This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 74:

= Kenley Jansen, Los Angeles Dodgers, Los Angeles Angels

= Merlin Olsen, Los Angeles Rams

= Ron Mix, USC and Los Angeles Chargers

The most obvious choices for No. 75:

= Deacon Jones, Los Angeles Rams

= Howie Long, Los Angeles Raiders

= Irv Eatman, UCLA football

= Eddie Sheldrake, UCLA basketball

= Max Montoya, UCLA football

The most obvious choices for No. 76:

= Rosey Greer, Los Angeles Rams

= Marvin Powell, USC football

= Joe Alt, San Diego Chargers

= Al Lucas, Los Angeles Avengers

The most obvious choices for No. 85:

= Jack Youngblood, Los Angeles Rams

= Lamar Lundy, Los Angeles Rams

= Antonio Gates, Los Angeles Chargers

= Bob Chandler, Los Angeles Raiders

=Dokie Williams, UCLA football, Los Angeles Raiders

The most interesting stories for Nos. 74, 75, 76 and 85:

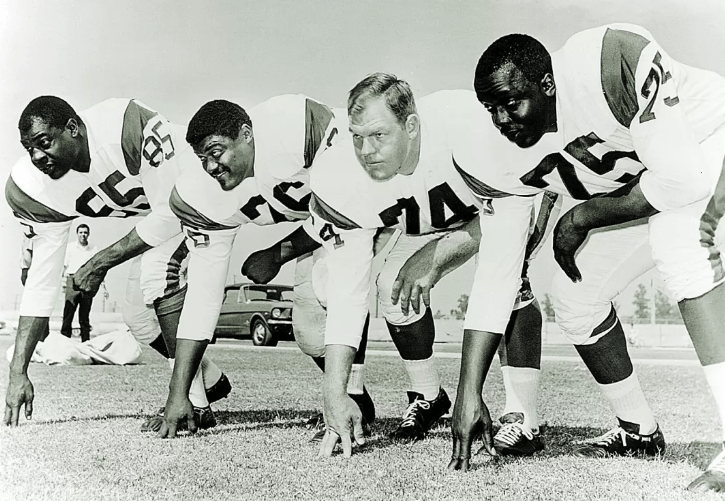

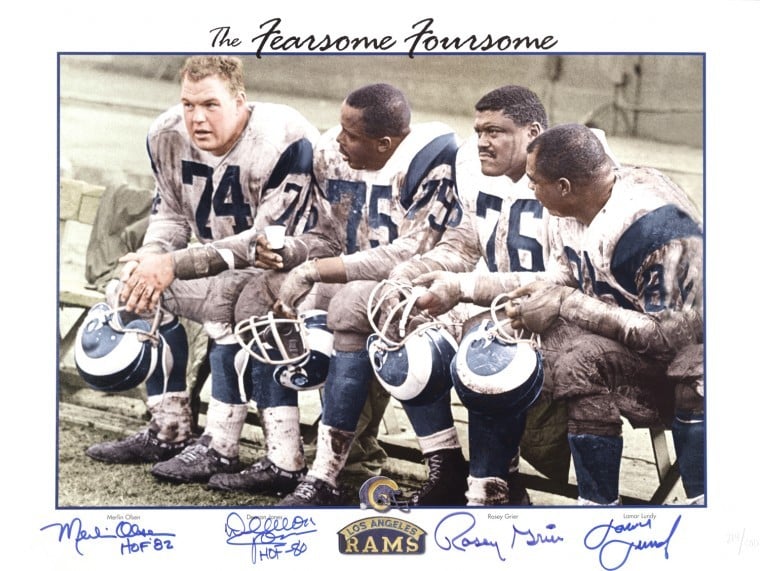

Merlin Olsen: Los Angeles Rams left defensive tackle (1962 to 1976)

Deacon Jones: Los Angeles Rams left defensive end (1961 to 1971)

Rosey Grier: Los Angeles Rams right defensive tackle (1963 to 1966)

Lamar Lundy: Los Angeles Rams right defensive end (1957 to 1969)

Southern California map pinpoints:

L.A. Coliseum, Chapman College, Hollywood

When the New York Times’ posted a version of its daily “Connections: Sports Edition” puzzle in October of 2025 — participants are challenged to reveal four groups of four things that go together — it should have been a foregone conclusion that “famous nicknames for NFL defense” would include …

(Four, three, two, one …)

The Fearsome Foursome.

Some nerve.

Merlin Olsen, Deacon Jones, Rosey Greey and Lamar Lundy many have only unnerved opposing offenses as a quintet for just four seasons. But that in no way gives anyone permission to call them The Four Seasons.

It’s also interesting to note that during their alliterative convergence from 1963 to 1966, the Rams only won 22 of their 56 games. The team had offensive deficiencies.

Sure, in the history of the NFL, other collectives honored for their ferocious nature has led to even a Wikipedia page to document it. But here in the 2020s, not even four score and a few years after they thundered about on the Coliseum floor, the Fearsome Foursome couldn’t forged its way into a pop culture quiz about NFL nicknames.

Maybe this is another teachable moment.

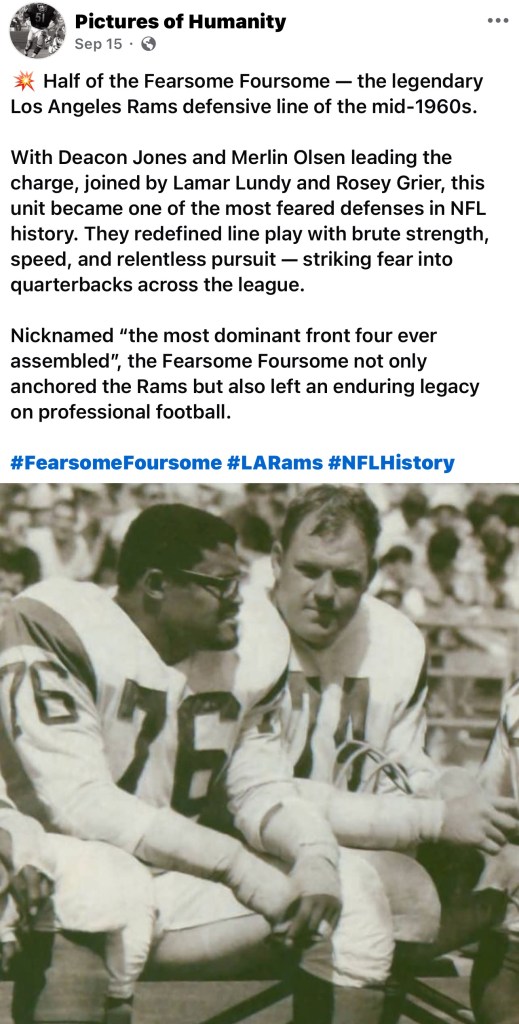

“We taught the NFL the beauty of playing defense,” Deacon Jones told Sports Illustrated in 2001, during one of those “Where are they now?” editions to remind readers of this century what happened awhile back shouldn’t be forgotten. It was, of course, Jones, upon nicknaming himself as the Secretary of Defense, who coined the phrase “quarterback sack” for a stat that would become ubiquitous for players at that defensive line position.

As the Los Angeles Times’ Mal Florence explained it during a story about them in 1985, a generation after their departure: “If the Fearsome Foursome had lived in another time, they probably would have been part of a marauding army, sacking cities instead of quarterbacks. There was something majestic about those four distinct personalities … to popularize and set the standard for defensive linemen. They had size and range and were always on the attack. And they did it with flair and elan that were inimitable.”

Too bad that sacks were not an officially recorded as an NFL statistic until 1982, and solo tackles and assisted tackles didn’t become logged in until 1994, and quarterback hits have only been recorded since 2006. The quantifiable data can’t tell us how these four Rams might butt heads with modern-day players.

That all adds to their mystique. And it falls more on remembering their interlocked uniform numbers: 74, 75, 76 and 85.

“I think we did some real pioneering in essence on the defensive side of football,” Merlin Olsen told the Times’ Florence. “We helped people appreciate for the first time some of the team effort that a defensive line initiates, or a group of linebackers and secondary. A lot of those groups have come forward since that time.

“We were pioneers in another way. I think we were one of the first teams, if not the first, to incorporate stunts into blitzes and (red) dogs as a regular part of defensive patterns.”

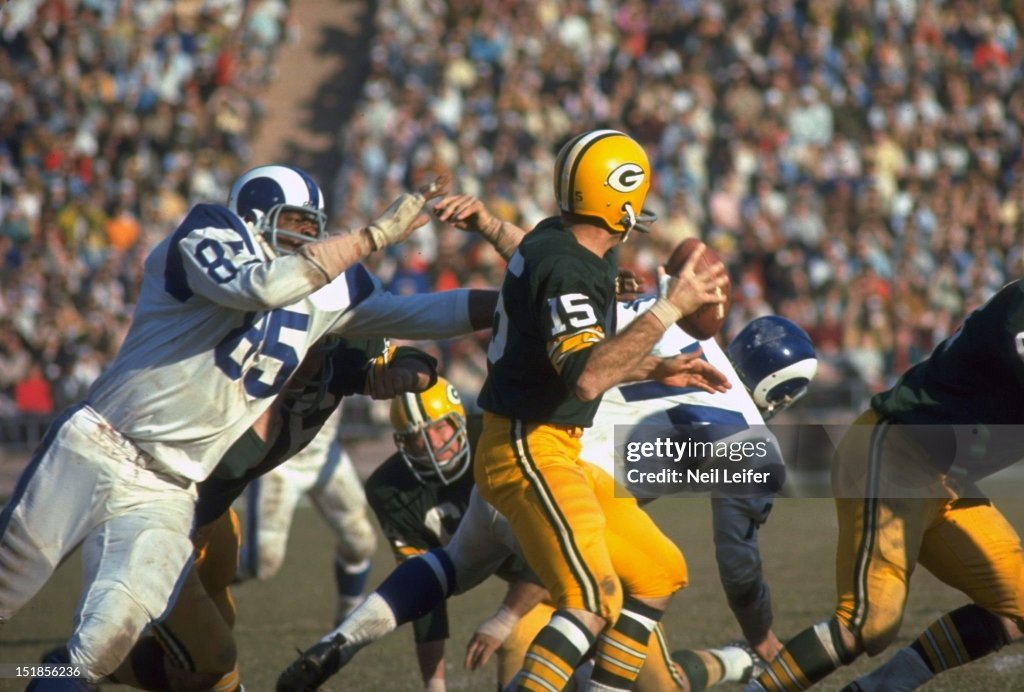

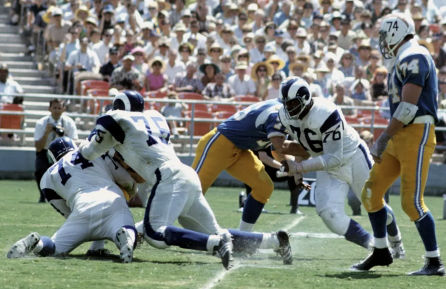

As the NFL offense then was centered around the value of the power running game, the Fearsome Foursome fought back with strength in numbers. Should the quarterback decide to then pass, and take too much time in the pocket, there was even more push back.

“Our philosophy was that they can’t double team all four of us,” Olsen said.

Jones brought the head slap into the tools of the trade. Now outlawed, he admitted Grier taught him how to do it and perfect it. Jones explained how they worked together and measured their successes:

“Lundy would grade out better than anyone across the line. The gamblers, like myself, don’t grade out that high. I was quick off the ball, but I wasn’t as quick as Rosey. In 10 yards, he could run with anyone and that’s all a lineman needs. I did copy his ability to slap. But I did it to keep the tackle’s eyes closed.

“Merlin had superhuman strength. If I was beating my man inside, he’d hold him up and free me to make the tackle. If he had to make an adjustment to sacrifice his life and limb, he would make it. A lot of the plays I made were because he or the others would make the sacrifice.”

Quarterbacks were the ones ultimately sacrificed.

The background

The Rams of the early ’60s were in desperate straights. They wore a 1-12-1 record in 1962, the worst in franchise history.

Former star player Bob Waterfield quit as the head coach midway through it all, and Harland Svare took over. The Rams were trying to get a foothold at a time when the Dodgers had just moved out of the Coliseum to start playing in their own stadium, and USC football under new coach John McKay had just posted an 11-0 record in ’62, winning the national championship. As the NBA’s Lakers were quietly playing next door at the Sports Arena, the Rams, who had won an NFL title more than a decade ago, were teetering on becoming obsolete in Southern California sports.

Prior to the ’63 season, Rams general manager Elroy Hirsch made a trade with the New York Giants — swapping out the team’s younger right defensive end John LoVetere and a draft pick in order to pick up veteran Pro Bowl right defensive tackle Rosey Grier. The 6-foot-5, 284 pounder was a seven-year veteran and already 31 years old. He was part of a Giants’ line with Andy Robustelli, Jim Katcavage and Dick Modzelewski that, in a 1957 New York Daily News’ headline, was first referred to as “A Fearsome Foursome.”

Grier’s arrival at the team’s training camp at Chapman College was to line up next to Lamar Lundy. The 6-foot-7, 245 pounder had been playing RDT since 1960 when he arrived from Purdue in 1957 as a flanker and played three years there before he was moved to defense. Lundy moved to right defensive end.

On the left side, Deacon Jones, at 6-foot-5 and 272 pounds, had been the Rams’ defensive end since 1961. A season later, Merlin Olsen, at 6-foot-5 and 270 pounds, became the new defensive tackle out of Utah State and was christened the NFL Rookie of the Year.

Jones brought the swagger, Grier brought the leveraging power and experience. Lundy had the reach, Olsen was the glue, as he would miss only two games over 15 seasons.

Call me Deacon, Jones had already told the L.A. media, because “I’ve come to preach the gospel of winning football to the good people of Los Angeles.” Jones’ actions already spoke louder than his words. In his first year playing at South Carolina State, the school revoked his scholarship when it learned he participated in a protest during the Civil Rights Movement. Jones transferred to Mississippi Vocational College (which became Mississippi Valley State) and seemed like a steal when the Rams took him in the 14th round of the 1961 draft after they scouting him by accident when looking at film for a running back. Although Jones started as an offensive lineman, his nature moved him to the other side of the ball.

Jack Patera was the Rams’ defensive line coach during their four seasons were together. Svare had been the New York Giants’ defensive coordinator with Grier before coming to the Rams so he knew of his capabilities.

Grier, who’d also become known for his needlepoint abilities, made this a tight-knit unit. All they needed was love, he said.

“When I was with the Giants, I could be a clown,” Grier said once. “They had a lot of leaders. We didn’t have that many leaders in L.A. I decided that’s what they needed. So I took a stand and the Fearsome Foursome came together. … we loved each other.”

That ’63 team didn’t quite sparkle. It lost its first five and its last three games during a 5-9 finish, sixth in the seven-team West Division. On the stat sheet, again unofficial at the time, showed Lundy with nine sacks, Jones and Grier with six each, and Olsen tallying 3.5 out of the team’s 27 total.

In ’64, during a 5-7-2 campaign, Jones was piled up 22 sacks in those14 games. Lundy had eight, Olsen had seven and Grier had 6.5 of the team’s 49. By then, Chicago Bears tight end Dick Butkus called them “the most dominant line in football history.”

In ’65, during a 4-10 slog, Jones registered 19 sacks, Olsen had six, Lundy had 2.5 and Grier had 1.5 of the team’s 32. That season cost Svare his head coaching job.

And in ’66, as George Allen came in and pushed the team above .500 at 8-6, Jones had 16 sacks, Lundy had 11.5, Grier had seven and Olsen had four of the team’s 45 total.

In a preseason game played in September of 1967, Grier suffered an Achilles injury. He thought he could come back. That didn’t happen, and he eventually had to retire. As the offense finally figured out that Roman Gabriel was their up-and-coming leader, that Dick Bass could carry the ball, and there was an offensive line worth its weight, the Rams added new parts to its defensive line, unwilling to give up its “fearsome” mantra.

Pro Bowl tackle Roger Brown (6-foot-5, 300 pounds) came over from the Detroit Lions and pulled on No. 78 for Los Angeles. Brown had been part of a defensive line in the early ’60s that was dubbed the “Fearsome Foursome” by broadcaster Van Patrick — it included Alex Karras, Darris McCord and Bill Glass.

Not only did the L.A. media welcome Brown but it wouldn’t retire the nickname as the Rams flipped to 11-1-2 in ’67, tied with Baltimore for the league’s best record as both were in the newly aligned four-team Coastal Division. Jones punched in 21.5 sacks — or 26 according to other sources — while Lundy had 7.5, Brown bagged seven and Olsen had 3.5 to combine for 40 of the team’s 43 total.

The fact Brown had three seasons with the Rams, and the team saw its greatest success in years, seems curious as to why he wasn’t better remembered as part of the Fearsome Foursome lore. Maybe it didn’t fit the narrative. This was like a pre-’80s boy band. You just keep moving new names and faces in.

In ’68, Jones tied his career high with 22 sacks, capping off an NFL Defensive Player of the Year honor for the second year in a row. Olsen had nine sacks and Brown 3.5. Lundy played only five games because of a torn knee and had two sacks. Gregg Shuchumacher, a 26-year-old left defensive tackle (wearing No. 81) started nine games, pulled in an impressive 8.5 sacks, but that would be the end of his two-year NFL career. Linebacker Jack Pardee also had 4.5 sacks.

More change in ’69: As Jones had 15 sacks with Olsen pulled in 11, Lundy was hobbled and couldn’t play in more than four games. Diron Talbert (No. 72) stepped in and started 13 times at right defensive end, logging 7.5 sacks. Brown now came off the bench, but had five sacks. Coy Bacon, fresh out of Jackson State, started 13 games at right defensive tackle, registering eight sacks while wearing Grier’s old No. 76.

The 1970 season saw Brown and Lundy retire. Bacon switched to No. 79. Jones’ 12 sacks was one more than Bacon’s 11 (plus a fumble return for a touchdown), with Talbert adding 11.5, and Olsen registering 8.5. The Rams as a team had 53 sacks and gave up just 23, which better explained a 9-4-1 season under Allen. But after that, Allen left to coach the Washington Redskins.

Tommy Prothro came over from UCLA after six seasons to become the Rams’ head coach in 1971. Bacon had a team-high 11 sacks, while Jones, in 10 games, had 4.5. Phil Olsen, Merlin’s brother, came in as the right defensive tackle (No. 72) and started eight games, landing four sacks. He shared that spot with Bill Nelson (No. 67), who had four more sacks. Merlin Olsen added four sacks in his 14 starts.

The 10 sacks that Merlin Olsen college in ’72 was just behind the 10.5 Bacon had for the team lead. By ’73, Olsen had seven sacks, but with Bacon gone to San Diego, the team leaders were new left defensive tackle Jack Youngblood (No. 85, Lundy’s former number) with 16.5 sacks, and right defensive end Fred Dryer (No. 89) with 10 sacks. Larry Brooks (No. 90), the new left defensive tackle, had nine sacks.

Olsen pulled in 3.5 sacks in ’74 as the Rams finished 10-4 under Chuck Knox, losing to Minnesota in the conference championship. Dryer and Youngblood had 15 each and Brooks had 11. Olsen had 7.5 sacks in ’75 at age 35, again starting all 14 games, behind Youngblood (15), Dryer (12) and new left defensive tackle Cody Jones (No. 76), who had 4.5 sacks.

The last of the original Fearsome Foursome retired in 1976 — Merlin Olsen called a career at age 36, collecting his final three sacks — and the Rams won another division title, only to lose to Minnesota in the NFC championship. Youngblood and Brooks led the way with 14.5 sacks each and Dryer had five, with rookie Mike Fanning (No. 79) adding four.

And that was a wrap.

The legacy

On the ProFootballReference.com statistical history of the Rams franchise, a category called “Approximate Value” was created to “attach a single number to every player’s season since 1960.”

Olsen is listed as the franchise’s career-best “AV” of 167, even ahead of Aaron Donald’s 153. Olsen was the team’s seasonal “AV” leader as a rookie in ’62 as well as in 1970.

From 1964 to 1968, Jones was the team’s “AV” leader for five straight years and had a career “AV” of 134 (eighth all time with the Rams).

Olsen retired as the Rams’ all-time leader in tackles with 915, although, again, it’s not all official. Olsen was named to the NFL’s 75th Anniversary All-Time Team in 1974 and had the unique experience to play with his brother Phil (6-foot-5, 265 pounds) on the Rams from 1971 to ’74, and against his third younger brother, Orrin, who was in the NFL for one season as a 6-foot-1, 245-pound center for the Kansas City Chiefs.

Merlin Olsen and Deacon Jones were the only two of the four to have their numbers retired by the franchise as well as be inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

ProFootballRefernce.com researchers, putting together information from game film and other resources to try to quantify defensive stats from games going back to 1960, credits Jones as the Rams’ franchise leader in sacks with 159.5. His career totals of 173.5 would put him No. 3 all time on the “unofficial leaders” list, behind Bruce Smith (200) and Reggie White (198), who are Nos. 1 and 2 on both official and unofficial lists. Merlin Olsen is fourth all-time in the Rams’ franchise with 91.0 sacks. Lundy had 60.5; Grier had 21 in his fours seasons and Brown added 15.5 in four seasons that followed.

Jones is rated at No. 16 and Olsen is No. 30 in the 2023 book “The Football 100: The Story of the Greatest Players in NFL History.” Olsen was also on The Sporting News’ list of the 100 Greatest Football Players of All Time in 1999, coming in at No. 25.

For Jones, the “Football 100” book pulls a quote from his 1996 autobiography, “Headslap,” that goes: “I have a mean streak, and in my business, I needed it, or I never would have made it. Pro football is, after all, a pain-giving game. My head slap gave pain. It made you not want to hold me at the line, which is the one illegal move offensive linemen get away with over and over in every game. My head slap was the right hand of Joe Frazier and Muhammad Ali rolled into one.”

“The Football 100” also quotes L.A. Times columnist Jim Murray comparing what Babe Ruth did for offensive baseball, Jones did for defensive football.

“He was a genius at it,” Murray wrote.

The NFL now gives out the Deacon Jones Award to the player with the most sacks recorded in a season.

Jones could recall his most memorable sack was off Atlanta’s Bob Berry, which knocked the quarterback’s helmet off.

“If his helmet doesn’t go, his head does,” Jones would say.

Olsen became the gentle giant of Hollywood actors — “Father Murphy,” and Jonathan Garvey from “Little House on the Prairie” — as well as an esteemed television game analyst for years on NBC with Dick Enberg as his partner. He was also a believable spokesman for telemarketing flowers. Bouquets to him for his amazing career on and off the field, which included a successful Porsche/Audi car dealership in Encino.

Grier also went into movies and TV, but was more a political activist and recognized as an ordained minister. As a bodyguard, Grier put his thumb behind the trigger of Sirhan Sirhan’s gun to prevent him from firing the weapon any further after he had already assassinated Robert Kennedy at the Ambassador Hotel in L.A. in June of 1968.

He was referred to “Forrest Grier” in a Sports Illustrated story for his Gumpian ability to be on so many consequential moments in history.

In the summer of 1972, Grier was the co-headliner of a bleak Blaxploitation sci-fi comedy – if that’s a real genre — called “The Thing With Two Heads,” where he played an specifically type-cast African-American convict about to go to the electric chair (Prisoner No. 4031). He decides to donate his body to science instead and is taken to a transplant center where a dying mad professor/white bigoted doctor (Ray Milland) wants to attach his head to a more robust body.

Roger Ebert gave it a mild thumbs in his movie review, and added: “The publicity for the movie warns against the possibility of ‘apoplectic strokes, cerebral hemorrhages, cardiac seizures or fainting spells’ during the movie, but they’re just trying to make themselves look good. The only first aid they really need is hot coffee for the patrons who doze off.”

He may have tried to be the next NFL-turned-film star like Jim Brown, Jim Kelly or Fred “The Hammer” Williamson, but he ended up being an ordained minister in 1983, a role model for inner-city teens, and a nationally known fan of needlepoint. He was the only one of the four who lived long enough to see the Rams return to Los Angeles in 2016 and win their first Super Bowl for the city.

Lundy may have been the only one of the original four to not stay in the public limelight, battling a serious muscle disease after he retired. Lundy also struggled with diabetes and a thyroid ailment during his career.

Jones said in a 2008 story that he met Lundy coming in as a 1961 rookie and “when I got there, things were completely different than they are now. We were all coming out of a segregated world and we needed leadership among ourselves. I needed a mentor and Lamar was just a solid player and solid gentleman. We met during the course of training camp and became tight friends. He really helped me out during my rookie year and I don’t know if I would have made it through my first season without him.”

Lundy, also in the Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame, credited Grier with giving him a better outlook on life as he battled physical issues. It was part of the idea that these four would remain friends to the end.

“Rosey is very involved in religion, and a year ago he came to see me and started talking,” Lundy said in that ’85 interview. “I was on the other side of the spectrum as far as religion was concerned. But now that I have accepted Jesus Christ it seems like my world has turned around, the mountains have been moved. I feel good inside.”

“Whoever got the most publicity of the group — Merlin, Rosey or Deacon — we were still looked at as a group. The reason we are remembered is that we were successful as a group.”

Grier, a draft pick by the Giants out of Penn State in 1955, remains the last living member of the group, turning 93 in July, 2025.

Lundy died at age 71 in 2007. Olsen died at age 69 in 2010. Jones died at age 74 in 2013.

Other teams had nicknames for their defensive lines — the 1969 USC Trojans, for that matter, came up with “The Wild Bunch, an ode to the Sam Peckinpah spaghetti western at the time. It came to define Marv Goux’s line of Al Cowlings, Jimmy Gunn, Bubba Scott, Charles Weaver and Tody Smith, and there’s even have a statue dedicated to them next to Heritage Hall. It was revived years later by Mike Patterson, Kenechi Udeze, Shaun Cody and Omar Nazel.

In the NFL, the Jets had their “New York Sack Exchange” and the Broncos had the “Orange Crush” defense.

Why couldn’t the Rams come up with some more creative — the Los Angeles Rush Hours might have worked. Or the Rams’ Horn O’ Plenty.

That’s for the more creative types. This Fearsome Foursome also demonstrates how legends can be born of things that maybe we even misremember all of the reality actually attached to them.

In a 2025 Los Angeles Times feature on the Los Angeles Rams’ defensive line of Byron Young, Kobie Turner, Braden Fiske and Jared Verse, there was a lot of “Fearsome Foursome” channeling. They even recreated a photo of the four lined up in a three-point stance.

Verse even talked about meeting Grier during a commercial photo shoot.

“The coolest part about it is we’re talking about that group 50 to 60 years later,” Fiske said. “I mean, that’s unbelievable. … For a whole group to make their mark is something that is still considered one of the best is something we chase.”

“They had their time, and now we have our time to make a name,” Young said.

There have been many suggestions, the players said. But none that has yet to be adopted.

“If one shows up that’s really nice,” Turner said, “then we’ll rock with it.”

Who else wore No. 74 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

Kenley Jansen, Los Angeles Dodgers relief pitcher (2010 to 2021), Los Angeles Angels relief pitcher (2025):

The native of Curacao came to the franchise as a 6-foot-5, 265-pound catching prospect and took No. 74 because it was the street number where he grew up. By age 22, he showed his worth by striking out 41 in 27 innings during 25 games in 2010. He would surpass 100 strikeouts four times (and reach 99 once and 96 in his second year) despite throwing less than 77 innings. A three-time NL All Star, he led the NL with 41 saves in 2017 (a year after collecting 47) to go with a 1.32 ERA and 5-0 record. His 12-year run with the Dodgers allowed him to amass a franchise record 350 saves, nearly 200 more than runner-up Eric Gage. After spending four years of free agency in Boston, Jansen returned to Southern California and wore No. 74 for the Angels in Anaheim.

In 2013, the Los Angeles Times’ Bill Plaschke wrote: “The Dodgers’ bullpen is a dizzying array of beards and tattoos, its inhabitants marked by checkered pasts and chips on shoulders. All of which makes Kenley Geronimo Jansen the weirdest one of all. ‘You don’t have to look like a tough guy,’ he said softly. ‘When the situation comes up, you just have to be a tough guy.’ …. (His) midseason emergence has made a (Yasiel) Puig-like impact on the pitching staff. (He) takes the mound looking like a giant kid in his pajamas. His giant arms have no tattoos. His whispery voice has no edge. His soft eyes are wide and wandering. He doesn’t drink. He doesn’t party. He is 25 years old and still lives with his parents.”

Joseph Deng, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2025): Maybe a bit premature, but a notable signing by the team — Deng, a 6-foot-7, 185-pound, 17-year-old righthander, is the first player from South Sudan to sign a professional baseball contract.

Ron Mix, USC offensive lineman (1956 to 1959), Los Angeles Chargers right tackle (1960):

The career of the Pro Football Hall of Famer started as what he called “one of the least talented players in our starting lineup” at Hawthorne High. A Jewish kid who originally grew up in the Boyle Heights neighborhood, Mix considered going to El Camino College with hopes of transferring to UCLA but his size and potential caught the attention of USC end coach Bill Fisk at a high school post season All Star game. He accepted a USC scholarship and began as an offensive and defensive end, wearing Nos. 85 and 83. He even led USC with one interception in that spot in 1957. As one of the few who lifted weights, he continued to grow bulk and strength, and transitioned to tackle. In 1959, he helped terrorize Pitt’s backfield en route to a 23-0 win. The team captain also recovered a fumble to set up a score in a 17-8 victory over Baylor later that year. His defensive playmaking along with outstanding blocking earned him an All-American nod to cap his Trojan career. Mix kept No. 74 as the AFL’s Los Angeles Chargers got him in a draft trade from the Boston Patriots and signed him for $12,000 plus a $5,000 bonus after he turned down the NFL’s Baltimore Colts’ offer of $8,000. Mix started all 14 games as a rookie, making the AP All-Pro first team. Mix then followed the franchise’s move to San Diego where he made eight straight Pro Bowls. Mix, inducted into the Hall in 1979, is one of only 20 who played all 10 seasons of the AFL’s existence and won a title with the Chargers in 1963. “One of the best offensive lineman I’ve ever seen,” said Chargers coach Sid Gillman. Mix made a statement before the 1965 AFL All-Star Game set for New Orleans that if Black players weren’t allowed to eat in certain restaurants, then he would refuse to play. More teammates joined Mix’s protest and the game was moved to Houston. When Mix decided to retire from the Chargers after the 1969 season he was lured back to play for the Oakland Raiders in 1971. Chargers owner Gene Klein was so upset he took Mix’s No. 74 out of retirement and put it back into circulation. Of the Chargers’ six retired numbers, Mix’s No. 74 is still not among them.

Who else wore No. 75 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

Howie Long, Los Angeles Raiders left defensive end (1982 to 1993):

Following his rookie season with the team in Oakland, Long started in 151 games during the Raiders’ L.A. run and made eight Pro Bowls. Also a member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame’s All-1980s team, and he was an official Hall of Fame member in the Class of 2000. On the NFL’s unofficial list of career sack leaders, Long was credited with 91.5, tied for No. 85, and one-half ahead of Merlin Olsen. And he can tell you all about it every Sunday morning from the Fox Studios lot.

Irv Eatman, UCLA offensive lineman (1979 to 1982), Los Angeles Rams offensive lineman (1993):

A two-time Lombardi Award semifinalist, two-time All-Pac-10 pick and three time honorable mention as an All American, he capped off his college career on the Bruins’ 1983 Rose Bowl win.During an 11-year NFL run, after three years in the USFL, he was able to circle back to play for the Rams in ’93, starting all 16 games at left tackle.

Max Montoya, UCLA offensive right guard (1977 to 1978):

Born in Montebello, a standout at La Puente High and Mt. San Antonio College, Montoya gravitated to UCLA and was a two-year starter. That launched an NFL career that included four Pro Bowl appearances, including one during his time wearing No. 65 for the Los Angeles Raiders (1990 to ’94).

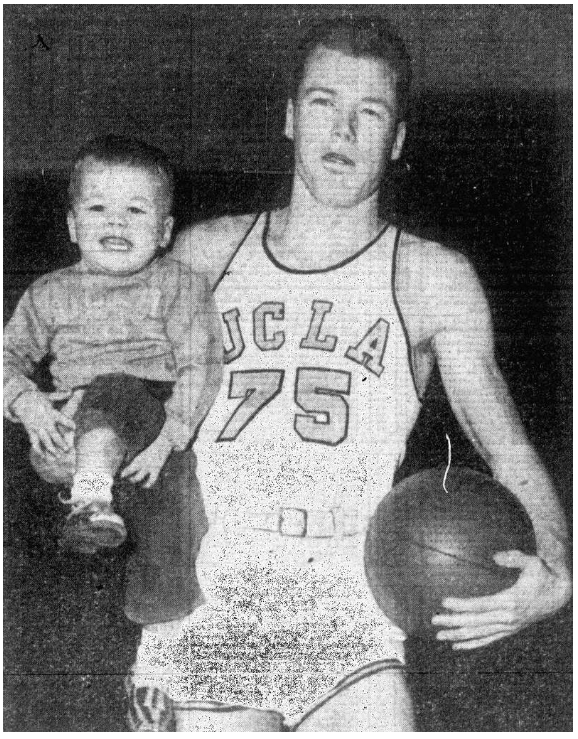

Eddie Sheldrake, UCLA basketball guard (1948 to 1951):

It seems odd that a 5-foot-9, barely 120-pound guard out of L.A.’s Washington High and captain of John Wooden’s Bruins team at a senior in ’51 would sport such a large number like 75. The rules in place usually called for players to wear nothing larger than 55 so referees could signal fouls to the scorekeeper with their hands. Sheldrake, named to the United Press’ “Little All-American” team of players 5-foot-10 and under, was a Navy aviation mechanic before he went to UCLA and set a school record with 38 points against Stanford as a senior, the year he actually started at forward. Nine members of the UCLA team moved on, so Sheldrake went back to guard, the position he had during his first two seasons of varsity play as he was captain of the Bruins’ freshman team in ’47, setting a record with 262 points. As a sophomore, Sheldrake started the last two games of the season against USC and led his team with 17 points in the first encounter. As a senior, Sheldrake won the Coach Caddy Works Award for competitive spirit and contribution to the team. During Sheldrake’s time on Wooden’s first three varsity teams, the squad went 65-24 and won three Southern Division championships, including UCLA’s first full conference title and NCAA appearance in 1950.

After UCLA, Sheldrake played NIBL and AAU basketball for the Los Angeles’ Kirby’s Shoes squad, leading the team to a 12-0 mark as its captain in ’51-’52 and staying through 1957. Also wearing No. 75.

Even though he was inducted into the UCLA Athletics Hall of Fame in 2000, his Wikipedia bio rightly claims Sheldrake as a far more famous restaurateur. He and his brother Don started opening Kentucky Fried Chicken stores in the Belmore Shores area of Long Beach in 1965. Then they started the Polly’s Pies chain in Fullerton in 1968, naming the store after the newborn daughter of their manager. Today the Polly’s Pies restaurant chain has 13 stores located through Los Angeles County, Orange County and Riverside County.

Sheldrake died at age 98 on May 18, 2025. He was inducted into the Orange County Hall of Fame in ’25.

Matt Kalil, USC football center (2008 to 2011): The 6-foot-6, 315-pounder out of Servite High, younger brother of Trojan All-American center Ryan Kalil, Matt also won the Morris Trophy as the Pac-12’s top offensive lineman and became the fourth overall pick by Minnesota in the 2012 NFL Draft. In early 2026, Matt Kalil was in the news for reportedly suing his ex-wife, model Haley Kalil, for making public statements about his private parts as being a reason behind the end of their marriage in 2022.

Who else wore No. 76 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

Al Lucas, Los Angeles Avengers defensive tackle (2004 to 2005):

On Sunday afternoon on April 10, 2005, the news shook up not just Arena League Football followers but also those Los Angeles-area football fans: During an Avengers game at the downtown Staples Center against the New York Dragons, the 6-foot-1 and 300 pound Lucas made a tackle on a kickoff return just minutes into the game as the crowd of 11,000 were still filing into the arena. Dragons kick returner Corey Johnson, with teammate Mike Horacek directly in front of him, came toward Lucas. He ducked low to get past a blocker and collided with both Johnson and Horacek at about the 15-yard line, well clear of the Arena Football League’s sponsored dasher boards. Johnson’s knee and upper thigh smash, and Horacek’s leg, hit Lucas’s head at precisely the wrong angle.

“I didn’t see or hear anything that was different than what I’ve seen a million times,” Avengers coach Ed Hodgkiss said at a press conference the next day. Lucas twisted his neck, fell unconscious and never got up. Attempts to revive him failed. After he was taken to a local hospital and pronounced dead, the team wasn’t informed until after the game, which the Avengers won, 66-35. Lucas, who was 26, was survived by his wife and young daughter. It was a rare case of a death occurring on the field during a live game. Lucas suffered an upper spinal cord injury caused by blunt force trauma, contact that seemed like a normal football play. The team retired his No. 76 the next season and several memorial funds were set up in his honor by his alma mater, Troy State in Georgia, and other organizations. The AFL Player of the Year and Hero Award were named in his honor. In 2004, Lucas led the Avengers with 18.5 tackles, three sacks, three fumble recoveries and a safety. Going into that Week 10 game against New York, Lucas had made nine tackles and four assisted tackles that ’05 season.

Marvin Powell, USC football offensive tackle (1974 to 1976):

A College Football Hall of Famer, Powell was a two-time All-American and a key member of the ’74 national title team. Trojans went 29-6-1 in his career. After majoring in political science and speech at USC, Powell returned to college for six off-seasons to earn his Juris Doctor from New York Law School in 1987. He had four Pro Bowl seasons in the NFL with the New York Jets and became president of the NFL Players Association.

Joe Alt, Los Angeles Chargers offensive tackle (2024 to present): The 6-foot-8, 321-pound two-time All American from Notre Dame was made the No. 5 overall pick in the 2024 NFL draft by the Chargers.

Who else wore No. 85 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

Jack Youngblood, Los Angeles Rams defensive end (1971 to 1984):

The resume includes having Sports Illustrated, in a 2007 celebrating the greatest professional athletes to wear the uniform numbers, calling him the best No. 85 of all time, a number the team has retired. Elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2001, Youngblood was a seven-time Pro Bowl player, five-times first-team All Pro and 1970s “All Decade Team” member. He played in 201 consecutive games, a Rams team record, and only missed one game in his 14-year NFL career. His 151 sacks are second only to Deacon Jones in Rams’ franchise history, and on the league’s unofficial list of career leaders, Youngblood would be No. 6 all time.

Oh, and he played not only in Super Bowl XIV at the Rose Bowl in 1980, as well as two prior playoff games, with a broken leg.

Youngblood, who led the NFL with 18 sacks in 1979, helped the Rams come back from a 5-6 start to win their last four in a row, somehow take the NFC West and face Dallas in the first round of the playoffs. As they took a 14-5 halftime lead, it was apparent Youngblood was hurt. Team doctor Clarence Shields told him his leg was broken. “I said, ‘Tape it up, Clarence. … I can still run, tape this dadgum thing up’,” Youngblood told CBS Sports. “He said, ‘Jack, I don’t know how to tape.’ My orthopedic doctor doesn’t know how to tape (laughs).”

The leg was taped up and Youngblood helped preserve a 21-19 win in the final moments with a sack of Roger Staubach, who retired after the game.

In the NFC title game, a 9-0 win over Tampa Bay, Youngblood played with an extra pad protector in the leg.

In the Super Bowl against Pittsburgh, the Rams’ 13-10 halftime lead disappeared when Terry Bradshaw, Lynn Swan and John Stallworth went to work in the second half, as Youngblood kept chasing the future Hall of Fame quarterback around the field.

Youngblood went to Hawaii the next week to play in the Pro Bowl.

“Everybody asked me when we got to Hawaii, ‘What the heck are you doing here? You’ve got a broken tibia,'” said Youngblood, who became the Rams’ radio analyst Also the Rams’ radio analyst from 1987 to 1991. “I said, ‘Shut up, I’m not going to miss this party.’ … I mean, we went through the season, and now it’s time to let your hair down a little bit. We do have to go out and compete a little bit. But it wasn’t nearly as intense. It was a show. Let me put that away.”

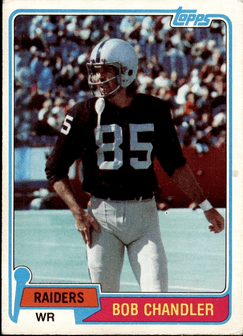

Bob Chandler, Los Angeles Raiders receiver (1982):

On the wall of his dark office space could be a framed magazine cover — when he posed for Playgirl’s special Christmas Double Issue of 1981. It’s the one with Warren Beatty on the cover, and down in the right corner it teases: “Celebrity Nude! The Oakland Raiders’ Bob Chandler – He’ll Be Catching More Passes Now.” “I never wanted notoriety for anything other than my playing ability,” Chandler told Sports Illustrated’s Douglas Looney at the time. “That’s why I had no notoriety. Strange, isn’t it that after 11 years of busting my ass on the football field, I get the most attention for spending eight hours exposing my ass?” Chandler was preparing then for his 12th NFL season at that point a few dozen catches shy of the 400 milestone. From 1975 through 1978, he caught 220 passes for the Buffalo Bills, more than any other receiver in the league during that period. SI also pointed out that somehow Chandler was never picked for a Pro Bowl. Maybe his offensive contributions were overshadowed on that Bills squad by teammate, running back and friend O.J. Simpson. After missing almost the entire 1979 season with a separated shoulder, Chandler came back in 1980 to lead the Super Bowl-champion Oakland Raiders in receptions with 49, including 10 for TDs, tied for second in NFL scoring catches. At age 32, despite missing most of the first half of the season with a ruptured spleen, Chandler had 26 receptions and four TDs, plus the highest yards-per-catch average, 17.6, of his career. He was back in Southern California at age 33 for what was his final NFL season with the newly-moved Raiders but played just two games in 1982 because of a knee injury. He retired for good before the 1983 season started, ending up with an average of 14.2 yards a catch, with 370 receptions and 48 touchdowns. One last quip from Chandler from that SI piece is how we’d like to remember him: “In the total scope of life, I’ve accomplished nothing. Except that I have gotten to bide my time and be a kid for a long while. And it’s fun being paid a lot of money to be a kid.”

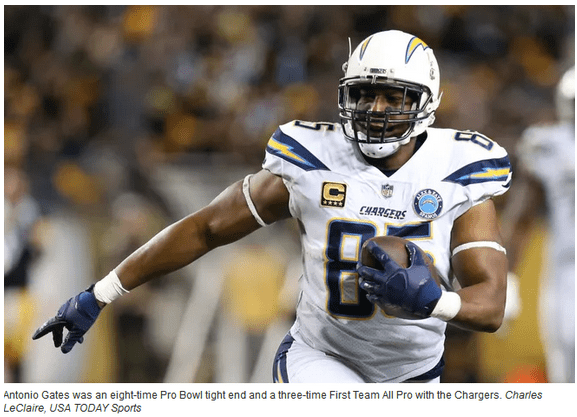

Antonio Gates, Los Angeles Chargers tight end (2003 to 2018):

The eight-time Pro Bowl player played his final two seasons in L.A. after the first 10 in San Diego, collecting 955 receptions for 11,841 yards and 116 touchdowns, the latter more than any tight end in NFL history. It earned him a Pro Football Hall of Fame induction in 2025. How good was he? Former teammate and quarterback, Philip Rivers explained “The Gates Rule” within the team’s offense philosophy: ”That just meant if Antonio Gates is one on one, that overrides all other things. We can talk through a read all you want. But if there’s one guy on Gates and you like the matchup, the ball’s going to No. 85.” And … “The thing about Antonio was, as great as he was as a player, he was just a regular guy. He was a star, yet he wasn’t too big for the little guys on the team. He’d sit in the cold tub and be there having a conversation with a practice squad tight end and practice squad D-lineman. Gates had a sense of style to him in the clothes he’d wear, the cars he’d drive and how he’d carry himself. He has that great smile. Just in the way he’d carry himself around the facility, his mannerisms, he reminded me of a Michael Jordan or a Kobe Bryant. That’s just the way he operated.”

Upon Gates’ induction into the Hall, it was reported that he is the only one enshrined who never played a down of college football in preparation for his professional career. Gates was a college basketball standout at Kent State (after first attending Michigan State to play football and basketball, but it never happened, then transfering to Eastern Michigan to play basketball, then having to re-establish his academics at College of the Sequoias in Visalia, Calif.) Undrafted in the NFL, the Chargers gave him a $7,000 bonus to sign as a rookie free agent.

Dokie Williams, UCLA (1979 to 1982) and Los Angeles Raiders wide receiver (1983 to 1987):

He took the number left open by Chandler. The Raiders selected Williams in the fifth round of the 1983 NFL Draft. He played in 74 games with 39 starts and caught 148 passes for 2,866 yards and 25 TDs. He also returned 44 kickoffs for 949 yards. He was member of the Raiders Super Bowl XVIII championship team.

Anyone else worth mentioning?

2 thoughts on “Nos. 74, 75, 76 and 85: Merlin Olsen, Deacon Jones, Rosey Grier and Lamar Lundy”