This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 40:

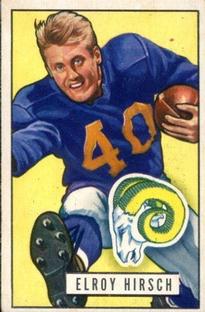

= Elroy Hirsch: Los Angeles Rams

= Frank Tanana: California Angels

= Troy Percival: California/Anaheim Angels

= Bartolo Colon: Anaheim/Los Angeles Angels

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 40:

= Bill Singer: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Roman Phifer: UCLA football

= Karl Morgan: UCLA football

= Manu Tuiasosopo: UCLA football

= John Vallely: UCLA basketball

The most interesting story for No. 40:

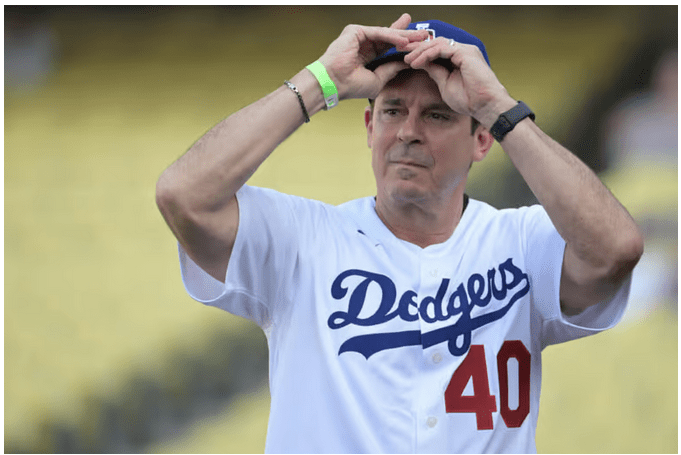

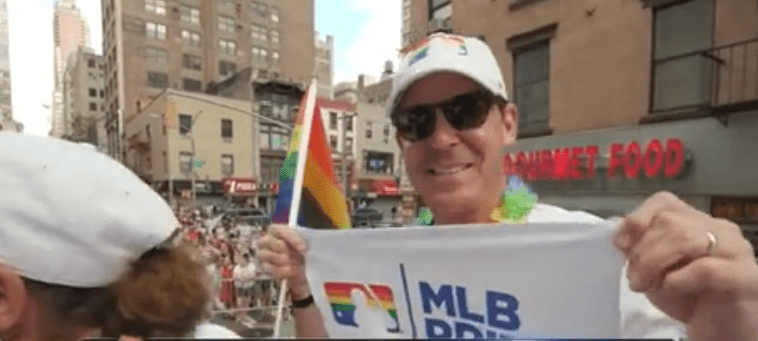

Billy Bean, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (1989), Loyola Marymount outfielder (1983 to 1986)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Santa Ana, Westchester, Dodger Stadium

******

When the Los Angeles Dodgers fumbled their way through a regrettably controversial Pride Night at Dodger Stadium in June of 2023, Billy Bean wasn’t going to shy away from any of it. He arrived in his No. 40 jersey — the number he wore during his one and only season with the team in 1989 as a reserve outfielder — and this event, however convoluted it had become, or misunderstood by those who had to have their own opinions, was going to have his positive spin.

That was likely the last time many in the organization saw him.

Just two months later, he was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia. He revealed the diagnosis during the MLB’s Winter Meetings in December to help with a “Stand Up To Cancer” fundraiser. He had been awaiting a bone marrow transplant.

After a year-long battle, Bean died at his New York home on August 6, 2024. He was 60.

The photo of Bean in No. 40 was atop the New York Times/Athletic obituary of him that helped explain how he “played a groundbreaking role in pushing MLB to reshape its relationship with the LGBTQ community.” He had been actively serving as the MLB’s Senior Vice President for Diversity, Equity & Inclusion and Special Assistant to the Commissioner as a way to amp up “visibility of LGBTQ issues in the sport and deliver education initiatives to players and front offices throughout the game.”

Bean never asked for this job. He just sort of evolved into it. As the sport did around him.

In his 2003 autobiography, “Going The Other Way: Lessons From A Life In and Out of Major-League Baseball,” Billy Bean explained how he needed eight years after he retired from Major League Baseball to finally document how painfully difficult it was to stay in that world of professional sports as he tried to find the right time, place and purpose to come out as a gay man.

He was the antithesis of the stereotypical jock: A valedictorian at Santa Ana High where he took his team to the state championship. He accepted a scholarship in 1983 to attend a Catholic university — Loyola Marymount.

Any talk of sexual exploits made him uncomfortable among his teammates, Bean wrote in his book. He found a woman, Anna, who he married and felt happy with and could have helped him in his professional journey. There was too many things missing.

“I hoped that by making my marriage a priority, I could get beyond the ‘gay thing’,” he wrote.

He couldn’t. They divorced after four years, and Bean, still a member of the San Diego Padres, set up house with his first companion, Sam, who eventually died of AIDS. Bean didn’t attend the 1995 funeral because he didn’t want to miss a game and have to explain his relationship.

Not long after, Bean was called back from Triple A to the major leagues. It was only then, as he prepared to retire from baseball he told his parents that he was gay.

A year before the 2003 book came out, Bean played himself in an episode of HBO’s “Arli$$,” called “Playing It Safe.” Bean was advising a fictional MLB player not to out himself. By 2006, he was appearing on an episode of the Game Show Network’s version of “I’ve Got a Secret.”

It was no longer a secret.

Before he was a Tiger, Billy Bean could have been a Yankee.

In the 1985 draft when Bean became junior eligible, the Yankees took him in the 24th round (one pick ahead of the Chicago Cubs taking Mark Grace) and offered Bean a $55,000 bonus. The team then raised the stakes to entice him after he did well in a summer league. The New York Mets had also drafted Bean’s roommate, pitcher Tim Layana, in the fifth round. But Bean promised LMU coach Dave Snow he would return for his senior year. Bean’s step-dad reminded him of that promise. Layana came back as well.

Bean, wearing No. 44, returned spark the Lions to a 50-15 season, three weeks ranked at No. 1 and a trip to Omaha, Neb., for the College World Series tournament. Layana had most of LMU’s career pitching records, and Bean graduated with many school and conference hitting records — hits (290), RBIs (203), and total bases (449). He also hit .403 with 67 RBIs junior and .355 and 68 RBIs as a senior.He would be inducted into the LMU Hall of Fame in 1992.

Detroit took Bean after his senior year in the 1986 draft with the 99th overall pick (fourth round, six spots before Kansas City took Bo Jackson; Layana went to the Yankees this time, in the third round). Bean’s grit and determination became a favorite of manager Sparky Anderson, which helped when Bean got his first big-league break in April ’87 after Kirk Gibson was hurt. Called up from Triple-A Toledo, Bean hit lead off and played left field, collecting four hits in his debut at Tiger Stadium against Kansas City’s Mark Gubicza in a 13-2 triumph to help Jack Morris get the win. The next day, Bean got two more hits against Bret Saberhagen.

A year after their 1988 title, the Dodgers were having a bit of a struggle. The hangover ’89 season saw Gibson injured again, along with Mickey Hatcher, Kal Daniels and Chris Gwynn. Dodgers GM Fred Claire scooped up the 25-year-old Bean in a mid-season trade.

“It’s a dream come true,” Bean said at the time he joined the Dodgers. “I think (the Dodgers are) gonna get more than they bargained for. I’ve got a lot of confidence in my abilities. I just hope it can come through. Players react differently to a major league situation. I’d be a liar if I said I didn’t have jitters those first few games. It takes time to be comfortable and let it out, show what you can do. You’ve got to learn how to focus, just play baseball and let it happen.

“I hope to play here a long time. There’s always gonna be distractions (in your hometown). I was a Dodger and Angel fan, but the Dodgers were the best team — Garvey and all those guys, they were the idols. There’s that mystique of Dodger Blue. I’ve got to separate myself from that. I’m a major league ballplayer. I’ve got to do my job first, play some solid baseball. Maybe over the winter I’ll have time to sit back and reflect on that stuff.”

Dodger broadcaster Vin Scully enjoyed how Spanish-language voice Jaime Jarrin referred to Billy Bean as ”Guillermo Frijoles” on air, and frequently repeated it. Bean said he felt wanted. In his first start as a Dodger, batting second and playing center field, he went 2-for-4 against the Astros in the Houston Astrodome. The next day he was in the lead-off spot with Mike Scott on the mound against Fernando Valenzuela. In the season-closing game in Atlanta, Bean went 3-for-4, batting third and playing right field to help Orel Hershiser win his 15th game (as he pitched 11 innings of the 12-inning triumph).

Truth is, Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda had already had gone through a squeamish experience with a gay player — Glenn Burke, who then had a relationship with his son, Tommy Jr. If Bean could sense that Lasorda wasn’t the one he could feel comfortable with giving off any an inkling of his sexual orientation, it was understandable.

Back in the Dodgers’ minor-league system in ’90 and ’91, where he hit .295 and .297 at Triple-A Albuquerque, Bean was snatched away by the Angels in a minor league draft transaction. They sent him to Triple-A Edmonton and released him. The San Diego Padres picked him up to go to Triple-A Las Vegas. They gave him eventually the most playing time he had seen with any franchise — 176 games over three seasons, before he retired at age 31. Before he retired, he got to be a teammate with his boyhood idol, Garvey, in San Diego.

In 1999, four years after his final game, Bean’s story finally came out. He spoke to the Miami Herald in 1999 first. He spoke more in depth to the New York Time’s Bob Lipsyte, saying he did not want to ”embarrass what I hold sacred — my family and baseball.” It took the unexpected deaths over an eight-year period of his step father, of his first partner and then of Layana as the result of a car accident before Bean could address his sexuality, leave the game and accelerate the process of coming out.

”I missed the funeral of one of my best friends,” Bean said, who had disconnected from that circle of friends. ”Tim would have understood if I had told him. I began to think, I’m not living some horrible existence, I’m proud of my life. Where do I finally draw the line and just say, ‘Accept me or don’t?’ ”

Eventually came a December, ’99 appearance on ABC’s “20/20” with Diane Sawyer.

This all meant that Bean became the first major league baseball player to publicly discuss his homosexuality to this extent and the first athlete in a major American team sport to do so since the football player Dave Kopay, who came out in 1975.

In a 2016 interview with LMU Magazine, Bean admitted that when the school retired his No. 44 in 2000, it was more than just a special moment.

“It changed my life. I thought because I was gay that my own school would not want my name on any wall. It was a very emotional moment. A few years later, Lane Bove, senior vice president for Student Affairs, invited me to lunch and showed me the LGBT Student Services office on campus, and that was incredible. The generosity in allowing kids to be who and what they are enables them to live a healthier and better life. Many of us, unfortunately, haven’t been in the time and place to be our best self yet, and that is a gift I would love to give everybody if I could.”

Also asked he thought of how his experience might have given him a better appreciation for what Jackie Robinson achieved.

“I think about Jackie Robinson just about every day. His life experience and his legacy are part of the reason why the expectations of baseball are so high in terms of social responsibility.”

One of the most important things Bean was able to accomplish as part of the MLB’s first Ambassador for Inclusion in 2014 was help Milwaukee Brewers minor leaguers David Denson, a former Bishop Amat of La Puente High and South Hills of West Covina standout, become the first member of an MLB organization to come out as gay in ’15.

When Bean revealed his leukemia diagnosis last December, he told USA Today’s Bob Nightingale: “Mentally, it’s a new challenge. I’ve been fit my whole life, but there have been some nights where I can not recognize how my body feels. … I’m not angry, I’m hopeful.”

Arizona Diamondbacks manager Torey Lovullo, who played at UCLA when Bean was at LMU and became Bean’s roommate in the Detroit Tigers’ system in the late 1980s, knew about Bean’s status. His team was fighting its way to the World Series as the unlikely representative of the National League. Bean encouraged him to focus on the team instead of him.

“Billy has always been such a giver,” said Louvullo at the time. “He’s one of the best human being I ever met. He’s just always been available to everyone, touching everyone. I want the world to know what a great human he is. I know it’s not in his DNA to allow people to give back to him. Well, now it’s time for him to catch all of that love. I want the world to know it’s for him.’’

The response to Bean’s passing has been predictably sweet and simple.

Outsports.com’s Ken Schultz wrote about how Bean left an “heroic legacy for gay athletes.” Editor Cyd Ziegler wrote about how Bean built bridges and “had a powerful effect on the lives of countless people, not just in baseball but across the sports world.”

New York Yankees manager Aaron Boone, as the team noted a moment of silence for Bean before their double header at Yankees Stadium against the Angels, said: “I think in creating the position that the commissioner created for him several years ago, I think created more tolerance in our sport and understand that there’s a lot more similarities between us than when we always focus on the differences. Billy was definitely a guy that definitely helped bring people together and move the needle in that regard, and he’s somebody that will be missed.”

Bud Selig, the MLB commissioner who brought in Bean 10 years ago, said this: “I knew that we had to hire somebody who understood diversity and what it really meant. Everybody recommended Billy, and I met him and I liked him immediately. You couldn’t help but like him. Somebody called him a hero in the paper, and that’s true. He believed in his causes — multiple causes — and he wasn’t afraid to tell you, and he wasn’t afraid to do something about it. Not always easy in this world, but Billy did it. So to me, he’s a hero, and I’m grateful for everything he did.”

Selig added that when Bean joined MLB, there wasn’t a guidebook for what his role would entail. Selig urged Bean to do the job as he saw fit. Brewers fans probably remember Bean’s role in counseling then-Milwaukee closer Josh Hader after insensitive social media posts came to light in 2018. Bean was by his side as Hader gave a tearful apology for those posts.

“I hired him because he was the right guy,” Selig said. “He knew what he wanted to do, I knew what I wanted him to do, and he went and did it.”

Current MLB commissioner Rob Manfred added: “He made Baseball a better institution, both on and off the field, by the power of his example, his empathy, his communication skills, his deep relationships inside and outside our sport, and his commitment to doing the right thing.”

In the Washington Post, national baseball writer Chelsea Janes did a piece titled “Billy Bean was a safe space in a sport that couldn’t find a safe space for him” and wondered where the sport goes forward as trying to stay inclusive without him.

“Are we closer to what Billy was hoping for, that if someone was comfortable enough to talk about the things he was unable to inside of an active major league clubhouse?” asked Lovullo. “I don’t know,” he said. “But if a player came to me and had a story like Billy had, I would get up, tell him I love him and give him a big hug.”

When the San Francisco Chronicle’s Susan Slusher wrote an obituary about Bean, she noted how he had been the second MLB player to ever come out. The first, Glenn Burke, also once played for the Dodgers (we have honored him with the No. 3 in this series) and died of AIDS-related complications in 1995.

Bean was at the forefront of making sure Burke was never forgotten. In 2014, on the same day MLB announced that Bean had been hired as the league’s first ambassador for inclusion — with Burke’s sister, Lutha Davis, holding his hand at the news conference — the league also recognized Burke as the game’s first gay pioneer.

“I’m absolutely heartbroken,” Davis told the Chronicle after hearing of Bean’s passing. “Billy and I had a very special bond, and he was very kind. You couldn’t help but love him. The world has lost a genuinely good guy.”

In a “Letter to Glenn Burke,” Bean once wrote in 2020: “I often think how my life and career might have been different had we known each other. I believe we would have become great friends. We lived the same isolation and fears while playing a sport we love and doing so during a time that was much different and less accepting. … I wish I could sit down with you and tell you all about the ways that baseball has changed for the better, and how we would have never arrived at where we are without you.”

As of late 2024, those in the MLB hierarchy wasn’t sure who might step up to fill Bean’s role as the LGBTQ ambassasor. A New York Times/The Athletic piece ran a story with the headline “How Do You Replace One of One?” about the Bean legacy.

Los Angeles Angels outfielder Kevin Pillar, born in the West Hills area of the San Fernando Valley and a graduate of Chaminade Prep and Cal State Dominguez Hills, talks in the story about how his friendship grew with Bean in 2017. Pillar, then an outfielder with the Toronto Blue Jays, had been suspended by MLB for yelling a homophobic slur that incited a bench clearing brawl. Part of the conditions for the return of Pillar, who is Jewish and a year earlier had established the Pillar-Lambert Scholarship in Accounting at Tel Aviv University in Israel to honor of his late maternal grandfather Ed Lambert, were to meet with Bean for some sensitivity training.

Bean forgave Pillar.

“I wish I could have met him under different circumstances,” said Pillar, who played for the Dodgers in 2022 and was inducted into the Southern California Jewish Sports Hall of Fame. “You live and learn in this game. I was fortunate to have gotten to know him. He’s definitely a big loss for the game. … I’m not sure they’re going to fill the position. But in terms of filling the position of someone that’s part of the LGBT community (and also) a professional baseball player, that doesn’t happen very often. He knew what it was like to be in a major league clubhouse. He also knew what it’s like to be gay.”

Bean will remain a hero to many in the LBGTQ community, especially as his last position for MLB was a Senior Vice President for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion.

In 2015, Bean also wrote a first-person piece for MLB.com about the joy he found given a chance to put a uniform back on with the New York Mets to help with spring training– even if it created a story with second baseman Daniel Murphy pushing back on Bean’s appearance:

Inclusion means everyone, plain and simple. Daniel is part of that group. A Major League clubhouse is now one of the most diverse places in sports. It wasn’t always that way, but we can thank No. 42 for that. So in his honor, with a little patience, compassion and hard work, we’ll get there.

A personal connection story

Barry Zepel, the former LMU sports information director, shared this about how he came to know, respect and find a friend in Billy Bean:

In my first five years (1979-80 to 1983-84) as the SID for LMU, my closest working relationship and friendship in the Athletic Department was with longtime Head Baseball Coach Marv Wood. We worked late and most often were the last to leave the office on weekday evenings. As a result, we often went out to dinner together.

Marv hit the recruiting bonanza prior to the 1981-82 academic year when he signed both star outfielder Billy Bean of Santa Ana High School and Tim Layana of Loyola High School (Los Angeles) to scholarships. Billy and Tim became best friends in the fall of 1981. With Marv wanting to ensure that Billy and Tim were comfortable and happy, he would invite them on occasion to join him for dinner, and I often tagged along. That’s how I got to know both student-athletes.

As a one-person office (except for a few hours per week of help from a few student assistants), it was otherwise difficult for me to get personally acquainted with many of the other baseball players — at least until the completion of basketball season in late February or mid- to late-March. By that point, baseball is well into its season. For their four years at LMU, I was able to form a pretty close bond with both young men.

With each year, Billy and Tim grew as team leaders and star performers on the field of play. After the 1983 baseball season, LMU began planning for the construction of a new baseball stadium, to be built in the same location as the old diamond and stands. Unfortunately, the construction was delayed several times and the new facility was not ready for the start of the ’84 campaign. That meant that the Lions were forced to play most of their games on the road and at neutral sites. That led to a disastrous 11-41 record and Coach Wood was unceremoniously dismissed. Dave Snow, an assistant coach in the highly successful Cal State Fullerton baseball program, was hired as LMU’s new head coach.

With the new stadium ready, the Lions enjoyed a much improved ’85 season as Billy and Tim continued to shine as players. Both players reached All-America status, as the Lions won the West Coast Conference championship, beat UCLA and Pepperdine at the NCAA regional in Westwood, and went to LMU’s one and only College World Series in Omaha, beating nationally ranked Louisiana State University in the first round, before being eliminated after the next two games. All in all, the Lions wrapped up an incredible 50-15 record in ’86. While in Omaha, both Billy (by the Detroit Tigers) and Tim (by the New York Yankees) were drafted and each signed with those teams shortly thereafter. They kept in regular contact with each other, and I briefly was able to have limited contact with them thereafter. Billy was assigned to the Tigers’ Double A team in Glens Falls, NY.

As I had already planned to spend part of that summer of ’86 with relatives residing in nearby Massachusetts and make a side trip to Cooperstown, NY, a full day’s drive from their home, I decided to extend my travels to Glens Falls. I was the first person from California to visit Billy there while he was that team’s starting center fielder. I got a motel room not far from where Billy was sharing an apartment with one of his Glens Falls teammates. I took him and his teammate to dinner after his game and then Billy and I connected again for breakfast the next morning. Before we went our separate ways, he asked me if I could purchase several pairs of Franklin brand batting gloves. He said he was unable to get them through his team nor find them at any of the area’s sporting goods stores. I checked a bunch of stores outside the Boston area and finally found several pairs of Franklin batting gloves at a large store… I think it was Dick’s Sporting Goods. I spent the balance of my last three days scouring the area for these gloves. I didn’t want to disappoint Billy! I mailed them to him.

Those gloves must have helped him. During the following season of 1987, Billy was promoted to Triple A and then to the major league team in Detroit. In his very first game with the Tigers, Billy set an MLB debut record with four hits (in six at-bats). Unfortunately he had his “ups and downs” going back and forth between the majors and the minors, before being traded by the Tigers to the Dodgers for the 1989 season. I remember hearing that when he reported to the Dodgers clubhouse — for a road game — that first day, Tommy Lasorda thought he was their bat boy. Billy said: “No sir, I’m your new center fielder.”

With the help of then-Dodgers PR man Brent Shyer (a one-time student assistant of mine when I was the sports info. director at Cal Poly Pomona 12 years earlier), I was able to have a brief conversation with Billy before an ’89 game at Dodger Stadium. That was the last time I had any direct communication with Billy for the next 30 years. I followed his career via newspaper box scores and, and then years after his playing days were over through a book he wrote and the resulting media interviews. As the Internet and social media continued to develop, I would occasionally try to reach him through whatever online platforms seemed most appropriate.

I saw that he had a Facebook account through his vice presidency with the MLB Office of the Commissioner in New York City. I sent him a Facebook Private Message in 2019 and he responded, telling me to let him know when I was in New York, and we could get together for lunch. Having scheduled to get together with family in upstate New York, and my wife wanting to see a Broadway show in Manhattan, Billy and I finally reunited. At lunch he provided me with a few souvenirs that any baseball fan would love to have. I wanted to provide him with something he liked but couldn’t get in New York nor anywhere on the East Coast. Upon returning home to the Seattle area, where I now reside, I asked him if he likes See’s Chocolates. He said that he loved them, with his favorites being See’s Chocolate Covered Molasses chips and and their Chocolate Cremes Bordeaux. With a See’s store a few miles from my home, I mailed two boxes of each flavor to his Manhattan apartment.

We had several more visits, both in New York City, and in Seattle, where he was helping the Seattle Mariners prepare to host the 2023 MLB All-Star Game, Home Run Derby, and other annual All-Star weekend events in his capacity as MLB’s senior vice president and right-hand aide to the commissioner. He offered tickets to each of those events to my wife and I, and we of course gladly accepted. This was in July. I then saw him about six weeks later, in late August, back in New York while visiting family upstate. I hand delivered another “load” of his favorite See’s candies to him at his office.

Less than a week later, a fatigued Billy Bean would find out a diagnosis for why he was so tired: He was suffering from leukemia. Of course I didn’t find out about that diagnosis until early December, with the start of the Baseball Winter Meetings. As an avid baseball and Dodgers fan, I was anxious to learn about any pending trades and free agent signings, as well as the related and rumors. On the first day of those meetings, MLB announced its “Stand Up to Cancer” campaign, and noted that Billy and another MLB staff member were fighting the disease. Of course that wasn’t the news I would ever suspect someone like him to be battling. From that point we kept in regular contact via text. Like so many of his friends, I offered myself as a bone marrow donor if found to be physically qualified. He told me that donors who are not family must be between the ages of 18 and 40. I’m 70.

Should I be sending him See’s Chocolates? I didn’t know. I found out that he could eat anything that would taste good to him; anything that could help him regain as much weight as possible. He lost so many pounds due to the disease and lack of appetite due to the chemotherapy treatments. I still asked him, and he was so much looking forward to receiving more of those candies. Indeed, they were among the few things that still tasted good to him. I sent several more shipments of the candies his way. We traded text messages on June 20. On that day he said: “Thank you Barry. Struggling this week. Feel like I am stuck and my treatment is going so slow. It’s hard not to get angry and frustrated. The meds are taking a toll on my body.”

I last texted him on July 24. I didn’t hear back from him again. Then, on Aug. 6, I saw MLB’s announcement online reporting that Billy had died. I couldn’t believe it. I still can’t.

Who else wore No. 40 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

Elroy Hirsch, Los Angeles Rams running back/receiver (1949 to 1957):

Crazylegs and all, Hirsch was still “the embodiment of swivel-hipness” when came to Los Angeles after three seasons wearing No. 80 for the Chicago Bears. As a right end, the former Wisconsin and Michigan college star had his NFL breakout season was 1951, when the Rams experienced their first L.A. NFL championship thanks to the exploits of quarterbacks Norm Van Brocklin and Bob Waterfield: Hirsch had a league-leading 1,495 yards receiving on just 66 catches for 17 touchdowns and a long of 91 yards, adding up to 124.6 yards a game. And that was during 12 games. The three-time Pro Bowl end/flanker left at age 34 enough of a star to be named No. 93 in The Athletic’s list of “The Football 100.” That’s where his “swivel-hipness” description came into play as Dan Daly, a football historian, called him as much. “When he was coming at you, you didn’t know which way he was going to go, and he did it with great speed. He was a great runner after he caught the ball. Just watch the highlights from that era and see how well he tracked the deep ball. Norm Van Brocklin, in particular, loved to throw deep. He would adjust to the ball in flight so well, even when he had a guy on his hip, he could make the catch with extended arms, and the first few steps, he was off and nobody was going to catch him. Most of the good ones will slow up just a little bit to catch the ball, but he never did.”

The glamor boy Hirsch also starred in a couple of Hollywood movies — one of them his own life story — and just three years after his playing days were over, he was the Rams’ general manager, lasting until 1969.

There was also the story about Hirsch’s “last game.” On the Pro Football Hall of Fame website, there is the story: Fact or Fiction? Hall of Famer Elroy Hirsch was nearly stripped naked by fans after a game. Seems to have some truth. It goes this way:

Hirsch originally hinted at retirement in 1954. His “final” game came during the Rams’ 35-27 win over the Green Bay Packers in the season finale on Dec. 12, 1954. The Rams honored their great star with a halftime ceremony.

Per usual, he shined for the Rams as he caught five passes for 119 yards in the game. Then, a bizarre scene unfolded after the final gun sounded. As Hirsch began making his way off the field one last time, he was engulfed by a large crowd of young fans. Fearing for his safety, he began removing parts of his uniform and tossing it in an effort to disperse the group of overzealous admirers.

“They actually started to trample me,” he once recalled. “So I took off my jersey and threw it one way. And a pack of them went off after it. I took off something else and threw it the other way and got a few more out of the way. Little by little, I bartered my way off the field.”

By the time he arrived in the locker room “semi-nude,” as described by a sportswriter, Hirsch was down to his shorts and pads around his waist and tape on his ankles.

After injuries depleted the Rams lineup, Hirsch was convinced not to retire and played three more seasons. Lucky for him, he walked off the field at the end of the 1957 season without incident.

His name came up when the Los Angeles Rams acquired star linebacker Von Miller near the end of the 2021 season. Miller couldn’t wear the No. 58 he had for years in Denver, so he sought out the No. 40 he wore in college. He asked the Rams if they could take Hirsch’s No. 40 out of retirement and let him wear it. The thing is, the number wasn’t even retired. Miller instead got permission from the Hirsch family and wore it as he played in the Rams’ Super Bowl LVI victory in February, 2022 on their home turf. As it stands, the Rams still have officially retired only eight numbers: 7 (Bob Waterfield), 28 (Marshall Faulk), 29 (Eric Dickerson), 74 (Merlin Olen), 75 (Deacon Jones), 78 (Jackie Slater), 80 (Isaac Bruce), and 85 (Jack Youngblood). Hersch? Time will tell.

Frank Tanana, California Angels pitcher (1973 to 1980):

“Tanana and Ryan and two days of cryin'” became the follow up to “Spahn and Sain and pray for rain.” The left-handed compliment to the right-handed Nolan Ryan in their parallel lives ran concurrent for seven seasons, and Tanana emerged as the AL leader in strikeouts in 1975 with 269 (9.4 per game) and the AL ERA leader in ’77 at 2.54, to go with a league-best seven shutouts and 20 complete games — but just 15 wins and a league-leading 8.3 WAR. His three straight AL All Star appearances from 1976 to 1978, from age 22 to 24, were the highlight of his eight Anaheim seasons that began as a 19-year-old. It should be noted that he had a 102-78 record with the Angels, but a sub-.500 record everywhere else he went (eight seasons in Detroit, four in Texas and one each with the Mets, Yankees and Boston Red Sox) to complete a 21-year career. He was traded, at age 26 and in his prime, with Joe Rudi to the Red Sox in 1981 in a deal that brought Fred Lynn to Anaheim. So there’s that. For the record, Tanana gave up 448 homers over his career, the most ever by an AL pitcher, and his 240 wins are the most by any left-hander that never had a 20-win season. He finished 11th all time in wins by a left-hander. In the 1999 Hall of Fame voting, which gave enduction to Ryan, George Brett and Robin Yount, Tanana did not even get one vote.

Troy Percival: California/Anaheim Angels relief pitcher (1995 to 2004):

The four-time AL All Star was on the mound converting his seventh save in seven opportunities during the post season when the Angels clinched their one and only World Series title. He amassed a franchise-best 316 saves in 579 games during his 10 years. His best season: ’02, with a 4-1 record, 40 saves, 68 strikeouts and a 1.92 ERA. A sixth-round draft pick out of UC Riverside as a converted catcher, Percival went back to coach the team from 2015 to 2020, having also coached at his high school alma mater, Moreno Valley.

Bartolo Colon: Anaheim/Los Angeles Angels pitcher (2005 to 2007):

He arrived with the Angels as a free agent in ’04, switched to his favorite No. 40 after Percival left, and won the AL Cy Young Award in ’15 with a 21-8 record and 3.48 ERA in 33 starts. The four seasons in Anaheim were a fraction of the 21 years with 11 teams he had in a career that spanned from 1997 to 2018, but that ’15 season was the only one when he was a 20-game winner, amassing 247 total.

Have you heard this story:

Jesse Chavez: Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim pitcher (2017 and 2022):

Nothing trivial about this MLB fact: What player has been traded the most times? It’s Chavez, and it ended at 11. It’s been documented (although at the time of the story, his journey was far from over). When Chavez officially retired on July 24, 2025, at age 41, after 657 appearances over 18 seasons with nine different clubs, it was three days after the Atlanta Braves had released him for the sixth time. With Atlanta, he was part of his only World Series title team.

Born in San Gabriel, Chavez was first drafted out of Miller High in Fontana, but he passed. Posting a 24-7 record and 1.94 ERA at Riverside City College, he accepted the Texas Rangers’ offer after they took him in the 42nd round in 2003. After three seasons in Texas’ system, Chavez was traded to Pittsburgh, which then traded him to Tampa Bay, which then traded him to Atlanta, which then traded him to Kansas City.

The Dodgers got him in a trade with Tampa Bay in 2016. The Angels, who signed him after the 2016 season after the Dodgers released him, would eventually release him after 2017. The Angels again signed him as a free agent in spring training 2021, but released him a month later. The Angels got him in a trade with Atlanta in August of 2022, kept him for about three weeks, released him, and the Braves signed him back. In both official stops with the Angels, he wore No. 40 — a 7-11 record in 21 starts (38 appearances) in ’17, and a 1-0 mark in 11 games (with a 7.59 ERA) for the Angels in ’22. When he was with the Angels in 2017, it was the greatest contract he ever had at $5.7 million, which came after the $4 million he got with the Dodgers. Chavez said being with the Dodgers and Angels gave him a chance to drive his kids to school at his year-around home in Pomona.

His stop with the Dodgers for 23 games in 2016 (1-0, 4.21 ERA) saw him wear No. 58. How did he endure? “I don’t know. It all depends on how people want to look at it,” said Chavez in 2022. “I’m just a good guy or a bad guy. It all depends. I feel like I’ve been on the good side.”

When he retired, he said: “This has been a great ride and way more than I ever expected from a 42nd- round draft pick. I was given a gift early on, I understood but it was, ‘How am I going to make it last?'”

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Los Angeles Lakers center (1976):

Now, how was it that on Nov. 24, 1976, for a Lakers’ game in Denver, Abdul-Jabbar didn’t have his No. 33 and had to wear a No. 40 jersey with no name on the back? Likely a lost laundry issue. He scored a game-high 28 points going up against the Nuggets’ Dan Issel, but the Lakers lost 122-112. Time to discard that old thing. Lakers who would wear No. 40 before or after that time: Jerry Chambers (1967), Dave Robish (1978-79), Mike McGee (1982-86), Sam Perkins (1993), Antonio Harvey (1994-95), Travis Knight (1997-2000) and Ivica Zubac (2017-19), who had, among his nicknames, “Zu Alcindor.”

We also have:

Bill Singer: Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1964 to 1972)

Roman Phifler: UCLA football linebacker (1987 to 1990), Los Angeles Rams linebacker (1991 to ’94)

Karl Morgan: UCLA football nose tackle (1979 to 1982)

Manu Tuiasosopo: UCLA football defensive tackle (1975 to 1978)

John Vallely: UCLA basketball (1968-69 to 1969-70)

Roger Craig: Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1958). Also wore No. 40 in Brooklyn Dodgers and No. 38 for Los Angeles Dodgers from 1959 to 1961.

Bill Lee: USC baseball pitcher (1964 to 1968)

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 40: Billy Bean”