This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 52:

= Keith Wilkes: UCLA basketball

= Jamaal Wilkes: Los Angeles Lakers/Clippers

= Marv Goux: USC football

= Jack Del Rio: USC football

= Khalil Mack: Los Angeles Chargers

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 52:

= Happy Hairston: Los Angeles Lakers

= Burr Baldwin: Los Angeles Dons

= Eddie Piatkowski: Los Anglees Clippers

The most interesting story for No. 52:

Keith Wilkes: UCLA basketball forward (1971-72 to 1973-74)

Jamaal Wilkes: Los Angeles Lakers forward (1977-78 to 1984-85); Los Angeles Clippers forward (1985-86)

Southern California map pinpoints:

= Santa Barbara; Westwood (UCLA); Inglewood (Forum)

Before he was Jamaal, he was Keith. And before that, Jackie.

Before he was smooth as “Silk,” he was a little corny as “Cornbread.”

Two weeks before Keith Wilkes’ UCLA No. 52 was retired at Pauley Pavilion in January 2013, Jamaal Wilkes’ Lakers’ No. 52 was put up on the wall at Crypto.com Arena in December of 2012. Somehow, the No. 52 he wore for the Clippers in the waning days before his retirement from the NBA isn’t worthy of retirement also.

It was 18 years before he was inducted into Springfield’s Basketball Hall of Fame in 2012 that he was already in Westwood’s UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame.

Most all of it, the deadly results of aside-winding shot that looked as if he was flyfishing made Lakers broadcaster Chick Hearn used to call it another “20-foot layup.”

The story

Jackson Keith Wilkes — who disliked the nickname Jackie that his family was calling him and wanted to go by his middle name — moved to Ventura in the second grade and lived there nearly 10 years, playing at an All-CIF level for two seasons at Ventura High as a sophomore and junior. He was named student body president at Ventura for his senior season, but when his father, Baptist pastor L. Leander Wilkes, took a new position in Santa Barbara, his family followed and the son landed at Santa Barbara High, with future Lakers teammate Don Ford. The team had a 26-game win streak and made the CIF semifinals.

That’s when Wilkes became a prized recruit of UCLA coach John Wooden.

“I would have the player be a good student, polite, courteous, a good team player, a good defensive player and rebounder, a good inside player and outside shooter — why not just take Jamaal Wilkes and let it go at that,” Wooden once said when asked to describe his ideal player.

Wilkes, who would earn Academic All-American honors three straight seasons, had the fortune of joining a UCLA program in the same freshman class as Bill Walton. Two SoCal guys who would add more local flavor and become one of the most dominant teams of college basketball history.

Prior to the Wilkes-Walton infusion — the two were among the freshman not allowed to play varsity in those days — the Bruins’ 1970-71 team went 29-1 and won its fifth straight national title. Its only loss was 89-82 at Notre Dame on Jan. 23, ’71. The won their final 15 games of that season.

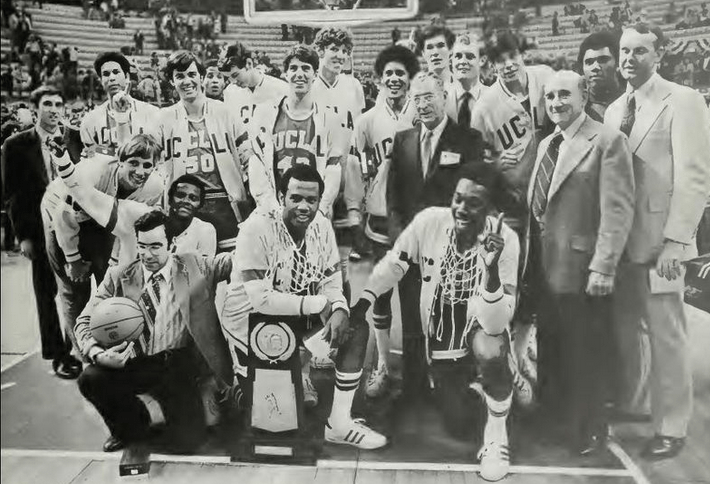

When the ’71-72 season started, 6-foot-6 sophomore forward Wilkes (13.5 points a game, 8.2 rebounds) joined the front court with 6-foot-11 center Walton (21 points, 15 rebounds). With senior guard Henry Bibby, they ran off a 30-0 season and another NCAA title against Florida State, 81-76, at the L.A. Sports Arena. Wilkes’ 20 points and 10 rebounds complimented Walton’s 24 and 20 rebounds, as both survived the end of the game with four fouls. That gave the program 45 wins in a row.

The ’72-’73 team cranked out another 30-0 mark, a seventh title in a row, and the winning streak was up to 75 after junior Wilkes averaged 14.8 points and 7.3 rebounds a game, second only to junior teammate Walton’s 20.4 points, 16.9 rebounds. In the 87-66 win over Memphis State in St. Louis, Wilkes’ 16 points made him the only other Bruin in double figures behind Walton’s dominant 44 points and 13 rebounds.

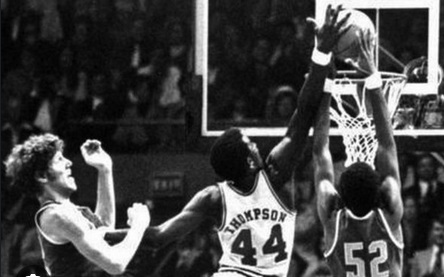

The 1973-’74 team saw Wilkes average 16.7 points, 6.6 rebounds and 2.2 assists. The UCLA winning streak was halted at 88 after a loss at Notre Dame, on Jan. 23, ’74. Same date at the last loss. So three years in a row of never losing. The national title streak was also broken when North Carolina State outlasted the Bruins 80-77 in double overtime in the national semifinals in Greensboro, N.C. Wilkes played 49 minutes but was held to 15 points by NC State’s David Thompson and fouled out.

One of the images left from that game is of Thompson blocking a shot of Wilkes’ as Walton is pushed away.

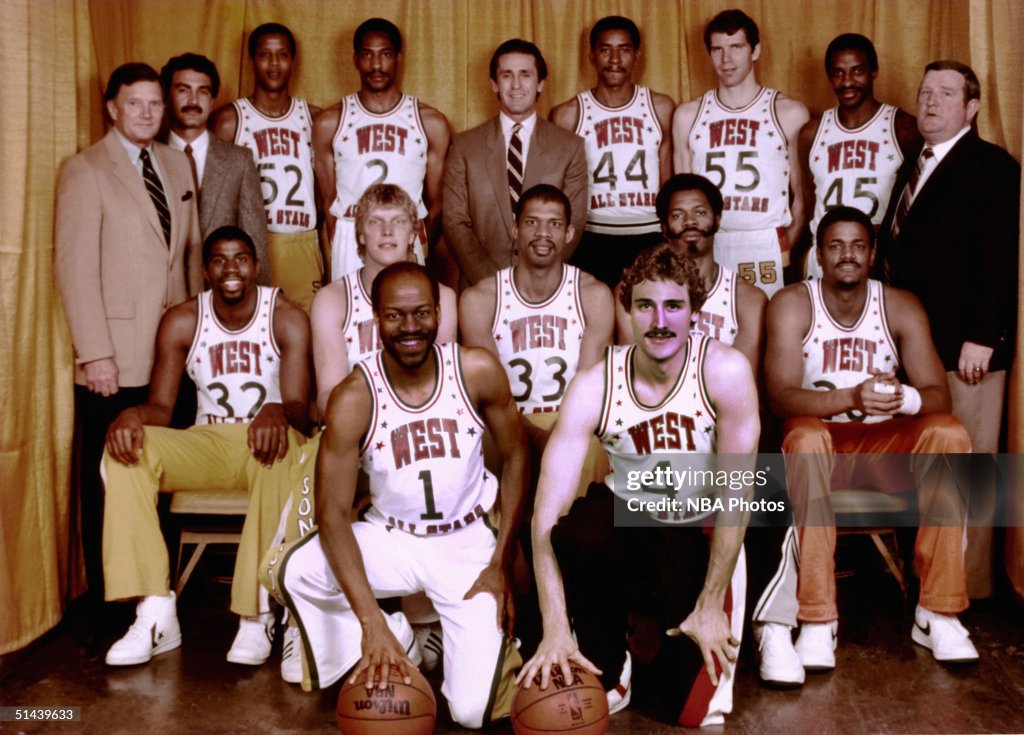

Two months later, in the ’74 NBA draft, Wilkes went No. 11 overall to Golden State (as Walton went No. 1 overall to Portland). Wilkes joined a roster (wearing No. 41, since backup center George Johnson had No. 52) with Rick Barry and became the team’s second-best scorer at 14.2 points a game with 8.2 rebounds, winning the NBA’s Rookie of the Year honor and helping both with needed offense and defense against Washington’s Elvin Hayes as the Warriors clinched the NBA title. A year later, Wilkes would make the NBA All-Star team (averaging 17.8 points and 8.8 rebounds) and by his third season, he already was twice on the NBA All-Defense second team.

By then, he converted to Islam. He officially changed his name to Jamaal Abdul-Lateef, but used his birth surname Wilkes on the back of his jersey. It was at a time when two other prominent UCLA basketball players in the NBA were also overt about their religious convictions — In 1971, Lew Alcindor changed his name to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar; in ’72, Walt Hazzard changed to Mahdi Abdul-Rahman.

The Lakers, coming off a loss in the 1976 Western Conference finals, decided they had a need for someone like Wilkes.

When Wilkes signed to return to L.A. as a free agent, and all it cost the Lakers was a 1978 first-round draft pick (which turned out to be Purvis Short). Wilkes’ arrival to a team coached by Jerry West was focused on Kareem Abdul-Jabbar at center and needed some outside shooting presence.

When Magic Johnson arrived for ’79-’80, Wilkes finally topped a 20-points a game scoring average. His most noteworthy achievement was in the decisive 123-107 Game 6 win during the 1980 NBA Finals against Philadelphia. In a contest best remembered for the rookie Johnson jumping center for the injured Abdul-Jabbar and playing all five positions, scoring 42 points with 15 rebounds and seven assists, Wilkes actually made more shots (16 to Johnson’s 14) that lead to 37 points and 10 rebounds. Wilkes scored 16 of his 37 in the third period, and was the game’s leading scorer until Johnson surpassed him with a couple of made free-throws after the game was iced and the Sixers resorted to late-game fouling.

Was he the series “forgotten hero?”

For four seasons — 1979-’80 to 1983-’84 — Wilkes averaged 20.8 points per game and 5.2 rebounds for the Lakers, helping them win another championship in 1983. He would eventually lose his starting forward spot to James Worthy in the ’84-85 season, missing games with an assortment of injuries including a strange virus and tearing ligaments in his left knee.

Worthy sized Wilkes up this way: “He had the John Wooden science and theory about the game down. You never saw him play that much above the rim. He had speed, but … it was about putting yourself in the right position (on the fast break). I learned a lot from him.”

The Lakers waived Wilkes prior to the 1985-86 season, and the Clippers took him in, a season after Walton left. The Clippers gave him No. 52, yet he retired from the team just three months later at age 32, worn out.

Wilkes’ collective achievements at UCLA, Golden State and with the Lakers was deemed enough for the Basketball Hall of Fame recognition in 2012, after an NBA career that saw him score 14,664 points (17.7 a game) and have 5,117 rebounds (6.2 a game), plus All Star appearances as a Laker in ’81 and ’83.

When Wilkes was inducted into the Hall, Lakers owner Jerry Buss said: “Anyone who truly knows and loves the game of basketball surely recognizes what a special and gifted player Jamaal Wilkes was. A rare combination of selflessness and grace, Jamaal made the game look effortless.”

The shot

Can anyone explain the logistics behind how Wilkes launched the basketball?

“It came from the playgrounds,” he once said. “When I was 11-12, I was a pretty good basketball player in Ventura and I began playing with older guys. I was going from the nine-foot to the 10-foot hoops, and of course they wanted to play on the 10-foot hoops, and they would block my shot every single time. So, I just learned to hold it back there until the last minute and I never realized I was doing anything different until I got to UCLA. Even then, I wasn’t sure I was doing anything different.”

Wilkes said at one point Wooden called him over one day after practice early in his sophomore season.

“He said, ‘Come here, Keith. Let me see how you shoot that ball. I want you to shoot some shots around key.’ I was really confused by that — and also terrified because you didn’t want the man calling you out about anything, especially around the other guys. So, I did what he said and he said he would rebound for me.

“Well, that really confused me. I thought he was going to call one of the other players to rebound for me. What I remember about that, every pass was just perfect. I said (to myself), I could get used to playing with this guy. And I was drilling it, because you know, my manhood, my credibility, everything was on the line I felt at that moment.

“So he called me back and said, ‘OK, how did you shoot that again?’ And I was like, ‘You just saw me shoot 40-to-50 shots, right?’ So I said, ‘OK, I go like this (Wilkes pulled his arms behind his head), I go like that (Wilkes moved his arms in a shooting motion).’

“Then he said, ‘Well, does it leave your finger tips with (backspin)?’ And I thought about it and I said, ‘Well, yeah, coach.’ And he said, ‘OK, you’re dismissed.’

“Years later we laughed about it. He said he thought about changing it but my setup and my finish, he thought, was textbook. Whatever happened in between he decided to leave it alone, and I’m so glad he did.”

The movie role

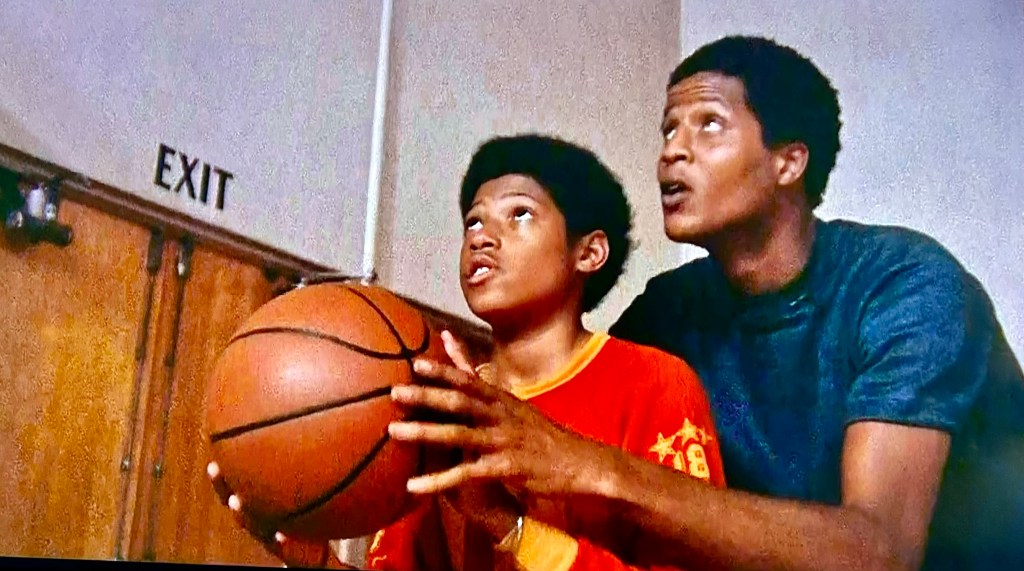

Not really spoiler alert here: About 30 minutes into the 1975 African-American culturally relevant film “Cornbread, Earl and Me,” Keith Wilkes dies.

At least it’s only the character he plays named Nathaniel “Cornbread” Hamilton.

Wilkes was 22 years old, a year into his NBA playing career, when he was recruited for the role in a coming-of-age drama as an 18-year-old Chicago high school basketball star about to be the first in the neighborhood to go to college. His screen time isn’t a whole lot: He is shot by police chasing another burglary suspect, and the shooting is witnessed by two young boys, Earl and Wilford.

Wilkes said he knew about the script a couple years earlier as a senior at UCLA when producer Leonard Lamesdorf showed it to Wooden.

“Coach Wooden called me into his office, gave me the script and said, ‘Read it and think about playing the part’,” Wilkes told the Camden (New Jersey) Courier-Post. “I read every line of it in a single night. I was excited. I agreed to do it.”

This would be a film that resonated in the African-American community, dealing with with police force in the inner city and a community afraid to speak up. African-American stars such as Moses Gunn, Rosalind Cash and Bernie Casey held together the cast and kept it authentic. The real surprise was introducing 14-year-old Laurence Fishburne (as Wilford Robinson) in his first feature film, and giving him the most compelling scene as he is in court testifying about what he witnessed.

“Cornbread, Earl and Me” has been compared to Spike Lee’s “Do The Right Thing” in 1989 and John Singleton’s “Boyz In the Hood” from 1991. This also showed how an NBA athlete could do Hollywood in a serious manner, before Ray Allen was in “He Got Game” in 1998.

As “Cornbread,” Wilkes said he only needed two and a half weeks of shooting in L.A. to finish his part.

“I was nervous the entire time,” he said. “I studied hard enough to get through the difficult scenes. But the easy ones were much harder.”

One scene with Fishburne is Wilkes showing him how to shoot.

“Put it on your fingertips, hold it high and let it fly,” Cornbread tells Wilford as they are practicing at the school gym.

A couple of local hoodlums interrupted and confronted Cornbread about throwing away drugs that had been stashed in the locker room. Cornbread ended up showing his ability to fend off a knife attack with the help of his basketball.

“I had to go through several readings — they felt the film had so much basketball (action) it would be easier to convert an athlete into an actor rather than an actor into an athlete,” Wilkes once said.

Producer and director Joseph Manduke framed the story around the 1966 book by Ronald Fair, “Hog Butcher,” who also wrote the screenplay.

How to measure the movie’s cultural impact? Cedric Maxwell, a standout at UNC Charlotte in ’75 before he became a two-time NBA champion with the Boston Celtics (and had his No. 31 retired), ended up having to wear the nickname “Cornbread” after he and his college teammate Melvin Williams went to see it. Watkins said he thought Maxwell looked like Wilkes. Although Maxwell didn’t like the nickname, the New York media picked up on it and that’s how Maxwell was referred to when he was named MVP of the National Invitational Tournament in 1976.

For what it’s worth, in the 1985-’86 season, Wilkes and Maxwell were teammates for a time on the Clippers.

When “Cornbread, Earl and Me” aired on Turner Classic Movies channel, Dr. Lonnie G. Bunch III, the secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, noted that in 1975 there were blaxploitation films such as “Shaft” (1971), “Superfly” (1972) and “Foxy Brown” (1974) that were popular as cultural markers in the urban community.

But “Cornbread, Earl and Me” was more like films such as “Claudine” (1974), “Sounder” (1972) and “Cooley High” (1975).

“One of the most powerful things about this film is watching Cornbread with his mother and father, and a sense of family was captured very well,” said Bunch. “For me, it’s a film about hope and about hard work. You see (Cornbread) practicing every day. He has pressure, but he also has joy of playing basketball. Then the reality of life in a city changes everything.

“Regardless of the cause (of the shooting) you see the loss and someone who help could help transform a society not have that chance, because he happens to be Black and in the wrong place.”

A New York Times review at the time included “It’s not every day that we get films that persist in extolling truth and decency even while making a bloody display of the unfairness of life. And judging by the warm-weather fare of the recent past, it isn’t likely that this spring and summer will offer too many films that — like ‘Cornbread’—can appeal to youngsters on a wholesome ethical plane while telling a story that bears some resemblance to life, and death, on real city streets … Making his movie debut … Wilkes (is) a pleasant personality but unlikely to win as an actor the accolade that he has just won for his feats with the Golden State Warriors.”

A TV Guide review: “(Wilkes) plays the lead with charm and conviction, and the picture goes to great lengths to portray the sensitive situation in complex terms.”

Hip Hop scholar Junious L. Brickhouse, in an essay for The American Folklore Society, wrote: “I can fully appreciate that being made to watch (it) was my mom’s best effort to start the conversations that would help us to understand that we were Black children, up against the same racist systems our parents wanted to dismantle, and would teach us a lesson in how to survive the construct and the agents of that system. It worked, and I am grateful. … I still watch ‘Cornbread, Earl and Me’ from time to time and am often reminded by a young Laurence Fishburne that doing the right thing takes more than a conscience; it takes courage.”

Who else wore No. 52 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

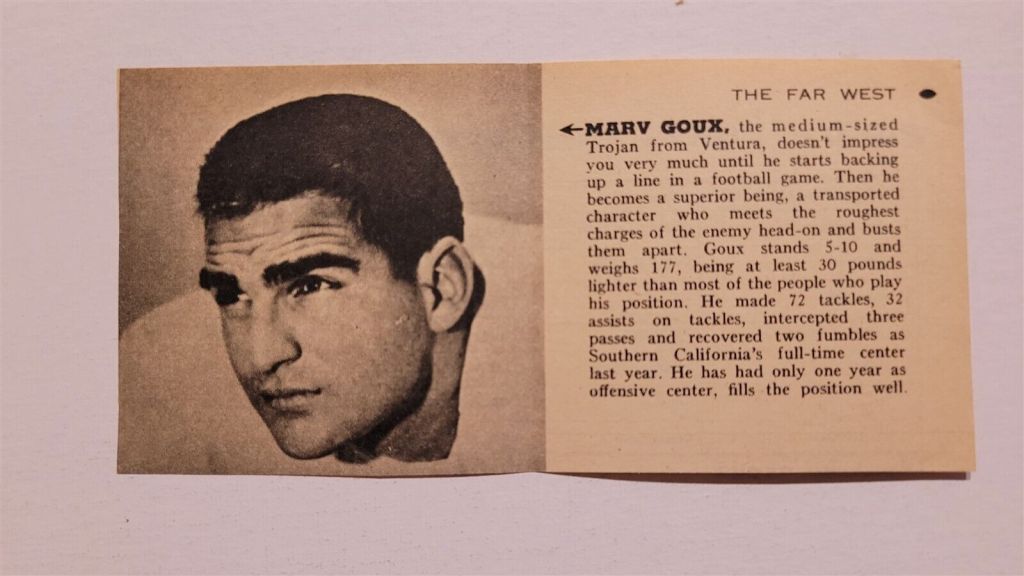

Marv Goux, USC football center/linebacker (1952 to 1955):

Best known: A three-year starter who used ’53 as a red-shirt season because of injury became the 1955 team captain and received the Davis-Teschke Award twice for most inspirational player. A JC All-American at Ventura Junior College in ’51, following his high school days at Santa Barbara High, Goux arrived at USC to play in two Rose Bowls. He grew into the title of “Mr. Trojan” mostly for all the time he spent as a defensive line coach, starting in 1957 when he (and Al Davis) joined the Trojan staff and was with head coaches John McKay and John Robinson during their dominant runs from 1966 to ’79.

During Goux’s coaching time at USC, the team won five national championships and eight Rose Bowls. He coached 11 first-team All-Americans.

As Sports Illustrated’s John Underwood once wrote about him in 1967: Marvin Goux has vicious black eves and over each one a heavy strip of macadam that looks like an eyebrow. He wears his hair cut short, in the style popular at state prisons, and he keeps his belly taut and flat for the Hollywood bit parts he plays by wearing rubber corsets that make him sweat when he is on the field at the University of Southern California, where he works as an assistant coach for John McKay. Marv’s manly figure has been seen on the screen whipping Tony Curtis into submission with a felt bullwhip, and on other less attractive adventures. Marv has a good scowl, a commendable frown. He comes across like trouble ahead. He is known as a fellow who rises to the occasion.

Goux left USC under the darkness of an NCAA ticket-selling scandal in 1982 and eventually joined Robinson as a defensive line coach with the Los Angeles Rams from 1983 to ’91. Goux was inducted into the first USC Athletic Hall of Fame class of 1994 and into the Rose Bowl Hall of Fame in 2000 having been involved as a coach or player in 13 games. Goux’s Gate is what they now call the entrance to the USC practice field, and the Marv Goux Award is given to the Trojan player of the game against UCLA. He died in 2002 at age 69.

Not well remembered:

Happy Hairston, Los Angeles Lakers forward (1969-70 to 1974-75):

Best known: On the Lakers’ 1971-72 title team that ran off a 33-game win streak, fans were pretty happy that Harold Hairston, who came over in a deal with Detroit for the ’69-’70 season, was in the starting lineup with Wilt Chamberlain, Jerry West, Gail Goodrich and Jim McMillian. Six of Hairston’s 10 NBA seasons were in L.A., through his retirement at 32 when the team waived him prior to the 1975-76 season. Hairston had a 29-rebond night for the Lakers in December of ’73 (to go with 20 points) and also had multiple 20-rebounds or more nights for the Lakers. A career-high of nine assists also happened in December of ’73. Two seasons after the Lakers released him, Wilkes came in to fill No. 52.

Not well remembered: During the “jump the shark” period of the “Happy Days” run on ABC, Hairston appeared in a 1981 episode called “Tall Story” as “Mr. Barrett,” the father of a player for the Jefferson High basketball team. Get it? Happy Hairston, “Happy Days.”

Jack Del Rio, USC football linebacker (1983 to 1984):

Best known: Recognized as a consensus All-American while putting up 96 tackles, 13 tackles for loss, a team-best seven sacks and seven deflections, Del Rio capped his Trojan career with a Rose Bowl MVP Award in the 1985 victory over Ohio State. Inducted into the USC Athletics Hall of Fame in 2015, Del Rio also played baseball at USC and was a 22nd round draft pick by the Toronto Blue Jays as a first baseman in 1981. A third-round draft pick by the New Orleans Saints in ’85, Del Rio’s NFL career lasted 11 years (one All-Pro season for Minnesota in ’94, wearing No. 55), before he became an NFL coach at Jacksonville (2003 to 2011) and with the Oakland Raiders (2015 to 2017).

Not well remembered: Del Rio was set up to appear on the Bob Hope Christmas Special in 1984 and laugh along with the comedian, who at that time was 81 years old at the time. “Yes, sir, when Jack is finished sacking quarterbacks, he can’t wait to turn pro so he can appear in beer commercials. He tells me he’s not sure which he enjoys more, a blitz or a Schlitz.”

Khalil Mack, Los Angeles Chargers linebacker (2022 to present):

Best known: In Week 4 of the 2023 season, Mack set a franchise record with six sacks (one short of the NFL mark) during a 24-17 home win over the Oakland Raiders, the sixth player to have at least six sacks in a game since sacks became an official statistic in 1982. A member of the NFL’s 2010s All-Decade Team for his play with Oakland and Chicago, Mack recorded his 100th career sack as a Charger in Week 17 of ’23.

Burr Baldwin, Los Angeles Dons left end (1947 to 1949): The first UCLA consensus All American (wearing No. 38, which the school retired) played from 1940 to ’42, served in World War II, and returned in ’46. His three years as a professional ended when he returned to serve with the Army in the Korean War (1951 to 53).

Erik Piatkowski, Los Angeles Clippers guard (1994-95 to 2003-04): “The Polish Rifle” was actually a No. 15 overall pick by Indiana but came to the Clippers in a trade after draft day, where he spent nine seasons and more than 600 games as a valued bench player and fan favorite.

Have you heard this story:

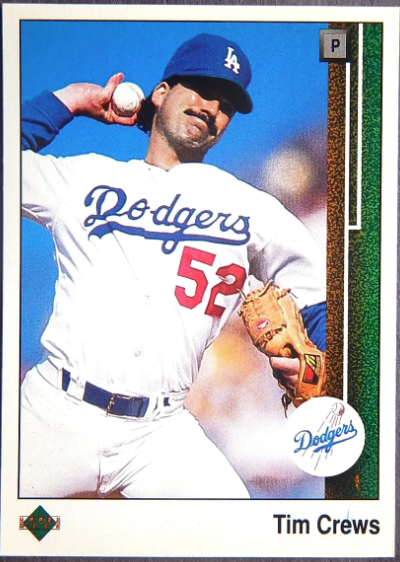

Tim Crews, Los Angeles Dodgers relief pitcher (1987 to 1992):

For the 1993 season, both the Dodgers and Cleveland Indians wore a black patch with the No. 52 on their sleeves. Crews’ entire six-year career as a player was with the Dodgers, highlighted by a 4-0 record and 3.14 ERA in during the 1988 championship run (thanks to many late comeback wins). The Dodgers actually obtained him (and starting pitcher Tim Leary) from Milwaukee prior to the ’87 season, shipping off Greg Brock. He became a free agent after the ’92 season, signed a deal with Cleveland in early ’93, but never played for the Indians. In March, during the Indians’ spring training, the 31-year-old Crews and fellow pitcher Steve Olin were killed in a boating accident on Crews’ property in Florida. Teammate Bob Ojeda also suffered serious head injuries.

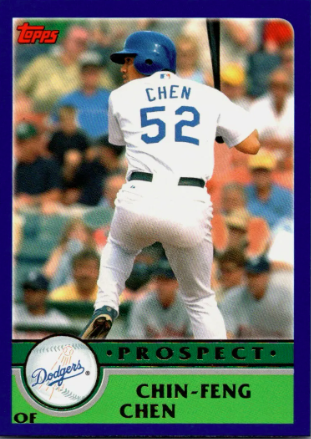

Chin-Feng Chen, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (2002 to 2005):

Dutifully noted that Chen became the first Taiwanese player in MLB history on Sept. 14, 2002. Even if his career spanned just 25 plate appearances in 19 games over four seasons, he did go 2-for-8 in 2005 – the first Taiwanese position player to get a hit in an MLB team, a two-run single — after starting out 0-for-14.

He did show plenty of signs in he Dodgers’ minor-league system of being worth investing their time. In 1999 while at Single-A San Bernardino, Chen became the first in the franchise’s minor league history to have 30 homers and 30 stolen bases in a season (.315, 31 HRs, 31 SB, 123 RBIs, 75 walks). When he eventually went back to the Chinese Professional Baseball League in 2016, his team, the Lamigo Monkeys, retired his No. 52. There was also pride in the country since Chen is one of the few who have played MLB after appearing in the Little League World Series, where in 1990, he was with San-Hua Little League from Chinese Taipei representing the Far East.

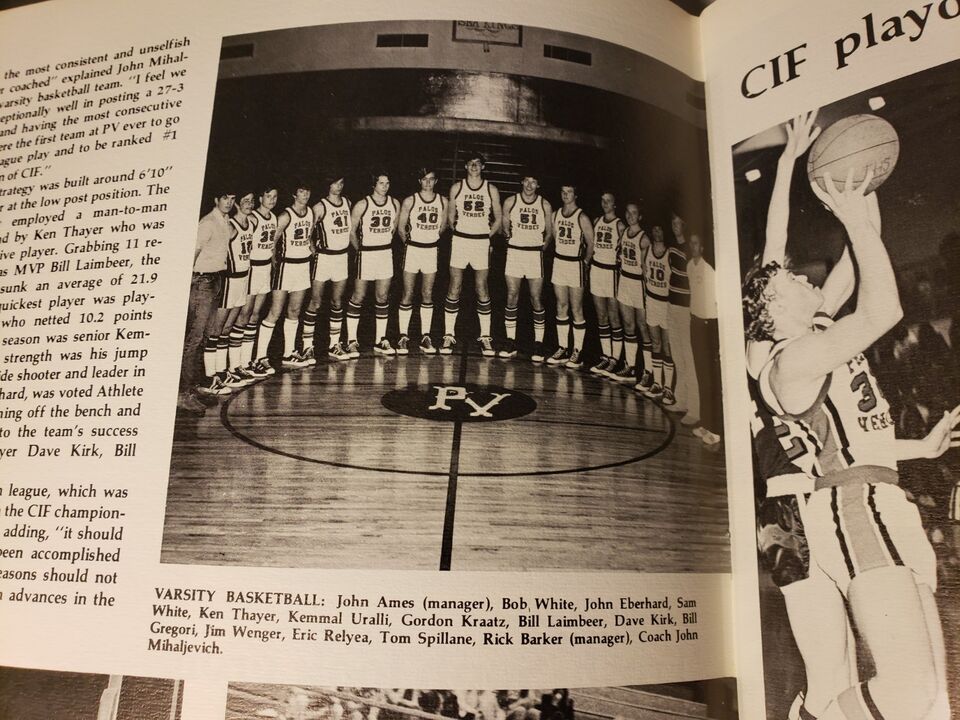

Bill Laimbeer, Palos Verdes High basketball center (1971 to 1975):

Before he was a four-time NBA All Star and two-time NBA champ as the nastiest of the Detroit Piston’s “Bad Boys,” Laimbeer was a Sleestack. The NBC kids TV show, “Land of the Lost,” needed large men to fill costumes. Laimbeer, at 6-foot-11, could accommodate. At the time, he was leading his team to a CIF title after an upset of six-time defending champion Verbum Dei. Laimbeer eventually went off to play at the University of Notre Dame for three seasons (flunking out after his freshman year) as a bruising rebounder (1975 to 1979) and was a third-round pick by Cleveland in ’79. He spent that year, however, playing overseas in Italy.

Traded to Detroit in ’81-’82, he was inserted as the starting center, began to appreciate the power of the scowl, and then drew his opponent out beyond the 3-point line where he enjoyed launching shots. Somehow, Laimbeer became the 19th player in league history to amass more than 10,000 points and 10,000 rebounds. He played all 82 games of the regular season five times, and never played fewer than 79 in his first 13 seasons. His streak of 685 consecutive games is fifth longest in league history and only ended because of a suspension. Laimbeer had his jersey No. 40 retired by the Pistons in 1995.

And here’s something you don’t see every day

We also have:

Tommy Lasorda, Los Angeles Dodgers third base coach (1973 to 1976). See his bio here for No. 2

Bill Madlock, Los Angeles Dodgers third baseman (1985): Also wore No. 12 in 1986-87.

Rod Martin, USC football linebacker (1975 to 1976)

Pedro Baez, Los Angeles Dodgers relief pitcher (2014 to 2020)

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 52: Keith Wilkes / Jamaal Wilkes”