This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 45:

= A.C. Green, Los Angeles Lakers

= Pedro Martinez, Los Angeles Dodgers

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 45:

= Henry Bibby, UCLA basketball

= Andre McCarter, UCLA basketball

= Tyler Skaggs, Los Angeles Angels

= Noelle Quinn, UCLA women’s basketball

= Jim McGlothlin, California Angels pitcher

The most interesting story for No. 45:

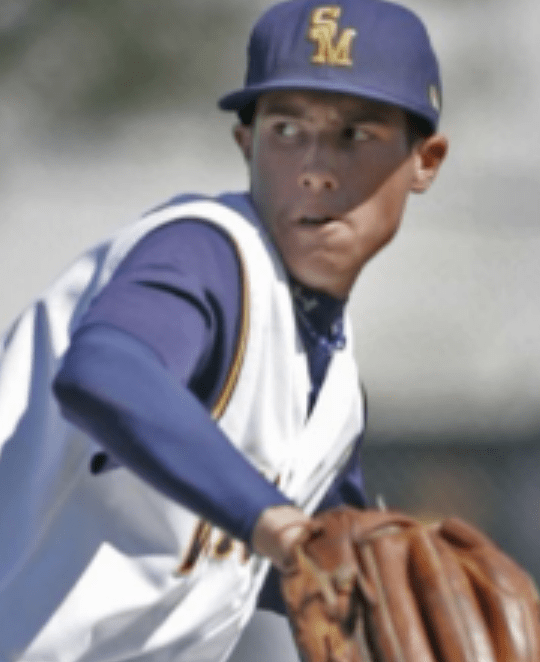

Tyler Skaggs, Los Angeles Angels pitcher (2014 to 2019) via Santa Monica High

Southern California map pinpoints:

Woodland Hills, Santa Monica, Anaheim

The jerseys became a stack of 45s. The Angel Stadium pitcher’s mound turned into an enormous turntable.

The sound of silence was painful.

One by one, the Los Angeles Angels’ players wearing special Tyler Skaggs tribute jerseys during a 13-0 win on July 12, 2019 against the Seattle Mariners took them off and laid them on the dirt, surrounding a large “45” already been painted behind the pitching rubber.

This was a place Skaggs started every time it was his turn in the rotation for the previous five seasons. A place where, a few hours earlier, his mother, wearing her own Skaggs 45 jersey, threw a perfect strike in a first-pitch ceremony amidst tears.

The fact that on this night, Angels pitchers Taylor Cole and Felix Pena combined on an improbable no-hit performance against the Mainers, and close Skaggs friend Mike Trout drove in six runs with a homer and two doubles, only amplified the emotions.

What was otherwise a time to celebrate tapped into deeper emotional pain.

It was the Angels’ first game in five days. They finished a road trip in Texas and Houston that ended abruptly, and that created a longer time span including the All-Star game.

The game scheduled for July 1 in Arlington, Tex., had been postponed. Earlier that afternoon, Skaggs was found dead in his hotel room. The cause was determined to be directly related to a reliance on opioids, attacking the pain that had been ongoing from an injury recovery but also becoming predictably addictive.

Consuming a mix of alcohol, oxycodone and fentanyl ended Skaggs’ life just a few weeks before his 28th birthday.

This mound of jerseys would have to be disassembled — there was a game to play the next night — but the impromptu gesture, inside the stadium and at another mound outside the main entrance amidst stuff Rally Monkeys, flower arrangements and hand-made cards from fans, had served its purpose.

The Angels had been through this kind of mourning process before related to the sudden tragic death of players — Lyman Bostock, Nick Adenhart, Donnie Moore, Mike Miley — yet there was nothing different about Skaggs’ passing. It was a reminder about a bigger issue in society that had been taking down too many people far too early.

The background

Growing up in Santa Monica, Tyler Skaggs was already into full T-ball mode at age 5 after trying to play basketball, football and soccer. By the seventh grade, he was already throwing in the mid- to-upper 80s fastball.

His mom, Debbie Hetman, knew the power of sports. She was a Cal State Northridge athlete and a longtime softball and volleyball coach at Santa Monica High, later a valued phys ed teacher when her son started attending. Hetman’s twin sister coached as well at various Southern California high schools.

“If you grew up in Santa Monica, you knew who my mom is,” Skaggs said.

“She is really hard on me,” Skaggs expanded in an L.A. Times interview during his junior season. “Even now she said I should be getting straight A’s. She makes me do my curveball drill. She says, ‘Go run around the block until you get tired’.”

Skaggs would reach 6-foot-4 and 220 pounds. The kid born in Woodland Hills would look very much like his father, Darrell, former standout shortstop at Canoga Park High.

Skaggs was recruited by Cal State Fullerton, UC Irvine, Arizona and UCLA by the time he was named Ocean League Player of the Year at Samohi with a 1.11 ERA, striking out 89 in 63 1/3 innings. In the regular-season finale during his junior year against Culver City, Skaggs had a perfect game for 6 2/3 innings until giving up a two-strike single. He ended up throwing a one-hitter over 10 innings, striking out 14 and surrendering no walks in a 2-0 win.

The year, before as a sophomore, Skaggs got to pitch at Dodger Stadium. Santa Monica High made it to the CIF-Southern Section Division IV final against Charter Oak of Covina and lost, 7-1, with Skaggs pitching the first four innings.

As a senior, Skaggs had an ankle injury that sidelined him for several weeks. As the MLB draft approached, a scouting report in the L.A. Times noted “his velocity was inconsistent, but at his best, Skaggs left little doubt his fastball and curveball were worthy of first-round consideration.”

The Angels, the team Skaggs said he followed most growing up, had four picks in the first round of the 2009 June draft. High school outfielders Randal Grichuk and Mike Trout were their 24th and 25th overall picks. Skaggs was still available as the 40th overall choice. Future starting pitcher/teammate Garrett Richards went two spots behind him. The Angels had the extra pick for Skaggs in the supplemental phase as compensation for losing Mark Teixera in the free agent market. Skaggs was the 19th pitcher taken during the first 40 choices, starting off with Washington’s No. 1 overall pick Stephen Strasburg.

Skaggs and Richards would help re-set the foundation of the Angels’ rotation as the team was still reeling from the automobile death just months earlier of pitcher Nick Adenhart, who was 22.

Skaggs modeled himself after Angels star left-hander Chuck Finley, and outfielder Tim Salmon was his favorite player. He remembered as an 11-year old joining his step-brother attending Game 6 of the 2002 World Series at Angel Stadium, the come-back win over San Francisco that forced a fateful Game 7.

Signing a $1 million bonus, Skaggs joined Trout as his minor-league roommate on the team’s Single-A team in Cedar Rapids during the 2010 season.

Skaggs also made good on a promise: He told his mom’s Samohi softball team that if it won the CIF title in 2010, he would buy them all championship rings. They won it, and he did it.

Just a season-and-a-half into his minor league career, Skaggs, who posted an 8-4 mark with a 3.61 ERA in 14 starts at Cedar Rapids in 2010, was sent to Arizona as the “player to be named later” as part of a package deal the Angels needed to finish off after obtaining veteran All Star starter Dan Haren from the Diamondbacks at the trade deadline.

At age 20, Skaggs was promoted to the Diamondbacks’ Double-A Mobile team where he helped it win the Southern League title. In 2011, he was also on the U.S. team for Futures Game at Chase Field in Phoenix during the MLB All-Star break.

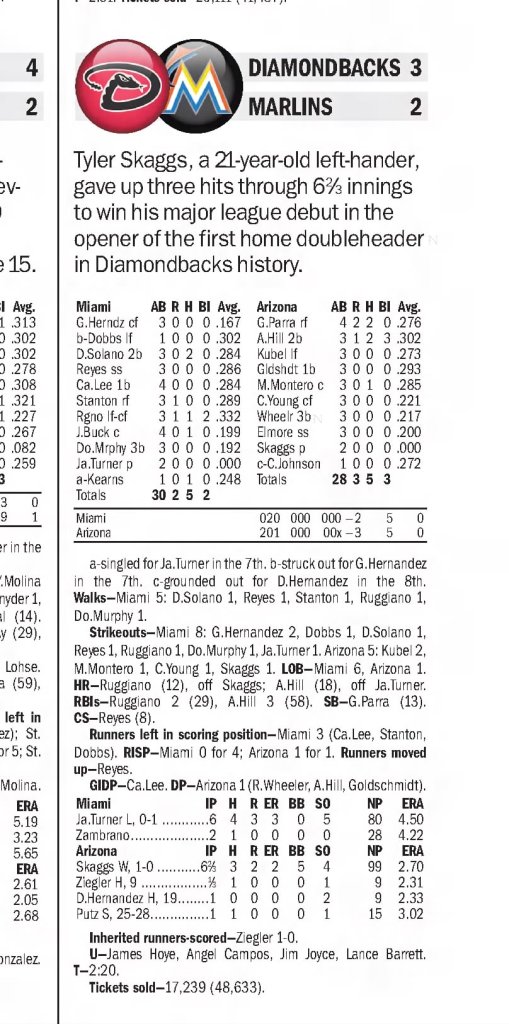

Making his major league debut as a 21-year-old late in the 2012 season, Skaggs held his own. He was back again with the big-leagues at the end of 2013.

But as he developed in the Diamondbacks system, he remained on the Angels’ radar. Or more specifically, on Jerry Dipoto’s talent charts.

Dipoto was the Arizona interim GM who dealt Haren to the Angels in 2010 and got Skaggs among the three young arms from the Angels’ farm system in exchange. Now as the Angels full-time GM, Dipoto maneuvered a three-team trade that brought Skaggs back to Anaheim at the expense of outfielder Mark Trumbo.

“The ups and downs of last year made me a stronger pitcher and a stronger competitor,” Skaggs said. “You learn a lot more from failing than winning.”

Skaggs impressed Dipoto with his 94-mph fastball, tight curve and change up.

“Tyler has the weapons, the belief in himself,” said Dipoto during 2014 spring training. “The belief of the coaching staff, and the front office. I think he’s pitching with that confidence.”

Skaggs would add: “It feels good (to be in the organization) especially when the most important guy in the organization trades for you twice. It’s a great opportunity. It’s a special thing. It feels like I’m part of family here.”

In May of ’14, Skaggs was the first Angels starting pitcher to work his way into the ninth inning of a game, a 5-3 win at Toronto, where he retired 21 straight batters after giving up an unearned run in the first inning.

As he was making his 18th start with the Angels in 2014 — posting a 5-5 mark with a 4.30 ERA — Skaggs was working on a no-hitter going in Baltimore. There was one out to go in the fifth inning during that scoreless game on July 31, as he struck out seven with two walks.

Skaggs’ elbow flared up. He had to come out. Originally diagnosed as a flexor strain, it was discovered to be a partial tear of his ulnar collateral ligament. Two weeks after it happened, Skaggs opted for Tommy John surgery for his left elbow.

“It’s a hard day but only a small bump in the road #2016” wrote Skaggs in a tweet.

“I’m still kind of dumbfounded on how it happened,” Skaggs later explained. “It’s hard to go from throwing 95 to 87; or giving up no hits, thinking it’s turning into something special, and then all of a sudden you throw one pitch and you can’t feel your hand. I felt in my heart, in my gut, that I needed to get this (surgery) done so I could be 100 percent out there and not look back over my shoulder and think, ‘Should I let this one go or lob it up there and see how it feels?'”

Angels manager Mike Scioscia added: “He’s very disappointed, but as he began to understand the situation, he definitely came to grips with it.”

Skaggs missed all of 2015 and it was nearly two years later when he returned, on July 26, 2016, throwing seven shutout innings in a win at Kansas City with five strikeouts and one walk. That season, as the Angels couldn’t get over the .500 mark, Skaggs made it through 10 starts, went 3-4 and posted a 4.17 ERA, showing some fatigue in the middle of September.

Notably, Skaggs’ elbow pain, and more injuries that came up as he was trying to work around it, continued.

In 2017, Skaggs got through April but then had to sit three months with nagging ailments. He came back in August, limping to a 2-5 mark and 4.55 ERA in 16 starts, three of them going seven innings (where he picked up the two wins). His most disappointing start was lasting just two innings at Texas on Sept. 1, giving up six runs and walking three while striking out just one.

During the 2018 season, after Skaggs won an arbitration case and saw his salary bumped to $1.9 million after years of having to accept the minimum of $500,000, he make a career-high 24 starts, starting off with the second game of the season at Oakland where he polished off the Athletics with a 2-1 win, pitching 6 1/3 shutout innings.

Skaggs drew consideration for the AL All Star team that summer, but he aggravated a hamstring injury in early July. On the last day of the month, he gave up 10 runs over 3 1/3 innings to Tampa Bay, again complaining of the hamstring issue. Angels general manager Billy Eppler decided Skaggs needed to shut it down again.

Skaggs’ ’18 season included three trips to the injury list to get to an 8-10 mark with a 4.02 ERA, as he struck out 129 in 125 1/3 innings but also gave up 127 hits and 14 homers. He made only one start in August and never went more than 3 1/3 innings in his last four appearances, losing twice.

Still, Skaggs received a new $3.7 million deal for 2019. He was the fourth man in the rotation behind Trevor Cahill, newcomer and former Mets Cy Young winner Matt Harvey and Felix Pena.

Skaggs posted three wins in a row from June 13-23 in games at Tampa, Toronto and St. Louis. On July 29, Skaggs gave up two runs in 4 1/3 innings against Oakland at Angel Stadium, walked four and struck out five, but the Angels lost 4-0. Oakland had shut down the heart of the Angels lineup that day with Mike Trout, Shohei Ohtani and Albert Pujols. The Angels dropped to 42-42 in the AL West.

To that point, Skaggs posted a team-best seven wins (against seven losses) in 15 starts over 79 2/3 innings, striking out 78 to go with a 4.29 ERA.

Reams of federal court documents would eventually produce detailed information and a road map to what happened to Skaggs in the aftermath of a six-game road trip he and his teammates embarked on at the end of June, leaving Long Beach Airport to Arlington, Tex.

It was said that Skaggs seemed to be in good spirits, dressed in a black cowboy had with bolo tie and boots. He talked teammates into dressing up with Western gear for the journey to Texas.

Skaggs also sent text messages to Eric Kay, the Angels’ communications director, asking if he could find him some “blue boys” — oxycodone pills — and gave him his hotel room number in Arlington, Tex.

When teammates and his wife, Carli, saw text messages to Skaggs went unanswered on early Monday morning, teammate Andrew Heaney knocked on Skaggs hotel room door to try to get him to go to lunch. No response that afternoon.

Angels traveling secretary Tom Taylor is asked to do a welfare check on Skaggs, getting the team’s security lead, Chuck Knight, to get into the room. Knight called 911, medics respond, and it was reported they did not even try to use naloxone, the drug that reverses the effects of opioid, because “the patient had signs incompatible with life, unable to be revived.”

As the news got out, Angels manager Brad Ausmus pulled the team together, they switched hotels when an investigation began, and that night’s game against the Rangers was called off.

Skaggs’ family flew to Texas. An autopsy began the next day that would eventually rule out suicide or foul play. It didn’t come until a month later that the coroner determined it to be a mix of alcohol, fentanyl and oxycodone intoxication.

The Angels played their game against Texas on July 2 and pulled off a 9-4 victory. All wore a black No. 45 patch on their jersey. The team finished two more in Texas and went to Houston. A 5-4 win in the series opener was the spot in the rotation where Skaggs would have been scheduled to pitch, against Justin Verlander. After losing the next two against the Astros, the Angels went back to Anaheim for a needed five-day break because of the MLB All Star game.

Trout, however, was obliged to go to Cleveland. He started for the AL, played center field and hit third. He’s also wore No. 45 in honor of Skaggs.

Dr. Ben Drati, Superintendent of the Santa Monica Malibu Unified School District, was one of many Southern California connections to Skaggs who felt this loss personally.

“Tyler continued to make visits to our schools the past several years to speak with students and we proudly watched his ascent in professional baseball, along with his family,” he said.

During the All-Star break, Daily Breeze columnist Mike Waldner tracked down Skaggs’ Santa Monica High coach Rob Duron to get his perspective. Duron said he had been so distraught he wouldn’t watch any of the TV reports about what happened.

Duron choose to remember how Skaggs was receptive to him imposing a pitch count on him to save his arm. It would have been easy to get caught up in the attention he attracted from scouts — Tommy Lasorda came to watch him one time. He remembered Skaggs as level headed and a clear thinker.

“Tyler had the heart of a lion,” Duron said. “He was a great kid who worked his tail off. There never were any rants from him. You did not have to worry about him. He did what was expected. If it was picking up the helmets after a game, he did it without complaining or expecting special treatment because he was the star all the scouts were coming to watch.

“It was a circus. College coaches were calling me all the time. I’d have him throw in the outfield before games so he could get away from everyone. We’d talk there where nobody could hear us. I told him, ‘This is your sanctuary.’

“He was a special athlete.”

To start the second half, the Angels created a banner honoring Skaggs on the center-field outfield wall, and they hung his No. 45 jersey in the dugout. They had Skaggs’ mother, Debbie, throw out the ceremonial first pitch. It is perfectly delivered, as her husband (and Tyler’s step-dad) Dan, and stepbrother Garrett, wearing Tyler’s No. 11 high school jersey, were on the infield.

Also there was Skaggs’ widow, Carli, who married him just the previous December.

The team wore the all-red-colored Angels tops with Skaggs name and number on them — that was Skaggs favorite version of the team jerseys, he had said. The “Calling All Angels” video montage started the game as it always had for the team’s home games, but this time it seemed more surreal, along with a long moment of silence.

Trout hit a two-run homer on the first pitch he saw in the bottom of the first, a 454-foot blast, part of a seven-run first inning that felt more cathartic than anything. The lead expanded to 9-0 after the third inning.

Relief pitcher Cole took the mound as the “starter,” and otherwise scheduled starter Pena came in for the final seven. Somehow, they pieced together the 13-0 victory with the first combined no-hitter thrown in California since July 13, 1991 — the day Skaggs was born.

On July 22, the Angels’ Monday off day, the team joined Skaggs family for a funeral at St. Monica Catholic Church in Santa Monica. Three busses brought Angels players to the Mass. Friends of Skaggs, including players Ryan Braun, Jack Flaherty and Trevor Plouffe, also attended. More than 900 were there. Teammate eaney was one of 14 who eulogized Skaggs.

After the two-hour service concluded, an In-N-Out catering truck was on site, serving double-doubles at the reception.

The Angels had two games next at Dodger Stadium against the Dodgers — a series Skaggs had been looking forward to as the rotation played out to where he would pitch. After beating the Dodgers twice, the Angels had won 12 of the 18 games since Skaggs’ death.

As the legal system took its course, Angels’ employee Kay was charged with the distribution of a controlled substance resulting in death. A lengthy trial started in February of 2022, and a jury found him guilty, with a sentencing of 22 years in federal prison to follow.

Federal prosecutors suggested Skaggs death, while ruled accidental, was the result of a culture in baseball of self-medicating to play through injuries.

In the February 2022 trial against Kay, Skaggs’ wife, mother and teammates talked about Skaggs’ history of drug abuse going back to 2013, focusing on the use of Percocet.

One of the teammates, Harvey, acknowledged while under immunity from criminal conviction to being a cocaine and oxycodone user and occasionally providing Skaggs with oxycodone pills when he played for the Angels in 2019. Harvey was eventually handed a 60-game suspension by MLB in May of 2022.

Harvey, on the injured list and not with the Angels on the road on July 1, 2019, said he threw away his remaining oxycodone pills when he found out Skaggs died because he “wanted absolutely nothing to do with that anymore.”

Asked if he ever warned Skaggs to be careful, Harvey said in court: “Looking back, I wish I had. In baseball, you do everything you can to stay on the field. At the time, I felt as a teammate I was just helping him get through whatever he needed to get through.”

Harvey, C.J. Cron, Cam Bedrosian, Mike Morin and Blake Parker were five former Angels players who admitted, under immunity, that they received opioids from Kay.

In June of 2024, Kay would tell the New York Times that his responsibility lied in not aiding in Skaggs’ sobriety. But he still refuses to believe he is responsible for his death.

“I feel horrible that I didn’t stop contributing to his addiction. He had so much more to live for than me,” Kay said. “I don’t mean that to sound trite. He did. He was just married, now he’s making millions of dollars. He’s basically a front-line starter.

“‘What are you doing?’ I should have said that. ‘Tyler, what are you doing, dude?’”

More documentation but not presented in the trial came out that as Skaggs tried to overcome a groin injury as well as a hamstring pull during the 2016 and ’18 seasons, his agent, Ryan Hamill, had kept advising him to play through the pain — which seemed disastrous in hindsight.

Afterward, the Skaggs family filed a wrongful death suit against the Angels, contending that it allowed Kay, who later admitted to his own drug issues, to work closely with players “at risk of turning to medication to assist with pain management.” The team denied knowing about Skaggs’ drug abuse problems.

The civil trial that started in October of 2025 eventually included debate, no matter how uncomfortable it became — about how valuable Skaggs was as a pitcher. Meaning, what could he have made in salary over the course of his career had he lived.

Skaggs’ family sought between $75 million and $118 million in damages, based on potential salary lost. The Angelus suggested the number started at $0 and may have went as high as $30 million based on free agency and arbitration, according to the New York Times coverage of the trial.

On top of emotional damages, Skaggs’ Baseball-Reference.com statistics were also introduced as a way to gauge his financial profile determining if he was the team’s ace based on the data, name recognition, reputation and comparable pitchers’ contracts.

Trout, again talking about his relationship with Skaggs for so many seasons, was one of the witnesses called to the stand. On the night that Skaggs died, Trout said he saw Skaggs drink a couple beers before the two rode up in the hotel elevator together. After hearing the following day about Skaggs’ death, Trout said he broke down crying. The following day, Trout said, Kay asked him to speak with the media about Skaggs.

“It’s sad losing somebody,” Trout said in court.

On the Friday before Christmas in ’25, as the jury had heard all the testimony and was in deliberations — and seemingly leaning to rule against the Angels — the lawyers for Skaggs’ family and the team reached a settlement. It avoided any sort of further appeals and a shared acknowledgement of culpability. Five years of intense litigation was over.

The financial agreement was not disclosed. Rusty Hardin, an attorney for the plaintiffs, contended afterward there were rules in place and the Angels ignored them. “The changes need to be by teams like the Angels who let this happen,” Hardin said.

Speaking after court to the New York Times, jurors indicated that they had already determined the issue of liability before the case settled. Multiple jurors also said the group had decided to issue the Angels all the punitive damages, perhaps as much as $80 million.

The trial spanned nearly nine weeks including the jury listened to testimony and arguments for 32 days.

In the years since Skaggs’ death, the illicit manufacture of opioids have claimed several hundreds of thousands of lives in the U.S.

It hasn’t made it any easier to see several murals popping up around Southern California to remember Skaggs.

Artist Jonas Never created one of Skaggs across the street from the Santa Monica High baseball field. Never was a Samohi product himself, a pitcher on the Vikings years earlier.

“A bunch of Tyler’s former teammates and opponents came together to donate the paint and the Santa Monica Police Department and a local nonprofit helped out a ton too,” Never told mlb.com. “Both Tyler and I wore No. 11 when we pitched at Santa Monica.”

Another mural was painted within days at a wall on Venice Beach:

The Tyler Skaggs Foundation was founded days after his death, and the Major League Baseball Players Association gave a $45,000 donation.

The foundation said its mission was “to provide equitable access to sports programs and recreation, as well as other community initiatives that will help young people build both athletic and essential life skills. By contributing financial support through grants and scholarships, supplying athletic equipment, and raising awareness, our goal is to empower our younger generation through the gift of sports.”

It has supported groups like Santa Monica Pony baseball, batting cages at the North Venice Little League where he played, put on food and toy drives, and created a Santa Monica High scholarship. The home page includes this description:

“Tyler loved to mentor young people, encouraging them to work hard to achieve their dreams, and to provide comfort and lift up those facing significant health challenges. His favorite volunteer stops were Children’s Hospital of Orange County, the Boys & Girls Club of Santa Monica, and the three schools he attended growing up: Roosevelt Elementary, Lincoln Middle School and Santa Monica High.

“ ‘If someone asked him to help out with something, he always went,’ said his mother, Debbie.

“Tyler had a bright future – in baseball and beyond – and he left us too soon. This foundation and its work will ensure that Tyler’s future, now in the form of his legacy, will continue to touch the people’s lives, just as Tyler did when he was among us.”

The winter after Skaggs died, the MLB and its player union agreed to begin testing for drugs of abuse, with those who tested positive referred to medical professionals. Only players who decline treatment are subject to discipline.

The league also began encouraging ballparks and trainers to carry naloxone, which can reverse an overdose if the patient receives it in time.

Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that can be 30 to 50 times stronger than heroin and can be fatal even in low doses, is most often illegally produced and dealers frequently produce counterfeit pills using this cheaper drug but falsely market it as oxycodone, a prescription painkiller.

Both fentanyl and oxycodone were banned as part of MLB’s joint drug prevention and treatment program. In response to Skaggs’s death, the MLB and players union updated their policy to take a treatment-based approach, rather than a punitive one, and to help players who test positive for substances classified as drugs of abuse, like opioids and fentanyl.

MLB said it administered some 12,000 drug tests to players in 2023.

In the summer of 2024, Major League Baseball joined a partnership with the White House called “Challenge to Save Lives From Overdose.” It announced new medical procedures required that required Narcan be available in clubhouses, weight rooms, dugouts and all umpire dressing rooms at MLB and minor-league ballparks, and all certified trainers carry it on plane flights and in team hotels.

Narcan, also known as naloxone, is the drug created to immediately use for opioid poisoning — a nasal spray the blocks the effects.

“I think our experience and our focus on naloxone in our industry will hopefully, just because of the public facing nature of baseball, help with the public awareness and contribute to the national conversation on this,” said Jon Coyles, MLB’s vice president of drug health and safety programs.

“I can’t think of a more important public health issue than this particular one.”

Who else wore No. 45 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

A.C. Green, Los Angeles Lakers forward (1985-86 to 1992-93 and 1999-2000):

Lakers fans knew Green as someone who’d go all the way — never missing a game from 1987 to 2000, a streak that spanned 1,192 games — as well as someone who would abstain.

The first-round draft pick out of Oregon State didn’t fit the mold of L.A. and Showtime.

“I am in this environment,” Green said later in his career, “but the environment doesn’t dictate the norms.” He was nonetheless durable, a rebounding force and a key part of the NBA titles of 1987, ’88 and when he came back in 2000. He was never a candidate for management load.

An All-Star in 1990, Green averaged 11.3 points and 7.9 rebounds in his first eight seasons and left ranked second in franchise history in offensive rebounds and in the top 10 in total rebounds, steals and games played.

In 2011, he was awarded the Bobby Jones Award by Athletes in Action for character, leadership, and faith in the world of basketball, in the home and the community. Green was also inducted into the World Sports Humanitarian Hall of Fame.

Trivia quiz: What do the initials A.C. stand for? His father’s mother is named Amanda and his father’s father is named Chester. And his father is A.C. Senior.

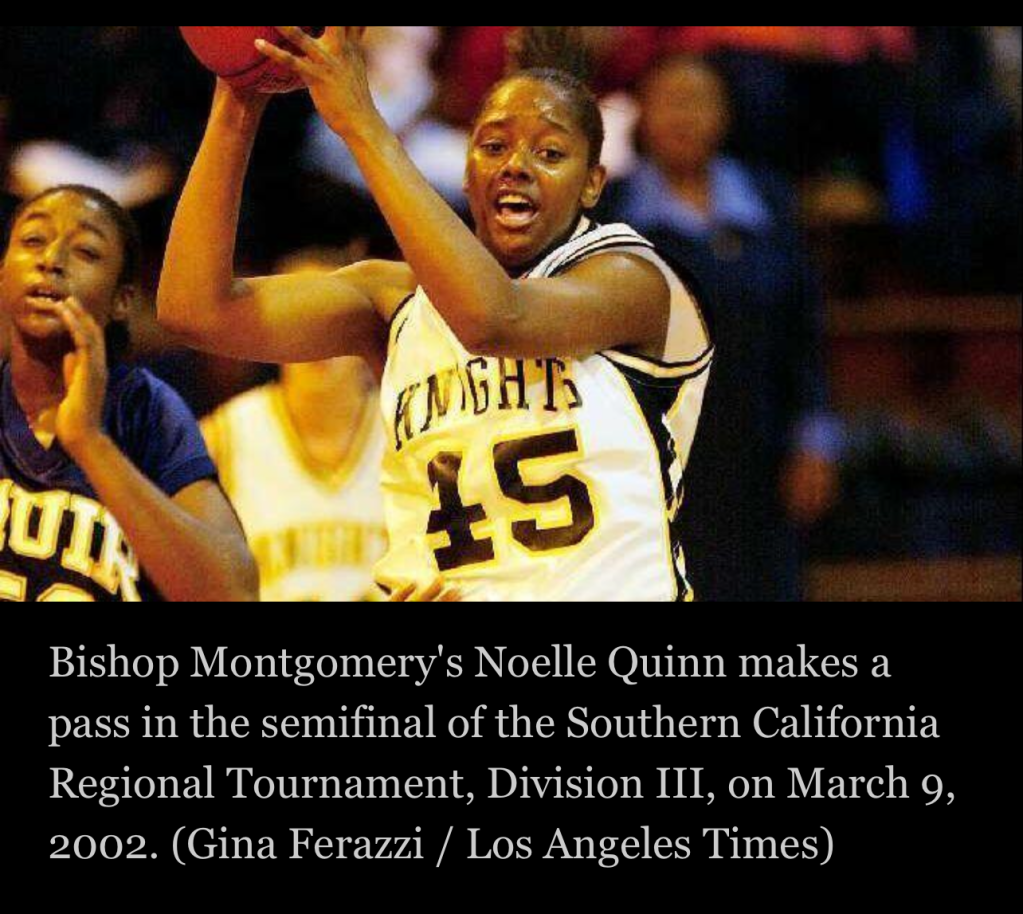

Noelle Quinn, Bishop Montgomery High guard (1998-1999 to 2002-03); UCLA women’s basketball guard (2003-04 to 2006-07), Los Angeles Sparks guard (2009 to 2011):

The first Bruins player — men or women — to total 1,700 points, 700 rebounds and 400 assists in her career over 107 games paved Quinn’s path to the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 2020. A three-time first-team All-Pac-10 player and a two-time Pac-10 All-Tournament honoree, Quinn led UCLA to its first Pac-10 Tournament title by scoring 22 points and hitting a game-tying basket with five seconds left to force overtime in a victory over Stanford. Before that, the Los Angeles-born Quinn led Bishop Montgomery High of Torrance to four state championships, three regional title and three division titles. After that, the No. 4 overall pick by the Minnesota Lynx in the 2007 WNBA draft put in three seasons with the hometown Sparks, and gained votes for Most Improved Players in 2009. The next season she had a career-best 11.2 points a game, starting all 34 games. Her 11-year career ended with a WNBA title as a member of the Seattle Storm, where she later became head coach in 2021.

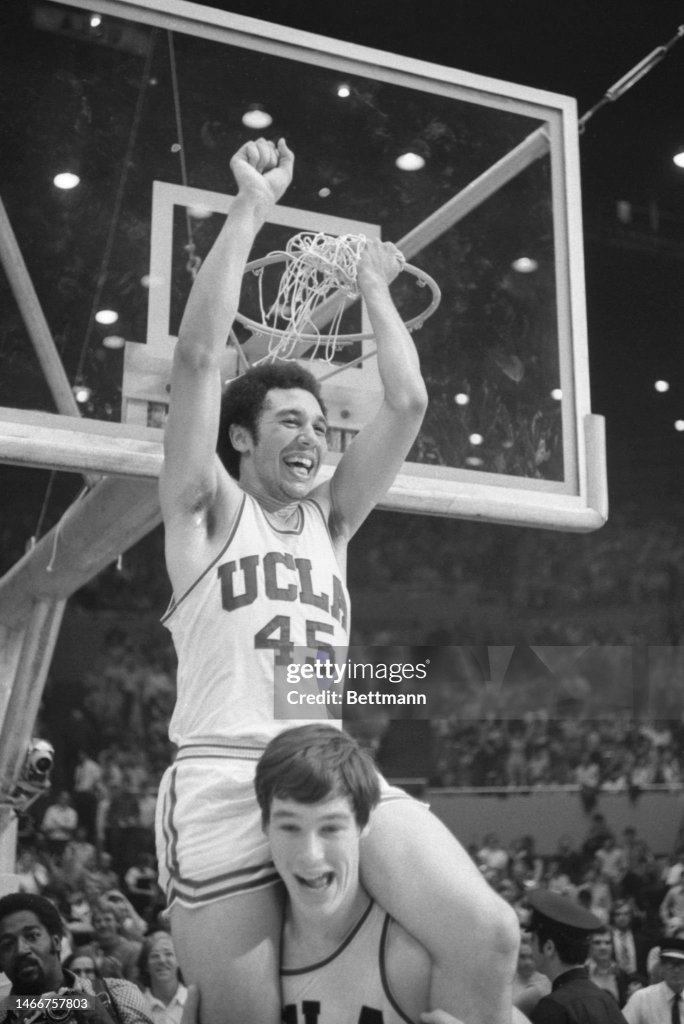

Henry Bibby, UCLA basketball guard (1969-70 to 1971-72):

A three-time NCAA champion and All-American as a senior when his team went 30-0, Bibby was a 2004 induction in the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame for his contribution to teams that went 87-3 in his time on the guard. Bibby also shared MVP honors on the UCLA freshman team with guard Andy Hill in 1969. As a head coach at USC, Bibby’s Trojans teams went 132-120 and made three NCAA Tournaments in his eight-plus seasons.

Andre McCarter, UCLA basketball guard 1973-74 to 1975-76):

A Parade All-American high school guard from Philadelphia’s Overbrook High (which produced Wilt Chamberlain and Walt Hahhzard, McCarter started as a junior on the 1975 title team that would be the last one for coach John Wooden, McCarter averaged five assists a game for the last 60-plus games of his career. Although he was a 10th-round pick by Cleveland in the 1975 NBA Draft, he stayed at UCLA and, after his senior season became a third-round pick by Kansas City.

Jim McGlothlin, California Angels pitcher (1965 to 1969):

Born in Los Angeles and an All-Valley standout at Reseda High in the San Fernando Valley as a senior in 1961, McGlothlin wore No. 50 as a rookie but changed to No. 45, which he wore when he made the AL 1967 All-Star team and pitched two shutout innings in a game played at the new Anaheim Stadium (ending with a 15-inning NL win, 2-1). That season, McGlothlin lead the league with six shutouts among his 12 wins, nine complete games and 2.98 ERA. Nicknamed “Red” for his red hair and freckles, McGlothin was traded to Cincinnati in a deal for future AL batting champion Alex Johnson, McGlothlin made starts in two World Series games for the Reds in 1970 and ’72. He died at age 32 of a rare strain of leukemia in 1975.

Tuli Tuipulotu, Los Angeles Chargers outside linebacker (2023 to present): Out of Lawndale High and USC, Tuipulotu had 8 1/2 sacks for the Chargers in 2024 and 13 total in his first two NFL seasons (34 games). He was named the Pat Tillman Defensive Player of the Year Award as well as a unanimous All-American as a junior in 2022 with the Trojans (wearing No. 49) where he led the conference with 22 tackles for losses and 13 1/2 sacks.

Have you heard this story?

Pedro Martinez, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1992 to 1993):

Perhaps it was shortsighted on the part of the Dodgers’ decision makers, when, in the 1993 offseason, and feeling a need to add a bat to the infielder, 21-year-old Pedro Martinez, who measured up at 5-foot-11 and 170 pounds, was deemed expendable and was sent to the Montreal Expos for 25-year-old second baseman Delino Deshields. The thought, especially from manager Tommy Lasorda, was that Ramon Martinez’ younger brother was just not durable. You’ll find the ’92 Martinez-for-DeSheids deal listed tops among many lists of the worst Dodgers trades of all time. Four seasons in Montreal, seven more in Boston, four more for the New York Mets and one last hurrah for Philadelphia’s post-season run resulted in a career record of 219-100, with 46 complete games, more than 2,800 innings pitched and 11,394 batters faces, striking out 3,154 of them. And a first-ballot Hall of Fame pick based on three Cy Young Awards, two runners up, and five ERA titles. For the Dodgers, his body of work was judged on 67 games — three of them starts, and 115 innings. He would lead the NL in single-season pitching WAR at 9.0 (with Montreal, 1997), and lead the AL with 9.8 (with Boston, 1999) and 11.7 (again, Boston, 2000) among his eight All Star seasons. Let it be noted: Martinez did come in ninth in the NL Rookie of the Year voting in 1993 after a 10-5 record with a 2.61 ERA in 65 games, but not enough to usurp teammate Mike Piazza — who also would leave the Dodgers when … let’s not even go there.

We also have:

Gabe Dynes: USC basketball center (2025)

Rickie Hawthorne: Verbum Dei High basketball center (1969 to 1972)

Pete Richert, Los Angeles Dodgers relief pitcher (1962 to 1964; 1972 to 1973)

Ken Boyer, Los Angeles Dodgers third baseman (1968 to 1969)

Chris Gwynn, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (1987 to 1991, 1994 to 1995)

Ron Perranowski, California Angels pitcher (1973)

John Candelaria, California Angels pitcher (1985 to 1987)

Jim Bertelsen, Los Angeles Rams fullback (1972 to 1976)

Sean Rooks, Los Angeles Lakers center (1996-97 to 1998-99); Los Angeles Clippers center (2000-01 to 2002-03)

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 45: Tyler Skaggs”