This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 20:

= Luc Robitaille, Los Angeles Kings

= Don Sutton, Los Angeles Dodgers and California Angels

= Mike Garrett, USC football

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 20:

= Leon Wood, Cal State Fullerton basketball

= Carlos Ruiz, Los Angeles Galaxy

The most interesting story for No. 20:

Darryl Henley, Los Angeles Rams defensive back (1989 to 1994), via Damien High in La Verne and UCLA

Southern California map pinpoints:

Baldwin Villages, Duarte, Ontario, Upland, La Verne, Westwood, Anaheim, Brea, Santa Ana

Try this approach at “Twenty Questions” as a way to explore how Darryl Henley, an Inland Empire prep standout who went from a first-team All-American defensive back at UCLA to spend six years as a Los Angeles Rams’ defensive back, ended up with consecutive prison sentences of about 20 years each by the end of the 1990s.

It’s a story that reality TV show producers and true-crime podcasters salivate over. But it’s a bit more complicated.

Henley continues to serve a 41-year, three-month sentence that times out in 2031, combining a guilty verdict from a trial he endured for drug trafficking, but then on top of a plea agreement for conspiracy to murder a federal judge and a prosecution witness after bribing a prison guard to smuggle a phone into his jail cell.

See if any of this makes sense:

Question 1: What kind of kid was Darryl Henley?

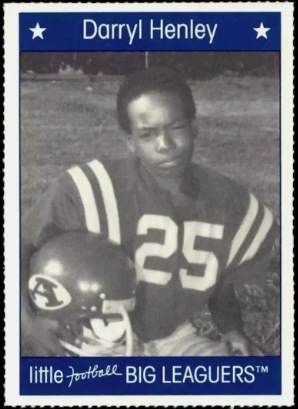

Have a look at the trading card set the Los Angeles Rams included him with after his second season in the NFL. Confidence took a long time overcoming fear, with his mom’s help.

The middle son to Tom and Dorothy Henley was born in L.A. just after the Watts Riots. The family had moved from Hillsboro, Texas to the Baldwin Villages area of L.A. to seek a better life, and then felt safer gravitating to Duarte in the San Gabriel Valley and then Ontario in the Inland Empire.

Darryl almost went to Ontario High, but instead followed his older brother Thomas to Damien High, a private school in La Verne (wearing No. 24), graduating in 1984. Darryl had to watch Thomas set career rushing record at the high school that stood for 20 years and then go on to become a four-year running back/receiver at Stanford (1983 to 1986). He only got into one game playing in the NFL with San Francisco.

Younger brother Eric would follow Darryl at Damien and then play four years as a defensive back, running back and receiver at Rice University (1988 to 1991). Eric sits at No. 2 on Rice’s all-time leaders in career receptions (186), No. 4 for most receptions in a single season (81 in 1989, good for 900 yards) and No. 4 on career receiving yards (2,199). He is sixth in career receiving touchdowns with 19.

Question 2: What kind of a college player was Darryl Henley?

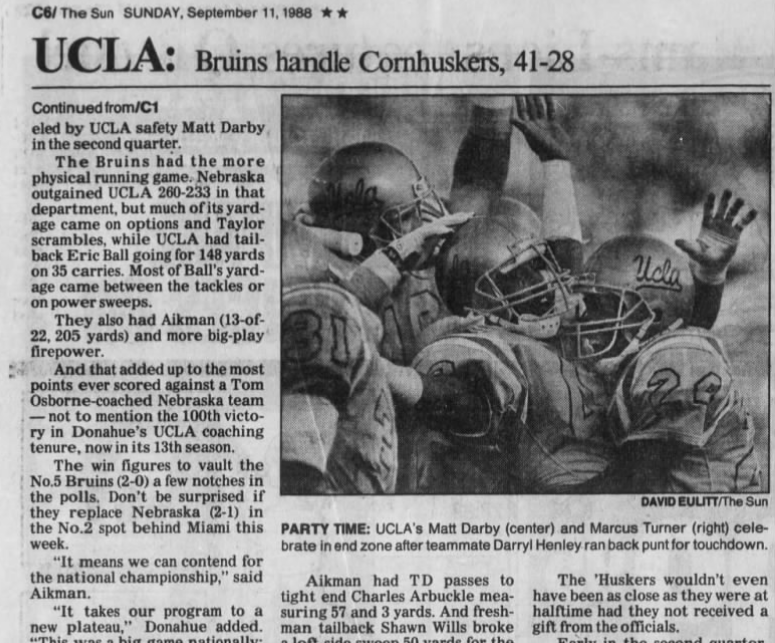

Wearing No. 2 as a first-team All-American defensive back at UCLA (the other first-team corner was Florida State’s Deion Sanders), Darryl Henley graduated with a 3.3 GPA in history. Sports Illustrated’s Rick Telander referred to Henley as “the little return man with braces on his teeth and skates on his feet.” His football career under head coach Terry Donahue: 42 games, six interceptions (including three in one game against Oregon State), a fumble recovery for a 50-yard touchdown, plus averaging 10.2 yards on punt returns (with three touchdowns) and 22.8 yards on kickoff returns. In November, ’86, Darryl’s UCLA team was upset 28-23 by Thomas’ Stanford team at the Rose Bowl. In his senior season, Henley was named UCLA’s Most Improved Player and defensive captain. He was All-Pac-10 as a cornerback and kick returner. His teammates voted him the Sugarman Award for leadership. He was a finalist for the Jim Thorpe Award for the nation’s top DB. The Bruins lost to USC in the final regular-season game for the right to go to the Rose Bowl and ended up beating Arkansas in the Cotton Bowl that season.

Question 3: Was he a highly-sought NFL player?

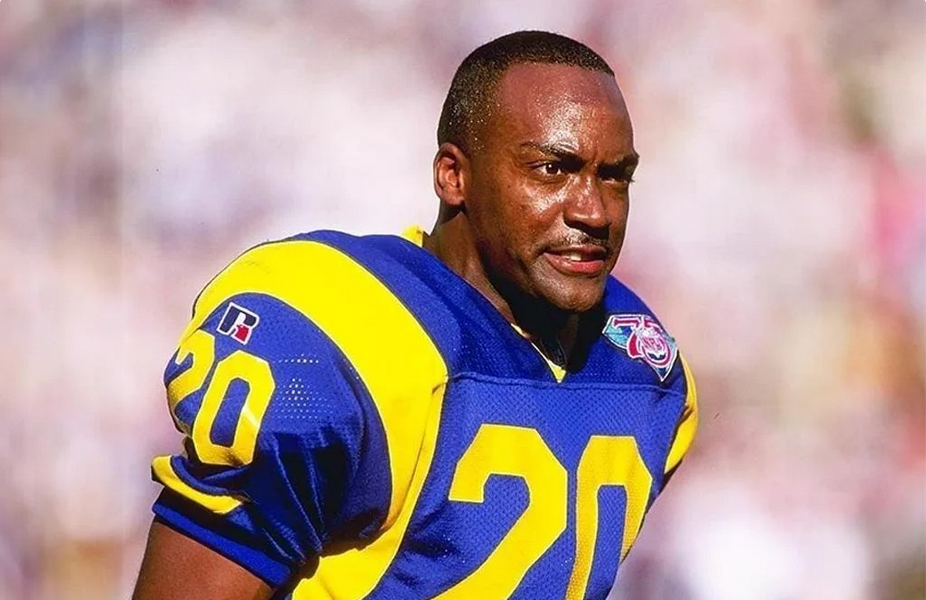

The 5-foot-9, 170-pounder may have lacked size according to pro scouts, but he made up for it with speed and open-field playmaking. Henley was a second-round choice in the 1989 NFL draft by his hometown Los Angeles Rams, coached by John Robinson, took him No. 53 overall. That draft included UCLA teammates Troy Aikman taken No. 1 overall by Dallas, plus defensive back Carnell Lake and running back Eric Ball taken a bit higher in the second round. Henley signed a four year, $1.2 million contract, knowing that down the road, he would prove his value to the team. It allowed Darryl to buy his parents a new house in Upland, and his own home in Brea. The Rams also signed Thomas Henley to the team to join his brother, and the two trained together at Cal State Fullerton.

Question 4: When did he start to make his mark with the Rams?

When the NFL suspended Rams cornerback LeRoy Irvin for violating the league’s substance abuse policy, Darryl Henley replaced him in the starting lineup as a rookie. He was named the team’s Defensive Rookie of the Year, over three other rookies who the Rams drafted ahead of him. Henley would start six games in 1990. The next season, he was a starting right corner back, had three interceptions and was third in the team in tackles. In 1992, focused only on the DB role and not returning kicks, he was third in tackles to go with four interceptions. But the team was 6-10 in Chuck Knox’s first season back as head coach.

Question 5: When did things start to go sideways?

In October of 1993, a federal grand jury indicted four men on trying to extort at least $100,000 from Henley with death threats. One of the men said Henley owed him $350,000 in connection with a drug deal that was foiled in Atlanta regarding more than 25 pounds of cocaine. Two men appeared at Henley’s home in Upland and demanded the loan repayment, leading to Henley, who denied any involvement, cooperating with authorities. As a result, his NFL season was put on hold after the first five games.

Question 6: How did it unravel even more for Henley?

Less than two months later, on Dec. 3, 1993, a federal grand jury indicted Henley on cocaine possession and conspiring to operate an illicit drug network from his home in Brea. Henley surrendered to authorities and was arranged in Santa Ana. His main accomplice was Tracy Donaho, a Rams cheerleader and waitress at a local pancake who was 19 years old and was delivering drugs. Henley said he was merely a silent financial partner in the scheme devised by his childhood friend, Willie McGowan. Henley would miss the last 11 games of the NFL season when the Rams stumbled to a 5-11 finish.

Question 7: Was Henley’s NFL career over?

Not yet. The 28-year-old, on target to make a $1.2 million salary, was allowed to play in 1994 for half his $600,000 pay and under court restrictions that allowed him to travel to road games with a court escort. The Rams were able to help Henley raise $2 million in bail.

“All right!” Henley said of the decision. “Things have been crazy. I hope nothing changes again. I want to play for the Rams. A number of people have gone overboard in helping. Maybe it’s because they believe in the system.”

Henley started 14 of 15 games, had three interceptions (increasing his career total to 12) and made 64 tackles (sixth on the team), giving him 250 in through his 76-game career. And that was that. Same with the 4-12 Rams, who moved out of Anaheim to relocate in St. Louis.

Meanwhile, Donaho, arrested in ’93 for cocaine possession, pleaded guilty and served 14 months in a halfway house.

Question 8: When did Henley get his day in court?

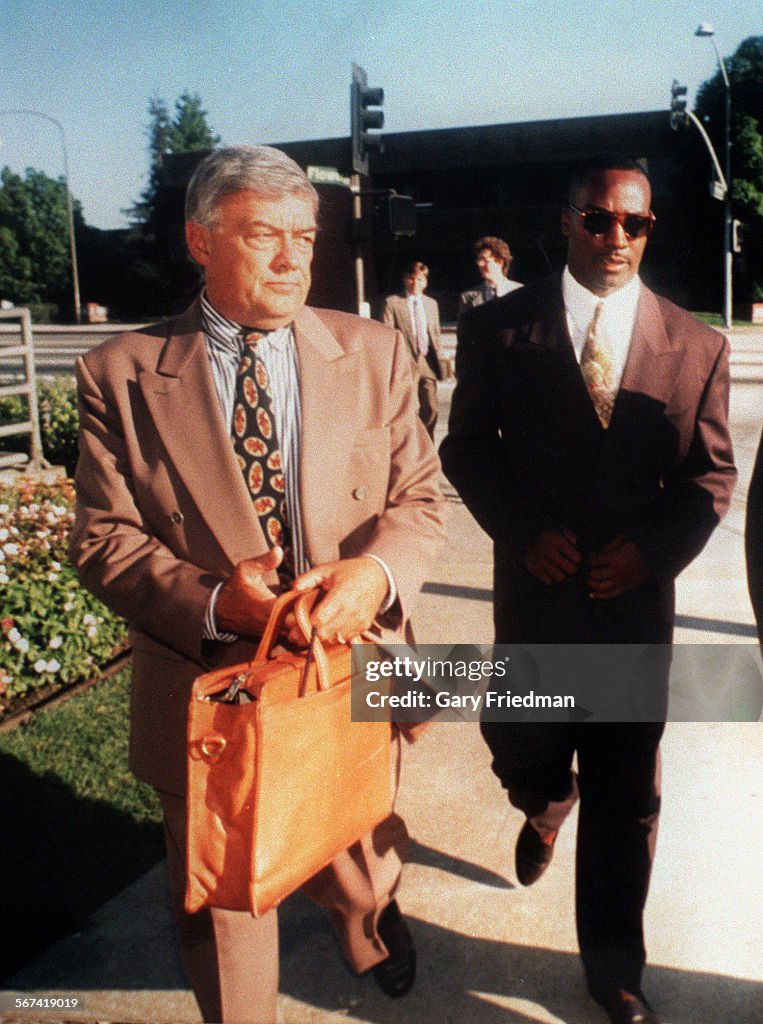

In January of 1995. His attorney Roger Cossack, who was already juggling his time as a legal analyst for CNN’s coverage of the O.J. Simpson trial, painted Henley as a model citizen who was part of an elaborate frame-up. Cossack said Henley was “shocked” when he learned Donaho had been arrested for transporting cocaine.

“Darryl Henley is a young man who but for this has the world by the tail,” Cossack said, adding Henley is only friends with his co-defendants and never participated in a drug conspiracy. Cossack said Henley’s signature was forged on certain receipts, although he didn’t specify by whom.

Question 9: How long did the case last?

Ten months. By October, 1995, Henley and four defendants, including his uncle Rex, were convicted by a jury of drug conspiracy and possession charges.

Question 10: Could it get any worse for Henley?

Sadly, yes. As he was in a downtown L.A. jail awaiting sentencing, authorities said they learned through an undercover police officer than Henley was trying to orchestrate the murder of U.S. District Judge Gary Taylor, who presided in his drug case, as well as arrange for a hit on Donaho. Henley was apparently doing this through a cell phone smuggled to him by a jail guard. As part of a plea bargain, Henley admitted to the later crimes, which included more involvement agreeing to selling heroine to cover the cost of the hits.

Question 11: Who all was involved in that plot?

In June, 1996, Kym Taylor, a former girlfriend of Henley’s, surrendered to authorities to face charges that she helped Henley arrange a drug deal from his jail cell. Taylor was joined by Alisa Denmon, the mother of Henley’s daughter. They were joined by Henley’s younger brother, Eric. Those three, and two others were accused of conspiring to buy about 55 pounds of cocaine from an undercover agent. That complaint came on the heels of heroin charges filed against Henley and a detention center guard who got Henley a cell phone he could use to put a $1-million heroin deal together. Court papers said Henley and guard Rodney Anderson had plans to carry out the hit with the first $200,000 in proceeds from the heroin sales. According to an affidavit, the money was going to pay for the contract killings of Taylor and Donaho. A couple of days later, Henley pleaded not guilty to the new 13-count indictment by a grand jury alleging the murder plots and drug sales.

Question 12: How did Henley’s family deal with all this?

Los Angeles Times columnist TJ Simers interviewed Tom and Dorothy Henley.

“I know he’s telling the truth,” his mother said.

“I haven’t asked,” his father said. “I haven’t had to ask. Darryl’s my son, and I know he’s innocent … Darryl is not exempt from doing wrong. But Darryl is not a dummy. Here’s a young man ready to take off with the Rams – -why would he jeopardize himself and the family he loves so much for some stupid stuff? Once I got that cleared out of my mind it was, OK, we’ll go down together fighting because I know he’s innocent.

“I know that. … When the kids were growing up, everybody was smoking marijuana. I would let my sons use the car and then I would check the ashtrays later. I would go into their rooms and check their drawers. I was searching because as a parent I had that doubt, but I haven’t yet found so much as a roach. Three kids, three sons, and not that my kids are perfect, but not one problem.”

Question 13: Did Henley finally admit to any of it?

In October of 1996, he entered a plea agreement. He was repeatedly asked by U.S. District Judge James M. Ideman if he fully understood the length of time he would be guaranteed of serving in prison if he signed the plea agreement.

“That’s 495 months in prison, do you understand that?” Ideman asked. “That is something like 42 years.”

Henley calmly replied: “Yes, sir.”

Question 14: What happened to Henley’s younger brother, Eric?

In January 1997, Eric Henley entered a guilty plea to charges that he participated in a conspiracy to distribute 25 kilograms of cocaine and heroin. He was sentenced to five years in federal prison.

Question 15: When did Darryl Henley finally find out his punishment?

In March 1997, Henley, now 30, was sentenced in back-to-back hearings by a U.S. District Court. He was sent to one of the toughest prisons in the country — a maximum-security U.S. penitentiary in Marion, Illinois — receiving 260 months (21 years, eight months) for the drug case and 235 months (19 years, seven months) for the murder-for-hire plot.

“You screwed up your life, didn’t you,” said U.S. District Judge Manuel Real.

“Yes,” Henley said in a soft voice.

Question 16: How was Henley handling his jail time at the start of it?

In a 1999 interview with ESPN’s Shelley Smith, Henley said: “Not one thing we did was worth it. Not one place we went. Not one stripper we saw. Nothing, not one thing was worth that. Not one thing was worth them saying — guilty as charged. These are the demons that I have to battle every night.

“You can’t look at me and say, ‘Oh, a product of the environment.’ I have some pretty awesome parents and I was living a dream I worked my ass off for … I lost focus. It was as simple as that. I lost focus as to knowing what got me to where I was.”

The story said a website had been established — DarrylHenley.com — where he wanted to “extend my personal experience to others who may be headed for the same tragedy.” It had an email address and a link to the non-profit Distress Foundation, Inc., which created a defense fund for Henley and accepted contributions for his court appeals. The website has vanished.

Henley said he had a wife who made regular visits, and also stayed connected to a 4-year-old daughter.

“I am going to continue to be the best father I can be to her under these circumstances,” he said. “Some people (say), ‘Well, you don’t have much of a life.’ But I have a life. I have a life where I can still be progressive and still be positive no matter how hard it gets.”

In 2000, as the St. Louis Rams are preparing to play Tennessee in Super Bowl XXXIV — a game Henley might likely be part of without the legal matters — columnist TJ Simers wrote about how Henley had been dealing with his confinement to 21 hours a day in a cell.

“You make a decision, and it’s like you’re drunk,’’ Henley told Simers. “You know you need to call somebody or whatever because you can’t drive. You even entertain the disaster possibilities, but you go against that. You’re too drunk to get in that car, but you get in anyway and something tragic happens.

“That’s what has affected me personally more than anything else. I shouldn’t be locked up, but I put myself in here.’’

Question 17: Did anyone take the time to go over all the trial transcripts, review all the evidence and considered if Henley really had a fair shake?

In 2012, the book “Intercepted: The Rise and Fall of NFL Cornerback Darryl Henley” by Michael McKnight came out. McKnight started the project in 2003 interviewed more than 100 people, including visiting Henley in prison about 10 times, some lasting two or three days. It covered much of the dysfunctional workings of the U.S. legal system, how fame and money could target someone like Henley at that point in time, and especially as society was watching the Simpson trial take place and yearning for justice, somewhere, somehow. McKnight also circled back to Henley’s rookie year with the Rams — then-president George H.W. Bush had a televised speech from the Oval Office vowing to win the “war on drugs” bu adding more prisons, courts and prosecutors to the system. Henley’s case overlapped all that narrative. The book also points out how the other four defendants in the Henley trial were released in the 2003 range, well short of their 10-to-20 year sentencing. There were red flags that came up in the jury pool with drug abuse and racism that wasn’t addressed. Still, an excerpt in a local newspaper had the headline: “How temptation and hubris brought an NFL player to ruin.”

Question 18: What has been the perception of Henley’s crime 20 years into his prison sentence?

In 2015, McKnight wrote a compelling essay for Sports Illustrated, making a case that Henley’s time served should be re-considered a non-violent offender and his release be re-examined.

At the time of the sentencing, President Barak Obama commuted 46 non-violent drug offenders from the 1980s and 1990s who had been part of a crackdown during the so-called “War on Drugs.”

McKnight pointed out that back in ’95, “newspaper readers didn’t concern themselves with the item that appeared about the Henley juror who had called the five defendants “n——” during the trial and predicted that they were “gonna hang.” And even fewer noticed in 2001—after five years of FBI work and court testimony on the issue—when the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals admonished Henley’s trial judge by reminding him that “the Sixth Amendment is violated by ‘the bias or prejudice of even a single juror.’ … Back in 1995, we were too enamored with Cochran, Clark and Court TV to notice the blurb about a second Henley juror who admitted using methamphetamine throughout the trial, or a third Henley juror who had not only discussed the case with the other two misbehaving jurors during their daily carpool, but had showed up unannounced at Henley’s home a week before the verdict to tell Henley that the meth-abusing juror would vote for Henley’s acquittal in exchange for $25,000.”

McKnight also explains that Henley had served his time in Marion, Ill., as well as at a place known as the “Alcatraz of the Rockies” in Florence, Colorado and was now at a low-security federal corrections institute in Mississippi because he used his education to help inmates earn their General Education Diploma (GED).

Question 19: What has Henley himself said publicly about any of this?

In 2018, Henley wrote an opinion piece posted on the FoxNews.com titled “I went from cornerback for the LA Rams to a long prison sentence. Here’s what I’ve learned about reform”

The essay included:

A few weeks ago, I was privileged to receive visit from two members of the clergy. The Rev. Johnnie Moore – spiritual adviser to the White House – and Rabbi Abraham Cooper of the Simon Wiesenthal Center came to see me at the Metropolitan Detention Center in Los Angeles.

For almost two precious hours, these men listened to me share about my hopes and fears, my failures and regrets, and my setbacks and growth. We then spoke of the importance of faith and the messages of truth that so greatly impact men in the solitude of their lives.

Rev. Moore and Rabbi Cooper provided me one of the greatest gifts that day – one of the most effective tools for endurance and hope. They confirmed to me that I have worth and that there is a God who sees me, cares and doesn’t hold me in a prison of eternal condemnation.

If that were not enough, several days later former Washington Redskins cornerback the Rev. Darrell Green spent time on the phone with me, offering me hope through the word of God and reminding me that I am a man of great value whose past does not define me and whose future is in the powerful hand of God.

Words fail to express the impact of these men on my life, and the lives of those around me, as I repeat this message to fellow inmates who are crushed by a sense of hopelessness and despair.

Blaise Pascal – a 17th century French scientist, mathematician and theologian – once wrote: “All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.”

One can say that most of an incarcerated man’s problems stem from his inability to sit quietly in his cell alone and believe he has worth. Let’s keep the faith in prison reform, by keeping people of faith involved in prison reform.

Question 20: What’s next?

Henley’s prison release is set for March 28, 2031. At that point, he will be coming up on his 65th birthday. He is up for parole in 2029.

Who else wore No. 20 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

Luc Robitaille, Los Angeles Kings left wing (1986-87 to 1993-94; 1998-99 to 1999-2000; 2003-04 to 2005-06):

Best known: The greatest scoring left-winger in the game’s history with 653 goals and a first-ballot Hockey Hall of Famer could never skate away from his Los Angeles’ professional home base — Robitaille had three tours with the franchise, starting with a Calder Trophy in 1987 when he became the first (and thus far only) Kings player to win the NHL’s rookie of the year. A statue of him outside of Staples Center/Crypto.com Arena lists all his accolades — Most points (125) and goals (63) in season by a left wing (with the Kings in 1992-93), most consecutive 40-goal seasons by a left wing (eight, from 1986-87 through 1993-94), and Kings franchise records with most career playoff goals (41), most career regular-season overtime goals (5), most career points (1,137), goals (546) and assists (591) by a left wing, most goals in game (4, done twice in ’92 and ’93), most career playoff game-winning goals (9), most points (84) and goals (45) by a rookie in one season (1986-87), most goals in playoff series (8 vs. Edmonton in 1991 and most times named to a post-season All-Star team (8). All fairly staggering for the kid who grew up in Montreal, wasn’t the most fluent English speaker, and was a three-time winner of Los Angeles’ Most Popular Player (1987-88, 1991-92 and 1998-99), which gave the Kings even more reason to keep him on in their business department (when the team won the 2012 and 2014 Stanley Cup) and then elevated him to team president after his retirement.

After his first eight seasons, Robitaille was traded to Pittsburgh for Rick Tochett and a second-round pick used to get Pavel Rosa. The Kings got him back in 1997 from the New York Rangers for Kevin Stevens. Since Ray Ferraro had been wearing No. 20 for the Kings at the time, the story goes that Robitaille negotiated it for taking it back (and Ferraro taking No. 26) by sending Ferraro’s family on an Hawaiian vacation. After signing as a free agent with Detroit in 2001 and winning a Stanley Cup, Robitaille came back to L.A. for a third time in 2003 as a free agent and retired at 39 in 2006.

Not well remembered: In the 1984 NHL Entry Draft, the Los Angeles Kings spent a fourth-round pick on a high school center from Massachusetts named Tom Glavine, The team got around to picking Robitaille in the ninth round, 171st overall. Both ended up in a Hall of Fame — Glavine made it to Cooperstown by winning more than 300 games in Major League Baseball. Robitaille made it to hockey’s Hall in Toronto. The hockey experts actually thought Robitaille would be drafted much later. He was a poor skater, they said. The Kings were the only team that seemed interested in watching him during his junior career. As it happened, Robitaille attended the 1984 draft, sitting in the stands, and eventually introduced himself to first-year Kings general manager Rogie Vachon. Turns out, he and his eventual Kings’ teammate (and future team general manager) Dave Taylor are the lowest NHL draft picks to have recorded 1,000 career points.

Not well known: When Robitaille was entering his third NHL season in the summer of 1988, the Kings acquired his idol, Wayne Gretzky, in a trade with Edmonton. The Oilers wanted Robitaille in the deal. The Kings instead sent Jimmy Carson, the other rising star in the organization. Talk about the Luc of the draw.

Don Sutton, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1966 to 1980, 1988), California Angels pitcher (1986 to 1987):

Best known: Sutton was efficient enough to have 233 of his 324 lifetime wins (14th all time in the game’s history) come during 16 seasons with the Dodgers, and 28 more in three seasons with the Angels. Sutton’s retired jersey became part of the Dodger Stadium Ring of Honor following his 1998 induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame. Scuffmarks and all. It was said that when the Dodgers’ retired his No. 20, Sandy Koufax paid his way to be at the ceremony — they were teammates just one season, 1966, which was Koufax’s last and Sutton’s first. When Sutton thanked him for attending, Koufax said: “How could I not? You’re the only 300-game winner I ever played with.”

A four-time NL All Star with the Dodgers who was never the winner of a Cy Young nor on a World Series title team, Sutton was said to be fine leaving the Dodgers for a four-year, $3.1 million free-agent offer by Houston because he had got on manager Tommy Lasorda’s sore side. Sutton had been loyal to manager Walter Alston coming up in the Dodgers’ system pitching with Koufax and Don Drysdale — earning the nickname “Little D” — and lobbied to have his former catcher, Jeff Torborg, replace Alston as manager in 1976. Sutton was third in the Cy Young voting in 1976, but in the four years he pitched for Lasorda, he didn’t gain any Cy Young attention, despite leading the NL with a 2.20 ERA in 1980 before departing. Sutton had come back for one last go with the Dodgers at age 43 but departed early with a 3-6 record in 16 starts, during what would be the team’s 1988 title season. Sutton was the NL ERA leader with a 2.20 mark in 1980, his last full season in L.A., and his 2.08 ERA in 1972, the his first of four All-Star seasons, included nine shutouts. He recorded his 300th career win while wearing the Angels uniform in 1986. Trivia: He wore No. 27 with the Angels in 1985 and ’86 after Garry Pettis, who had No. 20, eventually switched to No. 24.

Not well remembered: No. 20 Sutton had only one 20-win season — gaining 21 in 1976. He also recorded nine 1-0 complete-game victories.

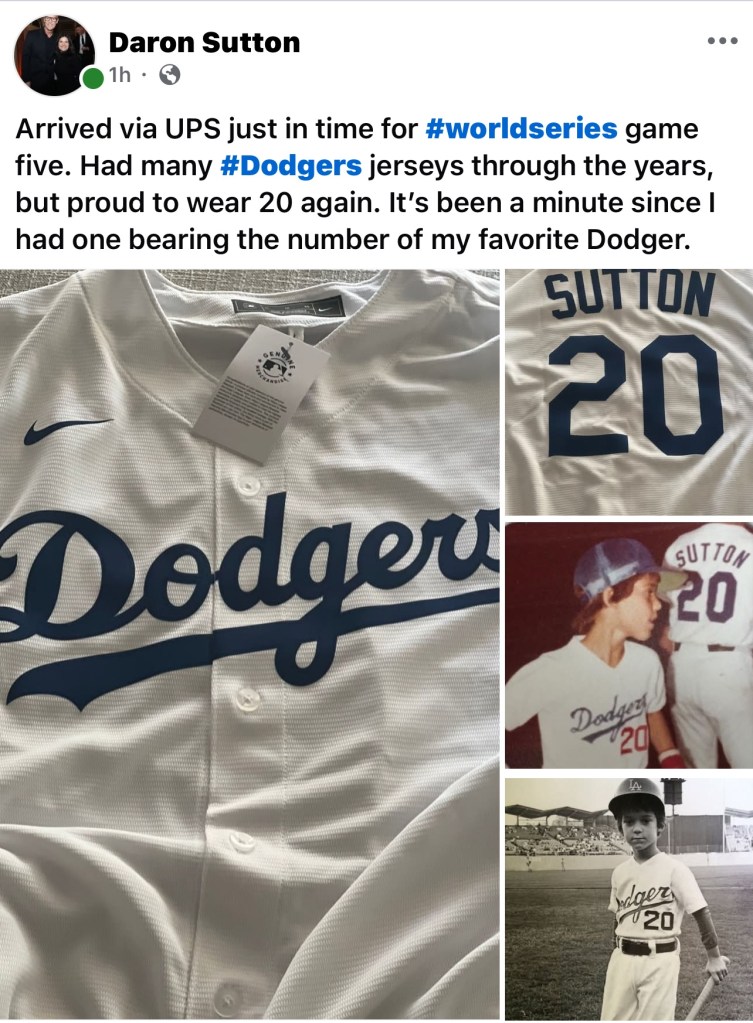

Also: As Sutton became an acclaimed MLB TV analyst/play-by-play man in Atlanta after his career, his son, Daron, also learned to be an MLB play-by-play broadcaster and was never far from No. 20.

Mike Garrett, USC football tailback (1963 to 1965) via L.A. Roosevelt High:

Best known: In ESPN’s 2020 list of the 150 greatest college football players in the game’s first 150 years, Garrett ranked No. 111. Noting his career marks of 3,221 rushing yards, 1,198 return yards and 30 touchdowns, it said: If USC is truly “Tailback U.,” Garrett launched the tradition by winning the school’s first Heisman Trophy in 1965. As a senior, Garrett led the country with 1,440 rushing yards with 17 touchdowns (two on punt returns). His career rushing total in three seasons broke a 15-year-old NCAA record. He also had 36 receptions, 43 punt returns, 30 kickoff returns, and threw six passes. In 1993, he was named USC’s athletic director, a position he held until 2010.

In his final home game at the Coliseum, a 56-6 win over Wyoming on Nov. 27, ’65, Garrett had three touchdowns, a 30-yard scoring pass and set the new all-time NCAA career rushing mark. At midfield after the game, USC president Dr. Norman Topping presented Garrett with his No. 20 jersey saying: “This is your traveling jersey. The one you have on is going into our Hall of Fame.”

Cal-Hi Sports named Garrett its best L.A. City running back (post World War II to present) to honor his outstanding career at L.A.’s Roosevelt High, where he was just 5-foot-8 and 180 pounds. After playing quarterback as an underclassmen, the Boyle Heights legend switched to tailback as a senior and was named Cal-Hi Sports State Player of the Year, aka Mr. Football, scoring 153 points in eight games on a team that lacked a lot of overall talent. “Talk about playing with 10 guys that basically got in the way,” said Bill Frazer, a L.A. City Section historian. “I saw Garrett three or four times and the other great SoCal backs of that area, they couldn’t hold a candle to Garrett.” He was the first L.A. City back to score six TDs in a game (against rival Garfield in the East L.A. Classic) and gained 1,467 yards on just 146 carries and finished his career scoring five touchdowns and two conversions against L.A. Wilson.

In 2002, Garrett, as the USC athletic director, approved having Long Beach Poly recruit Darnell Bing wear his retired No. 20. Bing went on to become an All-American in 2005, had eight career interceptions as a defensive back over three seasons and was drafted by the Oakland Raiders in 2006.

Not well remembered: In the 1966 NFL Draft, the hometown Los Angeles Rams picked Garrett in the second round (after taking offensive tackle Tom Mack from Michigan, the only eventual Pro Football Hall of Famer from that class, in the first round No. 2 overall). Garrett said he had been told he would be a first-round pick. So when the ’66 AFL Draft happened, Kansas City took Garrett seemingly as an afterthought in the 20th and final round. At the time, Garrett also was considering pro baseball based on his career in the sport at USC. Garrett, drafted in the first MLB Draft of 1965 by Pittsburgh in the 41st round, took it all into consideration and signed with the Chiefs. That got him to Super Bowl IV in 1970, where he had 39 yards rushing in 11 carries and a touchdown to help in the Kansas City win. After that season, Garrett said he would quit pro football and try baseball — the Dodgers, who had drafted him in the fourth round of the ’66 selection, came back and took him this time in the 35th round in 1970. When the Dodgers didn’t make him much of an offer, Garrett circled back to the AFL and the Chiefs traded him to the San Diego Chargers. At the end of that year, Garrett again said he was going to retire to play for the Dodgers, but he signed a two-year contract to stay in San Diego.

Frank Robinson, Los Angeles Angels DH (1973 to 1974): The future Hall of Famer regained the No. 20 he sported during his NL MVP career with the Cincinnati Reds and during his AL MVP career with the Baltimore Orioles. The Angels’ representative in the 1974 All Star game as a 38-year-old DH, Robinson was traded to Cleveland later that season, leading to his becoming the first MLB Black manager. Fifty of his 586 career homers came with the Angels.

Steve Bilko, Los Angeles Angels first baseman (1961 to 1962): The last two seasons of his MLB career came with the team that had the same name as the one starred with in the Pacific Coast League. The Angels took him prior to their first season off the Detroit roster in the expansion draft, hoping he would attract attention from his days at Wrigley Field. Also wore No. 33 and 36 for the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1958 and ’59.

Glenn McDonald, Long Beach State basketball (1971 to 1974): Elected to the school’s Athletic Hall of Fame in 1988. Had his number retired. An NBA draft first-round pick in 1974, McDonald came back to coach the 49ers women’s basketball program.

Steve Rucchin, Mighty Ducks of Anaheim center (1994-05 to 2003-04): After wearing No. 15 as a rookie, Rucchin switched to No. 20 and was often in the discussion for the Selke (top defensive forward) and Lady Byng (sportsmanship) Awards. He scored a playoff overtime goal in the Western Conference quarterfinals Game 4 against Detroit in 2003 to finish a four-game sweep.

Carlos Ruiz, Los Angeles Galaxy striker (2002-2004, 2008): Considered the greatest Guatemalan player in the country’s history, El Pescadito became the MLS Most Valuable Player in his first year with the MLS champion Galaxy, scoring a league-best 24 goals. In the playoffs, he scored eight goals and added two assists, totaling 18 points and setting an MLS record for goals and points in a single postseason, also scoring the OT game-winner in extra time for the Galaxy’s 2002 title. He was traded to Dallas in 2005 to make room for Landon Donovan’s return to the team.

Gary Payton, Los Angeles Lakers guard (2003-04): The future Basketball Hall of Famer put in one season in L.A. after his first 13 in Seattle, hoping to provide experience to the starting lineup with Kobe Bryant, Shaquille O’Neal, Karl Malone and Rick Fox. It led to the NBA Finals against Detroit. Payton was the only one to start all 82 games that regular season at age 35 and he led the team with 5.5 assists a contest while third in points at 14.6.

Have you heard this story?

Leon Wood, Cal State Fullerton basketball guard (1981-82 to 1983-84):

A 2007 Cal State Fullerton Hall of Fame bio notes that the 6-foot-3 was on the 1984 U.S. Olympic gold-medal winning team at the Los Angeles Games, a favorite of coach Bob Knight.

It was no small feat that Wood was an All-American on the same team as Michael Jordan, Hakeem Olajuwon, Sam Perkins, Chris Mullin and Wayman Tisdale.

But don’t overlook his career at Saint Monica High in Santa Monica. Wood averaged 33.7 points per game, rising as high as a staggering 41.5 points in his senior year, a state record.

After his freshman season at the University of Arizona, Wood came back to Southern California and set the Titans’ career record for points and assists. He led the nation with 319 assists as a senior, which set an NCAA record. Perhaps the Fullerton program’s greatest moment with Woods on the roster was an upset over No. 1 Nevada-Las Vegas, 86-78, at home in February of 1983, ending a 25-game Rebels win streak as Woods had 21 points and 12 assists.

A 10th overall draft pick by Philadelphia in 1984 — Wood figured he might go to his hometown Clippers at No. 8 — he had six seasons in the NBA, a teammate of Julius Erving and Charles Barkley, and played in the CBA and overseas before wrapping up his playing career in 1994.

It was an unlikely journey to retire and become a league referee, wearing No. 40. Note the headline to this story: “I won two gold medals with Michael Jordan, then called a travel on him during 28-year career as NBA referee“

In a 2018 interview with Forbes, Wood said: “I love basketball, something I’ve been doing since 5 or 6 years of age. I love every aspect of it. … I love being out there with the best athletes in the world. It’s just something I love. … This is something that’s just over-the-top different than what you normally do.”

Predictably, he found himself in a position where he had to decide whether or not to slap Barkley with a technical foul once.

“I can’t remember the exact game,” Wood said. “I didn’t say it, but it was almost that look like, ‘C’mon, don’t make me T you.’ And (he) was almost like, ‘You’re not going to T me.’ So I hit him, and he kind of chuckled, because it was like, ‘My ex-teammate just teed me.’ That’s how it felt.”

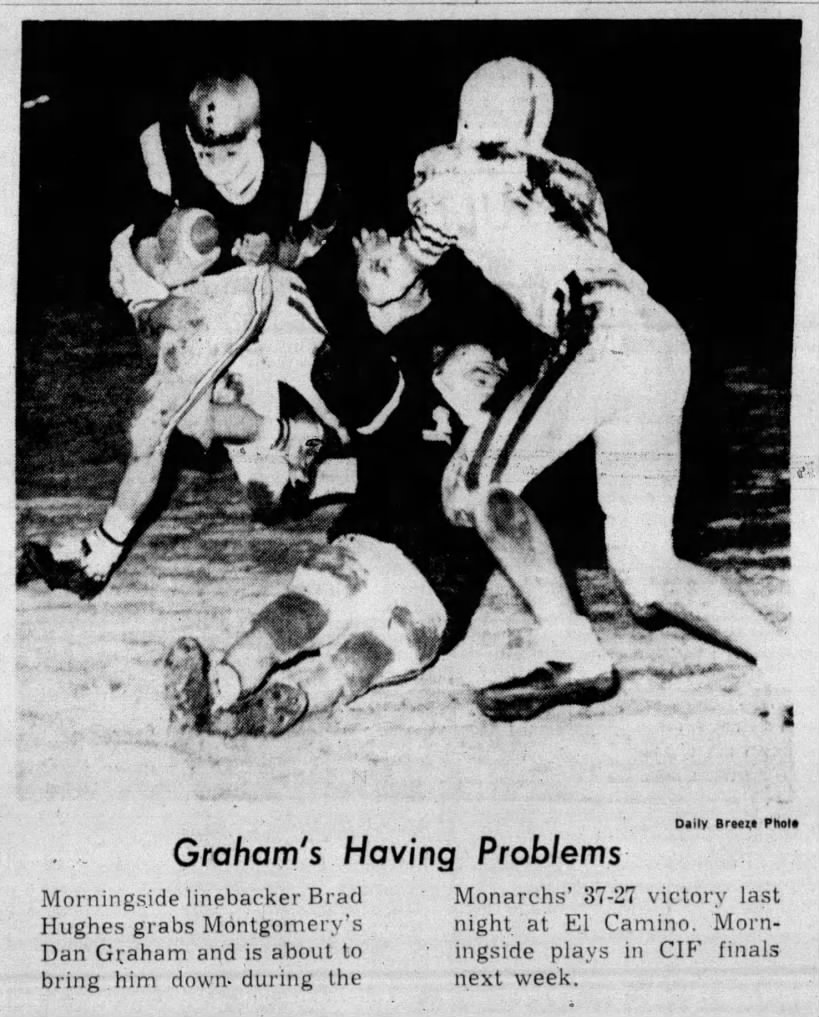

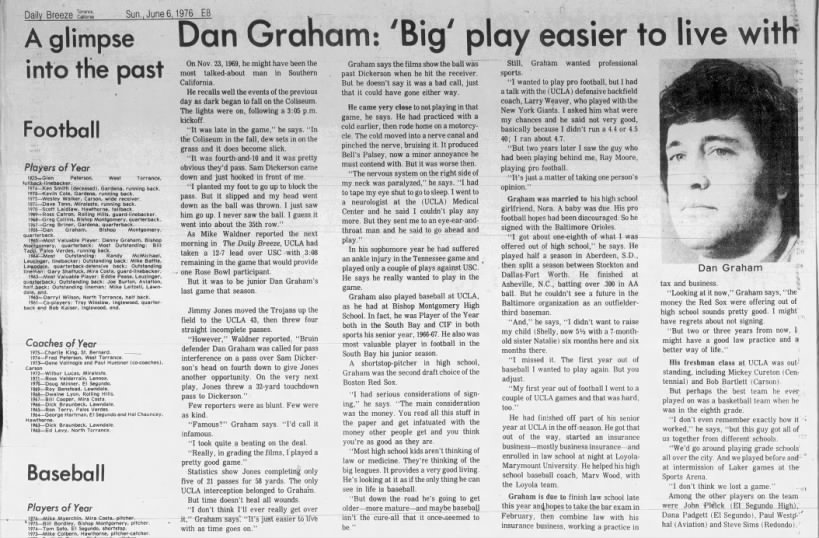

Dan Graham, UCLA football defensive back (1967 to 1969):

It’s fair to frame Graham’s career as a three-sport star at Bishop Montgomery High in Torrance, named CIF Player of the Year in both football and baseball as a senior, as one of the South Bay’s greatest athletes.

In football, he was the varsity quarterback for three seasons, throwing for 3,751 yard and 47 TDs. In baseball, he was a second-round draft pick by the Boston Red Sox in 1967, No. 23 overall as a shortstop — in the same draft where Baltimore took Long Beach Wilson’s Bobby Grich (No. 19 overall), St. Louis took heralded Torrance High pitcher Bart Johnson (50th overall) and Cincinnati took Torrance High catcher Fred Kendall (68th overall). Instead, Graham went to UCLA to play both football and baseball. His goal was to play pro football, even though he said the Red Sox offered him was a nice figure.

Moved to defensive back as a freshman for the Bruins, Graham ended up getting a mention in Sports Illustrated — but not for something he’d want to hang a career on. In a story recapping the USC-UCLA game in late-November game before 90,000 at the Coliseum in 1969, where both teams were 8-0-1, the first time both had come in undefeated since 1952, and a trip to the Rose Bowl was on the line as well as a possible national title, the famed Dan Jenkins wrote:

“It would be tempting to sit back and say that USC whipped the Bruins 14-12 on the biggest break since the San Francisco earthquake, meaning a pass interference call on a poor, sad, sick UCLA defender named Danny Graham, a play which gave USC a chance to come up with a winning touchdown pass in the game’s last two minutes. But actually that Wild Bunch of Coach John McKay had slowly been winning the game all afternoon by burying (UCLA quarterback Dennis) Dummit no less than 12 times when he was searching for a receiver—and intercepting him five times. …

“Here’s how it went for all of you television viewers who were lulled into a nap by the old-fashioned defense that flavored the day. USC had the ball on its own 32 with only those three minutes left and it had to pass, right? And Jimmy Jones had thrown 13 times so far and had completed only one—for one yard. Up in the press box a wit said, “Throw the one-yard bomb, Jones.”

“But Jones didn’t do that. He found an end for 10 and a first down. Then he threw to another end for eight. Then he hit a third pass, and the ball was across midfield. The clock had been rolling, though, and there were less than two minutes left. The UCLA defense … had shut down Clarence Davis, who entered the game as the nation’s leading rusher, giving him only 37 yards. And until now it had been scampering after Jones, harassing him into throwing the ball toward downtown. Jones, in fact, then proceeded to throw four straight incompletions from the UCLA 43, and the Bruins went berserk. The game was over. …

“There was only one thing wrong. Down on the UCLA 32 where a Jones pass for Sam Dickerson had missed him from Watts to El Segundo, a flag had fallen. UCLA’s Danny Graham, overanxious, had needlessly banged into the receiver as the ball sailed overhead. Interference.

“So on the next play, a thing called “60 play-action pass X-post on the corner” … Jimmy Jones drifted back and let go to the far right-hand corner of the dark end zone. Dickerson, a fast junior from Stockton, raced toward it, beating his coverage. The ball and Dickerson somehow met in a diving, falling, desperate instant—just six inches inbounds—and USC had made the Rose Bowl.”

Whether there should have been a pass-interference call on the first play, and a touchdown ruled on the second, depends on whether your vision is framed in cardinal red or powder blue, wrote the Los Angeles Times in 2009, going back 40 years later to review it.

“Around sunset, the Coliseum grass gets wet. No excuses, but my back foot slipped,” Graham said in the story about his involvement in that 4th-and-10 play that would have ended it likely with a win for UCLA. “Yeah, he could have caught it — if he were on stilts.”

The requirement that the pass must be “catchable” for an interference call was years in the future.

“The rules said it was pass interference at the time,” Graham said.

Graham said after the game, “It seems like my whole life just went down the drain.”

But he and his girlfriend went out and ate Chinese food in Santa Monica . . . and later married, and had three children.

In a 1976 story for the Daily Breeze, Graham said of the play: “I don’t think I’ll ever get over it.”

After UCLA, he tried to get back into baseball and made it as high as double-A with the Baltimore Orioles organization.

We also have:

Jalen Ramsey, Los Angeles Rams cornerback (2019 to 2022)

Brian Shaw, Los Angeles Lakers guard (1999-2000 to 2002-03)

Don Nelson, Los Angeles Lakers forward (1963-64 to 1964-65)

Maurice Lucas, Los Angeles Lakers forward (1985-86)

Rip Repulski, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (1959 to 1960)

Gary Pettis, California Angels outfielder (1983 to 1986). Also wore No. 30 in 1982 and No. 24 in 1986-87.

Phil Nevin, Anaheim Angels infielder (1998)

Anyone else worth nominating?

2 thoughts on “No. 20: Darryl Henley”