Updated: 12/23/25

This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 87:

= Danny Farmer, UCLA football

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 87:

= Ralph Haywood, USC football

= Billy Truax, Los Angeles Rams

The most interesting story for No. 87:

Rob Gronkowski, retired NFL player, mascot for the LA Bowl (2023 to present)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Inglewood (SoFi Stadium), Hollywood

College football’s December-not-so-much-to-remember bowl season — all those exhibitions with goofy sponsors that provide TV programming for habitual gamblers leading up to what happens closer to New Year’s Day — is really bucked up.

And, yes, we’re looking directly at the official dummkopfs associated with the LA Bowl (2020 to 2025).

It exists inside the terrarium spaceship that landed upon Inglewood, clinging to a mixed-up premise as to what programs/conferences qualify, and it goes down with a title sponsor of something people buy to willingly ingest called Bucked Up.

And as the malfeasance maitre d, Rob Gronkowski has had to wear it.

Aka “Gronk,” the human Spuds McKenzie/playfully harmless retired NFL tight end who wore No. 87. Best known as Tom Brady’s lifeline on a short- yardage play near the end zone and his foil in public televised roasts.

Even though he flies in every weekend to goof it up on Fox’s NFL Sundays studio show from Century City, we’re not sure Gronk could really point to L.A. on a map and be confident it had it correct.

As a result, Gronk became one of the poster children for the ultimately mangled and maligned college football season, putting in him a police lineup with a Pop Tart, a Bad Boy Mower a giant vat of mayonnaise.

In 2014, someone named Lacey Noonan wrote an erotic novel called “A Gronking To Remember.”

Jimmy Kimmel invited Gronkowski onto his late-night show in Hollywood to read excerpts of it aloud.

Just go to Chapter One:

As it has turned out, both Kimmel and Gronkowski have helped make the LA Bowl a Gronking to forget.

From its ominous start to its fizzled-out finish.

College football has bought into a rather unhealthy exercise allowing more than 80-some programs that finished the regular season with a .500-or-better record to prolong the risk of injury and break free of campus finals to participate in what’s been called the Bowl Season.

From soup to nuts, adding and subtracting from its lineup as sponsors and cities come to realize it can’t possibly make up the money to fund it, what may have been couched as a reward for the players of the programs to NCAA-approved take home bag-loads of graft as a way for the unpaid amateurs to sell it off for a meal and a movie ticket at some point as Christmas came and went had quickly devolved into something more disposable than an Sears Holiday Wish Bo0k.

At this point, it makes more and more sense to players, as well as administrators who can’t sell tickets to its alum base, to just pass on this “opportunity.” Preserve the player’s health and perceived value going forward. Now, programs welcome a chance to pause and, perhaps, fire and hire another coach. It also avoids showcasing what’s left of the roster to competing programs, enticing on-the-fence players to enter the transfer portal for the promise of more playing time and a better NIL deal.

As for the cities hosting these games, they may pencil out a redeeming business plan of having nearby-by hotels filled and sight-seeing tours planned to please their departments of tourism, but the loss-leader aspect of this seems more and more cautionary with the red ink.

The 2025 CFP campaign stretched the limits of controversy again. In expanding from what was initially a four-team add-on schedule to try to crown a national champ, it has tried to appease sore losers by accommodating at 12-team format for those deemed worthy enough to endure a gauntlet of more high-pressured games. That means we now have 11 games involved in this bracketed affair between Dec. 19 and Jan. 19, 2026, and the CFP hijacks/compromises the otherwise traditional Rose, Fiesta, Peach, Sugar, Cotton and Orange Bowls partnerships — The Big Six as they call ’em– to help the perception of keeping history important.

That means, in what has become the NIT of the CFP, there are 36 bizarrely sponsored bowl games also happening, and overlapping, between Dec. 13 and Jan. 2.

In 2025, Notre Dame was snubbed by the CFP committee, and the Irish got their Irish up and declared there was no consolation trip necessary for them. It’s CFP or bust. More followed suit, seeming granted permission now to do what they’d wanted to do anyway. Iowa State and Kansas State, both bowl eligible, became bowl defiant. Even a gaggle of 5-7 replacement teams with branding power like Florida State, Auburn, Central Florida, Baylor, Rutgers and Temple declared themselves disinterested.

So we land on The LA Bowl, in whatever context it is branded, essentially kicked to the curb.

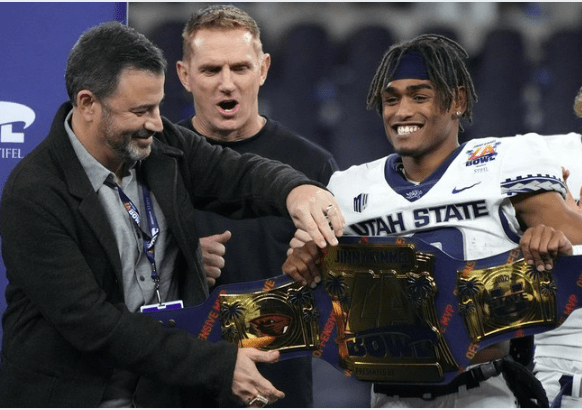

The Bucked Up LA Bowl Hosted by Gronk played its swan song on Dec. 13 before a national ABC audience that just watched the Heisman Trophy ceremony. The Washington Huskies (8-4, 5-4 in the Big Ten, tied for seventh) defeated the Boise State Broncos (9-4, 6-2 in the Mountain West, tied for first) by a 38-10 count. Attendance was listed as 23,269.

The Idaho Statesman explained: “Blitz the tee dog easily outran game host Rob Gronkowski in their race Saturday night. That was just about the only highlight for Boise State. In what was said to be the final LA Bowl, the Broncos didn’t quite have a night to remember in sparsely populated SoFi Stadium.”

When it was done, the stadium crew had to clean up the venue quickly for the next afternoon’s far-more-influential Rams-Lions NFL game.

By that point,the Gonzo Gronk Brand Party + Football Funday was nothing more than a disheveling hangover.

This particular non-essential addition to the otherwise prestigious history of Southern California college football bowl games was problematic since someone dreamed it up for what was the somewhat aborted 2020 season.

First issue: The name. Is it “LA,” without the periods? Or “L.A.” as one might assume as an abbreviation for the county that includes the game site? LA-de-da, it all seems.

The first LA Bowl was supposed to happen on the eve of New Year’s Eve on 2020, but that idea was squashed. Anxiety from the COVID pandemic may be the official reason, but a rabid college bowl contamination virus seems more realistic. There wasn’t enough vaccine cultivated at that point to make it safe for future generations.

The LA Bowl mutated into quite some sort of low-brow spectacle meant to be an easy neutral-site road trip for the champion of the Mountain West Conference, which kept getting ghosted by any sort of CFP format, to see how it measured up against the fifth-place team from the Pacific 12 Conference.

Funny thing … the Pac-12 disappeared in front of them. When eight teams followed the lead of USC and UCLA escaping a perceived botched financial alignment, and a musical-chairs money grab ensued, by the time 2024 happened, just Washington State and Oregon State were conference members, the only ones seemingly unable to muster the courage to depart.

LA Bowl organizers had to modify its requirement to keep the MWC opponent as something called a Pac-12 “legacy” team.

In ’25, Washington carried that “legacy” burden. But by 2025, the Pac-12 would be expanding back up to eight teams — luring in MWC members Boise State, Colorado State, Fresno State, San Diego State and Utah State, plus Texas State from the Sun Belt.

Which effectively guts the MWC, right?

See where this isn’t going?

The LA Bowl started with what seemed to be a lark quickly linked up to Kimmel’s LinkedIn account as well as giving ABC’s lineup of programming some synchronicity.

After the 2020 false start, the game went back on the 2021 schedule. Kimmel allowed his bosses to brand his name on it like how old PGA Tour events of the 1960s had celebrity names attached. One of the perks for the participating teams coming to L.A. was a visit to a “Jimmy Kimmel Live!” show taping on Hollywood Blvd., amidst weirdos in Superman costumes trying to bum a couple bucks for photo ops with tourists outside the front doors.

Bravo (?) to Kimmel’s creative team in creating a more dysfunctional attraction-seeking element of that first game — “Jimmy Camel,” a vomit-on-demand keepsake. Very reflective of those who felt queasy about this whole deal.

Kimmel may have got this game over the hump with his association, but it only lasted two seasons where he got to play the game off blowing into his clarinet while marching in the 2022 halftime show with Washington State.

Team Gronk then cannonballed in. No mascot necessary. Gronk was it.

The whole LA Bowl idea latching onto a celebrity — Kimmel, then Gronkowski — may have been ahead of its time, or past its prime, or just a nostalgic gesture. A fly-by-night title sponsor could still come into the picture and lose its business with poor accounting. But with Kimmel and Gronk, this idea of a reverse naming rights deal had some interesting merit.

“Since most bowl games have evolved into media and sponsor creations rather than always being based on athletic prowess, I’d expect to see more of this type of non-traditional alliance down the road,” David Carter, a USC sports business professor, told USA Today. “Bowl games are about branding and business development, whether linked to corporations or, in this case, individuals.

“Cross-promotional opportunities exist when high-profile celebrities attach their names to these bowls, even if the return on their time and energy is modest given the status of the game. Leveraging their legions of fans to at least consider the game – one lacking national appeal – is a win in and of itself and for both entities.”

The LA Bowl’s eventual “presenting sponsor” was first a non-descript bank. Next, Gronk’s angle was to have his family’s businesses, Gronk Fitness, and its sellable-product, its Ice Shaker, get some exposure.

In 2024, a new sponsor came aboard, something ironically related to promoting art and culture. By ’25, a different fitness-lifestyle product got greater billing. Through it all, the Gronk-host-with-the-most connection somehow remained. Like the guest who refused to leave the party even when the parents came home.

The fact we can’t recall any of these businesses, before or after the game, lends itself to some aspect of transparent accountable to their share-holders, which may be nothing more than a family living out of a storage unit with a really nice glue gun and power screwdriver. For what it’s worth, the LA Bowl was one of a few that have never formally announced to the public the payout totals for the teams involved in the game. That couldn’t be a solid business model.

Gronk, as a stand-alone party brand, had started to polish his event-added worth by aligning with the “GronkBeach” Super Bowl parties/music festivals going back to 2020 in Miami.

His social media following at the time became something of value for the LA Bowl organizers/advisors/dart-throwers-at-the-wall.

In October of 2023 when the torch was passed from Kimmel to Gronkowski, the later told the Los Angeles Times that part of his pitch to the game organizers was perhaps going up on the roof of SoFi Stadium to reenacted his famous “Gronk Spike” endzone celebration.

“It will probably be the highest Gronk spike of all time I’ve ever had in history,” he declared.

Lawyers, not keen on the liability issues, nixed it, but also opened up another obvious question: How does Gronkowski even get approved for a regular life insurance polity?

Gronkowski said having this particular bowl game named after him was sort of a full-circle moment. His last college game was with the University of Arizona — a 10-point win over BYU in the 2008 Las Vegas Bowl, played on the UNLV home field. The Las Vegas Bowl had been, prior to the LA Bowl, where the MWC champ faced a middle-of-the-pack Pac-12 tourist. That game disappeared during COVID 2020. After the LA Bowl seemed to pick up that contract, a new Las Vegas Bowl emerged to be played in the Las Vegas Raiders’ new home dome. That was seen as a replacement for what had been the California Bowl in Fresno, bringing tie-ins with the Big West, Mid-American Conference and … let’s not go down that gopher hole.

Give it up to Gronk, whose 11 seasons and two retirement ceremonies in the NFL included four Super Bowl wins, five times in the Pro Bowl and named to the NFL’s 100th Anniversary All-Time Team in 2019.

If Gronk had truly Karsashianed his way into this shallow end of the sports/business landscape, it was because all it took was someone to keep saying that it’s good to be Gronk, and enough believed it. Even him.

It was Gronk who, after the Patriots’ AFC Championship win in 2012, was asked how he would celebrate. He responded in Spanish: “¡Yo soy fiesta!” (“I am party!”). He then had the phrase trademarked.

It was also Gronk hired as a spokesman for Tide laundry detergent to promote a program so kids stopped swallowing Tide Pods as a form of entertainment. This apparently had to happen in our society. Our kids should now listen to Gronk to cure their craving for an unnecessary rinse cycle that involves a stomach pump.

The Tampa Zoo named its new-born one-horned rhinos “Gronk” in his honor. A thoroughbred horse named Gronkowski, after him because of its 6-foot-5 stature, would have run in the 2018 Kentucky Derby (it was scratched because of a fever) but it finished second in the ’18 Belmont Stakes at 24-to-1 odds. Gronk pitched an ice-shaking device on “Shark Tank” with his brothers. He was on Fox’s “The Masked Singer” and hosted WrestleMania 36.

A 2019 post on something called BellyUpSports noted: “The guy is simply one of the more pronounced personalities in the game, and the influence of personality definitely transcended the football field. I don’t know another athlete that has an entire episode of ‘Family Guy’ dedicated to him, a Wrestlemania appearance, a cereal, hot sauce and energy drink inspired after him, and those are only a few of the seemingly endless endorsements attributed to his name.”

There’s also his latest foray into Fox’s NFL pregame show in Century City, where Gronk chops it up live with Howie Long, Michael Strahan, Terry Bradshaw and whomever else is left around there.

Partying, it seems, also made Gronk a better player, as People magazine once documented it.

Perhaps Gronk’s greatest SoCal appearance was being on a toxic Netflix-sponsored celebrity roast for Brady in 2024, which took place at the Inglewood Forum right next door to SoFi Stadium. Roast host Nikki Glaser crafted the most quotable line from the night: “Tom lost $30 million in crypto. Tom, how did you fall for that? I mean, even Gronk was like, ‘Me know that not real money.’ Gronk actually does bit coin, where he just chews on a handful of nickles.”

In 2023, the then-Starco Brands LA Bowl Hosted by Gronk officially began when Gronk was among a group of folks called the New Directions Veterans Choir that sang a version of the National Anthem. The game also introduced a new official beverage: Gronk’s Cooler. It was a mix of bourbon, strawberry lemonade and topped off by vodka-infused whipped cream. Whatever fit into Gronk’s plant-based dietary needs.

A Sports Illustrated post sized it up this way: As documented in the 2003 holiday comedy Elf, the best way to spread Christmas cheer is singing loud for all to hear. No carols were in store, but Rob Gronknowski took Will Ferrell’s mantra literally on Saturday night in Los Angeles, helping to ring in Bowl Season by singing the national anthem …

If we’re reading this right, shouldn’t Will Ferrell be the real personality/host of this game?

For the Gronk debut game, UCLA became willing participants as it surprisingly finished above .500 with a 7-5 mark (including 4-5 in conference play, capped by a win over USC). It would be coach Chip Kelly’s farewell bash as he would leave to be the offensive coordinator at Ohio State, but none of that was known yet.

The one thing Kelly did, to call attention to the game as well as lay the groundwork to the future of the bowl system, was make headlines when he turned an otherwise mundane media scrum into a state-of-the-sport speech.

Riffing off a theme he had put out on a podcast in October of 2023, Kelly had a bigger audience now.

“I think we need to have a … commissioner,” Kelly started. “I think football should be separate from the other sports. Just because our school is leaving to go to the Big Ten in football … our softball team should be playing Arizona in softball. Our basketball team should be playing Arizona in basketball. … And they’ll say, well, how do you do that?

“Well, Notre Dame’s independent in football, and they’re in a conference in everything else. I think we should all be independent in football. You can have a 64-team conference that’s in the Power 5, and you can have a 64-team conference that’s in the Group of 5, and we separate, and we play each other.

“You can have the West Coast teams, and every year we play seven games against the West Coast teams and then we play the East — we play Syracuse, Boston College, Pitt, West Virginia, Virginia — and then the next year you play against the South while you still play your seven teams. You play a seven-game schedule, you play four against another conference opponent, division opponent, and you can always play against one Mountain West team every year so we can still keep those rivalries going. …

“But I think if you went together collectively, as a group, and said there’s 132 teams and we all share the same TV contract, so that the Mountain West doesn’t have one and the Sun Belt doesn’t have another and the SEC another, that we all go together, that’s a lot of games, and there’s a lot of people in the TV world that would go through it. … But I think if we still do the same and take all that money … that money now needs to be shared with the student-athletes, and there needs to be revenue sharing, and the players should get paid, and you get rid of [NIL], and the schools should be paying the players because the players are what the product is. And the fact that they don’t get paid is really the biggest travesty.

“Not that I’ve thought about it.”

The Kelly speech is included in a new Bill Connelly book, “Forward Progress: The Definitive Guide to the Future of College Football.”

It resonated even more when, in early December 2025, after the 16-team CFB playoff was announced and No. 11 Notre Dame and No. 12 BYU were left out, the Irish team went against ESPN’s wishes and balked at going to the Pop-Tarts Bowl in Orlando, Fla., against the Cougars in what amounted to the Warmed Oven Toaster Treat Bowl. That set off more discussion about just how tenuous this whole non-CFB bowl structure had become, with a future that seems doomed at best.

As Stewart Mandel wrote for The Athletic:

“Bowl games have been around for 123 years, and they’ve remained pretty darn resilient despite their decreasing relevance over the past dozen years. … (But this year) more than a half-dozen of those teams, from Florida State to Rutgers, said ‘no thanks’ to the last available bid in the ESPN-owned Birmingham Bowl. Finally, nearly 10 hours after the CFP field was first revealed Sunday, organizers announced the game would pit Sun Belt rivals Georgia Southern and Appalachian State, which faced each other Nov. 6. All in all, not a fun year to be one of the guys in those ugly blazers.”

What is the official LA Bowl blazer, by the way? Gronk’s No. 87 jersey?

In 2023, UCLA’s 35-22 win over Boise State, 35-22, came before an announced crowd of 32,780 papering the 70,000-plus seat SoFi Stadium. Which made it all the more confusing when UCLA administrators started using SoFi Stadium as leverage for a new home field, wanting to get out of its current non-rent deal with the Rose Bowl, and everyone has an opinion about that.

Now things really really getting curiouser and curiouser.

Ponder that as we wait for Gronk to emerge from a cloud of Hollywood-made fog to emerge with the giant WWE title belt that he will hand off to the LA Bowl game MVP.

The college football legacy in Los Angeles’ history can be looked at this way: If we accept the premise that the LA Bowl personifies the “sunny” and “funny” side of sunny Southern California, and it never meant to challenge the prestige of Pasadena’s Rose Bowl, what’s the harm?

The Rose Bowl set the standard. The LA Bowl is one step from stepping off the bottom rung. But it had a lot of history to reflect on when shaping its purpose.

Go back to 1924 and the Los Angeles Christmas Festival, aka Christmas Festival Bowl

Pasadena’s Rose Bowl first happened in 1902, took a 14-year break, then came back in 1916 for a run that has endured two World Wars and a COVID pandemic even if it has meant temporarily relocating.

After USC finally made it to its first Rowl Bowl in 1923 — the year it was first played in the current Rose Bowl — and posted a 14-3 win on Penn State, it wanted more. The next season, USC tied Stanford for the Pacific Coast Conference title, yet the Rose Bowl folks picked Stanford, as new blood, to face Notre Dame for the Jan. 1, ’25 matchup. To placate USC, a group formed this Christmas Festival/Bowl. Even though Missouri’s Tigers had not practiced in two weeks, the team still made the trip.

In that ’24 season, there were only three total bowl games — the third was the Dixie Classic in Dallas as West Virginia Westleyan outlasted SMU.

Then the Christmas Festival disappeared. But not the idea.

In 2010, there was the attempt to launch something called The Christmas Bowl back at the Coliseum. It came up again in 2011 and 2014. A group led by someone named Derek Dearwater tried to get this one certified as a way to pit the then-Pac-10’s No. 7 team against the runner-up in the Western Athletic Conference. Again, if you’re seventh in a 10-team conference, there’s a decent chance you won’t have a .500 or better record and meet the minimum requirement. Yet, by 2014, the pitch was to have the Pac-12’s No. 8 team against the Mountain West’s No. 7 team.

Really, how much lower could you go?

The game, if not played on the actual Christmas Day, had a Dec. 21-to-24 window at the start, and that expanded to Dec. 27. The benefactor was to be the Children’s Miracle Network. Miraculously, it was turned down, even as the organizers tried to pitch this as some kind of legacy event, following a tradition that was never really a tradition but a one-off fluke.

During all that discussion, we exchanged emails with Dearwater after he took offense to our “derogatory” tone about the chance of this event. Fact is, the general public didn’t even realize this was in the works to be foisted upon them.

We saw it as a public service announcement. And a warning.

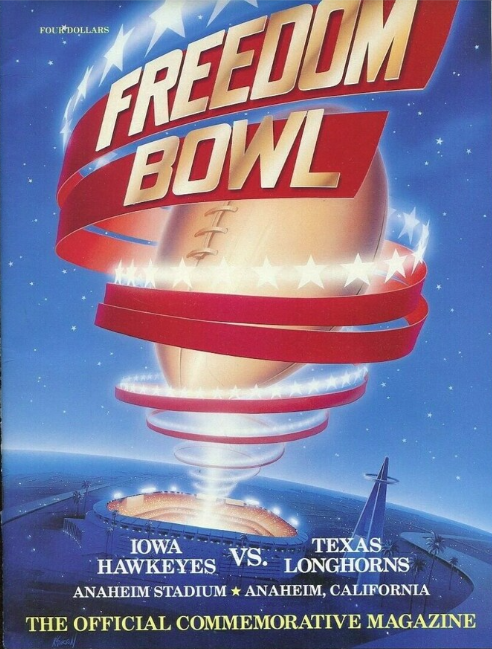

The longest-running, non-Rose Bowl game in SoCal turned out to be Anaheim’s 11-year-run of the Freedom Bowl before it was cut free of its moorings.

From 1984 to ’94, Anaheim Stadium was the home site for a bowl game that took a Western Athletic Conference team against a decently-ranked, left-by-the-wayside opponent.

In its first game, Iowa’s Chuck Long set a then-bowl-game record with six touchdown passes in a 55-17 win over No. 19 Texas. Attendance was 24,093 on a very rainy night. The group that televised the game, Metrosports, also went bankrupt and was unable to pay its TV rights fees of $340,000 to the Freedom Bowl, which had to secure bank loans to pay Iowa and Texas.

The Freedom Bowl was also the spot where in 1992, No. 23 USC absorbed a painful 24-7 loss against Trent Dilfer and Fresno State. It led to the end of Trojan head coach Larry Smith’s tenure (adding to the fact USC lost its last three in a row, following stumbles against UCLA, Notre Dame and then the Bulldogs). The next season, USC brought back John Robinson and he was there to see a 28-21 win over Utah.

Redemption? Eh.

The Freedom Bowl ceased to happen the same year the NFL’s Rams moved out of Anaheim Stadium and headed off to St. Louis.

What else do we have?

== In 1967, the Junior Rose Bowl in Pasadena became an official bowl game, a month before the “real” Rose Bowl on Jan. 1, ’68, and was one of the 10 bowl games that season. It saw Cal State Northridge lose to West Texas State 35-13. The Junior Rose Bowl had four more occurrences, including Long Beach State posting a 24-24 draw against Louisville in 1970.

== When San Diego’s Holiday Bowl sprung up in 1978, there were 15 post-season games. When BYU clinched the 1984 national title in the Holiday Bowl over Michigan, that gave it some clout among the 18 bowls around at the time, including the first Freedom Bowl in Anaheim.

== One other historic bowl of note that happened in Los Angeles, and it has a plaque to remember it on the Coliseum’s Memorial Court of Honor.

The Nov. 23, 1961 Mercy Bowl, a Thanksgiving Day game between Bowling Green and Fresno State, happened to raise funds for the Cal Poly Memorial Fund, assisting those affected by the 1960 plane crash that took the lives of 16 players and 22 total from the Cal Poly San Luis Obispo football team as it was returning from a game at Bowling Green in Ohio. Among the survivors was SLO quarterback and future USC head football coach Ted Tollner.

The Southern Pacific scheduled a special train to carry San Luis Obispo residents to the game. Roy Easley, captain of the Cal State L.A. team, sent letters to captains of most of the country’s college teams, urging them to buy a symbolic 11 tickets. The one-time event attracted a crowd of 33,145 and disbursed $278,000.

In 1971, there was Mercy Bowl II, with Cal State Fullerton beating Fresno State 17-14 in Anaheim to help benefit the children of three Cal State Fullerton assistant coaches and a pilot killed in a plane crash a month earlier.

There hasn’t been any sort of bowl game like it in Southern California since. Maybe this charity game business model is out of touch with today’s ticket buyers.

When the 2025 college football season started before Labor Day weekend, Will Leitch wrote a piece for The Athletic titled: “College football is still worth cherishing, despite all the junk surrounding it.”

His disappointment was that “the person college football is catering to right now, their ideal customer, is not the lifelong fan who has had the same tailgate spot for decades, or obsesses over their ideal quad box for their Saturday television viewing: It’s basically a guy who is only half paying attention, in, like, New Jersey, or Arizona maybe, halfheartedly glancing at his phone, maybe thinking about making a bet, a guy who doesn’t particularly care that much about college football but does recognize the name “Michigan” or “Georgia” or “Notre Dame” and thinks, “OK, maybe I’ll watch that game. That’s A Big Game.” … This can lead to despair, the helplessness that comes when you realize the thing you care so deeply about does not care about you anymore.”

The LA Bowl works in that ecosystem now, even if sports gambling is not legal in California. How convenient. Still, it provides action.

Leitch is also fascinated by how we use college football to get some nasty pleasure of watching a coach be in the hot seat. “Being fired is something that you would never wish on anyone,” he wrote. “Unless, of course, they are a college football coach. Then we love it. … We even like to imagine sadistically entertaining scenarios in which the coach might get the axe.”

The LA Bowl could have been a place where a coach got fired after a loss. Or chased in their chips elsewhere like Chip Kelly.

Michael Weinreb wrote on his “Throwbacks” Substack platform: “College Football Makes No Sense. But what Does Right Now?”

“If you follow the online dialogue about college football, after a while you begin to realize that it’s all become one very weird inside joke. If the NBA’s online presence is a running gossip column, and the NFL’s online presence is defined by the balance between random all-caps screaming about fantasy football kickers and genial Barnwellian nerddom, college football’s online presence is essentially an Insane Clown Posse concert. The Juggalos in this trickster evolution recognized that embracing the sport’s inherent weirdness was the best way to convey the emotion of a sport that was lucrative, exploitative, and often seemed to make up the rules as it went along. …

“At some point, Pop-Tarts began sponsoring a bowl game, and then they began to recognize that weirdness and randomness was part of college football’s brand, and Pop-Tarts—itself a nostalgic and nonsensical product—have effectively co-opted that weirdness and transformed it into an act of performative cannibalism. …. It makes no sense, but it doesn’t have to make sense, because college football makes no sense.”

Especially, as Weinreb points out, when the University of Auburn decided all of the sudden to claim ownership of seven national championships that it was apparently too modest to boast about. Until now. As boasting has been normalized.

“We have come to embrace the forced consumption of ultra-processed mascots,” Weinreb concludes. “We don’t do things the way other countries do, and sometimes that means we have to suffer through our own idiocy in order to get to a better place.”

In the end, those who ran the Hollywood Bowl iconic concert venue were hopeful no one confused it with this LA Bowl thing. The LA Bowl’s Wikipedia page tried to help when it included: “Not to be confused with the Hollywood Bowl.” The Los Angeles Philharmonic Association and Los Feliz Neighborhood Watch captains thanks you and ask you to not park on a neighbor’s lawn.

Also to note: The “Gronk Push” for an athletic event may also seem to be running out of juice.

A New York Times magazine story in early 2026 on the creation of two new women’s professional volleyball leagues trying to capture the WNBA model mentioned how the Pro Volleyball Federation was trying to market its first All-Star game in February of ’25, set for CBS coverage.

“How could P.V.F. get viewers to stick around?” the story started. “Not just to the end of the match, but with the sport.

“Landing a random sports celebrity seemed to be P.V.F.’s strategy to hook potential fans. The league had made an offer to the former National Football League player Rob Gronkowski to host the match. He had a big following and stage presence, but it was like asking Simone Biles to host a men’s lacrosse tournament.

“On a video call to discuss the plans, Leonard Armato, a longtime sports marketing executive and a consultant for P.V.F., urged the board of directors to try something else. ‘Nobody’s going to tune in to watch Gronk, you know, jump around,’ he said. ‘They’re going to tune in because it’s the Pro Volleyball Federation All-Star match, the first ever women’s professional all-star match.’

“They should consider other options, he argued. … Gronk didn’t work out, but the league ended up hiring different celebrity hosts with no obvious connection to volleyball, either … The 8,000-person venue in Indianapolis was nearly full, and more than 400,000 people watched at home.

“The broadcast, in other words, was a success. But would the league be one?”

Perhaps, no thanks to Gronk.

In 2024, a few new bowl games were added to December, including the The Snoop Dogg Arizona Bowl Presented by Gin & Juice By Dre and Snoop.

This just seems as odd as the LA Bowl Hosted by Gronk.

Why wasn’t Gronk back in Tuscon hosting that toxic mess, which would have allowed Snoop Dogg to come back to rule on his SoCal home turf with a smoke-filled entrance?

Perhaps we’ll never have to figure that out once all these ancillary CFP distractions are spiked from the master schedule.

Who else wore No. 87 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

Danny Farmer, UCLA football receiver (1995 to 1999):

If Rob Gronkowski was known a signature spike after caching a TD pass, Danny Farmer’s signature spike came on the volleyball court as he played that sport at the same time he was becoming the football team’s all-time leading receiver. In a 1999 Sports Illustrated feature, Farmer tried to explain how after college recruiters thought he was too slow for football and too short for volleyball, despite what he proved at Loyola High in L.A. He couldn’t get any college to let him play both sports. UCLA eventually did. His entrance into the UCLA Athletics Hall of Fame in 2015 was based as much on the fact he had more than 3,000 yards receiving as well as his outstanding volleyball career. A walk-on who became the first freshman to lead the team in receptions with 31, Farmer ended up with the Red Sanders Award as the team’s Offensive MVP as a senior and got an NCAA post-graduate scholarship, then put in five years in the NFL. On the volleyball team, Farmer (wearing No. 15) helped the Bruins to the 1996 and ’98 NCAA titles, becoming an All-American player in 1999. His father, George Farmer, was a 2000 inductee into the UCLA Athletics Hall of Fame as a three-year football receiver (wearing No. 85), one year of basketball and one year of track. George Farmer was also a three-sport star at La Puente High wearing No. 80 and put in five years in the NFL.

Ralph Heywood, USC football left end (1941 to 1943):

The All-American out of Huntington Park High was captain of the ’43 Trojans team that went 8-2 and shut out Washington in the Rose Bowl. Heywood led USC in receiving in ’42 and ’43 and had the school’s first 100-yard receiving game (four catches, 101 yards vs. St. Mary’s Pre-Flight) in ’43. He also led USC in punting in ’41 and ’42. His 32-year-career in the Marine Corps saw him serve in World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War. He played in just five games in the ’43 season for USC before he was drafted by the Marines and went to the South Pacific.

Billy Truax, Los Angeles Rams tight end (1964 to 1970): A converted outside linebacker and defensive end, Truax was second on the team with 37 receptions in 1967 and third with 487 yards. His trade with Wendell Tucker to Dallas in 1970 brought Lance Rentzel to the Rams.

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 87: The (fill-in-the-blank) LA Bowl, hosted by Gronk”