This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 67:

= Les Richter: Los Angeles Rams

= John Papadakis: USC football

= Duval Love: UCLA football, Los Angeles Rams

= Luis Sharpe: UCLA football

The most interesting story for No. 67:

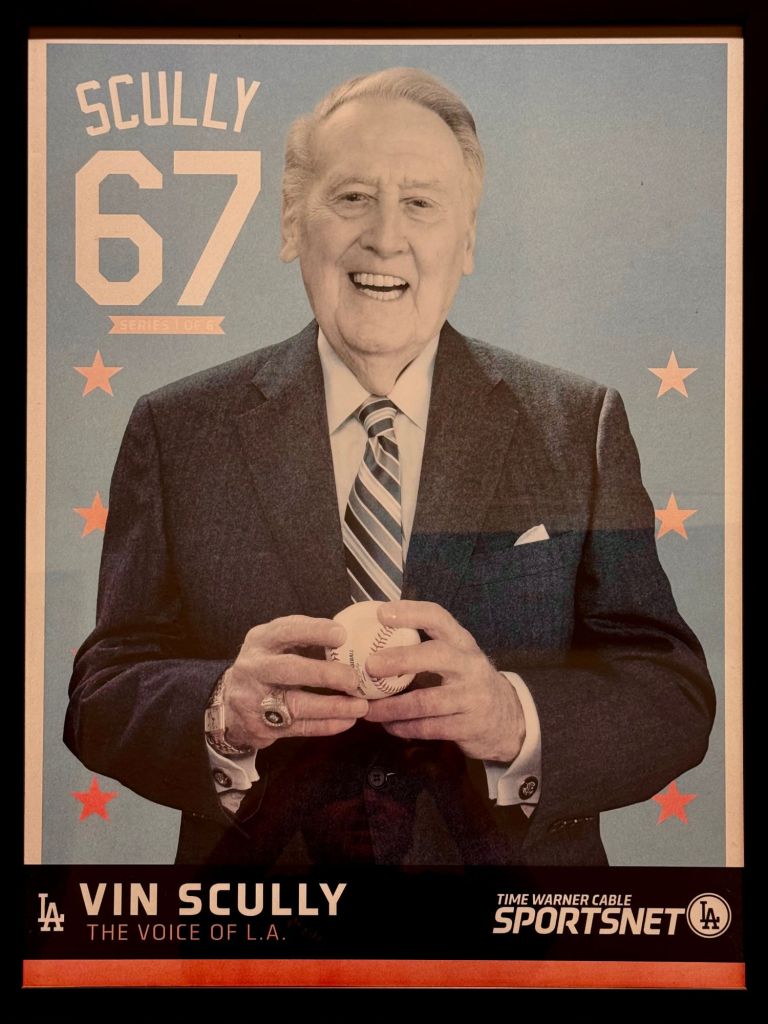

Vin Scully, Los Angeles Dodgers broadcaster (1950 to 2016)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Los Angeles Coliseum; Dodger Stadium; Pacific Palisades; Hidden Hills

All automobiles in the United States are required to have a Vehicle Identification Number. Car manufacturers started using them in 1966. By 1981, it was a standardized 17-character alphanumeric code.

In Southern California, the only VIN number that matters is 67.

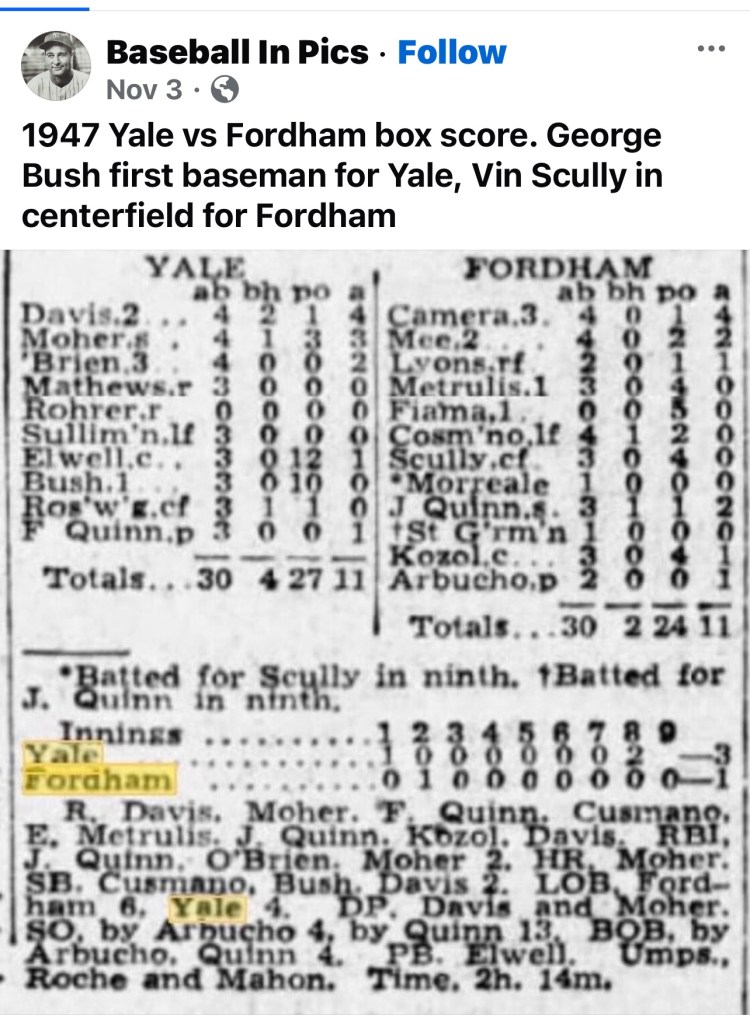

Vin Scully retired from broadcasting Los Angeles Dodgers’ games after the 2016 season. That meant he had put in 67 seasons, going back to 1950 when, as a 22-year-old, he started doing games in the middle innings with Brooklyn’s Dodgers. He was fresh out of Fordham University, a redhead somewhat green learning the craft from Red Barber.

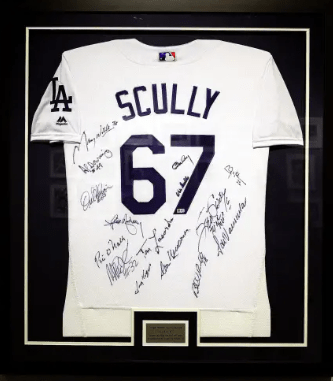

There is no official Vin Scully No. 67 Los Angeles Dodgers jersey. When the Dodgers gave away Scully tribute jerseys in 2023, it had no number – just a red microphone logo on the front where a number should be, and a blue mic on the back. There was a Union 76 patch on the arm — the reverse of 67, perhaps by luck. Mostly, it was because Scully had voiced the oil company’s commercials for so many decades, it seemed simpatico.

(There’s also a reason to believe that had Vin Scully not been locked in as the Dodgers’ voice, Union 76 would not have continued being a sponsor, and the completion of Dodger Stadium may have been more problematic in the early 1960s).

Online, there are dozens of variations of “Scully 67” jerseys offered. At the LADFanstore alone, there are more than a dozen choices, including “black holographic.”

Don’t do it.

An otherwise random prime number now attached in perpetuity to someone who, it has been said, made the greatest impact of any sports figure in Southern California sports history.

Uniformly, No. 67 belongs to Scully, and it fits into the parameters of our “jersey” list here, because so many have created a Dodgers uniform in his honor in so many variations.

That’s the story we’re selling. And so many keep buying.

When Los Angeles Kings’ Hockey Hall of Fame broadcaster Bob Miller visited Scully during his final season and presented him with a No. 67 Kings jersey, Miller remarked: “Vin, when you started announcing, a high number like 67 probably meant you were a prospect, you hadn’t yet made the team.”

Scully laughed and replied: “I’m trying my best.”

Our way to honor No. 67 waspulling together “Perfect Eloquence: An Appreciation of Vin Scully” (University of Nebraska Press, 288 pages), released in May, 2024.

When we started the project of recruiting people to write essays about how Scully impacted their lives and surmising his legacy, there were 67 who signed up. We took that as a sign.

Here is the introduction to “Perfect Eloquence”:

An elegant New York Times summary of all the global luminaries who died in 2022 asked if any of them had a common thread. Queen Elizabeth and Pope Benedict XVI? Pelé and Sidney Poitier? Bill Russell and Barbara Walters?

In his piece headlined “Unlikely Parallels in a Year of Momentous Deaths,” writer William McDonald also patched in this paragraph:

“Four figures in Los Angeles Dodgers history departed within a few months: Roz Wyman, who as a member of the Los Angeles City Council was central to luring the team from Brooklyn to the West Coast in the late 1950s; Maury Wills, who stole bases with blazing regularity for the team in the ’60s; Tommy Davis, a batting star who led Los Angeles to two World Series titles before injuries derailed a potential Hall of Fame career; and Vin Scully, who sat in the broadcast booth marveling at their exploits as one of the game’s most venerated announcers.”

Scully might have considered this an appropriate way to be sentenced into the great beyond—well punctuated, no dangling participles. His mention came after the others, no more “fuss and feathers,” as he would say.

He might even be agreeable with the label announcer. Many use it interchangeably with broadcaster. By definition, an announcer is one who announces; a broadcaster presents and discusses information. Scully was far more the latter.

Going a step further, Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray once wrote about Scully, “He didn’t broadcast a game. He narrated it.”

At the end of the 2015 season, Scully announced (that’s the proper use) the next summer would very likely be his last calling games for the Dodgers. It came as a blessing. He wasn’t going to pull an Irish goodbye and just disappear on us. He gave a clear runway. We all had time to prepare countless bouquets of thank-yous.

Five more years went by. Scully showed what retirement past the age of ninety could look like: just being there for his ailing wife, Sandi, and his children, grandchildren, and great-grandkids; popping into the ballpark for ceremonial moments of playoff pomp and circumstance; accepting even more lifetime achievement awards; reciting poetry before a live audience at the Hollywood Bowl; making public appearances to boost charity fundraising.

When Scully died, obituary writers leaned most into his professional life and times. Very few knew about his very personal and often private endeavors. That was the tricky part. Scully wasn’t an open book. He politely declined any attempts to cooperate, or authorize, a self-indulgent biographical project. So, writing about him became a bit of a Citizen Kane–type excavation project for those who had connections and resources to capture, perhaps, his true Rosebud.

McDonald’s Times essay wrapped up with a somewhat esoteric point: There was “no particular lesson to be drawn from these clusters of contemporaneous deaths.” He declared that, like any death, those in 2022 were “experienced alone and mourned individually. . . . It’s for those of us who record such deaths, and read about them, to notice the remarkable parallels. And there we have to leave it, perhaps a little mystified. Death, in its inscrutability, doesn’t explain itself. . . . All made a difference, but all died knowing that their work was unfinished, that as the world spun on without them, others would have to pick up their banners and carry them into the next year, and the next.”

So much communal grief had already been laid heavily on the planet by the covid-19 pandemic to that point. Yet Scully’s passing of natural causes may have hit too many of us like a supernatural experience. On August 2, 2022—the deuces were wild—Southern Californians who tuned into the midweek night game between the Dodgers and Giants from San Francisco heard Dodgers broadcaster Joe Davis take a deep breath and deliver the news during the game.

When information like that brings people to their knees, there is a reason. We prayed. For decades, Scully’s presence at Dodgers games had been a communal experience for baseball fans and beyond. This moment wasn’t any different.

If our world was about to spin ahead, there had to be a way to pick up the banner for him and unfurl it forward—as he did with his own banner from the Dodger Stadium broadcast booth on his final home game, thanking all for their impact on his life.

Broadcasting may have been Vin Scully’s universally appreciated vocation. He was considered the best of the best at it, in ways we all could validate from under the blanket as he tucked us into bed each night with his stories.

Ultimately, that is not what defined him. Vin Scully’s actions spoke louder than his Hall of Fame words.

If given a chance to offer a personal eulogy, a tribute of thanks, what might anyone want to share? What about him do we carry with us today? That’s the goal here.

A public celebration of his life was limited to a brief pregame ceremony before a Dodgers home game days after his passing. His funeral Mass shortly thereafter was private.

I am not seeking some sort of poetic closure. It is more about creating a platform for those, like me, who want something to preserve: character and ideas and a template for living, especially if we can figure out a way to play it forward.

In the weeks leading up to his retirement in September of 2016, one reporter asked Vin how he would want to be remembered.

“I really and truly would rather be remembered — ‘Oh yeah, he was a good guy.’ Or, ‘He was a good husband, a good father, a good grandfather.’ The sportscasting? That’s fine if they want to mention it. But that’ll disappear slowly as — what is it, the sands of time blow over the goose?

“The biggest thing is I just want to be remembered as a good man, an honest man, and one who lived up to his own beliefs.”

I believe that to be the case. Many want to make more precise analogies, and that’s natural.

“He ranks with Walter Cronkite among America’s most-trusted media personalities, with Frank Sinatra and James Earl Jones among its most-iconic voices, and with Mark Twain, Garrison Keillor, and Ken Burns among its preeminent storytellers,” Sports Illustrated’s Tom Verducci wrote in a 2016 profile on Scully. Five years later, under the headline “The Beautiful Life of Vin Scully,” Verducci added that he was “a modern Socrates, only more revered, simultaneously a giant and our best friend.”

These points are well taken. In today’s Google-fied world, a few quick keystrokes can find a plethora of archived work. Take these interesting examples I happened to stumble on: a strikeout that ended Don Larsen’s 1956 World Series perfect game, Orel Hershiser’s last out to clinch the Dodgers’ title in the 1988 World Series, and Clayton Kershaw’s 2014 no-hitter. Scully was on the call for all three, spanning nearly sixty years. Yet he exclaimed the same thing after each ending strikeout: “Got him.” And then the crowd took over.

But as much as Cronkite was a trusted source in his day, Scully might also be easily overlooked as time marches on. Too many other new people, places, and things somehow are referred to as “the best.” We need testimonials of what we know happened in our lifetimes, as reference points for the future.

I understand the profound personal connection so many had with Scully. It feels a lot like falling in love — that is something of the moment. By nature of the broadcast medium, Vin’s descriptions and stories were often things of the moment. And moments can evaporate.

As Bob Nightengale, the USA Today baseball writer, explained in his 2022 tribute piece, “If you knew Vin, if you ever met Vin, if you just listened to Vin, you loved Vin.”

On what would have been Vin Scully’s ninety-fifth birthday, I started reaching out to colleagues and sifted through storage boxes of notes and clippings, trying to connect dots and dashes. Common themes emerged. Bob Costas could explain not just how Scully found himself in another important moment but also the way he could elevate it even more. Al Michaels felt a personal connection as a native Brooklyn Dodgers fan moving to Los Angeles. Baseball Hall of Fame president Josh Rawitch and Gil Hodges Jr. could explain Scully’s patriotic call to duty. Former Dodgers owner Peter O’Malley considered Scully like a brother. What other baseball owner can say that about a star employee?

Add to that another layer, deeper than just what you heard or saw. Vin’s devotion to his faith and family, his sincerity, and his efforts to inspire dozens to attempt his career path weren’t often revealed to the general public. He was never caught up in the trappings of celebrity and fame but could laugh along with it. As Steve Garvey says, Vin handled it all with grace.

In 2016 the Dodgers petitioned the City of Los Angeles to change the name of the main road coming to the stadium from Elysian Park Avenue to Vin Scully Avenue. It was a missed opportunity. Back at the team’s Vero Beach, Florida, home, they once had a small road named for him called Vin Scully Way.

Vin Scully’s way was to provide an example of what humility, dignity, and humanity look like, which is especially poignant these days as we search our past for principled answers amid a turbulent point in existence. When a lack of integrity, common decency, and respectful communication skills threaten to chip away at society, Vin was a reminder, a compass of the true foundation of patriotism, hard work, and family values.

In his story in Sports Illustrated, Verducci explained that, when Scully attended Fordham University, all freshmen took a seminar class called Eloquentia Perfecta. Translated from Latin, it means “perfect eloquence.”

“It emerged from the rhetorical studies of the ancient Greeks, codified in Jesuit tradition in 1599,” Verducci elaborated. “It refers to the ideal orator: a good person speaking well for the common good. It is based on humility: The speaker begins with the needs of the audience, not a personal agenda. Vin Scully was that ideal orator. A modern Socrates, only more revered. He was an amazing firsthand witness and chronicler of history. . . . And yet never did Vin place himself above the people and events he was there to chronicle.”

Scully’s friend Jackie Robinson once said it: “A life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives.”

That impact is what I am trying to quantify. He was perfectly eloquent in many ways.

I created nine chapters—innings, as it turned out—that capture prominent themes of Vin’s life, professional and personal. They often fed into each other. I start each theme with my interpretation based on my experience, then other writers follow with their perspective. This started with just a small number of contributors—journalists and broadcasters, mostly—whose creative prose could take things to new levels. It was by some divine intervention perhaps that as the project gained momentum, I landed on exactly sixty-seven essays at the deadline to submit the manuscript. That is one for each year Vin broadcast games for the Dodgers.

Here is my attempt to show Vin Scully’s impact on others, based on the way he lived, which reverberates to this day.

(And here is the plaque installed at the L.A. Coliseum’s Memorial of Honor for Scully, calling him “the enduring voice of summer in Los Angeles):

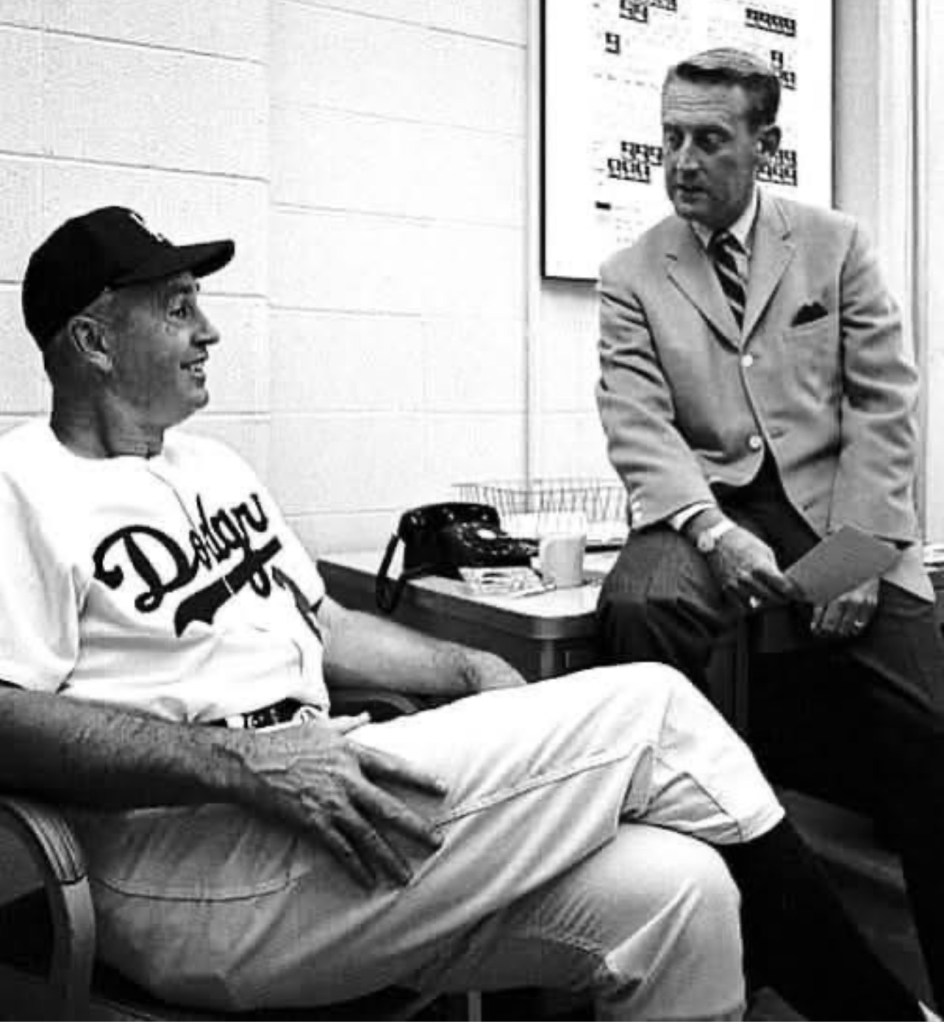

For the record — and specifically, for those scoring at home — Scully did wear a baseball uniforms while playing center field for the Fordham Prep high school team and at Fordham University during the 1940s.

Photos prove it.

Some of his friends in the Dodgers broadcast booth eventually did some research and worked out a deal with Fordham University to verify that he wore No. 17 in college.

They then made a replica jersey for him and framed it up.

Scully admits he also wore a Dodgers uniform once. In an actual game.

The story is included by sportswriter Steve Dilbeck in “Perfect Eloquence.” This is Scully talking:

“One year we’re in Chicago to play the Cubs, and for some reason, we’re not broadcasting the game. And Tommy (Lasorda) asks me if I’ve ever sat in the dugout for a game. I tell him ‘no’ and he says, ‘You have to try it.’ I said as long as it’s cleared by the umpires beforehand. I don’t want them throwing me out. So I put on a uniform — spring training tryout No. 76, but not for Union — and waited until almost before the game starts and walk through the Wrigley hallway, sit in the dugout and pull my cap down all the way to my eyes. I don’t want anyone to even notice me. “After the Dodgers are retired in the top of the first, (first base coach) John Vukovich yells over at me, ‘Hey, Scully!’ And he throws me a baseball. I catch the ball and written on it is, ‘If a fight breaks out, I want you.’ And it was signed (by Cubs manager and former Dodgers player) Don Zimmer. All the Cubs are in their dugout, laying down laughing.”

The legacy

When ESPN’s Mike Greenberg did his 2023 book (with producer Paul “Hembo” Hembekides) called, “Got Your Number: The Greatest Sports Legends and the Numbers They Own,” the chapter on No. 67 belonged to Scully.

Greenberg’s book was more about taking a number related to sports – jerseys, dates, accomplishments – and expanding on them. Scully fits his template, as Greenberg explains in part:

“When Scully signed off for the final time by saying, ‘I have said enough for a lifetime,’ he had literally done just that. … Somehow even mentioning that Scully was named top sportscaster of all time by the American Sportscasters Association in 2009 feels insufficient to fully explain his impact. Vin Scully was so much more than a great broadcaster. He was a friend, even if you never met him, a trusted and beloved voice on a hot summer afternoon or a crisp, autumn night, for as long as practically any sports fan alive can remember. In the entire sporting history of our nation, there aren’t but a handful who have left anywhere the mark he did on our ears, our minds or our hearts.”

Greenberg added a blurb to our book included in its promotion:

“It is very likely that Vin Scully’s voice reached the ears of more sports fans than any in the history of our country. Anyone who loved listening to him, which means pretty much everyone, will enjoy this look at the man behind those memories, and the extraordinary life he led.”

Here is the official website we generated for the book.

Any other SoCal broadcasters honored with a number?

Dick Enberg: Here is a ceremony in 2017 when Enberg was given his own No. 8 UCLA jersey at Pauley Pavilion to recognize that, from 1966-75, he called eight of the school’s national championship seasons under coach John Wooden. “That’s not going to happen again,” Enberg said before the game. “Who was looking over me? To be able to come in and ride the Wooden Wave.” Enberg, then 82, had retired in late ’16 after a 60-year career that started with Southern California sports play-by-play — including the Angels and Rams — and then went to national network coverage of the Final Four, Olympics, Super Bowl, Wimbledon, Masters and U.S. Open while uttering countless calls of “Oh my!” Enberg said his career highlight was calling the Bruins’ game against Houston at the Astrodome in 1968. It was the first non-playoff college or NBA game shown in prime time. He described the game as being “the rocket ship” that popularized college basketball. The media room at Pauley Pavilion was also named in his honor.

By the numbers, Enberg also put in 10 seasons calling the California Angels for KMPC-AM (710) and KTLA-Channel 5, working six seasons with Don Drysdale as his partner. Enberg also replace the first voice of the L.A. Rams, Bob Kelley, upon his death in 1966 and stayed with the NFL team through 1977 on KMPC-AM (710), working with Dave Niehaus and Drysdale.

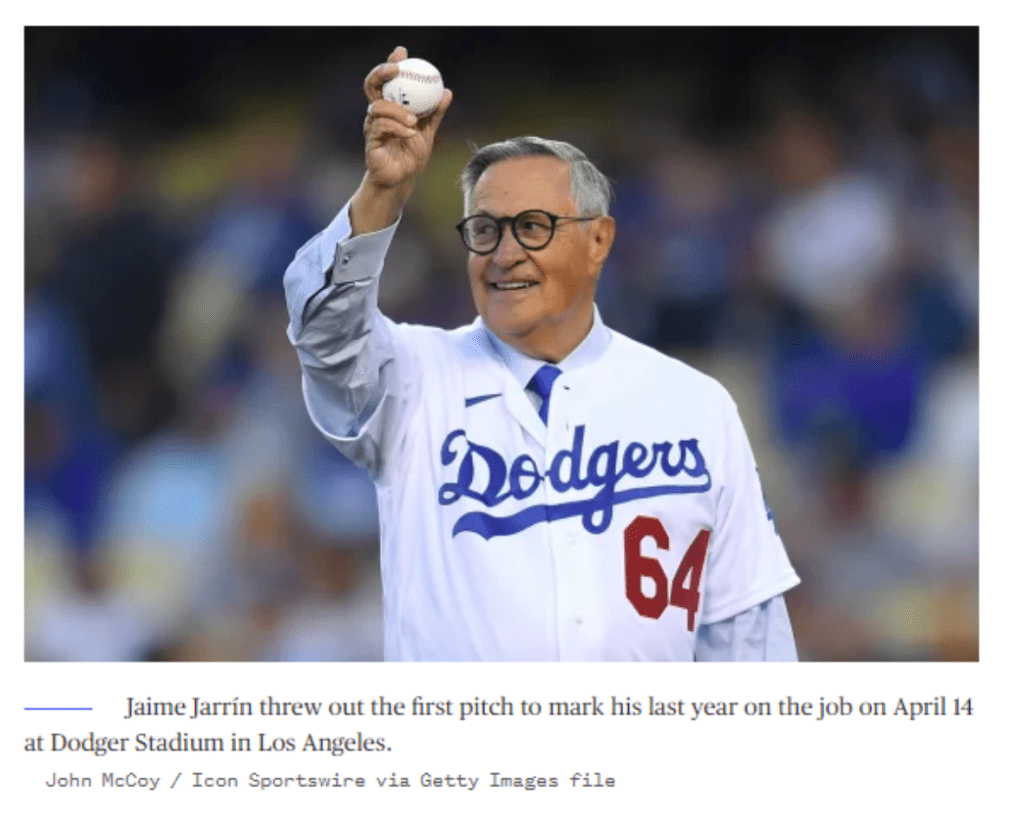

Jaime Jarrin: Sixty four years is what Jarrin spent as the Dodgers’ Spanish-language broadcaster, which included a stop in the Baseball Hall of Fame’s wing dedicated to the profession in 1998 — joining Scully and Enberg. Like those two, he also has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, also in ’98. As Jesse Sanchez of MLB.com wrote about Jarrin in 2020: “He is known as ‘el padrino,’ the Spanish word for the godfather. To others he is ‘el maestro,’ which means the teacher. ‘I am just pleased to be able to serve my community, because when I do a game, I am not relating what’s going on the field, I’m also giving the audience some type of entertainment,’ Jarrín said. ‘There are so many people who work so hard, especially in our communities, and to be able to give them baseball in their own language is an honor for me’.” Jarrin studied journalism and broadcasting at Central University of Ecuador, came to the United States at age 16, became the news and sports director at Los Angeles’ Spanish radio station KWKW when the Dodgers moved to L.A. in ‘58 and became the play-by-play voice for the team when KWKW bought the Spanish-language rights to Dodgers’ games the next year, when they won the World Series. Before he retired in 2022, Jarrín called three perfect games, 21 no-hitters, 29 World Series, 26 All-Star Games and countless postseason series. He was inducted into the Dodgers’ Ring of Honor in 2018.

Chick Hearn: No jersey numbers but his name and a microphone are among the retired numbers on the wall at Cryto.com Arena. If a jersey was made for him, it could be 41 (the number of seasons he called the Lakers on radio and TV), 3,338 (the consecutive games he called between November 21, 1965 and December 16, 2001) before he died at age 85 in 2002.

Who else wore No. 67 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

Les Richter, Los Angeles Rams center, linebacker and kicker (1954 and 1955):

The Pro Football Hall of Famer (Class of 2011) based on his nine years in L.A. entered the league wearing No. 67 for his first two years, the same number he wore at Cal. He switched to No. 48 as he played more middle guard and middle linebacker after the 1955 season. How he even landed with the Rams is a historic story unto itself. The All-American guard and linebacker was the second player selected overall in the 1952 NFL Draft by the New York Yanks (after the Rams picked Vanderbilt quarterback Billy Wade at No. 1). But Richter spent just two days with that franchise — it folded and was sold back to the NFL, and assets of the club, including the signing rights to Richter, were granted to the expansion Dallas Texans. Richter said he wouldn’t sign with Dallas.

On June 12, 1952, the Rams shipped 11 players to Dallas for the rights to Richter — the biggest trade in league history to that point. As it turned out, the Rams came out very much on the right end of the deal. They gave up 1) fifth-year fullback Dick Hoerner (wearing No. 31, their all-time leading rusher at the time), but he only played one more season (’52, in Dallas, and retired), 2) fourth-year defensive end/linebacker Tommy Keane (wearing No. 10, who would play four more seasons and collect 32 more interceptions and was named to the 1953 Pro Bowl with Baltimore, the team that ended up with most of the Dallas players after that 1952 season); 3) halfback Billy Baggett (the Rams’ 22nd round pick in 1951, just did kickoff and punt returns in his one year in Dallas in ’52) ; 4) tackle Jack Halliday (only played the ’51 season with the Rams and never played again); 5) fullback Dick McKissack (never played in L.A., only played one more game with Dallas); 6) center Joe Reid (retired after his one year in Dallas), and 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11) running back Dave Anderson, center Aubrey Phillips, defensive back George Sims, linebacker Vic Vasicek and defensive end Richard Wilkins, all of whom never played again.

Even then, Richter wasn’t coming to L.A. right away — he spent two years in the U.S. Army during the Korean War before playing as a rookie in 1954. In the 1955 season, he led the league with 24 field goal attempts (making 13), and earned his second Pro Bowl invitation. We have him covered as well in the entry for No. 48.

John Papadakis, USC football linebacker (1970 to 1971):

“I never wanted that number,” John Papadakis says about how he came to wear No. 67 when he came to USC. Instead, he wanted to be a fullback. And wear a fullback number. “My heart was set to play for USC, the 1967 National champions, and I was thrilled when they asked me to join their team.” The Rolling Hills High graduate who played for USC in the 1970 Rose Bowl (a 10-3 win over Michigan) would become more famous as a restaurateur — Papakakis’ Taverna in San Pedro from 1973 to 2010, an author (“Turning of the Tide: How One Game Changed the South”), a civic visionary, a troubadour and a member of the Los Angeles Sportswalk of Fame.

Ryan Kalil, USC football center (2003 to 2006):

Winner of the Pac-12’s Morris Trophy as a senior, signifying the top offensive lineman in the conference, Kalil, out of Anaheim’s Servite High, was on two Trojan national title teams and part of the cover of the Sports Illustrated 2006 College Football Preview issue. He won the USC Bob Chandler Award in 2005. At 6-foot-2 and 300 pounds, Kalil was a second round pick by Carolina in the 2007 NFL draft and played 12 pro seasons before getting into the TV and film business.

We also have:

Duval Love, UCLA football defensive lineman (1982 to 1984) and Los Angeles Rams (1985 to 1991)

Luis Sharpe, UCLA football defensive tackle (1978 to 1981)

Anyone else worth nominating?

3 thoughts on “No. 67: Vin Scully”