This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 49:

= Charlie Hough: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Tom Niedenfuer: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Dennis Smith: USC football

= Charles Phillips: USC football

= Carson Schwesinger: UCLA football

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 49:

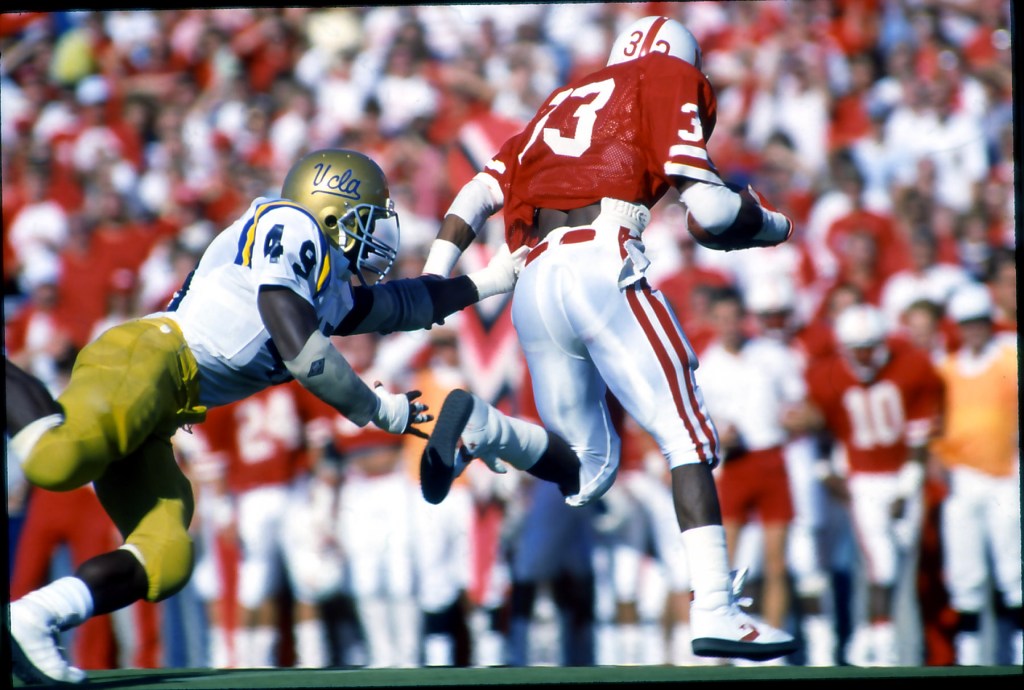

= Marvcus Patton: UCLA football

The most interesting story for No. 49:

Marvcus Patton, UCLA football linebacker (1985 to 1989) via Leuzinger High of Lawndale

Southern California map pinpoints:

Inglewood, Lawndale, Westwood

Marvcus Patton had no idea how proud his father might have been, the day UCLA’s football program accepted him as a relatively undersized walk-on linebacker in the fall of 1985.

It was his dad who gave him the name Marvcus, with the extra “v.” Pronounced MARV-cuss, in honor of the Roman emperor and warrior Marcus Aurelius. Marcus comes from the name Mars, the god of war.

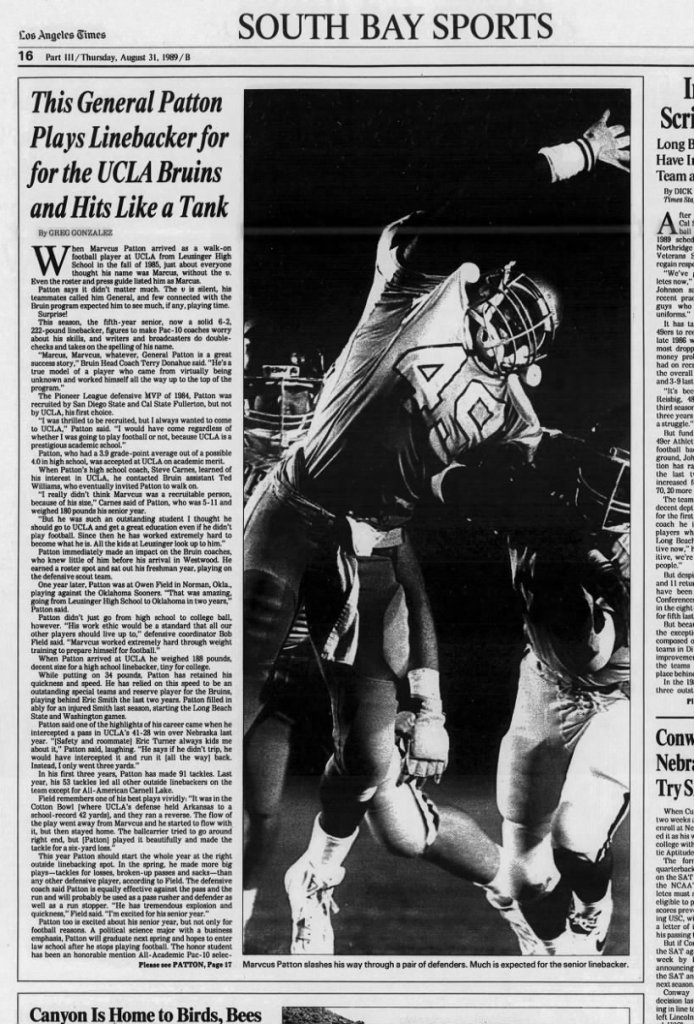

“As it turns out, he turned into a warrior on the football field,” his mother, Barbara, told the Los Angeles Times in a 1989 story as her son was about to enter his final collegiate season.

As it also turns out, Barbara was far more influential in Marvcus’ ascent into a football life.

Marvcus’ father, Raymond Hicks, never saw him play. Hicks was a Los Angeles Police undercover detective shot and killed in the line of duty during a drug bust when Marvcus was 9. Hicks had been separated from Barbara for some time at that point, eventually remarried and started another family.

Barbara was a single mom of two children, working as a PBX operation for the federal government’s General Services Administration in L.A. That was her Monday-to-Friday job. On weeknights and on Saturdays, she slugged it out as a linebacker for the Los Angeles Dandelions of the National Women’s Football League.

No flag-grabbing here. Helmets, shoulder pads, extra-thick padding up front. Full on contact. For $25 a day, which sometimes happened, sometimes not.

Like mother, like son. Kind of.

“I thought it was really cool to tell my friends that my mom was a linebacker,” Marvus Patton once shared. “My mom’s love for the game definitely influenced me. I always watched football on television and collected football cards, but seeing my mom play really made me want to be in the NFL.”

The son’s story

As the Pioneer League defensive MVP at Leuzinger High in Lawndale in 1984, Patton had only one college scholarship offer, from San Diego State. Cal State Fullerton was interested, but it couldn’t commit too much. It didn’t matter. Patton’s first choice was UCLA.

At 5-foot-11 and 133 pounds as a high school junior, he got up to 165 as a senior as he hit the weight room. But college choices were were limited. Academics mattered.

“I would have come regardless of whether I was going to play football or not, because UCLA is a prestigious academic school,” said Patton, who had a 3.9 grade-point average and made it into on scholastic merit. At Leuzinger, he had already completed upper-division classes as a freshman and sophomore and was practically able to graduate before his senior season.

Steve Carnes, Patton’s coach at Leuzinger, connected him with UCLA assistant Ted Williams. Patton was invited to walk on.

“I really didn’t think Marvcus was recruitable,” Carnes said. “But he was such an outstanding student I thought he should go to UCLA and get a great education even if he didn’t play football. Since then he has worked extremely hard to become what he is. All the kids at Leuzinger look up to him.”

After participating on the freshman scout team, Patton made it into the Bruins’ lineup by his sophomore year. He had put on more than 30 pounds but maintained his speed that set him apart on special teams.

Patton said a career highlight was intercepting a pass in UCLA’s 41-28 win over Nebraska in 1988.

By the time Patton hit his fifth-year senior season, at 6-foot-2 and 222 pounds, teammates nicknamed him “General.” Maybe because they couldn’t get past the Marcus-Marvcus hurdle.

“Marcus, Marvcus, whatever, General Patton is a great success story,” UCLA head coach Terry Donahue would say. “He’s a true model of a player who came from virtually being unknown and worked himself all the way up to the top of the program.”

Marc Dellins, the longtime UCLA senior associate athletic director heading the sports information office, recalled the time when the Bruins played in the 1989 Cotton Bowl at the end of Patton’s junior season. All the players received bolo ties with a plastic replica of the bowl logo. The name spelled on Patton’s tie was “Marvcus,” and Dellins, notcing it, said he could get that fixed and have his name spelled right.

“That’s when he tells me it was spelled correctly,” said Dellins. “I realized for almost two seasons we had been spelling it wrong. I asked him why he didn’t say anything, and he said he didn’t want to make a big deal out of it. I said: ‘That’s your name, you can make a big deal out of it’.”

Actually, when his mother every got annoyed with him, she said she she might call him “MAR-cus.” Normally, it was “Marc.”

During Patton’s senior season, as UCLA stumbled to a 3-7-1 record in 1989 (next-to-last in the Pac-10 and the Bruins’ worst performance in 10 seasons), Donahue noted that Patton “played with great heart and competitiveness. He’s really had a good year despite the fact the team has not. I certainly think on a different team and a different set of circumstances, he’d really receive a tremendous amount of recognition and notoriety for his play.”

Patton set a school record with 22 tackles behind the line of scrimmage. He was third in the Pac-10 in sacks with 11. Teammates named him the co-MVP to go with his political science degree on his resume.

Patton fell to the eighth round of the 1990 NFL draft before Buffalo took a chance on him with the 208th pick overall. Patton said he felt like he was a walk-on all over again.

“When you have that feeling that everyone’s against you and they don’t think you can get it done, it gives you a little extra drive,” Patton said. “I’ve always felt that I had to prove myself.”

Patton not only earned a earned a roster spot but played in all 16 games, then suffered a broken leg on the opening kickoff of the AFC Divisional playoff game against Miami.

A full-time starter by his fourth season as a left inside linebacker, Patton had five seasons in Buffalo, including Super Bowl trips in four straight seasons. Patton got to return to the Rose Bowl as a professional when the Bills played in the Super Bowl XXVII against Dallas and former UCLA teammate Troy Aikman in 1993.

Traded to Washington and moving to middle linebacker, he led the team in tackles three times. He had a career best 143 with 115 solo tackles in 1998. After a Redskins’ 14-point loss to Tampa Bay in 1996, Patton was quoted as saying: “We played like babies. We didn’t tackle. We didn’t chase down people. We let it slip away.”

His final four seasons were in Kansas City, named a team MVP in his first season when he had 135 tackles, after landing a six-year contract said to be worth $10.1 million.

Having an NFL career that spanned 204 games over 13 seasons, Patton never missed a regular season game. Only one other defensive player picked in that 1990 NFL draft — Hall of Famer Junior Seau out of USC, No. 5 overall — played more than the 208 NFL games that Patton did in their career.

At age 35 in his final season with the Chiefs, Patton had two interceptions (giving him 17 for his career) and two fumble recoveries (giving him 12). His scored his only NFL touchdown on a 24-yard interception return in 2000.

He was walking away from pro football right about the same age as his mom did back in her playing days.

The mom’s story

Running back is where Barbara Patton always thought Marvcus would shine in Pop Warner football.

“You’ve got the speed, the moves … running back is the right place for you son,” she would say.

“No, mom,” Marvcus would answer. “I want to play defense … just like you.”

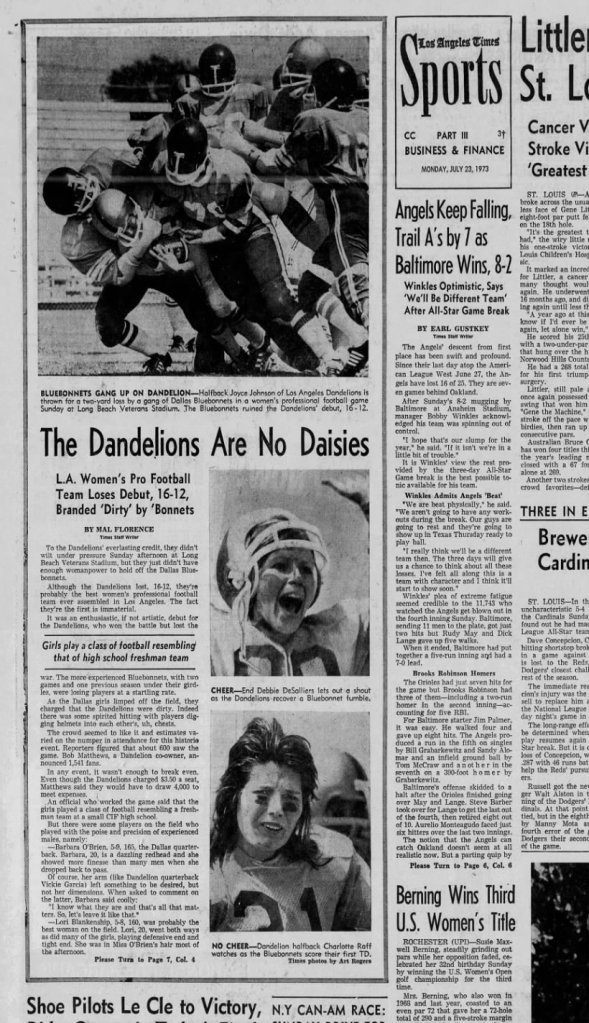

Barbara Patton knew what she was talking about. As 5-foot-4, 130-pound outside linebacker for the women’s professional Los Angeles Dandelions, starting with their debut season in 1973 and going until 1976, she was no shrinking violet. She was a dandy role model.

“I was so little that I don’t remember much about her playing,” Marvcus would say. “All I remember is that she was always really excited on game day.”

“I could fly,” she said, “and I could hit.”

Marvcus was 7 when he posed with his 11-year-old sister Debbie for a feature story on the life of a 32-year-old single working mom living in Inglewood who had this weekend hobby of trying to get her aggressive athletic nature out.

The story goes that Barbara heard about the Dandelions tryouts on the radio and talked her two sisters into joining her among the 350 candidates. Barbara was one of the 30 who made the cut.

“It was too rough for them,” she said of her sisters.

The story mentioned how Marvcus “waits on the sidelines” watching her practice. Barbara’s mother watched the kids as Barbara practiced at Fairfax High and played home games at Long Beach Veterans Stadium, Santa Monica College or East L.A. College.

In one game where the Dandelions played in San Diego, Barbara said she a receiver so hard, “it split her helmet. It kind of shook me up a little bit, too.”

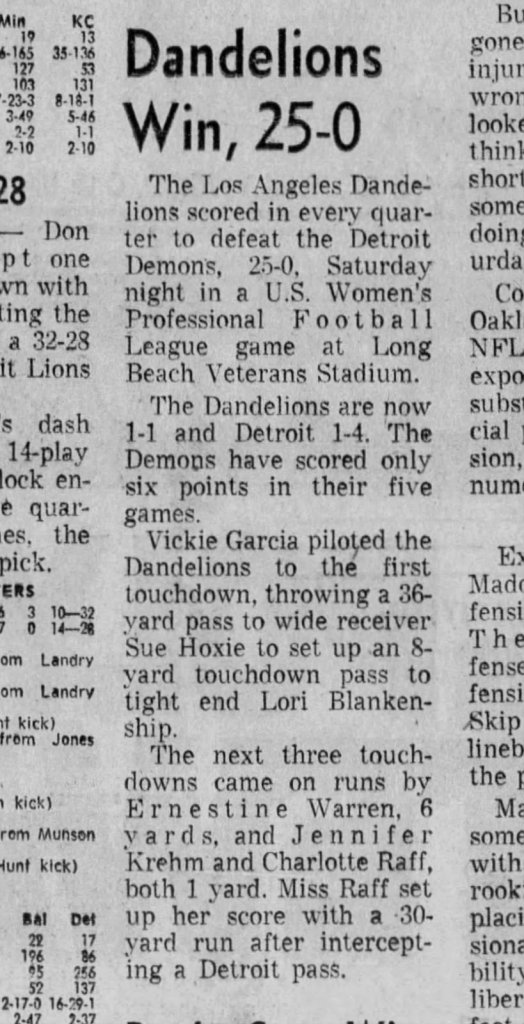

An Aug. 19, 1973 account of the Dandelions’ 25-0 win in Long Beach over Detroit noted that “the stellar defensive play by the Lion front four of Pam Brown, Barbara Patton, Sue Waldron and Janet Graffley stopped any offensive threat.”

Marvcus Patton said over the years he admired how Barbara was really both a mother and a father to him.

Even as his parents separated when he was very young, but his dad still kept in touch.

In August of 1976, Raymond Hicks, a 12-year veteran of the LAPD undercover narcotics unit working in the Venice division, died in the line of duty during a raid in Inglewood. Hicks was 35. A three-year Army veteran, Hicks received 21 departmental and citizen commendations during his career.

“I didn’t want to believe it at first,” Marvcus said of his father’s death. “I just kept thinking he would walk through that door. But as time went on I realized I had to accept things as they were. The thing I’ll always remember is that my dad was killed while trying to do the best job he could.”

Raymon Hicks’ death meant Marvcus’ education would be paid for by the Los Angeles Police Memorial Foundation. That included his admission to UCLA.

“I grew up without a father and we all hear the stories about your chances in that situation,” said Patton, whose middle name is Raymond. “But I went to school and succeeded academically and that allowed me to play sports. Had I not gone to school and done well, I would have never gotten into UCLA. I never would have been playing football there. I use that as an example with kids. If you go to school, it opens up a lot of possibilities that you might otherwise not have.”

Before the 1993 Super Bowl, Los Angeles Daily News reporter Eric Noland talked to Patton about his father, who, at the time of his death he was initiating going to law school.

“Honestly, you don’t really realize he’s a police officer, and how dangerous it is at the time,” Marvcus said. “As you get older, yeah. But 9 years old . . . and nothing had happened to make you aware of the dangers. I’m sure he would be proud of both – what I did when I was going to school . . . also what I’m doing now. I’m sure he would be very proud of everything I’ve done so far.”

Noland later spoke with Lt. Don Kitchen, a watch commander in the West Valley who had been Hicks’ partner for two years, and Det. Dave Harrison., working with Hicks in the Venice Division narcotics unit the night he was killed.

Harrison and Kitchen are white. At Hicks’ funeral, a reporter approached Kitchen and asked about Hicks being one of the few black LAPD officers killed in the line of duty.

Kitchen: “I turned and said, ‘He wasn’t black. He was blue (the uniform). He was my partner.’ “

“What I remember most about Ray,” Harrison says, “is he never had a bad word to say about anybody. He never swore. He treated people with respect. He was the ideal policeman.”

“I’ll tell you something unbelievable,” Kitchen said. “Ray had an informant, who happened to be living with one of my informants. A couple of heroin addicts. After he was killed, they called me and said how terrible it was. ‘He always treated us fair. Can we come to the funeral? We know we’re just junkies and everything, but we want to come.’

“I had never heard of that before – snitches that a guy had put away (in jail) wanting to go to the funeral. But they came.”

Marvcus said what got him through that trauma was his mother “is a very strong person. And I have a large surrounding family, extended relatives. We all stuck together. That helped me as a youngster, as well as the rest of the family, get over it.”

Marvcus added that Barbara was “my biggest fan and my biggest critic. No matter what I’ve done she’s always been behind me and tried to help me in every way possible. When it comes to football, she really knows her stuff. It’s like having another coach.”

Barbara would remind Marvcus not to tackle with his arms, read the quarterback’s eyes … all the coach-speak she could remember from playing.

“I’ll say, ‘Remember Marvcus, football is just like you’re in a war zone, you’re protecting your territory’,” said Barbara. “Sometimes he tells me, ‘Yeah, yeah, I know, mom. I’m a pro football player.’ I say, ‘Don’t forget, I was one too’.”

The Dandelions, led by quarterback Jennifer Krehm, were the best known of all the women’s pro teams in Southern California history. Their rivals were the California Mustangs, based in the San Gabriel Valley from 1974 to ’76, which played at Citrus College in Glendora and practiced at La Salle High in Pasadena. The Pasadena Roses played at Azuza College and their best known player was Naomi Malauulu, a quarterback/punter.

The Los Angeles Scandals came up in the mid-1980s as part of a revival of the pro league, playing games at L.A. Valley College in Van Nuys.

In the 2021 book, “Hail Mary: The Rise and Fall of the National Women’s Football League,” co-author Lyndsey D’Arcangelo explained in an interview: “The whole thought behind it was to create something like the Harlem Globetrotters, where they would travel as a troupe to different cities around the Rust Belt area and compete against men’s teams. From there, what he realized was that the women could actually play, and play well. Just think of this melting pot of women who had this one singular goal: to get the opportunity to play football, and they took it.”

Barbara Patton’s participation in the Los Angeles’ women’s football scene was an extension of what had been doing on decades earlier, just hardly noticed.

As is noted in the “Hail Mary” book, De La Cretaz and D’Arcangelo wrote that “history was made” in October of 1939 when the first full-contact women’s football game was played at Gilmore Stadium in Los Angeles. The Chet Relph Hollywood Stars lost to the Marshall Clampett Amazons of Los Angeles, 12-6, in front of 2,500.

This was a point in time when UCLA’s Jack Robinson had been making a name for himself as a football star in the city.

This event, almost a decade before the NFL’s Rams moved to Los Angeles, used NFL rules and played four 12-minute quarters. Life Magazine and the Los Angeles Times covered it.

The book says players wore “regulation uniforms” with tennis shoes and an “undersized football.” Shirley Payne’s 45-yard interception return helped seal the win.

Life magazine noted: “It was no powder-puff battle. The girls were rough and tough. They kicked each other in the stomach, dirtied each other’s faces, tackled and blocked savagely, knocked four girls unconscious. And strangely enough they played good football, seldom fumbling or running away from their interference.”

A two-paragraph story in the Los Angeles Evening Citizen made note that it was actually a women’s softball team recruited to play football that comprised the squad:

The book “Hail Mary” makes note that Los Angeles Times columnist Dick Hyland was far more condescending in the days leading up to it — failing to cover it at all — and wrote a week before the event: “I don’t know what all this femine activity is supposed to prove in the world of sports. In fact, I’m wondering if the report doesn’t belong in the entertainment pages or over with the crime news.”

Women’s football came into its newest cycle of interest in the late ’60s with the Women’s Professional Football League. It expanded in 1971 past its first four teams, including a Los Angeles franchise in its Western Division. By 1973, the league disbanded and would come back with the game name from 1999 to 2007.

The National Women’s Football League emerged from 1974 to 1988, provided the great opportunity. The Los Angeles Dandelions, which launched in 1973, were a founding member of the new NWFL along with the California Mustangs and, eventually, the Pasadena Roses.

In 2023, two documentaries about the league appeared.

“We Are The Troopers” focused on the Toledo Troopers of the WPFL and the seven titles the team won between that league and the National Women’s Football League. “The Herricanes” doc allowed filmmaker Olivia Kuan shine a light on the league’s existence — which included her mother, Basia, playing for the Houston Herricanes.

And about that $25 a game? The documentary shed more light on that.

“Most have reported that never actually happened,” Kuan said about the payments. “It took everything they had just to keep the teams afloat. The players were dedicated to the sprot and their teammates without financial incentives. They did it for love of the game and for the many ways they grew as individuals.”

When reminded that her son’s signing bonus as an NFL player was $2 million after he went from Buffalo to Washington, in addition to his $6.8 million, four-deal deal that had a base salary of $900,000, compared to what she had made as a pro player, Barbara added: “That’s why I want to come back in my next life as a man.”

Thanks to the Women’s Football Alliance, a semi-pro summer-based league that started in 2009, there is place for the next generation of female football players. It once held its 2015 title game at L.A. Southwest College, and had at one time more than 60 teams.

The Los Angeles Warriors were part of the evolution of a Southern California franchise in the league from 2017 to ‘18 that started as the California Lynx, went to the Pacific Warriors and, as of 2024, were the Cali War, playing home games at Mira Costa High in Manhattan Beach. The team also had played home games at the Michelle and Barack Obama Sports Complex (formerly known as the Rancho Cienega Rec Center near Dorsey High School).

In 2022, the Los Angeles Legends appeared, part of the Women’s National Football Conference and playing games at Serra High in Gardena from April to May with a girls’ and women’s flag squad as well as a tackle football roster.

We are also tempted to overlook the Los Angeles Temptations, but since you asked …

Created for something called the Legends Football League based on Ontario, the Temptations were one of two teams that debuted at halftime of Super Bowl XXXVIII in 2004 for the Lingerie Bowl. Models and actresses wearing lingerie with minimal gear, Playboy Playmate Nikki Ziering was the leading known player for Team Dream, the year before it officially became the Los Angeles Temptations for Lingerie Bowl II.

“What playing surface does the Lingerie Bowl use?” asked ESPN’s Jim Capel. “Natural grass, artificial turf or Jell-o? … And most importantly, should we refer to this as Lingerie Bowl I, Lingerie Bowl 2004 or Lingerie Bowl 38C?”

By 2009 and ’10, the Lingerie Football League had an indoor season (at the L.A. Sports Arena, before moving to Citizens Bank Arena in Ontario) and an outdoor season (at the L.A. Coliseum). The league rebranded, moved around and somehow a team called the Los Angeles Black Storm emerged in something called the Extreme League, (aka, X League), billing itself as “a new era in women’s empowerment” with a 7-on-7 format on a 70-yard field.

“The X League will also be established as the highest echelon of women’s tackle football,” it boasted.

Again, in the book “Hail Mary,” the topic is brought up: If the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y. can dedicate space to the All-American Women’s Professional Baseball League of the 1940s, why can’t the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio acknowledge some history of the National Women’s Football League?

The book points out that Marvcus Patton did an interview in the early 1990s while in Buffalo talking about his mother: “I’m definitely proud of my mother, just for the fact that she played and allowed me to play.”

The book’s authors write on page 243:

“Though Marvcus never made it to the Pro Football Hall of Fame, perhaps his mother still has a chance. The lack of recognition of the NWFL raises a legitimate question about the women who played. They are a significant part of football history … and should be honored as such … Imagine a display featuring pictures, memorabilia and information about NWLF teams and players that would serve as a reminder to football fans young and old that the NWFL existed, and a tribute to all the women who played so that their stories live on and are not overlooked and forgotten.

“Imagine what a moment it would be for (Barbara) Patton and Marvcus to witness together?”

Who else wore No. 49 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

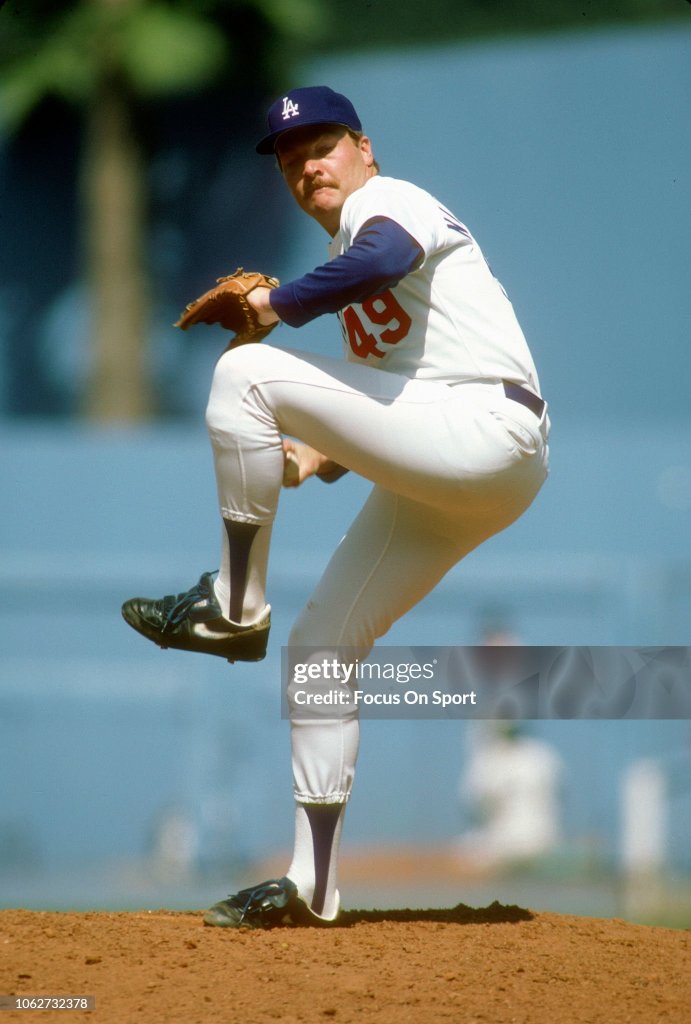

Charlie Hough, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1970 to 1980):

Best known: As he tried to master the knuckleball in 401 games for the Dodgers over 11 years, Hough would finish off 222 games and log 60 saves, including 18 and 21 for the Dodgers in their NL pennant winnings teams of 1976 and ’77. Converted into a starter at age 31 in 1979, the Dodgers were still trying to figure out what to do with him by the time they released him. A first baseman and third baseman at the Dodgers’ Single-A Ogden team under manager Tommy Lasorda in 1966, Hough was “the only guy I knew who could get into a race with a pregnant woman and finish third,” was playing first base, third base … and pitching, and I had to decide where he should play,” said Lasorda. “As soon as I saw him, I knew he’d have to pitch.” As Hough’s arm grew weary, minor league coach Goldie Holt asked him to try the knuckleball. “It was a fluke,” Hough would say. He huffed and puffed and floated this pitch to the plate, mastering it under the tutelage of 48-year-old future Hall of Famer Hoyt Wilhelm. Hough started his career wearing No. 31 in 1970 but switched to No. 49 honor Wilhelm, continuing a trend for those pitchers who committed to the knuckleball pitch, including Dodgers pitcher Tom Candioitti (1992 to 1997).

Not well known: The 13 MLB seasons Hough logged after he left the Dodgers were all as a starter, twice leading the league in games started and complete games. He was purchased Texas in July of 1980 and started 313 games for the Rangers over 11 seasons, plus 56 for the Chicago White Sox and 55 for Florida before he retired at age 48, amazing 107 complete games. He was the very first pitcher in Marlins history when the team made its 1993 debut — and recorded a 6-3 win over the Dodgers in Miami against Orel Hershiser.

Tom Niedenfuer, Los Angeles Dodgers relief pitcher (1981 to 1987):

Best known: Game 5 of the 1985 National League Championship Series ended when Niedenfuer’s first pitch to Ozzie Smith was lined over the right field wall at Busch Stadium in St. Louis. Two days later, Jack Clark crushed a Niedenfuer offering into the left-field pavilion at Dodger Stadium for a three-run, ninth-inning home run to erase a 5-4 deficit in Game 6, effectively ending the Dodgers’ season. “What can you do?”Niedenfuer said in a 2010 Los Angeles Times story. “It happened.” Two innings earlier, Niedenfuer struck out Clark on a fastball out of the strike zone after setting him up with several sliders. During the regular season, Niedenfuer had a career highs of 19 saves and 106 1/3 innings.

Not well known: Niedenfuer was nicknamed “Buffalo” because of the 7 1/2 size of the cap he wore.

Dennis Smith, USC football defensive back (1977 to 1980):

Best known: Pulling in 15 interceptions in his 45 games over four years at USC, Smith was part of two Rose Bowl teams and on the ’78 national championship team. Smith was All-Pac-10 for three seasons and the No. 15 overall pick in the 1981 NFL draft by Denver.

Not well known: Smith was a wide receiver and defensive back out at Santa Monica High, where he was the CIF Southern Section co-Player of the Year in 1976.

Charles Phillips, USC football safety (1972 to 1974):

Best known: Out of Blair High in Pasadena, Phillips set an NCAA record with 302 interception return yards with seven picks as a senior, leading to an All-American status on the second of his two Trojans’ national championship teams. During USC’s historic 55-24 victory over Notre Dame in 1974, he returned one of his three interceptions 58 yards for one of two touchdowns, earning the Theodore Gabrielson Award as the most outstanding player in the rivalry game that season. A second-round pick of the Oakland Raiders, Phillips played in Super Bowl XI.

Not well known: Phillips plucked two fumbles out of the air and returned them both for touchdowns against Iowa in 1974, putting his name in the USC record book for return yardage in a game, with 181, and the highest average-gain-per-return, at 90.5.

Sedrick Ellis, USC football defensive lineman (2005 to 2007):

Best known: Ellis’ three-year career at USC produced 142 tackles (75 solo, 29 for losses) and 17.5 sacks in 36 games as well as the Morris Trophy for top lineman in the Pac-10. In USC’s win over Michigan in the 2007 Rose Bowl, Ellis had seven tackles, a sack and a pass deflection. During his senior year he was voted Pac-10 Conference Defensive Player of the Year and was first-team All-American. New Orleans made Ellis the No. 7 overall pick in the 2008 NFL draft.

Not well known: Ellis came out of a Chino High program that won CIF titles in 2000 and ’01.

Carson Schwesinger, UCLA football linebacker (2021 to 2024):

Best known: From Oaks Christian High in Thousand Oaks, Schweisinger made it on the UCLA roster as a walk on. By the time he earned a scholarship and made it through his junior season, Schwesinger was a first-team All-Big Ten pick, a Bruins team captain, a finalist for the Butkus Award (top linebacker in the nation) and considered for the Burlsworth Trophy (top walk-on). Teammate Bryan Addison called him “Captain America.” All of this happened as he pursued a bio engineering major.

Not well known: After leading the nation in solo tackles with 90 and finishing third in all of college football in total tackles with a Big Ten best of 136, Schwesinger was the 33rd overall pick of the 2025 draft by the Cleveland Browns — the first player from UCLA or USC selected in the NFL draft.

We also have:

Tuli Tuipulotu, USC defensive lineman (2020 to 2022)

Tim Belcher, Los Angeles Dodgers (1987 to 1991)

Blake Treinen, Los Angeles Dodgers relief pitcher (2020 to present)

Rod Perry, Los Angeles Rams (1975 to 1982)

Jack Sanford, California Angels pitcher (1965 to 1967)

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 49: Marvcus Patton (and his mother, Barbara)”