 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

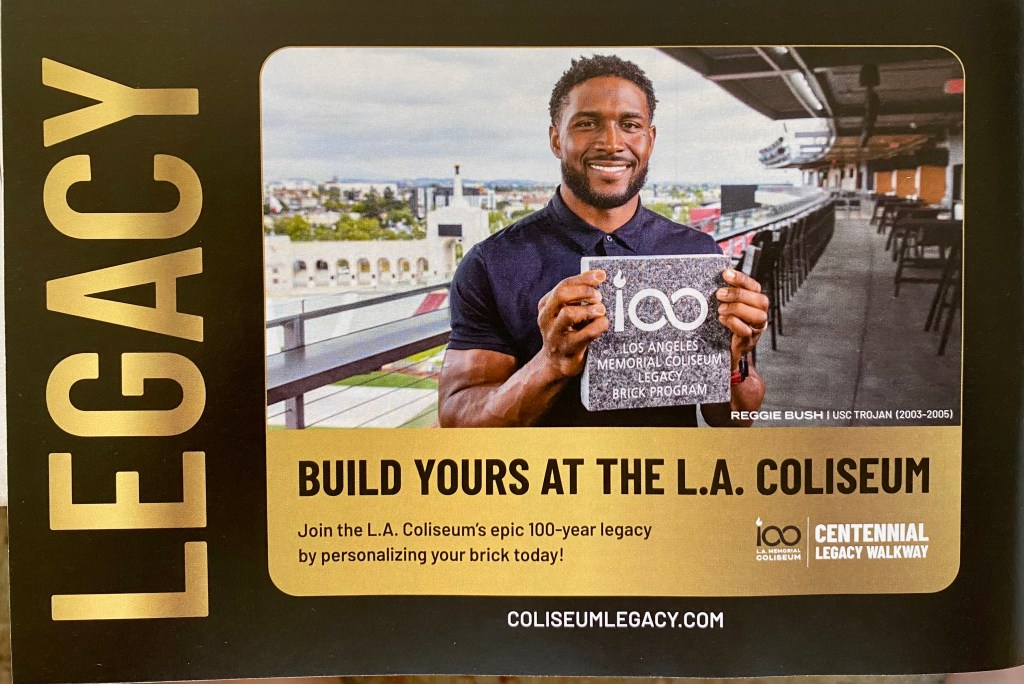

Reggie Bush, USC tailback (2003 to 2005):

On Dec. 30, 2010, I wrote an essay that started: “We hesitate to trumpet the announcement of the 2010 Daily News Sports Person of the Year, for fear and disappointment someday we’ll have to list it as ‘vacated.’ To satisfy our requirements for the time being, we’ll handle it this way: Congratulations, Reggie Bush*.

Five years earlier, Bush was celebrated as the first Daily News Sports Person of the Year, sharing the honor with then-USC teammate, Matt Leinart. The No. 1 ranked Trojans were riding a 35-game win streak into the 2006 national championship game against Texas just days away.

In both instances, the choice of Bush was strictly based about how much news he generated over the previous 12 months. Good or not so good. I

What came out in ’10 was less than perfect.

It’s easy to be dazzled by the all-purpose Reginald Alfred Bush II, USC royalty for three collegiate football seasons. Out of Helix High in the San Diego suburb of Spring Valley, Bush was deemed the No. 1 prep running back in the nation and a track star as well when Pete Carroll recruited him as what he called a five-way threat — running, catching, throwing, returning punts and returning kickoffs.

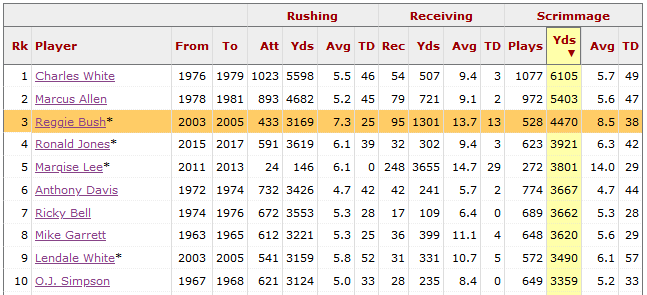

Bush ended up No. 3 on USC’s list of all-purpose yards, and likely would have soared past Charles White and Marcus Allen had he stayed for his senior season.

Bush had touchdowns carrying the ball (25), catching the ball (13), returning the ball (4) and even throwing the ball (a 52-yard scoring play to Dwayne Jarrett against Arizona State in 2004). Even the most famous touchdown he was part of where he didn’t score — The “Bush Push” game in South Bend, Ind., from 2005 — became part of his lore.

He had the NCAA record for highest yards-per-carry average at 7.3. He put together a record 554 yards in back-to-back games. He had two seasons with more than 2,000 all-purpose yards.

He had two of the top six greatest rushing days in Trojan history. The 513 all-purpose yards he had against Fresno State in 2005 (294 rushing, 68 receiving, 151 returning) is second all-time in the NCAA record book. The 260 yards rushing in a 66-10 win over UCLA in 2005 only punctuated the moment of claiming the city title.

He started just 14 times in his 39-game career at USC and finished 10th in NCAA history with more than 6,500 all-purpose yards.

On Dec. 10, 2005, Bush won the Heisman Trophy Award, accruing 784 first place votes, far more than Texas quarterback Vince Young (79 votes) and teammate (and defending Heisman winner) Matt Leinart (18 votes). Bush had the second-greatest number of first-place votes in Heisman voting history behind O.J. Simpson’s 855 in 1968. Maybe that’s appropo to have Bush and Simpson linked in Trojan lore.

In the 2006 national title game at the Rose Bowl, Bush added 279 all-purpose yards — 82 rushing, 95 receiving, 102 kickoff returns, one TD — in the Trojans’ loss to Young and Texas. His low-light from that game was, with USC up 7-0, trying to lateral the ball after a long run-after-catch in the second quarter,. It fell away 20 yards from the end zone as a fumble and was recovered by Texas.

Things would get fumbled away even more dramatically from there.

In 2008, a book entitled “Tarnished Heisman: Did Reggie Bush Turn His Final College Season Into a Six-Figure Job,” came out by Don Yaeger sorted all out the information been swirling about Bush since the 2006 NFL Draft.

There was a narrative started that Bush and his family received improper from a fledgling agent, against NCAA rules. By the summer of 2010, the NCAA determined the collected evidence was legit enough to punish USC, even as Bush didn’t want to cooperate. That likely made things worse.

Agent Lloyd Lake and his partner, Michael Michaels, decided they not only wanted to represent Bush in his pro career, but they had laid the groundwork. They hired a limo for the Bush family to take them to the 2005 Heisman presentation. They also gave his parents use of an upscale rented house.

Bush stood by his innocence. The USC coaches claimed ignorance.

The result: Four years probation for USC, vacate the 2005 Orange Bowl win (and its national title win over Oklahoma), 30 scholarships taken away over the next three years, no bowl bowl games for 2010 or 2011. USC was also forced to “disassociate itself” from Bush.

Then-USC president “Max Nikias ordered that the school’s replica of Bush’s Heisman Trophy be removed from the athletic department lobby and returned to New York.

Lake then sued Bush to get his money back. Bush reached a settlement with him — again, not admitting guilt.

USC’s own media guides were updated. Any reference to Bush came with an asterisk that referenced: “Participation in the last two games of 2004 and all of 2005 later vacated due to NCAA penalty.”

The Heisman organization, never in this position, wondered how it could keep Bush on its list of winners. Bush remained the team’s choice for Most Valuable Player for ’04 and ’05,. He retained the 2005 Walter Camp and Doak Walker awards. His image remained on the cover of the EA Sports NCAA Football 2007 video game — which Bush was never compensated for, nor did he ever collect royalties on the No. 5 jerseys sold at the USC store.

Bush voluntarily gave back his Heisman Trophy in 2012. Even as he claimed he did nothing wrong. The Heisman people struck him from its list of winners.

The mixed message was baffling.

In 2021, the NCAA ruled, perhaps against its better judgment but mostly from public pressure, that a player can make money from his name, image and likeness. The whole business world of college sports pivoted.

In April of 2024, the Heisman group reinstated Bush. It was in no way overruling the NCAA’s decision that he broke rules. USC decided it would end its 10-year separation from Bush.

“We considered the enormous changes in college athletics over the last several years in deciding that now is the right time to reinstate the Trophy for Reggie,” said Michael Comerford, president of the Trust.

“Well well well … look what we have here,” Bush tweeted soon after the announcement. He tweeted again “in regard to the reinstatement of my college records and my Heisman” and added: “It is my strong belief that I won the Heisman trophy ‘solely’ due to my hard work and dedication on the football field and it is also my firm belief that my records should be reinstated.”

He had previously tweeted: “I never cheated this game. That was what they wanted you to believe about me.”

Those remarks are consistent with Bush’s lack of contrition for what his and his family’s transgressions did to the program.

“The people at the university bailed on me,” he once said in 2018.

In another story from ’18 he added: “I was just told don’t take money from boosters. OK, I didn’t do that. The guy who I took money from was my boy. I had known him for eight years. The way I was explained the rules you have to have known the person for four years or more. This guy was a family friend.”

As Los Angeles Times columnist Bill Plaschke wrote: “It’s not that Bush didn’t break the speed limit, it’s that the speed limit has changed. And indeed, judging by today’s high salaries for top college football players, Bush was actually severely underpaid for his efforts. But that doesn’t change the fact that, at the time, he was still receiving extra benefits when players weren’t supposed to receive extra benefits. The rules stank, but the rules were the rules, and everyone knew them, and Bush allegedly broke them, and no shiny trophy is going to change that.”

Bush was inducted into the National Football Foundation’s College Football Hall of Fame in 2023. His bio starts: “One of the most dynamic players in the history of college football … helped Southern California claim two national championships and a 37-2 record during his three years playing in the Coliseum (and) now becomes the 34th Trojan to enter the College Football Hall of Fame.”

In ESPN’s 2020 list of the 150 greatest college football players in the game’s first 150 years, Bush ranked No. 61 noting that “few players in history left indelible marks during — and after — their college careers the way Bush did.”

Bush never wore No. 5 in his 11-year NFL career. He went with No. 25 (in New Orleans, which drafted him second overall in 2006, kept him until after its 2010 Super Bowl title and in 2019 put them into their team Hall of Fame), No. 22 (in Miami for 2011 to ’12; in Buffalo for 2016); No. 21 (in Detroit for 2013 to ’14) and No. 23 (in San Francisco for 2015). He made $63 million in salary as a pro player.

In the fall of ’23, Bush put his comeback campaign in more murky waters by filing a defamation suit against the NCAA. Bush petitioned the NCAA for reinstatement in light of the NIL ruling, but the NCAA declined, reiterating its rules “still do not permit pay-for-play type arrangements.” That’s a key explanation of what’s going on here. But Bush still seems to confuse the issues, saying in an interview with The Athletic he is glad future college athletes won’t face situations similar to his.

“I’m good with what happened to me because it had to happen to me so we could get to this point,” Bush has said. “Kids will no longer be told they can’t make money off their names while their school makes millions off of them. Thousands of kids now will be able to make money off their name and likeness, be able to support their families that need help, and have a little extra to be able to even put good healthy food on the table and pay bills.”

In the fall of 2024, Bush pushed back with another lawsuit, naming USC, the NCAA and the Pac-12 liable for him getting back payments for lost NIL. USC was reportedly added to the lawsuit because it declined to help Bush pay legal fees intended to only seek damages from the NCAA and the Pac-12.

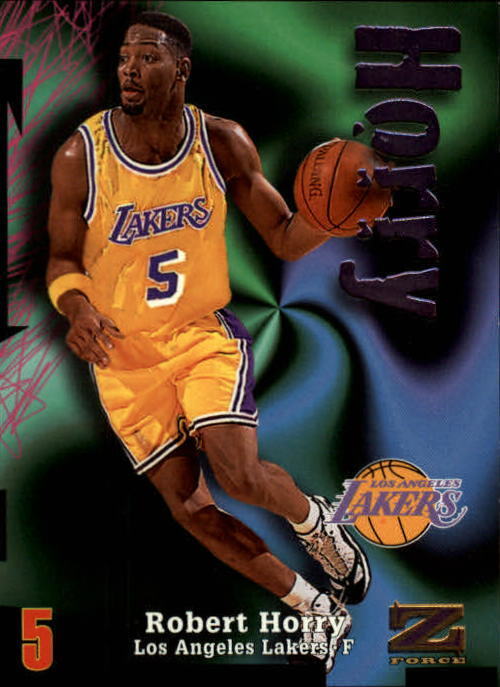

Robert Horry, Los Angeles Lakers forward (1996-97 to 2002-03):

The nickname “Big Shot Rob” was all about his impeccable timing for often coming off the bench in clutch situations. In 2001, his 3-pointer with 47 seconds left solidified a Lakers’ Game 3 Finals win over Philadelphia. In 2003, Game 4 of the NBA Finals against Indians, Horry picked up a loose ball and hit a game-winning shot to break a 95-95 tie. In the first round of the 2002 playoffs against Portland, Horry hit a 3-pointer from the corner with 2.1 seconds left to clinch Game 3. His biggest shot was a 3-ponter he drained at the end of Game 4 in the 2002 Western Conference finals as the Lakers, down by two to Sacramento, saw both Kobe Bryant and Shaquille O’Neal miss their shots. The loose ball was tapped away by Kings center Vlade Divac, but it landed in the hands of Horry, who lined up a top-of-the-key shot for the win. That evened the series and keep the Lakers alive to pursue a third straight championship. By the time he was done in a 16-season NBA career, he was part of seven championships and never lost in a Finals series. It may be forgotten history that the only reason Horry became available to the Lakers was because, during his one season at Phoenix, he threw a towel at coach Danny Ainge during an off-court altercation, leading to his suspension and a decision to give him to L.A. in exchange for Cedric Ceballos. Because the Lakers already retired No. 25 for Gail Goodrich, Horry took No. 5.

Albert Pujols, Los Angeles Angels first baseman/designated hitter (2012 to 2021):

The numbers most associated with Pujols as an Angels were 10 years and $254 million — plus a 10-year, $10 million personal services contract — when he came over from St. Louis. He was only the third MLB player in history to break the $200 million barrier, but, at age 32, wasn’t that really rewarding what he did as a three-time NL MVP, nine-time All Star, six-time leader in N.L. WAR and former batting champion with a career average nearing .330? The Cardinals reportedly “only” offered him nine years and a little less than $200 mil, which would have “only” made him the fourth-highest paid first baseman. As an Angel, he was No. 1, thanks to owner Arte Moreno who, in 2003, paid $184 million for the franchise. The future Hall of Famer collected his 500th career homer in 2014 and 3,000th career hit in 2018. His one AL All-Star appearance with the Angels was in 2015, age 35, when he reached 40 homers for the only time in Anaheim. His 10-year run with the Angels, where his stats seemed to be most affected by the prevailing defensive shifts put upon him: .256 batting average in 1,181 games, 1,180 hits, 222 homers and 783 RBIs.

Kenny Easley, UCLA football defensive back (1977 to 1980):

It was reported that more than 300 colleges recruited him after his prep days in Virginia, but the Bruins head coach Terry Donahue, in his second season at the school, landed Easley. The 6-foot-3, 205-pound safety told the Los Angeles Times that on the flight to Houston before his first game, he was told he would share time with UCLA veteran teammate Michael Coulter. “(He) started the game and played the first two quarters, I played the second two, and Michael never played again,” said Easley. He had nine interceptions and 93 tackles, records for a true freshman, four more picks as a sophomore and, by the time opponents figured out now to throw his way, finished his four years with a school-record 19 interceptions, a three-time consensus All-American and the first in Pac-10 history to become all-conference four years in a row. Also a dynamic punt returner, Easley, known as “The Enforcer,” was ninth in the ’80 Heisman voting (with five first-place votes) and had 374 career tackles, among the top five in school history. He landed in the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame as well as the College Football Hall of Fame in 1991. Little known fact: Easley played JV basketball at UCLA and was picked by the NBA’s Chicago Bulls in the 1981 Draft, but for some reason choose a career in the NFL with Seattle (the fourth pick overall) and ended up in the Pro Football Hall of Fame (known for wearing No. 45) inducted in 2017. In ESPN’s 2020 list of the 150 greatest college football players in the game’s first 150 years, Easley was ranked No. 114 with this tribute: Racism died hard in the Virginia of the 1970s, which is why Easley fled Norfolk for the West Coast. He quickly established himself as a force in the Pac-10. In a league that featured the power running of USC and the West Coast offense of Stanford, Easley brought the size and speed necessary to deal with both. Easley died in 2025 at age 66 after a long battle with kidney issues. UCLA retired his No. 5 jersey in 1991.

Baron Davis, UCLA basketball guard (1997-98 to 1998-99), Los Angeles Clippers guard (2010-11):

The No. 1 recruit in the nation out of Santa Monica’s Crossroads School — the Gatorade and Scholastic Coach National Player of the Year during his well-heralded four-year career — stayed home and spent two seasons at UCLA. He ended up averaging 13.6 points with 5.1 assists and 2.5 steals, was a Pac-10 All-Freshman Teamer and the Pac-10 Freshman of the Year in 1998, as well as an All-Pac-10 First Teamer and a Third-Team All-American during his sophomore season in ’99. His time at UCLA was interrupted by an ACL injury during the 1998 NCAA Tournament’s second round. He was inducted into the UCLA Athletics Hall of Fame in 2016. The No. 3 overall pick by Charlotte in the 1999 NBA Draft, he circled back to L.A. to play for the Clippers for three seasons, he wore No. 1 from 2008-09 to 2009-10 before taking No. 5.

Corey Seager, Los Angeles Dodgers shortstop (2015 to 2021):

The 2016 NL Rookie of the Year for his .308 batting average, 26 homers, 72 RBIs and 40 doubles came after he introduced himself in 2015 as a 21-year-old who hit four homers and drove in 17 during 113 plate appearances in 27 games — just enough to maintain his rookie status going forward. The Dodgers’ 2012 first-round draft pick lasted seven years in L.A., included two NL All-Star appearances, two Silver Slugger Awards and the 2020 NLCS and World Series MVP recognition during the COVID campaign. Seager’s back injuries in 2018 and 2021 seemed to sour the Dodgers on giving him a contract extension with his free-agent status came up. Texas did, and a 10-year, $325 million deal may have paid some dividends when he was the Rangers’ 2023 World Series MVP and second in the AL regular-season MVP voting.

Freddie Freeman, Los Angeles Dodgers first baseman (2022 to present):

The 2024 World Series MVP carved a spot for himself in the game’s post-season lore before the votes were even counted following the Dodgers’ five-game series win over the New York Yankees.

His 10th inning walk-off grand slam was a Kirk Gibson-like magical moment, as he celebrated it with his father, Fred, standing at the backstop screen. Freeman then hit home runs in Games 2, 3 and 4 and drove in two key runs in the Game 5 finale. He was 6-for-20 with a World Series record-tying 12 RBIs and a 1.364 OPS while playing on a very sore right ankle (twisted at the end of the regular season) as well as a broken rib — and having missed games in the regular season to care for his ailing son. Born in Fountain Valley, growing up in Villa Park, and the Orange County Register’s 2007 player of the year at El Modena High, Freeman signed a letter of intent to go to Cal State Fullerton before he was drafted in the second round of the MLB selection by Atlanta. Three times an NL All Star in the first three seasons of his six-year, $162 million Dodgers contract, Freeman played his first 12 years as a five-time All Star in Atlanta and 2020 NL MVP. Freeman led the NL with 59 and 47 doubles in ’22 and ’23 as a Dodger and was fourth and third in the NL MVP voting those two seasons. His .407 OBP, 117 runs and 199 hits were also tops in the NL in ’22, even as he exceeded all three titles in ’23 (.410, 131 and 211) to go with 29 homers and 102 RBIs — and a career-best 23 stolen bases.

In the 2025 World Series, Freeman may have been only 6-for-29 in the seven games, but he ended the 18-inning Game 3 marathon with a solo homer to center field for a 6-5 Dodgers win. That made him the only player in MLB history to have two walk-off homers in World Series competition.

Nomar Garciaparra, Los Angeles Dodgers infielder (2006 to 2008):

The Whitter native and former St. John Bosco standout — maybe better known for his team-high 17 goals on the soccer field as a junior — made his return to L.A. when the Dodgers signed him a 31-year-old free agent. His nine years in Boston (five-time All Star) ended just before the Red Sox broke their curse and won the 2004 title. He was traded to the Chicago Cubs and didn’t seem to have much left for two injury-plagued seasons. But with the Dodgers as a first baseman, he returned to All-Star form, hitting.303 with 20 homers and 93 RBIs in ’06. The highlight of that season was his two-run homer in the 10th inning during a Sept. 18 game at Dodger Stadium against first-place San Diego, punctuating the fact the team collected four consecutive home runs in the bottom of the ninth to tie it, the last two against reliever Trevor Hoffman. Garciaparra’s home run gave the Dodgers an 11-10 win and moved them into first place. “When I was rounding the bases, I couldn’t wait to get home and hug everybody. It was like a group hug, because it was a group effort,” Garciaparra said. It earned him a bobblehead giveaway night in 2007.

Brian Downing, California Angels catcher/outfielder (1978 to 1990):

His induction into the Angels Hall of Fame in 2009 was bittersweet. The graduate of Magnolia High of Anaheim who also played at Cypress College came to the Angels in a 1977 off-season trade with the Chicago White Sox to be their top catcher (along with pitchers Chris Knapp and Dave Frost, in exchange for Bobby Bonds, Thad Bosley and Richard Dotson). Downing became the gem of that deal as he became known as “The Incredible Hulk” for his weight-lifting regime. He made the AL All Star team a year later (the one and only time) and went the ’82 and ’84 seasons without making an error. But then he was moved to left field, and Downing set an AL record of going 244 errorless games. He moved into the DH spot in ’87, was moved to the leadoff role, and led the AL with 106 walks. Part of the Angels’ first three West Division titles, Downing was, after 13 seasons, the franchise leader in games, hits, homers, RBIs, walks and sacrifice flies. He hit a career-best .326 when the Angels won the ’79 AL West. But he remained bitter that he was somehow allowed to go to Texas for his last two seasons. Of note: After two seasons wearing No. 5 for the Angels, he assumed No. 9 for the 1980 season, giving the digit away to up-and-coming third baseman Carney Lansford, in the last of his three seasons as the Angels infield. Downing got it back for the last nine seasons of his Anaheim stay after Lansford left to Boston.

Misty May-Treanor: Long Beach State women’s volleyball (1995 to 1999):

The 49ers women’s volleyball program retired May’s No. 5 jersey and put the standout setter into the school’s Athletic Hall of Fame in honor of her numerous achievements — the Honda-Broderick Cup for best female college athlete in ’98-’99, back-to-back NCAA national play of the year awards, captain of the 1998 team that went undefeated (36-0) and won the national championship as she was named NCAA Championship Most Outstanding Player with a record 20 service aces. Prior to that she was an All-CIF Division I Player of the Year at Newport Harbor High in Costa Mesa, winning state titles as a sophomore and senior (1992 and ’94) and named USA Today’s best high school girls volleyball player. May’s global fame, however, turned out to be on the beach. Teammed with Holly McPeak, May made it to the 2000 Summer Olympics before losing in the quarterfinals. May then teamed up with Kerri Walsh playing on the international circuit before dominating the AVP, at one point winning 112 straight matches and 19 straight tournaments. They won Olympic beach volleyball gold medals in 2004, ’08 and ’12, and May retired after the final championship. A Distinguished Alum of CSULB, she was inducted into the Volleyball Hall of Fame in 2016 and the USA Volleyball Hall of Fame in 2019.

Ali Riley, Angel City FC defender (2022 to 2025):

Out of Harvard-Westlake in North Hollywood, where she was a two-time Mission Leagues Offensive MVP and helped her team win the CIF Southern Section Division I title in 2006, Riley competed on local soccer clubs such as the L.A. Breakers FC and Real SoCal before going to Stanford. After playing for various teams in the U.S. and overseas in England, Germany and Sweden, she came back to the U.S. to play in the National Women’s Soccer League. Traded to the expansion Angel City FC, she played in her hometown for the first time in her career, starting as a defender and was named team captain She scored her first goal in 2023. But in 2024, she was put on a season-ending injury list with a chronic nerve injury in her left leg that forced her to miss the Summer Olympics. Riley, who is of Chinese and New Zealand descent, played on the New Zealand national team. After playing in five World Cups and five Olympics, Riley announced she would retire after the 2025 NSWL season.

Mark Collins, Cal State Fullerton football defensive back (1982 to 1985): The PCAA Defensive Player of the Year in 1985 set a school career record with 20 pass interceptions and was a second-round draft pick of the New York Giants, playing 13 seasons in the NFL including All-Pro status and in two Super Bowls.

Kevin Ingram, Los Angeles Avengers receiver/defensive back (2002 to 2008): The 6-foot-1, 195-pounder from West Chester University in Pennsylvania led the Arena Football League’s L.A. franchise in games played (98), receptions (536), all-purpose yards (9,523), kickoff return yards (2,871) and was second in tackles (308) and interceptions (25). The league made him its “Ironman of the Year” in 2005 as the top two-way player when he led the Avengers with 88 receptions for 1,052 yards and 23 touchdowns as well as six interceptions and 68 tackles.

Bill Stetson, USC volleyball setter (1979 to 1982): The two-time All American was inducted into the Southern California Indoor Volleyball Hall of Fame, he was on the Trojans’ 1980 NCAA title team, runner up in ’79 and ’81, and third in ’82, when, as a senior, he was named Most Outstanding Athlete of the Year by the Pac-10 Conference. He then played for the U.S. National team and, after becoming a successful surgeon — his father was a doctor — was the U.S. National Team physical for the 2012 London Olympics. One of his highest honors came in 2007 when he was selected as the NCAA Silver Anniversary Award winner, the only Trojan men’s volleyball player to win the honor. The youngest of nine children grew up in Torrance.

Mike Marshall, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (1981 to 1989): Not to be confused with the Dodgers’ Cy Young Award-winning relief pitcher of 1974, this Marshall and his 6-foot-5 “Moose” frame was part of the Dodgers’ 81 World Series post-season roster and a key healthy player in their 1988 title run, leading the team in RBIs during the regular season.

Jim McMillian, Los Angeles Lakers forward (1970-71 to 1972-73): When Elgin Baylor retired as a Laker in 1971, McMillian, the second-year pro out of Columbia, was inserted into the starting lineup, and the team ran off a 33-game win streak. That’s just a fact. He averaged nearly 20 points a game on that team that went onto the NBA title, its first in L.A. He had a 42-point game for the Lakers in ’73, which helped his trade value to Buffalo after that season in exchange for center Elmore Smith — because the Lakers needed to fill a void for the retired Wilt Chamberlain.

Jayden Daniels, Cajon High of San Bernardino football quarterback (2015 to 2018):

Before he led the Washington Commanders to the NFC title game in his rookie NFL season, and before he won the Heisman Trophy at LSU, Daniels set CIF-Southern Section career records with 210 touchdowns and more than 17,600 total yards in 53 games — breaking down to 13,732 yards passing and nearly 4,000 rushing. He ran for 1,360 yards and passed for 4,240 yards in 13 games during his senior season, taking his team to a state title game. In a 57-28 win that season over Murrieta Valley, Daniels accounted for 500 yards and six touchdowns — 21 of 33 for 341 yards and five scores passing, and 159 yards and one TD rushing. When he went on to becoming a starting quarterback at Arizona State as a freshman, his high school retired his No. 5. When he won the 2023 Heisman at LSU, throwing for 3,812 yards and 40 TDs with just four interceptions and rushing for 1,134 yards and another 10 TDs, his high school changed the name of its home field to Jayden Daniels Stadium.

Amari Bailey, UCLA basketball guard (2022-23): The 6-foot-5, 185-pound Sierra Canyon High standout averaged 11.2 points, 2.2 assists and 3.8 rebounds a game for the Bruins in 30 games as a freshman, then applied for the NBA draft. Taken in the second round (41st overall), he played just 10 games for the NBA’s Charlotte Hornets in the 2023-24 season, and announced he was going to try to go back to play at UCLA. “Right now I’d be a senior in college,” Bailey told ESPN in a statement in January of 2026. “I’m not trying to be 27 years old playing college athletics. No shade to the guys that do; that’s their journey. But I went to go play professionally and learned a lot, went through a lot. So, like, why not me?” Per ESPN’s report, Bailey hired an attorney to represent him in his case, in which he is looking for the NCAA to give him the right to play one more season. “It’s not a stunt,” Bailey continued. “I’m really serious about going back. I just want to improve my game, change the perception of me and just show that I can win.” While at Sierra Canyon, the three-time All-CIF Open Division honoree was ranked as the No. 1 player in the state of California by ESPN.com and 247Sports.com.

Brayden Burries, Eleanor Roosevelt High of Eastvale basketball forward (2022 to 2025): The 6-foot-5 Burries set a California state Open Division record in one of the greatest individual performances in Southern California history — 44 points and 12 rebounds — during the title win in Sacramento. His coach, Stephen Singleton, said no other Roosevelt player would wear No. 5 on their jersey because his number would be retired. “Best player in Roosevelt history,” he said of the school of the Ontario Airport off I-15 between the I-91 and I-60.

Have you heard this story:

Dieter Brock, Los Angeles Rams quarterback (1985):

Mr. Fancy Hair, coming off 11 glorious seasons in Canadian Football League despite a chronic back injury, became the Rams’ 34-year-old default rookie quarterback for one season. He set an NFL record by winning his first seven starts. He threw for 2,568 yards and 16 touchdowns (to go with 13 picks), set a team record by completing nearly 60 percent of his passes, and the Rams were 11-4 before losing the NFC championship to Chicago. Mostly, Brock was there to hand the ball off to 25-year-old Eric Dickerson. Wrote the L.A. Times’ Chris Dufresne about the way Brock’s career ended a season after riding the bench: “Brock was polite and reserved. He would never get a bit part in Hollywood. He would never model underwear. He was pale-skinned and long-haired. He played football in Canada, for goodness’ sake. The novelty of Brock quickly eroded. He never quite fit in. To his credit he took an abundance of abuse with grace and answered every reporter’s question until, well almost, the very end. No one is or should feel sorry for Dieter Brock. He made more money this year ($250,000 in 1986) for not playing than the average man does in 10.”

Jamelle Holieway, Banning High football quarterback (1982 to 1984):

Before he stepped in for an injured Troy Aikman as the University of Oklahoma and became the first true freshman to lead a team to a national college title running the Sooners’ complicated Wishbone offense in 1985, Holieway dazzled high school opponents with his running and passing ability at Banning High in Wilmington. The 1984 L.A. City player of the year was lured to Oklahome by coach Barry Switzer and combined to run and throw for more than 2,400 yards each during his four years. After leaving Oklahoma, he admitted he received “favors” from boosters. Holieway went undrafted by the NFL, but signed with the Los Angeles Raiders as a wide receiver for the 1989 and ’90 seasons before heading to the Canadian Football League.

Walter Johnson, Fullerton High School pitcher (1904-05):

During his time in high school and professional baseball, Hall of Famer Walter “Big Train” Johnson didn’t wear a number. No one really did. It wasn’t a thing at that point in time.

Johnson just put up numbers that were beyond belief.

Johnson was 14 when his family moved from a rural farm near Humboldt, Kansas to a small oil boomtown in Orange County known as Olinda, just east of Brea. At 17, he was a freshman at Fullerton High in the ninth grade, falling behind two grades after he finished eighth grade in Kansas. Fullerton’s baseball team had no coach and was in no formal league, just playing local schools. His claim to fame at Fullerton High was striking out 27 batters in a 15-inning scoreless tie against Santa Ana High (as reported in the Santa Ana Evening Blade account). The game reportedly wasn’t called on darkness, but umpired thought the pitchers might get injured throwing that long. At the same time, Johnson was playing semi-pro baseball as noted in many of the local newspapers. He didn’t return to Fullerton nearing his 18th birthday, but instead enrolled in Orange County Business College.

Signing a contract with the Washington Senators at age 19 in 1907, he won 417 games against 279 losses with an ERA of 2.17 to go with 3,508 strikeouts (the all-time record for more than a half-century) and 110 shutouts. Primitive measurements clocked his fastball at 91 miles an hour, unmatched in his day.

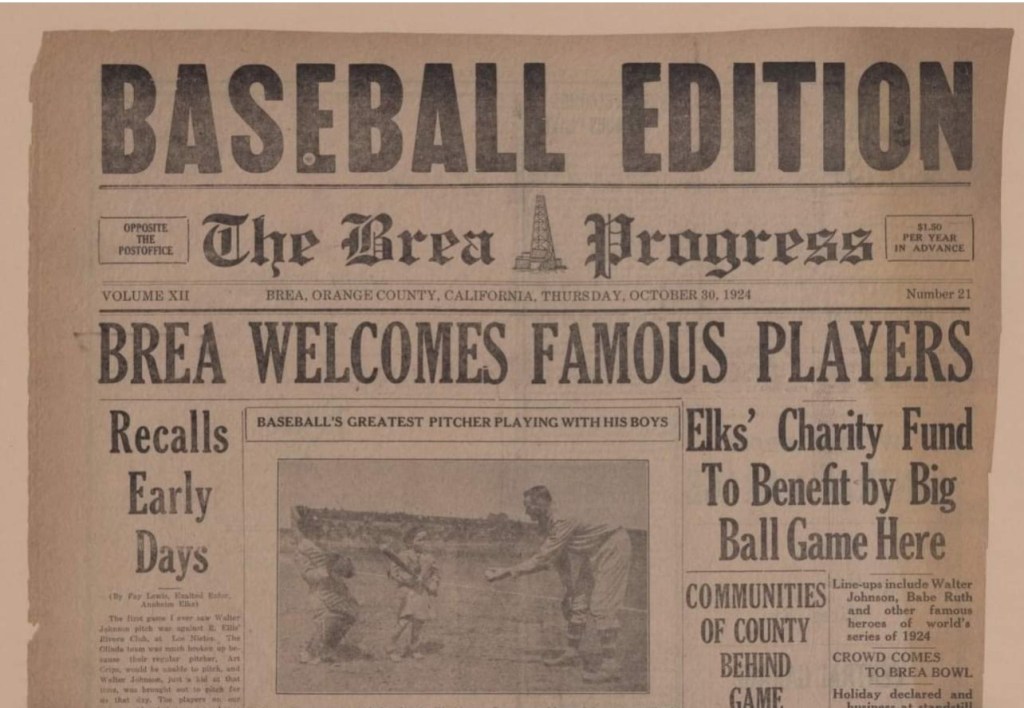

Johnson’s connection to Orange County was relived on Oct. 31, 1924 in Brea, three weeks after his Senators won the World Series. Johnson pitched against Babe Ruth as part of a barnstorming tour. Played at the Brea Bowl, some 5,000 fans showed up.

“The Big Train” was a member of the first five elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1936, three years before the building was completed in Cooperstown, N.Y. The group — Johnson, along with Ruth, Ty Cobb, Honus Wagner and Christy Mathewson — were also known as the “Five Immortals.”

When the Fullerton Flyers of the independent Golden Baseball League started play in 2005, it honored local baseball heroes by creating a bobblehead for Johnson — and giving him the number “05” as a way to mark the year. The min0r-league team lasted one more season with that name and became the Orange County Flyers through 2010.

Johnson, part of the Fullerton Union High School Walk of Fame, is also the namesake of Walter Johnson High School in Bethesa, Maryland. It was named in his honor for all he did with the nearby Washington Senators, but also, as Johnson got into politics while living in Maryland in the 1930s, he ran for the U.S. Congress in 1940.

We also have:

Kenny Brunner, Dominguez High of Compton basketball (1994 to 1997): Considered to be one of the nation’s top point guards, his team went 123-14 during his career.

Dick Barnett, Los Angeles Lakers forward (1962-63 to 1964-65)

Boogie Ellis, USC men’s basketball (2021-22 to 2023-24)

Jordan Farmar, Los Angeles Lakers guard (2006-07 to 2008-09): Best known wearing No. 1 in 2009-10 and 2013-14)

Carlos Boozer, Los Angeles Lakers forward (2014-15)

Jim Lefebvre, Los Angeles Dodgers second baseman (1965 to 1972)

Harry Howell, Los Angeles Kings defenseman (1970-71 to 1972-73)

Larry Murphy, Los Angeles Kings defenseman (1980-81 to 1983-84)

Bob Murdoch, Los Angeles Kings defenseman (1973-74 to 1978-79)

Mickey Rivers, California Angels outfielder (1971 to 1973): Also wore No. 3 in 1970 and No. 17 from 1974 to ’75)

Wally Joyner, Anaheim Angels first baseman (2001). Best known wearing No. 21 from 1986 to 1991.

Anyone else worth nominating?

Excellent content. Who knew #5 was so decorated. Thanks for including fellow Titan Mark Collins and co-Fullerton High alum Walter Johnson (although the Big Train and I did not have any classes together).

LikeLike