This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 38:

= Eric Gagne, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Clyde Wright, Los Angeles Angels

= Burr Baldwin, UCLA football

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 38:

= Dave Goltz, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Todd Worrell, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Roger Craig, Los Angeles Dodgers

The most interesting story for No. 38:

Leon Burns, Long Beach State football running back (1969 to 1970)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Long Beach, South Los Angeles

Long Beach State retired its football program in 1991. Not long before that, the school retired the one and only jersey number from its 37-year run. That was the No. 38 that Leon Burns wore for just two seasons.

“To 49er fans, Burns was Superman,” it reads on that bio that the school posted to honor the 6-foot-2 bruiser, 225-pound tailback. “He could bench press 450 pounds and run the 40 in 4.5 seconds. He could also play football, earning first team, collegiate division All-America recognition … (and the) only player ever to represent LBSU in the now defunct College All-Star game.”

The Superman reference was specific to one of the 49ers’ biggest program wins ever — a 27-11 victory over San Diego State in 1970 to clinch the conference title before some 39,000 at Anaheim Stadium.

After the game, Burns took off his jersey and showed everyone he had a Superman T-shirt on underneath.

“I guess it was my idea,” he admitted to the Long Beach Press Independent Telegram afterward. “Somebody put an article in the paper: ‘Does he really have an ‘S’ underneath?'”

Burns would set the NCAA Division-II record for carries in a game (35) and for all-purpose plays (360) in a season. Having once rushed for 300 yards in a single game, he also set school records for career carries (655), rushing yards (2,809), points (304) and touchdowns (50).

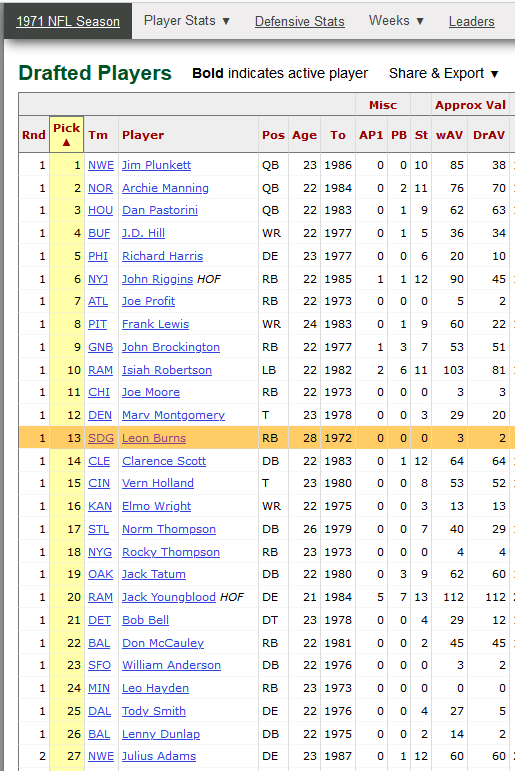

When the San Diego Chargers did their due diligence and made Burns the 13th overall pick of the 1971 NFL Draft, and the fifth running back, one glaring fact stood out — Burns was 28 years old. By two years, older than any other draftee.

The gap in Burns’ resume between high school and college — a four-year prison sentence in Oakland he started serving as a 19-year-old. Missing from today’s “Whatever happened do?” search for Burns — he was shot to death in an unsolved murder in South Los Angeles just before Christmas 1984 and died at the age of 42.

It happened two years before he could see his school retire his number.

The background

The seventh of eight children in a strict Catholic family growing up in Oakland — his mother died when he was 14 and he went to live with an older sister as his father was gone often as a chef for the Southern Pacific railroad — Burns graduated from all-boys St. Mary’s High and worked in a variety of jobs.

He explained in an interview with Rich Roberts of the Long Beach Independent Press Telegram that before his 19th birthday, he was working in Seattle at the World’s Fair and two men apparently involved in a pawn-shop robbery — he knew one of them — were escaping from collecting what they believed were fenced stolen goods. Burns drove them to San Jose. When he returned to Seattle, he was arrested. In a confusion of information and other cases — he was taken in even through witnesses described him as 5-foot-6 and 130 pounds — Burns was convicted after two hung juries of an “accessory before and after the fact wherein a felony was committee.”

“I’ve always felt that if I had money I never would have gone (to conviction),” he said.

He drew a five-years-to-life prison term for which he served four years in San Quentin, Folsom, Soledad and other places.

Inside the prison gates, Burns loved to lift weights and read legal books, filing writs and appeals on his behalf. He also helped other inmates with legal research. Burns consistently maintained his innocence. He worked jobs in the textile mill making two cents an hour. He shoveled human manuer in the sewage plant for four cents an hour. He fought forest fires — eight hours unpaid, and 30 cents an hour after that.

The two sports he could at least do boxing and weightlifting. In 1965, Laney College coach Don Kloppenberg brought his team to the facility for a game against the inmates. Burns was playing football. Kloppenberg was impressed.

After his release, Kloppenberg recruited Burns to play for him at the Oakland community college. Bench pressing 500 pounds and racking up 700 yards on a 6.3 average as a freshman wearing No. 38, Burns received more than 100 college recruit letters after his two years at Laney were up.

Somehow Burns gravitated to Long Beach State to play for coach Jim Stangeland, a successful Long Beach City College head coach and USC assistant who was on a staff leading teams to three Rose Bowls and the 1967 national title.

Stangeland attracted dozens of new transfers at Long Beach State, strange into itself. It would come out later how that happened.

Before the ’69 season, Long Beach sports fans were told by scouts that Burns was nicknamed “The Thing” because he was so devastating a runner. “His straight arm is so powerful it could break a man’s neck,” said 49ers offensive coach Chuck Boyle. “When I called for 10 pushups during a practice, he asked to 50. I’d swear he did those 10 pushups in three seconds or less.”

To start the 1969 season, Burns started three games at fullback and was shifted to tailback.

“Leon was a human wrecking ball,” teammate and fullback Dave Brown said of him. “But we couldn’t figure out why he was at fullback. He had never blocked anyone in his life. At first Leon didn’t know the plays at tailback, and we’d just tell him, ‘run to the left or run to the right’.”

In his first game at his new position, Burns carried the ball 26 times for 185 yards and four touchdowns on a muddy field in Honolulu as the 49ers defeated Hawaii, 28-14.

“By then,” Brown explained, “Leon knew the plays, which were, basically, ‘run wherever the hell you want.’ ”

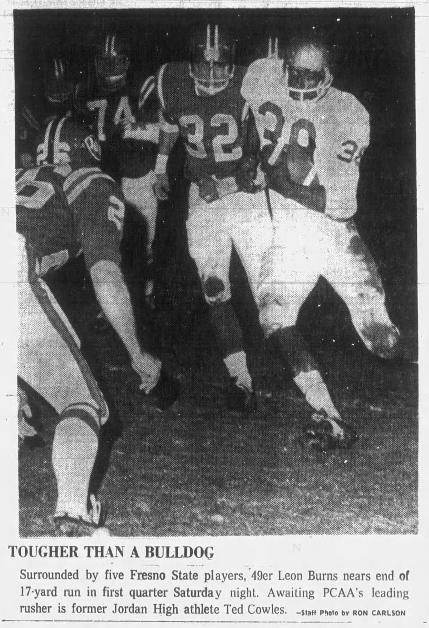

After Burns compiled 1,036 yards and 14 touchdowns after seven games going into a Nov. 8 game against Fresno State at Veterans Stadium, Stangeland was asked to compare him to what he saw of O.J. Simpson during his days coaching at USC just two years earlier.

“There are a lot of experts who would say people who compare anyone to O.J. Simpson are crazy, but I’ll tell you the truth, I’d hate to have to stake my life on who pro scouts said was better — O.J. or Leon,” said Stangeland. “You can’t really say Leon is another O.J. Leon isn’t nearly as fast as O.J. but he is much stronger. Although he goes about it in a different way, he is as effective as Simpson.”

Some newspaper headlines were keen on pointing out that Long Beach State’s roster was led by an “ex-con.”

“What they’re doing to me in the papers without knowing the background is the same as what happened to me before,” Burns would say. “I had nothing to dow ith it and I was condemned without going through the facts.

“People are more ready to condemn than to praise, but it’s made me a stronger person. Hardship is easier to accept once you’ve been through it.”

Burns would have the best statistical season in the nation with 1,659 yards rushing and 26 touchdowns (plus one more TD when he caught 10 passes for 149 yards), and was involved in 360 plays from scrimmages. He scored 162 of the team’s 264 points. The 49ers were second in the Pacific Coast Athletic Conference with an 8-3 record.

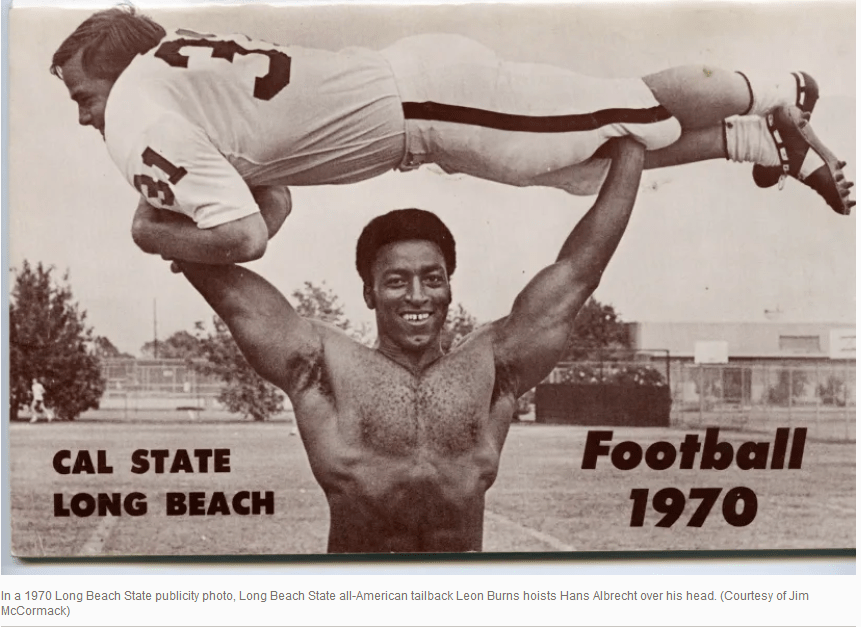

Before the 1970 season, Long Beach State’s marketing department came up with a unique promotional campaign — a bare-chested Burns lifted teammate Hans Albrect, all 5-foot-9 and 210 pounds, over his head like a barbell. It came with a bumper sticker asking: “Have You Seen LEON?”

To start his final season, Burns fought through early ankle injuries and the 49ers lost two of their first two games. Four weeks later, on Halloween night, Burns pulled together then 300-yard rushing game on 28 carries in a 49-20 win over Cal Poly San Luis Obispo. It included TD runs of 80 and 85 yards. He scored on another 1-yard run and a 16-yard reception from quarterback Randy Drake.

The next week, in a 50-14 win over Fresno State, Burns ran for five touchdowns.

Long Beach State’s win over SDSU in late November at Anaheim Stadium before more than 37,000 came as a result of the 49ers using Burns was used as a decoy. He ran 18 times for 63 yards nursing a tender ankle, but it allowed fullback Hans Albrecht to run 13 times for 123 yards and score on a 59-yard run in a 27-11 upset against an Aztecs team that had lost once in its previous 32 games with coach Don Coryell.

In the end, Burns piled up 1,033 yards on 275 carries with 19 touchdowns — all again best in the nation — adding one more receiving TD with five catches for 89 yards. His 120 points were half the team’s 240 total and the 49ers finished 9-2-1, 5-1 in the PCAA.

Advancing to the 1970 Pasadena Bowl, also known as the Junior Rose Bowl, Burns ran for all three of his team’s touchdowns and survived in a 24-24 tie with Louisville, coached by Lee Corso, before just 20,000 enduring the rain. It was the only bowl game in the school’s history.

Burns’ two years at Long Beach State were enough to set marks for career carries, yards, touchdowns and points scored. He was recognized by the Pro Football Weekly’s College Football All-American team.

In the Jan. 2, 1971 East-West Shrine Game at the Oakland Coliseum in his hometown, Burns, a replacement in the West backfield just days earlier, was his team’s top rusher with 88 yards on 22 carries.

Burns said he purposefully got a degree in political science and had a desire to become a lawyer, which developed while filing appeals of his robbery conviction. He married his wife, Diahan, in 1968 and they had three children prior to the arrival of the NFL draft on Jan. 28, 1971.

That quarterback-heavy draft saw Jim Plunkett, Archie Manning and Dan Pastorini taken as the first three choices. Ken Anderson, Lynn Dickey and Joe Theismann would come later. Future Hall of Famer John Riggins was the first running back taken at No. 6 by the New York Jets. Three more running backs were taken after him.

Then the Chargers decided on Burns.

Burns was already hailed by some as “the next Jim Brown.”

Future Hall of Famers like Jack Youngblood (Rams, 20th overall), Jack Ham (Steelers, 34th overall), Dan Dierdorf (Cardinals, 43rd overall) and Harold Carmichael (Eagles, 161st overall) would come to those who waited.

The Chargers were coming off a 5-6-3 record. Mike Garrett, then 26, was a backup running back on the team. It had little offensive juice behind quarterback John Hadl.

Harland Svare, the former Los Angeles Rams coach, was the team’s GM who would end up coaching the last five games after Sid Gillman sputtered out of the gate. Burns was Svare’s pick.

Reports were that in July of 1971, Burns signed a five-year deal worth some $200,000.

“I’ve had my eye on Leon since the day I met him,” said Chargers coach Sid Gillman. “Hell, Leon was ready to play in this league then. We’re not worried about Leon’s age. We didn’t draft him for what he could do 10 years from now, but for what he could do for us right now. Leon is a fundamentally sound athlete because of the coaching he has received.”

Burns said: “I don’t really look at this is a step up. Everyone who plays football is just like me — a human being, and human beings are all made the same. They all feel pain.”

In ’71, Burns started four of the Chargers’ 14 games, had 61 carries for 223 yards and a touchdown. And that was it. He was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals a day before the 1972 draft for running back Cid Edwards. With the Cardinals, Burns had 26 carries for 69 yards and two touchdowns. And his NFL career was done at age 30.

After a year out of the game with ankle injuries, Burns signed with the new World Football League’s Portland Storm in 1974 and posted 193 yards rushing on 51 career. That would be it for his professional playing days.

But his name would remain in the news.

The legacy

In the fall of 1972, the NCAA started an investigation into the Long Beach State’s football and basketball programs — the later, under coach Jerry Tarkanian — in what was called Case No. 427, revealing a systematic policy of improprieties and violations that Sports Illustrated investigated in a 1974 series as something systemic in the entire college sports universe.

Of the 74 violations charges, 23 were for the football team, and 12 of them focused on Burns.

According to SI, Burns was charged with accepting $275 a month to assist in the payment of rent, he and his wife were given cash for “various purposes,” an assistant coach offered him “improper inducements, including a job for his wife and additional financial aid for housing,” and his “household goods were stored for approximately one month in a storage area owned by Strangeland.” The assistant coach was also accused of helping Burns “in moving his furniture free of charge; and that his car was repaired free by a booster.”

Burns, with former Long Beach State teammate Terry Metcalf a member of the St. Louis Cardinals at that point, was quoted: “I feel that I was exploited and cheated out of a lot of money. I’m writing a book on the subject.”

Diahan Burns, who had separated from Leon Burns in December of 1973, told SI that Long Beach State “didn’t recruit Leon. They recruited me.” She said when “they brought me down for a weekend, I told (assistant coach Bill) Miller that I was making $500 a month in Oakland and that they’d have to get me a job in Long Beach for at least that much. He said no problem. He also agreed to take care of our moving expenses and getting us a house. So I said OK, but just put it all down in writing, and he did.”

She also said the team got her and Leon a two-bedroom house in Lakewood that came with an apartment that could rent to Burns’ Long Beach State teammate, receiver Curtis Biggers.

“If I needed money for groceries or anything I went to Miller. He never turned me down because with that signed paper I had a hold on him. I never felt like I was asking for too much. They were killing Leon, making him carry the ball 40 times a game. They took more from us than they gave.”

Miller did admit getting Diahan Burns a job at nearby McDonnell Douglas for $580 a month.

“All coaches do things like that,” he said.

Long Beach State’s football program that launched in 1955, six years after the school opened in 1949 (hence, the ‘49ers). It was trying to draw on fans of USC and UCLA living in the area, happened at a time when private schools like Loyola and Pepperdine were shutting down their programs. The 49ers could only attract a few thousand fans first at Long Beach Wilson High and then at Veterans Memorial Stadium in Long Beach that drew bigger attendance for high school games.

In 1982, the program led the nation in total offense at 326.8 yards a game. In 1986, running back Mark Templeton set the NCAA record for most receptions by a tailback in a single game (18) as well as in a season (99). That year, the program almost saw an ending until some $300,000-plus was raised by boosters to keep it afloat.

But it was all done by 1991 as a member of the Big West Conference. It had recruited Angel Stadium from 1977 to 1982 to be its home field as the Los Angeles Rams were also there. Officially, it had a 23-year run as a major college program affiliated with a conference starting with Strangeland’s 8-3 season in 1969. The program’s all time record: 199 wins, 183 losses, and four ties.

In ’91, then-president Curtis McCray disbanded the program because of financial shortfalls resulting from a tightening state budget, a decline in fan support and rising operations costs.

It had been given somewhat of a reprieve in 1990 when former Los Angeles Rams coach George Allen agreed to take over the program, but he only lasted one year and died not long after that season ended. When the program finished, a tailback named Terrell Davis was on the roster. He transferred to Georgia and became a future Pro Football Hall of Famer with the Denver Broncos.

More than two dozen of the 1,300 Long Beach State football players made it into the NFL. Linebacker Dan Bunz was the only one aside from Burns to be a first-round NFL pick out of the school (No. 24 overall by San Francisco in 1978, where he was a two-time Super Bowl champion).

But memories of Burns were burned into the psyche of those who saw him in the 49ers jersey.

“We heard all about Leon,” said 49ers safety Jeff Severson. “He was everything they said he was.”

“He played like a man compared to the boys he was playing against,” said Dan Olsen, who graduated with his master’s degree in 1984, and is the technology coordinator of the journalism and public relations department.

When he was out of football, Burns gave up on a law career.

Burns name came up again on Dec. 22, 1984.

A brief story posted on the news wire services noted that Burns, who had been living in Torrance, had been found dead by two female companions in the rear of a South L.A. apartment complex shot dead in the chest. Police speculated robbery as a motive. The Long Beach Press Telegram reported Burns and the other two allegedly went into the complex to purchase cocaine at an apartment that had been converted into a “rock house,” a heavily fortified location where a pure form of cocaine is sold.

“He was quite an idol to the youngsters,” Long Beach State athletic director Fred Miller, in Burns’ obituary that ran in the Oakland Tribune. “Even to kids who knew about his (prison) background. He was a great influence to the rest of the team.”

History lesson

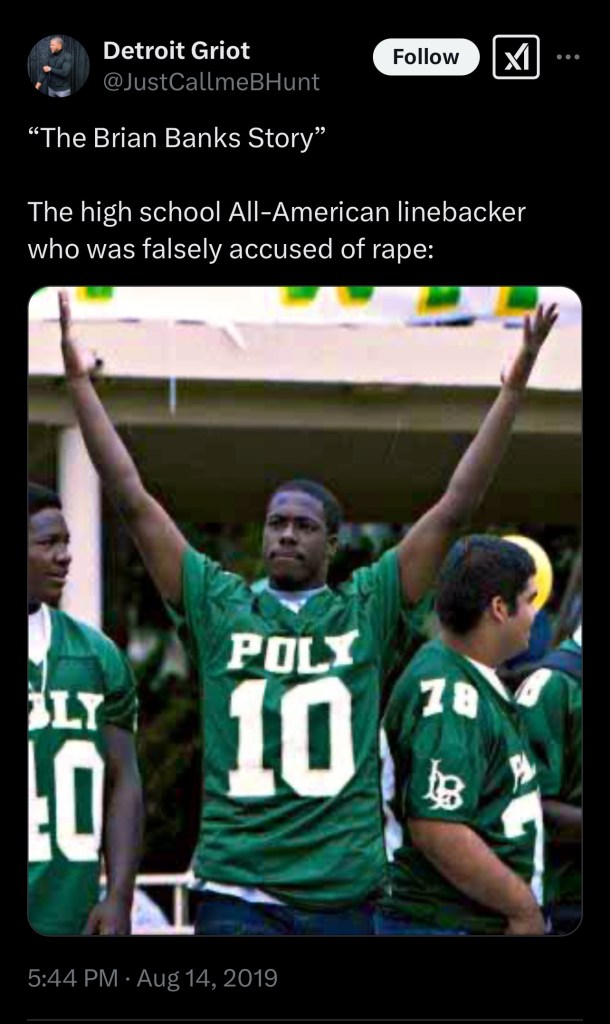

Leon Burns never had a Hollywood version of his prison-to-football story.

But Brian Banks did.

The 2018 film, “Brian Banks,” told the story of the linebacker from Long Beach Poly High who, as a junior in 2002, made a verbal commitment to play at USC. A female classmate accused Banks, then 16, of a rape. The 6-foot-4, 225-pound senior was taken into custody and faced a possible 41 years to life sentence. Banks’ lawyers bargained for five years in prison, five years of probation and register as a sex offender — leaving Banks to have just five minutes to accept it or go to trial. Banks had assumed that if he pleaded no contest, he would get probation and no jail. It all led to Banks spending six years in jail and five years on parole. The girl who accused him also was part of a lawsuit against the school claiming the campus was unsafe, and she and her mother won a $1.5 million settlement.

Banks’ conviction, however, was overturned in 2012 after his accuser confessed to making up the story. The California Innocence Project came to Banks’ aid. In 2013, the school won a $2.6 million judgment against the girl.

The film was adapted from a book on Banks’ story, “What Set Me Free,” published in 2019.

In the aftermath, Banks was offered a tryout with the NFL’s Seattle Seahawks, where former USC coach Pete Carroll was now in charge in 2012. San Diego, Kansas City and San Diego also tried Banks out. Banks hooked on with the United Football League’s Las Vegas team in the fall of 2012 and appeared in two games — 11 years after his high school career ended.Banks ended up in the NFL with Atlanta in 2013 and played four pre-season games with the Falcons before he was released in late summer. In 2014, NFL commissioner Roger Goodell asked Banks to speak at the NFL Draft Symposium and he was eventually hired by the league in its department of operations.

Who else wore No. 38 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

Eric Gagne, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1999 to 2006):

Best known: The 2003 NL Cy Young Award winner and sixth in NL MVP voting was 55-for-55 in saves that season, striking out 137 of the 306 batters he faced in 77 games over 82 1/3 innings. During a run of three-straight NL All Star appearances from ’02 to ’04, Gagne was fourth in Cy voting in ’02 and seventh in ’04 as he piled up season save totals of 52, 55 and 45. Amidst that streak of becoming the fastest reliever to ever get 100 saves, Gagne set an MLB record with 84 straight saves in 84 chances. That combined eight to end ’02, those 55 in ’03, and the first 21 of ‘04. The whole streak covered just 89 innings — but it included 139 strike outs, just 44 hits and only eight runs allowed. Before that three-year run, Gagne had no saves for the team. After that, he had just nine over the next two seasons as injuries derailed him in 2005 and ’06. Gagne signed as a free agent with Texas before the 2007 season. After going to Boston and Milwaukee, he signed as a free agent back with the Dodgers before the 2010 season and was released during spring training. Gagne was listed in the 2006 Mitchell Report as someone who illegally used steroids or other performance enhancing substances during his career. He admitted to HGH in a 2010 interview with the Los Angeles Times while he was attempting a comeback in the Dodgers’ minor league system. Two years later, his book “Game Over: The Story of Eric Gagne,” alleged 80 percent of his Dodgers teammates were using performance-enhancing drugs while he was with the team. “I was intimately aware of the clubhouse in which I lived,” Gagne says in the book. He did not name names. Welcome to the Jungle. Game over.

Not well remembered: The Montreal native wore No. 48 after he came off Tommy John surgery and had mad 24 starts. He made another 24 starts in ’01 after switching to No. 38 and was converted to a closer.

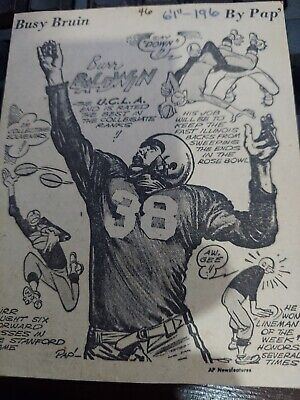

Burr Baldwin, UCLA football end (1940-42, 1946), Los Angeles Dons (1947 to 1949):

Best known: Seventh in the 1946 Heisman voting, after he served two years in World War II, Baldwin was the first to earn All-American honors at UCLA and have his No. 38 retired. He scored a touchdown in UCLA’s first-ever win over rival USC, 14-7, in 1942. A 1986 honoree in the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame.

Not well known: The Bakersfield High star joined the All-American Football League’s Los Angeles Dons and played three seasons as a two-way end, catching 24 passes, wearing No. 52.

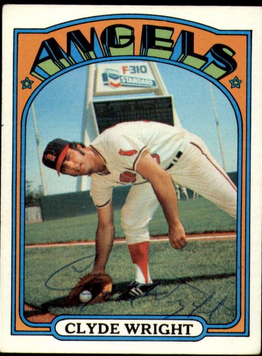

Clyde Wright, Los Angeles Angels pitcher (1966 to 1973):

Best known: The Angels’ ace in 1970, Wright had a 22-12 mark and 2.83 ERA in 39 starts, earning an AL All Star appearance — and tagged with the loss as he was on the mound, giving up a hit that allowed Pete Rose to barrel over Ray Fosse with the winning run in the 12th inning. The AL Comeback Player of the Year and sixth in the Cy Young voting that season, Wright threw a no-hitter against Oakland Athletics on July 3, the first of its kind at the new Anaheim Stadium. Wright’s 22-win season remains a franchise record, tied by Nolan Ryan in 1974. Wright’s son, Jared Wright, was the Orange County High School Football Player of the Year at Katella High in Anaheim and pitched in the major leagues from 1997 to 2007.

Not well known: Wright was a spot starter for his first four seasons and after posting an 1-8 record in 1969, the left-hander wasy wavied by the Angels. Teammate Jim Fregosi convinced him to play winter ball with him and that led to Wright experimenting with a changeup and screwball, giving a reason for the Angels to bring him back.

Have you heard this story:

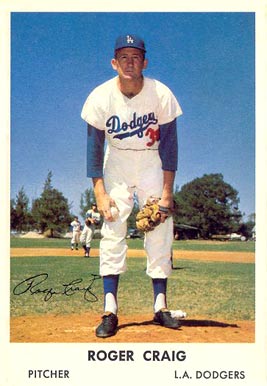

Roger Craig, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1959 to 1961):

Switching from No. 40 to No. 38 after the team’s first season in Los Angeles, Craig, having already made a mark with the Brooklyn phase of the franchise, led the NL with four shutouts during the team’s World Series run, posting an 11-5 record and 2.06 ERA going from starter to reliever as needed. Picked up by the New York Mets in the expansion draft — and leading the league with 24 and 22 losses in ’62 and ’63 — Craig’s biggest impact of the game was as a pitching coach and manager, teaching many star pupils the split-finger fastball. Craig started his post-career as a Dodgers scout and managed their Triple-A Albuquerque team before former Dodgers GM Buzzie Bavasi hired him as the first pitching coach for the expansion San Diego Padres in 1969. He was elevated to manager in 1978 and lasted through ’79, jumping to the Detroit Tigers and shaping their pitching staff. He managed the San Francisco Giants (1985 to ’92) and developed the mantra “Humm Baby,” winning 586 games as a skipper there.

Dave Goltz, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1980 to 1982):

At the height of the free-agent frenzy that opened the decade of the 1980s, Dodgers general manager Al Campanis decided the 31-year-old Goltz was worth shelling out a six-year, $2.55 million contract that included a $450,000 bonus. It was believed to be the largest contract payoff in baseball history, surpassing the $1.36 million the Dodgers paid to relief pitcher Don Stanhouse in 1979. Both Goltz and Stanhouse became L.A. poster boys for free-agent busts. Goltz was waved less than three seasons into his deal and still paid $1.5 million, some of it after he was retired. The Dodgers may have still been dazzled by his 20-win season with the Minnesota Twins and 39 starts in 1977 (where he threw a ridiculous 303 innings). But he posted seasons of 7-11 with a 4.31 ERA in 1980 (giving up 198 hits in 171 innings with only 91 strikeouts), 2-7 with a 4.09 ERA in a World Series team of ’81 (throwing just 77 innings, plus giving up two earned runs in 3 1/3 innings work in the Fall Classic and given a World Series ring) and an 0-1 start in two games of ’82 before he was released. That made for a 9-19 performance and 4.26 ERA. Picked up by the crosstown Angels (wearing No. 30), with the recommendation of manager (and former Twins skipper) Gene Mauch, Goltz and happened to post an 8-11 record for the rest of ’82 and ’83 while the Dodgers were still paying him. In that time, Goltz pitched for the Angels in the AL playoffs against Milwaukee and was released afterward with a torn rotator cuff. In his Society of American Baseball Research biography, writer Lee Temason noted that Goltz’s “recollections about the Dodgers years were that Manager Tom Lasorda did not do much ‘managing.’ Coaches Monty Basgall and Danny Ozark really ran the team. The Dodgers still had the outstanding infield of Steve Garvey, Davey Lopes, Bill Russell, and Ron Cey. They were strong on offense, but Goltz says that Lopes and Cey had little range.” Take it for what it’s worth.

We also have:

Todd Worrell, Los Angeles Dodgers relief pitcher (1993 to 1997)

Geoff Zahn, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1973 to 1974); California Angels pitcher (1981 to 1985)

Joe Moeller, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1962 to 1967); Also wore No. 27 in 1968 and No. 25 from ’69 to ’71

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 38: Leon Burns (and Brian Banks)”