This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 33:

= Lew Alcindor: UCLA basketball

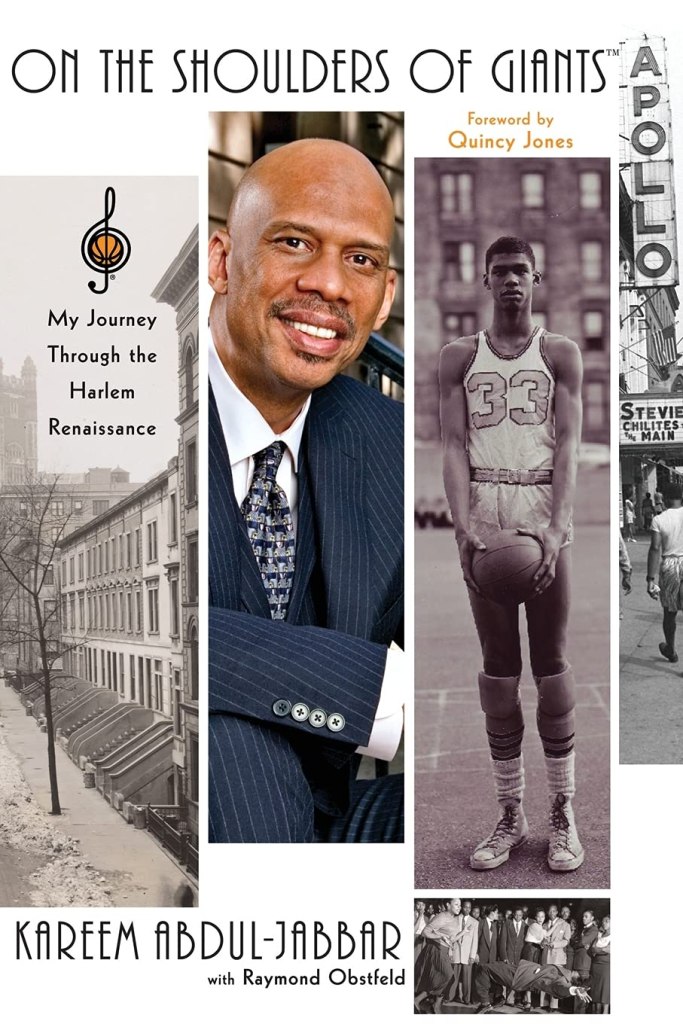

= Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: Los Angeles Lakers

= Marcus Allen: USC football

= Kermit Alexander: UCLA football

= Willie Naulls: UCLA basketball

= Marty McSorley: Los Angeles Kings

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 33:

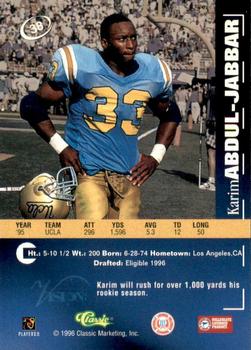

= Karim Abdul-Jabbar: UCLA football

= Lisa Leslie: Morningside High and UCLA basketball

= Charles White: Los Angeles Rams

= Ollie Matson: Los Angeles Rams

= Eddie Murray: Los Angeles Dodgers/California Angels

= Hot Rod Hundley: Los Angeles Lakers

The most interesting story for No. 33:

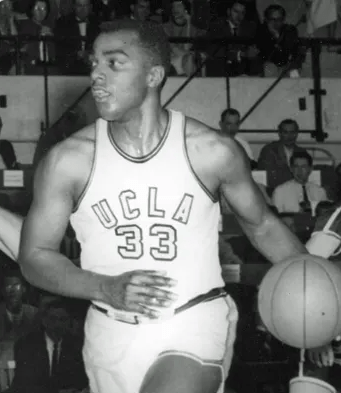

Lew Alcindor: UCLA basketball center (1966-67 to 1968-69)

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: Los Angeles Lakers center (1975-76 to 1988-89)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Westwood (UCLA); Los Angeles (Sports Arena); Inglewood (Forum)

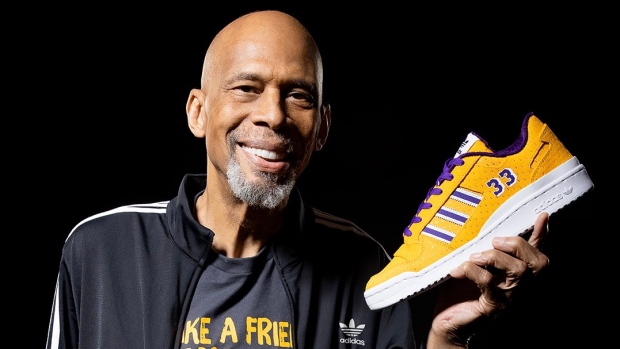

Thirty-three years after his NBA retirement, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar unfolded himself from a court side seat at the Los Angeles Lakers’ Crypto.com Arena, adjusted the black Adidas jacket he was wearing with the words “Captain 33” stitched on the front, and walked over to an area where he was supposed to wait near center court until he was needed.

The 75-year-old had made it to Feb. 7, 2023 in an upright position — nothing guaranteed in a life that saw him battle leukemia as well as a recent diagnosis of atrial fibrillation. The all-time regular-season points total of 38,387 that Abdul-Jabbar amassed during 20 record-breaking seasons in the NBA, the last 14 of them as the Lakers’ center and captain, had just been eclipsed by LeBron James, a current Lakers’ employee.

After the rush of embracing teammates, friends and family on the other side of the court, James made his way over to Abdul-Jabbar, who patiently watched, and waited. He knew this drill.

On April 5, 1984, in of all places Las Vegas, Abdul-Jabbar took a pass from teammate Magic Johnson on the baseline, faked right, turned left, and nailed an arching 11-foot sky hook shot. That gave Abdul-Jabbar 31,422 points, pushing him past another former Lakers center, Wilt Chamberlain, as the NBA”s all-time points leader. Abdul-Jabbar would have five more seasons to add to that total.

On that occasion, Chamberlain wasn’t present. He had died four years earlier at age 63, but Abdul-Jabbar’s parents were there. When Abdul-Jabbar left the NBA in 1989 at age 42, no player had ever scored more points, blocked more shots, won more Most Valuable Player Awards, played in more All-Star Games or logged more seasons. He also owned eight playoff records and seven All-Star records.

If this LeBron James moment was supposed to be a symbolic passing of the torch of greatness, there were enough sports scribes, scholars and sermonizers to point out the need for more context as this reshuffling of places on a career points list took place.

The New York Times’ Kurt Streeter wrote a piece headlined “Kareem Abdul-Jabbar is Greater Than Any Basketball Record” that remembered all the giant shoulders that were needed for this moment to happen:

“It is easy to forget now, in today’s digitized world where week-old events are relegated to the historical dustbin, how much of a force Abdul-Jabbar was as a player and cultural bellwether. How, as the civil rights movement heated to a boil in the 1960s and then simmered over the ensuing decade, Abdul-Jabbar, a Black man who had adopted a Muslim name, played under the hot glare of a white American public that strained to accept him or see him as relatable.

“It is easy to forget because he helped make it easier for others, like James, to trace his path. That is what will always keep his name among the greats of sport, no matter how many of his records fall. Guided by the footsteps of Jackie Robinson and Bill Russell, Abdul-Jabbar pushed forward, stretching the limits of Black athlete identity.

“He was, among other qualities, brash and bookish, confident and shy, awkward, aggressive, graceful — and sometimes an immense pain to deal with. He could come off as simultaneously square and the smoothest, coolest cat in the room.”

The Los Angeles Times’ Bill Dwyre, in an essay headlined “Kareem Abdul-Jabbar will always be No. 1 for his post-NBA career work,” added:

“During Barack Obama’s presidency, Abdul-Jabbar was called to Washington to receive a Medal of Freedom. This goes to world figures of importance, thinkers of depth and substance, people whose life and existence have inspired and influenced. We are blessed that Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was all of that, and that those 38,387 points were only a part of who he was. And still is.”

Richard Lapchick, president of the Institute for Sport and Social Justice, ended his piece for ESPN.com under the headline “Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s lifetime as a social justice champion is a record no athlete will break” with the thought: “Thank you, Kareem, for all you have done for 60-plus years to help the United States focus on social justice. You are now the leader.”

That leadership role incubated within a man first known as Lew Alcindor. It was a result of being at the right place at the right time — UCLA, in the 1960s, when changes were happening — that he could be a true center of attention and influence.

He took the role seriously and paid some price for that.

The college story

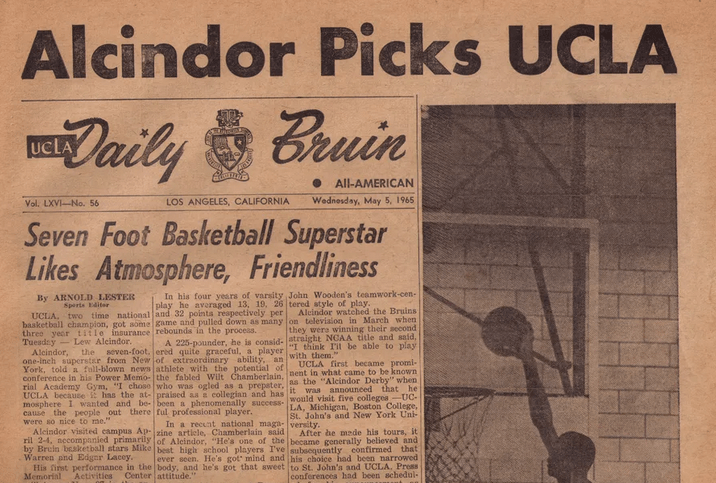

The student body at UCLA specifically, and most of Southern California basketball followers in general, knew of Lew Alcindor as the “Tower of Power” playing at New York’s Power Memorial High long before he even arrived on the Westwood campus.

The Associated Press described him as “a towering and talented youngster who is the most celebrated schoolboy basketball star ever developed in this teeming hotbed of basketball … There is no doubt the lean, agile center is a prize catch — a sure-bet standout and drawing card at any college.”

Power Memorial had just won 71 in a row and had a 79-2 record with three NYC Catholic School titles. UCLA Coach John Wooden just engineered his first two national championships in 1964 and ’65 on teams focused around local sharp-shooting kids.

Alcindor, who would grow to 7-foot-2 in Westwood, took things to new heights.

“I think I’ll be able to play with them,” Alcindor said when asked why he picked UCLA after he just watched the Bruins win another title.

He had to leave his native street-gritty New York city for a scholastic life in Los Angeles, and he agreed to do it based, in part, on the groundwork Jackie Robinson laid deciding to go to the school near his family home in Pasadena. Even if it was for a brief time. Robinson and the Brooklyn Dodgers were Alcindor’s favorite team growing up.

When a player like James could jump straight from high school to the NBA as he did as a 19-year-old in 2003, Alcindor’s path 50 years earlier not only prohibited that sort of leap past the college game, but college made a rule that prevented freshman from playing on the varsity team. A college career was three seasons, then graduation.

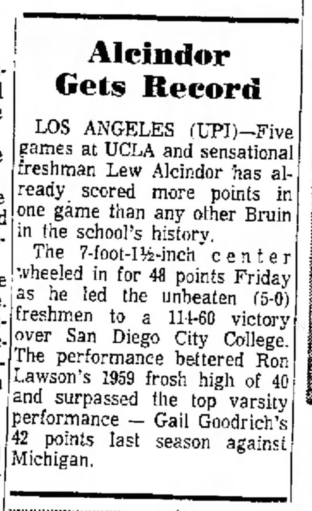

As such, Alcindor and nine other recruits made up a team called the “Brubabes” for the 1965-66 season. The first thing that group did under coach Gary Cunningham was defeat Wooden’s UCLA varsity team and defending NCAA champs, 75-60, during a scrimmage at Pauley Pavilion. Alcindor had 31 points and 21 rebounds.

Those were his points and rebounding game averages he had during the freshman team’s 21-0 season, with an average margin of victory about 54 points. In the fifth game of the season, as a team of future varsity standouts including Lucius Allen, Lynn Shackleford and Kenny Heitz pounded San Diego City College, Alcindor scored 48 points, the most by anyone to ever wear a UCLA uniform. Meanwhile, the UCLA varsity may have started as the pre-season No. 1 team, dropped to No. 10 by early January, and fell out of the rankings all together in an 18-8 finish, second in the conference. Junior forward Mike Lynn, one of the tallest players on the team at 6-foot-7, averaged 16.8 points and 10.3 rebounds to lead the varsity, along with sophomore guard Mike Warren (16.6 points a game)

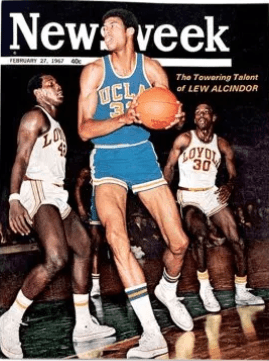

Alcindor’s emergence for the 1966-67 season was dramatic. Not just because the team went 30-0, ranked No. 1 from start to finish, defeating Dayton by 15 points in the title game behind Alcindor’s 20 points and 18 rebounds. Alcindor was one of eight sophomores and Warren was on of five juniors that made up the roster. Alcindor’s 29 points a game average, nearly twice as much as Allen’s 15, would be the greatest in any of his three UCLA varsity seasons.

A few months after the Bruins’ title game win, in what was called the Cleveland Summit of 1967, Alcindor was the youngest invitee of 12 leading Black athletes called together for a meeting to support Muhammad Ali’s decision not to serve in the U.S. military during the Vietnam War.

Alcindor got a front-row seat for a real-life lesson in civics. Two weeks later, Ali, who went by Cassius Clay and changed his name to reflect his new Muslim beliefs, was found guilty of draft evasion and exiled from boxing for three years. The Supreme Court reversed the decision in 1971.

That experience led to Alcindor declining a spot on the U.S. Olympic men’s basketball team for the ’68 Games in Mexico City.

By that point, Alcindor had changed the game, and the playing field. A new NCAA rule outlawed the dunk in college, decreeing there was a concern of increased injuries. It just meant Alcindor had to create a new scoring weapon — the sky hook. The no-dunk rule would stay into effect only until the 1976-77 season, shortly after Wooden’s retirement.

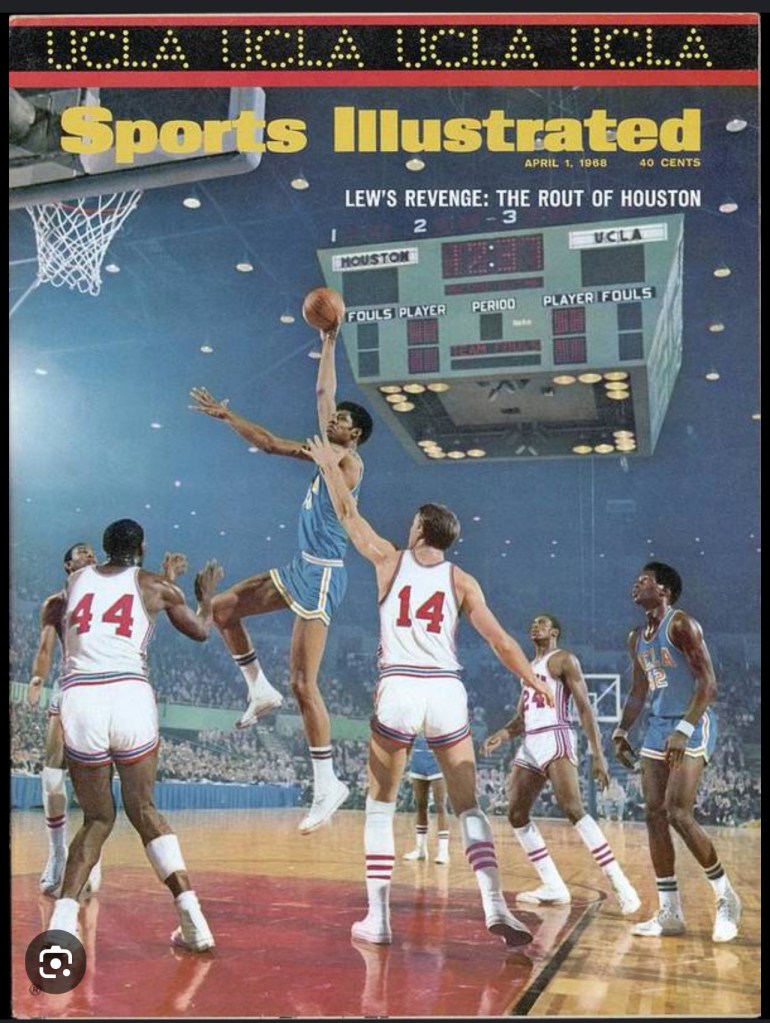

In Alcindor’s junior season, the only blemish in a 29-1 run was another historic event, a widely-watched contest at the wide-open Houston Astrodome on Jan. 20, 1968 when the No. 1 Bruins fell to No. 2 Houston and Elvin Hayes, 71-69. Alcindor had 15 pounds, 12 rebounds and three blocks despite a UCLA ophthalmologist diagnosis that Alcindor suffered from double vision and impaired depth perception at the time because of an injury.

In the NCAA national semifinals at the L.A. Sports Arena, UCLA avenged the loss to then No. 1 Houston as Alcindor had 19 points and 18 rebounds and held Hayes to 10 points and five rebounds in a 101-69 triumph. Two nights later, UCLA posted a 23-point win over North Carolina in the NCAA final, led by Alcindor’s 20 points and 18 rebounds.

One more misstep from perfection happened in Alcindor’s final season of 1968-69. A 46-44 loss to USC in the final game of the inaugural Pac-8 schedule also ended a 51-0 run that that Bruins had since the opening of Pauley Pavilion. One night earlier, UCLA needed double overtime to outlast USC, 61-55, at the L.A. Sports Arena. The Trojans implemented an offensive stall against the Bruins’ zone defense, exploiting a notable loophole in the rules.

In the Final Four, UCLA’s three-point semifinal win over Drake saw Alcindor score 25 points (almost a third of the Bruins’ total) and take 21 rebounds (half their team total). Alcindor’s 37-point, 20-rebound game in a 20-point win over No. 6 Purdue in the NCAA title game in Louisville, Ky., marked his final collegiate game.

The check list of Alcindor’s resume to this point as he headed toward a pro career:

= An 88-2 varsity record (on top of that 21-0 freshman team) and a 12-0 in the post season leading to three NCAA titles. That constitutes 121 wins and two losses by four total points.

= The greatest scoring average in school history (26.4 a game), to go with a school record in field goals (943) and most points in a season (870 as a sophomore in 30 games).

= Most points scored in a single UCLA varsity game (61, against Washington State on Feb. 25, 1967, which remains tied as a conference record and is in the NCAA Top 20 of all time). He also had the most points in NCAA history for someone playing in their first college varsity game (56 points).

= Three times the Final Four Most Outstanding Player. Eventually named to the NCAA Tournament All-Time Team and one of the Top 15 players in NCAA Tournament history during a 75 Years of March Madness Celebration.

= The first ever Naismith College Player of the Year in 1969.

If he needed a letter of recommendation, Wooden summed it up:

“He’s a remarkable young man, forgetting his basketball, he’s remarkable. For instance, he can discuss three or four religions quite intelligently. How many of us can do that? I can’t. He reads a lot, particularly philosophy. He’s a very intelligent youngster.”

The professional story

At the April 7, 1969 NBA Draft in New York, the Milwaukee Bucks won a coin flip against the Phoenix Suns to land the first overall choice. That’s how it was done. Alcindor had some leverage: A $1 million offer to join the Harlem Globetrotters, and a $3.25 million contract offered by the New York Nets of the fledgling American Basketball Association, in its third season of operation.

Three months earlier, Joe Namath spurned the NFL and led the American Football League’s New York Jets to a huge Super Bowl III upset. The Alabama quarterback had been the 12th pick overall by St. Louis in the 1965 NFL Draft, but he took up the Jets’ offer for a $200,000 deal and a new Lincoln Continental. He became Broadway Joe.

Ferdinand Lewis Alcindor, Jr., decided to be Midwest Loner Lew, taking the Bucks and their $1.4 million offer. He lasted six seasons in Milwaukee and, between the ages of 22 and 28, won three three MVP Awards, two scoring titles (including 34.8 points a game in 1971-72, seventh-best all-time) and the 1970 Rookie of the Year.

After the Bucks won the 1971 championship, the first for a Western Conference team in 12 seasons, Alcindor and new teammate Oscar Robertson went on a three-week tour of Africa on behalf of the state department. When he came back in June, ’71, Alcindor declared he wanted to be known by his Muslim name, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, which translated to “noble one, servant of Allah.” It was a name he actually took that name in the summer of 1968, converting from Catholicism.

The name wasn’t a big branding tool for him in Milwaukee. He was named to the ’73 All Star team but skipped it for personal reasons. To start the ’74-’75 season, he injured his eye in the preseason and started wearing goggles. He made overtures of wanting a trade to either New York or Los Angeles. Finally, the Bucks, who finished 1975 with a 38-44 record, accommodated him.

In June of ’75, the Lakers, who just went 30-52 to finish fifth in the Pacific Division, stepped up by sending rookies Dave Meyers and Junior Bridgeman, veteran center Elmore Smith, guard Brian Winters and cash to the Bucks for Abdul-Jabbar, along with his backup center, Walt Wesley. The gap that the Lakers had experienced between their last NBA title with Chamberlain and West in 1972 now felt as if a new garden had been reseeded.

Abdul-Jabbar’s first season back in L.A. was dominating: 27.7 points a game, leading the league with 16.9 rebounds a game, and a fourth MVP award, the first ever for a Laker in NBA history, even though the Lakers were 40-42, fourth in the Pacific Division. The next season of ’76-’77 was another MVP Award (26.2 points, 13.2 rebounds, 3.9 assists), even though his Lakers, winners of the Pacific Division at 53-29, were swept in the Western Conference finals by Bill Walton’s Portland Trailblazers.

The start of the ’77-’78 season saw 30-year-old Abdul-Jabbar miss almost two months with a broken hand, the result of punching Bucks center Kent Benson two minutes into the opening game in Milwaukee, after Benson hit him with a right elbow to the stomach (no foul was called, and Abdul-Jabbar needed a few moments to compose himself before he delivered his own message).

“I decided if I could get my breath back, he was going to pay. It was a frightening experience for me because that’s when I realized I better control my temper at all times, no matter what the provocation. I could’ve killed him. Thinking about that really bothered me,” Abdul-Jabbar said a few years later.

Abdul-Jabbar was ejected (Benson left was well with a swollen eye), fined a league-record $5,000 but wasn’t suspended, and went back to his hotel room to watch the Dodgers lose to the New York Yankees in Game 6 of the World Series. Abdul-Jabbar also was not included in the All Star for the first and only time in his 20-year career. Abdul-Jabbar responded to the snub by scoring 39 points with 20 rebounds in a win over Philadelphia the day after the rosters were announced. He put up a 37-point, 30-rebound game over New Jersey in the last game before the All-Star recess.

The Lakers’ acquisition of Magic Johnson as the No. 1 overall pick in 1979 changed the complexion of the franchise, and Abdul-Jabbar’s status with the team as the Showtime dynasty began. Abdul-Jabbar’s greatest contribution to the 1980 Finals perhaps was magnified by missing Game 6 with an ankle injury, allowing Johnson to jump center, put on one of the game’s most incredible performances, and close out the title in Philadelphia.

For six more seasons, Abdul-Jabbar poured in an average of 20 points or more and the Lakers rattled off titles in 1982, ’85, ’87 and ’88. Abdul-Jabbar has said that the 1985 championship may have been the sweetest of his six, won at the Boston Garden and reversing an historic trend of the Celtics’ hold over the Lakers. In that series, the 38-year-old was thought to be past his prime — he had only 12 points and three rebounds against Robert Parish and the Celtics’ opening game 148-114 win was known as the “Memorial Day Massacre.” In Game 2, Abdul-Jabbar scorched the Celtics with 30 points, 17 rebounds, eight assists and three blocked shots in a 109-102 Lakers win. The Lakers won the series in six games and Abdul-Jabbar was the Finals MVP, putting up 30.2 points, 11.3 rebounds, 6.5 assists and 2.0 blocks a game in the four wins. In one memorable sequence, Abdul-Jabbar grabbed a rebound, drove the length of the court and converted a sky-hook.

When he suited up for his 17th season in 1985-86, Abdul-Jabbar set a record for most seasons played in the NBA. After Game 7 of the ’88 Finals, he announced he would come back for one more season, which led to a retirement tour of gifts and ovations. Even in his last NBA Finals appearance, as the injured Lakers were swept by Detroit, Abdul-Jabbar had a season-high 24 points and 13 rebounds in Game 3.

Several years after he retired, Abdul-Jabbar told the Orange County Register: “The ’80s made up for all the abuse I took during the ’70s. I outlived all my critics. By the time I retired, everybody saw me as a venerable institution. Things do change.”

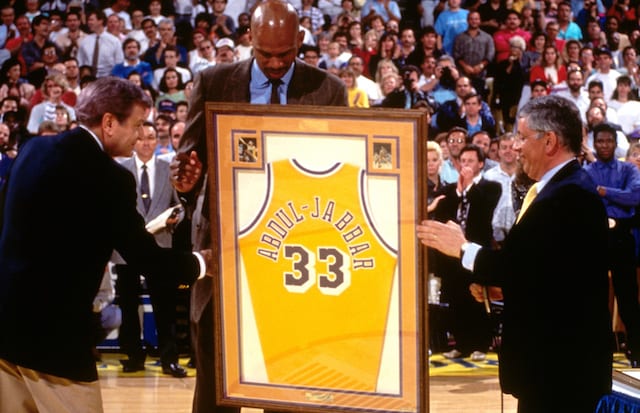

The check list of Abdul-Jabbar’s resume as his days wearing No. 33 were done:

= Six NBA titles (five with the Lakers in a nine-season span of ’80, ’82, ’85, ’87 and ’88) and an appearance in the Finals in ’83, ’84 and ’89 for the Lakers.

= Six MVP Awards (three with the Lakers in ’76, ’77 and ’80).

= Two-time scoring champion; one-time leader in rebounds and four-time leader in blocked shots.

= 19-time NBA All Star selection.

= 15-time All-NBA selection, including 10 times on the first team, six of them with the Lakers.

= 1985 Sports Illustrated Sportsman of the Year

= In 1996 part of the “50 Greatest Players in NBA History” ceremony

= A statue of him outside Staples Center in 2012.

= As for another letter of recommendation for what came next, his former Lakers coach, Pat Riley, once said: “Why judge anymore? When a man has broken records, won championships, endured tremendous criticism and responsibility, why judge? Let’s toast him as the greatest player ever.”

The Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame not only rightfully inducted Abdul-Jabarr into its shrine in 1995, but since 2015 it gives out a Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Award to honor the top center in the college game.

His bio reads: The world may never again see an athlete dominate a sport for as long and as masterfully as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. … the 7-foot-2-inch cerebral center established himself as one of the game’s most talented and recognizable figures. Abdul-Jabbar’s trademark skyhook was so precise that he left defenders helpless, and the Captain’s signature move is now widely considered basketball’s most classic and lethal offensive weapon. He lofted the graceful shot over outstretched hands for the better part of four decades bringing finesse and agility to the center position, traits he substituted for brute force and strength. While scoring was the means, the end was always wins and Abdul-Jabbar won at every level during his prolific career.

The numerology

The New York Giants’ roster in the mid-to-late 1950s included stars like Frank Gifford, Don Heinrich, Kyle Rote, Rosie Grier and Sam Huff, winning the 1956 NFL title, losing in the ’58 and ’59 championship games. They also had fullback Mel Triplett, a 6-foot-1, 215-pounder out of Toledo who grinded out six seasons in New York between 1955 and 1960.

Lew Alcindor admired Triplett’s Gotham City tenacity.

“He wasn’t like a major scoring threat or anything,” Kareem Abdul-Jabbar later told NFL Films. “But he was a tough guy. I thought I could play like him, be the big running back. Of course, I was the long non-running back who ended up playing basketball.

“He wore No. 33 and that’s why I wore No. 33. In seventh grade, we got new basketball uniforms at my grade school and they had a No. 33. I picked it and from that point until the end of my career, I was still wearing No. 33.”

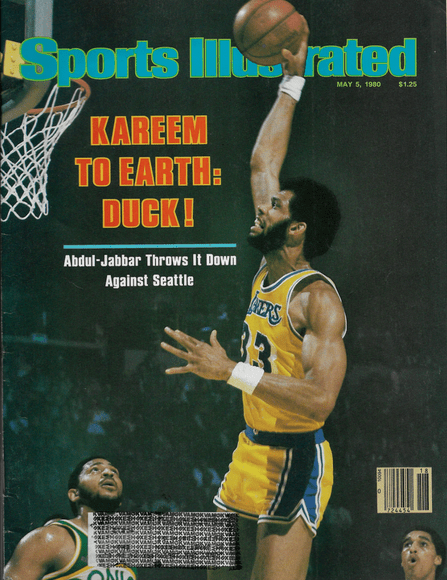

Until, somehow, he wore No. 34 on the cover of Sports Illustrated.

The Dec. 5, 1966 college basketball preview issue included Alcindor in a rare fold-out cover, calling him the game’s “new superstar.” The sophomore put on a No. 34 jersey because, as SI photographer Neil Liefer explained, for an odd reason, they didn’t have his No. 33 available.

For the 1966-67 season, No. 34 actually belonged to backup center and fellow sophomore Jim Nielsen, as Alcindor had No. 33, just as he had with the Bruins’ freshman team.

In the SI story, publisher Garry Valk felt he had to do some explaining: Alcindor’s appearance on our cover marks one of the rare times that a sophomore athlete has received such recognition. Though he has yet to play his first game in varsity competition, we believe he is the sport’s most important college performer. … The story about Lew that begins on page 40 has special interest because it is the result of the first interview granted to any sportswriter. In high school in New York and as a UCLA freshman he had turned down all requests. Actually, the photographer who took the cover portrait, Neil Leifer, was the first journalist to arrange a meeting with Alcindor. That took place at a studio in New York when Lew was home on vacation last spring. Leifer found Alcindor to be one of the most inquisitive subjects that he has ever photographed. Lew was so interested in every aspect of the camera work that soon he was functioning as photographer’s assistant as well as subject. He posed for nearly four hours, and Leifer calls him “the most cooperative athlete I have ever worked with.” Lew was equally responsive with Associate Editor Frank Deford, who met with him this fall. “He is very articulate,” Deford says, “and he expands on his answers, even when he doesn’t particularly like the question. Though he is not enthusiastic about being interviewed, he is so polite and expresses himself so well that he should always have a very good relationship with the press.”

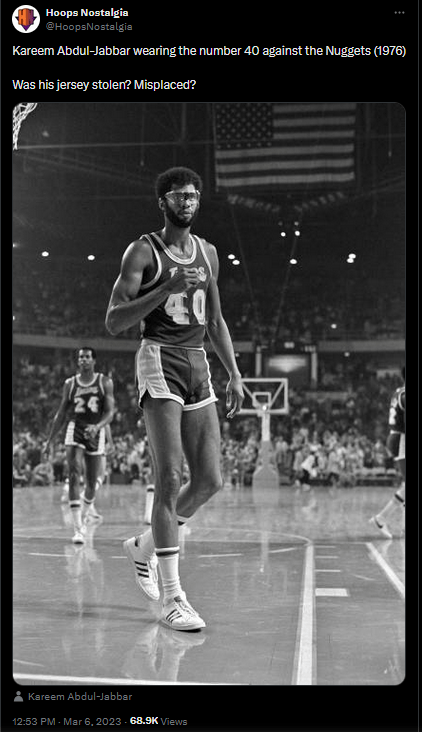

Now, how was it that on Nov. 24, 1976, for a Lakers’ game in Denver, Abdul-Jabbar had to wear a No. 40 jersey with no name on the back? Likely a lost laundry issue. He scored a game-high 28 points going up against the Nuggets’ Dan Issel, but the Lakers lost 122-112. Time to discard that old thing. Lakers who would wear No. 40 before or after that time: Jerry Chambers (1967), Dave Robish (1978-79), Mike McGee (1982-86), Sam Perkins (1993), Antonio Harvey (1994-95), Travis Knight (1997-2000) and Ivica Zubac (2017-19), who had, among his nicknames, “Zu Alcindor.”

Then, on Jan. 30, 1986, Abdul-Jabbar wore No. 50 against Chicago. They couldn’t find his No. 33 jersey. If anyone has it, maybe hang onto it.

The legacy

Aloof Lew and Cranky Kareem was eventually explained by him as the product of an only child, and he saw his father, a policeman, come home each night beaten down by the rigors of his work, and the disappointment in the way some people treated each other.

My experience as a Lakers’ ballboy was once waiting in a crowded hallway outside the Lakers’ locker room at the Forum in 1976, months after he came to the team from Milwaukee. He had a rather large entourage with him, unlike the others on that team. I had a game program already signed by the likes of Cazzie Russell, Lucius Allen, Don Ford, Johnny Newman, Don Chaney, Mac Calvin, Kermit Washington and Cornell Warner. As Abdul-Jabbar entered the hall, I spoke up.

“Kareem?”

The entire entourage, with Abdul-Jabbar, turns to look at me.

“Can you sign this for me?”

Abdul-Jabbar sighs, turns away in the other direction, and the group follows him.

At various points in his career, he tried to lighten things up. The most famous example was in the 1980 movie, “Airplane!” when he played himself hiding behind the name co-pilot Roger Mudrock for a scene that only went a minute long, but explained a lot and made me almost feel like the child actor in this moment:

In a 1985 profile Gary Smith did for Sports Illustrated on the occasion of the magazine naming Abdul-Jabbar its Sportsman of the Year, the juxtaposition of his public and private image were examined:

“The very traits that made people dislike him … were those that would make him last long enough that people would finally revere him. By not sacrificing himself for loose balls or rushing downcourt on every fast break, he conserved his body for the long haul. Because he became a Muslim, he seldom consumed alcohol or meat, and he remained remarkably fit. Because he distrusted people, he shunned parties and always got his sleep. Because he did not think and act like other people — he was practicing yoga long before stretching became accepted regime in the NBA — he kept his legs flexible and strong while other big men his age became stiff-jointed and slow. Somehow, this tall, strange man, striding up court with the big bald spot and the industrial goggles would endure long enough to demonstrate the foolishness of passing judgment too quickly.”

In 2018, Abdul-Jabbar continued to try to change his own narrative by launching a cross-country audience-interactive stage production called “Becoming Kareem,” a title that comes from his 2017 young-adult autobiography. His media image was often sullied by his own doing “and that was very unfortunate,” Abdul-Jabbar told an AP reporter from his Newport Beach foundation office. “I think it kept me from a head coaching job and commercials and stuff because people wanted to assume the worst.”

By the time the Los Angeles Business Journal started to formulate who would make its 2023 list of the LA500 — those people most influential in the city’s existence — I was asked if I had any names to suggest for any of the categories of sports figures and civic leaders. Those were the group of bios I was asked to write.

I wondered how Kareem Abdul-Jabbar had never been on either list. The editor agreed, with some disbelief, and had me include him with the civic leaders. I had only a few words to use, so it went this way:

As Esquire noted in a March 2023 story, Abdul-Jabbar “has found his second act as, of all things, a writer. Not a coach, executive, businessman, or TV blabbermouth (he’s too good a listener to be on TV).”

Abdul-Jabbar wanted to matter in the world he was living in. Not be remembered just for his abilities as a player.

“I can do something else besides stuff a ball through a hoop,” he said. “My biggest resource is my mind.”

The NBA gives out the Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Social Justice Award each since 2021. And to that point, in 2019, he sold off four of Lakers’ NBA title rings and three of his MVP trophies among more than 200 items to raise nearly $3 million to use for youth education programs.

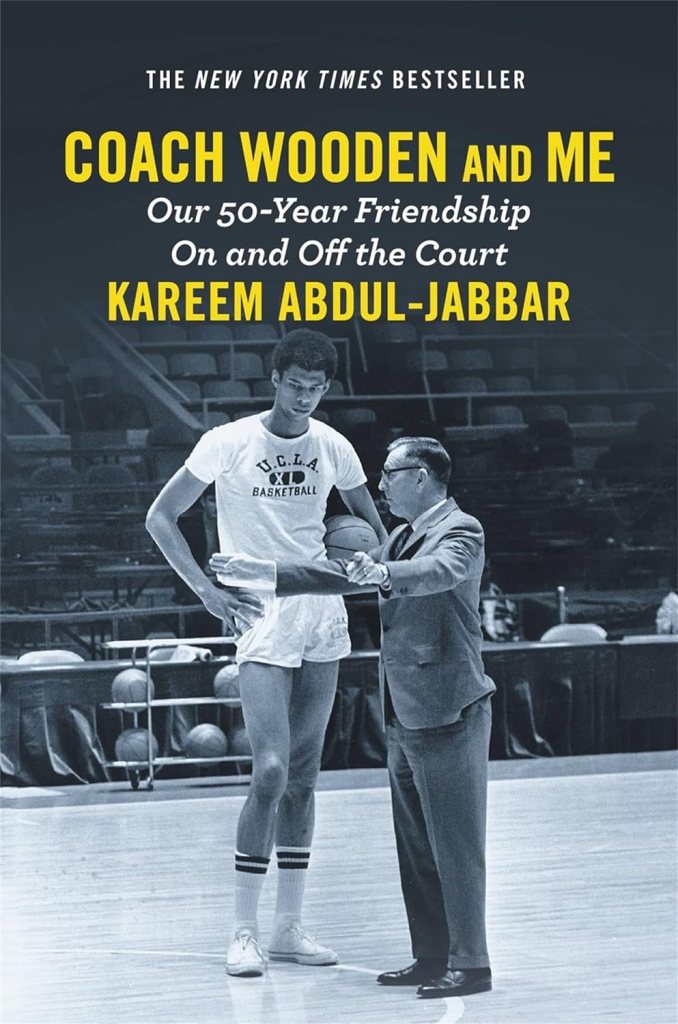

He had already written more than a dozen books, adding perspective on African Americans who fought in World War II, the lessons he learned from Wooden, his time on an Apache reservation helping coach a youth basketball team.

He was regularly commenting on the news of the day, adding context and history, trying to become some kind of Zen filter for a society somewhat bent on chaos and disruption. Time magazine, CNN and other major publications solicited his opinions.

When CBS Sunday Morning did an interview with Abdul-Jabbar about his life as a social critic, he explained:

The bottom line is Abdul-Jabbar has wanted to stay alive and vital. He has a cultural footprint. He can keep creating giant steps. Heck, he could use his own forum to explain how his days at the Forum were now being misrepresented in the HBO series “Winning Times,” calling it not just something he found “deliberately dishonest,” but worst, it was “drearily dull.”

Being around for an appearance at a Lakers’ game in 2023 when an historic moment happened wasn’t something he felt like missing.

Abdul-Jabbar wrote on his own Substack.com account — the one called “KAR33M” — that in the past, he would have hated to see his record broken. A younger and more competitive self “might have hobbled out of retirement just to add a few more points” so he could get it back.

“That ain’t me today. I’m 75. The only time I ever think of the record is when someone brings it up. I retired from the NBA 34 years ago.” He said the occasion should be a “celebration,” not based on lousy jealousy.

“It means someone has pushed the boundaries of what we thought was possible to a whole new level,” he wrote. “And when one person climbs higher than the last person, we all feel like we are capable of being more.”

Maybe those are the words that could be repeated whenever one athlete surpasses another in whatever career number is being acknowledge. In other words, say it over and over again, even if it means Abdul-Jabbar starts to sound like a broken record.

Who else wore No. 33 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

Willie Naulls, UCLA basketball (1953-54 to 1955-56):

The first player from Los Angeles to be named California’s Mr. Basketball in 1952 while at San Pedro High, Naulls became an All-American starting with the fifth team that Coach John Wooden had at UCLA. Naulls left as the program’s all-time scoring leader (1,225 points in three seasons) and leading the team in rebounding in each of his three seasons. Naulls still holds the school record for most rebounds in a game with 28 against Arizona State in January 1956. Perhaps the most influential game of his career came in 1954 when he led UCLA to a 47-40 win over heavily favored University of San Francisco, which had Bill Russell and K.C. Jones. That would be USF’s lone loss in a season it won the NCAA title. After Naulls averaged 23.6 points and 14.6 rebounds a game as a senior, he moved onto an NBA career where he joined Russell and Jones to win the championship with the Boston Celtics in 1964, ’65 and ’66 — the final three seasons of Naulls’ pro career. He became the first of many former UCLA player to win an NBA Finals. Naulls, Russell, K.C. Jones, Sam Jones and Tom Sanders also became the first all-African-American starting team in the history of integrated professional sports in Dec. 1964. Naulls, inducted into the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 1986, came back to the campus to get his degree after his NBA days were over, and he also earned a master’s in theology from Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena in 1993. In 12 NBA seasons, he was on three title teams in Boston and made four All Star teams.

Marcus Allen, USC football running back (1978 to 1981):

The 1981 Heisman Trophy winner earned the award after becoming the college game’s first to surpass 2,000 rushing yards in a season — posting 2,342 yards from scrimmage in 403 attempts (36 carries a game) and 22 touchdowns as a senior. Allen’s Heisman “moment” may have come on Oct. 30, 1981 — in No. 4 USC’s 41-17 win over No. 14 Washington State, he ran 44 times for 289 yards and four touchdowns, and would top 200 yards in eight of his 11 games while setting 14 NCAA records. Allen came to USC as a star quarterback and safety at Lincoln High in San Diego — and safety was his primary position until coach John Robinson moved him to tailback as a backup to Charles White during the team’s ’78 national title run. In ’79, Allen was moved to fullback — putting his 6-foot-2, 210-pound body on the line to open holes for White during his Heisman campaign. Allen picked up 649 yards and eight touchdowns rushing in the process. As a junior, Allen went back to tailback and posted 1,563 yards and 14 touchdowns, leading the nation in all-purpose yards. His leap into the NFL and a Pro Football Hall of Fame career started kept him in L.A. with the Raiders took him No. 10 overall (the third running back at that point behind Stanford’s Darrin Nelson to Minnesota at No. 7 and Arizona State’s Gerald Riggs to Atlanta at No. 9. Because Raiders fullback Kenny King had No. 33, Allen wore No. 32 for his 11 season with the Raiders, and five more in Kansas City.

In ESPN’s 2020 list of the 150 greatest college football players in the game’s first 150 years, Allen came in at No. 40 noting his 4,682 rushing yards, 5.2 yards per carry and 45 rushing TDs: The most difficult accomplishment of Allen’s Trojan career may have been winning the starting tailback job. He showed enough promise to make head coach John Robinson move another running back named Ronnie Lott to defense. …. (As a senior), Allen gained nearly 6 yards per rush. He beat Herschel Walker for a Heisman. Enough said.

Charles White, Los Angeles Rams running back (1985 to 1988):

The Rams traded away Eric Dickerson in Week 4 of the 1987 season. So what’s a team to do? Coach John Robinson called on his former USC tailback. White made his first and only NFC Pro Bowl appearance after he somehow led the NFL with 1,374 yards, 11 touchdowns and 324 carries. The team finished 6-9, but it could have been worse. White was named the NFL’s Comeback Player of the Year — a highlight in an eight-year pro career that started when he was the Cleveland Browns’ first-round draft pick in 1980 (27th overall) out of USC following his Heisman season (wearing No. 12).

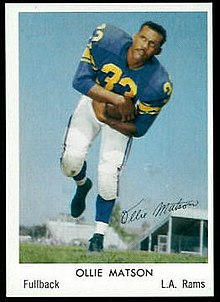

Ollie Matson, Los Angeles Rams running back (1959 to 1962):

After six All Pro seasons with Chicago Cardinals, Matson, a former Olympic silver- and bronze-award winning sprinter, made about as big a splash as possible when he came to the Rams because the team’s maverick general manager, Pete Rozelle, decided to pulled off a 10-player trade. That is, nine Rams — tackles Ken Panfil, Frank Fuller, Art Hauser and Glenn Holtzman, end John Tracey, fullback Larry Hickman, halfback Don Brown, a ’59 second-round draft choice, plus a player to be named later — for one Matson. He didn’t make it into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1972 based on his four seasons in L.A. as a fullback and flanker. But he sure made some history coming to L.A.

Willie Ellison, Los Angeles Rams running back (1967 to 1972):

On Dec. 5, 1971, Ellison broke a 15-year NFL single-game rushing record with 247 yards against New Orleans at the Coliseum, passing the 237 that Cleveland’s Jim Brown set against the Rams in 1957. It also surpassed the pro football record of 243 yards at the time that the Buffalo Bills’ Cookie Gilchrist had against the New York Jets in 1963 (although Spec Sanders had 250 yards rushing in 1947 in the All-American Football Conference). As of 2024, Ellison’s 247 yards is 17th best in an NFL game — topped by Buffalo’s O.J. Simpson in 1973 with 250 and in 1976 with 273 yards.

Marty McSorley, Los Angeles Kings defenseman (1988-89 to 1995-96):

It’s tough to believe his eight rough-and-tough seasons in L.A. as Wayne Gretzky’s personal Kevlar vest was more than twice as long as the three seasons they were together in Edmonton winning two Stanley Cups. McSorley was part of the package deal with Gretzky in the earth-moving trade to L.A. in August of 1988. Soon came the 1992-93 Stanley Cup playoffs — where McSorley led the league with 60 penalty minutes. None were as influential as the punishment he received near the end of Game 2 of the Stanley Cup Final in Montreal. I once risked asking him about the Curse of the Curved Stick in 2012 when the Kings finally returned to the Stanley Cup Final. It wasn’t really fun dealing with “McSurley” at times on this touchy subject. Not many teammates would stick up for him. On the franchise list of all-time leaders in penalty minutes, McSorley’s 1,846 will likely never be touched (as No. 2, mild-mannered Dave Taylor, is nearly 250 minutes behind him.) McSorley’s 3,381 penalty minutes are fourth all-time in NHL history.

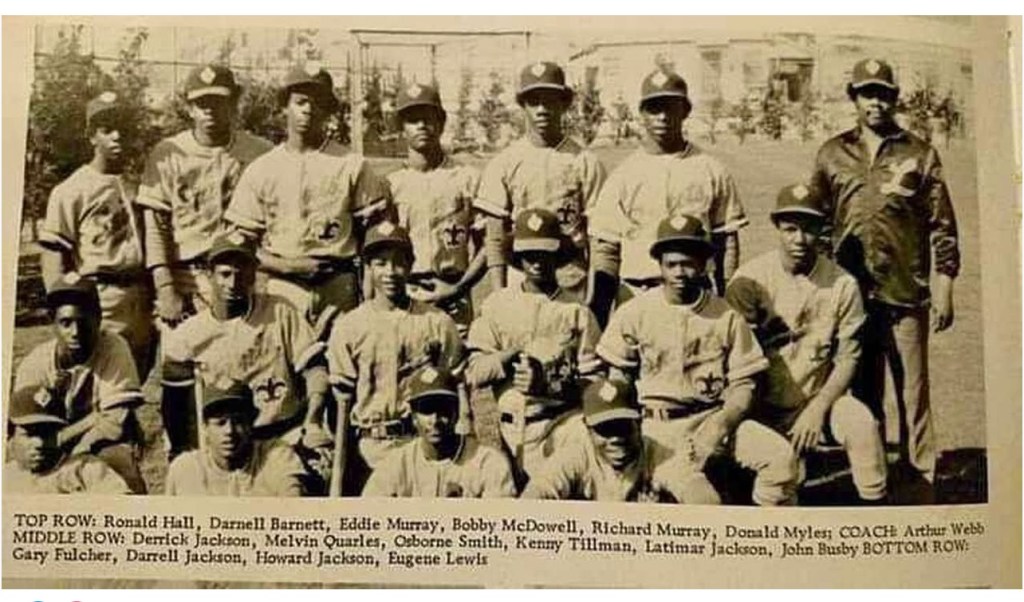

Eddie Murray, Los Angeles Dodgers first baseman (1989 to 1991, and 1997), Anaheim Angels first baseman (1997):

The eighth of 12 kids in his family, Eddie Murray noted in his Baseball Hall of Fame speech to thank Little League coach Clifford Prelow, a one-time Brooklyn Dodgers minor leaguer, for putting him on the path to success. After shining at L.A.’s inner-city Locke High, wearing No. 30 and a teammate of Ozzie Smith, Murray was a third-round pick by Baltimore and established himself as the 1977 AL Rookie of the Year, a seven-time AL All Star and winner of three Gold Gloves and two Silver Sluggers. After the Dodgers’ 1988 World Series run, they brought the 33-year-old Murray back home in exchange for three prospects. Murray gave them some star power the next three seasons as a 1991 NL All-Star. In ’90, he was second in the NL batting race with a .330 average and fifth in NL MVP voting. His departure as a free agent after three seasons opened first base up for rookie Eric Karros. The Angels scooped up Murray in 1997 at age 41 (after he returned to Baltimore for what looked like a farewell season and his 500th career homer) and he hit the last three of his 504 homers. The Dodgers picked him up to end that ’97 season (nine games, seven at bats). A 68.6 WAR, he remains one of the greatest switch hitters of all time, second all-time with 3,255 hits and the most RBIs with 1,917. He is one of only four players in MLB history to log 500 homers and collect 3,000 hits. Read more at EddieMurray33.com.

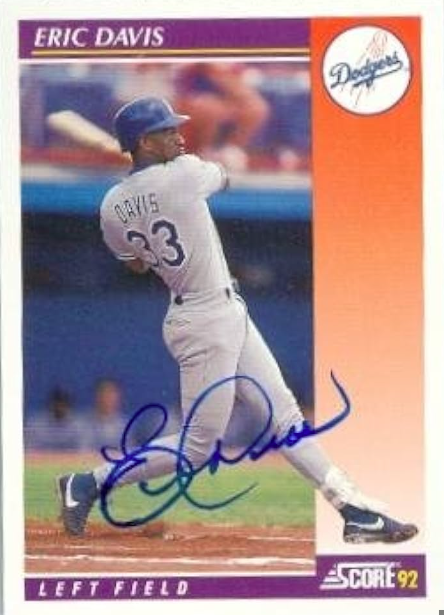

Eric Davis, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (1992 to 1993):

His L.A. roots went back to the basketball courts of Baldwin Hills Rec Center, aspiring to play in the NBA. It took him to Freemont High in South L.A., where he averaged 29 points and 10 assists a game as a senior. But on the baseball diamond, he was even better: He hit .635 and stole 50 bases in 15 games. Davis had no interest in going to college, so the path to the NBA was limited — and he accepted the Cincinnati Reds’ offer to join as their eight-round pick in the MLB Draft (the same one where his friend, Darryl Strawberry, went No. 1 overall from Crenshaw High). One of the game’s most talented power-and-speed players for nine seasons in Cincinnati, Davis went back to L.A. when the Dodgers exchanged him for pitchers Tim Belcher and John Wetteland. Injuries had caught up with Davis, and he managed to play in a handful of games, briefly sharing the outfield with Strawberry. Before the ’94 season ended, the Dodgers sent Davis to Detroit.

Seth Etherton, USC baseball pitcher (1995 to 1998): A three-time All-American and two-time conference Pitcher of the Year out of Dana Hills High, Etherton became the National Player of the Year when he struck out 182 in 1998 to just 29 walks, leading USC to a College World Series title. His 420 career strikeouts rank second in USC history and his 37 career wins rank fifth. He eventually wore No. 35 for the Anaheim Angels in his MLB debut season of 2000 (5-1 with a 5.52 ERA in 11 starts) after the team made him a first-round draft choice in 1998.

Have you heard this story:

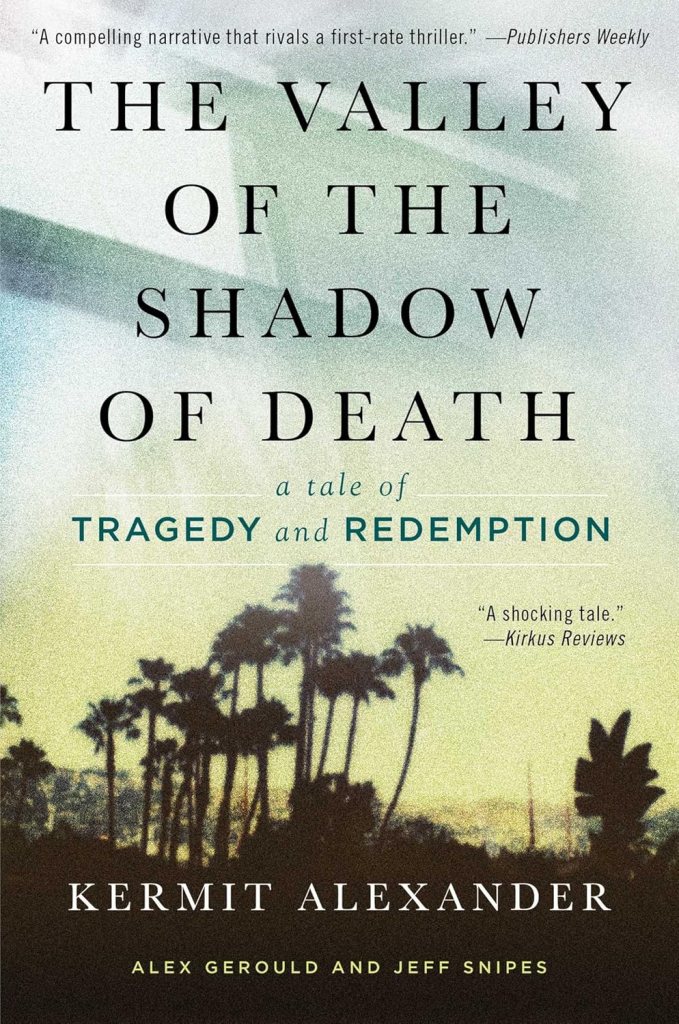

Kermit Alexander, UCLA football running back/defensive back (1960 to 1962):

USC football coach John McKay called Alexander the best college player in the country when he saw him in the 1963 East-West All Star game prior to the upcoming NFL draft. At UCLA, Alexander not only was the NCAA Track and Field champion in the triple jump in 1962, but he was a world-class 100-yard sprinter. He was inducted into the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 1986.

Out of Los Angeles’ Mount Carmel High — and a teammate of the McKeever brothers — Alexander’s three seasons at UCLA saw him run for 660 yards on 118 carries and six TDs, plus catch 29 passes for 482 yards and two TDs. He also returned punts and kickoffs.

One of the perhaps overlook aspects of Alexander’s time at UCLA was when he led a group of eight Black Bruins players in threatening to boycott the 1962 Rose Bowl had Alabama’s Bear Bryant been successful in lobbying for his team to get a backdoor invitation to face the Bruins instead of the usual Big Ten representative. Ohio State won a share of the conference title with Minnesota, but the Ohio State Senate Faculty voted to decline the Rose Bowl bid, fearing head coach Woody Hayes, who won the national title in 1954 and ’57, had turned the school’s reputation into a “football factory.” Bryant saw that as a way to get an invitation for his team, but Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray wrote two scathing columns about the South’s deifying Bryant and the Jim Crow society supporting the Crimson Tide program. “If we can’t play on their field in Alabama, why should they be able to play on our field in Pasadena?” Alexander told writer Tom Shanahan in a 2015 interview recalling the player protest. UCLA’s 1961 response was fueled by the progress of the Civil Rights movement.

Alexander was the fifth-overall draft pick by Denver in the 1963 AFL draft, but he picked the NFL and San Francisco (No. 8 overall) and made his only Pro Bowl selection in 1968 — the same year he put on a hit on Chicago’s Gayle Sayers that seriously damaged his knee and his career. Traded by the 49ers to the Rams in 1970 for placekicker Bruce Gossett, Alexander started every game as a right corner and strong safety, making seven interceptions in two seasons, return two for touchdowns. With the Rams, he was also voted the 1970 NFL NFLPA Alan Page Community Service Award winner as he was the Rams’ representative in the players union, where he served as president in 1975.

Later a sportscaster at KABC-Channel 7, Alexander details in his autobiography, “The Valley of the Shadow of Death: A Tale of Tragedy and Redemption” how he endured through the 1984 murder of his mothers, sister and two nephews in South Central L.A. during a home invasion by a neighbor gang — a mistaken identity crime.

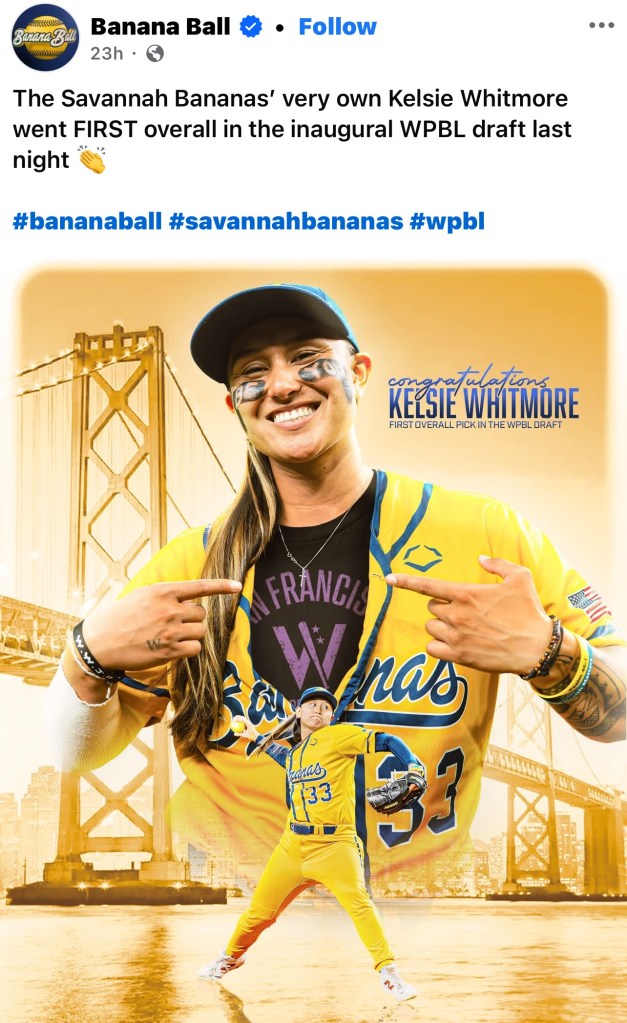

Kelsie Whitmore, Cal State Fullerton softball outfielder (2017 to 2021):

When Kelsie Whitmore spent the 2022 and 2023 seasons pitching for the Staten Island (N.Y.) FerryHawks of the independent Atlantic League, she became the first woman to play professional baseball that high up the baseball ladder (considered Triple-A) in more than 70 years. She did it with a pitch she called “The Thing” — an offshoot of the knuckleball Whitmore discovered while “messing around with some other pitches” and something pitching coach Nelson Figueroa, a former MLB player and FerryHawks pitching coach, could help her develop.

When Whitmore, at age 17, right off the boy’s baseball team at Temecula Valley High, made her debut in men’s pro baseball in 2016 with the Sonoma Stompers of the independent Pacific Association, along with teammate Stacy Pigno, the National Baseball Hall of Fame said it was the first time there were female teammates in professional baseball since the 1950s, when women played in the Negro Leagues.

Now, as the Women’s Pro Baseball League held its inaugural 2025 draft for a four-team league slated to launch in the summer of ’26, the 5-foot-6, 130-pound Whitmore, at age 27 and listed as a relief pitcher/right fielder/center fielder, had another first — she was selected first overall.

Whitmore is familiar with being the only female player on her baseball team since Little League when she was 6, but her goal was to play pro baseball. Playing in the WPBL will bring her validation she said. “It made me just feel like it was all worth it in the end,” she told the New York Times. “Like all the late nights, all, you know, whatever, tears, struggles, stress, conversations with my family … and trying to just find … opportunity,” she said. Whitmore had been a member of the U.S. women’s national baseball team since 2014, and in 2022, she was named USA Baseball Sportswoman of the Year. Over her five years playing for the national team, Whitmore compiled a 1.35 ERA as a pitcher and also played the outfield. This WPBL opportunity comes a year after she waited her time playing with the traveling Savannah Bananas baseball team.

In a 2022 essay for The Players Tribune, Whitmore admitted playing softball was OK, but not her end game. At Fullerton, Whitmore was the 2021 Big West Field Player of the Year as part of the Titans’ three consecutive Big West titles (2017–2019). As a senior, she hit .395 and finished a five-year carer hitting .300 with 19 homers and 64 RBIs in 227 games. But that was softball. The next year, she made her historic appearance in Staten Island as a pitcher, striking out six hitters in 22 2/3 innings. In ’24, she pitched 23 innings for the Pioneer League’s Oakland Ballers to be on the Forbed 30 Under 30 Sports list of people to watch. Her five seasons of minor-league baseball ages 17 and 18 before college and then ’22-’24 afterward, she was 0-3 with a 12.04 ERA in 49 1/3 innings over 39 games. With a degree in kinesiology and masters in instructional design and technology, Whitmore is still looking for more. Her dream is to sign an MLB contract with the San Diego Padres — the team she grew up watching. When will we see a female pitching in the big leagues? One of the first to get close was Ila Borders (see entry No. 22 in this series). While Borders went it alone, Whitmore is part of a movement.

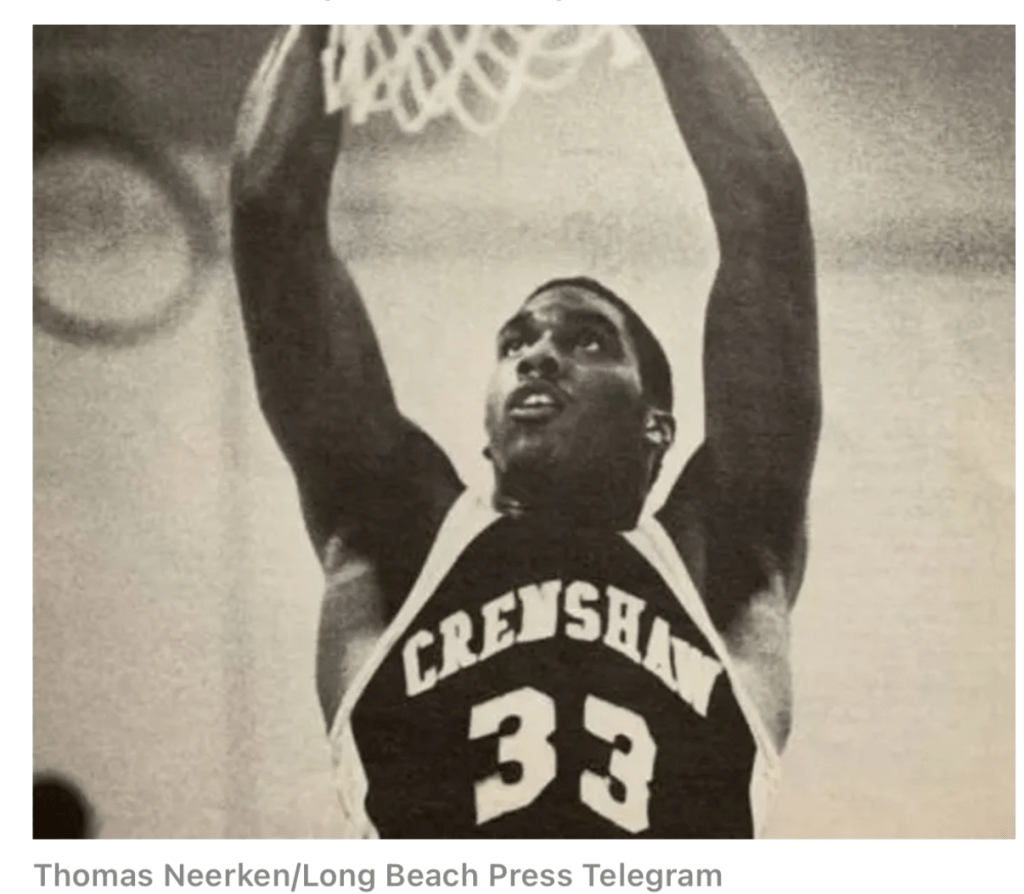

John “Hot Plate” Williams, Crenshaw High (1980 to 1984):

At 6-foot-8 and 230 pounds, Williams was a man among boys in dominating the high school scene as California’s Mr. Basketball as a junior and season, leading his team to the ’83 state title. He went onto two seasons at LSU and a first-round pick by the NBA’s Washington Wizards in 1988. After the Wizards suspended him for the entire 1991-92 season being overweight, the Los Angeles Clippers brought him on for two seasons (wearing No. 34 in 1992-93 and 1993-94). The nickname “Hot Plate,” a reflection of his habit of using food to deal with depression and stress that pushed him beyond 300 pounds, was a way to distinguish him from another NBA player at that time, John “Hot Rod” Williams, who had a 13-season NBA career from 1986 to 1999 parallel to him.

Karim Abdul-Jabbar, UCLA football running back (1993 to 1995):

Sharmon Shah came out of L.A. Dorsey High to set a Bruins’ school record for rushing yards in a season with 1,419 as a junior. The team MVP in ’94 and ’95, he left to the NFL before his senior season with a combined 3,030 yards and 36 touchdowns, among the most in UCLA record books. Where he literally really made a name for himself was in his conversion to Muslim in 1995. As Karim Abdul-Jabbar, and also wearing No. 33, it confused some as thinking he was the offspring of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, the former UCLA basketball star who actually had a son named Kareem. That led to a strange lawsuit — the basketball player suing the football player in 1997. As a result, the football player had to change his name legally to Abdul-Karim al-Jabbar.

Eli Grba, Los Angeles Angels pitcher (1961 to 1963):

When the New York Yankees made Grba expendable in the 1961 expansion draft, manager Casey Stengel advised the Angels to swoop him up — and they did, with the first pick, making him the first official Angel. With that came having Grba on the mound for their inaugral Opening Day start in Baltimore on April 11, 1961. He went the distance in a 7-2 win over the Orioles. “It really wasn’t until afterward that everyone starts making a big deal out of it,” Grba once told me. “Mr. Autry comes down to the locker room and there’s the newspaper guys and the whole thing. That’s when I guess I really understood what was happening.” Two weeks later, Grba pitched in the Los Angeles Angels’ first home game at L.A.’s Wrigley Field, a 4-2 loss to Minnesota. Only 11,931 came out for it. “Maybe it just took awhile for everyone to figure us out. Who’s this team? Who’s Eli Grba, that guy with the funny name?” He ended up a 20-24 career mark in three seasons for the Angels, including their first playing at Dodger Stadium, with a 4.40 ERA in 92 games. His 2016 biography, “Eli Grba: Baseball’s Fallen Angel,” which explained how he dealt with the demons of alcohol abuse, was published three years before he died in 2019 from cancer at age 84. In the 1973 book, “The Great American Baseball Card Flipping, Trading and Bubble Gum Book,” a ’61 Topps card of Grba includes the notation: “In addition to having the hardest name to pronounce in the big leagues he also had just about the worst stuff. … Eli was cut adrift (by the Yankees) in the first expansion draft to the Los Angeles Angels. Here he joined Ted Bowsfield, Ron Kline, Ryne Duren and Art Fowler to make up what must have been the most totally and unredeemedly washed up pitching staff of all time.”

Hot Rod Hundley, Los Angeles Lakers (1960-61 to 1962-63):

Consider the title of his 1970 autobiography (along with the photo): “Clown: Number 33 In Your Program, No. 1 In Your Heart.” That’s a reference to the digits that the two-time All-American from West Virginia wore for the Lakers, not only in the last three seasons they were in Minneapolis, but also their first three seasons in L.A. Rodney Hundley, by name, was the No. 1 overall pick in the 1957 NBA Draft by the Rochester Royals and traded to the Minneapolis Lakers with four others in exchange for star Clyde Lovellette. The Lakers’ hot-shot starting point guard was on teams that went to the Finals in ’62 and ’63 and lost to Boston. After his six seasons were cut short by bad knees, he moved into the broadcasting realm and was Chick Hearn’s first real partner on the Lakers’ radio. Hundley ended up in the media wing of the Basketball Hall of Fame for the 35-seasons he put in with the New Orleans/Utah Jazz. Between Hundley’s departure from the Lakers and Kareem-Abdul-Jabbar’s arrival, six other players wore No. 33. Including:

Cazzie Russell, Los Angeles Lakers forward (1974-75 to 1976-77):

His free-agent signing with the Lakers before the 1974 season meant the team had to give Golden State their 1976 first-round draft pick. It turned out to be center Robert Parish. With the Lakers, Russell was given No. 33, which he had once work with the New York Knicks, but when Kareem Abdul-Jabbar arrived for the 1975-76 season, Russell gave him the number and took No. 32. Russell has now become a trivia answer: Who was the last Laker to wear No. 33 before Abdul-Jabbar, and the last to wear No. 32 before Magic Johnson.

Lisa Leslie, Morningside High basketball (1986 to 1990); USC basketball (1990 to 1994):

Before she sported No. 9 for the WNBA’s Los Angeles Sparks, Leslie wore No. 33 for her four years of high school and college. Was her affinity for Kareem Abdul-Jabbar? In our post explaining why we’ve assigned her the player for No. 9, we covered her 101 point game at Morningside in 1990 and her four-time All-Conference career at USC that landed her the Naismith Award — and having No. 33 retired both by Morningside High and USC. In her 120-game college career, she averaged 20.1 points and set Pac-10 conference records for 2,414 points, 1,214 rebounds and 321 blocked shots.

Terrell Davis, Long Beach State football tailback (1990 to 1991):

The Pro Football Hall of Famer who won two Super Bowls, an NFL MVP Award and had a 2,000-yard rushing season wearing No. 30 was asked once if he could go back to any year of his career, what would it be? “For me it’s always 1990, my freshman year at Long Beach State,” Davis said. “That was the best time of my life.” Davis sat out his first year and played five games his second season, rushing for 262 yards and two touchdowns, plus another receiving TD and 92 total yards. He was recruited out of San Diego Lincoln High to play at Long Beach State by coach George Allen, whose death on New Year’s Eve 1990 put the program in jeopardy. Former USC and NFL running back Willie Brown was recruited to be the head coach for what would be the program’s final year was the team finished 2-9. “He called me Secretariat,” Davis said of Allen, who compared him to the famous thoroughbred. “So, if I’m getting the stamp of approval from this coach, I have to be pretty good. I’m special. Something is going on here. If he names me Secretariat and he’s pretty high on you … that felt good.”

Aaron Bates, Lancaster JetHawks first baseman/outfielder (2007): A sixth-round draft pick by the Boston Red Sox, Bates was sent to the team’s Single-A affiliate in Lancaster and he announced his arrival somewhat quickly. On May 19 against Lake Elsinore, Bates was the first player in the 66-year history of the California League to produce a four-homer game (plus a single to make it a 5-for-5 day). Perhaps more strange: His teammate, Brad Correll, had a four-homer game for the JetHawks against the High Desert Mavericks a month later. Bates put together a season hitting .332 with 24 homer and 88 RBIs in 99 games for the JetHawks. He would only get 11 at bats in 2009 for the Red Sox as his MLB career stats. The Dodgers picked him up in 2014 and he went to Double-A Chattanooga, but for only 11 games. He ended up as a coach with the Dodgers’ Arizona League teams in 2015 and ’16, and the Dodgers made him an assistant hitting coach in 2019, then co-hitting coach in 2023. He still goes by the Twitter account of @A33bates.

We also have:

Ziggy Palffy, Los Angeles Kings right wing (1999-2000 to 2003-04)

Tommy Hawkins, Los Angeles Lakers forward (1966-67 to 1968-69): Also wore No. 20 for the franchise from 1959-60 to 1961-62)

Vic Davalillo, Los Angeles Dodgers pinch hitter (1977 to 1980)

Brian Jordan, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (2002 to 2003)

David Price, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2021 to 2022)

James Outmann, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (2023 to present): Also wore No. 77 in 2022

David Wells, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2007)

Luis Tiant, California Angels pitcher (1982)

Matt Harvey, Los Angeles Angels pitcher (2019)

Gary DiSarcina, California Angels infielder (1992 to 1996): Also wore No. 4 in 1989 and No. 11 from 1990-92.

C.J. Wilson, Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim pitcher (2012 to 2015)

Steve Bilko, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (1958)

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 33: Lew Alcindor / Kareem Abdul-Jabbar”