This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 14:

= Mike Scioscia, Los Angeles Dodgers; Anaheim Angels manager

= Gil Hodges, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Sam Darnold, USC football

= Johan Cruyff, Los Angeles Aztecs

= Drew Olson, UCLA football

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 14:

= Robbie Rogers, Los Angeles Galaxy

= Tom Ramsey, UCLA football

= Justin Williams, Los Angeles Kings

= Edson Buddle, Los Angeles Galaxy

= Sam Perkins, Los Angeles Lakers

= Tina Thompson, USC women’s basketball

The most interesting story for No. 14:

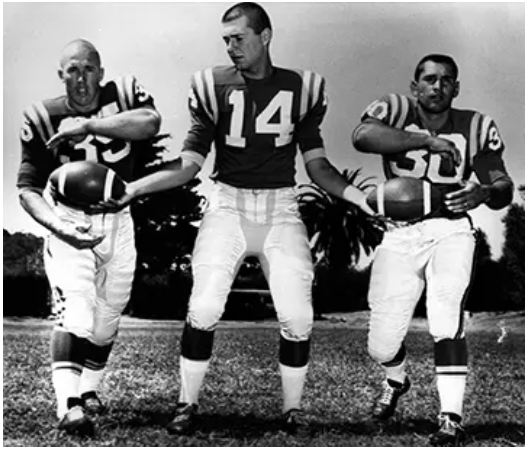

Ted Tollner, Cal Poly San Luis Obispo football quarterback (1958 to 1961)

Southern California map pinpoints:

San Luis Obispo, Los Angeles (Coliseum), Anaheim

Author’s note: San Luis Obispo is commonly considered part of Southern California due to its proximity to Los Angeles. Geographically, it falls within the state’s Central Coast region. For our purposes, it works as a SoCal story.

Survive and advance was one way to summarize Ted Tollner’s career as a college and NFL football coach for more than 30 years of his life.

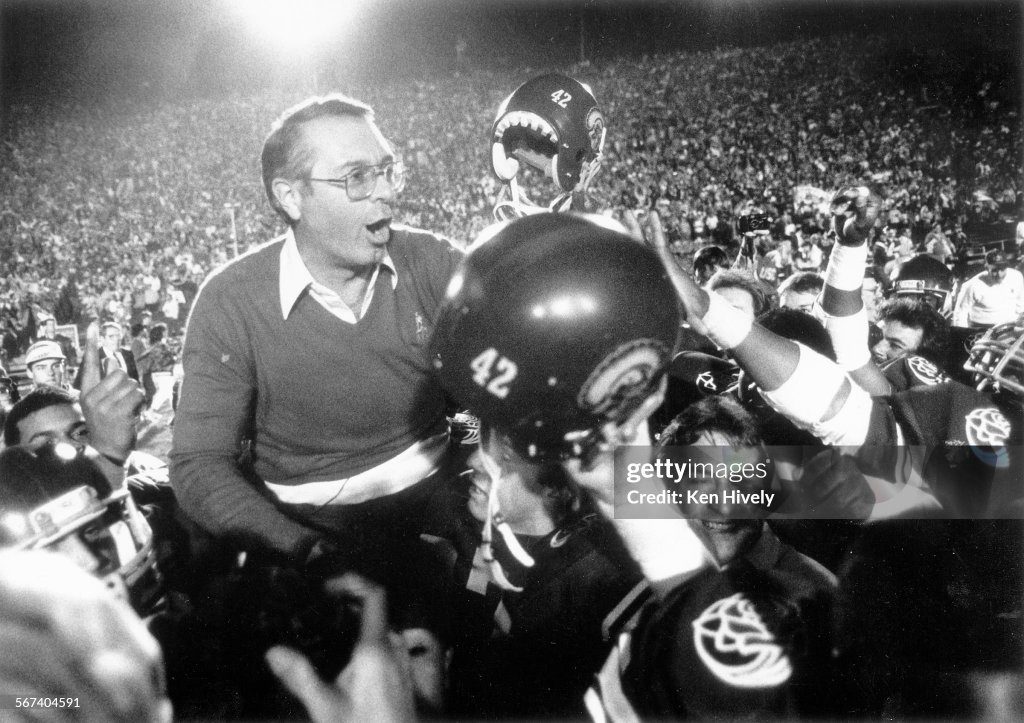

Four of them most notably came when he stepped up and into the legendary lineage of USC’s head man. In his time as the successor to John Robinson between 1984 and ’86, a 26-20-1 record and three bowl appearances, most notable winning the 1985 Rose Bowl in his second season after clinching the Pac-10 title with a 7-1 mark, highlighted his resume before he re-emerged for eight seasons at San Diego State.

Two of his 15 years as an NFL assistant were as the quarterbacks coach for Chuck Knox’s Los Angeles Rams. As the team planted itself in Anaheim, and Jim Everett was Tollner’s main pupil, the teams were hardly spectacular, spurting to 6-10 and 5-11 finishes in 1992 and ’93.

Yet anytime Tollner needed a tolerant reminder that just being on the sidelines and watching a scoreboard clock ticking down was a blessing, even if his left ankle was starting to get a little cranky, he could flash back the time in his life when he was the All-Conference quarterback at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, wearing No. 14.

On a Saturday afternoon, Oct. 29, 1960, Tollner had perhaps his most notable game when he threw for a career-best and school-record 246 yards. It was a bit of an afterthought in that his team list, 50-6 loss, at No. 4 Bowling Green, dropping the Mustangs to 1-5.

That evening, as Tollner and his teammates were wearily boarding a plane to fly back home, something terrible happened.

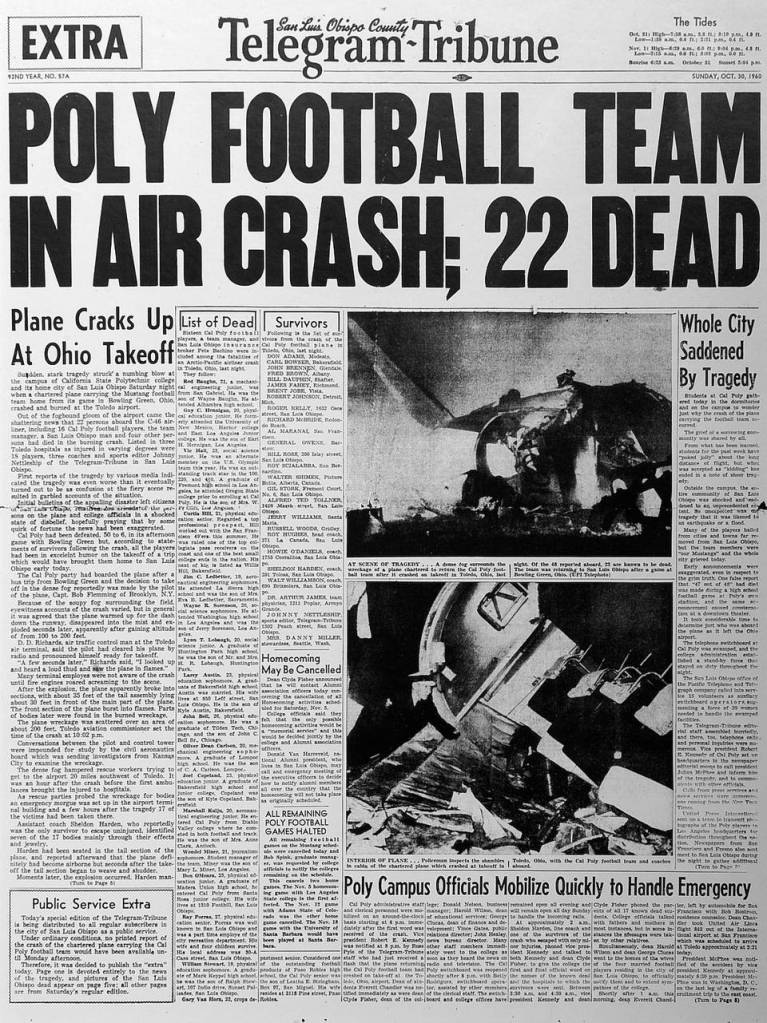

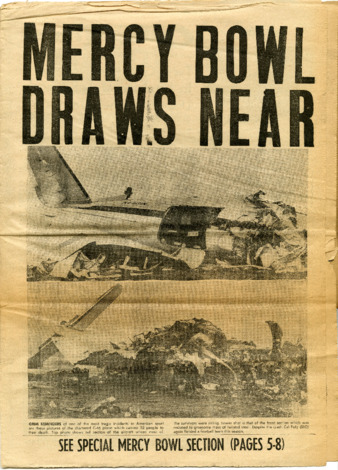

Their aircraft wrecked on takeoff out of Toledo, Ohio, flipping over and bursting into flames.

It was the first airline crash involving a U.S. sports team.

Of the 22 who died, 16 were Tollner’s teammates. They were in the front of the plane. Tollner was one of 26 survivors, because he agreed to switch seats at the last minute and was sitting in the back.

“Anytime I’m feeling sorry for myself, whether it’s from getting fired or losing a game, (the tragedy) has been my strength,” Tollner would say again and again. “You’re here for whatever reason and getting an opportunity to do something good. I’ve drawn strength from it — for whatever reason you’re spared, so make it a positive thing.”

The background

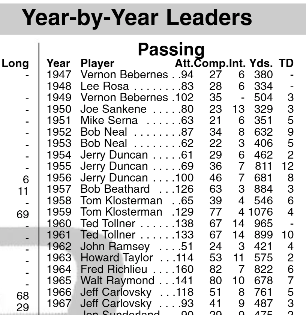

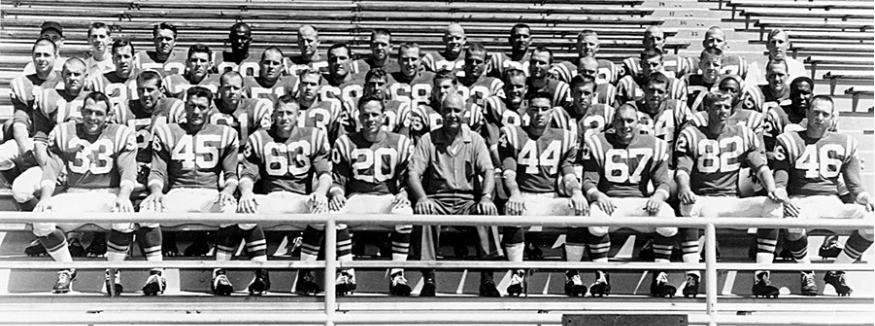

From 1952 to 1959, Cal Poly’s football team combined to post a 59-18 record, including 9-0 in ’53. Tom Klosterman, the older brother of Loyola quarterback great Don Klosterman, and future San Diego Chargers GM Bobby Beathard, out of El Segundo High and El Camino College, were the dual quarterbacks for the Mustangs before Ted Tollner arrive.

Prior to 1960, most of the team’s successes were due to an experienced senior class. Tollner was part of a new wave of underclass talent coming in from a 6-3 team in ’59.

In the 45 years of Cal Poly’s football program, one other element was of interest: It had never traveled very far East to play an opponent before deciding it was worth going to Ohio to face Bowling Green, coming off the 1959 small college national championship and led by talented receivers Bernie Casey — a future NFL player with the Los Angeles Rams and later a Hollywood actor.

Poly’s 44-point loss that late October day in 1960 didn’t sit well — its only score was a 60-yard punt return. But the upside is it might provide experience for the team’s return tor conference play, which would resume with a homecoming game against Cal State L.A. in early November.

A twin-engine Curtiss C-46 passenger plane owned by a company called Arctic-Pacific was set to leave at 8 p.m., but was already two hours behind schedule for what would be an 11 ½-hour flight with stops in Kansas City and Albuquerque before going to Santa Maria. The plane just flew the Youngstown football team back from Connecticut after its game and was refueling.

Tollner took a seat in the front part of the plane. Curtis Hill, Tollner’s favorite receiver who was a three-year starter and led the team in 1960 with 447 yards receiving and three touchdowns, remembered how ill he had been on the flight East to Toledo and didn’t want it to happen again — he asked Tollner if he could switch seats because, it he sat closer to the front, he would cut down on feeling the plane wobbling. Tollner obliged.

Bowling Green’s Casey recalled later meeting up with Hill after the game at the campus’ student union building, as some Cal Poly players went to Halloween parties at campus sororities.

“We were talking about California (because) it had such a mystique for me, being raised in Ohio,” Casey said. “We were talking about the East-West Shrine game. I told him that maybe I’d see him out there.”

Cal Poly head coach Roy Hughes got confirmation from the pilot it was OK to take off despite reservations about the visibility. Someone on the plane was heard to yell, “Let’s give it the old college try.”

At 10:01 p.m. the plane headed down the runway. During the initial climb, it lost control as the dense fog from Lake Erie that rolled in earlier made it harder to see. The plane rose to about 100 feet above the runway, was airborne for about 30 seconds, then it started shaking and vibrating uncontrollably.

“I was sitting right on the left wing and you could just tell,” Tollner said. “The engine sputtered and then it just stopped. … I knew we were going to go down. You just kind of tucked up into a ball and covered your head. The next thing you know, there was a crash.”

The plane, once used by the military as a transporter in World War II, had stalled and eventually landed in an orchard about a mile from the runway. It split in two parts. All of those in the front part of the plane — including Hill, who traded seats with Tollner — perished. Tollner was alive and strapped in his seat, but his left foot, under the seat in front of him, was turned backward, caught in a foot rest.

The plane burst into flames a few moments later.

“It was chaos,” Tollner said.

Once he regained consciousness, Tollner was told that he went into shock. His first instinct was to get up and help his teammates but “I couldn’t figure out why I couldn’t walk,” he said. “A teammate, Carl Bowser, unstrapped me, and he and Dick McBride dragged me away from the burning plane. That’s how I got away.”

“I dragged Ted out of the sucker, ” Bowser said. “He was laying there.”

Of the 26 who survived with Tollner, 18 were his teammates. There was also the team physician, all four coaches and a flight attendant. One of the surviving coaches, Walt Williamson, went on to become the athletic director at Cal State Los Angeles.

Ray Porras, a 27-year-old running back who grew up in East L.A. and had a wife with four children, was one of the 22 who died. Also perishing were Wayne Sorenson and Guy Hennigan, transfers from L.A. Harbor College. That’s also the school where student manager Wendell Miner came to Cal Poly from and would not make it out alive.

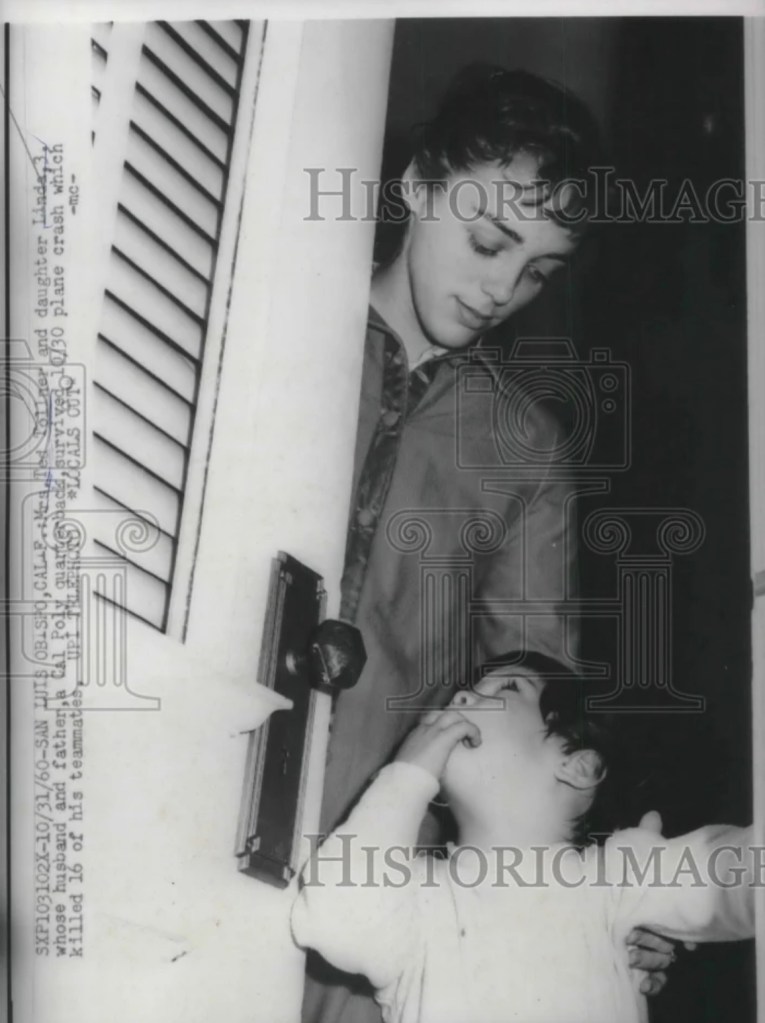

The fog hindered ambulances trying to reach the crash site and airport 20 miles east of Toledo. News reports were sketchy. All were feared dead. That is what the first bulletin said the news came, breaking into the “Ed Sullivan Show,” which Tollner’s wife, Barbara, was watching on television at home in San Luis Obispo. She was with their young daughter, Linda.

Hours later, word came of survivors, and a nurse from Toledo’s Mercy Hospital phoned Tollner’s wife to confirm that he was among them.

After the crash, a United Press International photographer caught up to Barbara and Linda Tollner at their home and distributed an image to news service clients.

At 3:30 a.m. Pacific Time, Cal Poly school journalism teacher Robert Kennedy and dean of students Everett Chandler and Clyde Fisher began telephoning the parents and wives to inform them of those were were gone.

“It was one of the most nightmarish, heartrending tasks I’ve ever attempted,” Kennedy later recalled. “The worst part of it was calling the parents, most of whom didn’t know there was a wreck.”

The aftermath

John Madden, the future Hall of Fame NFL coach and broadcaster, had played at Cal Poly in 1957 and ’58 with Beathard. Madden went to the campus that Sunday morning to console friends and family returning from the crash.

Over time, stories spread that Madden was on the plane, or he missed the flight, and that all triggered his aversion to flying.

“Neither one is true,” Madden would say. “I didn’t like getting on planes before that. I got claustrophobic, and it got worse over the years.”

The homecoming rally turned into a wake in the main campus gym on Halloween. The final three games of the 1960 season were canceled.

Cal Poly did not play another game outside of California for nine years following the crash. It did not play another game east of the Rocky Mountains until 1978, an NCAA Division II playoff loss in North Carolina.

Shaken by the crash, Bowling Green decided to avoid air travel and instead took a train to its next road game — a 2 ½-day ride to play Texas Western in El Paso.

“Oct. 29, 1960, took a toll on a lot of us,” Tollner told the Toledo Blade in 2002, prior to a Cal Poly game at the University of Toledo. “It’s a day none of us will ever forget.”

There was never talk of cancelling the Cal Poly football program in 1961. Tollner wanted to keep playing despite his badly dislocated ankle that somehow was healthy enough to play on. Doctors initially doubted it could be saved because of a lack of blood supply and avoided fusing it so he could keep mobility.

Head coach Roy Hughes, who compiled a 73-37-1 record in 12 seasons before leaving after the 1961 campaign, was in a Toledo hospital for nine days with scalp wounds and major damage to his thigh and knee after the crash. He tried to rally the surviving players together — led by Tollner, one of 10 survivors who came back to play in 1961.

“The program went downhill after the crash,” Hughes said years later. “Kids didn’t want to come here. Who could blame them? We were the school that had the crash.

“One of the most heartbreaking, yet also the most heartwarming, sides of the story was the ’61 team. It was so hard for some of them to come back. I used to brag about my ’53 Cal Poly team because it was 9-0, but those ’61 guys went 5-3 on courage you wouldn’t believe.

“Ted Tollner, my quarterback, was all wired together. Roy Scialabba was all crippled up and had no business in a football uniform, but you couldn’t keep ’em away. I was so proud of those survivors who came back.”

Clark Tuthill, a defensive back from Mira Costa High in Manhattan Beach, had played at Los Angeles Harbor College and transferred to Cal Poly but was a redshirt in 1960 and not on the team flight.

“Guys like Ted Tollner … were badly banged up in that wreck and they were back playing football the next year,” said Tuthill. “That was pretty incredible, really incredible, and the fact that Ted even played was miraculous. That guy, you talk about a guy coming back from being really badly injured, that was amazing.”

The ’61 Mustangs finished 4-4, including 3-2 in the California Collegiate Athletic Association for Hughes’ final year. Among their wins were at San Fernando Valley State (43-8 at Monroe High I North Hills) vs. Long Beach State (21-14 at home) and at Cal State L.A. (40-13). Wayne Maples, a fullback on that ’61 team, had been in the program starting as a freshman in 1959 but took the fall 1960 semester off to work and missed the tragic flight. He would graduate with an aeronautics engineer degree in 1963, get a masters degree in math at USC, relocate in Hawthorne with his wife, Darleen, who he met at the school, and start a family.

Tollner, who passed for 965 yards and six touchdowns in six games in 1960, completed his Mustang career in 1961 with 2,244 passing yards and 20 TDs. He completed 49 percent of his throws — 158 of 323.

Tollner had to learn to live with that survivors’ guilt — as did so many others.

“A lot of us had rough edges after the crash,” Bowser later explained. “We were raising too much hell, living a life of looseness, partying as if we figured what the heck, we might die the next day.”

On Thanksgiving Day, 1961, Tollner was suited up in his Cal Poly uniform and in the Los Angeles Coliseum, but not to play a game.

A Thanksgiving Day game called the Mercy Bowl was established to honor the team and raise money for those in need from the crash. More than 33,000 attended to watch CCAA champion Fresno State face Bowling Green. The No. 3 ranked Bulldogs won easily, 36-6.

Before the contest, Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray wrote about why the Mercy Bowl was important: “It is the obligation of all of us interested in athletics. I can think of no better way to give thanks on that day that we are here and healthy, than to contribute to those who are alone with only memories on that day.”

Every June, those survivors who able to make it meet up at the home of former teammate Rich Max, the center on the ’59 team.

During a story in the San Luis Obispo Tribune on the 40th anniversary of the crash in 2000, team member Bill Dauphin, a sophomore reserve tackle making his first plane trip, recalled that he sat near the center of the aircraft. Eight teammates on either side of him were killed. Dauphin was found some 30 feet north of the tail section, torn out of his seat and suffering from a dislocated hip, a shoulder injury and burns. He was unconscious nine to 11 days, he was told. He said what returned a sense of normalcy to his life was playing football the next year.

“That was such a huge healing thing for me, just to have the team and be out there on the field,” he said. “I think of someone like Ted Tollner, limping back to the huddle because of (crash injuries). That was awful to see, but he was a hero to me and a lot of those guys.”

Tollner, who got his bachelors degree in physical education in 1962 and a masters degree in education in ’65 at Cal Poly, was drawn to coaching after his classwork was finished.

First he coached in high school, then junior college, in his native San Francisco Bay area. He was brought in as the San Diego State offensive coordinator from 1973 to 1980, and became the highly regarded quarterbacks coach at Brigham Young in 1981 under LaVell Edwards, where the team finished 11-2 and was ranked No.13 with freshman quarterback Robbie Bosco.

A year after becoming John Robinson’s offensive coordinator in 1982, Tollner was promoted to head coach when Robinson stepped down to take a USC administrator role. The fact Robinson and Madden were close childhood friends, and Madden was well award of Tollner’s Poly playing days couldn’t have hurt Tollner’s attraction to Robinson while at USC.

While Tollner’s first season with the No. 9 ranked Trojans would end 4-6-1 (4-3 in the Pac-10), starting with a 19-19 tie against No. 18 Florida, the next season was highlighted by an upset over No. 1 Washington on Nov. 10, 1984. Despite losing to UCLA and Notre Dame in back-to-back-weeks, the Trojans finished with a No. 10 ranking in the AP poll after a 20-17 victory against then-No. 6 Ohio State in the 1985 Rose Bowl. The win was orchestrated by quarterback Tim Green, who Tollner nurtured along following the injury to starter Sean Salisbury.

Four seasons of a combined 1-7 record against rivals UCLA and Notre Dame were the penalty flags of his tenure through 1986. Tollner would later log in eight seasons as the San Diego State head coach, posting a 43-48 mark from 1994 to 2001.

“In coaching, you can get awfully hung up on a season not going right, the stress and the criticism, especially if you’re a head coach, ” Tollner said in 2003. “It can become extremely stressful. If you let it get to you, you start feeling sorry for yourself, and you can’t do that. “(The plane crash) helped get me through those times, whether it was at SC or different jobs where more of the vocal criticism goes to you.”

The Coliseum plaque dedicated to the Mercy Bowl in 1961 was something Tollner could visit while he was coaching at USC. He said the memory was never too far away.

“There are so many bowls now, I have trouble keeping track of all of them, and I’m in the business,” Tollner said in 2008. “I’ve been lucky and gotten to coach at a lot of bowl games. Head coach at a Rose Bowl win. But I don’t think any of them were any more meaningful than the Mercy Bowl.”

When Tollner was inducted into the Cal Poly San Luis Obispo Athletics Hall of Fame in 1989, it noted his four seasons as a pitcher on the Mustangs’ baseball team, representing the USA team in the 1962 Pan American games.

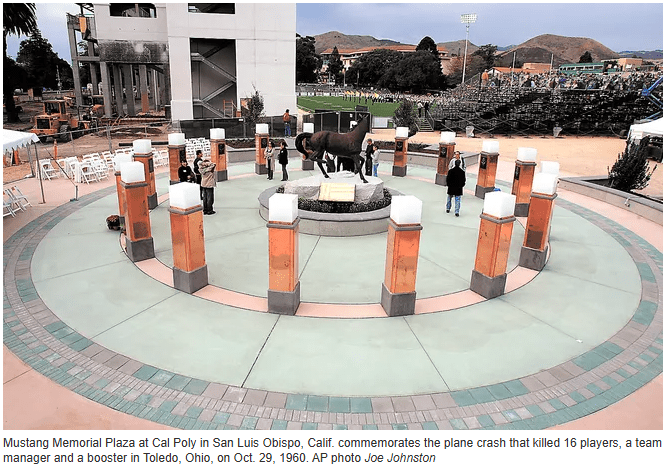

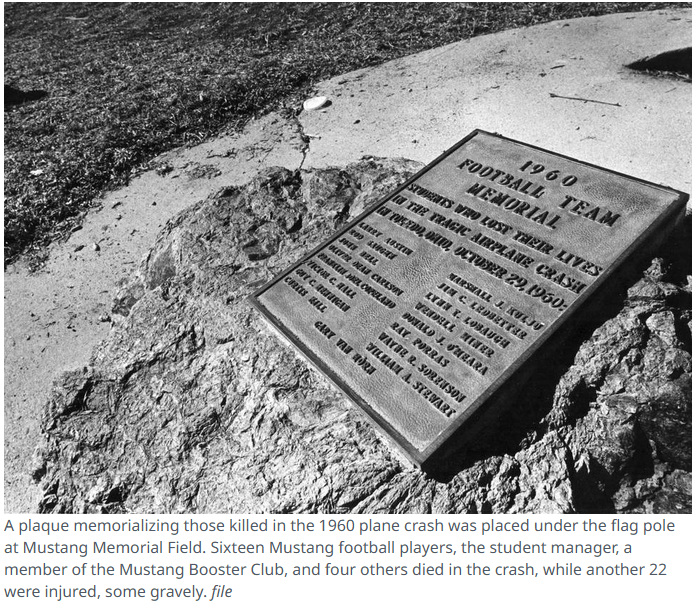

The entire 1960 football team was inducted in the school’s Hall in 2006, on the event’s 46th anniversary. The next day, at a Cal Poly home game against Southern Utah, the football field was dedicated as Mustang Memorial Field, with former players and members of the crash victims’ families at midfield.

Tollner was there. Even as his ankle was acting up.

“I said, ‘What’s arthritis?’ You really don’t know, “ Tollner told the San Luis Obispo Tribune in 2003. “So I get a little bit. It swells up on me a lot when I’m on it. But it’s all relative. When I see some of the friends I have that are still alive, their burden of what they’ve had to carry injury-wise is far more serious.”

In 2008, when asked again about the crash, Tollner reflected in a story by the Associated Press:

“A lot of things go through your mind when you get an extra bonus of 48 years to live. Why me? Why not them? You don’t know why. You think about those things when you’ve been spared.”

Tollner’s fears of flying have faded but still return on occasion.

In 2010, when he was an assistant with the Oakland Raiders coming back after a charter flight from a win at Denver, air turbulence bothered him.

“Any kind of similar weather to that day,” the then 70-year-old Tollner told the Los Angeles Times on the crash’s 50th anniversary. “Any kind of inclement weather, and something in my body reacts to that. I get real uptight about it.”

Holidays, such as Thanksgiving, also cause him to reflect. Especially with the Mercy Bowl anniversary every year.

“Anybody that’s been in any kind of accident or something where people didn’t survive, you reflect on the really important things in your life, ” said Tollner, who in June 2024 received an honorary doctor of humane letters during the Cal Poly College of Science and Mathematics ceremony. “That’s the biggest thing that’s come out of it for me. Don’t dwell on anything negative that has happened. Do something productive because of the good fortune that you are still here.”

Who else wore No. 14 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

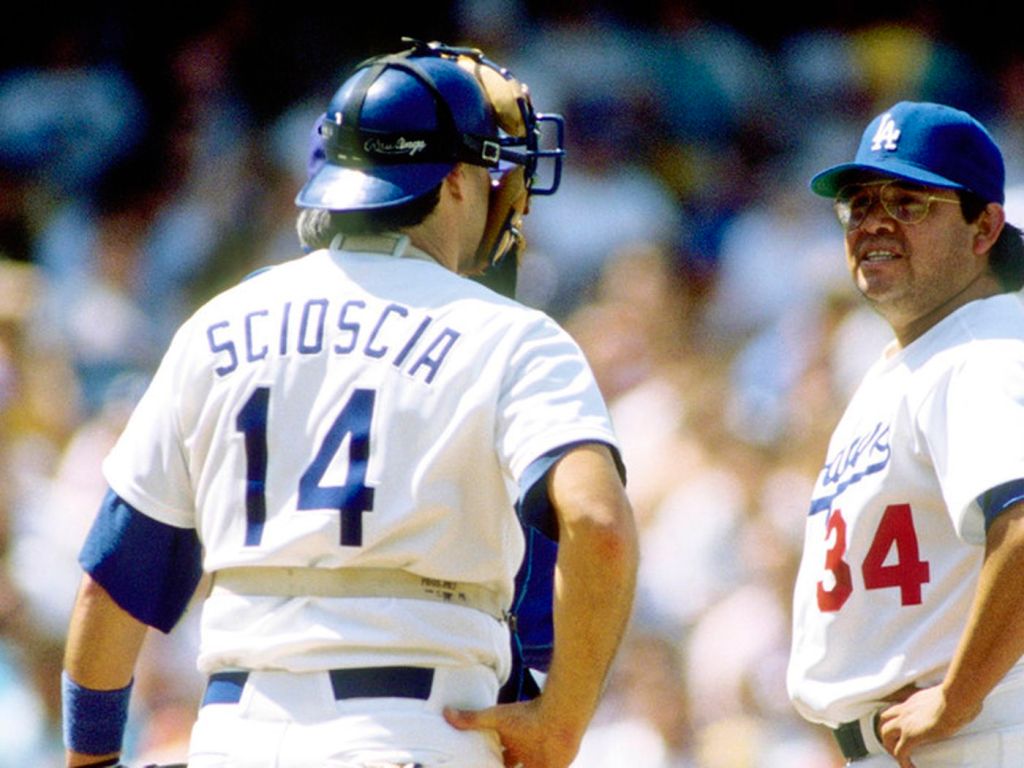

Mike Scioscia, Los Angeles Dodgers catcher (1980 to 1992), Dodgers coach (1997 to 1998), Anaheim Angels/Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim/Los Angeles Angels manager (2000 to 2018):

Best known: The Dodgers’ all-time leader in games caught (1,395), Scioscia locked down the starting role in ’82 as a fearless defender of the plate after sharing the role with Steve Yeager. Scioscia’s 1988 playoff heroics also played into his Dodger lore, including a ninth-inning, game-tying home run off the New York Mets’ Dwight Gooden in Game 4 of the NLCS, a game the Dodgers won in extra innings to stay alive. After several seasons as a coach, Scioscia was hired away to be the Angels’ manager, and he took them to their only World Series title as a wild card team in 2002. Scioscia became the first manager to reach the playoffs in six of his first ten seasons and drew two AL Manager of the Year Awards (’02 and ’09) to go with 1,650 regular-season wins and a 21-27 post-season record. And only 47 ejections.

Not well known: Scioscia came up as a rookie with Fernando Valenzuela and the two combined 239 times as a batter mate — second in the franchise history after the 283 times Don Drysdale teamed with John Roseboro.

Gil Hodges, Los Angeles Dodgers first baseman (1958 to 1961):

Best known: The reason the Dodgers finally retired No. 14 came after his 2022 election into the Baseball Hall of Fame, which was more than 60 years after he last played for the team. Hodges’ first 14 years were in Brooklyn — starting as catcher wearing No. 4 in 1943, followed by two years in the Marines in World War II, then back for Jackie Robinson’s arrival in ’47. Hodges’ switch to No. 14 came when rookie Duke Snider was given No. 4 in 1947, and Hodges moved from catcher to first base, the position where Robinson had debuted. Robinson was now at second, and Roy Campanella arrived in ’48 to do the catching. For his four years playing in Los Angeles, Hodges was a key part of the ’59 World Series team, hitting .340 in June with seven homers and 23 RBI in 30 games. On the Dodgers’ franchise list, Hodges’ 2,006 games played (fourth best), 361 homers (second best) and 1,274 RBIs (second best) remain near the top. At the time he retired, no other right-handed NL batter had more home runs than him in the game’s history with his 370.

Not well remembered: When MLB gave out its first Gold Glove Awards in 1957, a combination of both NL and AL players, Hodges was the first baseman, and he received the honor as the NL player in ’58 and ’59 when the teams were chosen by leagues.

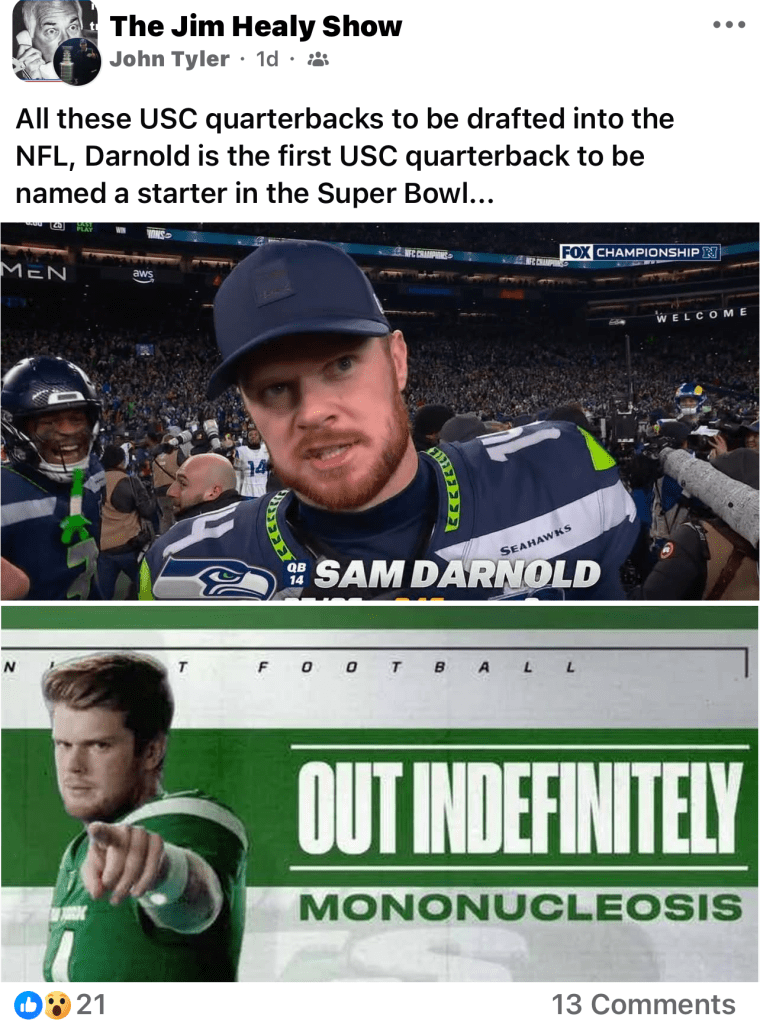

Sam Darnold, USC football quarterback (2015 to 2017):

Best remembered: The 6-foot-3 standout from San Clemente High put up a 20-4 record as a starter, giving the job in Week 4 of his freshman year and leading the team to a 9-1 finish. He set a freshman record with 26 touchdown passes and 230 yards rushing. His combined redshirt freshman and sophomore seasons turned out to produce 7,229 yards passing and 57 touchdowns against 22 interceptions for a 153.7 QB rating. Darnold threw for 453 yards (33 of 53) and five touchdowns in USC’s 52-49 win over Penn State in the 2017 Rose Bowl. As a redshirt sophomore and early Heisman favorite, Darnold had a tough start but brought the Trojans through the Pac-12 Conference championship game with a 31-28 win over Stanford (as the game MVP), and that sent them to the Cotton Bowl.

Not well remembered: When Darnold arrived at USC so unheralded, recruited as a linebacker and sitting out the 2015 season as a third-string QB, he said he was just handed jersey No. 14 because he wasn’t well-known enough name to demand a number like some USC freshmen do every year. “I just took the number they gave me,” Darnold said. “I never really thought it. It’s not something I really think about. I didn’t care what number I wore.” Darnold went to the New York Jets as the NFL’s No. 3 pick overall in 2017 and, by 2026, he had this distinction:

Tina Thompson, USC women’s basketball forward (1994 to 1997):

Best known: The Morningside High teammate of Lisa Leslie followed her to USC, eventually to the WNBA Sparks, and into the Basketball Hall of Fame. In high school, she scored over 1,500 points and had 1,000 rebounds. In four years at USC she averaged nearly 20 points and 10 rebounds a game and was all-conference first team three seasons in a row. She became the first pick overall in the WNBA draft of 1997, led Houston to four titles, won two Olympic gold medals and became the league’s all time leading scorer through 2014, also playing three seasons for the Los Angeles Sparks (wearing No. 32) from 2009 to 2011. In 2019, USC retired her No. 14 jersey.

Drew Olson, UCLA football quarterback (2002 to 2005):

Best known: Eighth in the Heisman voting as a senior, Olsen had 34 of his 67 career TD passes in his final year when he also threw for 3,198 yards with just six interceptions. UCLA’s 10-2 finish led to a Sun Bowl apperance and a win after the Bruins came back with a 22-point rally. When he was finished at UCLA, he was second all-time for passing yards (8,532), completions (664) and touchdowns (67).

Not well remembered: Olson broke Cade McNown’s school record with a six TD game against Oregon State.

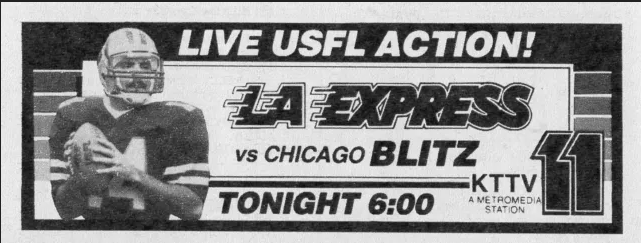

Tom Ramsey, UCLA football quarterback (1979 to 1982); USFL Los Angeles Express quarterback (1983 to 1984): The standout from Kennedy High as the headline rival of Granda Hills’ John Elway, Ramsey was co-MVP of the 1983 Rose Bowl (a 24-14 win over Michigan). His career mark of 31-13-2 as well as breaking season and career marks at the school to that point earned him induction into the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 1998. He ventured into the USFL as a pro for two years prior to the team locking in Steve Young as its quarterback.

Justin Williams, Los Angeles Kings right wing (2008-09 to 2014-15): “His dressing-room nickname with teammates was ‘Stick.’ The rest of the world called him ‘Mr. Game 7’,” it said in the lede of a story by the Athletic on Williams in 2022 when he was in the Carolina Hurricanes’ administration. The Kings’ Stanley Cup wins in 2012 and ’14 are testament to why the team acquired him in March of 2009 from Carolina for Patrick O’Sullivan. Williams was named the Conn Smythe Trophy winner after the 2014 playoffs. In the Final series against the New York Rangers, Williams led all players with seven points in the finals, including a dramatic overtime goal in Game 1. He had three assists in the Kings’ double-overtime win in Game 2, and he added another assist in Game 3. For the ’14 postseason, he had nine goals and 16 assists, including the Kings’ first goal early in the Game 6 Final clincher. And before the Cup finals, Williams also reminded the hockey world why he’s called “Mr. Game 7.” He had two goals and three assists in the Kings’ three Game 7 victories during their resilient playoff run, including timely goals against Anaheim and Chicago. Williams also had a pair of two-goal games when the Kings faced elimination in the first round against San Jose, becoming the fourth team in NHL history to rally from a 3-0 series deficit. By the way: Williams is 7-0 with seven goals and an NHL-record 14 points in Game 7s in his career.

Brandon Ingram, Los Angeles Lakers small forward (2016-17 to 2018-19): A No. 2 overall pick and starting 40 games as a 19-year-old his rookie season, Ingram had a team-high 18.3 points per game in 2018-19 before being traded to New Orleans in the deal for Anthony Davis.

Sam Perkins, Los Angeles Lakers forward (1990-91 to 1992-93): Signed as a free agent, Perkins averaged 14.6 points and 5.4 rebounds in his three seasons before the team absently mindedly traded him to Seattle for Benoit Benjamin and Doug Cristie in the middle of the ’92-’93 season.

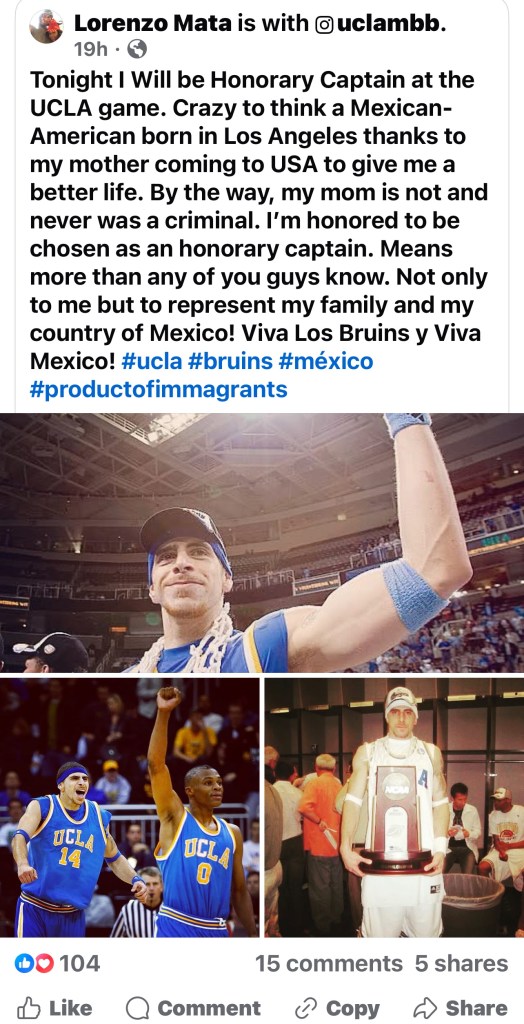

Lorenzo Mata-Real, UCLA basketball center (2004-05 to 2007-08): From South Gate High, Mata came in a Bruins recruiting class with Jordan Farmar, Josh Shipp and Aaron Afflao to get to back-to-back Final Four appearances in 2006 and ’07. Mata added his mother’s last name (Real) to his jersey during his senior season.

Edson Buddle, Los Angeles Galaxy forward (2007 to 2010, 2012, 2015): The Galaxy already had Carlos Ruiz, Landon Donovan and Alan Gordon as attacking forwards, plus David Beckham, when the 25-year-old Buddle started the 2008 season, but he became a celebrated scorer himself, landing two hat tricks in Week 8 and Week 12. By 2010, Buddle was an important part of the Western Conference title, winning team MVP, the golden boot and Humanitarian of the Year. Circling back to L.A. after a year in Germany, he only started 10 games for the Galaxy and scored three goals, and was traded to Colorado. He came back a third time in ’05 to play 12 games without a goal or assist.

Mike Liebethal, Los Angeles Dodgers catcher (2007): The Westlake High standout got to spend the last 38 games of his 14-year MLB career with his hometown Dodgers. The two-time NL All Star and Gold Glove winner had been drafted out of high school in the first round by the Philadelphia Phillies and became their longtime backstop, hitting 31 homers and driving in 96 during the 1999 season.

Have you heard this story:

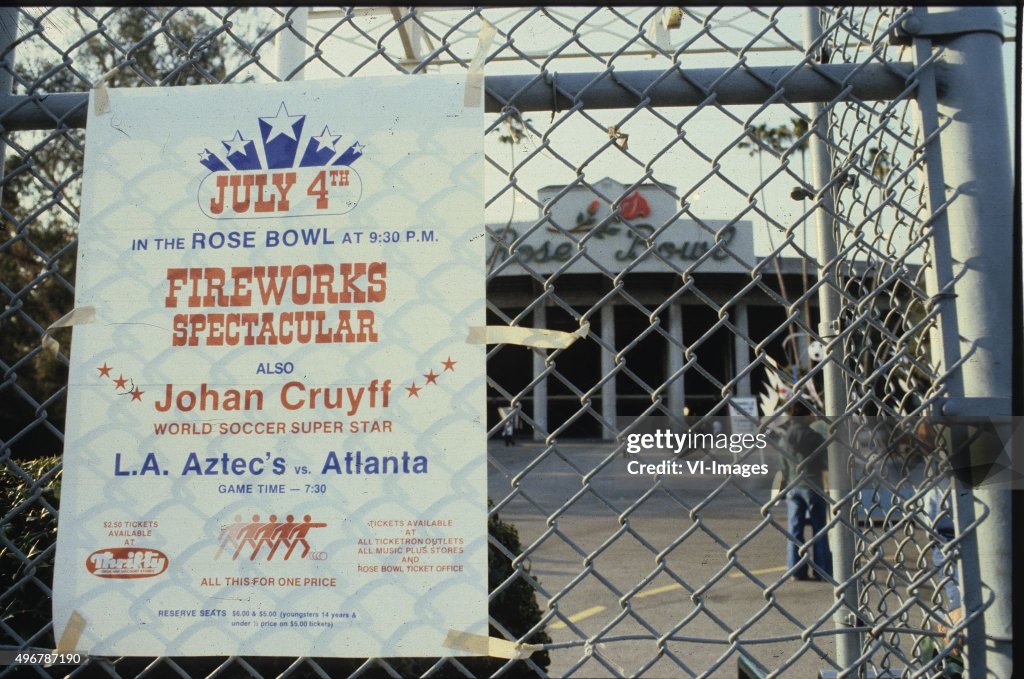

Johan Cruyff, Los Angeles Aztecs forward/attacking midfielder (1979):

The Dutch national treasure and captain took his country to the 1974 World Cup final and seemed to be all but retired from the game at age 31 in 1977, having played as a professional with Ajax (1964 to ’73, winning three European Cup titles) and then Barcelona (1973 to ’78, winning La Liga and the Ballon d’Oro three times). But the story goes that because Cruyff blew through all his money and became bankrupt as a businessman — much of it with a insolvent pig farm — he decided to seek some fortune in America. Specifically, with the North American Soccer League. After a deal with the New York Cosmos didn’t happen, he checked in with Los Angeles and took a $500,000 deal, although Cruyff claimed he could have made much more money by returning to Barcelona, considering it offered him $3 million for the 1978-79 season. That’s the amount he turned down so he could retire. Barca was allegedly still offering more than $2 million. With the Cosmos, he could have been on a team with more star power, but he gravitated to L.A. “The Cosmos drew a lot of fans with Pele,” he said. “Even after he left, they drew a lot of fans. So I thought my job should be on this (West) coast.” And he made it look easy. His one and only year with the Aztecs was at the Rose Bowl, reunited with his coach Rinus Michels. In his first game jetlagged by the long trip and nine-hour time difference, Cruyff scored twice in his first seven minutes and also gave an assist before coming off. He would net 14 goals and 16 assists, lead his 18-12 team to the conference semifinals, was on the All-NASL team with the Cosmos’ Franz Beckenbauer and Giorgio Chinaglia and emerged as the league’s Most Valuable Player. Aztecs owner Alan Rothenberg recalled to the Washington Post: “Johan had the intensity of the best kind of development worker. He was willing to drive hours to talk about soccer for 10 minutes on TV, for nothing.” When Rothenberg then sold the team to a Mexican company that didn’t want to pay Cruyff and instead sought Mexican stars, he went off to play for the NASL team in Washington. Very diplomatic. In the 2025 book, “The Soccer 100: The Story of the Greatest Players in History,” Cruyff came in at No. 4, behind Lionel Messi, Diego Maradona and Pele. Cryuff died at 68 in 2016.

Robbie Rogers, Los Angeles Galaxy fullback (2013 to 2017):

The first openly gay man to compete in a North American pro sports league joined the Galaxy, a team in the area he grew up in as he was born in Rancho Palos Verdes and a two-time high school All American at Mater Dei in Santa Ana. Four years of MLS play with Columbus Crew led to a league title in 2008 on the Home Depot Center field in Carson. As he was playing in England, he said he would retire at age 25 and announced he was gay, announcing on social media: “I’m a soccer player, I’m Christian, and I’m gay. Those are things that people might say wouldn’t go well together. But my family raised me to be an individual and to stand up for what I believe in.” He said he retired to avoid scrutiny in England, but deciding to come back play because retiring made him feel “like a coward,” he came closer to home and was part of the Galaxy’s 2014 MLS Cup title team. He scored his first goal in 2015 on the Galaxy’s LGBT Pride Night. He retired in 2017 because of injuries.

Delino DeShields, Los Angeles Dodgers second baseman (1994 to 1996): In the 2009 book by Doug Decatur, “Traded: Inside the Most Lopsided Trades in Baseball History,” there’s much ado about the Nov. 19, 1993 trade when the Dodgers decided 21-year-old pitcher Pedro Martinez may not have the durability to last long as a major leaguer, and they needed an infielder to solidify their regular-day lineup. Thus, Martinez, who just appeared in 65 games and posted a 10-5 mark with a 2.61 ERA, was dealt to Montreal for 25-year-old second baseman DeShields. It didn’t out so well. For the next three seasons, DeShields, who had been a .277 lifetime hitter, hit for a combined .241 average in 370 games, with 114 stolen bases. In two post-season appearances in ’95 and ’96, he was 3 for 16 in five games and a .188 average. The Dodgers gave him $8.7 million for seasons produced a WAR of 1.7, 3.0 and minus-1.4. As he became known as “Disinterested DeShields,” he signed with St. Louis as a free agent for $1.6 million after the ’96 season and retired in 2001. Martinez, by contrast, lasted 18 seasons, won 219 games, led the league in ERA five times and in strike outs three times and went into the Hall of Fame. Deshields spawned Delino DeShields (not junior), drafted by Houston, spent two seasons at single-A Lancaster, and came up with Texas for a seven-year MLB career.

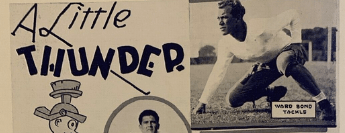

Ward Bond, USC football tackle, 1926-31: At 6-foot-2 and 195 pounds, Bond was a starting lineman on USC’s first national title team of 1928 and graduated in 1931 with a bachelor of science degree in engineering. But his friendship with Trojan teammate Marion Morrison — aka, John Wayne — led the two of them into the movie business. Bond, Wayne and the entire USC team were hired to appear the 1929 movie “Salute”, a football film directed by John Food, and during filming, Bond and Wayne befriended Ford, who would eventually direct them in several major films. Bond appeared in 31 films released in 1935, and 23 in 1939. Rarely playing the lead in theatrical films, he starred in the television series “Wagon Train” from 1957 until his death in 1960.

We also have:

Logan O’Hoppe, Los Angeles Angels catcher (2022 to present)

Kiki Hernandez, Los Angeles Dodgers infielder (2015 to 2020). Also wore No. 8 in 2023 to ’25.

Len Gabrielson, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (1967 to 1970)

Shaun Livingston, Los Angeles Clippers forward (2004-05 to 2006-07)

Slava Medvedenko, Los Angeles Lakers forward (2000-01 to 2005-06)

Darrall Imhoff, Los Angeles Lakers center (1964-65 to 1967-68)

LeRoy Ellis, Los Angeles Lakers center (1971-72 to 1972-73). Also wore No. 25 for the Lakers from 1962-63 to 1965-66.

Brad Holland, UCLA basketball guard (1975-76 to 1978-79), Los Angeles Lakers (1979-80 to 1980-81).

Michael Holton, UCLA basketball guard (1979-80 to 1982-83)

Dan Haren, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2014)

Giorgio Chiellini, LAFC defenseman (2022 to 2023)

Frank St. Marseille, Los Angeles Kings right wing/center (1972-73 to 19976-77). Also wore No. 11 in ’77.

Artimus Parker, USC football safety (1971 to 1973) USC’s career interception leader with 20.

Anyone else worth nominating?

2 thoughts on “No. 14: Ted Tollner”