This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 98:

= Tom Harmon: Los Angeles Rams halfback

The most interesting story for No. 98:

Parnelli Jones, race car driver (1949 to 1973)

Southern California map pinpoints:

San Pedro, Torrance, Palos Verdes Estates, Rolling Hills, Gardena (Ascot Park)

In the preface to his 2013 memoir, Parnelli Jones recalls a time where he didn’t really fight the law, and the law didn’t win either. But it made for a great story.

It was 1964 and, as he wrote, “my name had really gotten around. I’d won the Indianapolis 500 in ’63, which earned me a lot of attention in the media. That was true pretty much everywhere, especially in Southern California because from the time I’d started racing I listed Torrance as my hometown.”

He was “honking down” the Long Beach Freeway, the 710, in a Ford Fairlane given to him by stock car owner Vel Miletich, who would be his partner in a chain of tire stores and car dealerships as well as engineer vehicles for his career with the Vels’ Parnelli Jones Racing team.

“This Fairlane had a souped-up engine with three carburetors. Vel said it would pass anything on the road; I told him in passed everything but a gas station,” Jones continued.

Admitting he was “cruising along pretty fast” when he saw the blue lights of a California Highway Patrol car in his rear-view mirror.

“I pulled over and started digging for my license and registration. I had it ready for the patrolman when he walked up to my door.

” ‘You were going pretty fast,’ he said. ‘Who do you think you are, Parnelli Jones?’

“Later on, I had a few incidents similar to that one, but there’s nothing like hearing a line like that for the first time. It was such a kick that for a moment I wasn’t even mad at myself for getting stopped.

“I handed the cop my papers and said, ‘As a matter of face, I am Parnelli Jones.'”

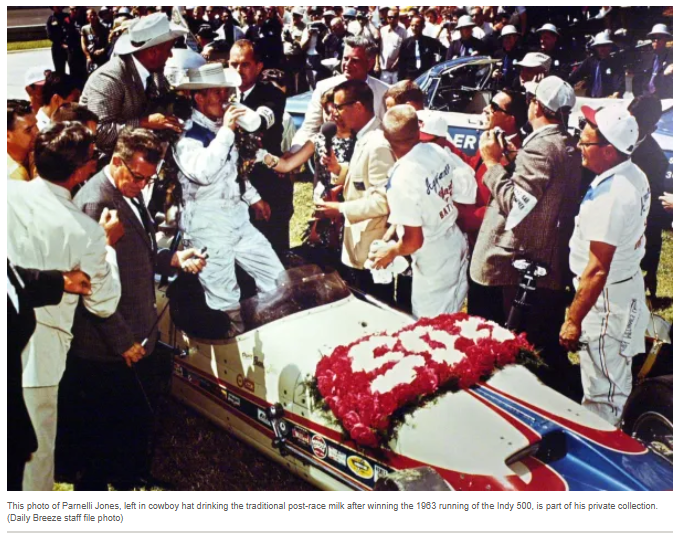

Which made for a great book title released 50 years after that ’63 Indy win, when he commandeered the No. 98 Willard Battery Special roadster owned by J.C. Agajanian that may have been leaking oil but it still slid past the competition for another piece of lore in The Greatest Spectacle in Racing.

That also opened the eyes and ears of car-crazy Southern California.

While his surname may have been a fairly common, even for a someone who uncommonly raced everything from old jalopies at Carrell Speedway in Gardena, NASCAR four-door stocks in Daytona, Trans-Am titles, even a dune buggy championship in the Baja 1000.

It was his nickname that shot him forward.

Too many knew him by his first name, Rufus. Parnell was his middle name. His mother, Dovie, named him after Rufus Parnell, a judge who she worked for in Arkansas.

When he was 17 and legally too young to race cars, he and his friends came up with a name that wouldn’t be too recognizable. His friend Billy Calder would tease him that a girl in school named Nellie liked him, so somehow Calder took Jones’ middle name and started call him “Parnellie.” In 1951, Calder was also in charge of lettering the race car. Painting the driver’s name on the door, next to their No. 66, Calder one day came up with the alias “Parnellie Jones.”

“We lost the ‘e’ somewhere along the way,” Jones adds in the preface, “but I’ve been ‘Parnelli’ every since.”

He made quick work of it.

At one point in Los Angeles’ 20th Century history, the city was the biggest racing market in the world. That was a statement made by author Harold L. Osmer in “Where They Raced: Auto Racing Venues in Los Angeles, 1900-1990,” and referenced by Patt Morrison in a Los Angeles Times story about the love of Southern California race tracks.

Santa Monica, Beverly Hills, Culver City, Playa del Rey, Saugus, Corona, San Bernardino, Long Beach, Ontario, Terminal Island, Riverside and Pasadena were home to more than 175 tracks that dotted Southern California in the early days of racing.

Agricultural Park on the site of the current Los Angeles Coliseum had the first official series of races in 1903, sponsored by the new Auto Club of Southern California.

In recent years, the Los Angeles Coliseum has been converted into a tight NASCAR track, which seemed to look something like what was the last incarnation of Ascot Park (1957 to 1970) during its days in Gardena.

The industry drivers from Southern California made their names here as well:

= Mickey Thompson: The “Hottest Hotrodder in the World” from Alhambra/El Monte set more speed and endurance records than any other in motor sports history. He set a land speed mark of 151.26 mph in 1955, and then went 294.117 mph in a twin-engine dragster three years later. At the Bonneville Salt Flats in 1960, he broke the 400 mph barrier. He also entered cars at the Indy 500. He’s in the Motorsports Hall of Fame, International Motorsports Hall of Fame and the Off-Road Motor Sports Hall of Fame.

= Stubby Stubblefield: The L.A. native was the first driver ever killed during qualifying at the Indy 500 in 1935, at age 27. He had four starts in the race, from 1931 to ’34, in the Nos. 36, 15, 8 and 5 cars. He was inducted into the National Sprint Car Hall of Fame in 1997.

= Johnnie Parsons: Winner of the 1950 Indy 500 started in open-wheel racing in L.A. in the 1940s.

= Jimmie Johnson: From El Cajon, near San Diego, winner of seven NASCAR Cup titles and 83 races. He heads a list of great California-native drivers such as Jeff Gordon, Robby Gordon, Dan Gurney, Ernie Irvan, Kevin Harvick, Ron Hornaday, Dick Rathman, Kyle Larson and AJ Allmendinger.

Then came Parnelli Jones.

With a reputation of being a bit too rambunctious behind the wheel, Jones made it to age 90 when he died in Torrance in June of 2024. His survival instincts were part of his DNA.

A 1970 column by the Los Angeles Times’ Jim Murray started: “When they’re young, some guys go out with girls, go bowling or dancing, or play pool or see movies. Parnelli Jones used to smash cars into trees. The only thing he liked better than a good wreck was a good fight. … Parnelli Jones left a legend around the race tracks of America but they remember him on the old pre-dawn games of ‘chicken’ along Sepulveda, too. Parnelli won them all. If he hadn’t he wouldn’t be here today becaue the word was Parnelli wouldn’t turn left at the edge of Niagara Falls.”

Jones was born in Texarkana in 1933 but his family moved to California during the Depression looking for agriculture jobs in Hemet, then Fallbrook, then moving to Torrance when he was 7, the oldest now of three kids.

Jones used to herd cows in Palos Verdes when he was a kid, since the dairy farms where in nearby Harbor City. He said that allowed him to go rabbit hunting up on the Palos Verdes peninsula.

“We’d to hunting up to the top of The Hill with a .22,” he admitted, “and stuff you just don’t do anymore.”

Jones, who went to Torrance Elementary, then to nearby Narbonne High in Harbor City at first before circling back with his friends to Torrance High, quit school in the 11th grade. He worked in construction as a mixer of cement and a concrete finisher, and a gas station attendant and repair garage on Hawthorne Boulevard in Torrance..

Jones said Donald Nash, a former Torrance police chief, used to brag about the fact “he caught me all the time speeding.”

Jones was actually into some other kind of horse power growing up – real horses, training stallions and riding quarter horses – until “I grew too big to race them. When I turned 16, I sold my horse and bought a hot rod — a ’23 Ford T-bucket with a Model A engine — and that started the whole thing. After wrecking my car week after week, I had all this desire and no talent. So finally somebody saw something they liked in me. They saw my desire, you know, and that propelled me.”

As Jones became more skilled and strategic, he became more successful.

“I never wanted to be second best,” he said. “I saw kids who had things I didn’t. You can teach somebody to drive a race car. What you can’t teach them is the desire and will to win. You know, you’ve got to have that kick-butt-type attitude.”

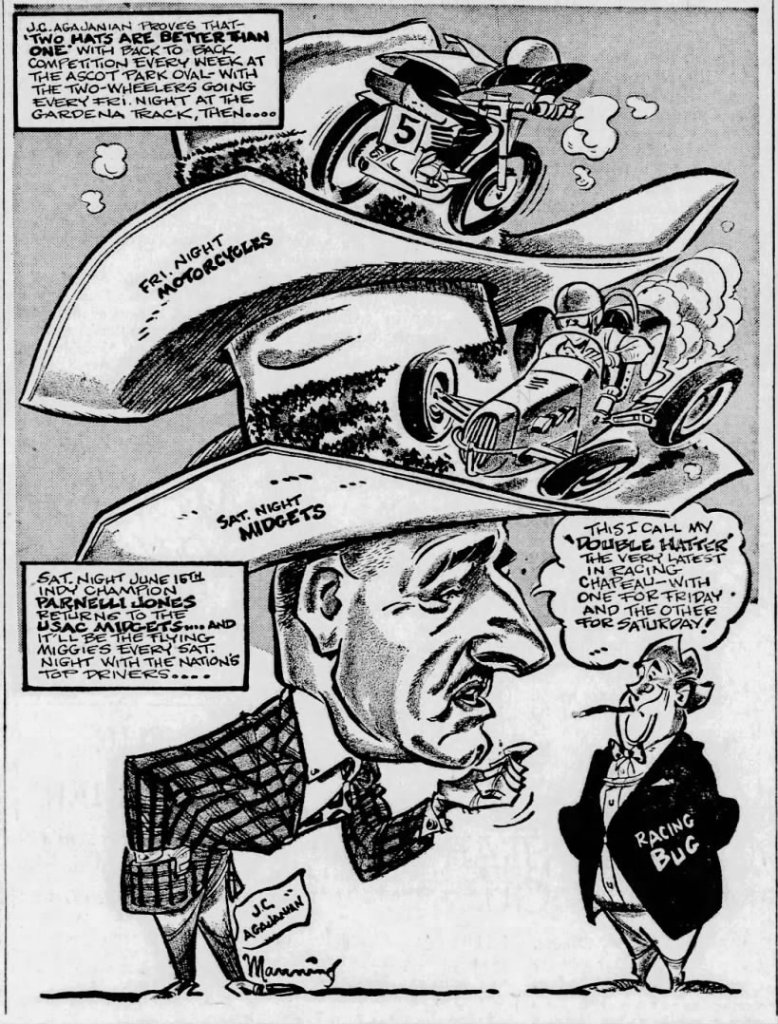

Meanwhile, there was J.C. Agajanian, a San Pedro native who wanted to be a race car driver growing up in the 1930s but instead got into promotions and owning teams. He was shielded by his Stetson cowboy hat and high-heeled boots.

Agajanian became partial to No. 98 and used that in all his Indianapolis, Sprint and Midget cars. The first No. 98 to win at Indy was Troy Ruttman in 1952 — a 22-year-old who made history as the event’s youngest winner. Jones idolized Ruttman. Agajanian also had Walt Faulkner, a driver who raced at Indy four times and was on the pole in 1950.

Jones moved onto Team Agajanian and was the Indy 500 Rookie Driver of the Year in 1961. He led the race early but finished 12th – he was hit in the face by a stone, drawing blood and blurring his vision. In ’62, he won the Indy 500 pole and ran that first-over-150 mph lap. A brake line failure slowed him after he led the first two-thirds of the race and he finished seventh.

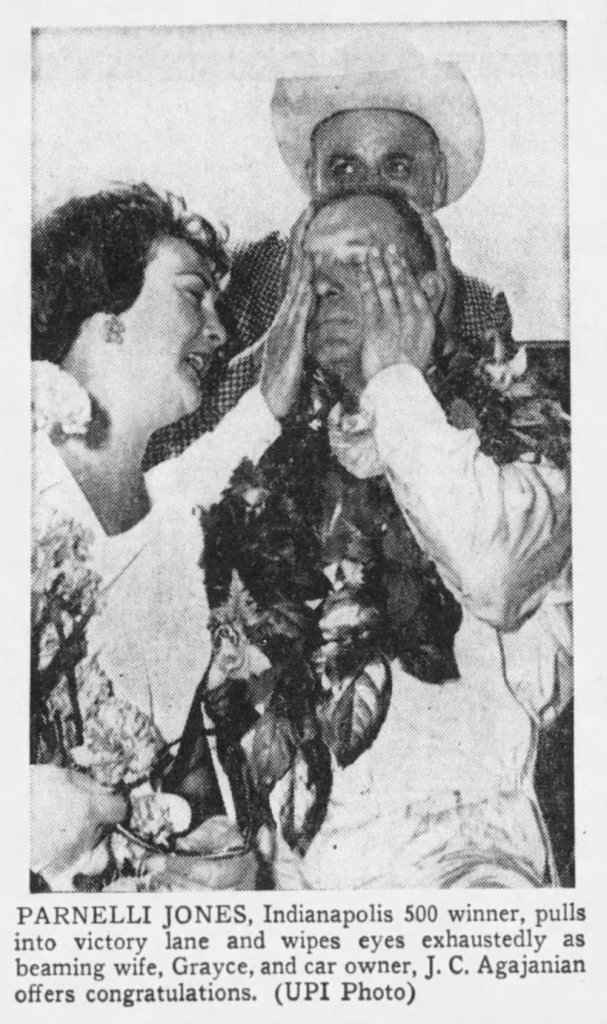

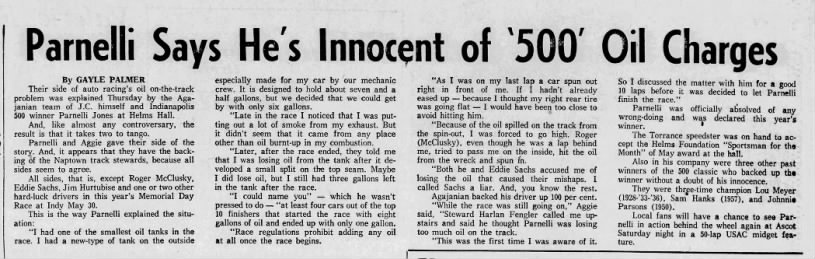

In ’63, Jones was again on the pole. To make sure this win didn’t go sideways, Agajanian’s quick thinking proved to be resourceful. Jones lead the race in the late stages, holding off Jim Clark in the controversial Lotus-Ford car. The No. 98 had a serious oil lead, and when Eddie Sachs crashed late, he blamed it on the oil spread on the track from Jones’ car. Agajanian rushed up to the starter and argued that the leak was stopped. Other car owners were upset at Agajanian’s excuses.

But as they argued on, Jones stayed in the lead and held on.

The word afterward was that since Jones was driving an American car, all the pushback came from the foreign entries that he wasn’t black flagged.

In a 1969 book called “Parnelli: A Story of Auto Racing,” author Bill Libby wrote:

“A few seconds before 2:30 in the afternoon, three hours, 20 minutes and 25 seconds after the race began, Parnelli Jones speeds his oil-splattered number Ninety-eight pearl, red and blue roadster across the strip of bricks that marks the finish line and under the checkered flag waved by Pat Vidan from his perch above the rack and the greatest Indianapolis 500 has been won.”

In the 1967 Indy 500, Jones drove for Andy Granatelli’s new No. 40 STP-Paxon Turbro Car, and was leading with three laps to go but broke down. He finished sixth.

Libby’s book created a narrative for Jones as someone who went from “dropout to millionaire,” and this would be “a stunning portrait of America’s greatest racing driver.” The blurb on the back continued: “In Spain, he would have been a matador. Instead the rugged Californian became perhaps the best driver and certainly the toughest man in the world’s fastest sport.”

The legend

At the January 1970 NASCAR Motor Trend 500, staged at the old Riverside International Raceway, Jones won the pole and set a new lap record in his ’70 Torino at 112.337 mph, ahead of Dan Gurney, Dave Pearson, A.J. Foyt, Bobby Allison, Richard Petty and Donnie Allison.

But NASCAR officials disallowed Foyt’s time, as well as nine other West Coast drivers, because they were using a limited-edition Firestone tires that the governing body ruled were not available in sufficient numbers and gave him and others an unfair advantage.

By the way, NASCAR had just signed a deal with Goodyear.

Since Jones had his chain of Firestone tire stores in Southern California, he argued that he could supply enough tires to everyone. So he showed up on race morning with trucks full of the tires he’d qualified on, offering them to the rest of the field. NASCAR still forced Jones and the other West Coast drivers to start behind the drivers that had Goodyear tires. Jones started 36th in the 44-car field with a set of “untried” Firestone ties.

That day, Jones drove spectacularly through the field. On lap 43, as he came off turn 9 and when he crossed the start/finish line, he was suddenly leading the race, passing A.J. Foyt.

As Jones drove past the grandstands, he stuck his left hand out the window, raised it upward and emphatically gave a salute with a single digit. It was directed toward the NASCAR officials, including Bill France, in the press box located atop the grandstand. The crowd erupted.

The only account one can find of this event was a waggish comment in Autoweek magazine, where it was recounted that Jones came by and let the crowd know what position he was in.

As drivers jockeyed for position, Jones also took the lead on lap 111 and held it until he suffered from a problematic clutch on the 168th of 193 laps. Foyt passed him and was declared the winner. Richard Petty was fifth. Dan Gurney was sixth. And Parnelli Jones was 11th.

The legacy

Jones retired with six IndyCar wins and 12 pole positions, four NASCAR wins in 34 starts and 25 career sprint car wins. Plus seven Trans-Am wins. And the Baja 1000.

Two-time Indy 500 winner Rodger Ward once told a Motor Trend writer: “Parnelli Jones was the most talented race car driver I have ever raced against.”

As a team owner, Parnelli Jones found victory at the Indy 500 in back-to-back years with Al Unser. Jones would ship the car back to his Torrance retail store and let people gawk over it.

It was his way of giving back to the place where he grew up. And maybe even sell a few extra spare tires.

Jones’ history of racing in Sprint Cars, Champ Cars, Midgets, NASCAR Grand National, Trans-Am, and Baja have put him in 20 domestic and international racing Halls of Fame, such as the Indianapolis Motor Speedway (1985), USAC (2012) and International Motorsports (1990).

Jones’ son P.J. raced IndyCar, NASCAR and Le Mans. Another son, Page, also raced. Jones was also fond of Jason Leffler, a Long Beach native who died from injuries suffered at a sprint car crash in 2013 at age 37. Leffler worked at Jones’ race shop as a 13-year-old kid. He finished 17th in the 2000 Indy 500 and was in NASCAR fulltime.

Agajanian kept No. 98 in circulation as co-ownership with his son, Cary, businessman Mike Curb and Bryan Herta Autosports, having Dan Wheldon use it in 2011. It was also used by Alexander Rossi in 2016.

Long after J.C. Agajanian’s Ascot Park in Gardena closed in 1990, Irwindale Speedway picked up the tradition of having a Turkey Night Grand Prix for its USAC National/Western Midget race. The race was 98 laps, in Agajanian’s honor, and gave out the J.C. Agajanian Trophy.

In 2019, Chase Briscoe paid homage to Parnelli Jones during a throwback weekend at Darlington Raceway by driving a No. 98 car.

In the afterward to the Parnelli Jones book, Mario Andretti writes:

“He remains an icon. That’s because even though his career was relatively short, he was always at the top. Parnelli was never just another driver. He was a winner. Once people get used to the idea that you’re a winner, you’re name resonates for a long time. So that’s how we all remember Parnelli: As a winner.”

Who else wore No. 98 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

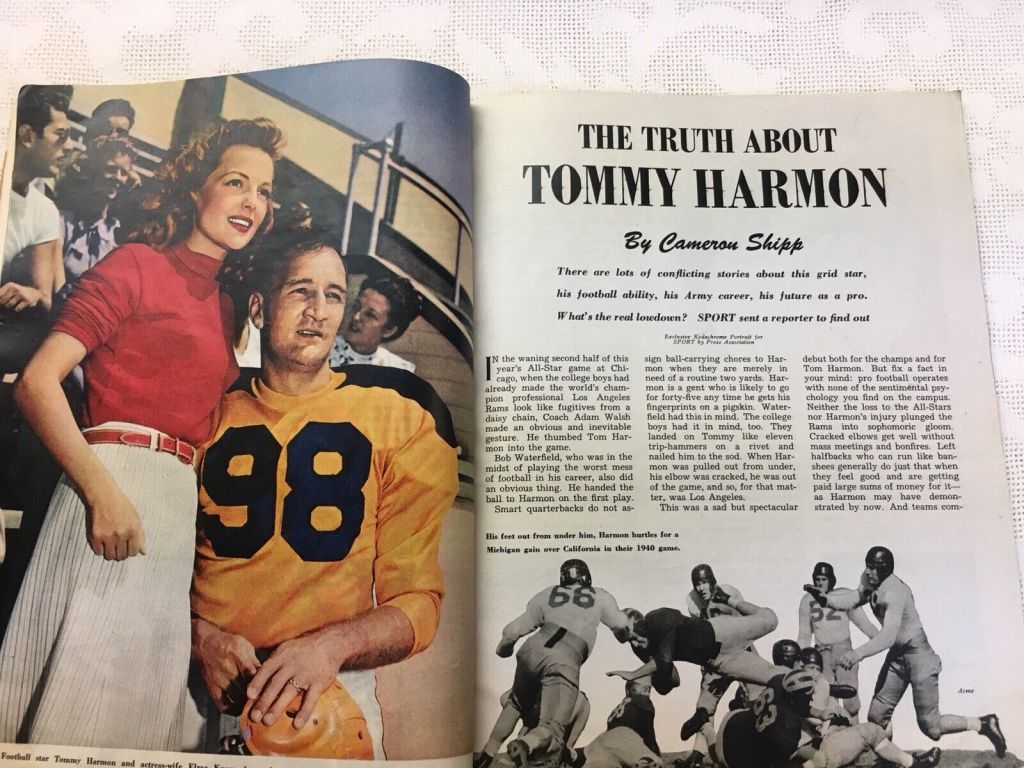

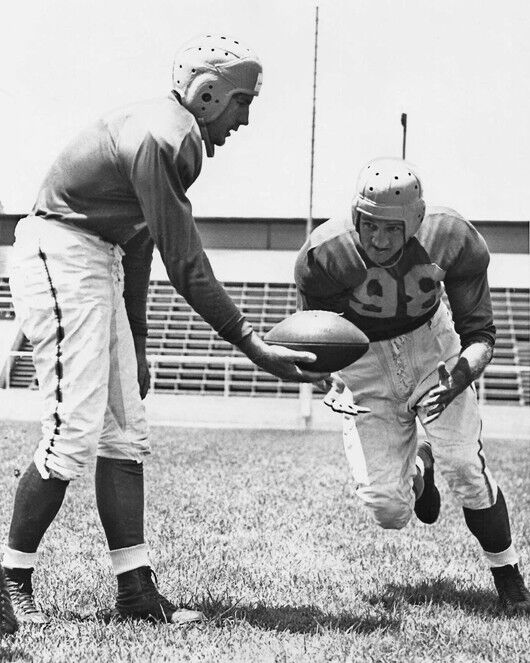

Tom Harmon, Los Angeles Rams halfback (1946-47):

The 1940 Heisman Trophy winner from Michigan — famous there as “Old 98” when he broke Red Grange’s college career record by scoring 33 touchdowns – had other ideas after his college career ended. That ending, for what it’s worth: In a 40-0 route over rival Ohio State, he ran for 139 yards and three TDs, threw for 151 yards and two more TDS, had four PATs, had three interceptions on defense, three punts that averaged 50 yards, and he had three kickoff returns for 81 total yards, playing all but 38 seconds.

The No. 1 overall pick in the 1940 NFL draft by the Chicago Bears, Harmon was drawn more to movies and radio. That started with starring as himself in “Harmon of Michigan” for Columbia Pictures. In 1941, the New York Americans of the American Football League signed him for four games. Then came a glorious service record in the Army Air Force as a World War II pilot, receiving a Silver Star and Purple Heart.

Married to actress Elyse Knox in 1944, Harmon was coaxed by the Los Angeles Rams to play for them as a 27-year-old after they moved from Cleveland to the Coliseum. Harmon had the NFL’s longest run at 84 yards. but in the Rams’ T-Formation, he broke his nose 13 times. He left after the end of his two-year contract in ’47 and became a radio broadcaster for KFI, calling Rams’ games starting in 1948. In that time, he also did more movies: 1948’s “Triple Threat,” 1952’s “Bonzo Goes to College” with Ronald Reagan, and 1953’s “All American” with Tony Curtis.

Anyone else worth nominating?

This post has so many things I hadn’t thought about in ages. Parnelli Jones Ford. J.C. Agajanian. Ascot Park and Irwindale Raceway (and all those radio ads). Shav Glick’s byline. And who knew you could once grow up herding cows in Palos Verdes?

LikeLike