This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 15:

= Davey Lopes: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Shawn Green: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Ann Meyers: UCLA women’s basketball

= Tim Salmon: California/Anaheim/Los Angeles Angels

= John Sciarra: UCLA football

= Jack Kemp: Los Angeles Chargers

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 15:

= Vince Ferragamo: Los Angeles Rams

= Ryan Getzlaf: Anaheim Ducks

= Laiatu Latu: UCLA football

= Darryl Evans: Los Angeles Kings

= Rich Allen: Los Angeles Dodgers

The most interesting story for No. 15:

Ann Meyers Drysdale: UCLA women’s basketball (1974 to 1978)

Southern California map pinpoints:

La Habra (Sonora High); Westwood (UCLA); Dodger Stadium

In a male-dominated, and often testosterone infested, sports coal mine, Ann Meyers accepted the ongoing challenge of being the female canary sent in to see if things were safe.

Time and time again, just give her a crack, and she’d find another way to kick it the door open.

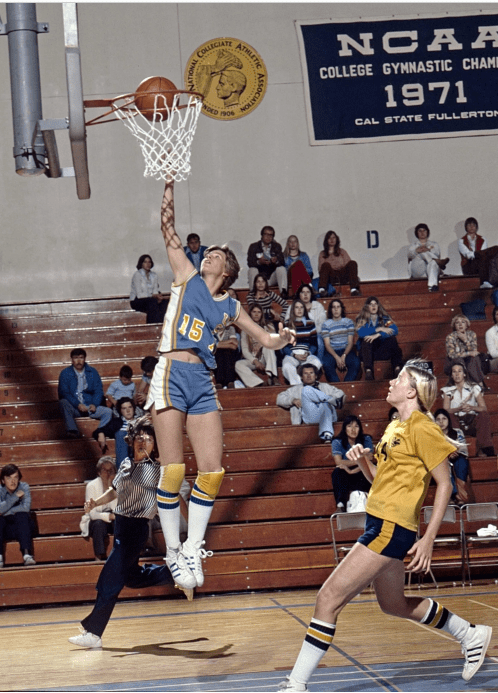

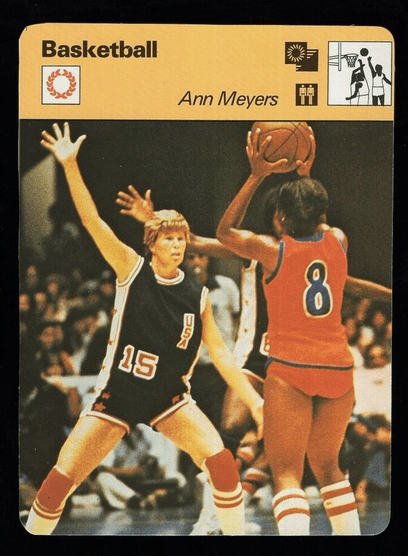

She must have felt 15 feet tall when the Indiana Pacers had her hold up one of its jerseys with her name across the No. 15 in September of 1979. The number was special to her. It’s what she wore the four previous seasons as barrier-breaking All-American guard at UCLA, coming off a 27-2 season with a team that won the AIWA title under Billie Moore.

After college graduation, the pride of Sonora High of La Habra had already declined signing with the Women’s Professional Basketball League, wanting to keep her amateur status for the 1980 Olympics. But world events were changing fast.

The U.S. was talking about a boycott of those Summer Games in Moscow — the largest protest in the history of the Olympic movement. But it hadn’t officially happened yet.

Pacers owner Sam Nassi asked her about the tryout as NBA teams were in training camp. Her decision was to sign a one-year, $50,000 “no-cut” deal with the team — a personal services contract negotiated by her brother, Marc — that included a three-day tryout. It was a leap of faith that something might happen positive at a time when she might face disappointed at missing the Olympic Games, which she participated in back in 1976 and wanted to keep that momentum moving forward.

After all, Title IX was just working its way into the sports vocabulary, and Meyers’ name was an important part of the sentence structure as a real, live game-changing example of what it could achieve.

Still, at 5-foot-9 and 140 pounds, it was reasoned in a Sports Illustrated write up that she “is simply too small to perform in a league in which the player average is 6-foot-6 and 205 pounds.”

(This was about six years before the Atlanta Hawks drafted 5-foot-6 guard Spud Web out of North Carolina State, who won the NBA Slam Dunk Contest).

“If I didn’t think I could compete, I wouldn’t be here,” she said, noting her older brother David was already a member of the Milwaukee Bucks, out of UCLA. “I don’t want to embarrass anyone, including myself.”

Coach Slick Leonard, who said he had never seen Meyers play, admitted that it was “unusual” to sign a free agent to a guaranteed contract before training camp opened.

Red Auerbach, the Boston Celtics executive, chimed in: “I know Annie and she’s a nice girl, but this is reminiscent of Bill Veeck signing that midget.”

That comment could have made her feel 15 inches tall.

Lusia Harris, a 6-foot-3 center who led Delta State to three straight AIAW national titles, was a seventh-round choice in the 1977 NBA draft by the nearby New Orleans Jazz, which still made her the first and only woman officially drafted by an NBA team. She wasn’t able to try out because she was pregnant. She’s in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. In 1969, the San Francisco Warriors tried to draft 5-foot-11 forward Denise Long after she finished high school in Iowa, but the NBA blocked it because she didn’t meet the criteria to be drafted — in part because of her gender.

As Meyers stepped onto the court at Indiana’s Hinkle Fieldhouse during the first day of tryouts, she believed she had a real shot at becoming the first woman to make it into the NBA.

“I grew up playing against boys my whole life, so this was nothing new for me,” Meyers said.

As the camp played out, a half dozen players were cut, but Meyers remained. Eventually, Leonard called her into his office.

“I cut her just like any other player,” Leonard said at the time. “I felt bad when we started the cut down. I felt bad about it. She really did do a great job. I was proud of her.”

This was another first for Meyers: First women cut by an NBA team. But she already knew this was a pivotal moment, for her to work for the Pacers, learning the broadcasting side, working in public relations.

But that didn’t happen either. Once she left, she didn’t get the rest of the $50,000.

It would not stop her from being persistent.

The story

Fifteen reasons why Ann Meyers Drysdale becomes the most noteworthy No. 15 in SoCal sports history:

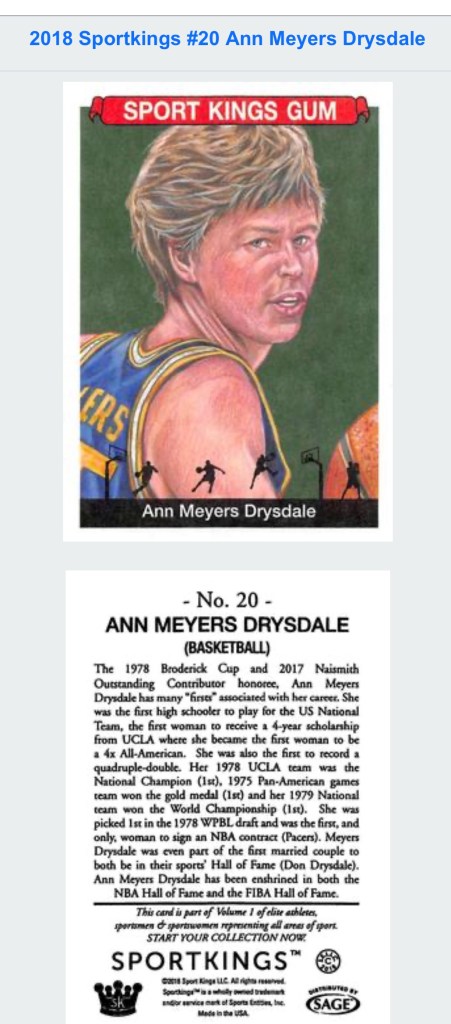

= In 1974, she was the first high school player ever to make the U.S. Women’s National Team. She was a senior at Sonora High in La Habra.

= In 1974, she was the first female recipient of a full athletic scholarship at UCLA. Her brother, David, was an All-American senior for the men’s team that that point. The school got its money’s worth. She earned two varsity letters in volleyball and one in track and field, as well as trying out for the tennis team.

= In 1976, she was a member of the first U.S. women’s basketball team to compete in the Summer Olympics. The team won the silver medal.

“When I was in the fourth grade, it was my dream to be an Olympic athlete,” Meyers once said. “At that time, I was very involved in track and field. I was a pentathlete and a high jumper. I had read a book on Babe Didrikson, so that was my dream to represent my country. As I got older, I was very into basketball. I had an older sister and brother who played. I had a dad who played. Basketball opened up a lot of doors for me. Title IX was happening. But it wasn’t until the early ‘70ss that we even knew that there would be a US women’s basketball team in the Olympics.”

= In 1978, against Stephen F. Austin on Feb. 18, she was the first woman to record a quadruple double in UCLA history — 20 points, 14 rebounds, 10 assists and 10 steals.

= In 1978, she won the Honda Award as the outstanding women’s college basketball player of the year, and the Broderick Cup as the outstanding women’s athlete. Her career totals at UCLA: 97 games, 1,685 points (17.4 per game average), 8.4 rebounds, 5.6 assists, 4.2 steals and 1.0 blocked shots a game.

= In 1978, she was named the first four-time All-American women’s basketball player.

= In 1979, after already been the first player taken in the Women’s Professional Basketball League draft of 1978, she agreed in November to play for the New Jersey Gems, months after the tryout with the NBA’s Indiana Pacers didn’t happen. She became the WPBL’s first MVP (sharing it) with by season’s end in 1980.

= In 1979, she was part of the first Women Superstars competition for ABC. She finished fourth. She won the next three competitions in 1980, ’81 and ’82.

= In 1985, she was inducted into the International Women’s Sports Hall of Fame.

= In 1988, she was the first woman inductee into the UCLA Athletics Hall of Fame.

= In 1993, she was the first woman’s player inducted into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield, Mass. She was also part of the Basketball Hall’s induction of the 1976 U.S. Olympic team in 2023.

= In 1999, she was included in the first group inducted into the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame in Knoxville, Tenn., which was the first Hall of Fame dedicated to any women’s sport.

= In 2007, she was added to the FIBA Hall of Fame as part of its first class.

= In 2018, the Basketball Hall of Fame started giving out the Ann Meyers Drysdale Award to the top shooting guard in women’s basketball.

= In 2019, she was the first woman inducted into the Southern California Sports Broadcasters Hall of Fame.

OK, one more to make it a Sweet 16: In October of 2025, in honor of the 50th anniversary of the women’s basketball poll, The Associated Press assembled a list of the greatest players since the first poll in 1976. Meyers Drysdale was included on the all-time second team. She was also thought enough to be included on the panel doing the voting.

The context

In her autobiography, “You Let Some GIRL Beat You? The Story of Ann Meyers Drysdale,” she explains in Chapter 3:

“Players may tell you that numbers don’t matter, but it did to me.”

It was important to her at UCLA that she had No. 15 — it was the number her father, Bob, wore when he played at Marquette from 1944 to ’47.

“I was also a big Hal Greer fan, and he was one of the few NBA guy who wore No. 15 back then,” she once told us.

The journey to 15 had some detours. But the numbers were connections.

“I had No. 17 in junior high because I was a huge John Havlicek fan growing up,” she explained. “In high school, for my senior year, I wore my brother David’s No. 34, when he was at UCLA.

“On the 1976 Olympic team, I was able to wear No. 6, which I took in honor of Bill Russell and, then, Julius Erving, and both are very good friends of mine now, as is Hondo.”

Then there was the No. 14 she ended up wearing with the New Jersey Gems of Women’s Basketball League in 1979. She hated it.

Again, as she explains in her book:

“When I finally got to New Jersey, the first order of business was to get my uniform,” she wrote. “I was polite when requesting my jersey number … No. 15 was my number at UCLA. I really liked No. 15.

“They told me they didn’t have it. I was dumbfounded. Can’t you make it?

“OK, then I’ll take No. 6. ‘Somebody else has it,’ was the reply.

“The whole thing was starting to feel bizarre. I ended up with No. 14 and consoled myself with the knowledge that Oscar Robertson and Gil Hodges wore it as well.”

That one year in the Gems felt tarnished. She got into broadcasting instead.

In 1990, her UCLA No. 15 jersey was retired in a ceremony at Pauley Pavilion that included the school retiring No. 33 for Kareem Abdul-Jabbar/Lew Alcindor, No. 32 for Bill Walton and No. 12 for Denise Curry, as all four were (at least) three-time All American basketball players for the school.

In 1995, her jersey at Sonora High was retired and displayed. That year, she was inducted into the National High School Hall of Fame.

And as for that No. 15 Indiana Pacers jersey she wore during the tryout? It went up for auction along with several other things in her collection in 2016 and fetched more than $21,000.

The legacy

Ann Meyers Drysdale wasn’t an accidental broadcaster when she pivoted from a ground-breaking Basketball Hall of Fame playing career in the 1970s and ’80s, looking for a meaningful way to stay involved in the sport.

Her dedication to basketball for decades brought more Hall of Fame recognition.

The Southern California Sports Broadcasters organization, which inducted three dozen men in its Hall of Fame since founder Tom Harmon was first recognized in 1992, made Meyers the first women inductee in 2019.

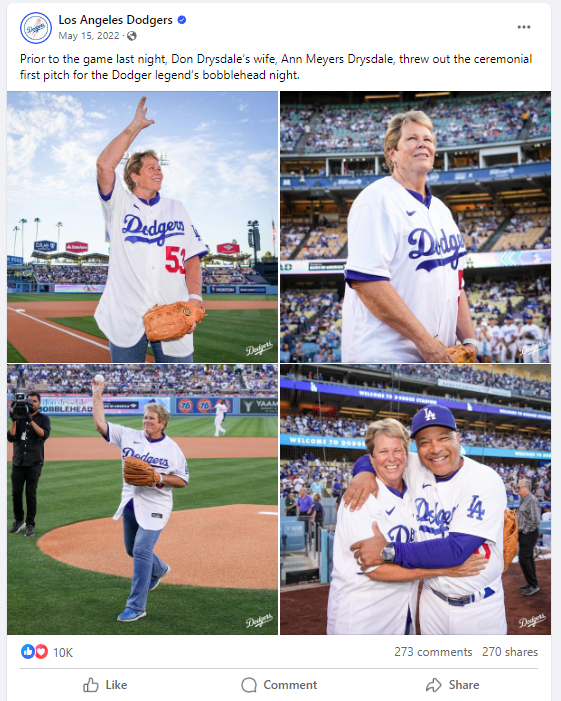

The list of previous Hall inductees was her late husband, Don Drysdale — and she accepted the honor on his behalf in 1998, five years after his death, reflecting he work not just on calling games for the Dodgers but also the Angels and Rams.

“Honestly, I never imagined something like this, and it’s important to me to be grateful for so many who have opened doors for me, many without me even knowing about it,” Meyers Drysdale told us at the time.

“It’s totally humbling, especially when I see those who are in this group. There is a real sense of pride for me. Even as a young player with the Dodgers, Don knew he wanted to be a broadcaster and he worked at his craft.”

Her broadcast career started in a classroom at UCLA. As a fifth-year senior, and while playing for the U.S. national team, she took a well-known class in the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television taught by Art Friedman. Former UCLA basketball standouts Keith Erickson and Lynn Shackelford, who would go on to become Lakers broadcasters, had taken the class and came back as guest speakers. Eventually she hustled to get into the famed Don Martin School of Radio & Television Arts & Sciences in Hollywood, an organization in its early years that was advertised as “for men only.”

“This was a time when I only recall seeing someone like Phyllis George and Jayne Kennedy as women working in the business,” said Meyers Drysdale, who, in 1999, received a lifetime media award by the Women’s Basketball Coaches Association.

She did nine seasons on the local broadcasts of the WNBA Sparks — the first season next to Chick Hearn.

And if there’s every a chance to put on her Drysdale No. 53 jersey and represent the family at Dodger Stadium, she’ll be there.

For all that, the SCSB award feels like “a sense of family and togetherness in the history of L.A. broadcasting, and it’s important for more women to continue down this road,” Meyers Drysdale said. “I like to think my ability to work hard and call games has mattered. Even if I was overlooked, it just made me want to work harder.”

The sixth of 11 children in her family, with a daughter Drew who competed in sports at UCLA to go with her two sons, keeping the family tradition of sports alive, the legacy continues.

In his book, “Got Your Answers: The 100 Greatest Sports Arguments Settled,” ESPN’s Mike Greenberg puts Meyers-Drysdale at the top of his list of the “Top 10 athletes of the ’70s who deserve to be better remembered.” Ahead of Lee Trevino, Chuck Foreman, Dave Cowens, Steve Garvey, Guillermo Vilas, Olga Korbut, Harold Carmichael, Craig Nettles and George McGinnis. Greenberg’s point is, after presenting her resume, “if reading all of this causes your jaw to drop, my point is made.”

The postscript

Somehow, we failed to mention that Meyers is also in the Polish Sports Hall of Fame. For real. In 2016.

There was also a time in 2017 when we reached out to her for clarification. Deb Antonelli had just been added to CBS’ roster as an NCAA men’s tournament game analyst, called “the first female game analyst in more than two decades.”

“It’ll be nice when anything related to gender in this case is not a story,” Meyers Drysdale, the last women assigned first- and second-round games for CBS during the men’s event from 1992-1995, admitted to us. “And even then, I wasn’t the first to do it.”

That would be Mimi Griffin, hired by the NCAA to cover early-round men’s games when ESPN had the coverage in 1990, then getting one more year with CBS as it took over in 1991.

Meyers Drysdale then heaved a bit of a sigh.

“I’ve always said that basketball is basketball. At this stage, the fact we’re even talking about gender in broadcasting is pretty sad.

“There are plenty of qualified people who can do a game. Debbie has been doing it a long time. Anyone who knows her sees her work ethic and her ability to call a game, someone who has done her homework … I’m proud of her career. She’s earned it.

“She also has a beautiful family — and it’s very challenging for a women to devote this much time to the game as a man does, but she has walked that tightrope.

“But just because it’s a ‘woman’ who is doing this, again, it shouldn’t be a big deal. I wish this was much more of a common thing.”

Who else wore No. 15 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

Shawn Green, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (2000 to 2004):

The former Tustin High standout who set a CIF record with 147 hits during his prep career remains the Dodgers’ franchise leader with most homers in a single season — 49 in 2001, to go with 125 RBIs and 20 stolen bases to finish sixth in the MVP voting. The next season, he hit 42 homers (and was an All Star pick and fifth in the MVP voting). That means the 91 homers over a two-year stretch is also more than anyone’s ever done in team history (as Duke Snider was next hitting 85 in 1955 and ’56). Green’s four homer game in Milwaukee on May 23, 2002 not only tied the MLB record but set a mark with 19 total bases in his 6-for-6 day that also included seven RBIs and six runs scored (and his average went from .238 to .265 in one day, and then jumped to .282 three days later as he had a four-game stretch of going 14 for 19 with seven homers). Green also made news during the 2001 season. On September 26, he sat out a game for the first time in 415 games, to honor Yom Kippur.

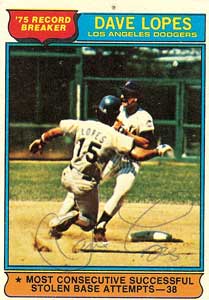

Davey Lopes, Los Angeles Dodgers second baseman (1972 to 1981):

He didn’t reach the major leagues until age 27, and was sixth in the NL Rookie of the Year voting at age 28 when he was given a spot in the starting lineup at second base but ended up playing shortstop, third, center field and right field. His stolen base totals of 77 and 63 led the NL in ’75 and ’76, setting an MLB record in ‘75 for most consecutive successful steals attempts with 38. He had a string of four straight NL All-Star selections from ’78 to ’81, covering three of the team’s NL pennants (and the ’81 World Series, afterwhich he was dealt to Oakland). He stole 418 of his career 557 bases as Dodger in his 10 years as part of the heralded infield of Garvey-Lopes-Russell-Cey. He also managed the Milwaukee Brewers from 2000 to ’02.

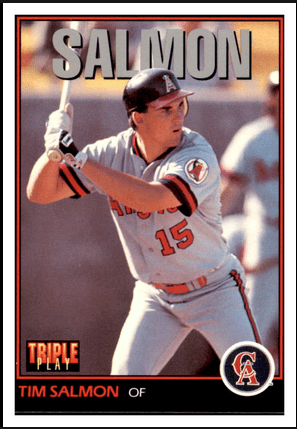

Tim Salmon, California/Anaheim/Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim outfielder (1992 to 2006):

Before Trout, Salmon was the big fish in the little pond of Anaheim. His 14 years of service, spanning three franchise names, started with the AL Rookie of the Year in ’93 (31 homers, 95 RBIs, .283 average), included a Silver Slugger in ’95 (.330 average with a career-best 34 homers and 1.024 OPS) and ended one homer short of 300. Here’s the thing: In his very last game — Oct. 1, 2006, batting third as the DH — Salmon was in the on-deck circle in the bottom of the 10th inning as his team trailed 11-10 and he didn’t get one last swing at it as Reggie Willits popped out to first to end the game, the season, and Salmon’s career. His career was curiously never was worthy of an AL All-Star selection (see: Karros, Eric; Los Angeles Dodgers) even as he hit .346 in the 2002 World Series, going 9 for 26 with two homers and five RBIs (1.067 OPS). The same year he was honored with the MLB Hutch Award for the player who best exemplifies the fighting spirit and competitive desire of the late Cincinnati Reds manager Fred Hutchison.

Laiatu Latu: UCLA football defensive lineman (2022 to ‘23):

The Bruins’ first ever winner of the Lombardi Award, the Ted Hendricks Award and the Polynesian Defensive Player of the Year honor, as well as the Pac-12 Pat Tillman Defensive Player of the Year award, led the nation in tackles for loss per game (1.8) and was fourth nationally in sacks per game (1.8), compiling 13 sacks to go with two interceptions. His two seasons at UCLA came after starting off as a linebacker at the University of Washington. He was a first-round pick of the Indianapolis Colts in 2024.

Ryan Getzlaf, Anaheim Ducks center (2006-07 to 2021-22):

The 17 seasons that “Captain Clutch” amassed for the franchise actually began a year earlier when the 20-year old sported No. 51 for the Mighty Ducks of Anaheim in 2005-06, a year after he (and everyone else) had to sit out because of the NHL lockout. He was a 21-year-old 25-goal scorer during their ’06-’07 Stanley Cup run. Consistently gaining votes as an All Star and for the Byng, Hart and Selke Award, Getzlaf amassed a 91-point season in ’08-09 and topped the 30-goal mark in ’13-’14 when he was runner-up to Pittsburgh’s Sidney Crosby for the Hart Memorial MVP Trophy. He retired as the franchise leader with 1,019 points in 1,157 games and a plus-102 rating. It’s also noted that he’s one of the rare NHL players who was captain of a team for 10 seasons and also scored more than 1,000 points with the same team.

Darryl Evans, Los Angeles Kings left wing (1981-82 to 1984-85):

He scored the game-winning goal on the 1982 Miracle on Manchester. With the Kings down 5-0 in the third period of a home playoff game at the Forum in Inglewood, they chipped away at Edmonton’s lead and tied the game with five seconds left in regulation. At 2:35 of the extra period, Evans, then a rookie, blasted the puck, beating Grant Fuhr, a future Hall of Fame netminder. “I think the moment still resonates today because of a couple of things,” said Evans, who led the Kings in playoff scoring with 13 points. “One, the opposition being the Wayne Gretzky-led Oilers that finished 46 points ahead of the Kings that year, and, two, the deficit of five goals entering the third period. No other team in Stanley Cup playoffs had ever come back from.” That, and the fact he’s remained on the Kings’ radio and TV broadcasts for the greater part of the last few decades, ought to guarantee he never has to buy a drink again in Southern California.

Chris Kontos, Los Angeles Kings left wing/center (1987-88 to 1989-90):

After Darryl Evans departed, Chris Kontas picked up the playoff magic wand against Edmonton. Kontos, who started with No. 33 when he came to L.A. from Pittsburgh mid-season in ’88, scored a couple of goals and had 10 assists (including five in one game) during eight appearances. In a 4-1 playoff series loss to Calgary, he had one more goal and went off to play in Switzerland.

Returning as a free agent at the end of the ’88-’89 season with No. 15, Kontos had eight goals in seven games — with a playoff record six on the power play — as the Kings, with Wayne Gretzky, upset the defending Stanley Cup champion Edmonton in the first round. He had a hat trick in Game 2 against Grant Fuhr, scoring once in each period. In Game 5 with Edmonton up 3-1, Kontos scored the Kings’ first goal in what would be a 4-2 win over Fuhr. In Game 7, Kontos scored on the power play in the first period to send the Kings off to a 6-3 win. Kontos’ eight goals were twice as much as Gretzky had in the series, and they came on 24 shots. In the Smythe Division final against Calgary. Kontos’ second-period goal gave the Kings a 2-1 lead in Game 1, but they would lose 4-3 in overtime, and the Flames pull off a four-game sweep. In 11 games that postseason, six of Kontos’ nine goals were on the power play. So what happened the next season? “Don’t really want to get into the politics in hockey, but once again being demoted to Phoenix at the beginning with a new contract and a newly hired coach was not a good situation,” Kontos once explained. “I regretted signing with the Kings after coach Robbie Ftorek had been a big part of me getting my first and second crack at playing in L.A.” Kontos played in just six regular season games in ’89-90 (two goals, two assists).

Vince Ferragamo, Los Angeles Rams quarterback (1977 to 1984):

Born in Torrance, an All-American at Banning High in Wilmington and the L.A. City Player of the Year went through Cal and Nebraska before the Rams took him in the fourth round of the 1977 draft. As Pat Haden’s primary backup for two seasons, Ferragamo vaulted into the starting role in 1979 because of Haden’s broken finger and got the Rams to a 9-7 regular-season record, plus wins over Dallas and Tampa Bay in the playoffs. That landed him a starting rule on Super Bowl XIV in Pasadena — making him the first quarterback to start a Super bowl in the same season as his first career start. The Rams led after three quarters before losing to Pittsburgh, 31-19. Ferragamo didn’t give up the starting rule in 1980, throwing for 30 touchdowns (tied for the league lead) and an 11-4 record, but they lost in a wild-card game to Dallas. Ferragamo then jumped to the Canadian Football League for one season, but was back with the Rams for ’83 and ’84 — the later of which he led the NFL with 3,276 yards passing to go with 23 picks against 22 TDs.

John Sciarra, UCLA football running back/quarterback (1972 to 1975):

Seventh in the ’75 Heisman vote, he moved from running back to quarterback after his freshman season. By the time he moved onto the NFL and CFL, he was playing safety and wide receiver. The CIF Southern Section high school baseball player of the year at Bishop Amat, Sciarra was tempated to play pro baseball before committing to UCLA, where he was a consensus All-American in ’75, then named the MVP of the Rose Bowl as UCLA upset favored and No. 1 Ohio State, 23-10. The team captain and two-time team MVP led UCLA in scoring in 1975, and he also led the Bruins in punt return yardage in 1972 and 1973. Sciarra holds the school record for rushing yards gained by a quarterback with 1,813, and he still ranks ninth in career total offense (4,464 yards) and 14th in career passing yards. Sciarra was inducted into the UCLA Athletics Hall of Fame in 1994, and College Football Hall of Fame in 2014.

Terry Baker, Los Angeles Rams quarterback/running back (1963 to ’64)

In the 1963 NFL Draft, the Rams made the Heisman Trophy winner from Oregon State the No. 1 overall choice after he threw for 3,476 yards and 23 TDs and led the Beavers to a 9-2 mark. The left-handed thrower only got into four games as a Rams rookie, starting one, competing with Roman Gabriel and Zeke Bratkowski. Baker’s most impressive stat: A 5.1 rushing average. So, they switched him to tailback, and he had more yards receiving than rushing in his four appearances. Switching to No. 11 for the ’65 season, he started three games, posted three touchdowns, and left for Edmonton of the Canadian Football League.

Mike Stanton, Notre Dame of Sherman Oaks baseball player (2005 to 2006):

Before he became an MLB All Star, Giancarlo Cruz Michael Stanton was a 6-foot-5, 215-pounder born in Panorama City and whose athletic career in the San Fernando Valley was one of the most dominant ever. Raised in the Tujunga area of L.A., he first went to Verdugo Hills High for two years and transferred to Notre Dame of Sherman Oaks. A receiver and cornerback on the football team who also punted, Stanton caught 29 passes for 745 yards and 11 touchdowns as a senior (wearing No. 14) A forward on the basketball team averaging 21 points a game (wearing No. 24). An outfielder for the baseball team who hit balls father than many had seen in a teenager. He was a .200 hitter as a junior, No. 7 in the batting order, not exactly the stuff that impresses college coaches or Major League Baseball scouts. But at Blair Field in Long Beach before some MLB scouts in the summer of 2006 in the Area Code Game, Stanton began launching balls onto the golf course. Baseball America wrote: “Sherman Oaks, Calif., product Mike Stanton offers intriguing upside. He had little trouble clearing the left-field wall in batting practice. The athletic, strong 6-foot-5, 205-pound Stanton generates above-average bat speed and has plus raw power.” A football offer to play for USC hung in the balance as well as a baseball offer to play at Tulane before he went into the 2007 MLB draft, a second-round pick by Miami. To come full circle, Stanton was the MVP of the 2022 All Star Game played at Dodger Stadium.

Have you heard this story:

SJ Madison, Redondo High basketball (2023-24 to 2025-26):

Martin, who wears No. 15 for the Redondo High boy’s basketball team, just did it in 2025: He got onto a billboard that sits on Pacific Coast Highway just a block north of the high school campus as part of a new Nike ad campaign/refresh featuring local prep standouts. Highly visible day or night. Just part of the new NIL era. The 6-foot-5 guard/forward who helped Redondo (28-6) to the CIF-SS Division I final against Sierra Canyon as a junior was an early commitment to the University of Nevada Reno and coach Steve Alford.

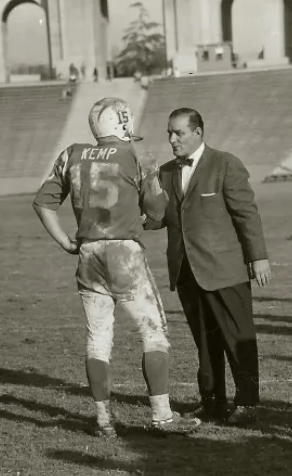

Jack Kemp, Los Angeles Chargers quarterback (1960):

He played four games for Pittsburgh’s Steelers at age 22 in 1957, but returned to the new American Football League with the Los Angeles Chargers, starting 12 games and posting a 9-3 record. The team moved to San Diego and he continued as the starter, but he became more known for his seven years in Buffalo. Occidental College has named its football field after the alum, where a statue of him also stands. Occidental football’s program was canceled in 2020.

Oh, and he went on to be a congressman, presidential candidate and was the Republican vice presidential nominee on the ticket with Bob Dole in 1996.

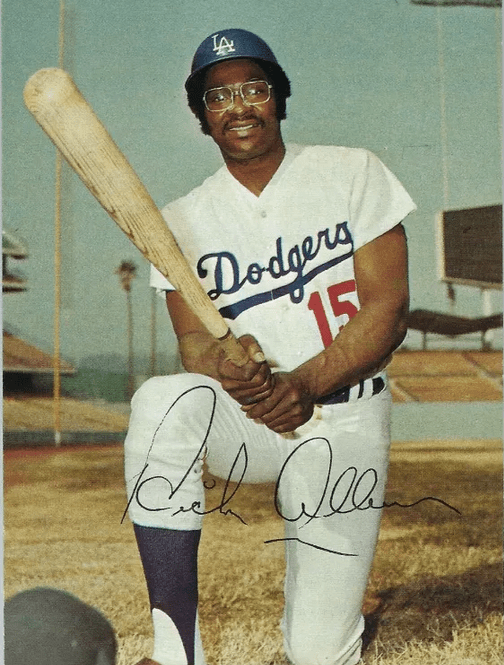

Rich Allen, Los Angeles Dodgers third baseman (1971):

His only season in L.A. seemed to be part of a transitional branding idea, going away from Richie (when he was the 1964 NL Rookie of the Year) and then embracing Dick (when he became the 1972 AL MVP). His brief but productive stay for the ’72 Dodgers: A team-best 23 homers and 90 RBIs plus a .295 average (second to Willie Davis’ .308). He was the team’s answer to a quick power fix, acquired from St. Louis after the ’70 season for for infielder Ted Sizemore and catcher Bob Stinson in what the Dodgers referred as a “bombshell deal of the off season” to get “one of the greatest sluggers of modern baseball” (see their annual yearbook page below). “Controversial or not, there’s no getting away from Allen’s devistating bat.”

But in ’74, Allen was traded to the White Sox for Tommy John, Steve Garvey moves into third base, Frank Robinson became the cleanup hitter and … Allen had a AL leading leading 37 home runs, 113 RBI, .603 slugging percentage and .420 on-base percentage to go with a .308 batting average.

It’s still baffling why he only lasted that one year, except for the obvious fact he didn’t get along with Dodgers manager Walter Alston, and that was that for the player often labeled as an outspoken troublemaker. Allen was enshrined in the Baseball Reliquary’s Shrine of the Eternals in 2004, and was there that day in Pasadena to receive the accolades. After several passes by veterans committees, he was finally given a pass into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2024. Four years after his death.

Jose Lopez, Los Angeles Galaxy forward (1974 to 1976): A teammate of George Best with the short-lived North American Soccer League team, and a member of the ’74 league title team, Lopez was the first Mexican-American inducted into the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 1993 as the captain of three teams that made it to the NCAA title game. Lopez also played three years on the Bruin baseball team and was a placekicker on the 1969 freshman football team. Then, he was the varsity baseball coach at Santa Monica High when Charlie Sheen played.

Austin Reeves, Los Angeles Lakers guard (2021-22 to present): What again is Lemondaddy.com, and why is he up on its billboard?

We also have:

Ted Kluszewski, Los Angeles Angels outfielder (1961)

Metta World Peace/Ron Artist, Los Angeles Lakers (2010-11 to 2012-13). Also wore No. 37 from 2009-10 and 2015-16 to 2016-17.

Juda “Whitey” Widing, Los Angeles Kings center (1969-70 to 1970 to 1976-77)

Davey Johnson, Los Angeles Dodgers manager (1999 to 2000)

Sandy Amoros, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (1959 to 1960)

Ernie DiGregorio, Los Angeles Lakers guard (1977-78)

Craig Fertig, USC football quarterback (1962 to 1964)

Elaine Youngs, UCLA women’s volleyball outside hitter (1989 to 1993)

Anyone else worth nominating?

2 thoughts on “No. 15: Ann Meyers Drysdale”