This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 11:

= Anze Kopitar: Los Angeles Kings

= Matt Leinart: Mater Dei High football, USC football

= Pat Haden: Los Angeles Rams

= Jim Everett: Los Angeles Rams

= Jim Fergosi: Los Angeles/California Angels

= Manny Mota: Los Angeles Dodgers

= George Best: Los Angeles Aztecs

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 11:

= Don Barksdale: UCLA basketball

= Bill Sharman: USC basketball

= Norm Van Brocklin: Los Angeles Rams

= Dwight Anderson, USC basketball

The most interesting story for No. 11:

John Elway: Granada Hills High football quarterback and baseball pitcher (1977 to 1979)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Granada Hills; Northridge; Dodger Stadium

John Elway’s 16-year NFL career, all with the Denver Broncos (1983 to 1998): Back-to-back Super Bowl wins to close out the 20th Century and his playing days, including the game MVP Award in the final contest he played; 47 fourth-quarter comebacks; 300 touchdown passes; 51,475 yards passing (second all-time upon his retirement) and going into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in his first year eligible of 2004.

Elway’s four-year college career, all at Stanford (1979 to 1982): Two-time Pac-10 player of the year, second in the Heisman voting as a senior, career passing leader with 9,349 yards and 77 touchdowns, No. 33 in ESPN’s list of the greatest 150 college football players in the game’s first 150 years, and No. 1 overall NFL Draft pick.

But what best sums up the high school legend of John Elway at Granada Hills?

“Oh, John, you are God’s gift to womanhood. You are the perfect specimen.”

Elway admitted to a Valley News of Van Nuys reporter in the fall of 1977 that some girl at school gave him that note in the hall, and then ran off before he could figure out who sent it. Elway, who had come to Granada Hills a year earlier as a sophomore, was still a bit shy and feeling his way around Southern California.

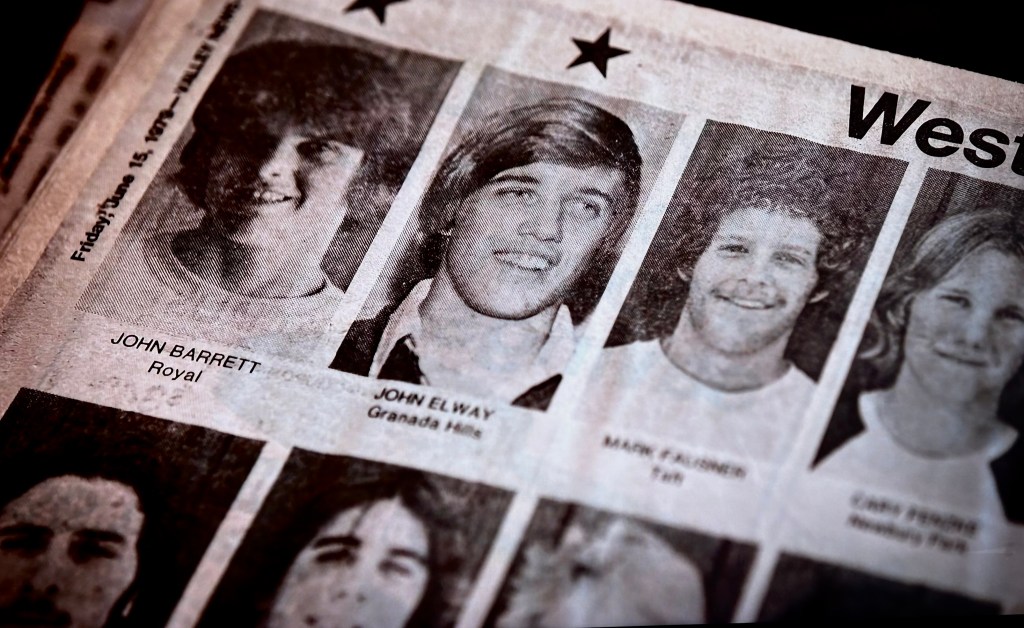

Before he made No. 7 somewhat his identity in college and the NFL, there was a vintage No. 11 Elway, both in football and baseball, who upon graduation was the focus of a Valley News story in its June 30, 1979 edition with the headline: “Is Elway best Valley athlete of all time?”

The questions still comes up in conversation 40 years later.

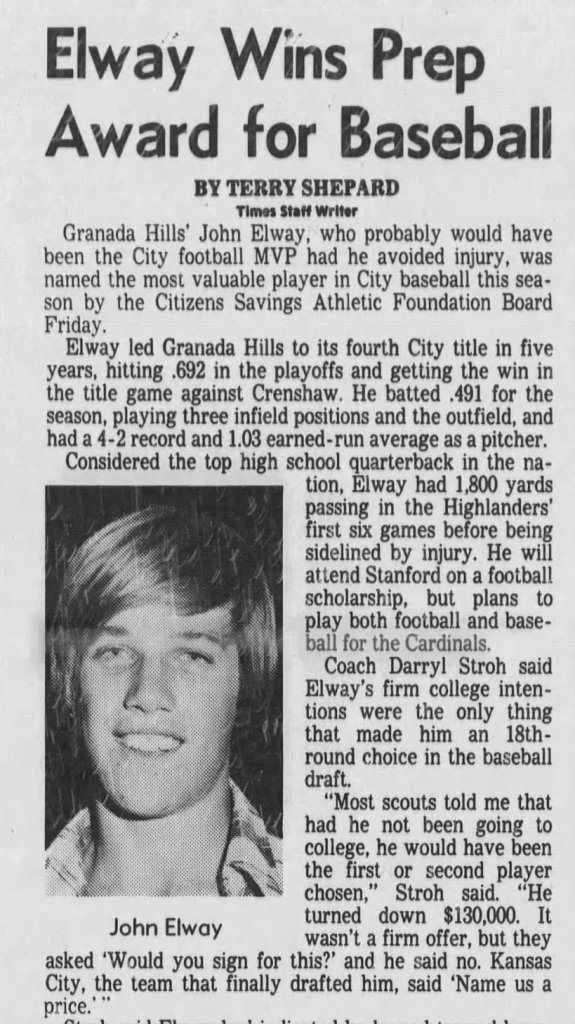

He didn’t win an MVP as a high school senior in football. His trophy came in baseball.

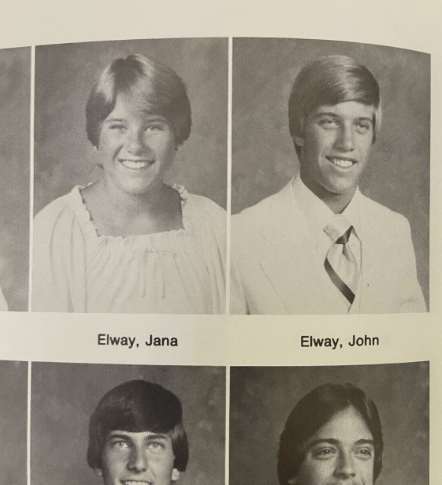

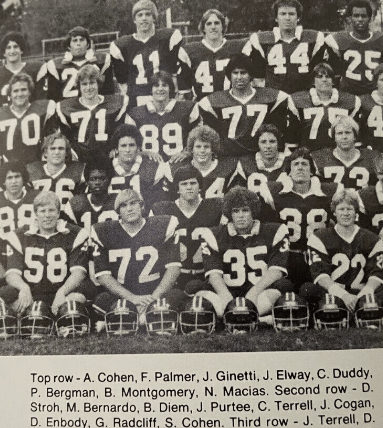

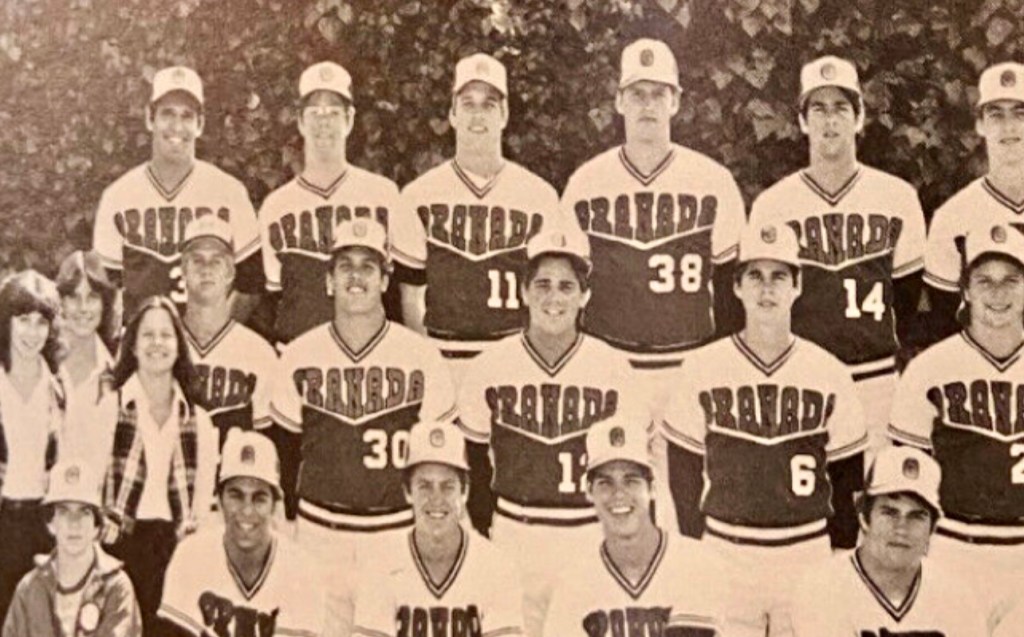

Elway’s Granada Hills High School senior class yearbook –the 1979 Tartan — has action shots of Elway playing football, basketball and baseball. There’s also the senior photo section, with John in his white suit and striped tie and large smile, next to his twin sister, Jana. Alphabetically, she came first.

They were actually considered “old” seniors,” born in late June, turning 19 right after that graduation. To all others in the high school athletic world of Southern California, maybe that didn’t seem quite fair.

In Elway’s high school yearbook from his junior year in 1978, with Jana again, next to him in their class shots, less dressed up and more “Fast Times at Ridgemont High” mode.

A classic shot of Elway in a football team photo shows him laughing out loud.

When you’re the son of a nomadic college football coach — John’s dad, Jack, brought the family to Northridge for a three-year run as the program’s head coach after he was a quarterbacks coach at Washington State — the fact you got to have three years at one school in Southern California was seen as something of a lucky break. Even when Jack left Northridge to take the head job at San Jose State in 1979, John stayed back to finish his high school at Granada Hills.

John Elway would consider going to nearby USC for college, but he gravitated to Stanford. He’d become the 1983 No. 1 overall draft pick of the NFL’s Baltimore Colts in a quarterback-rich field, nudge a trade to the Denver Broncos, and become one of the game’s legendary figures.

“John Elway was one of the single greatest athletes who ever lived,” says Adam Schefter, the ESPN NFL reporter, near the end of a 2025 Netflix documentary, “Elway,” that takes viewers through his life from high school to the Hall of Fame.

A 2004 Pro Football Hall of Fame inductee is celebrated as the only player in NFL history to pass for more than 3,000 yards and rush for more than 200 yards in the same season seven consecutive times. He is the second QB to record more than 40,000 yards passing and 3,000 yards rushing during his career.

He even got to play for his dad, who was as Stanford’s head coach starting in 1984.

But that time in Granada Hills … That’s when Elway cranked it up to 11.

The pitch

In 2021, when longtime Los Angeles Daily News and Los Angeles Times high school reporter Eric Sondheimer compiled a list of the 13 greatest athletes he had covered during his career going back to the early 1980s, No. 1 was John Elway.

Sondheimer told us how he came to that choice over the likes of Giancarlo Stanton, Bret Saberhagen, Russell White, Quincy Watts, Allyson Felix, Marian Jones, Cheryl Miller or even Tiger Woods: “John Elway’s arm strength as a teenager was, and is, second to none. He threw spirals with more velocity and farther than anyone I’ve seen. His athleticism was clear in the way he could scramble and in baseball, where he was equally effective as a hitter and pitcher. His leadership was so impressive that anyone would follow him.”

Sondheimer was a L.A. Poly High grad moving onto Cal State Northridge as a journalism student, a stringer covering high school sports, the same year that Elway family moved into town. The Elway relocation plan came after father Jack was let go as the offensive coordinator at Washington State, after aligning himself to be next head coach. That led to John starting his high school career as a freshman at Pullman High in Pullman, Wash. The team’s offense was run-first plan of attack. John Elway’s talents weren’t of much use.

Jack Elway saw what was going on at Granada Hills and how coach Jack Neumeier could play into John’s strengths with a pass-happy, run-and-shoot offense. It gave the quarterback the ability to change the play at the line of scrimmage depending on what he saw from the defense.

In the 2020 book, “Elway: A Relentless Life,” writer Jason Cole quoted John Elway: “I had more freedom in my high school system than I had the first 10 years of my NFL career. … It was fun. I was making decisions, I was learning the game. It was challenging and I could finally just do something back there. Everything just opened up.”

Cole interviewed Paul Bergman, a tight end on the Granada Hills team who wanted to play quarterback.

“He was scrawny, knock-kneed, pigeon-toed, just not a threat,” said Bergman, sizing up the competition at the position.

Then Elway threw the ball.

“I swear to you, I think the balls were rockets,” said Bergman, who became was a All-League, All-Valley, All-L.A. City receiver and linebacker at Granada Hills, caught nine passes and touchdowns from Elway at the East-West Shrine game, and set records as a tight end at UCLA. “You could hear the ball whistle when he threw. By the end of practice, I was over working with the receivers.”

In 1998, to coincide with Granada Hills High celebrating John Elway Day, Sondheimer made his own list of Elway’s high school athletic achievements, in chronological order.

Here they are, with our additional information:

Sept. 24, 1976: Elway made his high-school debut as a sophomore quarterback in a 13-0 loss to El Camino Real. He completed four of 10 passes for 41 yards. He had a pass intercepted on fourth and goal from the El Camino Real 7 yard line in the fourth quarter.

Granada Hills started the season 3-4-1, unsure about which quarterback to use. Elway grew five inches between his sophomore and junior year, suffering Osgood-Schlatter disease, with his knees in constant pain.

Sept. 23, 1977: Elway launched into his junior year showing off the first sign of his fourth-quarter magic. Trailing Carson, 16-0 a halftime, Elway rallied the Highlanders to a 19-16 victory when he connected with Jim Ginnetti on a 15-yard touchdown pass with 1:55 left. Elway threw for 256 yards and three touchdowns, going 12 of 15 for 144 yards in the second half.

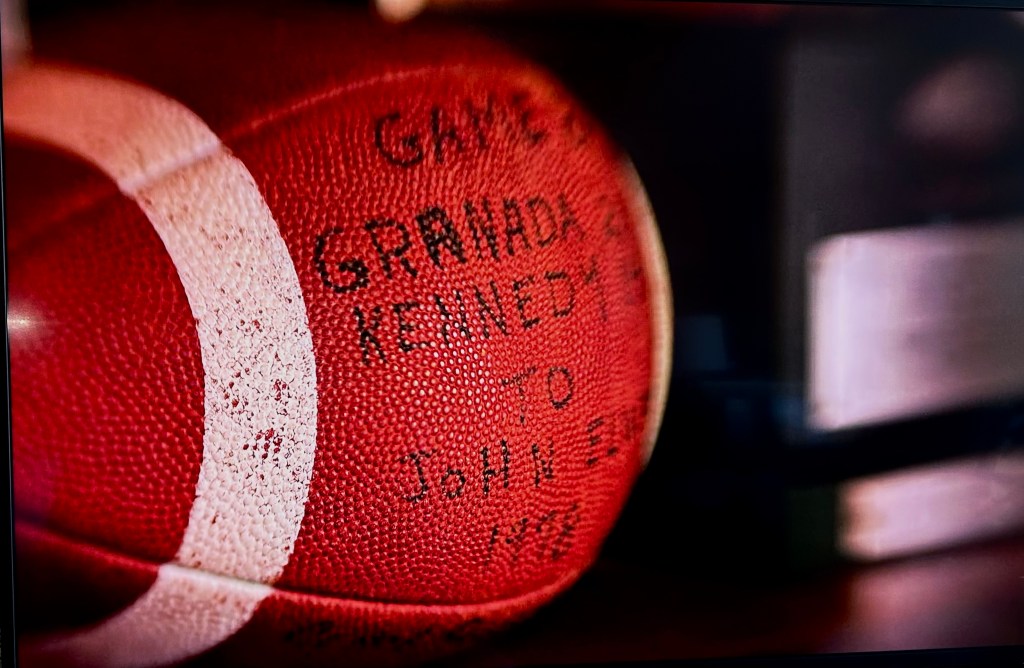

Oct. 21, 1977: It was Elway vs. Tom Ramsey of Kennedy High in this rivalry game. Seven Kennedy starters were suspended for spray-painting buildings at Granada Hills. Elway took advantage, completed 15 of 25 passes for 234 yards and two touchdowns in a 28-13 Highlander victory.

Some of the things the Kennedy High players spray painted on the Granada Hills High campus was “Elway sucks!”

Nov. 4, 1977: This is the game that made Elway a high school legend. Facing powerful San Fernando and its wishbone attack, Elway passed for 454 yards and four touchdowns in a 40-35 homecoming victory. He threw a 24-yard touchdown pass to Chris Sutton with 13 seconds left just moments after a nine-yard touchdown pass to Sutton was nullified because of a holding penalty. He moved Granada Hills 68 yards in seven plays in the final 1:32.

More than 9,000 were in attendance in this home game. The game-winning pass to Sutton was tipped by a San Fernando defender before Sutton caught it. That pushed Granada Hills onto a 5-0 record in league play heading into the City playoffs. Granada Hills got past Taft in the first round.

Dec. 2, 1977: Two future Super Bowl quarterbacks — Elway and Jay Schroeder of Palisades — locked up in a City Section quarterfinal playoff game decided by a new California tiebreaker. The ball started at the 50-yard line. The team that advanced the ball farthest on alternating plays would win. As the game finished 27-27, the teams reached the seventh play of an eight-play tiebreaker when Elway completed a 28-yard pass to receiver Scott Marshall to clinch a 28-27 Granada Hills victory. Also starting for Palisades High at defensive left tackle: Future Academy Award winner Forest Whitaker.

Granada Hills lost to Banning, 38-6, in the City semifinals as Elway completed 18 of 36 passing for just 170 yards.

Sept. 22, 1978: During a 40-28 loss to Carson High, Elway completed a 64-yard touchdown pass to Steve McLaughlin that traveled 70 yards through the air. Coach Neumeier insisted: “Not even in the pros could they do that.” Elway passed for 479 yards.

Oct. 28, 1978: Against San Fernando in another Mid-Valley League showdown, Elway scrambled for a nine-yard gain in the second quarter, then came up limping. He returned in the second half after wrapping his left knee, but the Highlanders lost, 21-10. It was Elway’s final football game for the Highlanders. His season ended because of knee surgery for torn cartilage.

The Highlanders season ended in a heartbreaking 20-19 overtime loss to Carson in the City 4-A semifinals.

July 21, 1979: In his final prep football appearance, Elway completed 23 of 37 passes for 363 yards and four touchdowns to lead the North past the South, 35-15, in the Shrine All-Star game at the Rose Bowl. USC head coach John Robinson, who lost a recruiting battle to Stanford, said of Elway as he was in the TV booth as a color commentator: “He’s the best ever to come out of high school.”

In the spring of 1978, Granada Hills won the L.A. City baseball championship — Elway was named the City Player of the Year.

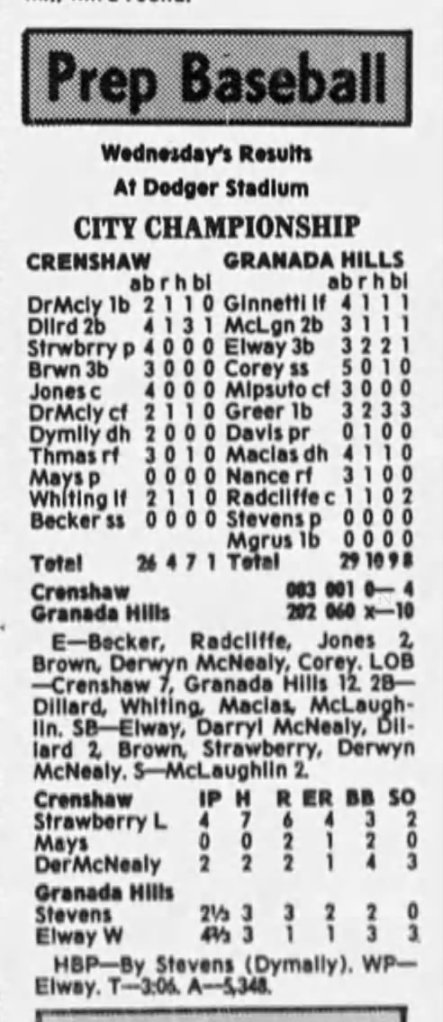

A year later, Granada Hills is unexpectedly back in the title game against top-seeded Crenshaw, led by heralded super junior Darryl Strawberry.

Elway was the only returning starter on this ’79 team for Granada Hills, and the team started 1-6. During a game midway through the season, Elway wasn’t faring well as a pitcher, hitting two batters and walking five. Coach Darryl Stroh took him out, told him to go to third base, and his pitching days were done. Which was fine by his dad, Jack, as John was really priming to go to Stanford for football.

Granada Hills somehow won eight in a row to qualify for the City playoffs as the third team out of the Mid-Valley League. Elway went 4-for-5 with a double and six RBIs in Granada Hills’ 20-14 win over South Gate in the City semifinals at West L.A. College, pushing them to the title game for the fourth time in five years.

The Crenshaw team, with future MLB player Chris Brown along with Strawberry, scored 33 runs in three playoff games, overcoming a 5-1 deficit to defeat Monroe, 10-7, in their City semifinal game leading to the title faceoff at Dodger Stadium on June 6 before some 20,000 fans. Both teams were 13-5.

Granada Hills took a 2-0 lead in the bottom of the first when Elway singled off Crenshaw starting pitcher Strawberry to bring home Jim Ginnetti. Elway stole second and scored on Dony Green’s single.

Crenshaw erased the deficit with three runs in the top of the third. As Stroh went to the mound, he decided: Elway, come in from third base and get us out of this mess.

“As I was walking out there, it just came to me: I have to go with the toughest guy I know,” Stroh is quoted in “Elway: A Relentless Life.” “We’re in a fight … when you go to war, you take your biggest gun. The attitude John had, the competitiveness, the determination … John sort of had his back turned to me because I think he knew I was going to call on him. Deep down inside, I bet he loved it.”

Elway later told Sondheimer: “It’s probably my best baseball story. I was horrible. I didn’t pitch for [one month] before that game. I had this funny feeling as he walked to the mound that he’s going to give me the ball. I wanted to hide. I didn’t want to be pitching because the last time I was so bad.”

Teammate Jim Ginnetti — the receiver Elway connected with to secure the late win over Carson in September of ’77 — said of Elway in that baseball moment: “He looked at me and said, ‘We ain’t losing this game’.”

Elway struck out the first batter to get out of the jam.

In the bottom of the third, Elway led off with a single off Strawberry and moved to third on a walk and error that loaded the bases. Keith Nance’s grounder went through Crenshaw first baseman Darryl McNealy’s legs for two runs.

With the 3-2 lead, Crenshaw threatened to blow it open against Elway in the fifth inning. A hit and a walk put two on with no one out, and Strawberry came to the plate. Strawberry flew out to the warning track in left field in his previous at bat. Crenshaw’s coach, Brooks Hurst, decided to play the percentages and asked Strawberry to bunt the runners over.

Yes, bunt.

Strawberry bunted all right — right back to Elway, who pounced on it off the mound and threw to third for the force. Crenshaw then tried a double steal, but catcher Greg Radcliffe threw out the runner going to third. Elway finished the inning with a strikeout.

Strawberry walked a few in the bottom of the fifth and with errors behind him, the Cougars gave up six runs on just three hits. Elway would be the winning pitcher in the 10-4 victory, pitching 4 2/3 innings of relief. Strawberry took the loss, giving up four earned runs (six overall) in four innings.

Elway was named most valuable player of the tournament after for collecting nine hits in 13 at-bats — and then found out he was an 18th round by the Kansas City Royals.

Elway was the only player from Granada Hills named to the All-City team — picked as a utility player for hitting .491 and having a 4-2 record as a pitcher. Palisades’ Jay Schroeder was first team as a catcher, hitting .523.

For the time being, Elway declined the pro baseball route.

Elway made it into the Stanford football field a month later, after the Shrine All-Star Game, and was allowed to play professional baseball in the Yankees’ farm system as they tried to coax him over as the second-round pick in the 1981 MLB Draft. That was a year after Strawberry was taken No. 1 overall by the New York Mets.

Elway signed, hit .318 in 42 games for the Single-A NY Penn League, but there would be no Elway-Strawberry rematch on the baseball diamond.

Makes on wonder how Strawberry would have been as a 6-foot-6 receiver doing over the middle, trying to handle an Elway fastball.

Photo gallery

From the 2025 Netflix documentary “Elway,” a collection of photos and videos are included covering his high school days:

The legacy

John Elway Stadium at 10535 Zelzah Avenue entering Granada Hills Charter High School seats 4,000 these days. Elway’s name attached to it became official in 1998, after Elway’s first Super Bowl win for Denver. A new $8,000 scoreboard was attached to it.

Elway told Sondheimer at the time it was special to have this happen because that school “put me on the map. It’s a special place in my heart because it’s where I started.”

Sondheimer added in his story:

When the history of the Valley in the 20th century is fully written, Elway’s name will be prominent not just because he’ll be an NFL Hall of Fame quarterback. People will remember his special qualities as a person.

He lived here only for his three high school years, but he has not forgotten the people who influenced his life during that time. He has returned to play in Granada Hills alumni baseball games, something unthinkable for most athletes of his stature. He does so to visit with former teammates and friends and to honor the man who helped mold his value system, longtime Granada Hills Coach Darryl Stroh.

Elway’s return to Granada Hills is more than a triumph of natural talent. There never has been a quarterback in this region that possessed Elway’s combination of a magical arm and unmatched leadership qualities. But sometimes forgotten is Elway’s intelligence. He planned for the future by studying hard and refused to let celebrity status change his outlook on life.

“There’s too many variables involved with sports to put all your eggs in one basket,” he said. “At some point, you’re going to have to rely on your education. One freak deal can end your athletic career, but you’re always going to have to fall back on your education. Sports is short term; education is long term.”

John Elway got to watch his own son, Jack, experience that process. Wearing No. 7 at Cherry Creek High in surburban Denver, Jack was enough of a prospect to draw the attention of Arizona State but decided football wasn’t for him any more and got a degree in economics.

To keep the learning process going for future Granada Hills students, there was an NFL celebration of past Super Bowl participants in 2016 that included a ceremony where a gold football honoring Elway and his roots was put on display. That coincided with the Denver Broncos returning to, and winning, Super Bowl 50 in Santa Clara. With Elway getting to hoist the Super Bowl Trophy, again, this time as the team’s general manager, responsible for bringing Peyton Manning onto the roster to lead the offense.

When the California High School Football Hall of Fame was announced in 2022 as a permanent display at the Rose Bowl, Elway was one of the 100 players chosen. The urge is to cut the list down to just SoCal prep phenoms and see if Elway would still top that subset.

Glenn Davis, from Bonita High in La Verne (who won a Heisman at Army) might be the one who stacks up closest as far as legendary status as all L.A. CIF in football and baseball — and he also had a twin sibling.

Bob Waterfield (Van Nuys), Pat Haden (Bishop Amat), Matt Barkley and Matt Leinart (Mater Dei), Carson Palmer (Santa Margarita High) and Frankie Albert (Glendale) are in the conversation, as the quarterbacks, with Anthony Davis and Charles White (San Fernand0), Russell White (Crespi) and Jackie Robinson (Muir). Elway’s somewhat abbreviated senior season takes away the chance at some legend in title games — so he made up for it in baseball.

At a time when Elway was in high school, aside from Ramsey, the area already had Tom Tunnicliffe at Burroughs, John Mazur at El Camino Real and Mike Owens at Van Nuys.

And by the way, still on eBay.com: A few vintage Nike John Elway 1979 Granada Hills High throwback jersey are available. In the $75 to $120 range.

Complete with name tag on the shirt front tail.

Whatever suits your nostalgia.

Who else wore No. 11 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

Anze Kopitar, Los Angeles Kings center (2006-07 to 2025-26):

Best known: A franchise records in seasons played (20), most games played (more than 200 better than anyone below him), game-winning goals (78), plus-minus (56.4) and total assists (topping 800). And most seasons as a team captain (10). Second in total points (just 30 short of leader Marcel Dionne, and closing in on the Top 50 NHL all-time list) and third in goals (440). There’s also hoisting two Stanley Cups, two Lady Byng Awards (for sportsmanship) and two Selke Awards (best defensive forward).

Robitallie? Dionne? Gretzky? Quick, make a case for Kopitar as a Los Angeles Times columnist tried to do, starting with the fact he knew no English coming over here from Slovenia and still achieved what he achieved.

Not well known: His nicknames include “Racoon Jesus.”

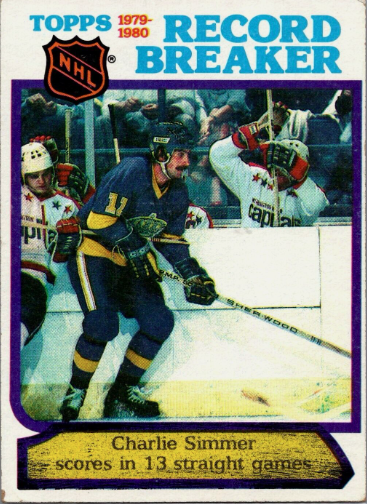

Charlie Simmer, Los Angeles Kings left wing (1978-79 to 1984-85):

Best known: Part of the famous Triple Crown line with Marcel Dionne and Dave Taylor, Simmer set a modern NHL record by scoring goals in 13 straight games from Nov. 24 to Dec. 30, 1979. He piled up 17 goals in that stretch. His seven-plus seasons in L.A. included two All Star Games, leading the NHL in goals with 56 in ’79-’80, and with 10 game-winning goals in 1980-’81. His 222 goals and 79 power-play goals are Top 10 on the franchise lists.

Not well known: Simmer wore No. 26 in 1977-78 after coming to the Kings from the Cleveland Barons — yes, an actual NHL team, as were the California Golden Seals, where Simmer played his first two NHL seasons.

Matt Leinart, USC football quarterback (2001 to 2005):

Best known: His 2017 College Football Hall of Fame bio starts: One of the greatest quarterbacks in college football history …, reflecting his 2004 Heisman Trophy as a junior, having already finished No. 6 in the voting as a sophomore and No. 3 in the voting as a senior. The former Mater Dei of Santa Ana standout set Pac-10 records for career (99) and single-season (38) touchdowns, career completion percentage (64.8) and consecutive passes without an interception (212). As USC won the 2003 and 2004 national titles and played for the crown in 2005, Leinart was MVP of the 2004 Rose Bowl and 2005 Orange Bowl. His No. 11 jersey was retired by the Trojans and he was inducted into the USC Athletics Hall of Fame in 2007.

Not well known: Leinart’s 1.85 percent interception ratio stood an NCAA-record, and his 94.9 winning percentage as a quarterback (37-2) is a school record and second-best in NCAA history (behind Boise State’s Kellen Moore and his 50-3 mark).

Norm Van Brocklin, Los Angeles Rams quarterback/punter (1952 to 1957):

Best known: In the Rams’ 1951 season opener, Van Brocklin threw for an NFL record 554 yards against the New York Yanks, completing 27 of 41 passes and five touchdowns, four them to Elroy “Crazylegs” Hirsch. That season ended with Van Brocklin throwing a 73-yard pass to Tom Fears that gave the Rams a 24-17 victory over the Cleveland Browns in the first NFL title the Rams had in Los Angeles. Part of the 1971 Football Hall of Fame class, Van Brocklin also 13 seasons as an NFL head coach in Minnesota and Atlanta.

Not well known: Van Brocklin wore No. 25 for his first three L.A. NFL seasons (1949 to 51) after leaving the University of Oregon early. In 1952, he switched to No. 11 as a way to indicate he was the primary starter after sharing the spot with the retired Bob Waterfield.

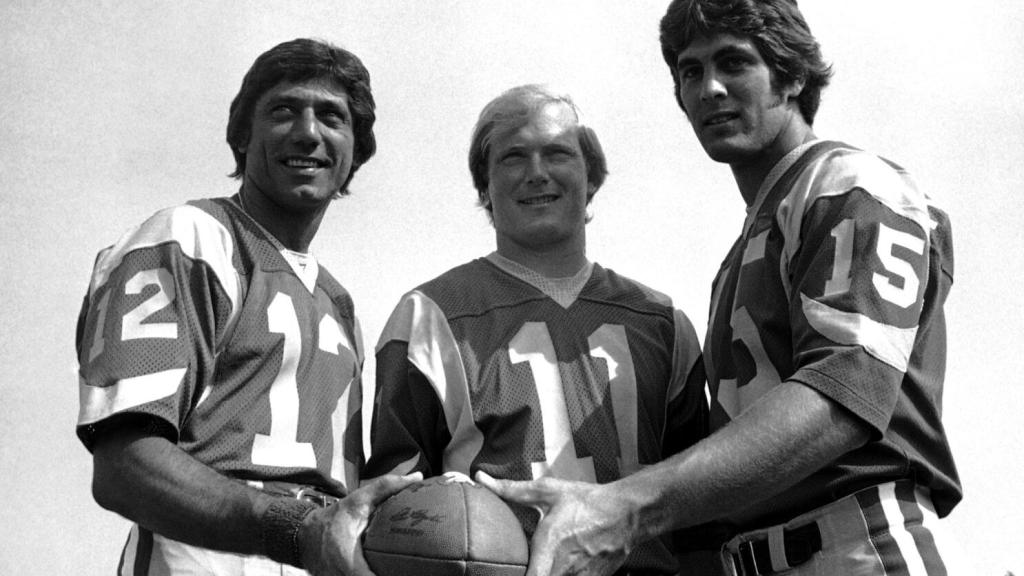

Pat Haden, Los Angeles Rams quarterback (1976 to 1981):

Best known: Two years after his standout career at USC, followed by a year chasing a paycheck with the World Football League’s Southern California Sun, Patrick Capper Haden did the Rhodes Scholar move and went to the Rams. He started all 16 games in ’78 (299-for-444, 2,995 yards, 13 TDs, 19 INTs) as the Rams went 12-4 in Ray Malavasi’s first year as head coach, winning the NFC West but losing to Dallas in the conference championship. Haden was voted the Washington D.C. Touchdown Club NFC Player of the Year for ’78. He started the first 10 games of the ’79 season before be broke a finger, yielding to backup Vince Ferragamo, who drove the Rams into the Super Bowl against Pittsburgh.

Not well known: Haden was third on the Rams QB depth chart in 1976 behind James Harris and Ron Jaworski when, as the story goes, team owner Carroll Rosenbloom ordered head coach Chuck Knox to start Haden. Even though Harris was the top-rated passer in the NFC. It gave Haden enough material to write a book about it and state his case. In 1977, with Harris and Jaworski traded away, Haden was still left behind by Knox, who tried to hand the starting job to a beaten-up Joe Namath. Haden came to the rescue after the first four games, navigating the team to an 8-2 mark, throwing for 1,551 yards and 11 touchdowns against six picks and drawing Pro Bowl recognition. Malavasi gave Haden the starting job back in 1980, but when Haden was injured in the opener, Ferragamo took over again. Haden came back to start 11 games in ’81, but gave way to Dan Pastorini and decided, at age 28, to take CBS up on a broadcasting analyst offer.

Jim Everett, Los Angeles Rams quarterback (1986 to 1973):

Best known: Everett led the team to three playoff runs, including the 1989 NFC championship game, and had a Pro Bowl season in 1990 when, at 27, he threw for 3,989 yards and 23 touchdowns despite the team’s 5-11 record. His eight-year run with the Rams produced a 46-59 win-loss record to go with 23,000 passing yards, 142 touchdowns and many instances of looking quite skittish as phantom rushing defensive players left him short of a first-down marker. That led to a 1994 meltdown on Jim Rome’s ESPN2 show after the host made a few references too many as to why Everett had been tagged with the nickname “Chris” (as in, women’s tennis player Chris Evert). As a result, Everett flipped the table on Rome and stood over him as the live camera cut away. At least Everett wasn’t sacked on the play.

Not well known: The Purdue quarterback was the third overall pick by Houston in 1986, but the Rams felt good enough about him to concocted a trade, sending Pro Bowl guard Kent Hill, defensive end William Fuller, and first-round picks in the next two drafts.

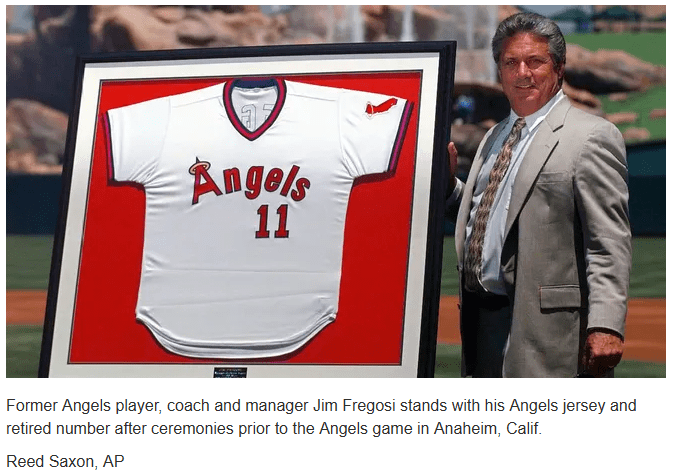

Jim Fregosi, Los Angeles/California Angels shortstop (1961 to 1971):

Best known: An original member of the expansion Los Angeles Angels, Fregosi had six AL All-Star appearances in seven seasons, finished as high as seventh in the AL MVP balloting and won a Gold Glove in 1967. He was then, at age 30, the key component in a 1972 trade with the New York Mets in exchange for pitcher Nolan Ryan.

Not well known: Fregosi came back at the Angels manager from 1978 to 1981 to please owner Gene Autry. The hire happened just a month after his playing days ended in Pittsburgh. He would wear No. 11 again as it wasn’t retired in his honor yet.

Manny Mota, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder/pinch hitter (1969 to 1982):

Best known: A .315 average for the Dodgers in 13 seasons, including a 1973 All-Star Game appearance, made him a fan favorite — you can hear his name echoing through Dodger Stadium as the public address announcer does his best John Ramsay imitation during the 1988 movie “The Naked Gun: Files from the Police Squad.” Mota came out of retirement in 1982 for one more at-bat at age 44 and left the sport as the all-time leader in pinch hits with 150. A Dodgers coach from 1980 through 2013 – the longest term in team history – he was added to the “Legends of Dodger Baseball” category in 2023.

Not well known: In 1977, Mota went 15 for 50 (.395) in 49 games, with 10 walks, two sacrifice bunts and not one strikeout.

Also not well known: On May 16, 1970, Mota, hitting against San Francisco’s Gaylord Perry in the bottom of the third inning, lined a foul ball over the first-base dugout. It hit a 14-year-old fan, Alan Fish, in the temple. Fish initially seemed fine, received first aid at the stadium, but later became disoriented and died four days later from a skull fracture and intracerebral hemorrhage. “I felt guilty because I hit the foul ball and a young boy lost his life,” said Mota. It was the first time a spectator died from a foul ball in Major League Baseball history.

Don Barksdale, UCLA basketball guard (1942-43 to 1946-47):

Best known: The first African American All-American player in NCAA basketball history joined the Bruins in March of ’43 from Marin Junior College — some considered him a bit of a ringer that late in the season — and he was named the top center in the Pacific Coast Conference Southern Division after playing just five games. Barksdale arrived at UCLA at a point in time when USC had won 42 straight games over the Bruins, spanning 11 years. Barksdale had 18 points in a 42-37 win over the Trojans on March 5. He then took two years off in the Army before coming back for his final All-American season. His No. 11 was retired in 2013.

Not well known: Barksdale was also the first African-American to win an Olympic gold medal in 1948 before becoming one of the first African-Americans in the NBA in 1951.

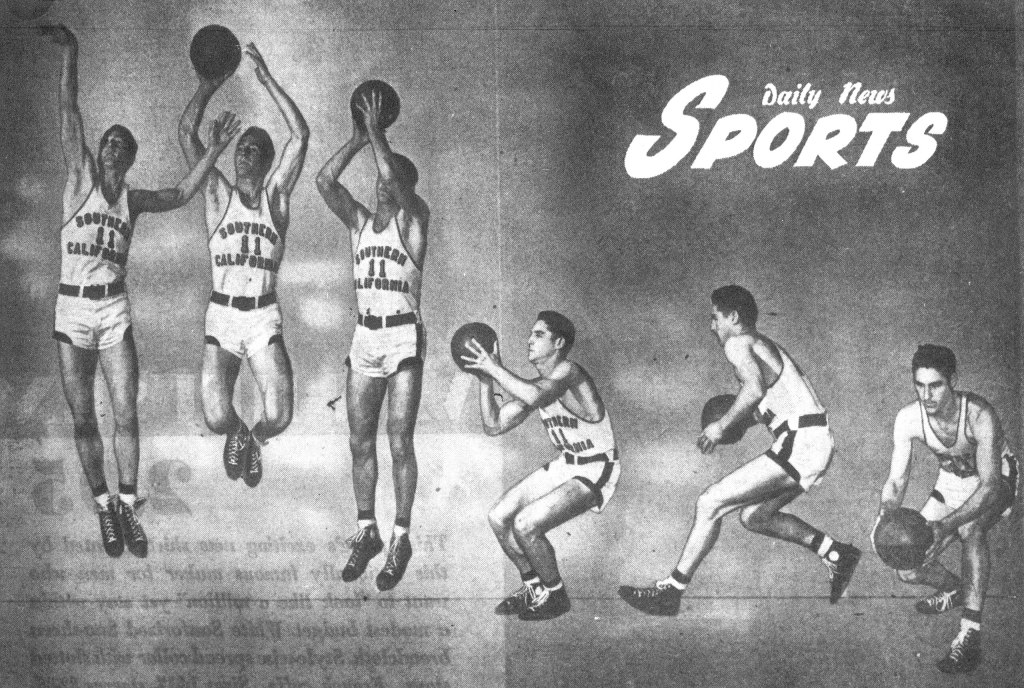

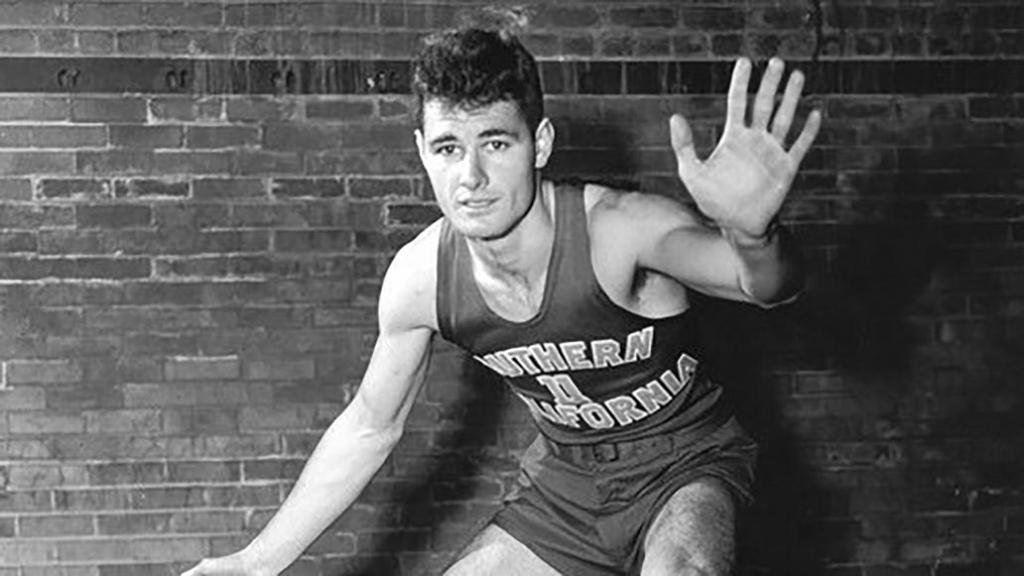

Bill Sharman, USC basketball guard (1946-47 to 1949-50):

Best known: The Pacific Coast Conference’s Most Valuable Player in both his junior and senior seasons, and an NCAA All-American in 1950, “Bullseye Bill” averaged 13.8 points in his 82 games on the Trojans’ basketball team. Growing up in Lomita and a freshman at Narbonne High in Harbor City, his family moved to Porterville in Northern California where he was awarded 15 letters in basketball, baseball, track and tennis, the later of which he won a state title, before he came back to Southern California.

Not well known: Sharman played first base on the 1948 USC Trojans’ College World Series championship team and spent five years in the Brooklyn Dodgers’ organization with a brief callup in ’51 that would overlap with the start of his 11-year NBA career with the Boston Celtics. Sharman is in the Basketball Hall of Fame as both a player and coach and was included in the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History team in 1996 and the NBA’s 75th Anniversary Team in 2021. That is in addition to a 15-year coaching career where he won titles in the NBL, ABA and NBA – the later with the Lakers in 1971-72.

Fred “Tex” Winter, USC basketball guard (1946-47):

Best known: Winter earned his Basketball Hall of Fame credentials as a head college coach and as an assistant NBA coach – more specifically, refining the Triangle/Triple Post Offense that Phil Jackson implemented in Chicago and with the Lakers (2000 to ’09). The seeds were planted when Winter was voted the Trojans’ Most Inspirational Player the only season he played. His USC coach, Sam Barry, actually created the genesis of the Triangle Offense with something he called the Center Opposite alignment. Winter was inducted into the USC Athletic Hall of Fame in 2003, eight years before the Naismith Hall honor.

Not well known: Winter was a top pole vaulter when he lettered in track and field in 1946 out of Huntington Park High and Compton College.

Karl Malone, Los Angeles Lakers forward (2003-04):

Since the 14-time All Star never won an NBA title with the Utah Jazz, he dedicated his 19th and final season chasing one with the Lakers as a 40-year-old with faulty knees, having to forgo his usual No. 32 and take on the slimming No. 11. He lasted just half the regular season and he mailed it in with a career-low 13.2 points and 8.7 rebounds — dandy, if your name was Mel Counts. But Malone counted on more than just a Pacific Division title and a short-lived sports-talk show in L.A. that fed into a loss to Detroit in the NBA Final, along with mercenary teammate Gary Payton. Then it was off the Basketball Hall.

Bob McAdoo, Los Angeles Lakers center (1981-82 to 1984-85): The seven-time NBA All Star and three-time NBA scoring champion broke free from the Eastern Conference to become a first-off-the-bench Showtime Laker as part of the 1982 and 1985 title teams. Then it was off to the Basketball Hall.

Paula McGee, USC women’s basketball forward (1980 to 1984): With twin sister Pam McGee, Paula was part of the 1983 and ’84 NCAA championship squads, a four-time All-WCAA first team member, and had her number retired. She averaged 20.0 points and 9.2 rebounds per game as a freshman and left as the program’s fourth all-time leading scorer (2,346 points).

Tim Green, USC football quarterback (1983 to 1984): The defiant, surf-crazed left-hander out of Aviation High in Manhattan Beach shared the 1985 Rose Bowl MVP with teammate Jack Del Rio after a 20-17 over Ohio State. Green threw for just 1,320 yards and three TDs against eight interceptions in the regular season, but led the team in place of the injured Sean Salisbury to seven straight wins. He completed 13 of 24 passes for 128 yards and two touchdowns against the Buckeyes. Green spent his first two years eligible at El Camino College, setting 12 national junior college records at quarterback while passing for 5,448 yards and 49 touchdowns.

Jacque Vaughn, Muir High of Pasadena (1989 to 1993): The “Prince of Positivity” averaged 21 points and 19 assists a game as a senior along with a 3.9 GPA to be a first-team All-American pick and win MVP honors in the McDonald’s All-American game. That vaulted him to having his No. 11 retired at the University of Kansas, followed by 12 years in the NBA. Vaughn was the first to have his No. 11 retired by Muir, along with Stacey Augmon (32), Eric McWilliams (33) and Tye’sha Fluker (50).

Have you heard these stories:

George Best, NASL Los Angeles Aztecs midfielder (1976 to 1978):

Best known: His decision to leave England and remove himself from a barrage of media that led to a mental breakdown meant he could log 55 games with the North American Soccer League’s L.A. Aztecs, scoring 27 goals and adding 25 assists. It was said that he was actually doing it as a favor to Aztecs co-owner Elton John.

In the 2025 book, “The Soccer 100: The Story of the Greatest Players in History,” Best is ranked No. 15 all time, having won the Bailon d’Oro in 1968, the same year he won the European Cup and scored in the final for Manchester United. Once called the “best player in the world” by Pele, Best can best be explained in the 2016 documentary “All By Himself.” His death in 2005 at age 59 was not unexpected – he and his manager operated Bestie’s Beach Club in Hermosa Beach in the 1970s, a watering hole created so he could hang out at and not have to worry about paying all the mounting beer tabs to other taverns in the South Bay.

Not well known: A scene in the 2017 movie “T2 Trainspotting,” the sequel to the original 20 years earlier, Ewan McGregor, Kelly Macdonald and Johnny Lee Miller are reliving a well-told urban legend about Best that leads into the question: Where did it all go wrong?

Chase Griffith, UCLA quarterback (2019 to 2024):

Best known: The 2023 and ’24 Arthur Ashe Sports Scholar of the Year and regular UCLA Honor Roll member procured a undergrad degree in public affairs and master’s in the transformative coaching and leadership program. That led to him being recognized as a two-time National NIL Male Athlete of the Year. As his LinkedIn account explains, his interest in college athlete empowerment, investing, wealth building and public service. He has also incorporated his No. 11 into a branding tool and the name of his social media company. Bloomberg called him the “undisputed king of college endorsement deals.”

Born in Santa Monica, Griffin was a 13-year-old eighth-grader in Round Rock, Tex., in 2014 when he was labeled a “prodigy” in an ESPN story about “The QB Most Likely to Succeed.” It said Griffin was “a 99th-percentile test-taker and chamber orchestra violinist who’s already plotting to one day run a water purification startup, then maybe run for president. But he’d rather be a quarterback. He threw for 4,051 passing yards and 51 TD as a senior, ran 415 yards and eight touchdowns and was named Texas Gatorade Player of the Year. He turned down five Ivy League schools to attend UCLA.

In January of 2024, Griffin testified before Congress on Capitol Hill about proposed legislation to regulate NIL within the NCAA. “I always appreciate people who recognize that I do work hard in the space,” Griffin told The Washington Post after the hearing. “But at the same time, I hope that when they recognize me, they realize they are recognizing the majority of college athletes who are partaking in NIL right now. . . . When you say that I’m the poster child of what college athletes should be doing, no, I’m just another example of what college athletes are already doing. And when you look at what I’m doing and say, ‘This is what’s right with NIL,’ no, you’re saying, ‘NIL is what’s right with NIL.’ ” He also told the Daily Bruin: “We have a system that allows me free reign over how I go about my NIL, which I really appreciate. I’m excited to see as we transition to the Big Ten, how we can remain true to ourselves, hopefully continue building on programs that can help other athletes … go about NIL in their best way.”

Not well remembered: Griffin’s UCLA career totals: Nine games, throwing 41 of 67 for six TDs and two interceptions, and running 43 yards on 20 carries. After he redshirt in 2019, Griffin was moved in as a starter in 2020 for four games due to injuries/illness for Dorian Thompson-Robinson. In the season finale, Griffin completed 9 of 11 passes for four touchdowns against Stanford in a 48–47 loss in double overtime loss. He sat out 2021 for COVID, returned for two games in ’22 and three in ’23. Again a redshirt senior on the ’24 roster, Griffin didn’t play, effectively ending his career at UCLA.

Dwight Anderson, USC basketball guard (1980-81 to 1981-82):

Best known: In early March 1982, during a USC basketball game at the L.A. Sports Arena against Washington, the 6-foot-1 guard known as “Flash” shot and made a basket from the behind the backboard as he was sailing out of bounds. On the TV telecast, Dick Enberg was speechless, and Al McGuire exclaimed, “A star is born!” A 2011 documentary called “The Blur” includes that play — the outlet pass was from USC’s James McDonald (who would go onto play tight end in the NFL with the Los Angeles Rams). USC coach Stan Morrison called it “the greatest shot ever made.”

Not well known: Anderson died in 2020 at age 59, battling from all sorts of addictions. He transferred to USC from Kentucky midway through the 1980 season, having left the Wildcats program with a cocaine addiction. He became eligible for the Trojans in the second half of the 1981 season. In 1982, he led USC with a then-school career scoring average record of 20.0 points per game and helped lead USC to a 19-9 record and into the NCAA Tournament.

Frank Selvy, Los Angeles Lakers guard (1960-61 to 1963-64):

Best known: As the starting guard on a brand new L.A. Lakers team that featured Elgin Baylor, Jerry West, Rudy LaRusso and Hot Rod Hudley, Selvy did something years before none of them ever did: Score 100 points in a game. It set an NCAA Division I single-game record when he played at Furman University in 1954 — eight years before Wilt Chamberlain scored 100 in an NBA game for the professional record. In the New York Times obituary for Selvy, who died at 91 in August of 2024, it noted that he was an NBA All-Star for the Lakers in 1962, when he averaged 14.7 points a game. “But that season ended on a sour note for the Lakers and especially for Selvy.” The Lakers and Boston Celtics were tied at 100 each at Boston Garden with five seconds remaining in the fourth quarter of the decisive Game 7 of the NBA championship series. Selvy had hit two baskets in the previous 20 seconds to tie the game. Selvy inbounded the ball to Hundley, brought the ball up the floor, fakes a pass to West, then found Selvy alone in the left corner. Selvy shot the 18-footer — it hit the rim and missed. Selvy thought he was fouled by Bob Cousy. Had the shot went in, it would have given the Lakers the title, the first since moving to L.A. two years earlier. The Celtics’ Bill Russell got the rebounds, Boston won, 110-107, in overtime. The Lakers wouldn’t beat the Celtics in an NBA Final until 23 years later.

Not well known: Franklin Delano Selvy was named because he was born in November of 1932 in Corbin, Kentucky on the day that Franklin Delano Roosevelt was declared winner of the U.S. presidential election. Also: Selvy was issued No. 11 when he first joined the Minneapolis Lakers in 1957-58 (the season he scored his pro career-highs of 42 and 40 points in a game), then switched to No. 70 when he came back to the team in ’59-’60, and then went back to No. 11 when the team moved to Los Angeles.

Penny Toller, Los Angeles Sparks guard (1997 to 1999):

Best known: The Long Beach State graduate, whose No. 4 was retired by the school, became the fist female athlete to have her number put up on the wall at Staples Center — ahead of teammate Lisa Leslie. Toller could only play professionally overseas after college, so eight years went by before the WNBA opportunity came available. She ended up scoring the first basket in league history on June 21, 1997 at the Forum in Inglewood. “I didn’t even realize it,” she would say. “It was after the game when all the reporters said, ‘How does it feel to score the first basket in WNBA history?’ … as a player, I was thinking at that moment, ‘Wow, we lost the game at home.’”

Not well remembered: Toller started 58 games in a row for those first two Sparks seasons, and eventually became the team’s general manager, keeping that role for 18 years. She also was the team’s interim coach in 2014.

Mario Mendoza, California Angels minor-league hitting instructor and manager (1992 to 2000):

Best known: “The Mendoza Line” was a phrase created by Kansas City Royals’ star George Brett as the cut-off point in the long list of MLB batting averages that showed in the Sunday newspaper. No one, said Brett, wanted to hit below whatever Mario Mendoza was hitting. In nine MLB seasons with Pittsburgh, Seattle and Texas from 1974 to 1982, Mendoza had a minus-2.6 WAR with a .215 batting average.

Not well remembered: The Angels brought him as a minor-league hitting instructor before naming him its Single-A manager in Palm Springs. “When I first game to the Angels, fans would come down and give me a hard time about (his MLB career),” Mendoza told The Athletic in 2020. “And when sportswriters wanted to talk about it, I said, ‘No, if you want to talk about other stuff, then we can talk about the Mendoza Line.’ But that hurt, and it made me mad. People were making fun of me.” As he told the L.A. Times’ Scott Miller in 1993: “A lot of ballplayers didn’t hit .215, which is what I hit. A lot of guys who played didn’t hit that. I got sick and tired of hearing about the Mendoza Line. Kids write to me about it. . . . Whenever a guy is hitting below .200, my name comes up.”

We also have:

Vince Evans, Los Angeles Raiders quarterback (1987 to 1995)

Doug DeCinces, California Angels third baseman (1982 to 1987)

Tyus Edney, UCLA basketball guard (1991-92 to 1994-95)

Jimmy Rollins, Los Angeles Dodgers shortstop (2015)

A.J. Pollock, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (2019 to 2021)

Saku Koivu, Anaheim Ducks center (2009-10 to 2013-14)

Gareth Bale, LAFC midfielder (2022)

Jose Cifuentes, LAFC midfielder (2020 to 2023)

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 11: John Elway”