This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 27:

= Mike Trout: Los Angeles Angels

= Vladimir Guerrero: Anaheim Angels/Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim

= Matt Kemp, Los Angeles Dodgers

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 27:

= Kevin Brown: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Theotis Brown: UCLA football

= Alec Martinez: Los Angeles Kings

= Jennie Finch: La Mirada High School softball

The most interesting story for No. 27:

Willie Crawford, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (1964 to 1975)

Southern California map pinpoints:

South Los Angeles, Dodger Stadium, Hollywood Hills

In the summer of 1964, the Los Angeles Dodgers could not afford to lose the talents and potential of Willie Crawford. Especially since he was right in their backyard.

Despite coming off a World Series championship, the franchise may have been pitching rich but it was offensive poor. Imagine a local high-school phenom as the future centerpiece of their lineup. Heck, if the rival San Francisco Giants had a sweet-spot of their order with Willie Mays and Willie McCovey, L.A. could dream about the potential if its own Willie Davis and Willie Crawford.

Of course, it was an awful lot to ask of a 17-year-old from South Central L.A.’s Fremont High.

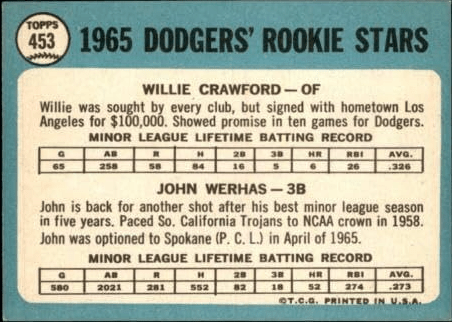

The catch was giving Crawford a $100,000 “bonus baby” status. It guaranteed him at least two seasons on the big-league roster, no matter how much learning was required to play at that MLB level.

It was somewhat of a crapshoot, based on “bonus baby” history, most often to the player’s determent. This would be the last year Major League Baseball allowed itself to continue this free-agent, Wild West signing frenzy and finally figure out how to implement a true draft.

The Dodgers couldn’t afford to let Crawford go elsewhere and were willing to take a shot, based on what they saw.

The motto of Fremont High is: “Find a path, or make one!” The school’s sports teams nickname is the Pathfinders.

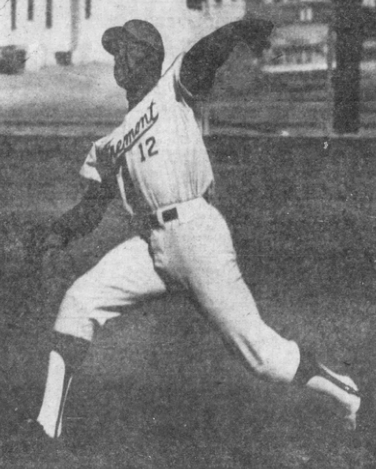

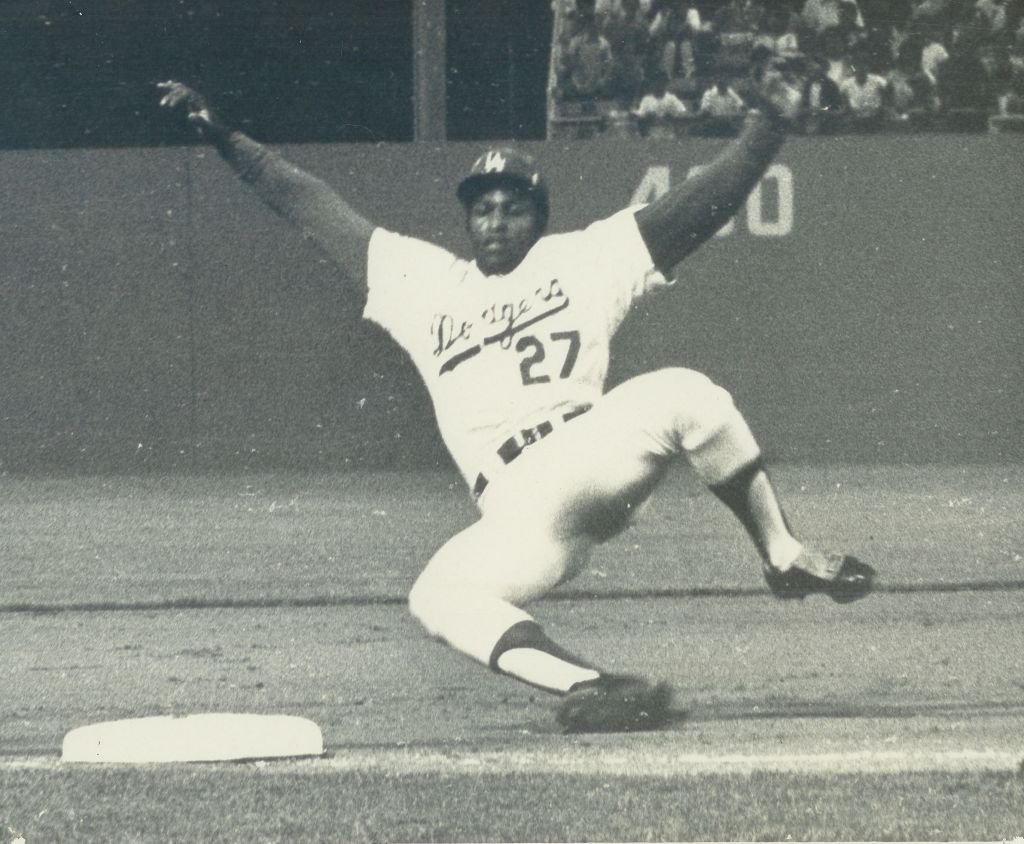

College recruiters beat a path to Crawford’s family home on 69th Street in L.A. long before his senior year at Fremont was over. Crawford gained attention as an All-City running back on the football team. On the track team, he clocked a 9.7 second 100-yard dash — or, it was 9.6 if you saw it on the back of his 1970 Topps baseball card, which also proclaimed he had a 21.2 second-mark in the 220, and twice cleared 25 feet in the long jump.

More to the Dodgers’ point, Crawford also hit .444 his senior year of baseball. Power, speed and a throwing arm. The whole five-tool package.

Dodgers scouting director Al Campanis’ report said of Crawford: “Thin waist, strong upper body, strong legs, unusual speed, graceful fielder, strong arm, good character (and ) hits with the power of Roberto Clemente and Tommy Davis at a similar age.” Campanis would know. He scouted and helped sign both for the Dodgers. The comparisons continued.

On the baseball fields of the high school on San Pedro Street between Florence and Manchester, “The Mont” had been creating a path to success under coach Phil Pote, who would go on to be one of the most heralded MLB scouts. His 1963 L.A. City championship team had future pro players Bob Watson, Bobby Tolan and Crawford. Brock Davis, another outfielder who went to Cal State L.A. and was signed by the Houston Colt 45s, also played with Crawford. The school had previously produced Hall of Famer Bobby Doerr, plus heralded manager Gene Mauch. It would later send Eric Davis, Chet Lemon, George Hendrick and Dan Ford to the MLB road.

This was one year before there would be the first official MLB draft, so Crawford’s pursuit was just following a slippery slope toward a large roll of the dice by teams, and players, as he was free to sign with whomever he wished.

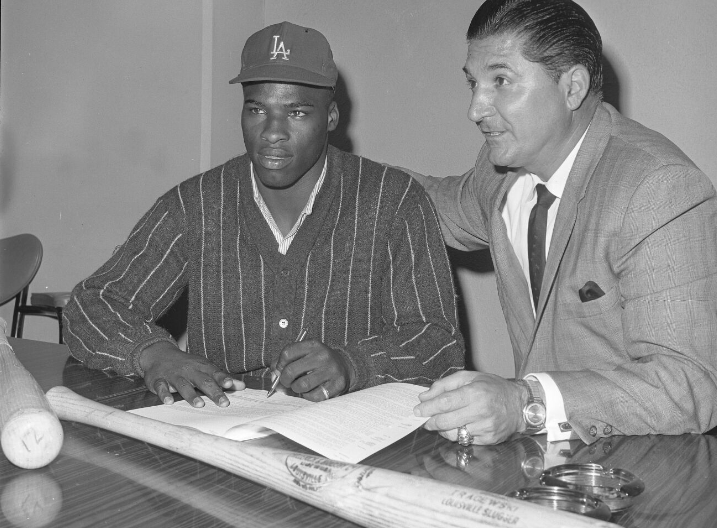

Two days after he graduated from high school, Crawford was sitting at his parents’ dining room table with Campanis, who was acting on what Dodgers scouts Tommy Lasorda and Kenny Meyers believed to be true — he was their guy. Sixteen of the 20 MLB teams were also making formal offers.

That included the Los Angeles Angels and owner Gene Autry, even though they had just paid 21-year-old outfielder Rick Reinhardt a record $205,000 bonus out of the University of Wisconsin and were about to give another $100,000 bonus to 18-year-old catcher Tom Egan from El Rancho High in Pico Riviera.

Then there was Kansas City Athletics’ owner Charlie Finley, who made a special trip to Crawford’s home to impress the family. Finley called Crawford “a Willie Mays with the speed of Willie Davis.” He gave the Crawford family an autographed photo of him to put on their wall.

Finley’s offer was a reported $200,000, plus the chance to start in center field right away for a team that would finish 1964 with a 57-105 record. The Dodgers were only offering half that, but the lure of a historic franchise that had moved to L.A. six years earlier and had already won two World Series titles. Crawford was also breaking new ground — no other African-American player right out of high school or college was even offered that large a signing bonus. Philadelphia signed Richie Allen for $70,000 in 1960. The Cleveland Indians gave Tommie Agee a $60,000 bonus in ’61.

Because Crawford said he wanted to stay on the West Coast, and he appreciated that Lasorda attended the funeral of his grandfather, the Dodgers got the signature on June 22, 1964.

The Dodgers were doing so knowing that they had to abide by the framework of the “Bonus Rule” — first implemented in 1947, then revived in 1952, as it declared that when a player received a large bonus that exceeded a certain amount, the signing team could send him to the minor leagues that season, but then had to keep him on the major league roster all of the following season.

In some ways, it tried to discourage bidding wars and punish a team that overspent. It often ended up punishing players who needed more time to adjust to pro ball and find their way in the minor leagues.

One of the first cautionary tales for this “Bonus Baby” rule was from Southern California.

In 1951, the Pittsburgh Pirates signed Narbornne High’s Paul Pettit, the “Wizard of Whiff” who, in one 12-inning high school game, struck out 27. The 18 year old was being compared to Cleveland’s Bob Feller. The Pirates gave him a reported $100,000 — a bonus that was matched or exceeded just six times in the “bonus baby” era between 1948 and 1965 — including Crawford’s signing.

Pettit, who also played for the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League, would injure his left pitching arm, try to come back as an outfielder, and realize he couldn’t live up to those expectations. He would coach various South Bay high schools and was an assistant principal at Hawthorne High in the late 1970s.

Bonus babies in the less-than-20-year-period of that rule included future Hall of Fames such as Sandy Koufax, Al Kaline, Harmon Killebrew, Catfish Hunter and Roberto Clemente. Those with Southern California ties: Dorsey High shortstop Billy Consolo (1953, Boston); St. Anthony High of Long Beach/USC/Loyola College second baseman Joe Amalfitano (1954, N.Y. Giants); Long Beach Wilson High catcher Jim Pagliaroni (1955, Boston); Fairfax High/USC outfielder Al Silvera (1955, Cincinnati); South Gate High pitcher and L.A. City Player of the Year Jim Derrington (1956, Chicago White Sox — the youngest pitcher ever to start an American League game at age 16); Mark Keppel High of Alhambra pitcher Mike McCormick (1956, N.Y. Giants); Compton High shortstop Bobby Henirich (1957, Cincinnati); Bell High/USC second baseman Buddy Pritchard (1957, Pittsburgh); and Long Beach Wilson High third baseman Bob Bailey (1962, Pittsburgh).

If Pettit was the first, Crawford would be one of the last. And there were far more stories told about those who didn’t pan out than those who succeeded.

A case in point: In a 1965 Sports Illustrated story previewing the Dodgers’ upcoming season, which included pointing out that Crawford was expected to be a noted contributor, there was also this point of optimism:

Virtually certain to stay with the Dodgers is Tommy Dean, a $60,000 bonus baby from Iuka, Miss., one of the most exciting young shortstops to come into the National League in years. “No player has ever reminded me so much of Pee Wee Reese at the same age,” says Bavasi. “And no one is going to get him away from us in any draft.”

Dean didn’t make his MLB debut with the Dodgers until September of 1967. Back at Triple A for another full season, Dean was made available in the 1969 expansion draft, and San Diego took possession of him for what would be his final three MLB seasons before he was done at age 25 with a .180 career batting average.

In July of ’64, when Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley returned from a vacation hunting polar bears in Norway, he said he knew about the signing and told the L.A. Times: “I don’t resent the bonus to Crawford. Clubs with less patronage cannot afford to compete with teams like the Yankees and Dodgers.” O’Malley said he hoped “some intelligent agreement on the bonus rule may be reached” sooner than later to avoid this kind of high-risk exercise perpetuating.

Looking back on this, had the MLB draft been in place one year earlier than it was in 1965, Finley could have had Crawford based on his team’s dismal record. As it turned out the Athletics had the first pick of the ’65 draft and took another Southern California native — outfielder Rick Monday, who three years earlier declined a bonus to sign with Lasorda and the Dodgers out of Santa Monica High but go to play at Arizona State.

At the time of the signing, the Associated Press said Crawford, at 6-foot-2 and 200 pounds, had been timed in 3.1 seconds getting from home plate to first. It noted Crawford’s bonus was the second-highest paid by the team, behind the $107,000 given to 21-year-old Frank Howard in March of 1958.

The Dodgers knew they could send Crawford to the minor leagues for some indoctrination to pro ball, but he had to be on the MLB roster that season eventually and all of ’65. Starting nearby at Single-A Santa Barbara, Crawford got into 98 games and hit .299 with an .827 OPS, stealing 17 bases to go with eight homers and 34 RBIs, plus 23 doubles and five triples.

So now, just nine days after his 18th birthday in September of 1964, Crawford made his Dodger debut, wearing No. 43. It was the fifth inning at a game at Dodger Stadium against Pittsburgh — the Dodgers’ starting outfield was Willie Davis in center, Tommy Davis in right and utility player Darrell Griffith in right, the spot Crawford could be groomed for. The Pirates had Clemente as their right fielder, maybe a subtle reminder to the fans who saw Crawford face right-hander Vern Law as a pinch hitter and pop out to short.

On Sept. 29, a Tuesday night game at Dodger Stadium against the Cubs, Crawford started in right field, batted leadoff and went 3-for-5 with a double. In the third inning, he singled, stole second, went to third on the throwing error, and scored on a sacrifice fly to give the Dodgers a 3-0 lead. He started and batted leadoff that whole three-game series. By the end of the trial run, he had five hits in 16 at bats for a .313 average. Maybe this could work.

A month after the season ended, the Los Angeles Times noted that Crawford would be marrying his 17-year-old “high school sweetheart” Delores Johnson at Phillips Temple Christian Methodist Episcopal Church in South L.A. The “Dodger Way” was continuing to show its impact on players’ lives and routines.

Topps issued its first card of Crawford in 1965 as a “Rookie Star” pairing with third baseman John Werhas. It noted above his minor-league stats that he “showed promise in ten games for the Dodgers” the previous season, but it also made sure to include that he “signed with hometown Los Angeles” and threw out that $100,000 figure. It would be part of Crawford’s identity.

The next season, the Dodgers run to the 1965 World Series title saw them at one point trailing San Francisco by 4 1/2 games in the NL standings with 15 games to play. The Dodgers won 13 straight to pull off the pennant. Crawford, by rule with the team the full year, only got into 52 games, covering 27 at bats, and hit just .148. Ron Fairly was moved from first base to right field to make room for Wes Parker, so the outfield spots were spoken for. Then when former batting champ Tommy Davis was injured and out for most of the season, Lou Johnson became the new starter. Crawford still waited.

One consolation was Crawford made the post-season roster. His pinch-hit single in Game 1 of the World Series was a success; striking out in his pinch-hit appearance in Game 6 was not so much. Both at bats came against the Twins’ Mudcat Grant. Crawford still ended up with a World Series championship ring.

The ’65 season was also a reflection of the turbulent times marked by the Watts Riots in late August. Crawford’s home was not far from the disruption — same with teammates John Roseboro and Lou Johnson — and it was reported that Crawford was actually arrested as a rioter and later released (according to the 2011 book, “The Greatest Game Ever Pitched, Juan Marichal, Warren Spahn and the Pitching Duel of the Century.”) The L.A. Times reported that Crawford had “to pick he way through the curfew area to get to his home in the rioting district.”

In the same story, manager Walter Alston was quoted about Crawford: “It would have benefited him so much to have played every day for one of our farm teams. I seldom get a chance to use him except as a pinch runner. He’s one of the hardest workers on the team. He has actually improved even without seeing much action.” Crawford also told The Daily Breeze that season his year-around training in the Arizona Instructional League included him “drag bunting all the time — even with the bases loaded.”

At the time of the riots, on Aug. 19., the Dodgers were involved in an epic 15-inning game in San Francisco during the pennant race. That contest included the incident where Crawford came in a pinch runner in the top of the 12th — starting pitcher Don Drysdale, still in the game, singled to start the inning and Crawford came in, was bunted to second by Maury Wills, and then looked as if he would score on Don LeJohn’s pinch-hit single to center. But Crawford realized he missed third base and had to go back. The next hitter, Jim Lefebvre, hit a grounder back to pitcher Gaylord Perry, who threw Crawford out at the plate trying to score. The Dodgers eventually won 8-5, and three days later was the well-known contest where Juan Marichal hit Johnny Roseboro with his bat during an heated dispute. The Dodgers and Giants split the four-game series and the Dodgers kept a slim lead atop the NL standings.

In 1966, Crawford could play 140 games at Double-A Albuquerque, hitting .265 yet striking out 186 times. He led the Texas League with 94 runs and 14 triples. Back at the end of the season, he was 0-for-6 and left off the Dodgers’ World Series roster against Baltimore.

In the Dodgers’ rebuilding year of ’67, Crawford put in 163 games at both at Albuquerque and Arizona Instructional League, hitting .293 with 25 homers, 94 RBIs and 14 triples to go with 21 steals, and making the Texas League All Star team. But he struck out 150 times. Crawford made it into four Dodgers games in September, striking out three times in four at bats, with one hit. At just 20 years old, he still couldn’t break into the starting outfield of Davis, Fairly and Johnson.

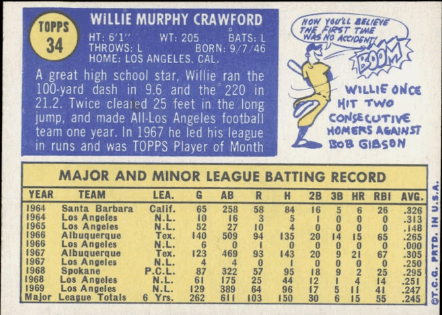

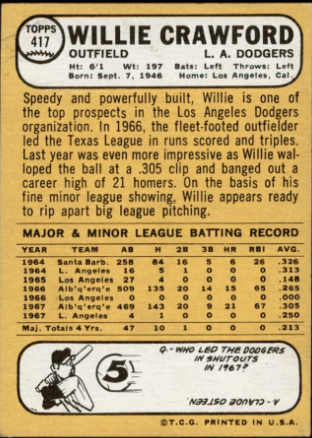

When 1968 arrived, even though he appeared in games from ’64 to ’67, Crawford still had not made enough appearances and was classified as having rookie status. He changed to No. 27 (he had also been wearing No. 47 off and on). His new Topps No. 417 card proclaimed: “Speedy and powerfully built, Willie is one of the top prospects in the Los Angeles Dodgers organization … On the basis of his fine minor league showing, Willie appears ready to rip apart big league pitching.”

He still began the first part of the year with Triple-A Spokane in the Pacific Coast League and hit .296 with a team-high 12 stolen bases and nine triples in 87 games. He only hit two homers, but he walked 45 times.

Even though the Dodgers had three left-handed hitting outfielders, Crawford came up for 61 games with the Dodgers starting in mid-July. He hit .251, striking out 64 times, and a .735 OPS. His first big-league homer came off the Phillies’ Dick Hall in early September.

The next two were quite impressive: Having just turned 22 years old, Crawford would hit homers off the St. Louis Cardinals’ Bob Gibson, who was finishing off an historic season in the “Year of the Pitcher” where he would sport an MLB-record 1.12 ERA. Crawford led off a game against Gibson in St. Louis with a homer on Sept. 11 at Busch Stadium. The next came in the seventh inning of a Sept. 22 Sunday afternoon game during a 3-2 Dodgers win, which dropped Gibson’s record to 21-9 as the team was gearing up for the World Series run.

By the 1969 season, Crawford must have felt like the oldest 22 year old on the roster.

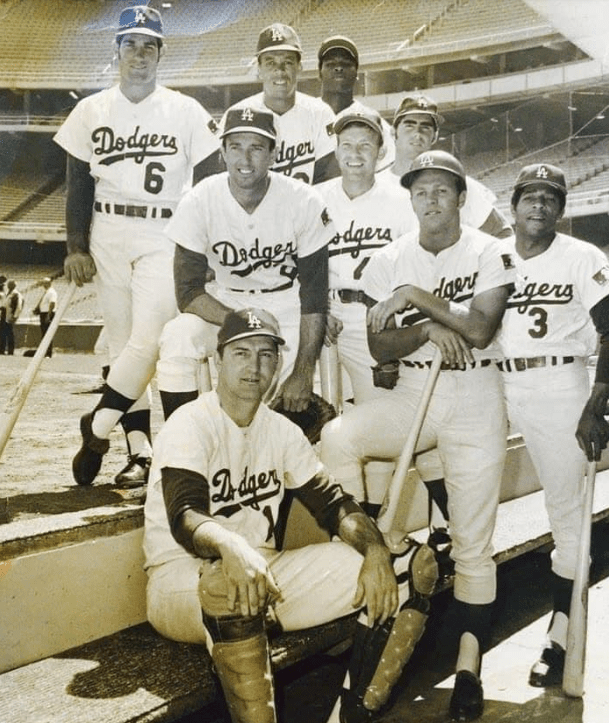

There would be no more grooming in the minor leagues — but the Dodgers starting outfield was most often set with Davis, Manny Mota and Andy Kosco. Crawford got into 129 games, the same as Davis, and hit .247 with 11 homers and 41 RBIs, plus five triples and 17 doubles. This was also the pivot point in the Dodgers’ franchise as a new wave of young draft picks were emerging: Von Joshua, Bill Buckner, Steve Garvey, Bill Russell, Ted Sizemore, Bill Sudakis and Bobby Valentine, all age 19 to 21, getting some late-season at bats — just as Crawford had five seasons earlier.

The group was referred to by some as “The Mod Squad,” after the popular TV show at the time. Crawford picked up on that as he came to spring training that year sporting a large Afro hairstyle — but it was just a wig, something to get a laugh from his teammates. However, Crawford was involved in a spring training incident with pitcher Mike Strahler when back-and-forth joking went too far. At one point, Crawford took it to be hurtful and punched Strahler, breaking his nose. Red Patterson, the Dodgers’ publicity manager, denied rumors that it was racially motivated, and Crawford agreed to pay for Strahler’s medical bills.

Platooning in right field with the right-hand hitting Mota in 1970 season, Crawford started in the April 7 season-opener at Dodger Stadium against Cincinnati. Reds starter Gary Nolan gave up only two hits in a 4-0 win over the Dodgers — Crawford had both hits, as he batted cleanup.

At age 23, Crawford’s 109 games resulted in just a .234 average, eight homers and 40 RBIs, plus four stolen bases. He struck out 88 times, second most on the team. In 114 games in 1971, Crawford improved to .281 with nine homers and 40 RBIs and was surprisingly better against left-handed pitchers: 20 for 53 for a .377 average. When the Dodgers acquired Frank Robinson prior to the 1972 season to add more offense, Crawford was back to hitting .251 with eight homers and 27 RBIs in 96 games.

As it turned out, Crawford credited Frank Robinson, his winter ball manager in 1971, for helping him with a better approach to hitting — don’t pull the ball as much, use the entire field, stop trying to hit home runs every time up.

With Robinson traded to the Angels the next season, Crawford seemed to figure things out and put together his two most productive seasons back to back, hitting. 295 in ’73 and in ’74, combining for 25 homers, 127 RBIs and 19 stolen bases those two seasons. Yet, 179 strike outs against 273 hits.

He was the NL Player of the Month in May of ‘73: In 27 games he hit .404 with five homers and 20 RBIs. That year, Crawford had also joined Buddhism and began meditating before games with teammate Willie Davis.

On the Dodgers’ 74 NL pennant winning team that posted a 102-60 record, Crawford, who at 27 had been with the Dodgers the longest of anyone on the roster to that point (Willie Davis was traded to Montreal), platooned in right field with Joe Ferguson, as Jimmy Wynn was the new center fielder. In the NLCS against Pittsburgh, Crawford was 1 for 4 in two games. In the World Series against Oakland, he was 2-for-6 in three games. A ninth-inning solo home run in Game 3 at Oakland off A’s reliever Rollie Fingers pulled the Dodgers closer in an eventual 3-2 loss.

In 1975, Crawford kept his position in the outfield status with Wynn and Bucker but hit .263 with nine homers. Younger players were pushing behind him for time. The Dodgers’ acquisition of Dusty Baker before the 1976 season signaled another pivot. That spring, the Dodgers decided to trade Crawford to St. Louis and reacquire backup second baseman Ted Sizemore. Perhaps, with the Cardinals, Crawford could play every day.

Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray wrote at the time: “Willie’s is a classic case of arrested athletic development. A big-muscled, powerful young man in the Lou Gehrig mold, Willie Crawford, like Gehrig, has the body and configuration that must be used every day to stay at peak efficiency.”

Crawford was also quoted in the L.A. Times: “I felt I was stereotyped in a position by the Dodgers with no way to break it.” He said he “never had the type of communications” with Dodgers manager Alston “that I should have, but I don’t leave with ill feelings. I simply feel there was a need for a change of scenery. I was in a rut. I was not getting any younger and my situation wasn’t improving.”

In St. Louis, Crawford hit .438 in April and .326 in May of ’76. It was good enough so that the Cardinals traded right fielder Reggie Smith to the Dodgers to opening a starting position for Crawford. He hit .304 that season, but only .225 with runners in scoring position.

After stops in San Francisco, Houston and eventually with Finley’s team in Oakland (and wearing an odd No. 99 while hitting just .184 in a 98-loss season), Crawford, now 31, accepted an invitation as a free agent with the Dodgers in February of ’78. Crawford would be in the mix as the left-handed pinch-hitting specialist with Vic Davalillo and Ed Goodson. He showed up to camp “far overweight” by one report and the Dodgers released him on March 31 as spring training ended.

Daily Breeze columnist Mike Waldner wrote a couple days after that how Lasorda had seen Crawford’s career, from signing him, to nurturing him in the minor leagues as a coach, then managing him. “The Crawford story is loaded with frustration at every turn. Lasorda preaches about the fruits of victory. Crawford never saw a harvest. It would be unfair and unkind to call Crawford a failure. You don’t last 14 years in the majors without being able to play the game. On the other hand, the great success predicted for him when he signed for $100,000 out of Freemont High in Los Angeles was never realized. … All Crawford wanted was the opportunity to play regularly. All the Dodgers wanted from him was to win the job from other capable candidates.” Waldner noted that the Dodgers — Lasorda and Campanis — decided young Glenn Burke was to stay with the last roster spot, meaning Crawford had to go. “The Dodgers are not without a sentimental streak. They would have loved having Crawford play for them this summer. The fact that one of ‘Lasorda’s guys’ did not stick with the team tells you they are all business.”

Later that year, in May, it was noted that Crawford had visited the Dodger Stadium press box and he was hitting .340 for the Mexican League’s Aqua Calientes. “However,” the story noted, “he’s out with a broken nose suffered in a brawl.”

Crawford’s 12 seasons with the Dodgers amounted to 989 games, a .268 average with 437 runs, 74 homers, 29 triples, 125 doubles and 45 stolen bases (caught 35 times). Eric Stephens at TrueBlueLA.com noted that Crawford’s 118 OPS+ ranking 39th in franchise history among batters with at least 2,000 plate appearances, just ahead of Dusty Baker, Mike Marshall and Manny Mota, a tick below Adrian Gonzalez and Jeff Kent.

Crawford played two more years in the Mexican League, and wanted in 1979 to play for the Panama Banqueros of the new Inter-American League as a DH/first baseman, but the franchise disbanded.

Bruce Markusen, the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s manager of digital and outreach learning and the author of several baseball books, has done extended research about Crawford’s career. Markusen wrote about the time in 2004 when he started a research project on Crawford, drawn by the oddity of Crawford wearing No. 99 for the Oakland A’s in 1977.

Markusen’s opinion after his extensive research was that Crawford, early in his career, “made the mistake of trying to hit home runs rather than simply trying to make hard contact. The approach didn’t work.” He called Crawford’s outfield play “crude and somewhat clumsy … much to be desired.”

Markusen uncovered a 1973 interview that Crawford did with Black Sports Magazine and revealed that moment in his career that was frustrating him.

“You know, from a statistical and monetary point of view, my career has been sort of a disappointment,” Crawford told writer Kenneth Bentley. “I know a lot of people claim I haven’t lived up to my potential, but that’s hogwash. Nobody can live up to their potential not playing regularly, and I haven’t played regularly since I got into the big leagues.”

Markusen also found that Crawford struggled with alcohol after his career ended. He wrote:

One night, he was drinking from a bottle of vodka while listening to a sermon by Billy Graham. Something clicked at that moment of desperation as Crawford began to cry — he called up Campanis, asking him for help. Campanis reached out to two former Dodgers, Lou Johnson and Don Newcombe, who had also struggled with alcoholism before receiving the help that they needed. Johnson and Newcombe convinced Crawford to start attending meetings of Alcoholics Anonymous.

Crawford did just that, but he still felt he needed more. He checked himself into The Meadows, a renowned clinic that specialized in helping alcoholics. With help from The Meadows, Crawford stopped drinking.

“When you drink, you’re trying to suppress something,” Crawford told freelance writer Steve Calhoun. “The Meadows helped me find out why I was drinking. I was suppressing anger. I felt that I always had to fight for respect.”

More specifically, Crawford was angry about his career, that he had almost always been a platoon player, and rarely given the chance to play every day.

Crawford found peace in that area of his life, but another problem would eventually develop. He was stricken with kidney disease, which left him debilitated.

After a struggle of several years, he succumbed to the disease in late August of 2004. He was just 57, several weeks short of his birthday.

Markusen would write in conclusion of several posts he did on Crawford:

Crawford’s life was too short, but it was a good life, nonetheless. By all accounts, he was a popular and well-liked teammate. … he was a hard-working player and showed up at the ballpark early and did his best to develop his skills. He had the good humor that helped him connect with everyone, regardless of skin color.

Never forgetting his roots in Watts, he was the kind of man who went home each winter and held baseball clinics for kids in his old neighbhorhood. And he did find a way to overcome his addiction to alcohol, making his life better after his playing days had ended.

I never got that chance to communicate with Willie Crawford, but my research turned up something just as important – a good man. Willie Crawford made the game a little bit better during his short life, and ultimately, that’s all we can ask of one of our heroes.

Crawford’s hometown never forgot him. In 2015, the California Interscholastic Federation named its All-Century spring team — the top 100 high school athletes from baseball, tennis, swimming and track in California going back to 1896. Crawford was included for his baseball career as was Pasadena Muir’s Jackie Robinson, Oakland McCylmonds’ Frank Robinson and Van Nuys’ Don Drysdale. The 100 athletes picked came from a public online voting.

In Crawford’s 2004 obituary, after his death at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in L.A., those who saw him were able again to marvel at his talent.

“He could have gone on to college and been one of the true great football players,” Lasorda said. “He was big and powerful, and he could hit a ball as far as anybody. Boy, was he something. He had so much ability. He was loaded.”

Crawford’s headstone at Forest Lawn in the Hollywood Hills includes a profile of him in a Dodgers uniform and cap and reads: “Beloved husband, father, grandfather and friend to many who will be in our hearts forever. We love you always”

Who else wore No. 27 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

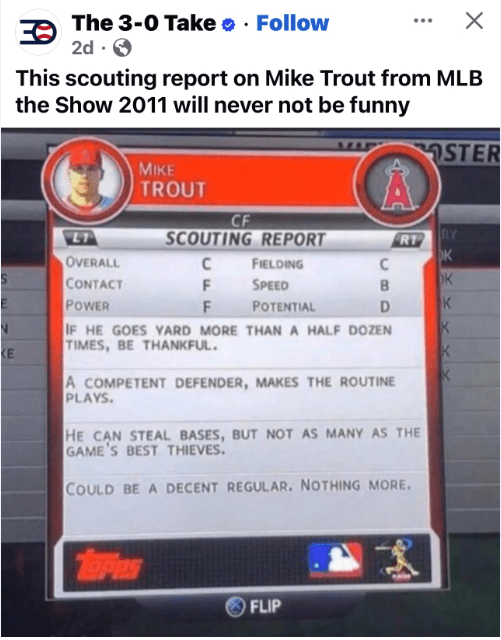

Mike Trout, Los Angeles Angels outfielder (2011 to present):

The 2012 AL Rookie of the Year, three AL MVP Awards (2014, ’16 and ‘19), four second-place MVP finishes (’12, ’13, ’15 and ’18) and a lifetime WAR stat in his first 10 years that just knocked the historians sideways made it all but a sure thing that Mike Trout had a ticket punched for Cooperstown. The 10-year requirement is official bottom-line time frame required for Hall of Fame consideration.

What more does he have to do? Stay healthy, perhaps. And maybe, by chance, have his team make the playoffs.

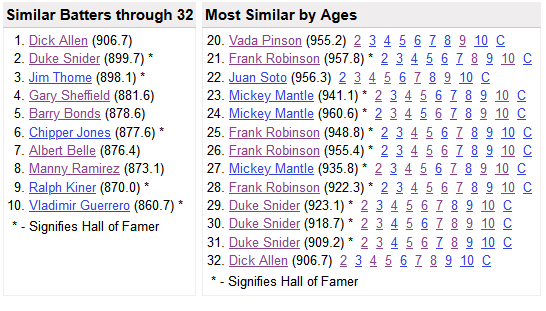

On Baseball-Reference.com, it is astounding to see how Trout aligns, year to year, to players of the past, only statistically mind you, through his age 32 year. The Mickey Mantle comparisons pan out, not just visually, but from hard data.

Especially, considering early data like this:

In 2019, when Trout committed to a $426 million contract to stay with the Angels through 2031, when he would be 44 years old, reaching some $37 million a year — the richest deal at the time in North American sports — he said he was sold on the team’s approach, convinced that owner Arte Moreno was committed to building up the team, even if it meant paying more luxury tax.

The Angels were already in decent shape when they took the New Jersey native in the first round (25th pick overall) in the 2009 June amateur draft, and the Millville Meteor was made his big league debut at age 19 in July of the 2011 season. The next season, the team waited until the end of April to bring him in, and in just 139 games he led the AL with 129 runs and 49 stolen bases to go with a .326 average, 30 homers and 83 RBIs. His average was as high as .357 in July. He could have been the Rookie and Year and MVP. By every metric, Trout was the “best player in the Major Leagues.” In Joe Posnanski’s “The Baseball 100” listing of the 100 greatest players in the game as of 2020, Trout was at No. 27. The active player with the highest WAR at 86.2 after the 2024 season, it is 50th best of all time. From 2012 to 2016, he led the AL for five straight seasons in WAR, twice hitting 10.5. If his career average is 9.2 each season for the last 14 seasons, it would give him, by the end of 2028, a 142 WAR, which would be No. 8 all time.

Since signing that mega-deal, Trout has had six managers and four general managers. If he avoids more injuries, and can put up more numbers, it will be a joy to watch where this all ends out. For years, the hashtag #FreeMikeTrout has popped up on social medua during baseball season. However, Trout doesn’t want to be freed. Trout remains in one of the biggest media market areas and continues to avoid a lot of spotlight. His play speaks for itself. Still. His health is another concern.

“I’ve got (five) more years on the contract,” Trout told The Athletic in September of 2025. “That’s what fuels me. I feel like I’ve got a lot left in my tank. And I know when it’s right, I can be the best.”

Vladimir Guerrero, Anaheim Angels/Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim outfielder (2004 to 2009):

The first Hall of Famer to have an Angels logo on his bronze plaque, “Vlad the Impaler” spent just six of his 16 MLB seasons in Anaheim. But over that time, between the ages of 29 and 34, they included the ’04 AL MVP in his first season there, two more top-three AL MVP finishes, four AL All Star appearances and four Silver Sluggers. Plus five AL West championships. The ever-aggressive swinger already had 234 homers, 702 RBIs and 123 stolen bases in eight seasons with Montreal to go with a .323 average.

Coming to the Angels in a free-agent deal — a five-year, $70-millon contract — he put up 173 more homers, 616 RBIs and hit .319. The Dodgers failed on two key chances to have him in their roster. He spent eight months in their Dominican academy and the team declined to sign him — they took instead his older brother, Wilton, and had another brother, Albino, in their system. The Expos gave him $2,500. Battling a herniated disc in his final year in Montreal, some teams held back on signing him as a free agent. What held the Dodgers from signing him was complications as the team ownership was transferring from Fox to Frank McCourt, so the Angels and Arte Moreno jumped in. In his first season, he hit .500 (15 for 30) with a 1.783 OPS, six homers, three doubles, 11 RBIs, 10 runs, six walks and zero strikeouts in 36 plate appearances over his last eight games as the Angels went 7-1 to overcome a three-game deficit and overtake Oakland for the division title on the second-to-last day of the season.

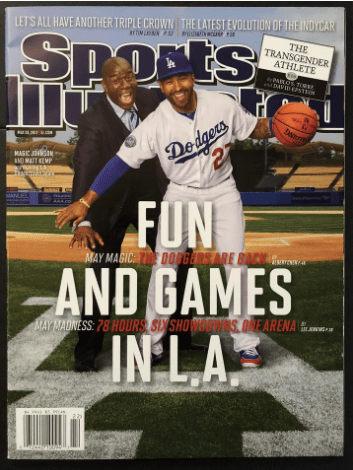

Matt Kemp, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (2006 to 2014, 2018):

Matt Kemp’s NL MVP runner-up in 2011 to Milwaukee’s Ryan Braun, after leading the league with 39 homers, 126 RBIs, 115 runs and 353 total bases, on top of his first NL All Star appearance, a Gold Glove and a Silver Slugger, will remain one of the most debated award votes in MLB history. Especially years after Braun, the Hebrew Hammer out of Granada Hills High, admitted to steroid use after insisting he was clean. The Dodgers tried to make that all clear when “Matt Kemp Day” took place in 2024 — complete with a bobblehead giveaway — to acknowledge his contributions during Alumni Weekend. It also allowed him to sign a one-day contract and official retire with the Dodgers, with 10 of his 15 seasons already in L.A. where he accumulated 203 homers, 733 RBIs and his .292 with 170 stolen bases in more than 1,200 games. His three NL All Star appearances all came with the Dodgers, including a return in ’18 after being away for four seasons, and he hit .290 with 21 homers and 85 RBIs. Kemp came to reflect the Dodgers’ return to the spotlight after the sale of the franchise to the Guggenheim company, which included Magic Johnson as one of the partners, and a 2012 Sports Illustrated cover to reflect the new vibe.

Alec Martinez, Los Angeles Kings defenseman (2009-10 to 2019-20):

The right guy at the right time. Martinez, who wore No. 57 his first two seasons from ’09 to ’11, scored 5:47 into overtime in Game 7 of the Western Conference Finals against Chicago to put the Kings into the Stanley Cup Final. Just 12 days later, in Game 5 of the championship round against the New York Rangers, he scored on a rebound from Tyler Toffoli’s shot with 5:17 left in the second overtime and clinched the Stanley Cup for the franchise, their second in three seasons. A few months later, he signed a six-year $24 million extension — but he was traded to expansion Las Vegas in 2020, where he won two more Stanley Cups.

Kevin Brown, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1999 to 2003):

Because of the time and place in the game’s financial history, someone had to be the first mercenary to receive a $100 million contract. It was Brown, and the Dodgers needed it, dancing with the Scott Boras client, giving him five seasons at $107 million despite his age (34), but mostly because the four-time All Star was coming off an 18-win season and World Series appearances with Florida and San Diego. The Dodgers won the offseason with this deal by GM Kevin Malone. It included a $5 million signing bonus, a no-trade clause, and 12 chartered flights for his wife and children from Georgia to L.A. each year. An 18-win season in ’99 and 3.00 ERA in a league-high 35 starts included five complete games and a shutout. He had one more complete game in 2000, making the NL All Star team (which he repeated in ’03), but never completed a game after that. His 2.58 ERA in 2000 also led the NL, allowing him a 58-32 record over his five seasons (before he was traded to the New York Yankees, who picked the last two years of his $15.7 million annual salary as the Dodgers were trying to cut payroll in an ownership turnover). His 2.83 ERA over 129 starts was admirable, but Brown never did pitch in the postseason for the Dodgers and was injured enough and the target of criticism by media and the fans to make his time in L.A. seem rather forgetful.

Todd Zeile, Los Angeles Dodgers third baseman/catcher (1997 to 1998):

Starring at Hart High in Valencia, Zeile made himself into one of the gerat UCLA baseball players in its history during a three-year run (1984 to ’86), becoming part of the school’s Athletic Hall of Fame in 2008. As a sophomore, he led UCLA with 12 home runs, most ever by a Bruin catcher at the time, and followed it up as a junoir batting . 366 with 13 home runs and 43 RBIs and earning All-Pac-10 honors. Signing as a free agent with the Dodgers prior to the ’97 season, Zeile was included in a trade to Miami with Mike Piazza midway through the ’98 season. It was with some interesting symmetry that Zeile have some of his 16-season MLB career in Los Angeles. Ziele was born in Van Nuys on Sept. 9, 1965 — during Sandy Koufax’s perfect game pitched at Dodger Stadium. His dad listened to Vin Scully’s call of the game while he was in the hospital waiting room.

Jose Lima, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2004): The only season of his 13-year MLB career as a Dodger was punctuated by a complete-Game 3 victory over St. Louis in the 2004 NLDS. The “Lime Time” five-hit shutout was the Dodgers’ only win in a four-game series loss. That has been the Dodgers’ first playoff series in eight years and the first post-season win at Dodger Stadium since 1988. Six years later, Lima died of a heart attack at age 37.

Jennie Finch: La Mirada High School softball (1994 to 1998):

Time magazine referred to Finch as “the most famous softball player in history” during a 2008 story recapping how the U.S. women’s softball team had to settle for a silver medal at the Beijing Olympics. That started at La Mirada High, where she was he CIF Division II player of the year as a sophomore and lettered all four seasons in the sport, as well as two seasons each in basketball and volleyball. Wearing No. 27 through high school, at the University of Arizona and on the U.S. Olympics and other pro softball endeavors, she threw six perfect games, 13 no-hitters and was 50-12 at La Mirada with a 0.15 ERA and 784 strikeouts in 445 innings. She also played shortstop and first base when she wasn’t pitching. A gold medal in the 2024 Olympics and the silver in ’08 saw her go 4-0 during the competition on the mound. She had a 119-16 record at Arizona with 1.08 ERA and a Honda Award as the sport’s top player and then played five years of professional softball.

Scott Niedermayer, Mighty Ducks of Anaheim/Anaheim Anaheim Ducks defenseman (2005-06 to 2009-10): The 2007 Conn Smythe Trophy winner and team captain when the franchise won its first Stanley Cup, Niedermayer was a Hockey Hall of Fame defenseman signed as a free agent with Anaheim after his first 13 seasons in New Jersey. He marked his team as a two-time All Star, scoring two overtime playoff goals in the 2003 season. He led the Ducks with 54 assists in the ’06-’07 season to go with 15 goals.

Theotis Brown, UCLA football running back (1976 to 1978): A 2011 inductee in the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame, Brown set the Bruins’ single-game rushing record with 274 yards against Oregon in ’78. He finished his career as the Bruins’ single-season leader in all purpose yards with 1,804 in ’78, and was second in career rushing yards (2,914) and touchdowns scored (27). He also left as the career leader in all-purpose yards (3,944).

Have you heard this story:

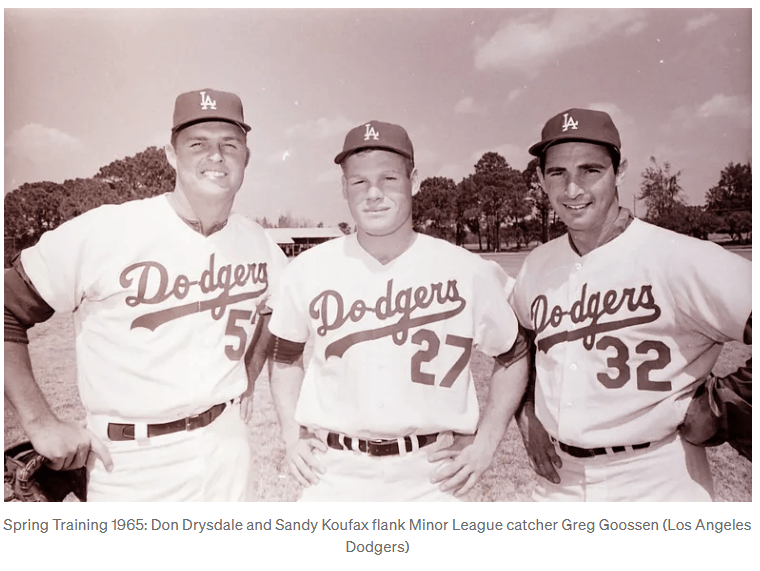

Greg Goossen, Los Angeles Dodgers catcher (1964):

Signed as an 18-year-old right out of Sherman Oaks Notre Dame High School, Goossen was dispatched to the Dodgers’ rookie league team on Pocatella, Idaho and then Single-A St. Petersburg, Fla., before he was invited to the Dodgers’ spring training facility in Vero Beach prior to the 1965 season. From that, came this photo — Goossen flanked by Don Drysdale and Sandy Koufax. By April of 1965, Goossen was picked off by the New York Mets in an $8,000 waiver draft. The story of this photo: Goossen had it signed for his brother, Joe, who had been in a car accident. But the family misplaced it over time. An image in the Dodger archives did not have a caption, but, as team historian Mark Langill once explained, it “always stayed in the back of my mind because Drysdale and Koufax didn’t have that many photo-ops with a subject in the middle.” In 2009, when I did a 40-anniversary feature story on Goossen being part of the one-and-only season of the Seattle Pilots in 1969, Goossen mentioned the photo and what it meant to him. I contacted Langill, and he knew immediately what I was talking about. A duplicate was made, and Goossen received the photo when he came to Dodger Stadium to take in a game and also meet broadcaster Vin Scully. “I never thought I’d see this again,” Goossen said. “I’ve been looking for this for 40 years!”

Goossen, who died two years later, may have never played for his home-town team. Scout Tommy Lasorda and Al Campanis had visited his San Fernando Valley home to sign him on the June night he graduated from Notre Dame High, outbidding the Houston Colt .45s before Goossen injured a knee in a fight. But Goossen experienced one of the most unusual trips through MLB history — and beyond. Casey Stengel, Gil Hodges and Ted Williams were among his MLB managers. He caught Nolan Ryan’s first game. He was involved in a 1970 trade for Curt Flood who, at the time, was having his 1969 trade from St. Louis to Washington heard as a case in the U.S. Supreme Court as Flood fought baseball’s reserve clause.

His SABR bio goes much deeper into his journey. A 1991 Los Angeles Times story has more. Our obituary wraps it all up, including the fact Goossen was about to be enshrined in the Notre Dame High Sports Hall of Fame on the night that he died. “Doesn’t it seem like this is just the sum total of all the heartbreak he had in his life – just missing here, just missing there?” asked Jim Bouton, who gave Goossen his most prominent place in pop culture history as one of the main characters from the 1969 Pilots in the groundbreaking book “Ball Four.” Bouton continued: “He was sort of on the fringe of everything – an extra, but never the star. And now, after all these years, they’re about to bestow him the highest honor for his high school, one more round of laughter, waving and thanking his family and friends … and he’s denied all that again?”

Bob Davenport, UCLA football (1953 to 1955):

A fullback out of Long Beach Jordan High, Davenport was a two-time All-American pick and part of the Bruins’ 1954 national championship team. Davenport was one of several key players who were on Red Sanders’ 8-2 team in 1953, and then started the ’54 season with a 67-0 win over San Diego Navy at the Coliseum. In week three, UCLA hosted the defending national champions Maryland to the Coliseum and in front of 73,000 on a Friday night, Davenport ran for 89 yards on 23 carries and scored both touchdowns in a 12-7 Bruins victory. UCLA ended its 9-0 season with a 34-0 win over USC before more than 102,000 at the Coliseum. Because of the no-repeat rule, UCLA wasn’t allowed to go to the Rose Bowl, but settled for a national title based on UPI voters. Davenport’s senior season saw UCLA finish 9-2, 6-0 in the PCAA, and a final No. 4 ranking. In a 17-14 loss to Michigan in the ’56 Rose Bowl, Davenport put UCLA on the board with a two-yard TD run. A draft pick by the Cleveland Browns, Davenport declined playing in the NFL because of games played on Sunday and instead spent two seasons in the Canadian Football League. He was a 1985 induction into the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame.

Irv Cross, Los Angeles Rams cornerback (1966 to 1968):

He’s in the Pro Football Hall of Fame — for his long run with CBS and its iconic Sunday morning NFL pregame show, receiving the Pete Rozelle Radio-Television Award from the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2009 as the first African-American to receive the honor. As a player, he had two Pro Bowl seasons with the Philadelphia Eagles before he was traded to L.A., playing behind the famed Fearsome Foursome line, and had six interceptions (one returned for a 60-yard touchdown in ’66) and five fumble recoveries, starting in 40 of his 42 games.

The mystery:

On Figueroa Avenue outside the Los Angeles Coliseum, this history signpost explaining the facility’s legacy has this prominent photo of a USC football player wearing No. 27. Any ideas who it could be? he’s not identified in any of the cop surrounding the illustrations.

We also have:

Trevor Bauer, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2021)

Phil Regan, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1966 to 1968)

Lou Johnson, Los Angeles Angels outfielder (1961)

Pat Thomas, Los Angeles Rams defensive back (1976 to 1982)

Danny Maloney, Los Angeles Kings left wing (1973-74 to 1974-75) Also wore No. 17 in ’72 and ’73.

Glen Murray, Los Angeles Kings right wing (1996-97 to 2001-02)

Anyone else worth nominating?

3 thoughts on “No. 27: Willie Crawford”