This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 61:

= Chan Ho Park, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Rich Saul, Los Angeles Rams

The not-so-obvious choice for No. 61:

= Josh Beckett, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Bill Fisk, USC football

The most interesting story for No. 61:

Jake Olson, USC football long snapper (2015 to 2018)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Huntington Beach, Orange, L.A. Coliseum

Long before he found his way onto the Coliseum turf with a huge smile on his face for the first time wearing a USC football jersey, the point person in executing an extra point, Jake Olson had already made his point.

The Trojans’ 2017 Labor Day weekend season opener against visiting underdog Western Michigan was tied 21-21 after three quarters and about to go sideways. Marvell Tell returned an interception 37 yards for a USC touchdown with 3:13 left in the game, and the fourth-ranked Trojans had some breathing room, up 17 points.

That’s when the 20-year-old Olson took a deep breath. USC head coach Clay Helton turned to the sideline and yelled his name: “Are you ready? Let’s get this done!”

The 6-foot-3, 225-pound redshirt sophomore took one more practice snap, launching the football between his legs with a rhythm and rote that, by this point, was pure and natural.

Olson put his right hand on the shoulder of teammate Wyatt Schmidt, and the two ran together more than 50 yards across the grass to where the line of scrimmage was at the peristyle end for the touchdown, and the game’s, punctuation mark. After the referee gave special instructions to both sides, he blew the whistle, Olson made the snap, the ball was placed by Schmidt, and the kick by freshman Chase McGrath was good. USC won 49-31.

“What a pressure player,” Helton said after the game. “Was that not a perfect snap?”

“It turned out to be a beautiful moment,” Olson said.

Former USC head coach Pete Carroll saw Olson go into the game and said he called Olson and said, “Hey Jakey! I’m so proud of you. I love you.”

If anyone by this point could see the good in all that happened, it was Olson.

The context

On Jake Olson’s official website he explains his story:

The last thing I saw was a flash of light.

I lost sight in my left eye before the age of one. For the next 12 years, I battled cancer in my right eye eight times. Seven times I beat it. When it came back for the eighth time, there was nothing I could do. I was going to go blind.

It was a sad feeling knowing that I had fought so hard for so long only to see the cancer win in the end. I knew I was going to have to re-learn how to do basic things that were once so easy. Putting toothpaste on my toothbrush, food on my fork, or walking around my house would all require significantly more effort. I viewed going blind as my biggest setback, but it ended up being my biggest set up.

Shortly before I went blind, Pete Carroll, head coach of the USC Trojans, heard about my story and invited me up to a practice. I was thrilled to get to go behind the scenes with my favorite team. I had no idea that Coach Carroll intended to make me a part of the Trojan family, and that watching this practice was only the beginning of a relationship that would change my life forever. Being around Coach Carroll helped remind me that nothing was impossible if you were always willing to compete and work for it. After I went blind, I became more determined than ever to not let blindness stop me from living the life I wanted to live.

I grew restless watching my high school football team play, and I knew I had to find a way back on to the field. I discovered the position of long snapping, and I worked at it until I was good enough to start for my high school team, and eventually become the first blind college player ever when I snapped in USC’s game against Western Michigan on September 2, 2017.

I am also very passionate about helping others, and established my foundation, Out of Sight Faith, to provide technology to blind schoolchildren. You can donate (to) Jake’s Out of Sight Faith Foundation. Thank you for visiting my site.

Fight on, Jake

Retinoblastoma is the official name of the rare cancer of the retina that took Olson’s left eye when he was 10 months old. It is what eventually led to the removal of his right eye when he was 12, a procedure needed to save his life with the surgery at Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles.

Before his sight was forever lost, one of the last things he enjoyed actually seeing was a 2009 USC practice, then given the opportunity by Carroll to run out of the Coliseum tunnel with the Trojan players and stand on the sidelines as an inspiration to the team.

While Olson was in surgery that would leave him blind, social workers told his parents to be concerned that he could be angry, bitter and resentful. A psychiatrist was recommended.

Six days after the surgery, he walked through a side hallway and into the USC team meeting room. “Hey, Jake’s here!” Carroll yelled, and players clapped and cheered.

When Carroll left USC to become coach the NFL’s Seattle Seahawks after that ’09 season, he stayed in touch with the Olson family. The relationships works both ways.

“He’s always blown me away, how much confidence he has and how capable he is and what a factor he is with people he meets,” Carroll said in 2015. “I just love the fact we had a chance to meet him and watch him grow up.”

Olson played center on his flag football team before he lost his sight, but he didn’t play his freshman or sophomore year at Orange Lutheran High in the city of Orange. He said he didn’t want to look back on high school and regret not playing football, so he asked Carroll what he thought.

“Well, you love the game, don’t you?” Carroll asked.

Jake said he did.

“Well,” Carroll said, “then go compete.”

Olson figured out how, with the help of teammates positioning him, to become a long snapper and he started as a senior in 2014. He had a 4.3 grade-point average, played varsity golf and sang in the school choir.

Going to USC with him was twin-sister Emma, who worked with the “Swim With Mike” program that awarded Jake a scholarship — he was not one of the 24 Trojan football recruits that season.

Jake brought his yellow Labrador retriever, Quebec, along as his guide dog.

Once he was in his new dorm room, Olson’s father, Brian, described to his son what he saw out the window: The view stretched for miles, with the grass of the football practice field clearly in sight.

Olson grinned as he heard the Spirit of Troy strike up the university’s fight song from the ground below. “This is so sick: I can hear the band,” he said.

Olson added: “I always felt like USC was my second home. When I was losing my sight, it became a place where I could find comfort and joy. And that never stopped.”

Olson would need a waiver from the NCAA to suit up for his first practice in 2015 under then head coach Steve Sarkisian, and nothing was guaranteed about actually playing in a game. He wore an orange No. 17 jersey at the time.

“We are happy that Jake has the opportunity to wear a USC jersey and perhaps even join his teammates on the field this fall,” said Dave Schnase of the NCAA said at the time.

After allowing him to snap in some spring games, Olson had to wait two seasons before everyone was confident he could get into a game. He did it wearing No. 61, previously worn by his favorite player, center Kris O’Dowd.

The moment

Before that 2017 opener, USC’s Helton put in a call to Western Michigan coach Tim Lester to make sure they were on the same page if and when this could happen.

“I give him all the credit,” Lester said of Helton. “That’s not an easy conversation. He was just being honest about a player he really cared for. He said he was gonna call every coach (this season) and just hope he gets it done. … He was just very nice in asking and he said he understood if I didn’t want to do it. He wasn’t forcing it down my throat, by any means.

“I didn’t think it was a hard decision at all. It was bigger than the game.”

As Olson tweeted out: “Tomorrow I walk out onto Howard Jones Field not as a fan or honorary member, but as a player for the USC Trojans.”

Teammate Wyatt Schmidt added: “From the outside looking in, you’d think he’d be a little different, and I think before he came, we thought that as well. But once he got here, just a day in, he’s a normal kid, does normal things. That’s what I think a lot of people don’t see, and that’s what we’ve had the pleasure to get to know Jake.”

By the 2018 season, Olson added 50 pounds of muscle and weight so see if that might increase any NFL considerations. Helton also got Olson into USC’s ’18 opener, a 43-21 win over UNLV at the Coliseum — he snapped on the Trojans’ final extra-point attempt with 1:38 to play.

While that was happening, Olson made headlines with even more daring feats — driving a car for the first time at a NASCAR track, jumping off a high-dive platform, posting a video on Twitter showing off his quarterback skills.

“I think that sports have given me a platform … so I could prove myself to others,” he said in a 2018 story posted on CNN. “I can go out there and have a place where I can show others that yes, I’m blind, but that doesn’t mean I don’t belong out here or that doesn’t mean I can’t perform out here.”

Earning a business degree from USC in the spring of 2019, Olson started a company called Engage, helping athletes and celebrities book speaking engagements — because it was something he needed himself.

If the COVID pandemic stalled his business, Engage grew almost 10-fold by 2021 as the NCAA expanded its name, image and likeness (NIL) rules.

“It’s scary devoting your whole life toward something that you have no idea if it may or may not work out,” Olson said of his business in 2021. “And that takes a lot of courage. It’s the same thing, kind of, going through cancer, blindness. You have no idea how it’s going to work out.”

Olson has stayed close with Pete Carroll in discussions about future projects. In August 2019, I caught up with Olson at the ESPY Awards in downtown L.A. to talk about the ways athletes have used the media to tell their own stories and expand their brand.

In a story for the Sports Business Journal, Olson told me: “People have come out of the woodwork — let’s make a movie and whatever — so I’ve signed with UTA (United Talent Agency) to control the process … and just pump the brakes on all that. There’s ample time to do any of that. I’ve enjoyed a relationship with ESPN since they were doing stories on me 10 years ago, and having so many stories done on me. What’s cool for me now on social media is letting people know more about my character, poking fun at myself, posting funny videos. Any way athletes can invite people to see their whole, colorful personalities is cool.”

Olson’s sense of humor regularly reveals itself on social media. On Olson’s Instagram and Twitter accounts — @JakeOlson61, again incorporating the No. 61 — he posts at the top: “It’s not what you look at that matters, it’s what you see.”

In 2024, he used his Instagram account to post his engagement to be married, as well as report that his longtime companion, Quebec, had died.

Quebec is with him on the cover of his first book in 2014, when he was 16: “Open Your Eyes: 10 Uncommon Lessons to Discover a Happier Life.” He has been working on another book about his life.

Olson remains driven — including participating in the U.S. Adaptive Open and in long-drive golf contests.

Wrote Orange County Register columnist Mirjam Swanson in a March 2024 story: “He’s a reminder that what’s happening on those playing surfaces goes deeper than the game, that sports is more than the score. That, at its best, it’s the stuff that gives us goose bumps.”

In February of 2025, Olson posted this on Facebook: Updating not just his life, his new wife, and his new son, but their newest challenge:

Who else wore No. 61 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

Chan Ho Park, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1994 to 2001, 2008):

Best known: When he arrived as a 20-year-old from Gongju, South Korea, many weren’t even sure how to pronounce his name. “Park Chan Ho,” said Dodgers broadcaster Ross Porter. “Ho Chan Park” was what the public address announcer said at Dodger Stadium when he became the first South Korean to play in the major leagues. He needed an interpreter, Don Yi, featured in the No. 94 post of this series, to help explain it all.

A 1994 profile by the New York Times shortly after his debut said “Mr. Park embodies the hopes of Korean-Americans throughout the country, about 500,000 of whom live in Southern California. … He has autographed more balls in English and Korean than anyone. No one in the American version of the game has ever been so scrutinized in Seoul.”

Before Park debuted on April. 8, 1994, the Dodgers scouted him during a multi-country high school tournament in Long Beach.

Park made two appearances in early ’94 and two more late in ’95 seasons before he was indoctrinated as a starter in April of ’96, then started full-time in ’97.

Park’s only All Star appearance was in 2001, a season after he went 18-10 with a 3.27 ERA and a career high 226 innings pitched at age 28.

Two memorable moments in Park’s Dodger career both came in 1999:

= April 23, 1999: In a game against the St. Louis Cardinals, Park’s third start of the season lasted two and two-thirds of an inning. He gave up 11 runs (six earned) while facing 22 batters. The reason: Fernando Tatis hit two grand slams off him in the third inning, the first and only time that feat has been accomplished in MLB history. The first one came with the first four hitters of the inning. Somewhere in there, Dodgers manager Davey Johnson was ejected by home plate umpire Greg Bonin. When Tatis came around to hit again, with two out, he hit another grand slam, leading to Park to be removed.

= June 5, 1999: The Dodgers and Angels were practically unidentifiable for this nationally televised Saturday afternoon interleague game. The Dodgers were in a dark blue top for the first time, as promoted by new team owner Fox, a large leap from from their traditional white home jersey. The Angels of Anaheim had the periwinkle pin stripes. Yuck, and yuck. Park started for the Dodgers was already trailing 4-0 after he gave up a grand slam to the Angels’ Matt Walbeck. In the fourth inning, Park, batting for himself in the NL park, laid down a sacrifice bunt. Angels pitcher Tim Belcher fielded it and put a tag on Park, who though it wasn’t necessary. The two pitchers had some words, and then Park unleashed a leaping spin kick on Belcher, emptying the benches as massive Angels first baseman Mo Vaughn stood by and watched in amazement. Park was ejected. Fans were already starting to call the new Dodgers jerseys “Karate Kick Blue.”

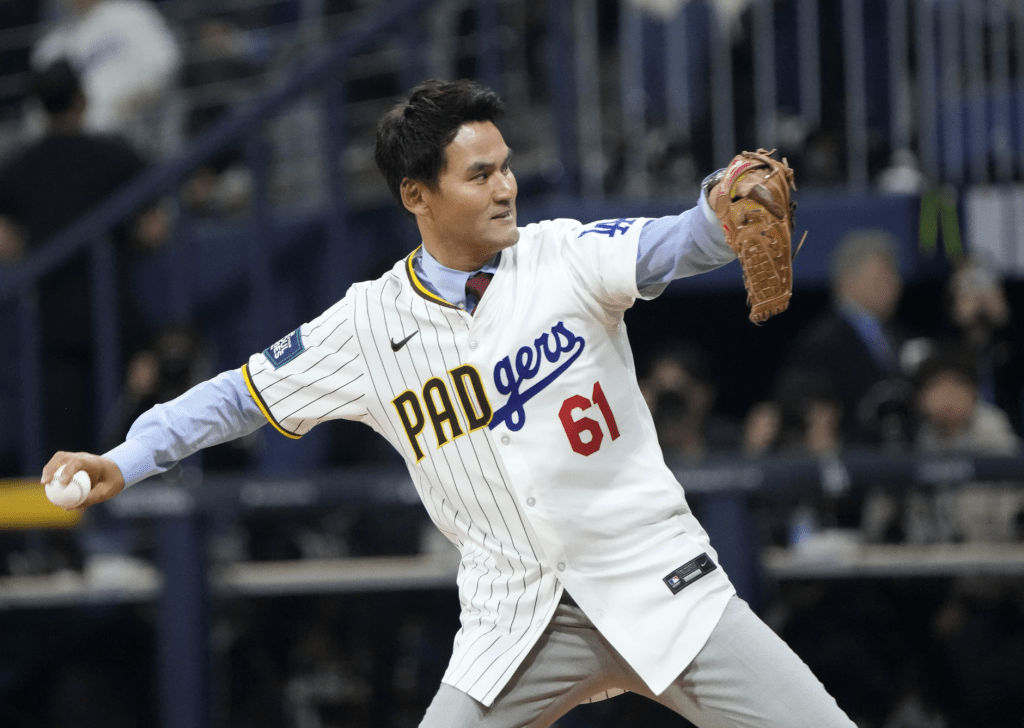

When the Dodgers and San Diego Padres started the 2024 season in South Korea, Park threw out the ceremonial first pitch, wearing a jersey half for the Dodgers and half for the Padres, where he pitched in 2005 and ’06). The New York Times headline this time called him “The Godfather of Seoul.”

Not well known: Park said he wanted 61 because it the was opposite of No. 16 worn by then Dodgers pitching coach Ron Perranowski. He ended up wearing that No. 61 for 17 MLB seasons, including nine with the Dodgers.

And then there’s this:

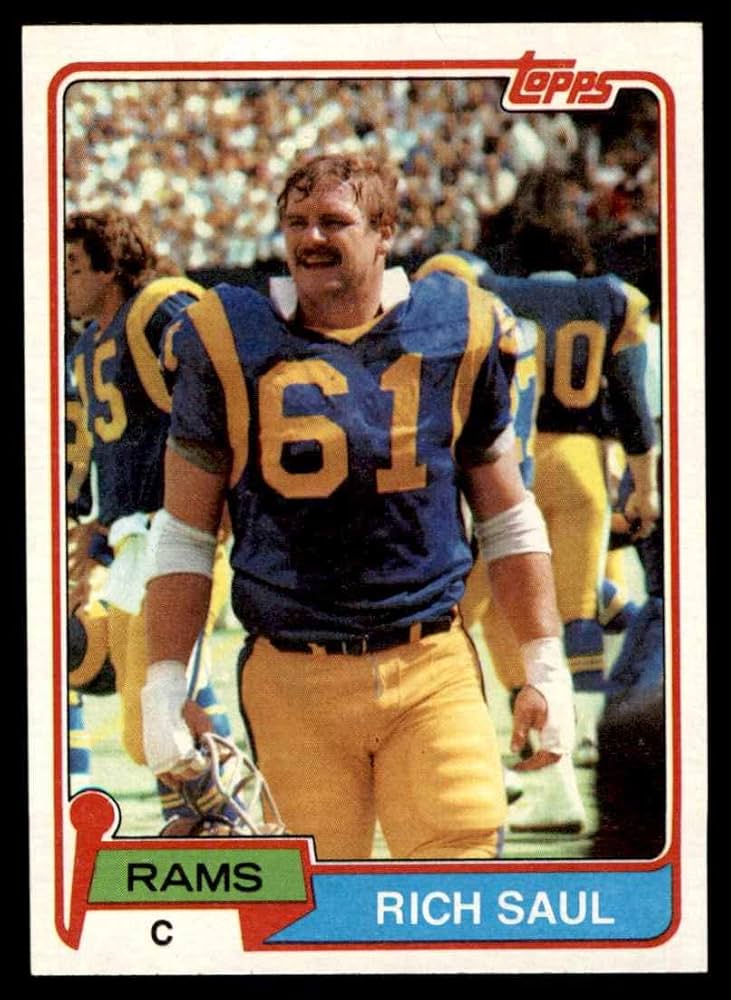

Rich Saul, Los Angeles Rams offensive lineman (1970 to 1981):

Best known: The 6-foot-3, 240-pounder out of Michigan State started 105 out of the 106 games at center from 1975 through the ’81 season, including six straight Pro Bowls and the 1980 Super Bowl, only after he spent his five seasons primarily as the long snapper. Saul died from leukemia at age 64 in 2012.

Not well remembered: His Rams teammates nicknamed him “Supe” — as in super — because he could play just about any position on the line and he “came out sounding like a superhero when he’d recount a story” about himself. It is noted that Saul, as a team captain, correctly called the coin flip on Jan. 20, 1980, and years after the 31-19 loss to the Pittsburgh Steelers in Super Bowl XIV. Saul would joke that at least the Rams won the coin toss that day.

Josh Beckett, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2012-14):

Best known: At mid-season 2012, the Boston Red Sox forced Beckett to be part of a package in a deal with the Dodgers, who were trying to secure first baseman Adrian Gonzalez but ending up taking a lot of extra payroll in the process. Beckett, a three-time AL All-Star at the time, netted just an 8-14 record in 35 starting assignments for the Dodgers, and it cost them more than $45 million total.

Not well remembered: The 34-year-old, who had been through several surgeries to repair thoracic outlet syndrome, fashioned a no-hitter at Philadelphia in May, ’14, in what would be his final season for the Dodgers.

Bill Fisk, USC football offensive guard (1962 to 1964):

Best known: An All-American out of San Gabriel High who was part of John McKay’s 1962 Trojan national title team, Fisk’s most indelible mark was for the 39 years he put in as the coach and teacher at Mt. San Antonio College. As the Mounties’ head football coach for 18 seasons (1987 to 2004), he had a record of 126-64-2, including 12-0 in 1997 and a JC national championship. His teams played in nine bowl games and Fisk saw more than 450 players receive scholarships to four-year universities. Even a handful more make it to the NFL. Fisk died in 2019 of cancer at age 75 two years after he was inducted into the Mt. SAC Athletics Hall of Fame.

Not well remembered: Fisk’s father, Bill, also played at USC (1937-39), playing in two Rose Bowls and part of the Trojans’ 1939 national title game. He then went to play professionally, including with the AAFL’s Los Angeles Dons.

Have you heard this story?

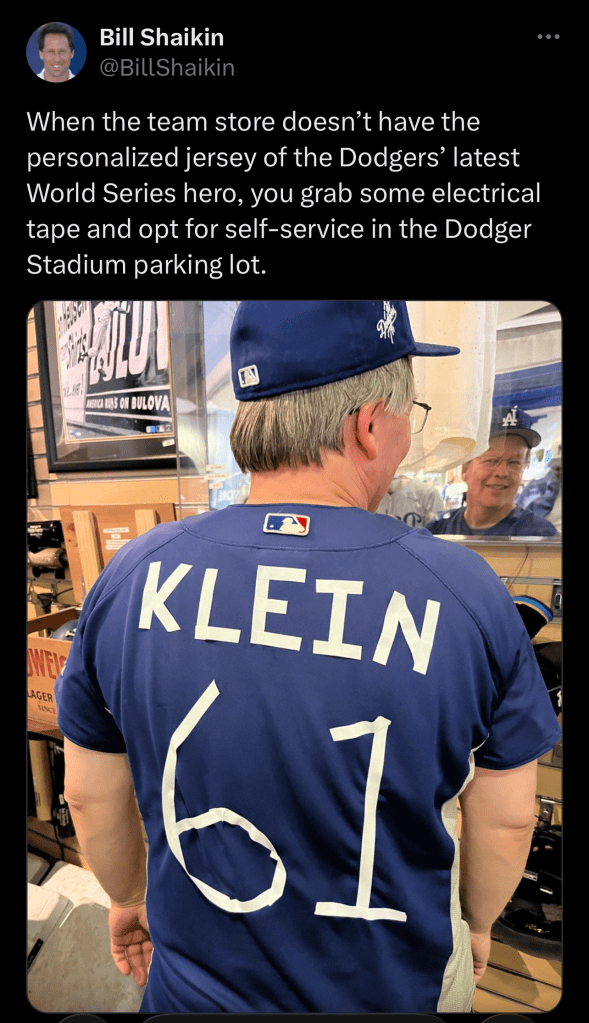

Will Klein, Los Angeles Dodgers relief pitcher (2025 to present):

Perhaps the final player added to the Dodgers’ 2025 World Series roster, a case can be made that without the four shutout innings William Boone Klein pitched during a 6-5, 18-inning Game 3 victory — 72 pitches, 15 batters faced, one hit, two walks, five strikeouts, and earning the victory as the 10th pitcher the Dodgers used that night — the team would have folded up against the Toronto Blue Jays in five games. Now, all the Dodgers have to do is create a jersey in his honor.

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 61: Jake Olson”