This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 70:

= Marv Marinovich, USC football

= Joe Madden, Los Angeles Angels

= Rashawn Slater, Los Angeles Chargers

= Harry Smith, USC football

The most interesting story for No. 70:

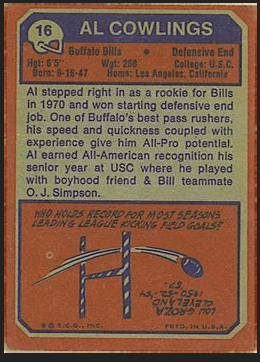

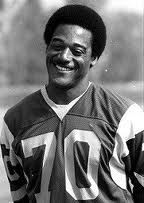

Al Cowlings, Los Angeles Rams defensive end (1975 and 1977) via USC (1968 to 1969)

Southern California map pinpoints:

USC campus, Los Angeles Coliseum, L.A. Superior Court, Hollywood, Brentwood via the 405 Freeway

Esteemed universities vested in the time-honored tradition of slapping names onto fancy buildings based on the whims of a wealthy donor will, at some point, have to justify a problematic choice.

Embedded in the thematic USC Village, the Hogwarts-eque collection of brick buildings that appear to be left over from the Harry Potter movie set, the Cowlings Residential College provides more than 700 rooms to sophomores, junior and seniors who, according to their parents, often cross the street to take classes on the campus that was established more than 100 years ago with for-real old buildings just south of this domestic tranquility.

That’s Cowlings, as in Al “A.C.” Cowlings.

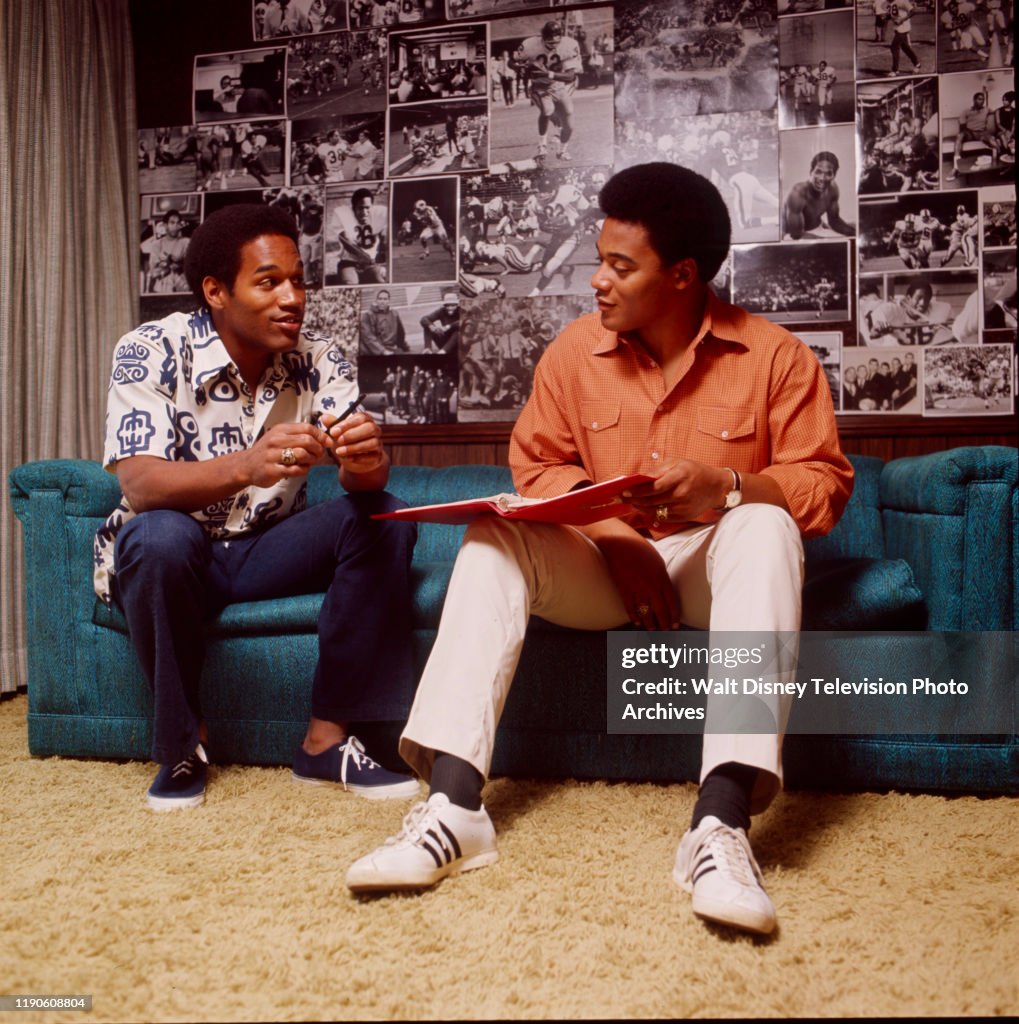

His contributions to the school: Two years in the late ‘60s as an All-American football player. Hung out with a group of guys known as “The Wild Bunch.”

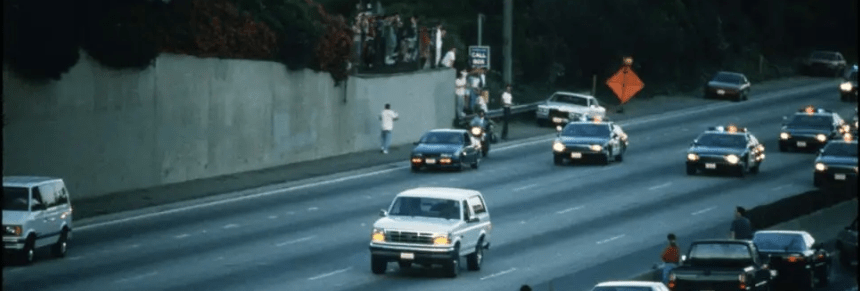

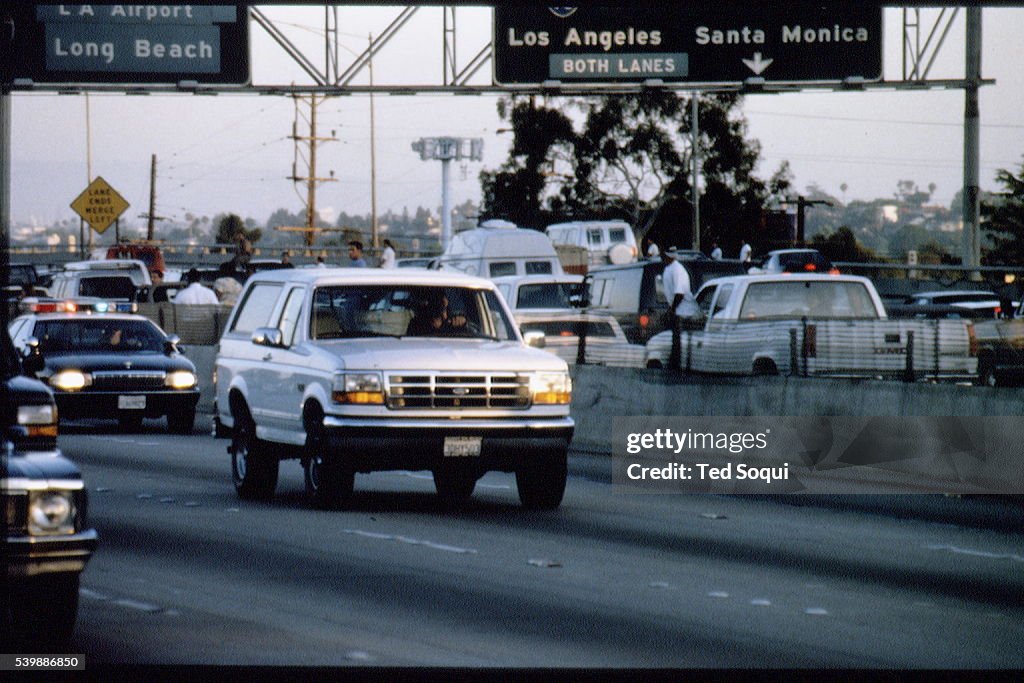

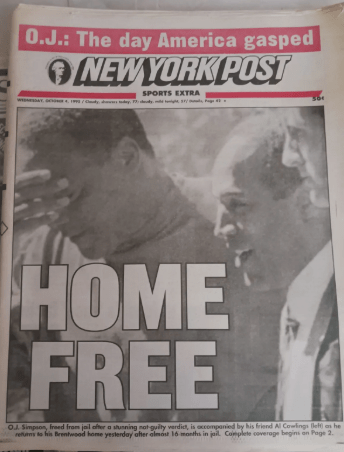

And before there was such a thing as ride-sharing services, Cowlings was the OG uber-Uber driver with his snappy white Ford Bronco, just a scream away from his best friend, O.J. Simpson. To wit, Cowlings once screamed through a cell phone to police in 1994 commandeering said vehicle in the most bizarre slow-speed car chase through Southern California: “My name is A.C.! You know who I am, goddammit!”

In the back seat was an emotionally unstable Simpson, which Cowlings said had a gun to his head.

Long, strung out documentaries, historical recreations for TV and volumes of published tell-all books have dissected the timeline where this incident fell on June 24, after Simpson was supposed to surrender himself to police as the primary suspect, based on evidence collected, in a double-stabbing murder of his former wife, Nicole Brown, and her friend, Ron Goldman.

A lot of it got rehashed and retrashed when when Simpson died in 2024. It now leaves Cowlings as the one to obfuscate whenever a spotlight returns to this sorrid saga.

But how this all happened — how A.C. and O.J. became BFFS — has its foundation in the ways teammates form a bond on an athletic field to achieve a common goal.

Jump in the car and we’ll explain as we’re driving.

The context

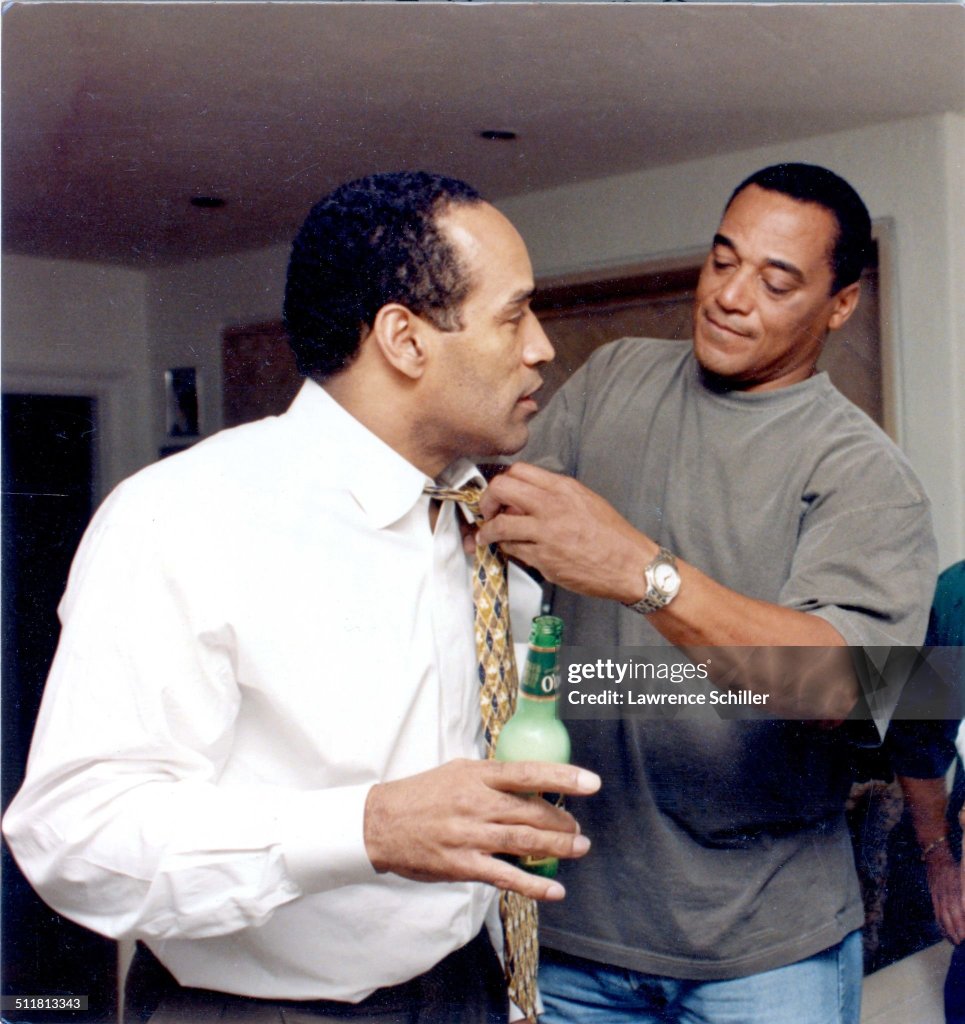

Where ever O.J. Simpson went, A.C. Cowlings was close by.

As a wing man, a body guard, an errand runner, a de facto big brother — born in June of 1947, less than a month before Simpson.

Mostly, Cowlings idolized Simpson.

Cowlings recalls meeting Simpson for the first time as third graders at Patrick Henry Elementary as they were surviving the reality of the low-income Potrero Hill neighborhood of San Francisco.

“I didn’t like him then,” Cowlings said. “But then most of his close friends didn’t like him either. It was his personality. He was a half-way bully.”

Cowlings said he and Simpson used to go to the old Fisherman’s Wharf, climb beneath the old condemned pier, take a broomstick with a spear taped to the end, and stab perch as the school swam by. They took their catch back to the projects and sold them. They would also go to 49ers home games at the old Kezar Stadium, scrounging up 10 cents to catch the bus, and find people who would give them extra tickets.

“We would turn around and scalp them — we had all kinds of way of making money in those days,” Cowlings boasted.

In junior high, he and Simpson formed their own “protection agency.”

“We’d scout around school and find someone who was weak,” Cowlings said in 1968. “Then we’d get someone to push him around a little. After that we’d come up and ask the kid if he needed protection. If he said no, the same guy would come back and push him around some more. We’d keep it up til he paid, maybe 25 or 50 cents. But we never hurt anybody.”

All in fun.

At Galileo High, when Simpson and Cowlings played football together, there was no question that “O.J. was the leader,” said Cowlings. “He always stood out. He was the spokesman. Whenever we got into trouble in high school, if they wanted to talk to any of the group, it would be O.J. He was the main man then, too. If you were playing any ball in the neighborhood, he was the No. 1 guy to get on your team.”

But Cowlings also said in a 1969 interview: “I got my nose busted a number of times on account of him. You see, O.J. had a habit of promoting fights with guys from other neighborhoods, and then disappearing.

“There was the time the two of us went to watch a high school playoff game. There was a certain lady who was supposed to have eyes for me, and O.J. was telling her I had eyes for her, which was not exactly the case. Anyhow, she told her boyfriend that I was digging her and right after the game, there’s a tap on my shoulder, and the boyfriend and two of his buddies let me have it.

“O.J.? He was nowhere to be seen.”

Three games into their senior season at Galileo High — three losses to be specific — Simpson remembers when their coach was so upset with them all he threatened to bench all the seniors and play only underclassmen the rest of the way if they lost their next game to undefeated St. Ignatious.

“We were on a bus, Al Cowlings was sitting next to me and the coach was chewing us all out,” Simpson recalled in 1968. “I remember telling Cowlings, ‘I don’t care if we win or lose, do you?’ He turned to me and said ‘So what.’ And I said ‘So what’ back.”

In the fourth quarter of that next game, Simpson, playing defensive back,took the ball out of the receivers’ hands in the fourth quarter, turned around, and raced 60 yards for a touchdown to clinch a 31-26 win.

While in high school, Cowlings wanted to date a girl named Marguerite Whitley. But since Cowlings battled a stutter, he had Simpson deliver the lines for him. One time when they had some relationship issues, Simpson stepped in as a mediator.

“Well, O.J. told her things all right, but he would up spinning more yarn for himself than he did for Al, and Marguerite ended up with him,” said former Galileo teammate Joe Bell.

By 1967, Simpson and Whitley married.

Cowlings may have been upset about how the whole thing turned out, and tried to roll the couple’s car over. But he had accepted this reality.

When they graduated from high school in 1965, Cowlings and Simpson went together, again, to City College of San Francisco to continue playing football. Simpson set a junior college record with a 304-yard rushing game.

And before where was any sniff of the Rose Bowl, the two drew attention twice in the annual Prune Bowl.

In the ’65 game at San Jose State, Simpson, on a bad knee, scored three touchdowns in a 40-20 over Long Beach City College. In ’66, CCFF lost to Laney College, 35-13, for the mythical state community college title before an estimated 12,000 fans at Spartan Stadium. Simpson was held to 26 yards on 14 carries.

USC won out for the prized running back for his last two seasons of eligibility. Cowlings was eventually part of the package deal.

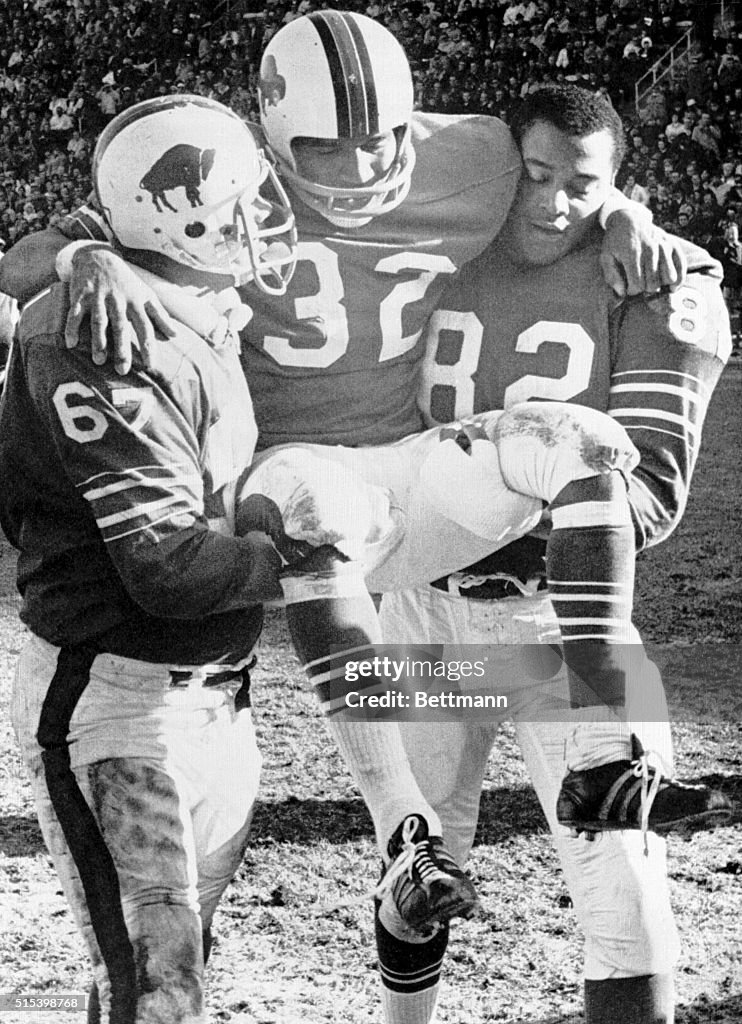

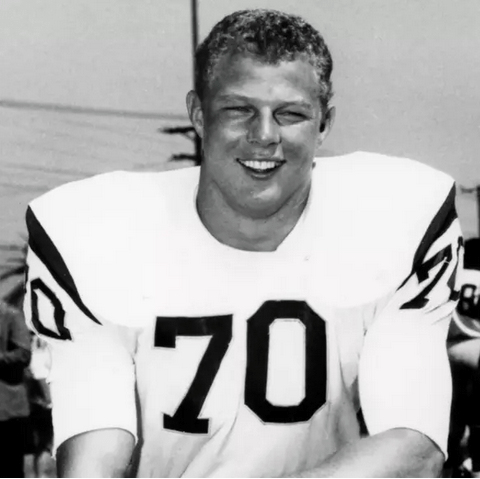

While Simpson’s time at USC in ’67 and ’68 included winning the Rose Bowl Player of the Game as a junior and the Heisman Trophy in his final season, Cowlings, wearing No. 72, fell back a grade and put in his two seasons in ’68 and ’69. He was second-team All-Pac 8 in ’68 and first-team All American in ’69. USC went to the Rose Bowl both times, posting a 19-1-2 record over that period.

The only Rose Bowl that Simpson and Cowlings played together with USC was the Jan. 1, 1969 loss, 27-16, to No. 1 Ohio State, the de facto national championship game. Simpson ran for 171 yards and an 80-yard touchdown run, but USC had five turnovers, including one of his fumbles. Cowlings was moved to defensive end for the first time that season because of an injury to Jim Grissum and the Buckeyes exploited that, said McKay.

In that time frame, “The Wild Bunch” came into being. The Trojans’ defensive line of Cowlings, Charlie Weaver, Jimmy Gunn and Tody Smith (the younger brother of Bubba Smith) was its own Saturday version of the “Fearsome Foursome” that the Los Angeles Rams kept replenishing in its Sunday visits to the Coliseum. This group was nicknamed after the 1969 Western made by Sam Peckinpah by the same name, starring William Holden, Ernest Borgnine and Robert Ryan.

Cowlings gave the group its branding.

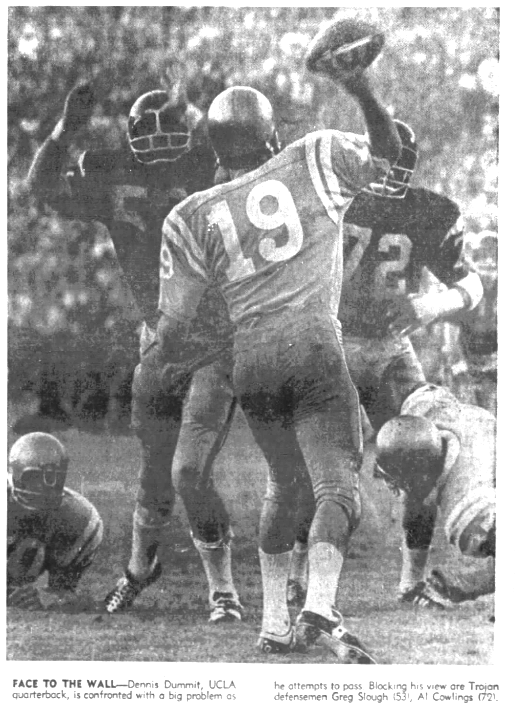

USC’s line bunched together a conference-low 95.6 yard rushing a game and only 2.3 yards a carry. It made its biggest impact in the ’69 USC-UCLA game, bouncing Bruins quarterback Dennis Dummit “across the Coliseum floor like a double dribble,” wrote Sports Illustrated’s Dan Jenkins. Dummit was sacked 12 times and intercepted five times as the Trojans won, 14-12.

The story also noted that students carried banners that said “The Wild Bunch Takes No —- !”

For the ’69 season, Simpson was already a star rookie with the Buffalo Bills, their No. 1 overall pick in the NFL Draft. When the underperforming Bills had the No. 5 overall pick a year later, they banked on Cowlings, a prime specimen at 6-foot-5 and 255 pounds in a ’70 draft that was not a real star-studded affair. Of the 442 players picked over 17 rounds, only No. 1 overall pick Terry Bradshaw, taken by Pittsburgh, made the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Cowlings’ fame and notoriety would come in due time.

Cowlings lasted only three seasons in Buffalo, was traded to Houston the year before Simpson put up his 14-game NFL regular season record of 2,003 yards rushing and eventually the Oilers released him after he suffered a terrible knee injury. Cowlings went looking for work.

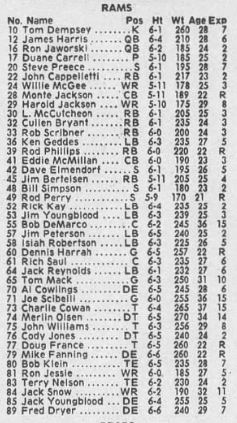

In November of ’75, the Los Angeles Rams decided they needed the help of the 28-year-old. They had lost defensive tackles Larry Brooks and Bill Nelson with knee injuries and were down to rookie Mike Fanning.

Cowlings played the last five games of the season on a Chuck Knox’s team that finished 12-2 and lost the conference championship to Dallas. In a revived 3-4 defensive alignment, Merlin Olsen shared the front line with Jack Youngblood and Fred Dryer, and Cowlings backed them up.

They gave Cowlings No. 70.

Cowlings’ knee had been better as he worked rehabbing it with L.A.’s famed Dr. Robert Kerlan.

“I know I can still play ball with the best of them,” Cowlings told the Los Angeles Times in December of ’75. “Dryer and Youngblood are playing super ball and I have no argument sitting on the bench. The Rams know I’m ready if I’m needed. I’m just really tickled to be back. I guess everything has a way of working out. I’ve never been on a winning pro team before and now I am. My heart is back in the game now.”

In July of 1976, reports came out that Simpson was tired of playing in Buffalo and was pushing for a deal on the West Coast — closer to his home, his movie aspirations, his endorsement deals. Cowlings was quizzed about what was happening — and if he could help orchestrate a reunion with Simpson playing for the Rams. He said he wasn’t trying to influence Simpson.

In 1976, the Rams cut Cowlings just before the start of the regular season as he lost his position to Cody Jones. Cowlings found a roster spot with the expansion Seattle Seahawks.

He circled back to the Rams for 1977 and got into all 14 games — Knox’s 10-4 team still had Dryer and Youngblood, but Olsen was retiring. No. 70 was back in business.

“It’s like any other situation in life,” said Cowlings at the time. “You just try to rise to the occasion. It’s like last season when I was cut at the end of preseason, then that’s the way it’ll be. The Rams have always been very honest with me.”

Cowlings’ one stat for the Rams that season — a fumble recovery — was proof he did play.

At a time when Cowlings was trying to keep his roster spot with the Rams, he did an interview with the Los Angeles Times at the team’s Cal State Fullerton training camp in the summer of ’78 that probed more about the relationship he had with Simpson. The headline on the piece could have seemed rather demeaning: “Cowlings Lives Life in the Shadow of O.J.”

But as Cowlings pointed out, there was value in being Simpson’s friend versus actually being Simpson.

“It doesn’t bother me at all,” Cowlings said. “I’m able to enjoy myself. O.J. can’t really go out and enjoy himself without people coming up to him constantly … The Lord didn’t stop when he gave O.J. ability. He made him a good person, too.”

Cowlings reconciled how when he was with Simpson, people naturally thought he was a hired bodyguard.

“Back East, so many people have them,” Cowlings said. “Or they’ll assume that I’m O.J. because I’m taller. They have this image of a football player being very large. They’ll come up to me, ‘Aren’t you O.J. Simpson? … Are you his brother?’”

After the Rams cut Cowlings again before the ’78 season, he ventured off to the Canadian Football League’s Montreal team.

In 1979 came one more reunion — Simpson and Cowlings played their last pro season together with the San Francisco 49ers.

That’s also the year O.J. and Marguerite divorced. Simpson had already been dating Nicole Brown, 12 years younger than him. Simpson and Cowlings had the next chapter of their life to consider.

“I’ve never driven across the United States,” Simpson said. “Al Cowlings and I are going to fix up a bus into a mobile home, take two gorgeous ladies, and drive across the country.”

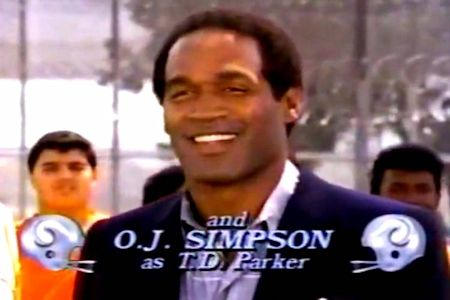

Acting became the next tag-team project. Both were in the HBO sit-com “1st & Ten,” launched in 1984 and lasting six seasons (Simpson’s character was T.D. Parker for the full run; Cowlings’ character, Coach Nabors, got into 12 episodes over three seasons).

As Simpson’s movie and TV career grew, along with his opportunity to do commercials and get involved in broadcasting, Cowlings was close by, finding work as a technical advisor on the football scenes in the 1991 film “The Last Boy Scout” and for “Rudy” in 1993.

Cowlings was the natural pick of Simpson’s best man when he married Nicole Brown in 1985.

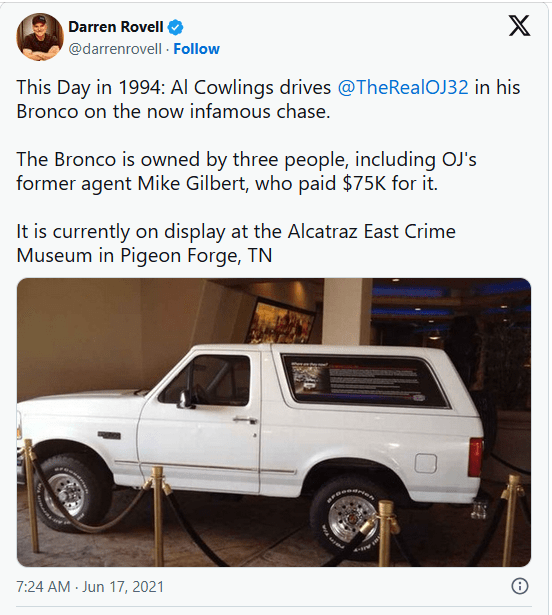

Eventually, Cowlings and Simpson also both owned white Ford Broncos. The 1993 model seen by nearly 100 million TV viewers in the summer of ‘94 belonged to Cowlings.

Simpson and Brown had divorced in 1992. When Brown was found murdered at her Brentwood apartment with Goldman, Simpson became the prime suspect.

He agreed to turn himself into the Los Angeles Police Department on the morning of June 17 after charges were filed. Simpson and Cowlings had been in the Encino home of his friend Robert Kardashian that morning, but when the attorneys were upstairs in a conference, Simpson and Cowlings fled with a cell phone and a gun.

Because Simpson failed to show up by the 11 a.m. appointed time, he was declared a fugitive, wanted on two counts of first-degree murder.

One of his lawyers, Robert Shapiro, discovered Simpson and Cowlings had already left his Brentwood house together. At a 3 p.m. news conference, L.A. District Attorney Gil Garcetti said “anyone helping Simpson flee will be prosecuted as a felon,” so police were then actively searching for Cowlings, issuing an arrest warrant for him by 4:45 p.m.

Cowlings was now risking his own reputation and freedom at Simpson’s expense.

Simpson was reportedly making 911 calls from a cellphone in Cowlings’ Bronco as the two were on Interstate 5 in Orange County near Lake Forest, having left the gravesite where his ex-wife was buried days earlier.

TV helicopter cameras picked up the car near 6 p.m., near the El Toro Y. The pursuit was on as dozens of police cars followed for two hours. Friends and colleagues of Simpson phoned radio and TV stations to try to talk Simpson from killing himself, as if he could hear them from Cowlings’ dashboard radio.

One lawyer at the time called it “the day Los Angeles stopped.” TV viewers, as well as the city’s residents, somehow felt they had a vested interest in the outcome.

Cowlings pulled off the Sunset Blvd. exit of the 405 Freeway in Westwood and headed West toward Simpson’s Brentwood home.

Cowlings then acted as the mediator for the surrender.

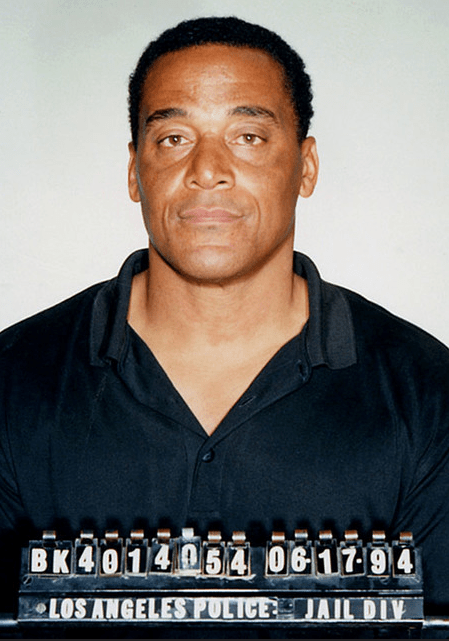

Both Cowlings and Simpson were arrested and at L.A.’s Parker Center by 9:30 p.m. Cowlings was charged with aiding and abetting a fugitive, a felony. He was released on $250,000 bond. Simpson was not allowed bail.

Cowlings now had a new number: BK4014054.

Charges against him were eventually dropped by district attorney Gil Garcetti because of “lack of sufficient evidence.” Cowlings’ lawyer, Donald Re, had argued that instead of accusing Cowlings of a crime, he should be seen as a hero.

“This man risked his life to try to save his friend and he did it,” Re said in 1994. “I am afraid if he had not intervened, O.J. Simpson would be dead.”

After the eight-month “The Trial of the Century” played out in downtown L.A. from January to October 1995 — introducing the world to Judge Lance Ito, house guest Kato Kaelin, lawyers F. Lee Bailey, Marcia Clark and Johnny Cochran, crooked police officer Mark Fuhrman and the kingpin of the Karsashian brood, amidst all sorts of distractions and reactions — Simpson was acquitted of the murders.

Photos of Cowlings at his home showed him reacting with relief and exhilaration.

But it wasn’t over. A civil trial filed by the Goldman and Brown families against Simpson in 1996 required Cowlings to partake in a deposition, just as he had to do for the criminal case.

Cowlings admitted that when he had been back at Simpson’s place on Rockingham Drive, “the house reminds me a lot of Nicole, and it bothers me” that she was dead. “Nicole was very instrumental in doing a lot of things around the house, designing it, the layout about it, the pool, and to sit there and — you know, it’s a difficult thing. … I miss her. She was very close and very dear to me.”

Cowlings also said that if anyone asked him if Simpson “did it,” he replied “No.” He also would not disclose his whereabouts in the time between the murder and the freeway chase.

Simpson was found responsible for the deaths in that trial in 1997 and responsible for a $34 million payment.

Cowlings has never said much, if at all, on the record, decades later about that wild ride through L.A., if Simpson confessed anything to him or anything new, even after Simpson’s death at age 76.

The only bizarre action on Cowlings’ part was when he showed up one day at Simpson’s criminal trial and held a press conference in the back of the courthouse with his attorney, Donald Re. Cowlings said he set up a 900-number where, at $2 a minute, people could ask him questions about anything — except the murder and the trial.

Was this to help pay any legal fees he expected to incur? Who knows.

His ’93 Bronco was purchased by Simpson’s former agent, Mike Gilbert, and kept in a parking garage. In 2017 it was loaned to something called the Alcatraz East Crime Museum, displayed as part of an exhibit on the murder trial.

The question many still ask: Was Cowlings loyal to a fault with Simpson?

“If O.J. could depend on one guy, it was A.C.,” said former Los Angeles Rams general manager Don Klosterman in 1994 after the freeway incident. “There was loyalty. I’m sure A.C. (didn’t) even think he was breaking the law.”

One psychologist interviewed as to why Cowlings would put himself at such a risk for a friend called it a “Butch Cassidy and Sundance Kid” type of relationship.

Depends on how you’ve decided to watch the back of someone you hope would always be there to make sure you’re a partner in crime someday if you needed it. Kind of like having your own protection agency.

The legacy

Cowlings was inducted into USC’s Athletic Hall of Fame — 15 years after the notorious freeway chase. His bio noted that, after his playing career, “he became a businessman and actor.”

It can be updated to include how he has his NIL attached to the dorm room near campus.

At the $700 million facility that houses up to 2,700 students amidst trendy super markets and coffee shops, the Cowlings Residental College is said to focus “on the arts and culture of Los Angeles. The 344 residents of this college explore the many musicians, filmmakers, fashion designers, painters and various artists from around the world who have made L.A. their home. … the residents will be surrounded by a wealth of experiences that will enrich their learning experience and help them find their niche within USC and the City of Angels.”

The naming rights were secured by a $15 million anonymous private donor. It has been speculated that the gift came from Cowlings’ close friend and eventual employer, Wayne Hughes, a USC alum who founded Public Storage, was instrumental in helping Lynn Swann become the school’s athletic director for a short time, and died in 2021. Hughes had donated about $400 million to the university — nearly all of it anonymously.

“This remarkably generous gift enhances USC’s world-class living and learning environment and will carry Mr. Cowlings name, in tribute to his tremendous passion for his alma mater and for our students,’’ said USC then-President Max Nikias in a statement in 2017.

Again, this is more than 20 years after Cowlings’ connection as Simpson’s accomplice. It’s not as if the name was put on the building and decades later he became a nefarious figure in SoCal history.

Cowlings hasn’t explained how his name became part of the updated USC campus brochure, or what he is required to do as the building’s namesake. Maybe he can pile students’ parents into his car and take them on the Simpson Brentwood Tour, as locals had to do for years with out-of-town guests infatuated with the murder case.

Cowlings will show up at various USC football games in support of events or asked to be on the field with families of former players.

He always seems to be around. Just trying to be of help to someone.

There’s a quote Cowlings gave back in that Rams camp interview of 1978, where he explained how he wasn’t interested in keeping his name in the news, but looking to be of service with the hope that karma would come back to reward him.

“I’ve always been a firm believer that if I can help somebody, fine, but I’m going to get mine regardless,” he said. “I’m not looking to make a killing.”

Who else wore No. 70 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

Marv Marinovich, USC football two-way lineman (1959 to 1962):

Captain of John McKay’s ’62 team and voted Most Inspirational on a squad that won the Rose Bowl and national championship, Marinovich matriculated to USC via Santa Monica Community College after prepping at Watsonville High in Santa Cruz. Lettering in ’59, ’61 and ’62, Marinovich’s senior season saw the Trojans finish 11-0. He was USC’s Player of the Game after a 14-3 win over UCLA. The Los Angeles Rams took him in the 12th round of the 1962 NFL Draft. Even though the Oakland Raiders picked him the 28th round of the ’62 AFL Draft, he went with Oakland — and only played one game. As a strength and conditioning coach, Marinovich would attract more headlines later in life for the methods he used to nurture his son, Todd, as a budding a quarterback in Orange County and then at USC. And then the Raiders in the NFL.

Harry Smith, USC football left guard (1936 to 1939):

The story goes that Smith was about 15 and playing football at Chaffey High in Ontario when he went to the movies one afternoon in 1931 and, before the feature attraction, was enamored with the newsreel highlights of USC’s 16-14 upset victory over Notre Dame from that November. From then on, he dreamed of someday playing for the Trojans. He enrolled in 1936, was the freshman captain in 1937 and became a three-year starter at guard on the varsity. The two-time All-American known as “Blackjack” for the cast he wore on one hand during his senior season was inducted into the Trojans’ Athletic Hall of Fame 44 years after he was made one of the early members of the College Football Hall of Fame in 1955. Smith was on the ’38 team that beat Duke in the Rose Bowl. The next year, he led the Trojans to a win over Tennessee in the Rose Bowl to win a national title. After playing in the 1940 College All Star Game, his one season in the NFL with Detroit earned him a Pro Bowl selection. He was a USC assistant coach in 1949 and ’50.

Rashawn Slater, Los Angeles Chargers offensive tackle (2021 to 2025):

As the Chargers’ first-round pick (13th overall) in the 2021 draft, the 6-foot-4, 304-pounder earned a Pro Bowl start as a rookie and was back in the Pro Bowl in ’24. In July of 2025, he signed a four-year, $114 million extension that includes $92 million guaranteed and made him the highest-paid offensive lineman in NFL history. A week later, he tore a left patellar tendon during a training camp drill and was ruled out for the entire season.

Have you heard this story:

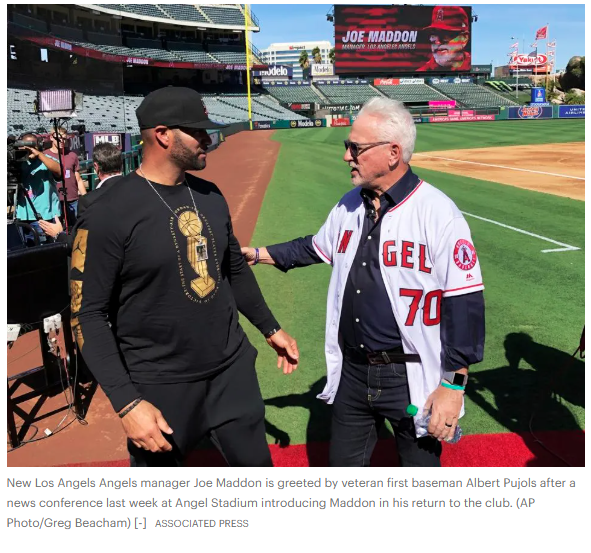

Joe Maddon, Los Angeles Angels manager (2020 to 2022); California/Anaheim/Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim coach (1994 to 2005)

By the time the Angels hired Joe Maddon to be its manager in 2020, which turned out to be a unique navigation through the COVID outbreak, some may have forgot that he had three instances of managing the team back when he was enlisted as a coach for more than 30 years.

His permanent record lists him with a 8-14 run in 1996 — he had to step on an interim basis for John McNamara, who had health issues after he had already been summoned to replace Marcel Lachemann as the skipper. Yes, the Angels of that time could cause managers fall ill. Maddon also had a 19-10 mark during the last month of the 1999 season, filling in after Terry Collins resigned. Yes, the Angels of that time could cause managers to quit. Maddon is also credited with winning a game in 2004 as a fill-in for a suspended Mike Scioscia.

A catcher in the Angels’ organization who never went higher than Single A, Maddon stuck around when the Angels gave him a job as a scout, a minor-league skipper and a roving hitting instructor. After he was given a spot with the big-league team in 1994, he was Scioscia’s right-hand man during their 2002 World Series run. Tampa Bay hired Maddon as its manager in 2006, and he won the first of two AL Manager of the Year Awards when he got the Rays to the 2008 World Series — as he was wearing No. 70. When that contract ran out in 2014, the Angels seemed interested in bringing him back, but Maddon matriculated to the Chicago Cubs in 2015, won NL Manager of the Year, and guided that franchise to the end of a 108-year World Series title drought — again, wearing No. 70. When the Cubs didn’t bring him back after the 2019 season, the Angels swooped back in and had No. 70 ready for him, as well as a three-year deal. Maddon wasn’t allowed to fulfill all three seasons, let go early in 2022.

Maddon once explained his version of how he ramdomly ended up wearing No. 70:

In September of 1985, the Angels acquired 40-year-old Don Sutton from Oakland. Through his 16 years with the Dodgers, Sutton of course wore No. 20 (which was retired when he went into the Baseball Hall of Fame). Sutton also procured No. 20 with Houston, Milwaukee and Oakland. But coming to Anaheim, he found No. 20 was already claimed by Garry Pettis, so he took No. 27 at first. In ’86, Sutton was able to land No. 20 eventually after Pettis changed to No. 24.

“I’m in spring training (in 1987) and I had No. 20 — that was my number,” said Maddon. “Twelve was my number in football, and 20 in baseball. All of a sudden, I got back to my locker one day, and I had No. 70 in it. And it was because Mr. Don Sutton, future Hall of Famer, deserved No. 20 before I did. I told our equipment manager afterward that I would never change my number again, because nobody is going to ask for No. 70. That’s how it happened.”

Sutton was released at the end of the ’87 season and outfielder Tony Armas wore No. 20 for the next two seasons. When Maddon was let go by the Angels 56 games in 2022, Phil Nevin took over. Nevin wore No. 20 as an Angels third baseman in 1998, when Maddon was a coach.

We also have:

Emmanuel Pregnon, USC offensive lineman (2023 to ‘24)

Justin Wrobleski, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2024 to present)

Anyone else worth nominating?

2 thoughts on “No. 70: Al Cowlings”