This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 43:

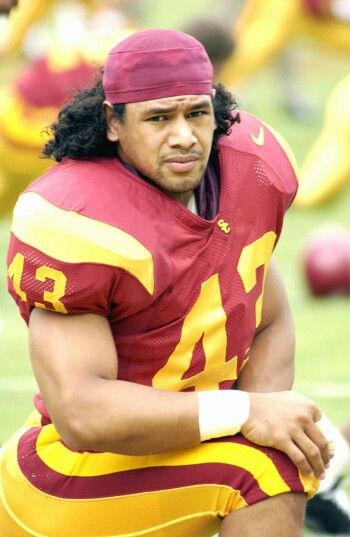

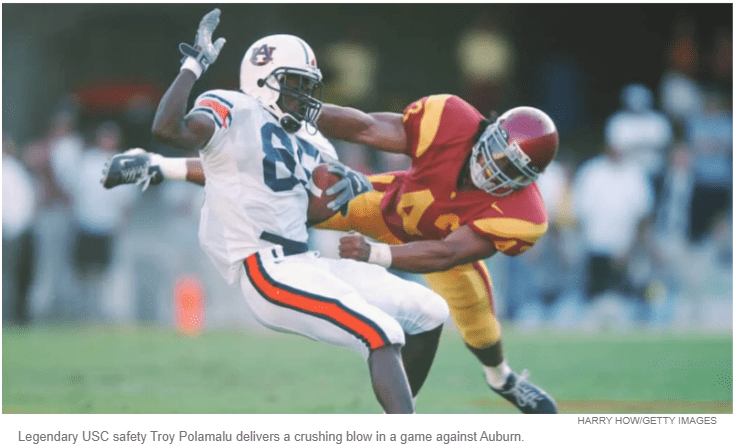

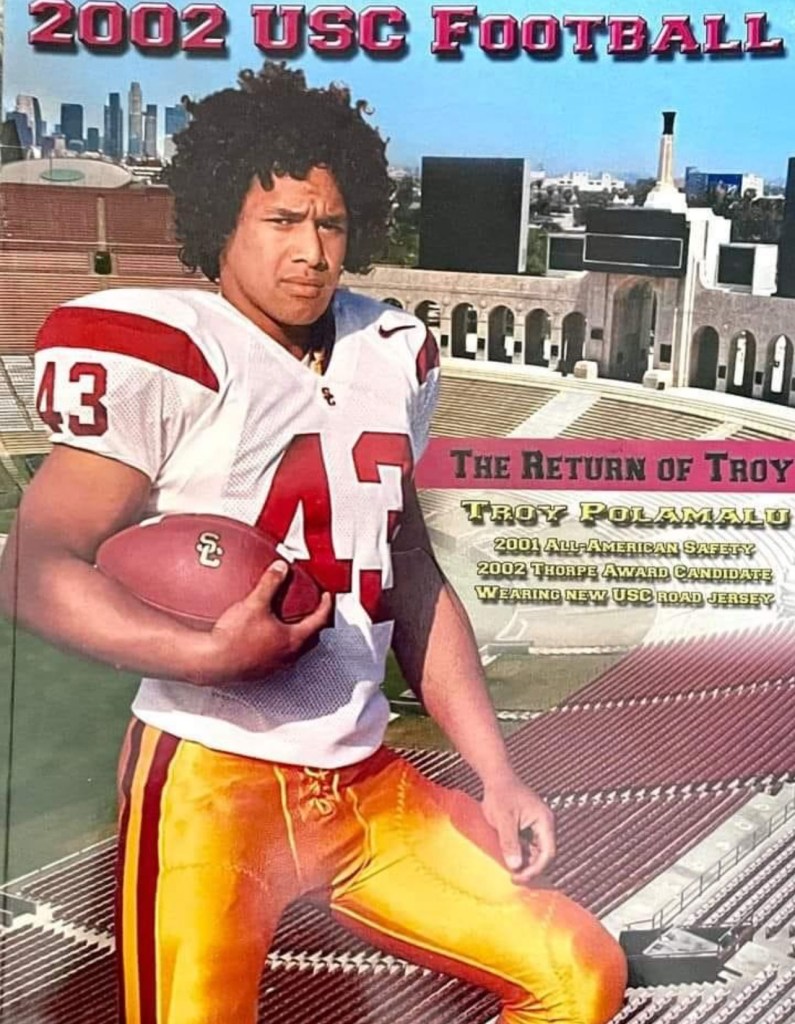

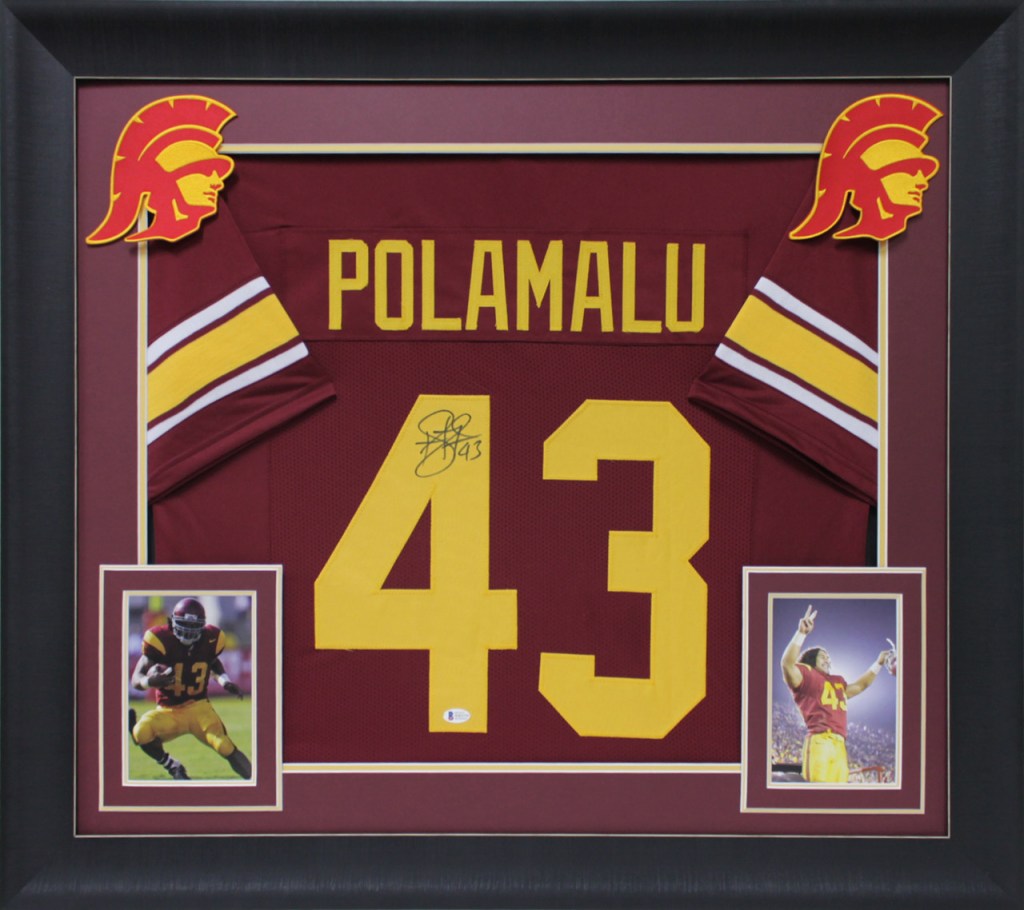

= Troy Polamalu, USC football

= Raul Mondesi, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Mychal Thompson, Los Angeles Lakers

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 43:

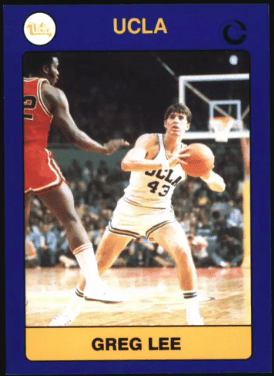

= Greg Lee, UCLA basketball

= Rick Sutcliffe, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Dave Ball, UCLA football

= George Brunet, California Angels

The most interesting story for No. 43:

Troy Polamalu, USC football safety (1999 to 2002)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Garden Grove, Santa Ana, L.A. Coliseum

The best chance Troy Polamalu had for survival when he was a kid was to move out of Southern California. His mother agreed.

So when he was 9 years old, with an incredible amount of self awareness, Troy went to live in Oregon. His Uncle Salu Polamalu would be a major influence on him.

Eventually, the next best chance Troy Polamalu had for self fulfillment as an talented, passion-filled athlete when he was a teenager was was to come back to Southern California. His family agreed.

So when he graduated from high school in Oregon, his Uncle Keneti Polamalu, better known during his USC football days as a running back named Kennedy Pola was a major influence on his finding a spot on the Trojans’ football roster.

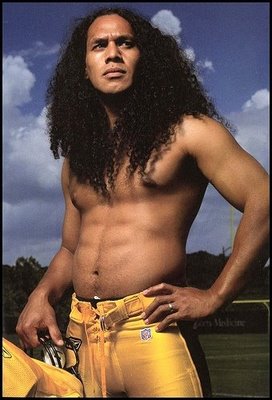

It didn’t take all that long before Polamalu stood head and shoulders above his Trojan teammates. Aside from his signature head of hair.

Dynamic. Acrobatic. But with his soulful calmness, integrity and dedication to family and spirituality. He also became another link in a line of influential and admired Polynesian/American Samoan players in the region’s storied history history.

Troy Amuma was his name at birth, the youngest of five children to Sulia Polamalu and her husband Sitala “Tommy” Amuma. The couple came from American Samoa and joined up with friends and relatives in Orange County, a Polynesian-expat community, about five years before Troy’s 1981 birth in Garden Grove.

Once his parents divorced, and his father was out of the picture, and the only other male in his household, older brother Kaio, was not a great role model, in and out of jail. His three older sisters, Sheila, Lupe and Tria, weren’t much better — all becoming mothers while they were in high school. Troy was a self-described “street rat” growing up in Santa Ana, surviving amidst the family on welfare and not a lot of discipline.

“I still have this picture in my head where, as a kid, I’m just wondering what’s going on,” Polamalu told GQ magazine in 2011. “I’m in first grade. My brother’s in the backseat of a police car, waving for me to open the door. What am I supposed to do?”

One experience that still resonates, thought, was when he and brother Kaio played one-on-one football, then teaming up for two-on-two games against older kids in the neighborhood.

“When (Kaio) and I played, it was Soldier Field, I was Walter Payton and I would run towards him and jump over him, and he would launch me up even higher and I would do flips and land,” Troy told DK Pittsburgh writer Dale Lolly. “So, when we started challenging people, playing full-contact, tackle football. They would look at me like, ‘Man, this kid is only six, seven years old.’ My brother was a teenager. I was playing against 20-year-olds. We always won. That was my first real interest in football.”

Kaio, who had been kicked out of Mater Dei High, ended up playing at Rancho Santiago JC as a defensive end, was a team MVP and transferred to Texas-El Paso as a fullback. His life turned around.

As author Jim Wexell best explains in his excellent 2023 oral history book, “Polamalu,” it was a family trip to rural Tenmile, Oregon, about 80 miles south of Eugene, where Troy fell in tune with the peaceful family life displayed by his mother’s brother, Salu, his wife, Shelley, and his cousins, especially Brandon.

Sulia Polamalu allowed Troy to move, and she stayed in Santa Ana with his sisters. Salu Polamalu, the eldest of ten siblings, adhered to the strictures of Fa’a Samoa, the Samoan way, the old tribal code of respect for family, church, and community. He was a disciplinarian.

“That was a hard decision for my mother,” Troy told The (Roseburg, Ore.) News-Review in 1998. “I just thank her and I thank God for sending me up here. I don’t think I’d be who I am now if I had stayed down in California.”

When he was starting in the fourth grade in Oregon, Troy asked his uncle if he could use their family name, Polamalu — like his mother, and his uncle — instead of Amuma. It was done, although Troy wouldn’t officially make Polamalu until a legal name change in 2007. That was another remarkable part of his maturity and transformation.

“One thing I learned from being in Southern California and being raised the way I kind of lived, you get to know a lot about people,” Polamalu once said. “You get to know quickly what people’s intentions are. If they’re good people, if they’re bad people. I kind of developed that quickly. … The way bad people reacted to me (in Oregon) was much different. I was also able to experience a different kind of love in a way. I had families that I was a part of in Oregon that I never had a chance to be a part of in Southern California. There was a mother and father, they both had jobs, they both went to college. Not only being raised by my aunt and uncle, but I got to spend a lot of time in my childhood in Oregon months and months at a time with other families and being able to be integrated with them.

“I had rooms at other people’s houses. At my own house, I still slept on the floor. It was culture shock negatively, but more on the other side of it, I was able to experience the beautiful aspect of it.”

When he was in sixth grade, Polamalu admitted in the GQ story that he committed his final crime: He stole a Bible from a gift shop, to give himself a scriptural underpinning to his newfound faith.

At Douglas High in Winston, Ore., wearing No. 35 on the football team with the Trojans nickname, he showed his “street rat” mentality and dexterity. As a junior, he was an all-Oregon first-team player and MVP at his school, putting up 1,040 yards rushing with 22 touchdowns, the second year in a row he exceeded 1,000 yards. He also pulled in 310 yards as a receiver and also recording eight interceptions and 65 tackles on defense. The team went 9-1. By his 1998 senior season, he only played four games because of injury, but still made numerous all-state teams as a prized recruit, putting in 671 yards rushing and nine TDs to go along with three interceptions. He was an honor student as well.

But he also played basketball. And baseball. Hitting .550 as a senior center fielder, MLB scouts were interested. Like, the Dodgers. Rod Trask, Polamalu’s baseball coach at Douglas High and also for American Legion summer ball, recalled traveling with Polamalu to Los Angeles for a tryout.

“The Dodgers were thinking about drafting him after his senior year,” Trask said. “We stayed for a week and Troy did tremendous (with the tryout) — and he also visited USC while we were down there. He told (the Dodgers) at that time he was going to play football and Troy was not selected in the draft because of that.”

(For what it’s worth, among the Dodgers’ notable picks in that 1999 draft included outfielder Jason Repko in the first round, who, as a 25-year-old, got the big-league call in 2005; and outfielder Shane Victorino in the sixth round, eventually taken out of the Dodgers’ system by Philadelphia, and then became an All-Star and Glove Glove winner. There was also a third baseman named Albert Pujols who went in the 13th round to St. Louis.)

The reason Polamalu visited USC was because another uncle, Kennedy Polamalu, a USC assistant coach at the time convinced Trojans head coach Paul Hackett to give his undersized nephew a scholarship opportunity.

But USC almost lost out in that lottery.

Keneti Polamalu — aka Kennedy Pola when he was a fullback with the Trojans in the 1980s — had been the running backs coach under Rick Neuheisel at the University of Colorado in ’97 and ’98. Troy had been to the Colorado camp to see what was happening and wanted to be a running back. But when Neueisel left and took the head job at the University of Washington, Keneti Polamalu went to San Diego State as a linebackers coach in 1999. The next year, he was back at USC.

“It’s probable that in today’s world of high school evaluation camps and national all-star games, somebody like Polamalu might not be as readily overlooked or vastly undervalued,” wrote ESPN’s Greg Katz in 2015.

Hackett told DK Pittsburgh that the official trip he made to Oregon with Keneti Polamalu to visit Troy included an “unbelievable” welcome.

“They were so friendly,” said Hackett. “We sat out on the back porch and talked. And Troy barely said a word. He was just so quiet. You wondered about how his play would translate. He was at such a small school. It was easy to look at the kids from the schools around L.A. and figure out how they would make the transition. With Troy, we weren’t as sure. A lot of the coaching staff didn’t want Troy because of that. But Kennedy and I were adamant about him.”

When Polamalu made a visit to USC, Hackett added: “I remember we would talk about him as a staff, but Kennedy would leave the room because he didn’t want people to think he was pushing for Troy because of his relationship.”

After a Hackett recruit fell out, a spot was open, and Hackett gave it to Polamalu.

“I believe God named me Troy for a reason,” Polamalu once said. “I was born to come here.”

At 5-foot-10, 206 pounds and a growing bush of black hair that gave him a distinctive identity and was attached to the nickname of “The Tasmanian Devil,” Polamalu’s Trojan career started as a backup safety and linebacker on a 5-5 team. He missed four games with a concussion. But his blocked punt against Louisiana Tech in the season’s final game while on special teams that showed what instincts were embedded.

In the 2000 season opener, the sophomore’s interception return for a touchdown in the second quarter against No. 22 Penn State announced his presence. It gave No. 15 USC a 20-3 lead in an eventual 29-5 win. The number of yards on the return: 43. Polamalu also delivered a vicious hit on San Jose State receiver Casey Le Blanc that sent the ball flying 20 yards downfield. He recorded 14-tackle games against both Arizona and Notre Dame but the team would stumble to a 5-7 mark in Hackett’s last season as head coach.

“I always try to lay myself out on the line and sacrifice my body for the team,” he explained in an interview with the USC football website. “Spiritually, I try to be thankful for all I’m blessed with. If I’m hurt I try to think of the times when I should have been thankful.”

First-year head coach Pete Carroll made Polamalu a team captain for his junior season on a squad would finish 6-6. The final two games of the season were most memorable for Polamalu — a blocked a punt and had an interception in a 27-0 upset against No. 20 UCLA at the Coliseum, and, i the Las Vegas Bowl, a career-best 20 tackles, three for a loss, during a 10-6 loss against Utah. For the season, he had three picks and was USC’s team MVP, and first-team All-American.

As a senior in 2002, Polamalu was voted USC’s Most Inspirational Player. The team had its first 11-win season since 1979 and a No. 4 national ranking when it went to the Orange Bowl.

A pre-game hamstring injury kept him limited in the Trojans’ victory over Iowa. He still recorded 68 tackles, nine for losses, and had four pass deflections.

Career stats: 36 games started, 278 tackles, 29 for losses, six interceptions, 13 pass deflections, four blocked punts, three touchdowns.

When the New York Times in 2020 created a list of “the best players to wear every jersey number in college football history,” Polamalu was the No. 1 pick for No. 43.

Polamalu’s USC experience also included:

= He lived in a Victorian house on 24th Street close to campus with teammates Carson Palmer (the eventual Heisman Trophy winner), Maleafou MacKenzie and Lenny Vandermade. They just referred to the place as the “1013.”

= He actually made the 2000 Trojans’ baseball team wearing No. 43 for Coach Mike Gillespie between Hackett’s departure and Carroll’s arrival — but after taking some batting practice against Mark Prior, Polamalu didn’t feel up to adding that to his classload.

= He met his future wife, Theodora Holmes, the sister of USC tight end Alex Holmes, dating her during his senior season.

= He went back to USC to finish his degree in history in 2011 at age 30. When he started at USC, he was angling toward a degree in education because of a desire to be a role model for younger kids.

“I decided to finish what I started and walked that stage today not only because it was very important to me personally but because I want to emphasize the importance of education, and that nothing should supercede it,” Polamalu said at the time.

When he was inducted into the USC Athletic Hall of Fame in 2018, his bio included: Known for his fearless hitting and flying tackles along with his flowing black hair, he was one of the greatest safeties in football history.

When he was inducted into the College Football Foundation Hall of Fame in 2019, his bio highlighted that he was a finalist for the Jim Thorpe Award as the best defensive back in the nation and was a member of the Pac-12 All-Century Team.

When he was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2020 to cap his 12-year career with the Pittsburgh Steelers, who made him a first-round draft pick in 2003, it is noted that he played on two Super Bowl championship teams (including SB LXIII in 2009 — there’s that No. 43 again). He was also the NFL Defensive Player of the Year in 2010 (one of only five safeties in NFL history with that honor), four-time first-team All-Pro, eight Pro Bowl picks and on the NFL’s 2000s All-Decade team.

And his Hall of Fame bust reflected his hair-style choice.

The story also goes also that Polamalu was the first No. 43 to make it into the shrine. He and Class of 2020 fellow inductee Cliff Harris, that is. It is reflected in the name of his website: Troy43.com.

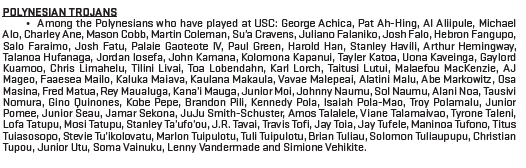

In USC’s 2024 home opener against Utah State, redshirt sophomore Jayden Maiava became the first Polynesian to play quarterback in Trojans’ history. By the 10th game of the season, in a Big Ten Conference 28-20 win over Nebraska at the Coliseum where he threw for three touchdowns and ran for the game-clincher, Maiava became the first Polynesian to start as a quarterback in USC history.

“You know, growing up, I’ve always watched USC football, and just being able to be in the shoes that I used to watch, it was definitely electrifying,” Maiava said afterward he completed 8 of 11 passing for 66 yards and improvised a deft 7-yard reverse field TD run. “It was definitely a blessing.”

Maiava, an Hawaii native who transferred to USC from Nevada-Las Vegas, wears the “808” facemask that Heisman Trophy winner Marcus Mariota did while at the University of Oregon. Other Polynesian quarterbacks such as the Miami Dolphins Tua Tagovailoa and Oregon’s Dillon Gabriel also wear the facemask that pays homage to their state’s 808 area code.

With Maiava’s appearance as a starter, USC’s sports information department researched the school’s history of Polynesian players and came up with some we might have not even considered:

On the 2025 Trojan roster, it’s noted there are 15 players of Polynesian decent on the roster. During the season, Apple TV debuted a promo video collaboration with USC football for its streaming series, “Chief of War,” starring Jason Momoa. In the video, centered around USC’s Polynesian heritage, Momoa addresses Maiava and the Trojan football team.

The establishment of Hawaii-based Polynesian Football Hall of Fame, where Polamalu was inducted in 2016, also allows for catching up on the history of who came before him, and after him, in celebrating the heritage.

= Charles Ane, Jr.: A USC two-way tackle and single-wing quarterback also attended Compton College and played six seasons in the NFL with Detroit. A 2007 inductee into the USC Athletic Hall of Fame, he was voted into the Polynesian Hall of Fame the same year as Polamalu.

= Junior Seau: Full name: Tiaina Baul Seau, Jr., the USC All-American linebacker in 1988 and ’89 and became a first-round, fifth-overall pick of San Diego after his junior season. He was also nicked the “Tasmanian Devil.” He died at 43 in 2012.

= Herman Wedenmeyer: A halfback out of Saint Mary’s College who was fourth in the 1945 Heisman voting, was drafted by the Los Angeles Rams in 1947 as a first-rounder, then played a season for the rival Los Angeles Dons of the All-American Football Conference in 1948. He made his way into acting on “Hawaii Five-O” as Sergeant Duke Lukela.

= Al Lolotai: An offensive lineman out of Weber Junior College who was the first Samoan player in the NFL (Washington, 1945), before going to the AFFC’s Dons (1946 to 49).

= Harry Field: An offensive tackle from Hawaii and Oregon State who was the first of Polynesian ancestry to play in the NFL (Chicago, 1934 to 36) and then with the American Football League’s Los Angeles Bulldogs of 1937 as an All-Pro. Field started on a 1933 Oregon State team that tied and undefeated USC squad in a game using just 11 players the entire game. The “225-pound Hawaiian” Field was described by a Los Angeles Times reporter as “tougher than a cafeteria steak.

= Mosi Tatupu: The USC running back who is the namesake of the college football award for special teams player of the year. Also played for the Los Angeles Rams in 1991. His son, Lofa Tatupu, played linebacker at USC.

= Riki Ellison: Known as Ricki Gray as a USC linebacker in the 1970s, he wsa the first player from New Zealand and of the Maori Ancestory from the Maori Tribe Ngai Tahu to play in the NFL, including a time with the Los Angeles Raiders (1990-92).

= Manu Tuisosopo: The UCLA two-time All-American defensive tackle from St. Anthony in Long Beach played in the 1976 Rose Bowl winning game for the Bruins and was a first-round draft pick by Seattle. His son, Marques, played quarterback in the NFL.

= Frank Manumaleuga: The UCLA linebacker out of Banning High in Wilmington went to San Jose State after playing just one game for the Bruins — injuring his knee in the season opener against Tennessee in 1974 as a freshman, making 25 tackles.

= Rey Maualuga: A four-time Rose Bowl participant (and 2008 Defensive Player of the Game), Maualuga became the seventh Trojan inducted into the Hall as part of the Class of 2026. Ninth in the ’08 Heisman voting, Maualuga was also the school’s first Chuck Bedarik Award winner and an All-American first-team honoree. He said he picked No. 58 to carry in a tradition by Lofa Tatupu (2003 to 2004). Maualuga had a nine-year NFL career, eight with Cincinnati.

Polamalu’s legacy goes far deeper than some Head & Shoulders hair-care commercials. Polamalu and his wife established the Troy & Theodora Polamalu Foundation, which pays tribute to his American Samoan heritage. He supports the Fa’a Samoa Initiative, set up a medical clinic in Samoa.

“I have some Trojan lineage … being part of that family is very special,” Polamalu said when he was about to be inducted into the USC Athletic Hall of Fame. “To be someone to play and follow the footsteps of that Polynesian lineage … and even just from the academic side to those that earn scholarships from the islands. Just connecting with that community and just being a Trojan as a whole, it has been really special to represent that because you look at all the names that are attached to (USC) from a football perspective, the influence on politics, on architecture, on business. It’s really nice to be connected to that family.”

When Troy Polamalu did his Pro Football Hall of Fame induction speech, one of the first people he thanked was his uncle Keneti.

“My uncle instilled in me an authentic respect and passion for the game,” he said. “His intensity has inspired not just me, but countless athletes, to revere and love the game, at all costs. Uncle, you’re a true coach, not just in sport, but in life.”

His uncle was truly moved.

“Man, I couldn’t stop crying. “He didn’t have to say anything about me, it was just the moment. Not only for him, but for my family, my culture. Just wish that my mom and dad, my older brother Salu — who he lived with in Oregon — were around to see it.”

Adding context to the American Samoan experience, he added: “It’s a very poor country. It’s very family-oriented, the village pretty much. It’s a Matai system. My dad was the Matai [or chief] and basically, you took care of the whole village. And that culture has continued all the way through our lives. The humility and the service, that’s part of the culture. You take care of your family, you stay humble and you put your head down and go to work. You don’t have to talk about it, you don’t have to brag about it, you just do your job.”

Those who watched him in college can’t forget what they witnessed.

“Some of us were not only fortunate to watch him play in college, we were lucky enough to cover him and discover he was just as special off the field as he was on,” columnist Steve Bishoff once wrote.

“It was always difficult to believe this athlete who threw his body around with such disregard on the grassy floor of a football stadium could look up at people with such soft, kind eyes, away from it. You’d watch the vicious tackles, then a couple of hours later, you’d listen to that calming voice in the locker room. Or observe him interact with other players or with young kids who loved to crowd around him.

“He was the ultimate football anomaly. A young man whose helmet-jarring hits knocked down ball carriers and whose kind, soothing soul warmed the hearts of everyone who was around him.”

Bishoff also recalled before Polamalu’s last home college game at the Coliseum, coach Pete Carroll called him “an amazing football player and an amazing person.” Bishoff recalled a few games earlier in the USC locker room when an elderly gentleman in a USC windbreaker with a grandson approached Polamalu in front of his cubicle.

“You don’t know me,” he said, identifying himself as a former Trojans athlete from years back, “but I just wanted to tell you how impressed I’ve been not only by the way you play but by the way you conduct yourself on and off the field. You are the perfect role model for this program. It’s been a pleasure to observe you over these past few years.”

Bishoff concluded: “That gentleman could have been speaking for thousands of loyal USC supporters back then. And now. You know, looking back, somebody definitely knew what he was doing naming him Troy.”

Who else wore No. 43 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

Greg Lee, UCLA basketball guard (1971-72 to 1973-74):

His presence on the Bruins’ ’72 and ’73 teams, as well as playing all four years with Bill Walton and Keith Wilkes, made Greg Lee all the more recognizable, even though he was the L.A. City Section Player of the Year at Reseda High was the starting point guard as a sophomore during their 30-0 record as he averaged 8.7 points a game. “I think you have to be a real student of the game to appreciate the way Bill plays,” said Lee during his sophomore year about Walton in a March, 1972 Sports Illustrated story. “We are only now beginning to realize how good he is. With Bill back there on defense, the rest of us can afford to gamble, and we can cheat getting out on our fast break.” As a junior Lee set an NCAA championship game record with 14 assists, dumping it into Walton as he set records himself against Memphis State to cap another 30-0 season. He would join Walton for a season with the NBA’s Portland TrailBlazers. As a professional athlete, Lee may also be better known for his beach volleyball talent, playing with another former Bruin, Jim Menges, winning 13 straight tournament titles from 1975 to ’76. Lee died of a long illness at 70in 2022.

Mychal Thompson, Los Angeles Lakers forward (1987 to 1990-91):

The No. 1 overall pick in the 1978 draft actually wore No. 00 in his first game after the Lakers GM Jerry West made a mid-season deal for him with San Antonio. But as the backup for Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Thompson provided some durability and agility. And helped the team to two NBA titles in ’87 and ’88. He also provided a sense of humor with his Bahamanian point of view on life, which he continues to expound upon as a Lakers radio color analyst, a position he has had since 2003. Thompson and his son, Klay (with Golden State in ’15, ’17, ’18 and ’22) are one of five father-son duos to have each won an NBA Championship as a player.

Raul Mondesi, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (1993 to 1999), California Angels outfielder (2004):

The 1994 National League Rookie of the Year (.306, 16 homers, 56 RBIs in 112 games), leading into his only NL All-Star appearance (1995: .285, 26 HRs, 88 RBIs) finished out his time in L.A. with a 33 homer, 99 RBI season in ’99. His salary jumped from $109,000 as a rookie to $9 million at the end of his run. But he was packaged him in a deal to Toronto for Shawn Green. Somehow he only won two Gold Glove Awards in his career, both in L.A., in ’95 and ’97. He ended up wearing No. 43 his entire 13-year MLB career with seven teams. The story goes that when Mondesi was traded to Arizona at mid-season in 2003, he gave new teammate Miguel Batistia a Rolex watch to get him to yield No. 43 to him and take No. 25 instead.

Rick Sutcliffe, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1978 to 1981): Having worn No. 48 when he pitched in one game as a 20-year-old in ’76, Sutcliffe came of age in ’79 as a 17-game winner with 242 innings pitched and an NL Rookie of the Year Award. In ’80 and ’81, however, he was inconsistent and was left off a spot on the ’81 split-season playoff roster. That caused him to disrupt the feng shui of manger Tommy Lasorda’s office. “I picked up Lasorda’s desk and slammed it and I grabbed him by the throat and threatened him,” Sutcliffe once explained. “I lost it.” He would go on to be an All-Star in Cleveland and the Chicago Cubs, including the NL Cy Young for a 16-1 record in 20 games over the last half of the 1984 season.

Dave Ball, UCLA football defensive end (1999 to 2003): The 6-foot-6, 280-pounder led the NCAA with 16.5 quarterbacks sacks his senior season, and also left the Bruins as its all-time sack leader with 30.5 to earn All-American honors. With his twin brother, Mat, Dave once made a play that caused UCLA broadcaster Chris Roberts to exclaim: “Now there’s a twin Ball sack!”

Have you heard this story:

George Brunet, Los Angeles/California Angels pitcher (1964 to 1969):

Not to focus on how he led the American League with 19 losses in 1967, followed up by a league-high 17 losses in ’68 during the “Year of the Pitcher.” It’s just that, those numbers boldfaced on the back of his baseball card, means he achieved something. Burnet still had a 24-36 record over those two seasons despite an ERA of about 3.00 in 73 starts.

When the Angels sold him off to the expansion Seattle Pilots in 1969, becoming fodder in Jim Bouton’s book, “Ball Four,” (Bouton wrote that Brunet didn’t wear underwear so he didn’t have to worry about losing them), that wasn’t even the silliest part of his pro career. When he was released by St. Louis in 1971 at age 36, logging more than 1,400 innings in 15 MLB seasons, he was only halfway done on his journey.

After two more years in the minor leagues — where it is believed he set the record with 3,175 strikeouts while waiting for an MLB callup — Brunet found new life in the Mexican Baseball League in 1973 at age 38. He pitched for another 16 seasons with the nickname “El Viejo” (The Old Man). That included throwing a no-hitter at age 42 in 1977 for Poza Rica, where he was, by then, part-time manager for the club. By 1984 Brunet set a Mexican record with 55 shutouts. In 1981, he suffered a heart attack at age 46, and came back the next year and won 14 games for Veracruz. He was still pitching at the age of 54. That gave him 36 seasons of professional employment in baseball before another heart attack, when he was 56, killed him in Poza Rica.

“Nobody ever had more courage on the pitching mound,” his former Angels manager, Bill Rigney, told the L.A. Times on hearing of Brunet’s death. “He gave you everything he had until his arm fell off. The miraculous thing, though, is that his arm never fell off.” In 1999, he was elected into the Mexican Professional Baseball Hall of Fame, aka the Salon de la Fama.

Going back to his time as an Angel: Brunet’s SABR.com bio notes that the reason he got a chance with the team in ’64 was a trade with Houston to replace pitcher Bo Belinsky, demoted after punching Los Angeles Times beat writer Braven Dyer in a hotel altercation. Over seven starts, Brunet was 2–2 with a 3.61 ERA for the remainder of 1964. On September 5, he went seven innings in a 1-0 victory that knocked the Orioles out of first place.

In 1965, Burnet, in much better shape physically, was fourth in the AL in ERA at 2.56, winning nine (with eight complete games) and saving two. In 1967, Brunet was the Angels’ Opening Day starter and a 4-2 winner over Denny McLain and the Detroit Tigers.

In 1980, Sports Illustrated tracked down Brunet for a story, and he told a story about the time his luck was so bad with the Angels, Rigney came to the mound once to try to commiserate.

“I lost a lot of one-run games with the Angels,” Brunet said, “and Rigney used to say to me, ‘I owe you a game,’ every time he took me out. But one time I really got angry when he took me out, and we had words in the dugout. He knew enough to stop, but I just had to keep going. Finally, Rigney starts counting, ‘$100, $200, $300.’ I didn’t stop until he hit $700. Then I went in and tore the clubhouse apart. The next day I came in and wrote out a check for $700 to the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Fund.”

Ralph Kiner, Pittsburgh Pirates outfielder (1946):

The future Hall of Famer out of Alhambra High wore No. 43 in his first MLB season, not long after playing on the Pirates’ Single- and Double-A teams from age 18-to-20, then serving two years in World War II. Switching to No. 4 in ’47, Kiner hit 51 homers in age 24 season. He drew MVP votes in the first seven seasons as a Pirate as he became the youngest ever to reach 400 homers.

A bronze statue in his honor is in Almansor Park in Alhambra since 2008 with the plaque that reads:

THE CITY OF ALHAMBRA HEREWITH RECOGNIZES

ITS LEGENDARY FORMER RESIDENT RALPH KINER

For his accomplishments and contributions to the game of professional baseball and sports broadcasting, which have earned him a place in the Alhambra Hall of Fame and National Baseball Hall of Fame. Ralph Kiner grew up in Alhambra and is a 1940 graduate of Alhambra High School. He made his major league debut in April 1946 with the Pittsburgh Pirates and in 1947 gained recognition for hitting 51 home runs in just his second year in the majors. In 1949 he topped that record with 54 home runs. He led Major League Baseball in home runs for six consecutive seasons and the National League for seven consecutive seasons. He drove in over 100 runs in six seasons; he ranked first for slugging percentage three times; he was selected to play in the Major League All-Star Game for six consecutive years; he is the only player in history to hit home runs in three consecutive games; and he holds the Major League record of eight home runs in four consecutive multi-homer games. The City of Alhambra dedicates this statue and plaque in honor of Ralph Kiner, that it may serve as an inspiration to future generations of young baseball players.

We also have:

Willie Crawford, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (1964 to 1968): Changed to No. 27 in 1969 through 1975. See the entire Crawford entry for No. 27.

Ken Forsch, California Angels pitcher (1981 to 1986)

Garrett Richards, Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim pitcher (2011 to 2018)

Cleveland Gary, Los Angeles Rams defensive back (1989 to 1993)

Chuck Nevitt, Los Angeles Lakers (1984-85 to 1985-86)

Matt Darby, UCLA football defensive back (1988 to 1991)

Charlie Neal, Los Angeles Dodgers infielder (1958 to 1961). Also two seasons with Brooklyn.

Noah Syndergaard, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2023)

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 43: Troy Polamalu”