This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 34:

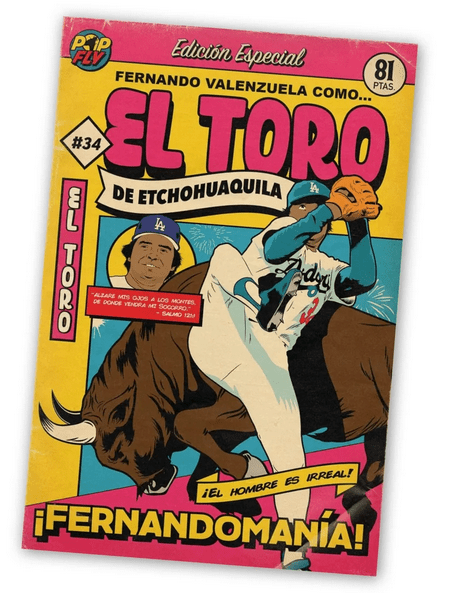

= Fernando Valenzuela, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Shaquille O’Neal, Los Angeles Lakers

= Bo Jackson, Los Angeles Raiders

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 34:

= David Greenwood, Verbum Dei High and UCLA basketball

= Nick Adenhart, Los Angeles Angels

= Paul Pierce, Inglewood High, Los Angeles Clippers

= Paul Cameron, UCLA football

The most interesting story for No. 34:

Fernando Valenzuela, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1980 to 1990)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Dodger Stadium, East L.A., Boyle Heights, Los Feliz, La Canada-Flintridge

On November 1, 2024 — the first of the annual two-day celebration of Dia de la Muertos, a Latino-cultural event where family and friends gathering to pay respects to those close to them who have died — Fernando Valenzuela would have turned 64 years old.

But when he had died nine days earlier, it made that day, and the power of the event, even more poignant.

Valenzuela’s passing from a long bout with liver cancer came just two days before the Los Angeles Dodgers started the 2024 World Series against the New York Yankees. The Dodgers wore No. 34 patches on their shoulder in his honor.

By the time November 1 rolled around, the Dodgers were celebrating a five-game championship series victory, riding double-deck buses through the city. Many players, and fans, wore the familiar Valenzuela 34 jersey.

Also on that day, artist Robert Vargas finished the first of a three-panel project on the side of the Boyle Hotel, facing the First Street on-ramp to Interstate 101 in Boyle Heights. The multifaceted image of Valenzuela seemed to make him come to life again.

Scores of ofrendas poppedup up at the base of site, as well as near the freeway and the street. Same at Dodger Stadium and the roads leading into it.

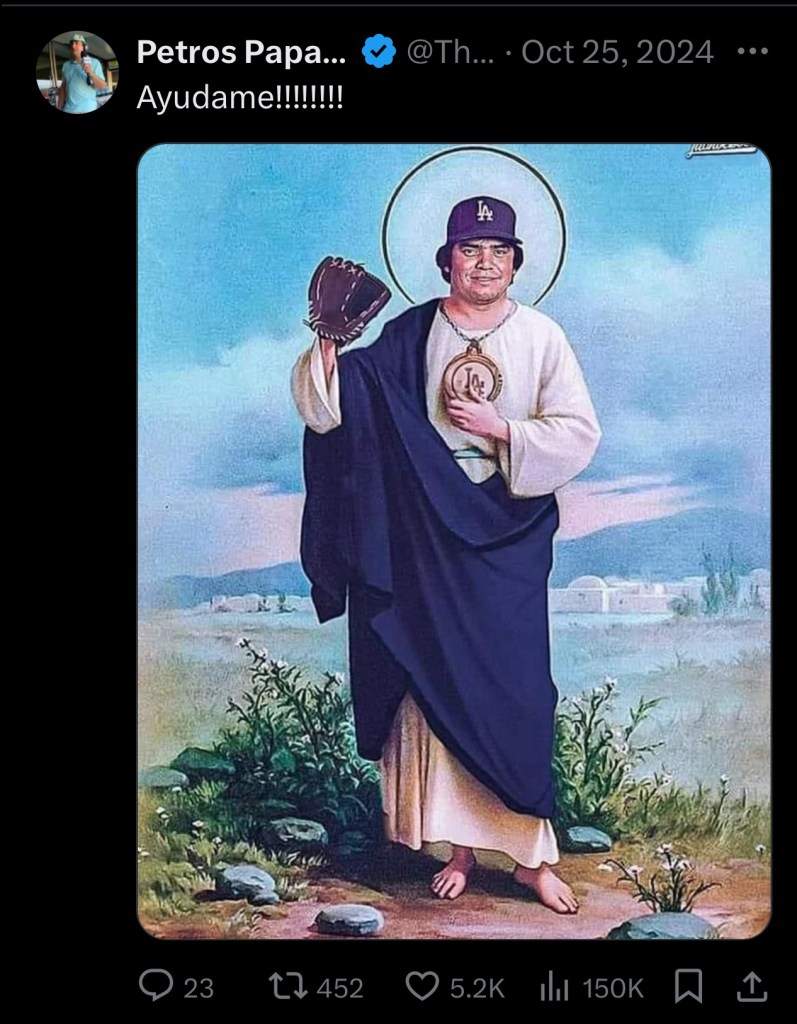

Visiting the mural site almost became going to a religious shrine.

The experience ignited vivid memories of 1981, when fans of all backgrounds swarmed on Dodger Stadium to witness the then-20-year-old from Mexico who only spoke Spanish do things never seen before on a Major League Baseball diamond. Words, in any language, couldn’t describe it.

Especially, as this was happening on the site that once was a dilapidating housing complex for low-income Latino families who unceremoniously were evicted in the late ’50s when the City of L.A. gave the property to the Dodgers to build upon.

At the Vargas mural site, the drone of cars passing by on the freeway provided a constant soundtrack. It was broken up each day Vargas did the mural by a mariachi band, which came from nearby Mariachi Plaza, performed each day at 4 p.m. to give the artistic process a blessing.

“It’s about unity and representation and bringing different cultures together, which Fernando is still doing as we speak,” Vargas told reporters who called him off the scaffolding for interviews.

Boyle Heights born-and-raised, Vargas had, a few months earlier, depicted his vision of newest Dodger star Shohei Ohtani on the side of the Miyako Hotel in Little Tokyo. It was just a mile West of this Valenzuela site, across the bridge that spanned the Los Angeles River. The murals could now serve as cultural touchstones of the city.

As the mural inspired by “Fermandomania” was named “Fernandomania Forever, finished up by early November. To Vargas, and most others who ever saw him play, it reflects an inate feeling that Valenzuela will live forever in the minds of those who still talk about his feats in excited, as well as reverent, tones.

A story in the Wall Street Journal posting in August 2023 read: “Fernando Valenzuela is Forever.”

It was maybe strange for a publication of its nature to post such a story. Did this have to do with money, or how his name, image and likeness were being somehow monetized?

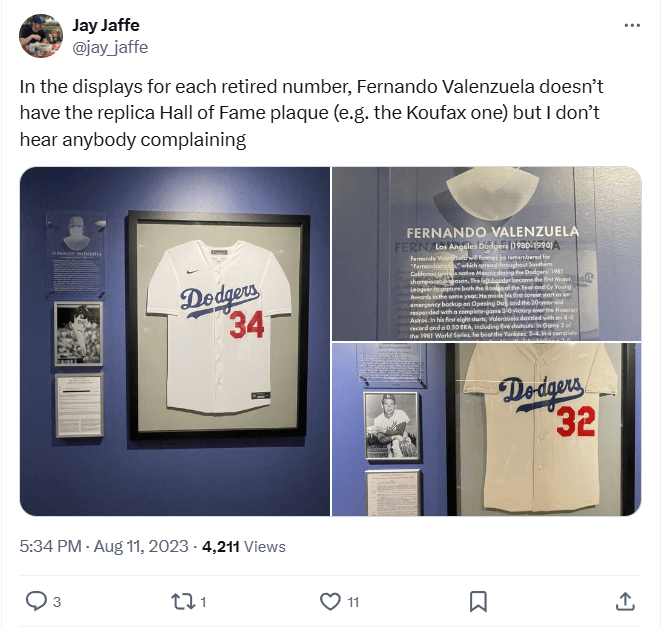

Columnist Jason Gay seized on the opportunity that the Dodgers finally “broke a nearly-airtight tradition” and retired Valenzuela’s No. 34. Club policy at that point had been only players voted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame had could have that kind of statue (except for the exception of taking down the No. 19 worn by longtime player and coach Jim Gilliam, who also died suddenly before a Dodgers-Yankees World Series in 1978 at age 49).

The WSJ piece covered it all.

Valenzuela, the youngest of 12 children in his family from Etchohuaquila in Sonora, Mexico. Playing baseball against his older brothers. A teenager mowing down batters in the Mexican Central League. Discovered by scout Mike Brito, who had gone first to see a shortstop named Ali Uscanga, but then saw Valenzuela pitching in relief, becoming the Mexican League rookie of the year with Leones de Yucatan in 1979.

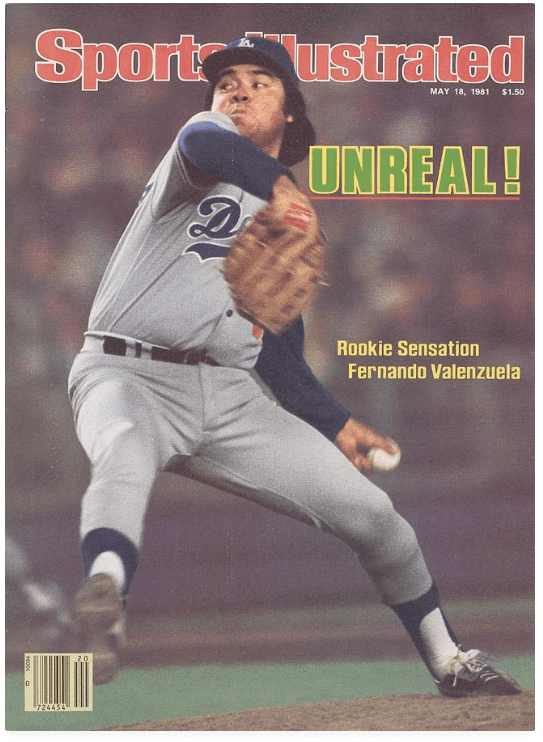

Two years later, when Valenzuela “spellbound the nation” in 1981 when, as a 20-year-old throwing a screwball “that plunged like a rock,” won his first eight starts — five of them shutouts. The 8-0 start to his career bordered on mystical. He only spoke Spanish in public and had this aura around him that kept his language barrier as a way to protect his true identity through enthusiastic interpretations of what he was expressing with an almost deadpan maturity.

That season was interrupted by a 50-day player strike, from June 12 to July 31, but Valenzuela became part of the major draw back to the game for fans who may have been bitter about the stoppage. In a year where he became the first to win the National Rookie of the Year as well as the Cy Young Award, Valenzuela was named starting pitcher for the NL team in the delayed All Star Game when the season resumed, and two champions of each schedule had to play off for the league titles.

Valenzuela’s “unreal” season season was capped by a 147-pitch Game 3 victory at Dodger Stadium on Oct. 23, when he faced 40 batters, walked seven, gave up two homers among the nine hits, but had a complete-game to show for his gutty effort.

He even got a visit at the White House in all that, invited by President Reagan.

All six of his career All Star appearances were with the Dodgers. An improbable no-hitter came against the St. Louis Cardinals at Dodger Stadium on June 29, 1990, ending with Vin Scully imploring fans: “If you have a sombrero, throw it to the sky.”

All this made Valenzuela fell as if he was transcendent. He “changed Los Angeles forever.” He was an heroic figure to immigrants. His success reversed some of the narrative of a tarnished cultural history in the city. For those who worshiped at the altar of baseball, Valenzuela was part of a spiritual journey of remption. His exploits border on biblical.

The star power he created hadn’t been there for Latino fans of that generation, some still smarting from knowing their decedents who were removed by force by officials in a controversial real estate transaction orchestrated by the L.A. City Council.

An intriguing part of Gay’s column was an English-answer, rare Q&A with Valenzuela, who had continued to be a Dodger gem as a Spanish-language broadcaster.

Q: How has this felt like, watching your No. 34 be retired?

It surprised me. But after I stopped using that number, and nobody used it for 32 years, I thought something [might happen]. It made me really happy and my family was so happy, so that was great. It was a good experience.

Q: Anyone old enough to remember can never forget 1981, “Fernandomania,” the craziness of that season. What do you remember most?

Early in my career was not easy, especially when I had to talk to the people in the media. That part was hard for me. But soon I went on the field, I believed in myself, and I tried to do my best.

Q: What’s striking about your early success was that you were so young, but you seemed so confident. Was the pitcher’s mound always a comfortable place for you?

I think so. This game, you have to have confidence. If you don’t, if you don’t know what you have, it won’t help. Every time [I went] to the mound, I wasn’t looking at who I was going to face — I was going to use all my stuff. A lot of people say, “Oh, it’s nice you only had to play every fifth day.” But when I was pitching—that was my day off. I was comfortable. With the fans or the media, it was hard to figure out how to approach them. But when I’m on the mound, I knew what I had to do.

Q: When did you start looking up at the sky in your pitching motion?

I think I did it a little bit in [Double A] San Antonio, Texas League. I thought: “I think that’s going to work, I feel more comfortable when I release the ball.” And I continued to do it that way with the Dodgers.

Q: Is the idea that throws a batter off — or is it just something that helps you focus?

Focus. People ask me about it: “You never look at the plate, how are you going to throw it right?” I say, “Well, before I release the ball, I know.” Mike Scioscia — he was the catcher for most of my games. So if he calls something inside, I focus on the inside of the hitters. I don’t have to look again.

Q: When you are looking skyward, are you looking at anything in particular, or just looking up?

Just looking up, that’s it. Nothing special.

Q: Having the number retired is great, but there are people who think that given your on-field success, and what your career meant for the growth of baseball and its audience, that you should be reconsidered for the Baseball Hall of Fame. What do you think?

Not on my hands. I think it would be nice, but it’s not the main thing for me. If people remember my career, and give me support, that’s the thing for me. If something happened … Cooperstown … (laughs) I’d welcome it. It’d be great, but it’s not one of my goals right now.

Just before the 2023 season, in a book titled “Daybreak at Chavez Ravine: Fernandomania and the Remaking of the Los Angeles Dodgers,” writer Erik Sherman laid out a compelling argument for Valenzuela’s number retirement. It likely helped speed up the process as Dodgers executive received advanced copies of the book in late 2022. They announced at the January 2023 annual fan festival at Dodger Stadium that the number No. 34 would no longer be in circulation — something that had already happened with Valenzuela was released by the team in spring training of 1991.

That piece of news came too late for Sherman to rewrite and update the book. Still, a compelling case was built for why Valenzuela was worthy of a National Baseball Hall of Fame induction discussion — even if he was somewhat dismissed by the baseball writers’ vote in his first two years of eligibility.

Valenzuela’s case included:

= A 36.8 bWAR stat with the Dodgers, and 41.4 bWAR through the end of his MLB career in 1997.

= Leading all Mexican-born pitchers in wins (170), strikeouts (2,074), innings pitched (2,930), shutouts (31), complete games (113) and starts (424). During his 11 seasons with the Dodgers, he put up 141 of those wins against 116 losses with a 3.31 ERA.

= A career 2.00 ERA in eight postseason starts, with a 5-1 record.

Aside from the pivotal Game 3 win World Series win in ’81, Valenzuela won Game 4 of newly-added NL Divisional Series against Houston, a complete-game 2-1 triumph, which helped the Dodgers avoid elimination and set up a Game 5. Valenzuela nine innings in Game 1 of that series but left with the score tied 1-1. Valenzuela also won the decisive Game 5 of the NL Championship Series in Montreal that pushed the Dodgers into the championship round. Valenzuela provided an RBI groundout for the run of a 2-1 win, as the last run came from Rick Monday’s ninth-inning homer. There exists a video of that game in freezing Olympic Stadium, a series already postponed a day because of snow. Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda makes a visit to the mound at one point, and Valenzuela realizes he start blowing fog rings with his breath, which causes him to smile and amuse himself.

= Between 1981 and 1986, Valenzuela was an All-Star every season, posting a 2.97 ERA and averaging 256 innings and 210 strikeouts.

= In Cy Young voting, after he won at age 20, he was third at age 21 in 1982 (a 19-13 mark), fifth at age 24 in 1985 (a 17-10 mark) and second at age 25 in 1986 (a 21-11 mark).

In ’82, he missed out on his 20th win on the last day of the regular season when the Dodgers’ bullpen gave up his lead — that was Joe Morgan’s homer in San Francisco off Terry Forester that knocked the Dodgers out of the playoffs (as the schedule returned to a matchup for the NL title between two vision winners).

In ’86, we was the last pitcher to win 20 games and complete 20 games in a season — including seven of his first 10 starts. In 34 starts, he faced a league-high 1,102 batters, striking our 242 and posting a 5.4 WAR. Houston’s Mike Scott (18-10, 2.22 ERA, 306 strikeouts, 8.4 WAR) aced him out for the Cy Young. It among the greatest seasons in Dodgers pitching history. Dodgers team historian Mark Langill, in a story for Dodgers Insider 2023, called it “a hidden gem, lost in a quiet summer devoid of a pennant race.” Valenzuela won 21 games on a team that posted a 73-89 record, the lowest win total in a full season since 1967, finishing 23 games out of first, avoiding last place by a half game.

= From 1982 and 1987, he completed 85 of 209 starts.

= Name the National League pitcher who, over the last 100 years, had the most shutouts recorded by age 25: a) Tom Seaver; b) Don Drysdale; c) Dizzy Dean; d) Juan Marichal; e) Fernando Valenzuela. You know the answer.

= In the 1986 All Star Game in Houston, Valenzuela struck out Don Mattingly, Cal Ripken Jr. (looking), Jesse Barfield (looking), Lou Whitaker (looking) and Ted Higuera in succession before Kirby Puckett grounded out. The five straight Ks tied a record set by Carl Hubbell. Valenzuela pitched the fourth, fifth and sixth inning of that game after starter Dwight Gooden, giving up just one hit and no runs, facing 10 batters.

= 1988: He received a ring for being on that Dodgers’ World Series roster but injured during the playoffs (he was 5-8 in 23 starts, including three complete games). He was basically shut down at the end of July but came back to pitch on Sept. 26 at San Diego and Oct. 1 vs. San Francisco to see if he could be ready for the post-season. Against the Padres, he went three innings and faced 14 batters. Against the Giants, on the last day of the regular season, he threw four innings in relief and got a save, giving up one unearned run, which denied Rick Reuschel of his 20th win.

= 1989: He played first base. The Dodgers and Astros remained tied in the 21st inning of a game at the Astrodome. The Dodgers were out of position players. So Valenzuela played first base, Eddie Murray was moved to third base, and third baseman Jeff Hamilton came into pitch. Valenzuela recorded two putouts at first, but a Rafael Ramirez line drive in the bottom of the 22nd sailed just over Valenzuela’s glove for a walk-off Astros win.

= 1996: A comeback with the San Diego Padres produced a 13-8 record in 171 innings with a 3.62 ERA at age 35 as they won the NL West.

= In 1981 and ’83, Valenzuela also won a Silver Slugger Award as the league’s best hitter at his position (a .250 average in his rookie year with just nine strikeouts in 64 at bats — he also hit a triple came in a game against St. Louis while he threw a complete-game shutout). In 1990, he hit .304 in 78 at bats with five doubles, a home run and career-best 11 RBIs. The Dodgers issued a Valenzuela bobblehead in 2015 depicting him batting.

A run-scoring hits in his second start of the 1981 season even got Scully looking for a way to describe the delirium.

“I swear Fernando – you are too much in any language. Can you imagine on this night of all nights, he’s 2-for-2 … he got the first Dodger hit … he drives in a run and the Dodgers lead, 1-0. … Listen to this crowd just talking to themselves … What a show … Dodger Stadium, what a great place to be!”

The highest Valenzuela came in the Baseball Writers Association of America vote for the Hall of Fame was a meager 6.2 percent. A case was made for his induction by the Los Angeles Times’ Dylan Hernandez in 2021, by the Times’ Jorge Castillo in 2023 and by the Times’ Gustavo Arellano in reflecting on Valenzuela’s passing in 2024. Jaime Jarrin, the Dodgers’ Hall of Fame Spanish-language broadcaster, a Hall of Fame special committee voter on occasion, and companion of Valenzuela in the broadcast booth when the pitcher came back in 2003 to add his voice, said of Valenzuela:

“I sincerely believe Fernando should have been voted into the Hall of Fame for one simple reason: In the creed of the Hall of Fame, it asks what have you done for baseball. And I believe that there is no player who has done more for the good of baseball than Fernando Valenzuela.”

In the winter of 2025, the Contemporary Baseball Era Committee finally included Valenzuela in a list of 12 candidates to consider. This is the Hall’s oversight committed. The Times’ Bill Shaikin made another Valenzuela induction case as did MLB.com’s Manny Randhawa.

Still, Valenzuela did not get enough of the 16 people on the committee to vote him in with what was a rather hefty group to consider. Since he received fewer than five votes from that group, he won’t be back on the committee’s ballot in the 2028 cycle, and the next time the committee could review his case won’t be until 2031.

Sure, the Baseball Hall of Fame has done its own tribute stories. It erected a “Fernandomania” exhibit where it could display the items it has in its collection — including a 2001 stadium give-away bobblehead that he signed.

A number of other Halls of Fame have recognized Valenzuela’s impact, such as the California Sports Hall of Fame. The Navajoa, Mexico, native is a member of the Hispanic Heritage Baseball Museum Hall of Fame and the Caribbean Baseball Hall of Fame.

His No. 34 was also, in 2019, retired by the entire Mexican Baseball League, five years before the Dodgers finally did the same thing for its franchise. Only Jackie Robinson’s No. 42, Wayne Gretzky’s No. 99 and Bill Russell’s No. 6 are the only league-wide numbers retired.

In 2006, the Pasadena-based Baseball Reliquary had the voters of its Shrine of the Eternals make Valenzuela worthy of entry after six years on its ballot. Former teammate Bobby Castillo acceptd the induction on behalf of Valenzuela, who was doing the Dodgers’ Spanish-language radio broadcast that afternoon.

Castillo, a former relief pitcher who died in 2014 and was credited with teaching Valenzuela the screwball, elicited laughter from the audience when he remarked: “I’m still finishing up for him.”

The team tried to create something special when they made him part of its first “Legends of Dodger Baseball” induction in 2018 (with Steve Garvey and Don Newcomb) when it appeared the Baseball Hall of Fame wasn’t going to happen anytime soon for any of them.

In 2023, the City of Los Angeles issued a proclamation declaring Aug. 11 as “Fernando Valenzuela Day” when the Dodgers retired his number.

Yet, to Dodgers fans, every day was Fernando Day when he was seen at the ballpark, coming or going to the broadcast booth, hanging out on the concourse, playing golf, or on the field for another first-pitch ceremony.

Maybe El Toro will never be granted a Cooperstown bronze. Voting him in now, after his passing, might even seem like an empty gesture. It doesn’t make him less immortal. Maybe even more so.

Valenzuela’s legacy is also in the family he has left behind: Wife Linda, who he married in that magical 1981 year, helped him raise their kids in a home based in the Los Feliz area of Los Angeles not far from Dodger Stadium. They had four children and seven grandchildren.

Fernando Valenzuela Jr., born in 1992, was an All-Mission League first baseman at St. Francis High in La Canada Flintridge, hitting .450 in his career. He went onto Glendale Community College (All-Western State Conference for two years, hitting .390) and the University of Nevada-Las Vegas (a team-leading .337 average and Mountain West Conference Player of the Year). He was in the San Diego Padres and Chicago White Sox organization and went to Triple-A with several Mexican League teams as well through 2015.

At his father’s funeral Mass at the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels in downtown, Fernando Jr. said: “I want to be a good man, a good father and a good son like he was. I want to be like Fernando Valenzuela.”

Valenzuela’s son Ricardo, born in 1984, was also an offensive lineman on the St. Francis football team. He went on to be the general manager of Tigres de Quintana Roo — a Mexican League team owned by Valenzuela and his wife. Fernando Jr. is the team president.

Daughers Linda (1986) and and Maria (1991) also came into the Valenzuela family.

At the funeral, The Rev. James Anguiano, moderator of the Curia and vicar general of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, delivered a homily in Spanish and English and admitted: “Today I wanted to wear my No. 34 jersey, but I don’t think I could fit it under what I’m wearing.”

The family returned for the ceremonial first pitch ceremony at the 2024 World Series Game 1 at Dodger Stadium, where previously announced honorees Orel Hershiser and Steve Yeager wore No. 34 jerseys, placed the ball on the empty mound, and had a moment of silence with the Dodger Stadium flag as half staff.

“I think if there’s two people that probably impacted this organization most,’’ Dodgers manager Dave Roberts said that day, “I think you would say Jackie Robinson and Fernando Valenzuela. No disrespect to anyone else, but if you’re talking about currently the fan base, there’s a lot of people that are here and support the Dodgers south of the border because of Fernando. His legacy continues to live on. He was a friend of mine. And so to not see him up in the (broadcast) booth or to say hello, is sad for me and his family. Fernando was a gentleman, a great Dodger, and what a humble man.’’

Fans are already petitioning to have a statue of Valenzuela somewhere at Dodger Stadium along with Sandy Koufax and Jackie Robinson.

Why not?

In Jon Weisman’s 2018 book, “Brothers in Arms: Koufax, Kershaw, and the Dodgers’ Extraordinary Pitching Tradition,” the chapter on Valenzuela offers a reminder about how close the Dodgers battled against the Yankees for his rights.

The Dodgers finally got the 18-year-old from his Mexican League team in July 1979 for a reported $120,000. Of that, $20,000 went to him, which gave to his family.

The chapter concluded a comparison of Valenzuela and Koufax, as they shared a common age when their time was up as a Dodger:

In his Dodger career, Valenzuela threw 2,348⅔ innings (seventh in team history) with a 3.31 ERA (107 ERA+), 1,759 strikeouts (sixth in Dodger history), 915 walks (second, behind Don Sutton), 107 complete games (11th) and 29 shutouts (tied with Dazzy Vance for sixth).

Valenzuela was 30 years old, the same age of Koufax when he threw his last pitch as a Dodger. But Valenzuela continued for six more years. His initial comeback attempt, with the nearby Angels in 1991, generated much attention but lasted only two big-league starts, and he didn’t pitch in the majors at all in 1992. However, coming back yet again in 1993, this time with Baltimore, he threw 178⅔ innings in 31 starts. He remained inconsistent, as a 4.91 ERA (91 ERA+) signaled, but had several strong performances, including a six-hit shutout three years and a day after his Dodger no-hitter. With San Diego in 1996, he threw 171⅔ innings with a 3.62 ERA (110 ERA+).

His major-league career finally ended on July 14, 1997 with St. Louis, though as late as 2006, at age 46, he made 11 starts for Mexicali in the Mexican Winter League.

Moving on to become a Dodger broadcaster, Valenzuela professes to like all sports, but his love for baseball never wavered.

“It’s almost – I don’t want to say perfect – it’s almost a perfect game,” Valenzuela says.

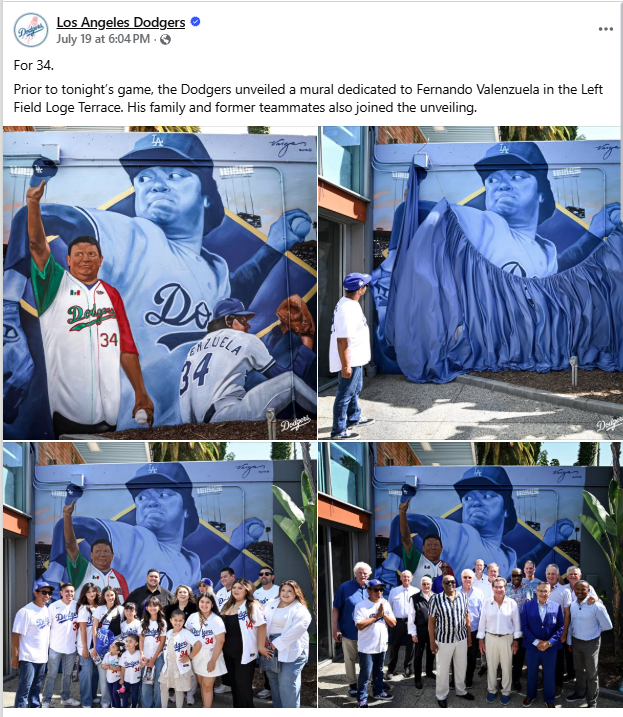

The Dodgers commissioned a mural of Valenzuela at Dodger Stadium in the left-field loge area, unveiled in July of 2025. Again, Robert Vargas was the artist asked to do it. It adds to the list of Valenzuela murals around the city.

In a 2023 edition of Dodger Insider, Valenzuela was asked if he considered what he did on the mound very heroic?

“Heroes are in cartoons or something like that,” he said. “I think the ones who are heroes are people who rescue people. If the little things I did in baseball helped people, if it helped them never giving up, keep continuing, helped them think you can do anything, that makes me proud.”

Let’s leave what Joe Posnanski wrote on his Substack account on Oct 23, 2024 after Valenzuela died:

There’s a baseball statistic I have been working on called JAR. It stands for “Joy Above Replacement.” For a time, I called it HAR (Happiness Above Replacement) and DAR (Delight Above Replacement), and even FAR.

The last stands for Fernando Above Replacement.

I honestly believe that Fernando Valenzuela, inning for inning, brought more glee, more laughter, more euphoria, more bliss and more happy feelings than any player in baseball history. To watch him pitch was to smile. The watch him hit was to feel a little more alive. To see him unwind his body as only he did—always pausing for an instant to look up to the sky as if he were asking God: “Are you watching this?”—and then uncork that magnificent screwball that had a mind of its own and to watch hitters helpless against its power, all of it took all of us one step closer to heaven. …

He was the people’s pitcher, a long-haired, pudgy lefty from Etchohuaquila who became a star and brought baseball fans more Joy Above Replacement than anyone. He made us all believe that if we, too, could just find a screwball, maybe, just maybe, we could strike out the world.

More to read on the life and times of Fernando Valenzuela:

= The 2010 ESPN “30 for 30” piece called“Fernando Nation” is on demand

= The Society of American Baseball Researchers biography on Fernando Valenzuela Anguame has not posted, but an historic recap of “Fernandomania” is logged here by Vic Wilson.

= When Valenzuela gravitated to the California Angels in attempt to show Southern California he could still pitch, No. 34 was already being worn by relief pitcher Bryan Harvey (1988 to ’92), so Valenzuela had to wear No. 36 in ’92. Valenzuela reclaimed No. 34 with Baltimore (1993), San Diego (1995 to ’97) and St. Louis (’97), but took No. 33 with Philadelphia (’94).

Who else wore No. 34 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

Shaquille O’Neal, Los Angeles Lakers center (1996-97 to 2003-04):

When Lakers GM Jerry West pulled off the signing of free-agent Shaquille O’Neal, bringing him to L.A. after his first four seasons in Orlando, there was the situation where the No. 32 that Shaq wore to that point in the NBA wasn’t available in L.A. It had been retired for Magic Johnson. He could have switched to No. 33. It had already been retired for Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. So the 7-foot-1, 325-pounder who had created nicknames for himself such as The Big Aristotle, Superman or Shaq Fu, assumed No. 34, which he did not wear with any other team in his 19-year pro career, but only during the eight he spent as a Laker. In that time, he won three NBA titles, made seven All Star teams and captured his only regular season MVP trophy (1999-2000 when he averaged a league-best and career-high 29.7 points a game and a career-best 13.6 rebounds a game at age 27). O’Neal’s career-best 61-point game, in March of 2000, came against the rival Los Angeles Clippers on his 28th birthday.

Not including endorsements, O’Neal’s financial haul exceeded $144 million from his time with the Lakers. It also reflected the value he brought as a force to be reckoned with, especially in oft-played playoff series against Sacramento and Portland. In a franchise that had a big men legacy of George Mikan, Wilt Chamberlain and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, O’Neal may have made it to the Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield, Mass., but he wasn’t always up to that lofty sort of status among the franchise fans. You were either a “Shaq guy” or a “Kobe guy” as it turned out when the two were on the roster together. In the end, the longstanding rift with Kobe Bryant forced Shaq’s departure after winning his third NBA Final MVP Awards. Bryant stayed. Yet when O’Neal’s statue was unveiled in front of Staples Center in 2017, Bryant called him “the most dominant player I’ve ever seen.”

Bo Jackson, Los Angeles Raiders running back (1987 to 1990):

The professional chapters of Vincent Edward “Bo” Jackson’s two-sport All Star abilities started and ended in Southern California. The Los Angeles Raiders allowed him to have a “hobby” as an NFL running back starting with the 1987 season, which seemed ridiculous at a time he was trying to make a career for himself playing professional baseball with the MLB’s Kansas City Royals. The only player in NFL history to record two runs in excess of 90 yards, Jackson played 38 games in four seasons, able to join the Raiders only in October after the Royals’ baseball season was over. His stats show he had 515 carries for 2,782 yards, averaging of 5.4 yards per carry.

In his 2022 New York Times bestseller, “The Last Folk Hero: The Life and Myth of Bo Jackson,” Jeff Pearlman excerpted various newspaper writers’ quotes trying to size up what Jackson meant in the SoCal sports landscape, which ended when the California Angels became the last stop of his pro baseball career in 1994, where he hit his final home run. That’s when the MLB season stopped for labor issues. Jackson stopped playing as well.

In the 1989 NFL season, The Los Angeles Times’ Jim Murray wrote: “The team is just kind of an afterthought when Bo Jackson comes to town. Bo and the Ten Dwarfs. The hotel lobbies are jammed with people hoping not to see the Los Angeles Raiders but to get a glimpse of Bo Jackson. It’s like a John Wayne movie, a Caruso opera. The rest of the cast is unimportant.”

Steve Bishoff of the Orange County Register: “(Bo Jackson) is the best I’ve ever seen. The finest athlete of our time. No, make that of any time. Jim Thorpe, Jackie Robinson, Jim Brown and anyone else people care to mention in the same breath now have to be brushed aside. Next to Bo, they all seem to be playing in slo-mo. Bo Jackson belongs on his own pedestal. Don’t put him in the Hall of Fame. Put him in the Louvre.”

The 6-foot-1, 227-pounder out of the University of Auburn really fell into the Raiders’ lap because a) he insisted he would never play for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, who took him No. 1 overall in the 1986 NFL Draft but messed up his college baseball eligibility in the process and b) the Raiders rolled the dice and drafted him in 1987 in the seventh round, No. 183 overall, just in case.

Jackson’s intent was to focus just on baseball with the Kansas City Royals (wearing No. 16 after wearing No. 29 for Auburn’s baseball program). In 1989, after hitting 32 homers and driving in 105 runs for the Royals, he waited 10 days after the MLB season ended, then joined the Raiders and ran for 950 yards in just 11 games.

Another part of Jackson’s legend: His statue in the video game world thanks to Tecmo Super Bowl:

After he retired from football because of the displaced hip he suffered, one may have wondered what happened to his final Raiders’ No. 34 jersey. For some reason, it’s in the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Here’s how:

In the midst of Jackson’s national popularity as a baseball player, Cooperstown’s caretakers asked the Raiders for an artifact donation. The football team sent in early 1991 a Raiders signature silver-and-black football jersey, and the Hall sent a letter to Raiders executive assistant Al LoCasale, dated March 4, 1991: “On behalf of the staff of the Baseball Hall of Fame & Museum I wish to thank you for sending along the #34 jersey worn by Bo Jackson, to be used in our ‘Today’s Stars’ exhibit in the museum. It was 30 years later when Hall of Fame senior curator Tom Shieber was researching the jersey for potential use in a YouTube series called “Hall of Fame Connections.”

“I am certain that this is the very jersey Bo wore in the 1990 AFC Divisional Playoff game of Jan. 13, 1991, in which the Raiders beat the Bengals, 20-10, at the Los Angeles Coliseum,” Shieber said. “This was the game in which Bo seriously injured his hip and, alas, was the last NFL game Jackson ever played. As far as I can tell, it is the only jersey he wore during that game.”

Jackson once said about his career: “There’s no reason for anyone to feel sorry for what happened to me, or what might have been. I didn’t play sports to make it to the Hall of Fame. I just played for the love of sport. I can probably say, if I wanted to be in the Baseball Hall of Fame, I could have been easily. If I wanted to be in the (Pro) Football Hall of Fame, I could have done that too. But I can say also that I wouldn’t go back and change a thing.”

Paul Pierce, Inglewood High guard (1994 to 1995); Los Angeles Clippers guard (2015-16 to 2016-17):

Keeping the number he had since his prep days, Pierce ended up picking the Clippers over the Lakers when it was time to mop up his his NBA career because — The Truth be told — all those years as a Boston Celtics star made him never wanting to wear purple and gold. Instead of retiring as a full-time Celtic after his 10th All-Star season over an 11-year period, and drawing nearly $190 million in salary, Pierce, who also wore No. 34 in his three years at the University of Kansas, decided to stretch things out. He wasn’t ready to sit. So after mediocre seasons in Brooklyn and Washington, he got Clippers coach Doc Rivers (who coached for nine of his 15 seasons in Boston) to add him to the roster. And so he signed a multi-year deal, got $3.4 million for each of the two seasons he played, another $1 mil for the 2017-18 season he didn’t play, was waved by the Clippers, signed a ceremonial contract with the Celtics and retired as a shamrock. “It’s great to be home, to have an opportunity to play in front of family and friends, to have an opportunity to win a championship,” he said on the day he signed with the Clippers. In high school, failing to make the varsity team as a freshman and sophomore, Pierce finished his senior season averaging 27 points and 11 assists a game to be California’s Mr. Basketball and a McDonald’s All-American.

Paul Cameron, UCLA football tailback/defensive back (1951 to 1953):

A charter member of the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 1984, Paul Cameron was finally inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 2024 — just months after he died at age 91. More than 50 years earlier, the former Burbank High star was third in the 1953 Heisman Trophy voting, having finished sixth as a junior. One of the last great Single-Wing triple-threat tailbacks as a runner, passer and punter, Cameron amassed 3,332 yards of total offense during his career, with 1,451 yards and 19 touchdowns as a runner. He passed for 1,881 yards and 25 touchdowns, setting seven school records, including most career touchdown passes (25), most total offense (3,332 yards) and most career touchdowns (44). Leading the conference in scoring with 12 touchdowns in 1953 as well as rushing with 134 carries for 672 yards, he already led the conference in total offense in ’51, rushing for 597 yards and passing for another 855 for a total of 1,428 yards. On special teams, he returned nine kickoffs, averaging 20.2 yards per return, and he averaged 13.1 yards on 23 punt returns. He also punted, averaging 41.3 yards per punt in 1953, placing him third in the nation. On the opposite of the ball, he played defensive back, leading the Bruins with four interceptions in 1953. UCLA went 21-6-1 during his three seasons in Westwood, including winning the Pacific Coast Conference in 1953 and appearing in the Rose Bowl against Michigan State. His No. 34 UCLA jersey has been retired.

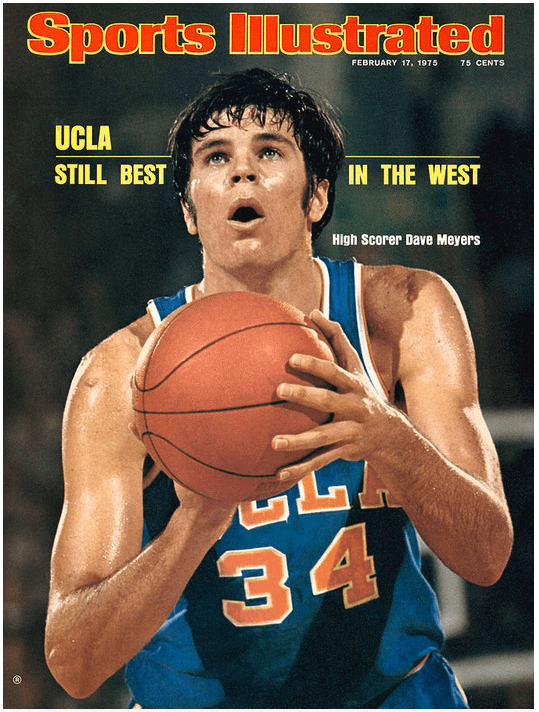

David Meyers, UCLA basketball forward (1972-73 to 1974-75):

The All-American forward out of Sonora High in La Habra — an older brother of UCLA women’s basketball star Ann Meyers and was one of 11 children in his family — David Meyers was the team MVP as a senior forward leading the Bruins with 18.3 points and 7.9 rebounds a game during the program’s 10th title in a 12-year span and sporting a 28-3 record the year after Bill Walton and Keith Wilkes graduated. Meyers had 24 points and 11 rebounds in the Bruins’ title game win over Kentucky. The No. 2 overall pick by the Los Angeles Lakers in the 1975 NBA Draft behind North Carolina State’s David Thompson, Meyers never got to play for his hometown team as he was sent as part of a package deal to Milwaukee for Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, lasting four NBA seasons with the Bucks before retiring with back issues.

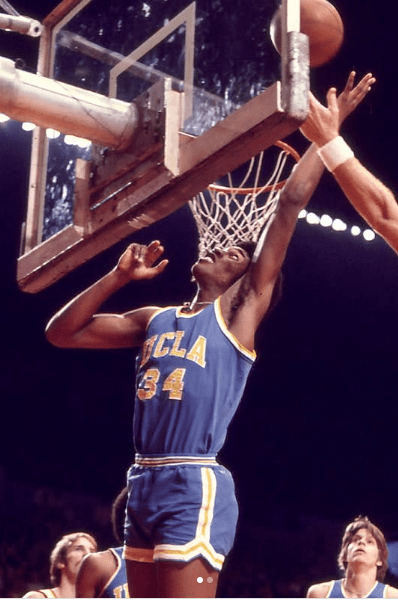

David Greenwood, Verbum Dei High basketball (1970-71 to 1974-75); UCLA basketball forward (1975-76 to 1978-79):

On one of the greatest All-CIF teams in Southern California history, the 6-foot-10, 212-pound Greenwood stood out as the best for his performance at Verbum Dei High in Watts. Born in Lynwood, Greenwood averaged 21 points a game as a senior for a team that lost the CIF 4-A playoffs to Palos Verdes in the semifinals. Verbum Dei had won 39 in a row before losing that contest. He would return as the head coach at his alma mate, guiding Verbum Dei to state championships in 1998 and 1999. His induction into the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 1997 was based on the two-time All-American leading the Bruins in scoring (17.5 and 19.9 points) and rebounding (11.4 and 10.3) in his junior and senior seasons. The ’77-’78 and ’78-’79 teams that won the Pac-8 and Pac-10 titles under Gary Cunningham both finished ranked No. 2 in the final AP polls — the Bruins lost to Arkansas in the second round of the ’78 NCAA Tournament and lost to DePaul in the third round of the ’79 Tournament. “He told me if I went to USC or UNLV or Notre Dame, I’d be an All-American,” Greenwood once told The L.A. Times about why he believed in John Wooden’s recruitment of him. “But if I went to UCLA, I’d be able to test myself against 12 other high school All-Americans every single day. … It was kind of like, ‘Come here and test your mettle.’ ” Greenwood remains No. 15 on the school’s all-time scoring list with 1,721 points. He became was the second pick of the 1979 NBA Draft by Chicago, right after the Lakers choose Magic Johnson at No. 1. Greenwood died at 68 in 2025.

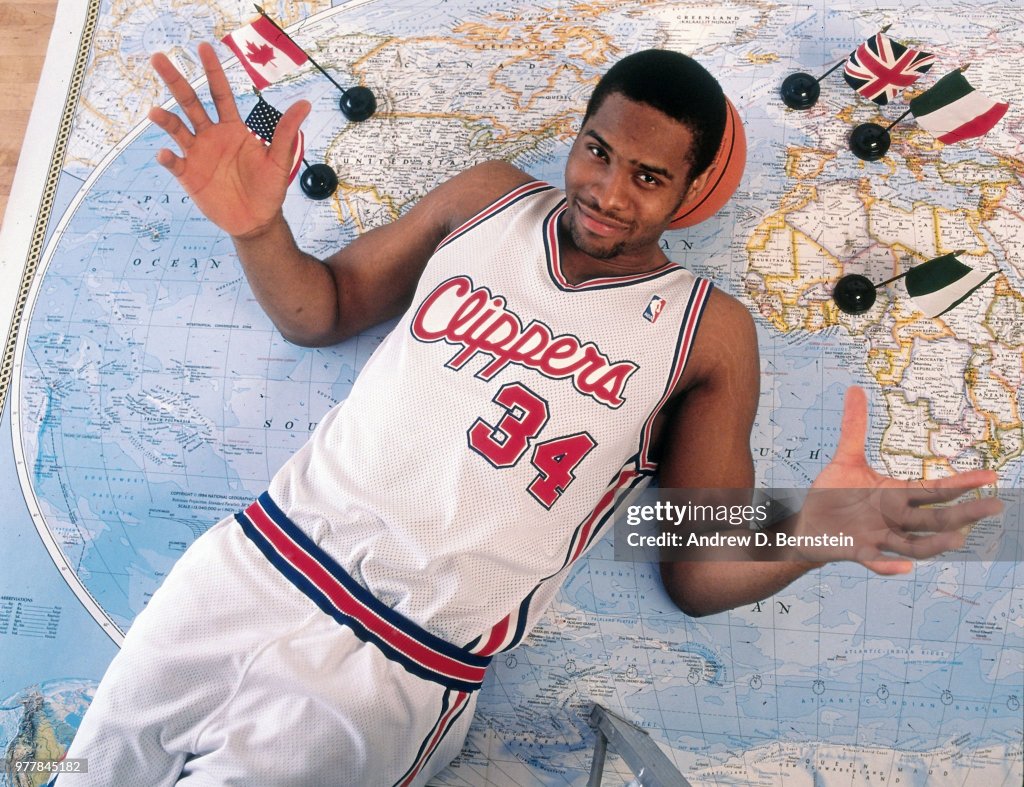

Michael Olowokandi, Los Angeles Clippers (1998-99 to 2002-03):

Born in Nigeria, raised in London, and, according to legend, opened a Peterson’s Guide to American Colleges and Universities on his 20th birthday and randomly picked the University of the Pacific to inquire about a basketball scholarship, Olowokandi was the No. 1 overall pick in the 1998 NBA Draft. The Clippers passed over future Hall of Famers Paul Pierce, Vince Carter and Dirk Nowitzki to get “The Kandi Man,” who some scouts believed would be the next Hakeem Olajuwon. Olowokandi set records during his NBA pre-draft workouts, running the 40-yard dash in 4.55 seconds. Some of the team officials wanted to take guard Mike Bibby, but Clippers GM Elgin Baylor insisted on Olowkandi. Five seasons in, after a series of knee issues and coaching clashes, the best he could produce was seventh in the voting of Most Improved Player in 2002. Allowed to go free to Minnesota, Olowokandi somehow played in exactly 500 NBA regular-season games and had a 2.5 Win Shares, as well as a minus-8.5 in Value over Replacement Player. That last stat is the worst mark of anyone in the ’98 draft. Olowokandi averaged 9.9 points, 8.0 rebounds and 1.6 blocks in his 323 games played with the Clippers over five seasons. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, an assistant coach for the Clippers during Olowokandi’s time, called him “talented but uncoachable” and cited his lack of willingness to accept criticism in practice as his biggest hurdle. In his book, “Got Your Answers: The 100 Greatest Sports Arguments Settled,” ESPN’s Mike Greenberg called the Olowokandi-Clippers deal the “worst No. 1 overall pick in the NBA Draft” and a “sheer disaster.”

Ken Brett, California Angels pitcher (1977 to 1978), Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1979):

This is his trivia connection: Who was the last Dodger to wear No. 34 before Fernando Valenzuela? George Brett’s older brother. And he was a left-handed pitcher who could handle himself just fine at the plate with a bat in his hand. The former El Segundo High star (who wore No. 6 as an Eagle during his sophomore year than then No. 7 as a junior and senior) started on the roster of the Boston Red Sox and was pitching in the 1967 World Series as a teenager just months after his high-school graduation – the youngest pitcher to ever appear in a championship series. His journey through 10 MLB teams ended with Kansas City, playing as George’s teammate. As a hitter, Brett excelled to the point where Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda (and former team scout) once said of him: “If we’d drafted him, we’d have put him in center field and he’d have stayed there.” Longtime scout Joe Stephenson once called him “a combination of George Brett, Fred Lynn, and Roger Maris. He was the best prospect that I ever saw.” When he was named the Daily Breeze Baseball Player of the Year in 1966, it was based on a 6-1 record on the mound in league play, 5-0 in the playoffs, and .484 batting average with eight homers. In the first round, he no-hit Rancho Alamitos, striking out 11, and drove in all three runs with a third-inning homer, going 2-for-3 with a triple. He was also the 1965 CIF-SS 2A Player of the Year as a junior when he single-handedly took El Segundo to the title pitching every inning of every playoff game, striking our 42 in the four wins. After his MLB career, Brett was a TV broadcaster for the Angels for eight seasons.

Elvis Peacock, Los Angeles Rams running back (1978 to 1980): The name alone gets him a place on any list of anything relevant. The Rams took Elvis Zaring Peacock (his full name) No. 20 overall in the 1978 NFL draft out of Oklahoma’s Wishbone offense (and winning two national titles). The 6-foot-1, 212-pounder was the third running back taken in the draft and came at a time when the Rams felt they needed to prepare for the departure of Lawrence McCutchen as the main ball carrier. Peacock, injured his entire rookie season, was a backup in ’79 (the year the Rams went to the Super Bowl) and then started nine of 13 games in 1980 and was second on the team with nine touchdowns rushing and receiving combined. But the Rams dealt him to Cincinnati, where he lasted just one more year, was done by age 25 and rarely spoke about his NFL playing days — even his son didn’t know about his father’s career until later in life.

John Block, Los Angeles Lakers center (1966-67): The 6-foot-9 power forward/center from Glendale High and Glendale Community College set USC’s single-game scoring record with 45 points against Washington in 1966 and, with another 44 point game against Oregon, establish a school record with a 25.2 points per game mark as a season. That led the AAWU, as well as his 10.8 rebounds a game. The Lakers made him a third-round pick (27th overall) in the 1966 NBA draft but he would be snatched up by the expansion San Diego Rockets a year later and go on to have a 10-year NBA career and one All-Star selection. In three seasons and 78 games with USC (1963-64 to 1965-66) he averaged 18.2 points and 9.3 rebounds

Have you heard this story:

Andy Reid, NFL “Punt Pass and Kick” competitor, Los Angeles Rams representative (1971):

The video evidence that shows the future Super Bowl-winning head coach, at age 13 and wearing a No. 34 Les Josephson-style (and sized appropriately) Los Angeles Rams jersey to represent his home team during a nationally televised punt, pass and kick event at the Los Angeles Coliseum in 1971, pretty much is self explanatory. Graphic misspellings and all. This was before he attended and was Big Man On Campus at L.A.’s Marshall High (wearing No. 76) and worked at Dodger Stadium as a vendor. And here’s all one may need to explore this story even further. And, this story from Sports Illustrated. Apparently, the only evidence that remains from that Punt, Pass, and Kick competition is that brief video clip that TV producers like to pull up from time to time. Josephson was a Los Angeles Rams running back from 1964 to 1974.

Nick Adenhart, Los Angeles Angels pitcher (2008 to 2009):

Just hours after pitching six shutout innings his first start of the ’09 season, on April 9, the 22-year-old was killed in a car collision with a drunk driver. The Angels suspended their next three games and the team would honor him as it won the 2009 American League West division title by keeping his jersey in the dugout and a logo on the outfield fence at Angel Stadium. When the Angels picked up Noah Syndergaard prior to the 2022 season, the team was given the OK to give him the No. 34 he wore with the New York Mets. But when Syndergaard ended up for less than a season with the Los Angeles Dodgers, there was no way he would get No. 34 again.

Bobby Darwin, Los Angeles Angels pitcher (1962), Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (1969 to 1971):

Out of Los Angeles Jordan High, Darwin wore No. 34 when he made his major-league debut as a 19-year-old pitcher with the Angels on Sept. 30, 1962, coming up from the California Leagues team in San Jose (where he was 11-6 with a 4.12 ERA in 24 starts). He gave up four runs, eight hits, four walks and striking out six in 3 1/3 innings to take a loss at Cleveland. It wasn’t until 1972 that he exceeded his classification as a rookie, because for the next 10 years, he kept pitching in the minor leagues, going to Baltimore’s organization (1963 to ’68) and then came to his hometown Dodgers in the Rule 5 draft. In 1969, the Dodgers also gave him No. 34 and had him pitch in three games in April, going three innings. His last major-league batter: Getting Henry Aaron to ground out. That’s when he was converted to a right fielder, first at Single-A Bakersfield, where he hit 23 homers and drove 70 runs with 10 stolen bases, hitting .297. By age 28, he was a Triple-A Spokane and hitting .293 when the Dodgers called him up in September, ’71 for 11 games. Wearing No. 35, Darwin hit his first major-league homer, a pinch-hit three-run homer against Chicago at Dodger Stadium on July 7 in a Dodgers’ 4-3 loss. But the next season, Darwin was traded to Minnesota for backup catcher Paul Powell. Darwin had seasons of 22, 18 and 25 home runs for the Twins, with RBIs of 80, 90 and 94, but he was also leading the AL in striking out three straight seasons. He went to Milwaukee, Boston and the Chicago Cubs before he was out of the big leagues, playing one more year in Mexico. He came back to the Dodgers as a long-time scout starting in 1983 and was honored by the team for his service in 2010.

Stan Love, Los Angeles Lakers forward (1973-74 to 1974-75):

The 6-foot-9 power forward out of the University of Oregon had SoCal roots — Morningside High in Inglewood. He has soul — the younger brother of Mike Love, lead singer of The Beach Boys, and a cousin of Brian, Carl and Dennis Wilson. He had a legacy — the father of NBA star Kevin Love, who spent a year at UCLA and wore No. 42 in honor of the fact that his dad, Stan, was a teammate of Connie Hawkins in his brief season-and-a-half with the rebuilding Lakers under coach Bill Sharman, coming off the 1972 NBA title and before Kareem Abdul-Jabbar arrived. Love started a game for the Lakers in December of ’73 and had 21 points, 12 rebounds, six assists and two steals in 42 minutes during in a 17-point win over Phoenix at the Forum, holding his own with Lakers teammates Hawkins, Jerry West and Gail Goodrich. When Love died on April 27, 2025, his son Kevin posted on Instagram: “You have undoubtedly been my greatest teacher. … You taught me admirable qualities like respect & kindness. Humor & wit. Ambition & work ethic. Grit & aggressive will. The insight that failure brings. And that time is our most precious commodity.” After Stan Love’s pro career ended, he moved back to Southern California, toured the world with the Beach Boys and served as the band’s bodyguard, looking after cousin Brian Wilson as Wilson battled drug addiction.

Bob Sprout, California Angels pitcher (1961): The left-hander’s one and only MLB appearance sprouted at Wrigley Field in L.A., given a start against Washington as a 19-year-old in late September call-up (along with Dallas/Fort Worth teammates Jim Fergosi and Dean Chance) with five games left in the team’s inaugural season. He went the first four inning, facing 18 batters, giving up two earned runs and leading 4-3 when he came out in an eventual 8-6 win against the Senators. The Angels had taken him off the Detroit roster in the expansion draft. He came with credentials — with the Tigers’ Class-D Decatur Commodores, Sprout struck out 22 Waterloo batters in a Midwest League game. That mark still stands. He struck out 264 in 190 innings (12.5 SO9) as an 18-year-old, posting a 15-7 record and 2.61 ERA with 14 complete games and five shutouts. He was out of pro baseball by age 23. An injury suffered in spring training of 1962 did him him.

We also have:

= Barry Zito, USC baseball pitcher (1998)

= Dennis “Mo” Layton, USC basketball guard (1969-70 to 1970-71)

= Rudy May, California Angels pitcher (1996 to 1974)

= Lee Lacy, Los Angeles Dodgers infielder (1972 to 1978)

= Norm Sherry, Los Angeles Dodgers catcher (1959 to 1962)

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 34: Fernando Valenzuela”