This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 83:

= Willie “Flipper” Anderson, UCLA football, Los Angeles Rams

= Ted “The Mad Stork” Hendricks, Los Angeles Raiders

= Richard “Batman” Wood, USC football

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 83:

= Jimmy Gunn, USC football

= Cormac Carney, UCLA football

= Willie Hall, USC football

The most interesting story for No. 83:

= Cormac Carney, UCLA football wide receiver (1980 to 1982)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Long Beach, Westwood, Santa Ana

Judging by Cormac Carney’s commitment to competent jurisprudence compiled over three decades until his retirement in May of 2024, you’d think the one-time UCLA wide receiver would be satisfied with his dedication to public service.

On on scale, President George W. Bush thought enough of Carney to nominate him as a U.S. federal district judge, receiving unanimous approval by the U.S. Senate. It was a promotion after just two years as a California state superior court judge.

On the other side, Kamala Harris once thought enough of Carney to wonder what the heck he was thinking when he tried to apply the U.S. Constitution’s Eighth Amendment to a particular death penalty case that seemed to usurp her role as the California attorney general. California Governor Gavin Newsom thought the same when his bill limiting handgun ownership was squashed by Carney, citing the Second Amendment.

The catch here: Carney had an overarching dream to be a football player. But as he compiled 108 catches for 1,909 yards and eight touchdowns during three seasons as UCLA –leaving the program as a career leader in several categories in the early 1980s — Carney was also a three-time Academic All-American and nominated for a Rhodes Scholarship.

There are notable examples of footballers-turned-adjudicators — Byron “Whizzer” White, the University of Colorado’s first All-American who is not only in the College Football Hall of Fame but served more than 30 years as a U.S. Supreme Court justice; Alan Page, the first African-American to become a Minnesota Supreme Court judge after his NFL Hall of Fame career as a defensive tackle with the Vikings.

Then there was Cormac Carney, a name best suited to describe an overloaded chili dog special on the menu at Barney’s Beanery.

Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray once wrote: “(His name) is like a diesel train. You can’t tell which is the front end. You can’t tell whether it’s coming or going. … Is it a real name? You roll it around on your tongue like an Elizabethan iamb.”

His teammates were apt to call him “Cormac the Magnificent,” riffing off the character that “Tonight Show” host Johnny Carson used for his running joke of the fortune teller “Carnac the Magnificent.”

Carney made a name for himself in Westwood and that helped if he was ever full of beans while grilled by the media, or later challenged by an appellant court just for one of his many rulings.

Carney was born in Detroit to parents who were medical doctors studying together in their native Ireland. His father, Padraig, was also a champion player in Gaelic football during the 1950s and is in the Gaelic Athletic Assn. Hall of Fame.

“Cormac was the last high king of Ireland, I’m told,” Cormac Carney once said.

The family matriculated to Southern California. Cormac, the youngest of three boys, followed his brothers at St. Anthony High School in Long Beach playing football (as No. 82) and basketball, but he found few if any college recruiters interested. The teams Carney played on were hardly conference contenders.

“What I was at St. Anthony, the only thing I worried about was playing football,” Carney told the Long Beach Press-Telegram in 2008, 10 years before he would be inducted into the school’s Athletic Hall of Fame. “It was the only thing I thought about and wanted to do.”

The 5-foot-11, 200 pounder didn’t want to stick around and try a junior college,so he gravitated to the Air Force Academy in 1977, where older brother Brian was to play his senior season (and later went onto become an orthopedic surgeon).

After sitting a year, Carney wore No. 83 and set an NCAA record for freshmen with 57 catches (second most in a season at the program’s history), 870 yards and eight touchdowns. His best game, and one of the most prolific still in school history, was 11 catches for 220 yards for the Falcons against Georgia Tech.

Just one problem: Carney discovered he had motion sickness trying to fly planes.

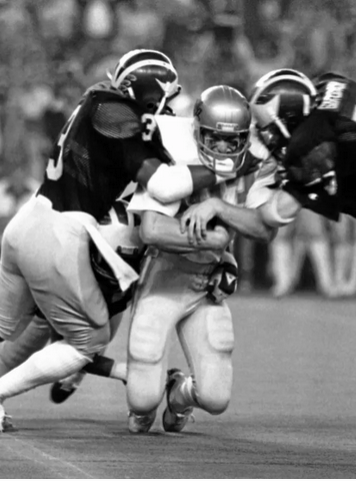

He flew back to Southern California and grounded himself. After sitting out the 1979 season as a transfer and playing on the scout team, he finished with three years at UCLA — twice named to the All-Pac-10 teams and helping Terry Donahue’s fifth-ranked UCLA squad post a 24-14 win over Bo Schembechler’s Michigan team in the 1983 Rose Bowl.

Carney, who made two catches in the Rose Bowl for 33 yards, turned out to be the Bruins’ top receiver and set single-season records as a senior with a team-high 44 catches for 746 yards from Tom Ramsey. Carney may not have had the speed of teammate Jojo Townsell or the the target height of tight end Paul Bergmann, but he stood out as a reliable target on a corps that also included underclassmen Harper Howell, Dokie Williams and Karl Dorrell. UCLA started that season ranked No. 20 before moving up the polls each week compiling an 10-1-1 record, with a regular-season 31-27 win at Michigan as well.

Carney once told Los Angeles Times columnist Scott Ostler that his day at UCLA would often be during the summer: Working 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. at a mortgage company, football practice from 4 to 6:30 p.m., tutoring other students from 7:30 to 10:30 p.m.

“Tutoring taught me so much,” he said. “I realized how lucky I was to have parents who made sure I got a quality education. I’ve learned that some public schools are doing a really poor job. I also learned that some kids with academic problems have a better attitude than I do. … They work their butts off and I think it’s fantastic they’re given an opportunity to go to UCLA.”

The winner of the Jack R. Robinson UCLA Football Team Scholastic Achievement Award, the highest scholarship for a senior player, Carney was also given the UCLA All-Around Excellence Award for his character, leadership, and sportsmanship. In 1982 he was named Long Beach Century Club’s Athlete of the Year.

But his name wasn’t called in the NFL draft.

“I’m sure they just didn’t think I was fast enough,” Carney told the Los Angeles Times, as it had been noted he had a 4.9 time in the 40 yard dash. “That was what people said when I came out of high school. I proved a lot of people wrong then, but, who knows? Maybe this time they’re right. But maybe they’re not. … To be honest, I thought I would be drafted. I’d be lying to you if I said it didn’t hurt a bit. … I believe in fate. For some reason, I wasn’t supposed to be drafted.”

The USFL’s Los Angeles Express did choose him in its inaugural draft, but as an 11th round choice. The New York Giants gave him a tryout, only to have coach Bill Parcells (who had coached him at the Air Force Academy) to cut him after two exhibition games. He turned down an offer to tryout for the San Francisco 49ers.

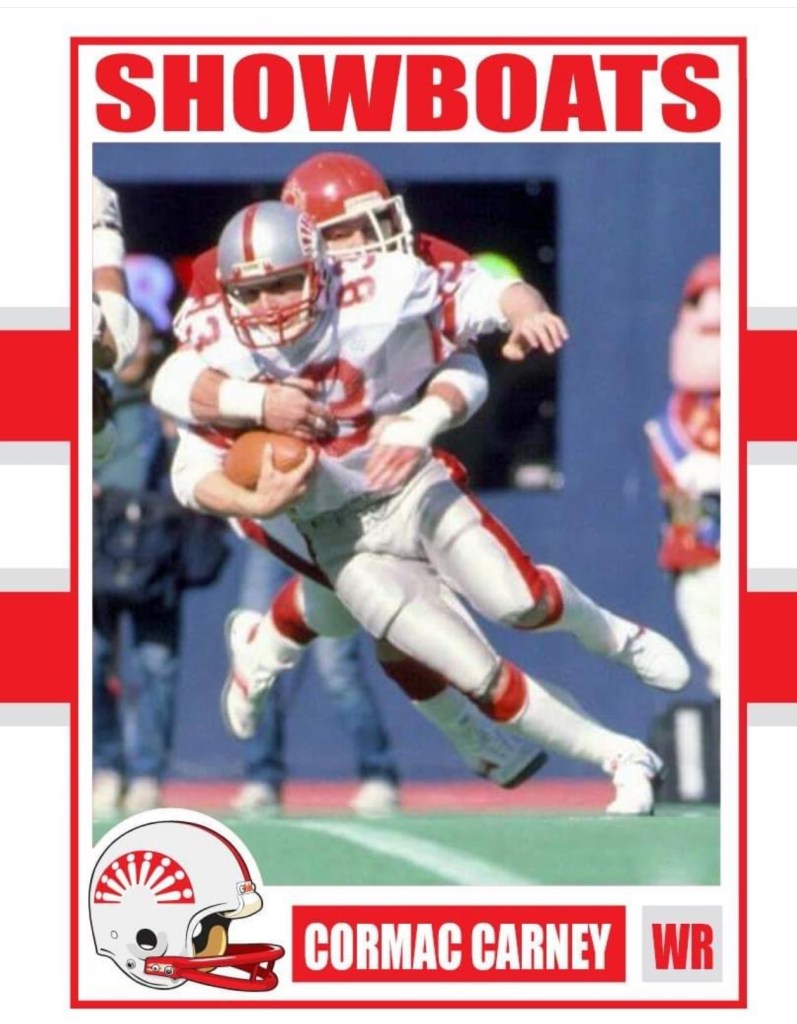

Eventually, he caught on with the USFL’s Memphis Showboats (still wearing No. 83), coached by former UCLA head man Pepper Rodgers (and a good friend of Donahue). Carney pulled in 37 catches for 701 yards and two touchdowns and returned five kickoffs for 74 yards.

And that was that. But the beauty of it — Carney said the money he made in the USFL paid for nearly two years of his Harvard Law School education, where he met his future wife, Mary Beth, and got his Juris Doctor degree in 1987.

He started in the law firm of Latham & Watkins for four years, followed by 11 more at O’Melvney & Myers, doing business litigation. Warren Christopher, the U.S. Secretary of State, had been Carney’s legal mentor. Christopher was a longtime friend of former USC football player and Los Angeles City Councilman John Ferraro from their days serving on a tanker with the U.S. Navy.

In October of 2001, California governor Gray Davis appointed Carney as an Orange County Superior Court judge, preceding over civil and criminal cases.

Two years later came President Bush’s appointment of Carney to become a U.S. District Judge, Central District of California, Santa Ana Division. He knew he had to ignore “those who thought he was too young and inexperienced to succeed” after he was confirmed by the Senate in April of 2003 just before his 34th birthday.

Carney’s first two years in the role included cases where he upheld a death penalty ruling against a man accused of killing a 12-year-old girl in the Cleveland National Forest in 1981, convicted men of smuggling women into the country and forcing them into prostitution, and handling a multi million-dollar patent case. He would also rule in favor of a Washington Times reporter withholding the names of his sources, but also sentenced a 60-year-old Ponzi schemer to a 30-year prison term.

Then came even more notable, controversial and headline-grabbing decisions:

= 2009: He dismissed all fraud and conspiracy charges related to stock options backdating against Broadcom Corporations William Ruehle and Henry Nicholas on grounds of prosecutorial misconduct involving witness intimidation.

Carney also vacated a guilty plea by Broadcom co-founder Henry Samueli, owner of the NHL’s Anaheim Ducks. Added to that, Carney dismissed a civil case by the SEC against the Broadcom execs.

“You are charged with serious crimes and, if convicted on them, you will spend the rest of your life in prison,” Carney explained at the time. “You only have three witnesses to prove your innocence and the government has intimidated and improperly influenced each of them. Is that fair? Is that justice? I say absolutely not.”

= 2010: He was the first federal judge to convict someone under the Economic Espionage Act. Carney sentenced Donfan “Greg” Chun, a Chinese-born space engineer to nearly 16 years for stealing secrets related the U.S. Space Shuttle Program.

= 2011: He sanctioned the FBI after finding an agent lied about the existence of documents in a civil case of an Islamic group, then dismissed a related lawsuit at the FBI’s request to protect national security.

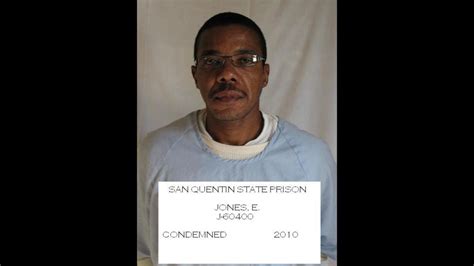

= 2014: He vacated the 1995 death row sentence of a Ernest Dewayne Jones, convicted of rape and murder, declaring the state’s death penalty violated the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment.

He wrote: “The dysfunctional administration of California’s death penalty system has resulted, and will continue to result, in an inordinate and unpredictable period of delay preceding their actual execution. Indeed, for most, systemic delay has made their execution so unlikely that the death sentence carefully and deliberately imposed by the jury has been quietly transformed into one no rational jury or legislature could ever impose: life in prison, with the remote possibility of death.” At that point, California reinstituted the death penalty in 1978 but only 13 of the 900 inmates scheduled to be executed had taken place.

In short, Carney ruled the state failed to live up to its “promise” to Jones to execute him.

Thus entered Kamala Harris, then the California state attorney general, and said Carney’s decision as “flawed.” She made an appeal to the 9th Circuit Court, and in 2015 it overturned Carney’s ruling on procedural grounds. Carney later called that reversal “disappointing and sad.”

= 2017: He threw out much of the evidence in a case where FBI agents were notified of alleged images of child pornography on the computer of a Newport Beach doctor by Best Buy computer-repair technicians. Carney determined an FBI agent had made “false and misleading statements” while seeking a search warrant of the defendant’s home.

“A person’s home is sacred to me,” Carney said. “And I’m not trying to get on my high horse, but, you know, close is not good enough for me when you’re asking to search someone’s home.”

= 2018: He dismissed charges against a defendant who claimed he was unfairly targeted by Orange County Sheriff’s Deputies after attempted murder allegations against him in state court were dismissed in the midst of the jailhouse informant scandal.

Carney questioned why federal prosecutors were filing charges involving such a small amount of drugs — 37.7 grams of methamphetamine — particularly in the midst of a then-active federal investigation into the use of snitches in Orange County.

“I am absolutely baffled the government charged this case and pursued it, particularly with the baggage of the witnesses,” he told prosecutors at the time.

= 2019: He dropped all conspiracy incitement charges against an alleged white supremacist, Robert Rundo of Huntington Beach, and those in his group, Rise Above Movement, saying the defendants in a beating case of a journalist at a 2017 political rally at UC Berkeley as well as a beating care at Bolsa Chica State Beach that year were unfairly prosecuted in the grounds that the equal protection component of the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment does not allow the government to arrest members of one political group and not another. Rundo was arrested again but allowed to leave jail in 2024.

“I’m a big believer in the rule of court, so I would like to be in a position to release him right now, let him walk out that door, but I can’t do that because the 9th Circuit told me I can’t,” Carney said after Rundo was re-arrested. “It bothers me. It doesn’t matter whether Mr. Rundo is a good man, a bad man, whether he did something wrong here or not. We’re all entitled to our Constitution and no one’s following the rules and I’m at a loss to understand it.

“People can disagree with my decision,” he said. “I respect that. You can take me up (to the appellate court). The 9th Circuit can criticize me. God knows they have done it enough. But throwing out fundamental rules of criminal procedure and going out to arrest someone without pending charges, that’s frightening to me.”

= 2020/21: He was outspoken about how trial should continue during the COVID-19 pandemic and sought to summon jury pools for trials, but had the effort blocked by a chief justice. In five criminal cases, Carney dismissed federal charges saying there was prejudice on speedy trial grounds, leading to more appeals by the 9th Circuit, which reversed his dismissals because it said Carney misread certain provisions in the “speedy trial” act.

Prosecutors argued that Carney had “weaponized” the cases he dismissed in order to “combat his colleagues” on the bench who were taking a more cautious approach.

= 2021: He sentenced an Ontario men to three years in federal prison for operating an unlicensed business that exchanged at least $13 million in Bitcoin and cash that was a conduit for money laundering of drug trafficking proceeds.

= 2022: He denied a motion to dismiss a lawsuit filed by five homeless residents and a non-profit organization against the city of San Luis Obispo, contending the unhoused individuals were treated unlawfully for living outdoors. Attorneys for the city fought for its right to enforce health, safety and environmental protection ordinances.

= 2023: He blocked major parts of a California law just days before it would go into effect on Jan. 1, 2024, which barred licensed gun holders from carrying their firearms into an array of public places.

Calling the law unconstitutional, Carney wrote that its coverage “is sweeping, repugnant to the Second Amendment, and openly defiant of the Supreme Court.” California Gov. Gavin Newsom, who signed the bill into law and has called for tougher gun restrictions in the state and at the national level, immediately swung back with his own statement in defense of the measure.

“Defying common sense, this ruling outrageously calls California’s data-backed gun safety efforts ‘repugnant,’” Newsom said. “What is repugnant is this ruling, which greenlights the proliferation of guns in our hospitals, libraries, and children’s playgrounds — spaces which should be safe for all.”

Carney pushed back, saying the new law went too far and focusing new gun restrictions on people who have permits to carry guns in the state made little sense from his perspective.

“Although the government may have some valid safety concerns, legislation regulating [concealed carry] permit holders — the most responsible of law abiding citizens seeking to exercise their Second Amendment rights — seems an odd and misguided place to focus to address those safety concerns,” Carney wrote.

= 2024: Even though defendant Tyler Laube confessed to beating a journalist at that ‘17 political rally and pleaded guilty to violating riot laws as part of a white supremacist gang, Carney sentenced him to just 35 days, time served, instead of six months that the prosecution sought. Carney said giving Laube more punishment “would only increase the disparity” between what Laube served and “the lack of punishment (and prosecution) members of far-left groups who have committed the same violent conduct.”

“He’s really gone off the deep end,” said John Donohue, a professor at Stanford Law School, said of Carney.

Carney had said several times that his years playing football gave him plenty of experience on how to endure the hard knocks of judicial decision making.

“(Football at UCLA) reinforced that principle that you can achieve great things if you work hard and are at the right place at the right time,” he told the Orange County Register in 2003.

In 2006, Carney, who got his undergraduate degree, cum laude, from UCLA in psychology, also said: “From a very, very early age, all I wanted to do was play football, but at every turn they said I just didn’t have what it takes. My athletic experience really has helped me deal with courtroom pressure.”

His former coach Donahue agreed.

“All of the things he learned in football related directly to what he’s doing now,” Donahue once said. “Both environments are demanding and call for discipline and commitment.”

Carney, who in 2008 received the NCAA Silver Anniversary Award which recognizes former student-athletes who excel in their chosen profession following their college career, said he far more enjoyed the life of a judge than of a lawyer, which was a means to an end.

“As lawyer, your focus is to win. Your whole purpose as a judge is to do the right thing. You get to see people’s greatest ideas and business strategies. You also see the worst in humanity. … I knew this job would be interesting, but I really didn’t appreciate what high-stakes stuff I’d be dealing with week in and week out.”

One of the most endearing stories involving Carney was reported by the Washington Post about his presiding over a U.S. naturalization of some 3,200 immigrants at the Los Angeles Convention Center in August of 2019.

One of the attendees, a 31-year-old Armenian American named Tatev (she only gave her first name), was reported to be nervous at then-President Trump’s hard-line stance on immigrants and, fearing she would lose her green card, she was determined to not leave the event until she could official become a citizen having already spent six years going through the process. Oh, she was also nine months pregnant and having contractions.

Carney saw what was happening and devised a creative solution: He found Tatev in the corner of the Convention Center and “preformed an impromptu naturalization ceremony just for her … (she) raised her right hand, swore an oath, and became official.

On May 31, 2024, the Daily Journal ran a story headlined “An Iconoclastic Judge Takes A Bow.” The subhead read: “For two decades, U.S. District Judge Cormac Carney of Santa Ana ruffled feathers.”

The story said Carney’s career was “marked by maverick decisions.” He was “a straight talker.” One colleague called him “incredibly courageous.”

It only briefly highlighted an incident in 2020 when Carney stepped down as chief judge of the Central District of California after a controversy when he used the term “street smart” to describe an African American clerk during a webinar. Carney apologized, but it didn’t end peacefully. It was pointed out that Carney also told this experienced clerk, Kiry Gray, that: “At least I did not put my foot on your neck like the police offers” in the aftermath of the George Floyd murder.

Carney was only on the bench 25 days as the Chief Judge of the Central District of California because of that controversy.

John Hueston, a former federal prosecutor who once had a trademark infringement trial in Carney’s courtroom in 2003 and once led the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Orange County, once said Carney was a “passionate man with a very strong internal compass … Beware the attorney who attempts to fiddle with Judge Carney’s finely-tuned sense of justice.”

In a statement that appeared in the Daily Journey, Carney was quoted about his career:

“Over 21 years ago, I made a solemn promise to support and defend the Constitution and the laws of the United States. My sincere thanks to all the wonderful people who have helped me keep that promise. In the words of Saint Paul, we fought the good fight, we finished the race, we kept the faith.”

The Journal added that Carney’s statement “sounded like a mic drop.”

Which, in perspective, is much better a drop of a pass over the middle in a critical bowl game.

Who else wore No. 83 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

Willie Anderson, UCLA football receiver (1984 to 1987); Los Angeles Rams receiver (1988 to 1994):

They called him “Flipper,” a nickname given to him by his Aunt Pearl who was babysitting him and thought he cried like the dolphin on TV with the same name. A big-play receiver who averaged 19.4 yards a catch in college and 20.1 per catch in the NFL, it noted that the first game he started at UCLA against Stanford in October of 1985, he caught five passes for 100 yards, including a 51-yard touchdown, as he battled for time as Troy Aikman’s favorite target with Mike Sherrard and Karl Dorrell. Anderson had eight games with at least 100 yards receiving – the most in school history — when the Rams drafted him in the second round of the 1988 selection.

His Rams career was marked with an exclamation point in 1989 when he surprisingly established the all-time NFL single-game receiving record of 336 yards on 15 catches during a Week 12 nationally televised Sunday night game in New Orleans, capping a 20-17 Rams overtime win — a field goal set up by a 26-yard reception from Jim Everett. Anderson only started that game because of an injury to Henry Ellard. On a Super Bowl week episode of “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?” the it came up as the $125,000 question — “What NFL player holds the record for most receiving yards gained in a single game?” The absurdity of that game performance was even analyzed in a piece by FiveThirtyEight.com.

Later that season, Anderson had a game-winning 30-yard catch in overtime as the Rams took a 19-13 win over the New York Giants in an NFC divisional round game. He finished his NFL career with 267 catches for 5,357 yards (20.1 yards-a-catch average) and 28 touchdowns.

Ted Hendricks, Los Angeles Raiders left outside linebacker (1982 to 1983):

The 6-foot-7, 220-pounder born in Guatemala and known as “The Mad Stork” spent the last nine years of his NFL career was with the Raiders, and the last two with the franchise were when the team moved to Los Angeles — and he remained a Pro Bowl selection those two seasons at age 35 and 36. He wore No. 83 when he debuted with Baltimore in 1969 and retained it when the Raiders got him in 1975. As a result, the Pro Football Hall of Famer and eight-time Pro Bowl pick was named to the NFL’s All-1970s Team and its All-1980s Team. Also to note: In ESPN’s 2020 list of the 150 greatest college football players in the game’s first 150 years, Hendricks ranked No. 85 for his days at Miami, and the Ted Hendricks Award has been given out since 2002 to the best defensive end in college football.

Jimmy Gunn, USC football linebacker (1967 to 1969):

Out of L.A.’s Lincoln High, Gunn became part of the Trojans’ “Wild Bunch” that allowed just 2.3 yards per carry in the 1969 season as USC finished 10-0-1. Part of three Rose Bowl teams, the All-American and two-time All-Pac 8 first teamer was the team’s Lineman of the Year in ’69. He was inducted into the USC Athletic Hall of Fame in 2001. Gunn also played seven NFL seasons.

Willie Hall, USC football linebacker (1970 to 1971):

The two-year starter and second-team All-American as a senior, Hall was part of the ’70 USC football team that went to face Alabama as part of the first racially integrated team. In the season finale against Notre Dame, Wood had eight unassisted tackles and was named Player of the Game. A member of the Trojan track team, Hall was named by teammates as the ’71 MVP and received the Gloomy Gus Henderson Award for most minutes played. He was a second-round NFL draft pick by New Orleans and lasted six seasons, the last four with the Oakland Raiders, playing in Super Bowl XI at the Rose Bowl and making a key fumble recovery that led to the Raiders’ first score.

Richard Wood, USC football linebacker (1972 to 1974):

The black paint smeared around the eyes and nose of the 6-foot-2 and 224-pounder led to his nickname of “Batman.” During freshman orientation at the famed Julie’s Restaurant off campus, the New Jersey recruit tried to lighten the mood when he stood up and said: “I’m Batman from Gotham City.” As his College Football Hall of Fame bio notes for his 2007 induction, Wood was USC’s first three-time All-American and a key member in two national championship teams. Wood not only led USC in tackles as a sophomore, but the next-closest teammate was 30 behind him. Calling defensive signals, Wood had 18-tackle games against UCLA and Arkansas. Among his five interceptions was returning one for a touchdown. As a junior, Wood had another trip to the Rose Bowl and an 18-tackle game against Notre Dame. By his senior year, Wood was part of another national title team, another Rose Bowl win and closed his career as the teams he was on finished 31-3-2. A third-round draft pick by the New York Jets, Wood spend most of his career under John McKay at Tampa Bay in the NFL. In a 2020 poll by the New York Times to determine the “best players to wear every jersey number in college football history,” Wood was the top pick for No. 83, ahead of Missouri’s Kellen Winslow, Notre Dame’s Jeff Samardzija and Ohio State’s Terry Glenn.

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 83: Cormac Carney”