This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 88:

= Tim Rossovich, USC football

= Phil Nevin, Los Angeles Angels manager

= Billy Don Jackson, UCLA football

= Preston Dennard, Los Angeles Rams

The most interesting story for No. 88:

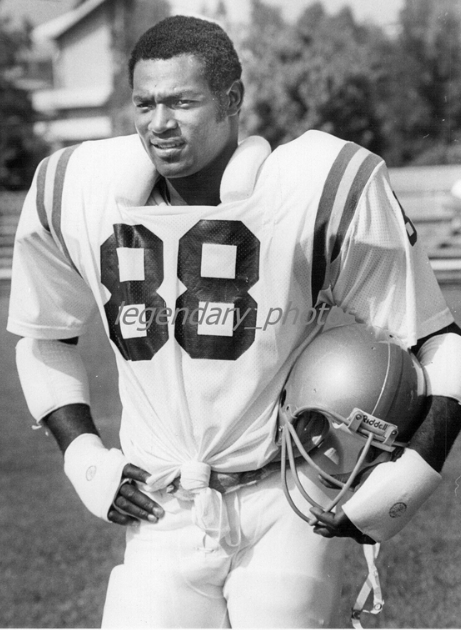

Billy Don Jackson, UCLA defensive lineman/linebacker (1977 to 1979)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Westwood, L.A. Coliseum, Los Angeles Superior Court

All these years later, do you have a better read on what happened to Billy Don Jackson at UCLA in the late 1970s? Even now, it might be wise to review all the evidence.

A heralded high school recruit from football-rich Texas who stepped right in as a freshman starter on Terry Donahue’s UCLA squad, Jackson was voted by his teammates to receive the N.N. Sugarman Perpetual Trophy. It represents the player who exhibited the best spirit and scholarship.

Jackson won that twice. The second time was after his junior season, even after Donahue decided he had to punish him for missing classes with a four-game suspension at the end of the season, sending him to the scout team and effectively ending his college career.

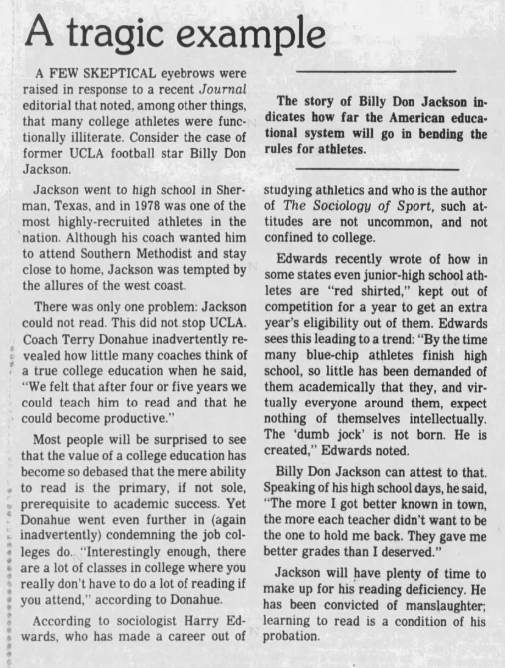

There is also the Jackson who, once he was disengaged from Westwood, stood in Santa Monica Superior Court and heard a judge brand him as a “functional illiterate” during a testy sentencing hearing. Jackson had pleaded no contest to involuntary manslaughter in a botched drug deal.

“This young man cannot even read ‘see Spot run’,” the judge, Charles Woodmansee, continued in his diatribe.

“My God,” added prosecutor Marsh Goldstein, “they brought this kid to one of the top universities in the country and it takes a court order for him to properly to learn to read and write. … Billy Don Jackson is himself a victim — a victim of the shoddy system we call intercollegiate athletes. Hopefully somebody in college sports will learn something from this tragedy.”

Jackson became the humiliating yardstick for everything perceived wrong with college sports and a winning-at-all-costs approach. How someone could spend that long at a major university masquerading as a so-called “student-athlete” was a huge red flag.

UCLA took it as a gut punch. College sports took it as a wake up call, beyond simple damage control.

The truth was, and still is, that Jackson had a pronounced reading disability, similar to dyslexia, that was supposed to be addressed by UCLA’s academic department through tutoring and individual attention. It didn’t happen. Who’s at fault?

The collateral damage is that Jackson would be referenced time and again by those outraged about the exploitation of Black athletics at the expense of an education, setting off a sizeable ripple effect for overdue reform.

“The one consistent exception to the negative images presented of Blacks in the media has been the black male athlete,” UC Berkeley sociologist Harry Edwards said in a 1982 L.A. Times story that particularly used the Jackson case as the cautionary tale. “The message, though subtle, is clear: If you are Black and want respect, justice and equality of opportunity and reward from white America, become an outstanding athlete.”

But it really wasn’t that simple for Jackson, despite what may still linger in the court of public opinion.

The context

Sporting a name that sounded like a country western crooner, Billy Don Jackson was born Jan. 29, 1959 and, though trying circumstances, grew into a highly-sought after, 6-foot-4, 280-pound athlete from Sherman High, about an hour’s drive north of Dallas and not far from the Oklahoma border.

Right in the glare of “Friday Night Lights” in Texas football.

Jackson’s college recruitment drew attention unto itself. Bear Bryant at Alabama and Barry Switzer at Oklahoma came calling. Representatives from all the Texas schools urged him to stay home with all sorts of incentive plans. When Jackson played in the 45th Texas High School Coaches Association North-South game in Dallas, it looked like Southern Methodist had the inside track.

To talk to him meant a physical visit to see his mother, Annie. The two lived with his grandmother in a federal subsided $27-a-month upstairs apartment in a housing project. They had no home telephone. Jackson’s parents divorced when he was 3 and he supported his family working full-time in the summer and part time during school.

“He’s only 17 but he’s probably twice that old,” said his high school coach Ed Hunt in 1977 during that recruiting process. “The things he’s going through right now are easy for him compared to what he’s been through. He’s had times when he’s had to worry about feeding his family.”

Jackson came into all with eyes wide open, as a wire service story reported on how he was processing all the sales pitches.

“These guys won’t tell you they’ll give you a car; they’ll be real subtle,” Jackson said. “A couple of them said they’d take care of my homework, give me a tutor, whatever. Make sure I don’t have to go to class, things like that. That ain’t the life for me. Those schools are out of the running. I don’t give them a second look. My father taught me to appreciate a hard day’s work.”

UCLA, trying to recruit more out-of-state talent after Donahue’s first season as a head coach in Westwood, had someone who Jackson could trust. Billie Matthews, a former quarterback at Southern University who coached high school ball in his native Houston, came to UCLA from Kansas in 1971 with head coach Pepper Rodgers and coached defensive backs for one season before concentrating on the running back position. He spoke Jackson’s language.

Aside from bringing Jackson into L.A. on a trip to show off the sunny weather on a day it had been snowing and dreary in his home town, he had a sit down lunch with then-Los Angeles mayor Tom Bradley, a UCLA alum.

In a 2023 interview, Jackson said he picked UCLA so he could get a change of scenery.

“Terry Donahue and Billie Matthews told my mom all she needed to hear,” said Jackson. “That they wanted me to graduate, to get an education, more than just come and be a star football player.”

Jackson trusted UCLA’s game plan.

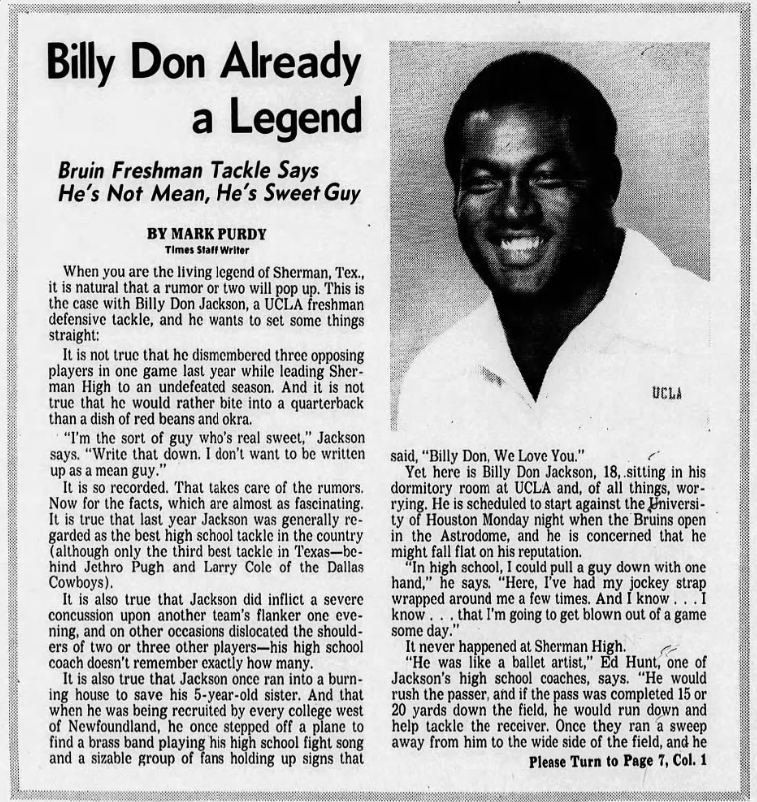

Before the ‘77 season, as players and coaches from the Pac-8 toured West Coast cities in August, one writer at the Sacramento Bee proclaimed: “Sooner or later, Billy Don Jackson will become a public figure. It might as well be sooner. Billy Don sounds as if he could be a character in ‘Semi-Tough’ but in reality he is a mere freshman defensive back at UCLA. Some folks down here guardedly suggest good Billy Don … could be an All-American four years in a row. At the least, he’ll be all-Vicious.”

Jackson told the writers that “my best hit is a clothesline.” He didn’t get his strength from pumping iron.

“No sir, I pumped cotton,” he said.

In one high school game as a senior, Jackson knocked two players out cold.

“They only had to stop play once, though,” he said.

Maybe Jackson eventually realized all the yarn he had been spinning might work against him. Too boastful. He added context.

“I don’t want to be known as a killer,” he added. “You’ve got to remember that for a long time I was just a little, fat kid with a chili-bowl haircut. Sure, I’ve laid out a few guys. And I know some pros say that it’s a dog-eat-dog world so you’ve got to kill a few people. But that’s not my attitude. This is just a game. I like to have fun. I don’t want to be a killer.

“God has plans for me, I’m sure. I’m not sure what those plans are. So I’ve made my own plans. After I finish (at UCLA) I figure I’ll be a pro for maybe about 10 years. Then I’ll have me a business of some kind. That’s it.”

Jackson was also asked how he had been reacting to all the publicity he had been generating back home.

“I don’t read the newspapers,” he said.

Because of injuries to the UCLA defensive line, Jackson started seven games at tackle in his first year, sporting No. 88. His first game was a nationally televised Monday night contest that UCLA lost at Houston, 17-13, in his home state.

“I’m a long way from being satisfied,” said Jackson, who had been UCLA’s only freshman starter in that game. “I was down on myself in the first quarter. I wasn’t coming off the ball as well as I should have.”

Donahue also told reporters after Jackson’s debut: “The best thing about him is his ability to practice hard. His high school coaches (Tommy Hudspeth and Ed Hunt) must have done a great job with him because he acts like he’s been on our practice field for five years.”

The Football News would put Jackson on its freshman All-American team.

In October of 1978, during his sophomore year, Jackson was Pac-10 Defensive Player of the Week after a 45-0 win over Cal as the Bruins improved to 4-0. He had one of 10 interceptions for UCLA in that game, a screen pass he picked off and returned 16 yards for a touchdown, as well has having six tackles, a sack and a fumble recovery.

Up to this point, Jackson’s academic course load focused less on reading and stressed more oral skills — speech, sportscasting, spoken African language.

He also was supposed to be working with a reading therapist as his core requirement classes needed to graduate had been delayed with his electives were now completed. He had already taken incomplete grades in English and sociology.

Adding to that stress, Jackson felt lost when coach Matthews left UCLA after the 1978 season to take a job with the San Francisco 49ers. The man Jackson called “my Rock of Gibraltar” wasn’t there for support as he pointed toward his junior season.

Jackson started to spiral as he moved off campus and fell in with a different crowd, according to teammates. He started skipping classes.

He got into arguments with UCLA coach Jed Hughes, who was trying to transition Jackson from defensive end to linebacker.

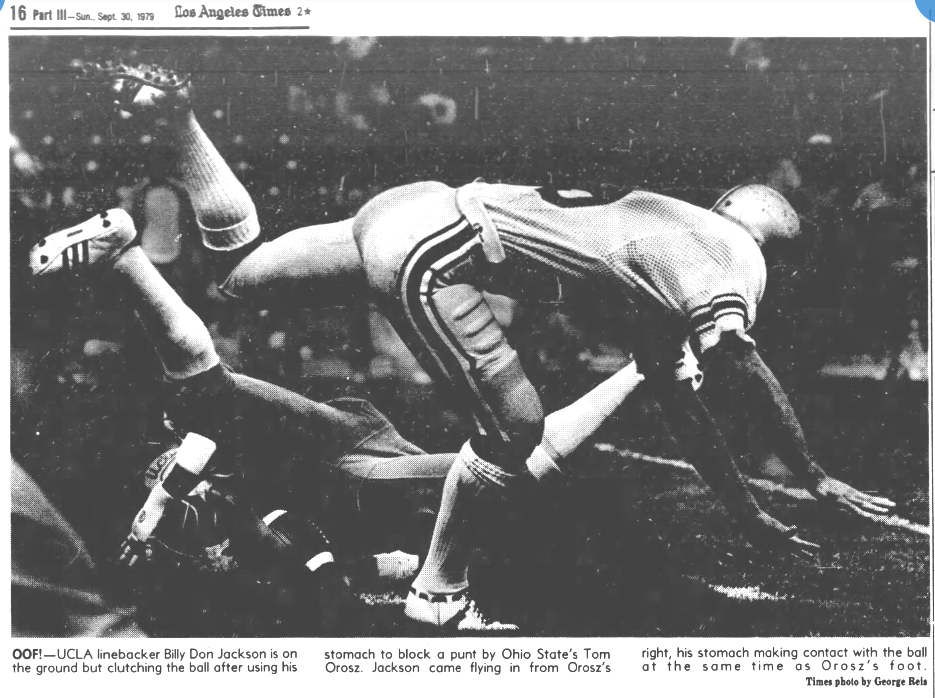

UCLA’s 2-4 start to the 1978 season included a 17-13 loss to Ohio State at the Coliseum, where Jackson’s talents were shown early on during an ABC national telecast when he blocked a punt attempt and recovered the ball in one felled swoop late in the first quarter to set up the first Bruins touchdown.

“Coming down to slam the ball on his foot, Billy Don Jackson!” exclaimed ABC broadcaster Keith Jackson.

“You see Jackson leave his feet — a sensational play,” added ABC analyst and former Arkansas head coach Frank Broyles. “What an effort.”

By mid season, Jackson had tied for the team lead with 62 tackles and led them in interceptions. But when Jackson missed a practice prior to the Stanford game in Week 5 (right after the Ohio State game) and three more practices in Week 8 before facing Washington, Donahue said he felt he had no choice but to suspended Jackson. It would cover the final four games.

Jackson’s excuse is he was looking for a new apartment. But the full scope of Jackson’s issues weren’t obvious.

“Billy Don was having personal problems,” teammate Kenny Easley told the Los Angeles Times. “A penalty has to be directed toward that particular athlete if he didn’t know any of the coaches so that he could receive some help. He just took off on his own. So you have to punish the player because he is hurting the team more than anybody. We look at Billy Don Jackson as one of our defensive leaders and he has some a heckuva job for us. But you can’t allow that (missing practice without permission) to happen.”

Donahue said Jackson could try to regain his final year of eligibility in for the 1980 season. Jackson accepted his role working with the scout team during his punishment, but he thought he would be reinstated for the season-ending game against No. 4 USC. That didn’t happen, and the Bruins were on the wrong side of a 49-14 score, ending their season at 5-6.

“Me not suiting for that game was a total crush,” Jackson would later say. “At that point, I was really hurt.”

Jackson had met with Donahue, football team academic advisor Gene Bleymaier and Skip Johnson of the university’s chancellor’s office in March of ’80 to discuss a chance to redshirt in 1980 and continue on scholarship.

When asked by one reporter: “Is your leaving UCLA pretty cut and dried?” Jackson responded: “No, it’s still wet.”

On top of the academics issue, neither UCLA nor Jackson addressed his on-going drug addiction, which Jackson believes started at a young age with alcohol and marijuana, leading to cocaine and crack.

“It slowly built; it wasn’t just something that happened,” he would eventually admit.

Trying to figure out what to do with idle time, Jackson tried out for Montreal in the Canadian Football League, but nothing came of it. In September of 1980, Donahue and Marvin Demoff, an attorney and UCLA alumnus, arranged for him to transfer to San Jose State, where he could redshirt a year, go to class and play his final year of eligibility.

San Jose State head coach Jack Elway noted immediately that Jackson was missing classes again and would disappear from contact. Elway took away Jackson’s scholarship two months later.

Then came the blindside of a murder charge, exposing his academic deficiencies.

In October of 1980, Jackson came back to L.A. from San Jose for a weekend. Jackson and another man got into a fight with a 20-year-old drug dealer named Mark Bernolak, whom police say was apparently killed over the struggle of a small amount of marijuana. Jackson surrendered. He was arraigned in February of 1981 and pleaded no contest.

After the judge’s humiliating assessment of him, Jackson served eight months of a one-year sentence at the L.A. County jail as well as the Wayside Honor Rancho minimum security in Castaic, where inmates worked on a farm. It was later called the Peter Pitchess Detention Center. He was released in October of 1982.

Jackson was ordered as part of his sentencing to take remedial education courses and improve his reading skills to the 10th grade. Jackson’s issues with substance abuse were also finally addressed despite all his pushback.

“I would never want anyone to go to jail,” Jackson later said. “Jail is not the way to learn. I want to learn. Being in jail made me realize there’s a hell of a lot more in life.”

Jackson explained more in a 1982 interview that while he could read simple words on a page, “I can’t read an English book or a geography book or political science. When you can’t read well and you get words like ‘bureaucratic board,’ it’s a little hard to figure out.”

He said when he thinks about how he was taught in grade school, he became belligerent when teachers offered to help him read.

“I think everybody was sort of scared of me. I didn’t want to read. And point blank, I wouldn’t ‘cause I was bigger than my teachers.”

At the time of Jackson’s arrest, several came out and spoke to his gentle nature.

“The tragedy is that not only was Billy Don a great athlete, but that he had a great spirit and great leadership and great compassion,” said former coach Doug Kay.

Donn Swanbom, another former coach of Jackson’s at UCLA, said: “It might have been the bright lights and fast pace life in L.A. that did him in. It is easy to get caught up in the glamour. It’s not like Sherman where they roll the sidewalks up at night.”

Kenny Easley, who came to UCLA the same year as Jackson, called him “a very affectionate, loving and kind person … I always held Billy Don in a very high esteem.”

Because of Jackson’s highly publicized story, he was continually held up as the prime example of how Black athletes had become collateral damage in the billion-dollar college sports world. Jackson became “a tragic example” of how a “dumb jock is not born” but created.

Sportscaster Howard Cosell was quoted in a story for the Rochester (N.Y.) Democrat and Chronicle, which started as a critique of UCLA’s basketball program under John Wooden and bled over into other sports on the campus:

“Big-time college athletics is garbage and it should be abolished … It’s a tragedy, a blot on the conscience of this nation … How many scandals can college athletics endure? Billy Don Jackson cannot read or write simple English, yet he would have been a junior at UCLA. The judge (in his murder trial) ordered Jackson to take a remedial program so that (his) inability to read and write would never again embarrass him. After something like that, how can anyone claim that the primary concern of a college athletic program is educating its athletes?”

National writer Robert Lipsyte did a longer piece about the state of college sports, again highlighting Jackson’s plight, going back to how the injustices go back to the high school level as well before they are pushed forward to college.

“Because Jackson is black, it was assumed that sports was his best, if not only, chance to make it America,” wrote Lipsyte. “Billy Don Jackson’s story is a worst case scenario only because someone died. The story gets better as soon as he is arrested and taken out othe control of the coaches … He still seems better off than he was in the days when his teammates called him ‘Billy Dum-Dum.”

UCLA coach Matthews continued to defend Jackson and would say about him: “Billy Don worked at his studies. He had tutors and he put in the time. He just had trouble reading … I challenge anyone who says Billy Don is dumb. Play him in chess or backgammon sometime.”

The 77th NCAA Convention in San Diego addressed this because “people feel college athletics are a cesspool, a system of cheating,” said Judy Holland, UCLA’s senior assistant athletic director. “And the public thinks we think it’s OK.”

In 1983, Jackson was free to pursue a pro football career, and Donahue wanted to help. A tryout with the NFL’s Philadelphia Eagles, thanks to Donahue’s connection with head coach Dick Vermeil, the former UCLA coach, didn’t lead to anything. The United States Football League was in business, and the Arizona Wranglers had Jackson’s rights, but the team said he flunked his physical that spring. Donahue next directed Jackson to the USFL’s Boston Breakers and head coach Dick Coury.

Paroled just five months before the season opener, Jackson got a break with the Breakers.

“It was such a rush of emotion,” Jackson said of finally making it, wearing No. 66. “I started shaking. I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. Here I was about to play my first pro game. That was my dream as a kid; now it was coming true. I was scared to death. I had been away so long. … All I kept thinking was, ‘Man, this used to be so easy’.”

In the same interview with the Forth Worth Star-Telegram in 1983, Jackson reflected on his time at UCLA: “I look back at those days and I see a different person. A wild and crazy youngster. A damn fool who had no respect for anyone … the hell with the rest of the world. People tried to talk to me but I wouldn’t listen.”

The aftermath

Donahue would admit in a 1985 Los Angeles Times interview that the whole Jackson incident was as embarrassing for the player as it was for the coach and for the school. Donahue thought the school failed him.

“Billy Don Jackson — years later you can’t escape it,” he said. “Obviously, it was the darkest hour for our program. It was a dark hour for UCLA. I didn’t let him in school, I don’t let anyone in school . . . but I was the head coach, so I was involved. … It was a terrible scenario of events.

“There’s no question that to this day we look back on that situation and the only thing I can do is try to learn from it. The university learned from it. From that point in time, we shifted philosophies. The admission process was ahead of the support process (back) then. There were lots of special action admissions, high-risk students. . . . By support I mean tutorial, curriculum, adjustment of the athletic department to these problems. It was a whole new world, and we were just getting into it.

“Jackson, in a sense, brought everybody to look at that whole process more carefully. In the long run, the tragedy of Billy Don Jackson helped the university. Now the academic process and the support is stronger. It’s so much different and so much better.”

In June 1984, the U.S. Congress held open hearings on “The Consideration of the Quality of Education Obtained by Student Athletes in Large-Scale Collegiate Athletic Programs.”

Saying he wish he “could take that back, but I can’t” when asked about the legal trouble, Jackson said the arrest was “life changing, but in some ways the best thing that ever happened to me. I think if things had been different, I would have turned out much different — a spoiled person, I guess you could say. I’m a very grateful and humble person (now).”

In 1985, the Los Angeles Times documented how a bill introduced to the California state assembly would require all students in grades 7 to 12 to have a minimum 2.0 grade point average in order to participate in extracurricular activities. It would put the state in line with a proposed NCAA regulation of incoming freshman required to have a minimum 2.0 GPA, pass 11 core course and a minimum score of 700 on the Scholastic Aptitude Test.

Again, the case of Jackson and the “functional illiterate” was brought up in why these new rules were being pushed.

“We’re educated people,” said school board president Rita Walters. “How could we be taking advantage of people like Billy Don Jackson? He was used.”

Featured in a 2007 Los Angeles Times interview when he was 48 and living in West L.A., Billy Don Jackson admitted he was sober and drug-free since 1990: “I really believe in my life.” He was his wife, Lori, a UCLA tennis instructor he met at the school, and their two sons, Trevor and Taylor.

In a 2023 video interview he did at a UCLA function, Jackson explained more how he secured a job in Hollywood as a set designer and working in the art department. He has worked on TV shows like “24,” “How to Get Away with Murder,” and movies such as “Jurassic Park” and “Chef,” as well as employing his two sons to work with him in scenery design.

When asked what kind of effect UCLA had on him, he called the “most profound and greatest experience I could never had was here. My life as I know it now would not be the same — good, bad or indifferent. UCLA made a difference for me, to me and in me. The gentle giant you see now is the person I’ve always wanted to be.”

Who else wore No. 88 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

Tim Rossovich, USC football defensive lineman (1965 to 1967):

Chewing glass light bulbs, diving naked into a birthday cake or setting himself on fire, the consensus All American and co-captain on the Trojans’ 1967 national title team was the free spirit who became a Hollywood stunt man for two decades after he carved out a seven-year NFL career. “Tim was the kind of guy who lived on the razor’s edge of rationality and once in a while he would tip off to the wrong side,” said NFL Films president Steve Sabol, who shared an apartment with Rossovich for two seasons. Ron Medved, a former Eagles teammate, added: “People would say to me, ‘Is it true Rossovich …’ I didn’t even let them finish. I’d say, ‘Yeah, it’s true.’ Or they’d say, ‘I heard Rossovich …’ I’d say, ‘Yeah, he did it.’ Whatever it was, I was sure Tim had done it. He was a wild man.” In 1971, Sports Illustrated devoted a dozen pages to Rossovich in a profile entitled, “He’s Burning to Be a Success,” showing off his larger-then-life personality with his bushy hair and Rasputin stare. “I live my life to enjoy myself, I can’t explain the things I do much beyond that,” Rossovich told SI’s John Underwood. “I have more energy than I know what to do with. I can’t just sit around. I get bored. A lot of what I do is silly, trying to cheer people up, trying to cheer myself up.”

Preston Dennard, Los Angeles Rams receiver (1978 to 1983):

Making the Rams squad as an undrafted free agent, he piled up 232 receptions for 3,665 yards and 30 touchdowns in his eight-year NFL career (including Buffalo and Green Bay). He started as the Rams’ top receiver in the 1980 Super Bowl played at the Rose Bowl. He was twice nominated for NFL Man of the Year Award. His top season in L.A. was 1981 when he made 49 receptions for 821 yards and four TDs.

Have you heard this story?

Phil Nevin, Los Angeles Angels manager (2022 to 2023):

If only to post a 119-149 record over a season-and-a-half as a manager for the Angels, it made for a fitting Orange County circle of life for a baseball career that started at El Dorado High in Placentia. After he hit .341 with seven homers as a shortstop on his senior season, taking his team to the CIF-SS 5A title at Dodger Stadium, the Dodgers made him a third-round pick in 1989 that included a $100,000 signing bonus. But Nevin opted for Cal State Fullerton. It was a decision because he wanted to play football and baseball.

On the baseball side: Wearing No. 21, Nevin would lead the Titans to the finals of the College World Series and named winner of the Golden Spikes Award as the top college player. That junior season was also highlighted by taking the Big West Conference Triple Crown — a .391 batting average with 20 homers and 71 RBIs.

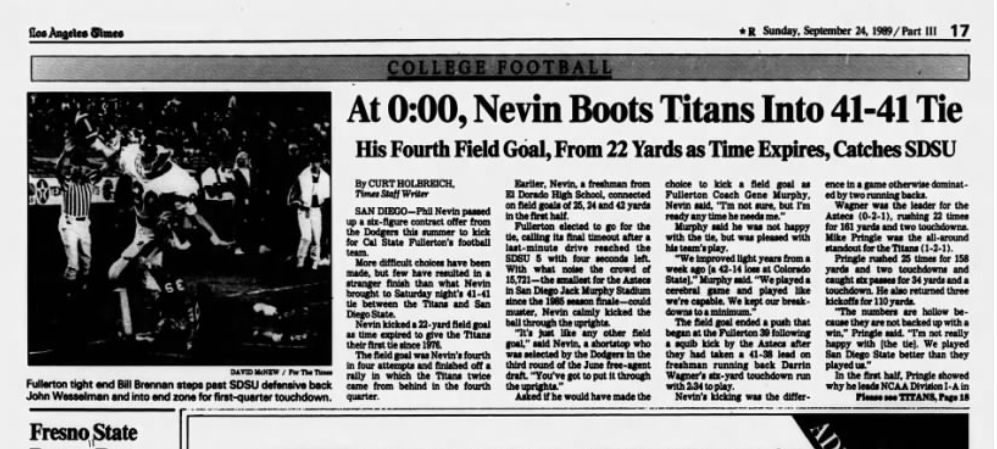

But as a place kicker and punter on the Titans’ football team for three seasons, he led led the Big West Conference in 1989 with 15 field goals out of 21 attempts, including nailing a game-tying 22-yard field goal at San Diego State to secure a 41-41 tie as time ran out at Jack Murphy Stadium, his fourth field goal of the game. He also had a 54-yard field goal earlier that season against Cal State Northridge. Nevin would make all 69 PATs in his career and 31 of 55 field goal tries. In 180 punts he averaged better than 40 yards a kick. Add to that: 3 of 4 passing for 89 yards and three receptions for minus-17 yards.

(Fast forward: Nevin would return to playing home games at Jack Murphy Stadium and hit 41 homers with the San Diego Padres as an All-Star third baseman in 2001).

The starting third baseman on the U.S. Olympic team that finished fourth in Barcelona, Nevin was also the No. 1 overall pick in the 1992 that summer, taken by Houston and finally on the big-league club by 1995. The Anaheim Angels acquired him in 1998 to primarily play outfield, DH and serve as a backup catcher — wearing No. 20, now at a new position he learned while in Detroit. An 12-year MLB career ended in 2007 with a .270 batting average, 208 home runs and 743 RBIs in 1,217 games.

By 2009, he jumped in as manager of the Orange County Flyers of the independent Golden Baseball League, playing their games at his old college field. That led to minor-league manager roles and third-base coaching jobs with San Francisco and the New York Yankees before the Angels brought him in as their third base coach for the 2022 season. When Joe Maddon was let go in June of that season amidst a 12-game losing streak, Nevin was given the interim spot, and the Angels lost again to tie a franchise record with 13 losses in a row. The other lowlight for that season — Nevin was suspended 10 games for his role in a bench-clearing brawl despite the umpires warning about no retaliation pitches. He signed for a full season in 2023. The Angels let him go before the ’24 season as the franchise was dealing with the eminent departure of Shohei Ohtani.

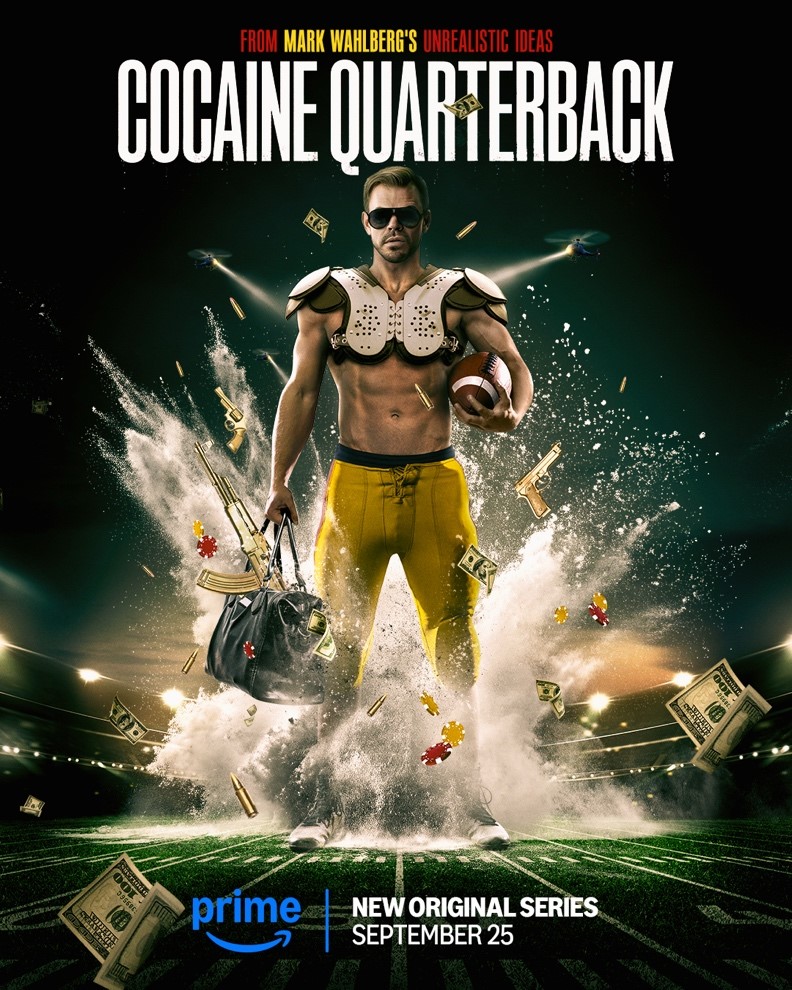

Owen Hanson, USC football tight end (2004):

The 6-foot-3, 225-pound walk-on out of Redondo High came into the football program through the USC volleyball team. He was dropped from the roster during a coaching change, convinced to look at football, made it through Pete Carroll’s tryout, grouped with the rest of the tight ends and had a spot on the Trojans “Leave No Doubt” team that would win a national championship with a win over Oklahoma in the Orange Bowl.

The headlines Hanson generated later in life came from the FBI dismantling his gambling and drug business called O-Dog Enterprises. He was arrested in Australia in 2015 on federal charges of gambling and drug trafficking and wore a new FBI number: 50825-298. After a 2016 guilty plea, he was given a 21-year prison sentence in 2017. The experience has been glamorize with a book, “The California Kid: From USC Golden Boy to International Drug Kingpin.”

An excerpt:

“My first day of football practice, I put my shoulder pads on backwards and didn’t even think to strap them on. … I showed up to the field like the court jester putting on a knight’s armor to elicit laughs from the crowd — and disheveled and looking ridiculous. …”

He was already making trips to Mexico and dealing drugs through his fraternity house, got into steroid use, yet somehow earned the respect of his teammates through hard work on the field. Hanson recounts how Carroll made him a captain for the game against UCLA, which meant he walked out to midfield with Matt Leinart, Reggie Bush and Matt Cassel before the Trojans posted a 29-24 win. The perks of being part of the USC program, from being included in a Maddon video game to having a spot on a “Gladitor of the Coliseum” poster with shirtless and flexing teammates, was as much being part of a Hollywood athletic entourage.

Hanson wrote more:

“One night Matt Leinart took Brandon Hancock and me to a new nightclub called Club LAX. The club’s VIP host took us to the best table, right next to the DJ booth. Six bottle-service girls served us bottles of Grey Goose in whatever cocktail we wanted. Another time, my girlfriend’s dad called me; he was the head of Quiksilver, and he invited me down to tour the company with Matt Leinart. “Do you think you could get me a signed football from him?” he asked. Of course I could. Matt and I were picked up by a chauffeur and taken to the factory, where Matt signed a football and both of us went on a $1,000 shopping spree courtesy of the CEO. These were all the accoutrements of being a modern-day celebrity, and the feeling was intoxicating. …

“I wasn’t one of the top guys. I had walked out onto the field for tryouts and gotten a spot without having played football a day in my life. Simply being a part of the team was a huge accomplishment. Still, getting pummeled day in and day out during practice, I couldn’t help but wonder how good I would be if I had been practicing all my life. I was going against the number one defense of USC every day and getting thrown around like a rag doll, stitches on my chin, concussions. I was tough cannon fodder. Sometimes I’d ask myself, Is that all I am?

“That season we were undefeated, 14–0, and we went on to play the Orange Bowl in Florida, defeating the Oklahoma Sooners 55–19 and winning our second championship in as many years. Over those two years, our record was now 27–1. During the after party, Coach Carroll said, “None of you motherfuckers better be falling asleep tonight. We’re partying until the private plane picks us up.” We did party all night, but I couldn’t help falling asleep. Coach came into my room at nine in the morning: “Hanson, what the fuck are you doing, man? I told you, you got to stay up!” I was toast. Worst hangover of my life. “I’m sorry Coach,” I said, “I couldn’t help it.” He chuckled. “Go on. You’re gonna miss the plane.”

“When I boarded, all my teammates were laughing. Here I was O-Dog, Master of Libations, Mr. Party, Doctor O-Dog with my litany of PEDs and seemingly bottomless sock drawer of drugs, and I was the only guy on the team who passed out and nearly missed the plane. All I could do was smile.

“Pretty soon my reputation was expanding beyond the Heritage Hall of USC. I was quietly making a name for myself in the dark annals of private country clubs, fraternities, college and professional sports circles, and other wealthy and influential cliques. For me, my drug dealing was becoming a master class in networking as I was thrust into a veritable who’s-who of the sports, business, and entertainment world. Down the line, if I got caught speeding along the Santa Monica Freeway with a stash of coke in my subwoofer, I’d pull out my driver’s license with head L.A. Sheriff Leroy Baca’s business card taped not-so-discreetly to the back. He was a huge USC fan and donor, and around town there was a saying called “Friends with Leroy,” which meant if you flashed his business card, you got off.

“Maybe I needed a whole shitload of cash for a large shipment of cocaine that came dirt-cheap because the original buyers had gotten arrested in a sting and my people now had to move the product fast: I could ask for a one-month loan with 20 percent interest from Lou Ferrigno Jr., the movie star’s kid who would front it to me no questions asked. Of course, I’d make thirty grand off that loan in about a week.”

Since Hanson’s release from prison in 2024 and having the book published, Netflix converted the story into a three-part series called “Cocaine Quarterback.” Mark Whicker wrote in his review of the series: “It is a story of desperation and daring, both to extremes, and what happens when a young man sinks into a hole and not only keeps digging, but uses dynamite. … The circumference of “Cocaine Quarterback” is vast and not particularly round. An unskilled director would have left the audience in a thick wilderness, trying to digest all the pieces. … Hanson’s animal instincts keep him alive despite his ignorance of what’s really awaiting him. Hanson is no role model, but he didn’t dodge the consequences that he courted. After all, who among us is inclined to cut our losses, instead of fighting on?” Add to that: The 43-year-old paroled felon had also been earning $500 every two weeks selling the iced protein bars he first learned to make in prison mop buckets.

We also have:

Pat Curran, Los Angeles Rams tight end (1969 to 1974)

Sean LaChapelle, UCLA football receiver (1989 to 1992)

Anyone else worth nominating?

3 thoughts on “No. 88: Billy Don Jackson”