This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 22:

= Clayton Kershaw, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Elgin Baylor, Los Angeles Lakers

= Lynn Swann, USC football

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 22:

= Bo Jackson, California Angels

= Hugh McElhenny: L.A. Washington High football; Compton College football

= Brett Butler, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Bill Buckner, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Dick Bass, Los Angeles Rams

= Raymond Lewis, Verbum Dei High basketball

= Raymond Townsend: UCLA basketball

The most interesting story for No. 22:

= Ila Borders, Whittier Christian High baseball pitcher (1989 to 1993)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Downey, La Mirada, La Habra, Bellflower, Costa Mesa, Whittier, Santa Ana, Long Beach

A camera crew from CBS’ “60 Minutes” chased down Ila Borders, and she was bordering on a panic attack.

The 23-year-old had become national news of sorts. It was 1998. She was about to become the first pitcher to start a game in a men’s professional baseball league, with the Duluth-Superior Dukes of the independent Northern League.

Her instincts were to push back on anything at this m0ment that could distract from her mental preparation.

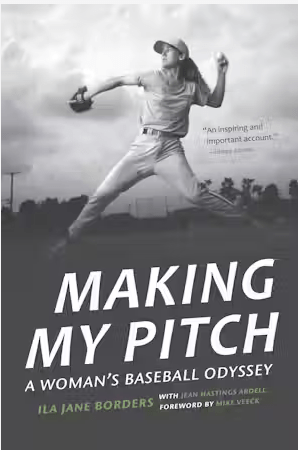

In the prologue of her 2017 book, “Making My Pitch: A Woman’s Baseball Odyssey,” Borders explained how she had to retreat to the women’s restroom at the ballpark, jump into a stall and put her feet up so no one could detect she was there.

“I’m an athlete here to win,” she wrote. “Now get the hell out of my face. Would you tell a guy to smile? Growing up I heard about Don Drysdale, the Los Angeles Dodgers star right-hander of the 1950s and 1960s. I was crazy about Drysdale, who everyone said was the nicest guy around — except for the days he pitched. Then no one went near him. … I’ve been fighting for this since I was ten years old.”

By the time Mike Wallace had the chance to sit down with Borders, her family, friends, managers and teammates to do the story, Borders had a chance to explain.

“I’ve always had this fierce spirit to do what I want to do,” she said.

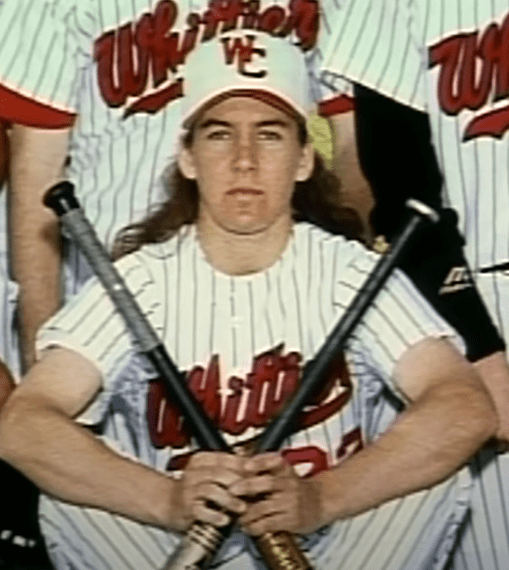

It want as far back to when she wore No. 22 for Whittier Christian High School in La Habra. Right about the time the movie “A League Of Their Own” had come out. There had been a template for women playing pro baseball, and Borders wanted in.

The background

By the time Ila Borders finished her first season pitching for the Whittier Christian High freshman team, posting a 5-1 record and 3.05 ERA was good enough for a call-up to the varsity team to help them prepare for a run the CIF playoffs, the concept that girl could succeed on a level of baseball higher than Little League and pizza parties was starting to become more clear.

It wasn’t as much a novelty no matter how others may have framed it.

The summer before her first year at the parochial high school, Phil Borders faked his daughter’s birth certificate so the two of them could play together in semi-pro adult Sunday hardball leagues. It allowed Ila to get acclimated to 60-foot, 6-inch mound-to-home distance, and integrate with more mature male players, gaining confidence and measuring up her abilities.

Phil Borders pitched in the Dodgers’ farm system for awhile. Don Sutton taught him how to throw a one-finger curveball. Phil taught it to Ila. She adjusted the grip into an effective screwball, which that curved away from right-handed hitters.

Born in Downey, Ila Borders shied away from following many of her friends to local La Mirada High. The public-school CIF rules weren’t stacked against her even getting a chance to play on a boys’ team. The Title IX standards were still a bit murky. She would most likely be pointed toward the softball field, and she wanted none of that.

As a high school sophomore, Borders posted a 5-2 for the Heralds with a 2.07 ERA. She threw a one-hitter and led the team in innings pitched. At one point, she was named Cal Hi Sports Athlete of the Week.

As a junior, on a team that went 4-11, she posted a 3.25 ERA and won three of their four games (against four losses). She was now throwing 85 mph fastballs.

“I remember the first time she came in,” said Whittier Christian coach Steve Randall before her senior season. “She said she wasn’t a girl try to make a point by playing the boys. She said she loved the game and was here to play.”

Borders added to that in a story posted in the L.A. Times’ high school section: “I’ll do anything to get on a college team or the major leagues. It really doesn’t matter who you are or what you are. I hope I can find some people who are willing to give me a chance. I don’t care about being the first woman to play in the major leagues. I just want to make it. … I’m not out here for show.”

In 1992, the movie “A League of Their Own” had come out. It showed what life, and challenges, there were for women playing in a professional league created during World War II. Borders identified with the grit and determination of Geena Davis’ lead character, Dottie Hinson.

By the time her high school career ended, Borders had a 16-7 record over 147 innings, striking out 165 and posting an 2.31 ERA. She was her team MVP two seasons in a row.

Now, several colleges were interested.

This wasn’t so much uncharted territory — a few other women were walk-ons at various college baseball teams in the late ‘80s already. But she would be the first to actually be given a scholarship — partial, as it turned out — and she settled on nearby Southern California College, an private Christian NAIA school in Costa Mesa later renamed Vanguard University of Southern California.

The day came — Feb. 15, 1994 — when the 5-foot-9 and 140 pound Borders had her first outing for any woman in NCAA or NAIA baseball history. She went the distance, throwing 104 pitches, in a 12-1 victory over Claremont-Mudd, striking out two, walking three and taking a shutout into the eighth. Wearning No. 25, she became the first woman to get a win in a men’s college baseball game.

The Washington Post covered it, as well as Sports Illustrated, The Sporting News, CNN, ESPN, Fox Sports and a TV crew from Japan. She said as a scholarship athlete she felt obliged to do as many interviews as needed and help the school.

“I didn’t sleep last night, not at all,” Borders said. “I went out there and I was shaking. I wanted to hurry up and get out there and go pitch. It wasn’t necessarily a fear of getting hit. I just wanted to pitch.”

Borders figured that she did 73 interviews over the next three days, including appearances on “Good Morning America” and “The Tonight Show with Jay Leno.”

During those interviews, she retold stories about how as an 8 year old in 1983 she was inspired to play baseball after seeing the Dodgers’ Dusty Baker hit a home run at Dodger Stadium.

She had been pitching since she was 10 years old in La Mirada Little League. At age 12, a local TV crew from KABC-Channel 7 with reporter Rick Lozano came out for an interview after she threw two perfect games and three no-hitters. She struck out 18 in the six-inning game the crew captured. She was also hitting .500 with a league-best eight homers.

But going back to when she was at Whittier Christian Middle School as a 13-year-old, Borders said she knew she was a “closeted gay girl in a Christian school who lived to play baseball,” and, on top of trying to fit into baseball, she was trying to fit into life.

There were coaching changes at Southern California College, and new ideas on whether she was better as a starter or reliever. Border was also going through a relationship breakup.

The confusion led her to decide she’d be better off playing her senior season at nearby Whittier College. Still wearing No.25, Borders posted a 4-5 record with a 5.22 ERA over 81 innings. It wasn’t the stuff that would draw attention from scouts looking for talent in the 1997 MLB Draft. There were rumors that the local Anaheim Angels would be willing to use a late-round pick on her. They didn’t.

She had an agent, Barry Moss, and they found out the Northern League, filled with teams and talent not affiliated with any MLB clubs, was ready for her. More specific, the famous St. Paul Saints and owner Mike Veeck, who valued his family legacy of going outside the lines to provide fans with something different on a baseball field.

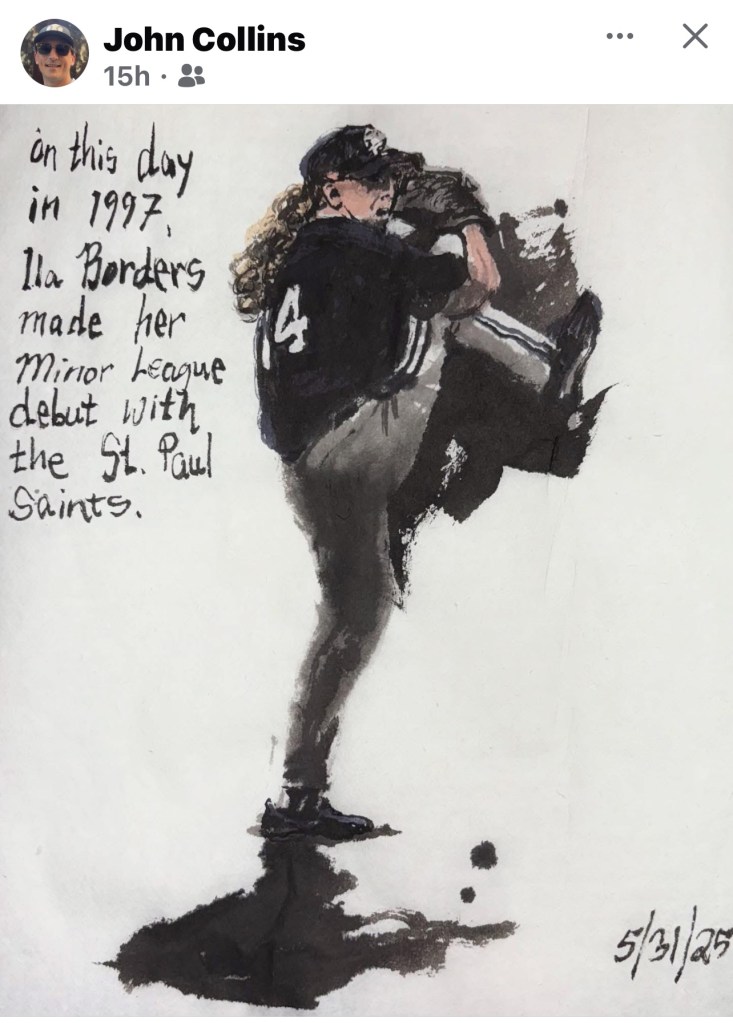

The Saints invited her to training camp, she pitched in a couple pre-season games and made the last roster spot. In her regular-season debut — May 31, 1997 — she entered in the sixth inning and faced three Sioux Falls batters. Her first pitch hit the first batter. She committed a balk, had a throwing error and didn’t record an out, giving up three earned runs.

The next day, she pitched a scoreless eighth inning against the same team, striking out three.

That made her the first female to pitch in a men’s pro league game since some had done it in the Negro Leagues.

Wearing No. 14, Borders pitched only seven games for the Saints in their first 22 games — a 0-0 record and 7.50 ERA –before she was traded to Duluth-Superior, wearing No. 3. Later that season, she picked up her first professional victory and had a 1.97 ERA.

She returned to the Dukes for the 1998 season, pitching from the bullpen at first. On Thursday, July 7, 1998, she was set to make a start. The media was geared up for it.

While she took the loss in a 8–3 home defeat against the Sioux Falls Canaries, the box score showed: Five IP, 3 ER, 5 H, 2 BBs, 2 Ks. Fourteen days later, she became one of the first female pitchers to record a win in pro men’s baseball, a 3–1 home victory against the same Sioux Falls squad.

A baseball from the game and the line-up cards were donated to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. Her line: Six IP, 3 H, 2 BB, 2 Ks, starting a streak of 12 scoreless innings. Her season totals were a 1–4 record, 44 innings, 8.66 ERA, 65 hits, 14 walks, 14 strikeouts.

After four seasons of independent-league baseball — 52 games for four teams, a 2-4 record with a 6.75 ERA to show for it — the 26-year-old retired midway through the 2000 season. She was with the Western League’s Zion Pioneerzz at the time, gave up five hits and three runs in a 10-6 loss to the Feather River Mudcats and finished that season with a 9.35 ERA over 8 2/3 innings.

Said Manager Mike Littlewood: “Ila was one of the most courageous people I’ve ever met or seen play the game.”

Borders summed it up: “I’ll look back and say I did something nobody ever did. I’m proud of that. I wasn’t out to prove women’s rights or anything. I love baseball. Ask a guy if he’s doing it to prove men’s rights. He’ll say he’s doing it because he loves the game.”

The year, the Cincinnati Reds were the only ones who said they were interested perhaps in inviting her to spring training. They decided it would be too chaotic.

What would be the next challenge?

When Borders decided her pitching days were done, Borders recalled how the Costa Mesa Fire Department members would come to watch her play in college, and “that has a profound affect on me,” she would write in her book. “Now I wanted to be that firefighter.”

And that became her new identity.

In 2001, she enrolled in Santa Ana College and got a degree in Fire Technology. The Long Beach Fire Department hired her in 2004. After a time in Arizona, she went to the Portland, Oregon, area to work as a fire academy instructor, getting a masters in public administration.

Another challenge came into her life: As she was staringto compile an autobiography in 2007, her partner was killed by a drunk driver in 2008. Borders stopped the project.

“I don’t remember conversations, or really anything, for six years,” Borders said.

With the help of Jean Ardell, the book was finished in 2017, and it is something she continues to lean on during speaking engagements, especially to high school classrooms.

In “Making My Pitch,” Mike Veeck wrote that when he first met Borders, he told her: “Ila, we are about to embark on a great adventure. It will be fun. It will be all that we both could hope for. But it’ll have its moments … You will be castigated, ridiculed, and called ‘a promotion,’ even though the Saints are already sold out for the season.”

Borders’ replay: “Mr. Veeck, I know exactly what we’re in for. I have been cursed, spat upon, beaned, and hit with all manner of missiles. I’m not afraid. I know what we’re up against. Do you?”

Even as she has done in this Chapter 1 excerpt, Borders tells kids today about her difficult childhood in Little League, fighting off depression while creating a work ethic to persist through all doubts. She could explain how many teammates resented her and the attention she got. She could relate to them how, as a girl, it wasn’t unusual for the boys pitchers she faced to hit her with a pitch. Over and over. All 11 times she came to bat in college, she was hit by the pitch. She had beer thrown at her.

“If I had to sum up my [pro baseball career] in one word, it would be stress,” Borders said in 2017. “I was having fun and I also loved the game. But then there was so much stress, and I remember a lot of that too.

“If it were just me pitching out there, it would have been fine. But because everyone was [weighing] in saying if I mess up, I’m messing of for women … Oh my gosh, I thought, I can’t mess this up. I’ve always been fine failing on my own and owning it. But then failing for everybody, when they are not going to recover, that takes on a whole different meaning.”

In 2026, the new Women’s Pro Baseball League is scheduled to launch, and Borders has done all she can to support it.

She has the knowledge that the Baseball Hall of Fame, which has several pieces of her playing-days equipment, includes her in the game’s history. In a piece posted about the history of women in baseball, the Hall story starts: “Women have been playing baseball almost as long as men have. Their long connection with the game began in the 1860s and has continued through the efforts of individual pioneers like Amanda Clement, Jackie Mitchell, Toni Stone, Maria Pepe, and Ila Borders.”

“There’s so many woman out there who just want to play baseball,” says Borders, who has also been involved in the MLB USA Women’s Trailblazing series, mentoring girls in the 16-year-old range. The MLB.com website posted a tribute to her during Women’s History Month in 2024. The Hall of Fame also posted a story chronicling her four-year independent league career. She has a bio posted on the Baseball-Reference.com site.

In the 2022 book, “Baseball Rebels: The Players, People and Social Movements That Shook Up the Game and Changed America” by Peter Dreier and Robert Elias, Borders’ story takes up seven pages. It puts her in the same company as Jackie Robinson, Larry Doby, Curt Flood, Helen Callagan and Pam Postema.

Borders’ story is also secured and curated by the Pasadena-based Baseball Reliquary, whose voters inducted into their Shrine of the Eternals in 2003 with Jim Abbott and Marvin Miller. Borders perfectly fits the mission of the Reliquary, created in 1996 to celebrate the sport’s rebels, mavericks, eccentrics, outcasts and oddities.

Borders’ connection to Whittier College is now also a connection to the Baseball Reliquary, which, in 2015, became the organization’s home base, housing volumes of reference material as well as it’s quirky collection of artifacts — thinks like hair curlers that belonged to Dock Ellis, a jockstrap worn by Eddie Gaedel and baseballs signed by Mother Theresa.

Another perfect circle-of-life moment for Borders.

“Baseball has so many wonderful relationships between the history of baseball and culture, politics and gender issues,” Cannon, who died in 2020, once said. “I try to draw parallels between how you can view what was going on with baseball and the society at large.”

As former minor-leaguer and movie producer Ron Shelton has said: “Baseball is often called the game of statistics, but the Reliquary is more about remembering the magic than the numbers.”

Like the magic of Ila Borders’ career in the game and her impact left on it.

Who else wore No. 22 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

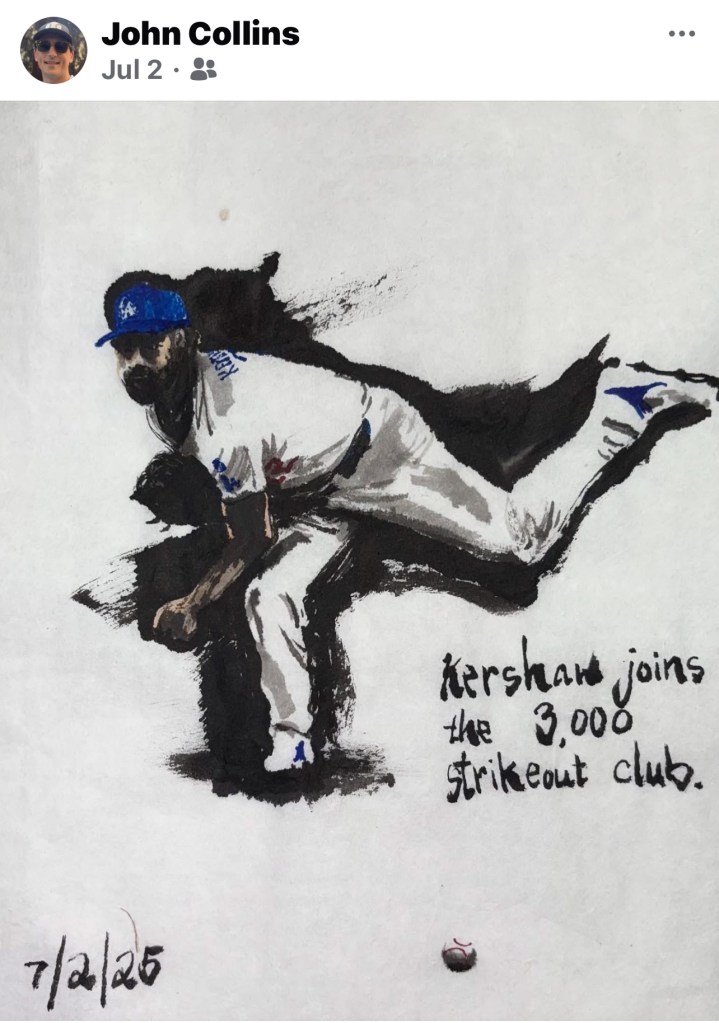

Clayton Kershaw, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2008 to 2025):

He wore No. 54 in his MLB debut on May 25, 2008 just a few months past his 20th birthday.

Six innings on a Sunday afternoon against St. Louis striking out seven and giving up just two earned runs got him the win. His first strikeout victim: Skip Shumacher.

The Dodgers knew Clayton Kershaw would stick, so teammate Mike Sweeney, who appeared in the game as a pinch hitter, saw the writing on the wall. Kershaw had wanted No. 22, because he grew up in Dallas idolizing Texas Rangers first baseman Will Clark. Sweeney, in his 14th and final Major League season and his second with the Dodgers, had been in possession of No. 22 and told the Los Angeles Times this giving to Kershaw and taking himself down a notch to 21 was a no-brainer: “ (He is) going to be in this uniform for a long, long time. It’s something important to do from an organizational standpoint.”

Take the number adventure further, and there’s actually a rookie baseball card issued for him wearing No. 46 from a spring training camp.

Most of what we need to know about the future Hall of Famer has been explained in detail in the 2024 book, “The Last of His Kind: Clayton Kershaw and the Burden of Greatness” by Andy McCullough. Among the interesting things in the book: a) Kershaw vowed to get to the big leagues before his 21st birthday. He beat that by 298 days; b) During Kershaw’s 2014 no-hitter at Dodger Stadium against Colorado, the Rockies’ Charlie Culberson made the second out of the ninth inning with a fly ball to right field. “If you watch the tape, it’s the only two-handed catch of Yasiel Puig’s career,” said catcher A.J. Ellis; c) Kershaw aligned himself with Sketchers after Under Armor stopped making his cleats in 2018. He was never aware that the brand was not considered hip. “They’re super generous with Kershaw’s Challenge,” he says. McCullough adds: “That was how he became the face of septuagenarian footwear”; and d) Remember Kershaw’s first start of the 2022 season: Seven perfect innings pitched at Minnesota. In the press, Kershaw said he agreed with manager Dave Roberts’ decision to take him out — as Roberts did with other pitchers in recent history. Kershaw had a short springing training because of the labor issues. It was 38 degrees at Target Field. Ellis later yelled at him for not trying to stay in the game. “I probably regret it now,” Kershaw says in the book to McCullough. “I think throwing a perfect game would have been cool. Doc, he wanted to take me out. Mark (Prior, the pitching coach) wanted to take me out so bad. I could really do what I usually do and make it super hard for them and stress them out. Or I just take it. So I just took this one. Looking back, I regret it. I should have at least tried.”

The three-time Cy Young winner, 10-time NL All Star, winner of five ERA titles and an NL MVP who reached 3,000 career strikeouts in July of 2025 and whose ERA or 2.53 is the lowest of any pitcher in the modern era with significant innings fits into team as explained in Jon Weisman 2018 book, “Brothers in Arms: Koufax, Kershaw and the Dodgers Extraordinary Pitching Tradition.” Kershaw had a final regular season of 11-2 in 23 starts, to finish 223-96, punctuated by marks of 21-5 (in ’11), 21-3 (’14), 18-4 (’17) and 16-5 (’19), plus a combined 25-8 in ’22 and ’23. It doesn’t offset a 13-13 mark with a 4.49 era in 32 starts during the post season. He is 3-6 in seven NL Championship Series. On Oct. 7, 2023 in NLDS Game 1 at Dodger Stadium against Arizona, he gave up six hits with eight batters faced and six earned runs in one-third an inning. His ERA was 162.0 for that series. The top-seeded Dodgers were swept away. Maybe Kershaw has time to remedy that. Maybe not.

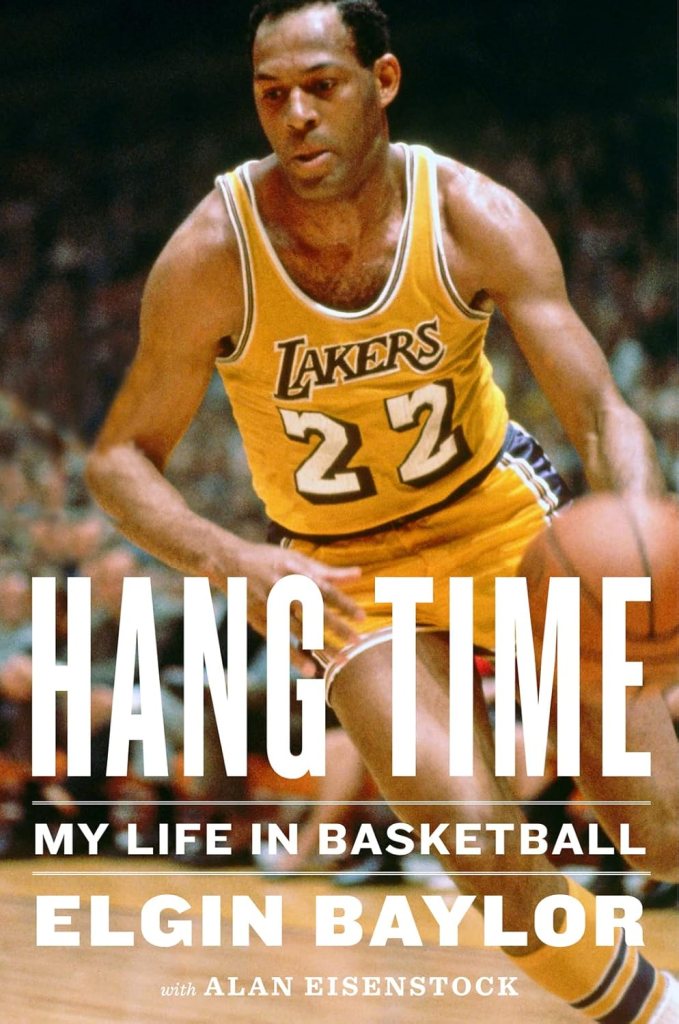

Elgin Baylor, Los Angeles Lakers forward (1960-61 to 1971-72):

The rare Lakers legend who never got to experience a championship, his name interestingly came up when the Lakers won the first-ever (last annual?) NBA In-Season Tournament in 2023. The ABC telecast pointed out the uniqueness of Anthony Davis’ ability to post 41 points, 20 rebounds, five assists and four blocks. The only Lakers who had a 40/20/5 game in franchise history — Baylor and Wilt Chamberlain. And Baylor did it four times in a row in 1961. In the Lakers’ first season in Los Angeles, Baylor averaged 34.8 points, 19.8 rebounds, and 5.1 assists. There’s also the fact that a couple months into their new L.A. home — on November 15, 1960 — Baylor established a new NBA scoring record when he hit 71 points to go along with 25 rebounds in a win over the New York Knicks. Only three players have ever eclipsed this mark with Chamberlain doing so five times, Kobe Bryant’s 81-point game in 2006, and David Thompson scoring 73 in 1978.

Minneapolis drafted him first overall in 1958, four years after its last championship, and he retired early in the 1971-72 campaign, famously one game before the start of the 33-game winning streak. He has a ring from that 1972 team but appeared in only nine games that season. Between those two bookends, however, Baylor was magical at 6-foot-5, averaging more than 20 points and 10 rebounds in 11 different seasons. In 1961, he averaged 19.8 rebounds per game. Baylor, who received a statue outside of Staples Center in 2018, remains the Lakers’ career leader in rebounds with 11,463. He twice set the NBA record for points in a game, first at 64 and then with 71. His 61 points in Game 5 of the 1962 Finals against Boston remain a Finals record. It’s also the incredible feat that during the 1961-62 season, Baylor played only 48 games — all on weekends, all without practicing — and somehow averaged 38 points, 19 rebounds and five assists a game. A U.S. Army Reservist at the time, Baylor lived in a barracks in the state of Washington, leaving only whenever they gave him a weekend pass, then flying coach on flights with multiple connections to meet the Lakers wherever they happened to be playing. That was his life for five months.

Three books seem to circle the wagons best on his career for the full treatment: In 2017, there was “Elgin Baylor: The Man Who Changed Basketball” by Bijan C. Bayne, with roots in Washington, D.C., where Baylor grew up; Baylor’s own autobiography a later later called “Hang Time: My Life in Basketball,” which gets far into his time at the Los Angeles Clippers clumsy general manager; and “Above the Rim: How Elgin Baylor Changed Basketball,” from 2001, a children’s book by Jen Bryant with beautiful illustrations by Frank Morrison.

Baylor trivia: In Game 4 of the 1959 NBA Finals, he wore No. 34 for the Minneapolis Lakers. Just in the first half.

Bill Buckner, Los Angeles Dodgers first baseman/outfielder (1969 to 1976):

His one and only at bat as a 19-year-old came during a September call-up as he was also attending USC. He wore No. 38 on that day. Traded to the Chicago Cubs for Rick Monday after the 1976 season, Buckner won the 1980 NL batting title (.324) and would also wear No. 6 for the California Angels in 1987 and ’88 following his time with the Boston Red Sox. If not for his ability to move to left field, Buckner could have been the Dodgers’ longtime first baseman in the 1970s. Blame Steve Garvey’s throwing arm. But it wouldn’t have allowed him on an April night in 1974 to try to chase down Henry Aaron’s 715th home run ball in Atlanta. We still see him trying to climb the left-field fence.

Brett Butler, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (1991 to 1994, 1996 to 1997):

The 1996 winner of the Lou Gehrig Memorial Award (one who best exemplifies the spirit and character of the late Yankees first baseman) and the Branch Rickey Award (for community service) reflects the way he was diagnosed with throat cancer in mid-season that year, received treatment and returned to the playing four months later. His first season with the Dodgers (he was born in L.A.) after the previous six with the rival Giants produced his one-and-only All-Star selection — he led the NL with 108 walks, 112 runs scored and 732 at bats in 161 games to go with a .296 average, 182 hits, and 28 steals and was seventh in NL MVP voting. The next season he led the NL with 24 sacrifice bunts to go with a .309 average. His 11 triples in ’92 and 10 in ’93 didn’t lead the NL, but his nine in ’94 did. He also wore No. 12 with the Dodgers for a brief time in 1995, after returning to L.A. from the New York Mets.

Lynn Swann, USC football receiver (1971 to 1973):

His All-American senior season saw him lead the NCAA with 37 receptions, 667 yards, six touchdowns and an 18.0 yard-per-reception average. In his career he also returned 49 punts for 599 yards (12.2 average) and two touchdowns, plus ran 26 times for 200 yards a 7.9 yards-per-gain average. “He has speed, soft hands, and grace,” said coach John McKay. He had 95 catches in his USC career for 1,562 yards (16.4 average) with 11 TDs. He was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame and the Senior Bowl Hall of Fame in 1993, the USC Athletic Hall of Fame in 2005 and the Rose Bowl Hall of Fame in 2013. He received the NCAA Silver Anniversary Award in 1999. His nine-year NFL career in Pittsburgh led to three Pro Bowls, four Super Bowl titles and a 2001 Pro Football Hall of Fame status. After 30 years as a sportscaster and a 2006 Republican nominee for Pennsylvania governor, Swann was named USC’s eighth athletic director in 2016.

Johnny Podres, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1958 to 1966):

A three-time NL All Star in L.A., Podres was the winning pitcher in the Los Angeles Dodgers’ first victory — 13-1 at San Francisco, a complete-game effort striking out 11. Podres started that season 4-0. Also wore No. 45 in Brooklyn from 1953 to 1957.

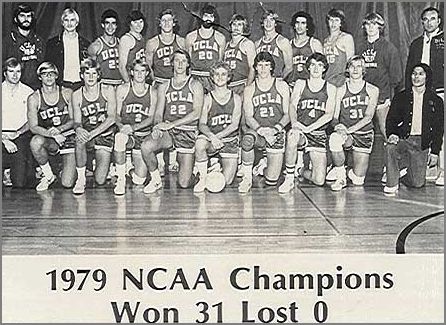

Singin Smith, UCLA volleyball setter (1976 to 1979): Before his fame on the beach volleyball circuit, the 6-foot-3 Christopher St. John Smith played on two national championships for the Bruins as freshman and a senior (the team was 31-0 and beat USC 3-1 in the title). He got to another final as a junior. A consensus All-American as a junior and senior, and NCAA Championship Most Outstanding Player of ’79, he was inducted into the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 1991. His No. 22 was retired by the school. In the summer he was out of UCLA, the Santa Monica native teamed with UCLA alum Jim Menges to win the Manhattan Open beach event — the first of six times — and launch his career as a beach legend with partners such as Karch Kiraly and Randy Stoklos. By the time he retired from the beach, he won 139 career tournaments.

David Eckstein, Anaheim Angels shortstop (2001 to 2004): The 5-foot-6, 160 pounder made his mark during the Angels’ 2002 title run by hitting three grand slams, including in back-to-back games against Toronto, the second of which was a walk-off that completed a sweep and ignite the team on winning 20 of their next 23 games. He also led the AL that season with sacrifice bunts (14) and being hit by a pitch (27), two categories he also topped in the league a year before as a rookie.

Walt Torrence, UCLA basketball guard (1956-57 to 1958-59): A three-year starter who became team captain, the 6-foot-3 foward led the team in rebounding all three seasons and had a team-best 21.5 points as well as a senior. He left the program third all-time in rebounds, second in scoring average and third in total points. Elected to the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 2009.

Wendell Tyler, UCLA football running back (1973 to 1976): The 5-foot-10 and 198 pounder out of Crenshaw High broke Kenny Washington’s long-held school record for rushing attempts in a single season as a junior in 1975 and, in doing so, also became the very first player in the Westwood school’s history ever to exceed 1,000 yards rushing for a season (1,388 as it turned out, with a 6.7 yards per carry average). In the followup 1976 Rose Bowl win over Ohio State, Tyler ran for 172 yards, including a 54-yard TD that sealed the win. Finishing as the school’s all-time leading rusher with 3,181 yards, Tyler was an inductee into the UCLA Athletics Hall of Fame in 2016, Tyler was picked by the Los Angeles Rams in the third round of the 1977 Draft, and he wore No. 26 as a running back there from 1977 to 1982.

Mel Farr Sr., UCLA football (1964 to 1966): Seventh in the 1966 Heisman voting after amassing 809 yards rushing and 10 TDs (teammate Gary Beban was fourth), Farr was a first-round draft pick by the Detroit Lions and inducted into the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 1988.

Tiger Williams, Los Angeles Kings left wing (1984-85 to 1987-88): The NHL career leader in penalty minutes never quite led the league in that category during his stay in L.A., but he did rack up a career high 358 minutes in 76 games during ’86-’87, after amassing 320 the previous season. On the website HockeyFights.com, Williams is listed as having 11 fights in ’84-’85, 16 in ’85-’86, 19 in ’86-87 and two in ’87-88. He had as many as 36 fights in ’77-’78. Not to be overlooked, he put up a hat trick in a March ’86 game against Montreal during a 6-4 loss to the Canadiens. When the Kings hosted the 2002 NHL All-Star game, the league held its first Celebrity Challenge event, and the home team all wore No. 22 in honor of Williams.

Have you heard this story:

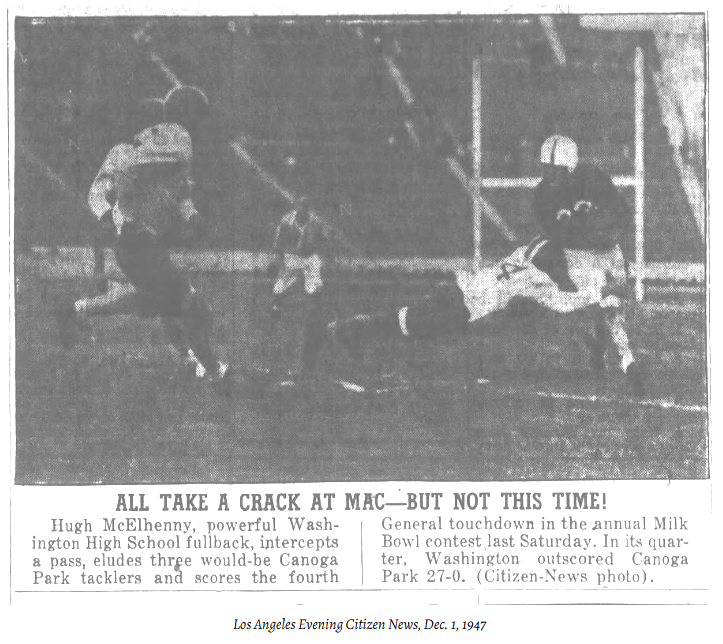

Hugh McElhenny, L.A. Washington High running back (1943), Compton College (1944):

Before his Pro Football Hall of Fame career, McElhenny was heralded as “the original five-star recruit” and a “once-in-a-generation prospect” when he was named 1947 L.A. City football player of the year, state champion in the high jump and long jump, and clocked as fast as 9.7 in the 100 yards and 14 seconds flat in the 120-yard hurdles.

McElhenny, a 6-foot-1 and 200 pounds, was “impossibly large for a running back at that time,” according to a New York Times profile. Wearing No. 22, McElhenny’s newsworthiness in football started in his senior season at Washington, after a broken collarbone wiped out his junior year and he focused on track as a sophomore. As a senior, “Hustlin’ Hugh”/”Hurricane Hugh” scored 18 touchdowns. Some wondered more if he would be a Olympic track star than do anything on a football field, because he made that look too easy. “Mostly,” the Los Angeles Times wrote, “he just outruns the opposition.” Back then, the city’s top 12 prep football teams participated in the Milk Bowl at the L.A. Coliseum, a daylong charity jamboree featuring six consecutive games, with a 25-minute running clock for each. Fans clamored for McElhenny’s Washington team to play in the finale — the best matchup, traditionally — and a reported crowd of 34,302 watched McElhenny score four touchdowns, return a punt 71 yards and intercept two passes in a pummeling of Canoga Park. He scored another four touchdowns two weeks later in an exhibition victory over Cathedral High.

“When I finished high school I could have gone to any university in the country,” McElhenny once said. It just depended on which one could provide the most incentives. It seemed most obvious he would stay to play football at USC, and he enrolled in a “extension diversion” program early with the idea he would be eligible as a freshman in 1948. But by mid-March, he withdrew from USC without much explanation.

McElhenny spent one season at 11-0 Compton College, rushed for 1,298 yards on 134 carries, once had a 105-yard kickoff return for a touchdown and won the Paul Williamson Award as the nation’s top junior college player. Compton then beat Duluth 48-14 at McElhenny scored twice in the Dec. 10 “Little Rose Bowl” in Pasadena. Los Angeles Mirror columnist Maxwell Stiles called the 19-year-old McElhenny “without a doubt the most important college football player on the Pacific Coast today.” Stiles added that the 19-year-old “is said to be allergic to textbooks and classrooms. … He maintained a C average at Washington High and he’s doing the same at Compton.”

After playing before large crowds at Gilmore Stadium and Wrigley Field, McElhenny diverted to the University of Washington in 1949 in a convoluted set of circumstances (again, putting off USC, UCLA, N0tre Dame, Nebraska, Navy and Alabama. In a game against USC, he ran a punt back for 100 yards for a TD. McElhenny became a two-time, record-breaking All-Pacific Coast Conference fullback. Wearing No. 39, McElhenny was a five-time All-Pro with the San Francisco 49ers during a 13-year NFL career where he was nicknamed “The King,” going into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1970.

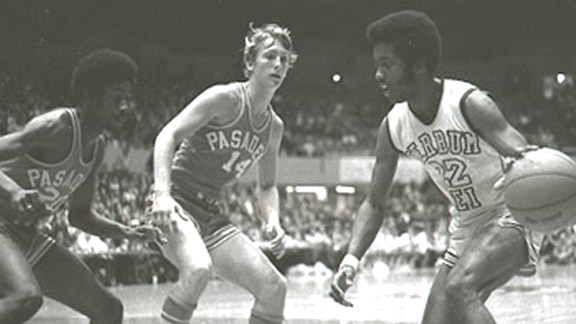

Raymond Lewis, Verbum High basketball (1968 to 1971):

In Sports Illustrated’s 1978 Pro Basketball Preview issue, a story was included with the headline: “A Legend Searching for His Past: Raymond Lewis was considered the greatest basketball talent in L.A., but he’s still waiting to play in his first NBA game.” It never happened. The “legend” part comes from Lewis leading his small parochial school to three CIF titles (they were a combined 84-4 often playing against schools with much larger enrollments) and the start of a local dynasty. He was a two-time CIF player of the year and averaged 24 points a game as a senior to become one of the most heralded players from Watts.

Despite several major college offers, and most likely joining Jerry Tarkanian at Long Beach State, Lewis was incentivized to go to to Cal State L.A. and average 38.9 points a game on the freshman team (unable to play varsity). As a sophomore (wearing No. 10), Lewis scored 32.9 a game, second in the NCAA, and once hit 53 in a double-OT 107-104 win over conference leader and No. 3-ranked Long Beach State and Tarkanian. “Raymond Lewis was one of the greatest players I’ve ever seen … nobody can change my mind about that,” said summer ball pioneer Sonny Vaccaro. “The difference between Raymond and some other high school standouts that became legends is he played against pros.”

In the ’73 NBA Draft, the 20-year-old went 18th overall to the Philadelphia 76ers. The rest is tough to explain. At 32 he was still playing pickup games in Long Beach thinking he could get an NBA team interested. “What Earl Manigault was to New York’s playground basketball scene, Raymond Lewis was to Los Angeles’ hoops culture,” was how one writer put it. A 2022 documentary, “Raymond Lewis: L.A. Legend” sums it best the life of a man who died in 2001 at age 48.

Gus Shaver, USC football quarterback/fullback (1929 and 1931):

After three seasons playing quarterback at Covina High and leading the Colts to the state title in 1925 and ’26 (as well as set the school’s pole vault record of 12-feet, 6-inches), Shaver was part of coach Howard Jones’ “Thundering Herd” that started with a 47-14 win over Pitt in the 1930 Rose Bowl to cap a 10-2 season. In ’31, as a consensus All-American, he led the team to a national title game. En route, he scored two touchdowns in the fourth quarter to lead the No. 1 Trojans past Notre Dame, 16-14, in South Bend, Ind., which led to an unheard of parade from L.A. City Hall to the USC campus when their train returned. That USC team defeated Tulane 21-12 in the Rose Bowl, as Shaver led the squad with 936 yards rushing.

Bo Jackson, California Angels outfielder/DH (1994):

He wore No. 16 during five amazing years with the Kansas City Royals — including in the 1988 All-Star Game at Anaheim Stadium, where he received the game’s MVP Award for an electrifying first-inning home run. In Jeff Pearlman’s book, “The Last Folk Hero: The Life and Myth of Bo Jackson,” a writer from the Orange Coast Daily Pilot is quoted: “There’s this beautiful moment in Southern California when you’re watching a baseball game and the air is perfect, the shadows are setting in, the light makes it look like a movie set. That’s the precise moment when Bo hit his home run. It was bigger than a baseball moment. It was artistic.” After his time with the NFL’s Los Angeles Raiders and he returned to the MLB, Jackson went to No. 8 during his hip-injury comeback with the Chicago White Sox in ‘93. He combined the two number and sported No. 22 when he played his final MLB season as a DH for the Angels, the team actually that drafted him in the 20th round in 1985 after his junior season at Auburn before he became the Heisman Trophy winner. Interestingly, the Angels had No. 34 was available — the number he wore with the Los Angeles Raiders from 1987 to 1990 — but he didn’t ask for it. With the Angels at age 31, he hit .279 with 13 homers and 43 RBIs in 75 games, with 43 of those as a left fielder (where he had three outfield assists), plus three games as a right fielder and nine as the DH). In his very first game, starting in left field, he threw out a runner at home trying to score on a Kirby Puckett double in the third inning. His best offensive game: 3-for-4 with a homer against Boston on July 20. The only reason he didn’t have more games or at bats: MLB went into a lockout in August of that season, a month short of the end, wiping out the post season. The Angels also went through three official manager that year, starting with Buck Rogers, having Bobby Knoop take over for two, and Marcel Lachmann finish. And with that, Jackson abandoned his desire to play any more.

John Cappeletti, Los Angeles Rams running back (1974 to 1978): The Rams took the Heisman Trophy winner from Penn State with the 11th overall pick in the first round and eventually made him a starter for three seasons from ’76 to ’78. He finished with 15 touchdowns rushing and three receiving for the Rams before heading to San Diego for his final four pro seasons. And if you’re up for a good cry, watch the movie or read the book “Something for Joey.“

Raymond Townsend, UCLA basketball guard (1974-75 to 1977-78): He had three coaches at UCLA — the final year of John Wooden and an NCAA title, two Pac-8 titles with Gene Bartow, and then another title with Gary Cunningham as a senior when he had a 14.7 points a game average. When Towsend was the No. 22 overall pick in the NBA draft by Golden State he had the distinction of becoming the first Filipino-American in the NBA.

Mudcat Grant, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1968):

As the two-time All Star bounced around in his 14-year career, from Cleveland to Minnesota, eventually to Montreal, St. Louis, Oakland and Pittsburgh, he had a stop with the Dodgers — traded by the Twins to L.A. with Zolio Versalles for pitchers Bob Miller and Ron Perranoski plus catcher John Roseboro. Grant went 6-4 with a 2.08 ERA in 37 games, including four starts, and recorded three saves. He also hit a two-run homer of the Cubs’ Bill Hands to give the Dodgers a 2-0 lead at Dodger Stadium in a game he’d eventually lose, 5-3. It was just two seasons after he led the AL with 21 wins and six shutouts during the 1965 season as his Twins lost to the Dodgers in a seven-game World Series. Grant was the first black pitcher to win 20 games in a season in the AL and the first black pitcher to win a World Series game for the AL. He had two complete-game wins over the Dodgers — an 8-2 win in Game 1 over Don Drysdale and a win in Game 6 where he also hit a three-run homer. The Dodgers lost Grant in the expansion draft to Montreal, and he was the Expos starter in their first ever game (giving up six hits and three runs in 1 1/3 inning of a game Montreal would win 11-10. Grant would move to L.A. and become a public speaker and community activist, writing a book in 2005 called “The Black Aces,” detailing the careers of those Black MLB players who had 20-win seasons as he once did. He died in L.A. in 2021 at age 85, eight years after he was enshrined in the Baseball Reliquary’s Shrine of the Eternals and then given a honorary doctorate of Humane Letters from Whitter College in 2016.

The Angel City FC “Player 22” Program: The National Women’s Soccer League team officially retired the jersey before their July 30, 2022 game against OL Reign to mark the start of “The Player 22 Program,” named in homage to franchise’s spring 2022 kickoff and the 22 players on the pitch in every match. It encourages fans to purchase specially designated merchandise from the team store where 10 percent of each sale goes toward a fund to help former NWSL players in a pursuit of a post-career venture in the sports industry. To help manage the application and selection process as well as oversee the distribution of funds, ACFC partnered with the California Community Foundation.

We also have:

Kenny Heitz, UCLA basketball guard (1966-67 to to 1968-69)

Tommy Curtis, UCLA basketball guard (1971-72 to 1973-74)

Raymond Townsend, UCLA basketball guard (1974-75 to 1977-78)

Ian Laperriere, Los Angeles Kings right wing (1995-96 to 2003-04)

Boog Powell, Los Angeles Dodgers first baseman (1977)

Dick Schofield, California Angels shortstop (1984 to 1989), Los Angeles Dodgers shortstop (1995). Also wore No. 30 in 1983, No. 17 from 1990 to 1992 and No. 9 from 1985 to ’86 for the Angels.

Anyone else worth nominating?

4 thoughts on “No. 22: Ila Borders”