This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 81:

= Tim Brown, Los Angeles Raiders

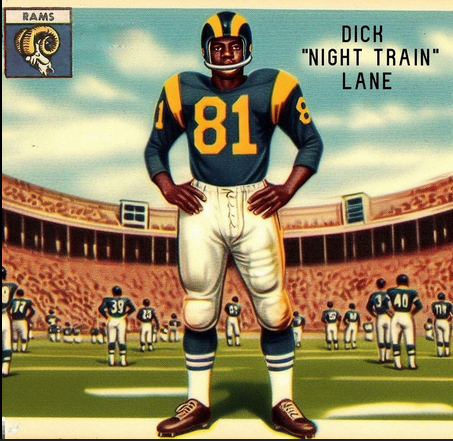

= Dick “Night Train” Lane, Los Angeles Rams

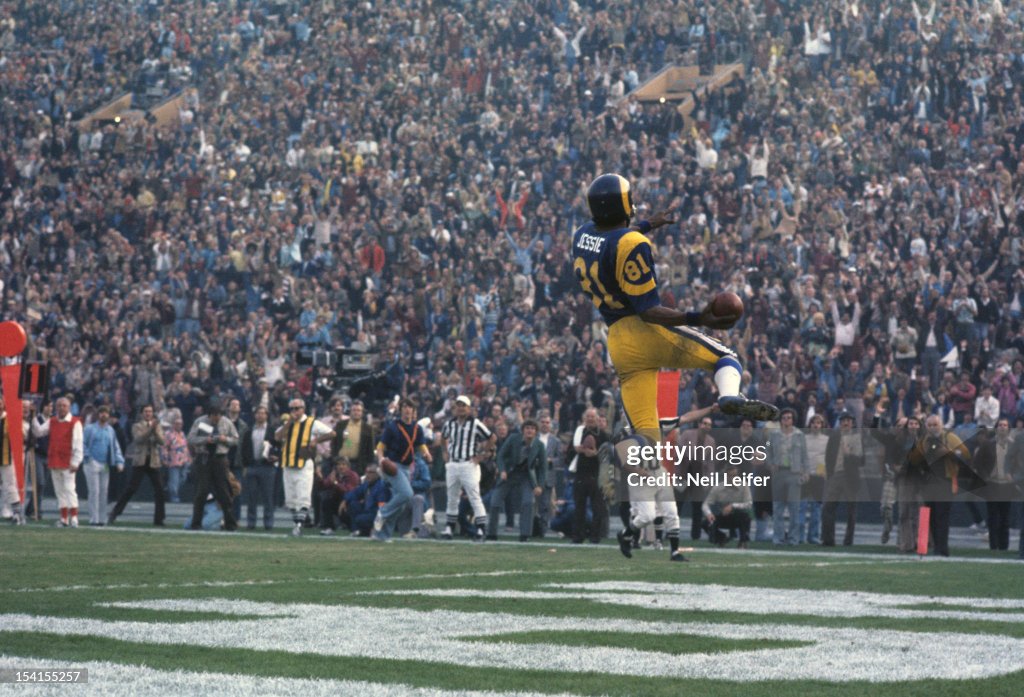

= Ron Jessie, Los Angeles Rams

The no-so obvious choices for No. 81:

= Don Hardy, USC football

= Mike Williams, Los Angeles Chargers

The most interesting story for No. 81

Dick “Night Train” Lane, Los Angeles Rams right defensive halfback (1952 to 1953)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Los Angeles Coliseum, Redlands

Richard Lane really had nothing to lose.

On a summer day in 1952, the 24-year-old Army veteran worked up the courage to walk into the Los Angeles Rams’ offices on Wilshire Blvd. He carried a scrapbook of all the stories and photos that documented the football he had played in his lifetime — high school, junior college, U.S. Army military base.

Maybe the defending NFL champs could find a job for him. At least give him a tryout.

The idea struck him because he passed by the team’s building every day he rode the bus to his job at an aircraft plant. He moved to Southern California looking for work, and the best he could find was lifting heavy, oily sheets of metal out of a bin and placing them on a press.

Maybe the Rams, a team proactive in finding talented African-American players that started a few years earlier with their move to L.A. with recruiting Kenny Washington, would be his best chance.

It worked.

The stellar 6-foot-3, 195-pounder had his sights set on becoming a receiver, so the team gave him No. 81. His Hall of Fame future was as a defensive back, with a tenacious style of tackling that would eventually be outlawed.

As a rookie, Lane set a NFL regular-season with 14 interceptions, accounting for 298 returns yards, two touchdowns plus a safety — one of the greatest years a defensive player experienced in league history. Then or now. Consider that was all in a 12-game season, and it still hasn’t been matched.

The record would be so remarkable, it was put on his tombstone.

But for someone whose lyrical, legendary nickname came from a popular jazz record, Lane’s career was far from a one-(vicious)-hit wonder.

After the 1953 season, Lane took his gloriously cool new nickname eventually to Motown through Chicago. Away from the Rams, Lane made seven Pro Bowl teams, part of the NFL’s 1950s All-Decade team, the NFL’s 75th Anniversary team and a 1974 Pro Football Hall of Fame selection, ranked No. 20 in The Sporting News’ list of the 100 greatest football players. In 1969 he was chosen as the NFL’s best cornerback of the league’s first 50 years.

The Rams gave him a beginning, but not an ending. It showed its willingness to accept African-American talent at a time when it wasn’t all that accepted, but it didn’t follow through. It failed to see how a life that had been so extremely challenging and difficult to that point wasn’t worth a full investment.

The train left the station too early for SoCal observers to fully appreciate.

The background

Ella Lane was a widow with four children, walking home on a warm summer evening behind a row of houses on East 9th Street in Austin, Tex. She heard what she thought was a cat crying. There was a 3-month old baby boy, wrapped in newspaper, buried in a trash can.

She took the baby home and she adopted him. His name would be Richard.

Johnny Mae King, a local prostitute, was his actual birth mother. His father was the pimp.

“My father was called Texas Slim,” Lane would later say, not knowing his circumstances until he was 11. “I never saw him – I don’t know if he’s the one that told my mother to throw me away. A pimp told my mother I had to go. I never made any attempt to meet my dad. I figured if he didn’t want me around, I didn’t want to meet him, either.”

Lane bussed tables, shined shoes and helped Ella Lane, his rescuer, with her backbreaking home laundry business.

The first nickname Richard Lane pocketed was “Cue Ball.” He remembers it came about while hustling in a pool hall. And winning. The guy he just beat started to run to avoid paying. Lane chased out after him, cue ball in hand. Lane had an arm, too. He threw it, hitting the miscreant upside the head.

Maybe that’s called foreshadowing.

Because he had a sense of playing football with his friends in the neighborhood, Lane got onto the L.C. Anderson High School’s football program. The team won the Texas state championship in 1944 when he was a junior, and they were back in the playoffs his senior year.

That’s when Lane had heard that Johnny Mae, who spent several years in prison for shooting and killing Lane’s birth father., had been released, moved to Scottsbluff, Neb., got married and opened a tavern.

After his high school graduation, Lane wanted to visit her, looking for answers.

Johnny Mae agreed to pay his tuition at Scottsbluff Junior College (later known as Western Nebraska Community College). Lane was the only the only African-American player on the predominantly all-white team.

His overall athletic ability was acknowledged quickly as Lane played in a pickup baseball game the summer of ’47, the year Jackie Robinson broke the MLB color barrier. A scout from the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro National Baseball League, Robinson’s former team, got Lane to agree to play for its affiliate in Omaha. Lane signed under the name Richard King so even as he was paid, he could stay amateur and remain eligible to play college football.

While he was playing baseball, Lane heard his adopted mother, Ella, was ill and about to die. He he went back to Austin to see her. At that point, Lane was a Junior College All-American for Scottsbluff’s football team and set to play his second year, maybe draw the attention of a major college. Back in Austin, Lane heard Johnny Mae was working the streets again as a prostitute.

He never went back to Nebraska, quit school, and joined the U.S. Army. He would serve four years and become a lieutenant colonel.

After basic training at Kentucky’s Fort Knox, Lane was based at Ford Ord in Monterey Bay, Calif. In addition to playing baseball and basketball, Lane was a receiver on the base’s football team. He caught 18 touchdown passes in 1951 and was named first-team All-Army. Lane heard the San Francisco 49ers might be interested in him, but he never followed up.

Leaving the military in 1952, Lane married, had a son, and saw a chance to work in Southern California in the hiring boom during the Korean War.

Day after day, on the bus to work, he passed the Los Angeles Rams’ office complex. An Army buddy, Gabby Smith, who as a free agent played for the Rams a few years earlier, put the idea in Lane’s head to at least talk to someone there about a tryout. The scrapbook filled with clips from high school, junior high and his days in the military was all Lane had. The sheet metal job he had making a living was demoralizing.

“They told me I’d be a filer,” Lane once said, quoted in the book, “The Football 100,” where he was listed at No. 51 all time in the game’s history. “I though they meant a file clerk in an office. I was a filer, all right. I filed big sheets of metal into bins with oil dripping off the metal onto me.”

He said that each night, his wife Geraldine “would have to shampoo my hair a number of times just so I could get clean enough to ride the bus to work the next day.”

Lane remembered how he walked into the Rams’ offices and said: “I’d like to talk to your coach. I can’t remember his name, I know it starts with an ‘S’.”

Rams head coach “Jumbo Joe” Stydahar, impressed with Lane’s size, knew it would be tough for him to make the team with two future Hall of Fame receivers, Tom Fears and Elroy “Crazylegs” Hirsch, already as his starters. Styhahar still offered Lane a chance at a $4,500 contract if he made the roster.

Lane’s break came when injuries at the team’s training camp at the University or Redlands hit the Rams’ defensive backfield. To fill spots, he was moved to the other side of the ball.

An August, 1952 L.A. Times dispatch from training camp after the team’s first scrimmage picked up on Lane’s ability immediately. Wrriter Frank Finch describe Lane as “the outstanding player in the scrimmage by a country mile.” He added that the “a spidery Negro rookie” at defensive halfback was “practically ferocious as he made tackles all over the lot.” Most notably was a play where Lane didn’t give in to a deke by Hirsch and “he dropped Hirsch with a devastating tackle.”

“Lane came out here to make the ballclub,” said Stydahar. “Well, last night he got himself a job.”

The story may have also been the first to reference what would be a genius branding opportunity for him — Night Train.

“Night Train” was the title of saxophonist Jimmy Forest’s R&B No. 1 instrumental hit, borrowed from a Buddy Morrow tune. The Rams’ Tom Fears played it on his phonograph in his dorm room. It was said that Lane was often “found in the hall … dancing to the music.”

The song reverberated more like something from a strip club than a blue’s revival.

”Every day I’d be going to his room and he’d be playing it,” Lane once recalled about Fears. “He roomed with a guy named Ben Sheets, and whenever I’d walk into the room, Sheets would say, ‘Here comes Night Train.’ He started calling me that, and it stuck.” Lane added in 2001: “I’d been called all sorts of names by that time, I wasn’t sure what they meant by that nickname.”

It meant, in some ways, that Lane was a run-away train in the process of hitting opponents. The name gave him status, like a wrestling hero who had a famous take-down move. In this case, his tackles were called the “Night Train Necktie.” It involved grabbing the facemask, twisting the head and risking serious injury to the receiver. Opposing coaches who wanted to protect their best receivers learned not to have the quarterback throw in Lane’s direction.

“Quarterbacks avoided Night Train’s part of the field like a hunter would avoid a rattlesnake next,” the L.A. Times’ Jim Murray once wrote. “There were games in which Night Train had more receptions than the receivers he was covering.”

In 1954, a newspaper story described a play in a preseason game that Lane made against the Washington Redskins’ Charlie “Choo Choo” Justice. The headline was: “Night Train Derails Choo Choo.”

In 1952, Lane’s record-setting 14-interception season was even more remarkable in that he didn’t make his first pick until Week 4. Teammate Herb Rich had been among the NFL leaders at that point with six after the first four games, so opponents we learning to avoid him. But there instead was Lane.

Lane played off the receivers to make it appear they were wide open. Lane made up for the real estate difference with his speed and thrust. Then came the tackle — clotheslining as it would be called — with his elbow around the receiver’s necks.

Six of Lane’s 14 interceptions, and both of his TD returns, came in the season’s last two games against Green Bay and Pittsburgh. In the Rams’ playoff loss to Detroit, Lane was shut out by Lions quarterback Bobby Layne, who learned his lesson during Week 4 of the regular season when he was the victim of Lane’s first career interception.

The NFL didn’t give out Defensive Player of the Year Awards until 1967.Lane was far ahead of his time for honors.

In a 1981 story, Lane admitted: “I had no idea — no it wasn’t even in my dreams — that football would ever do for me what it did. I wasn’t looking beyond that first year. I thought if I could make that $4,500, I’d be able to find a better job and maybe get a car and a decent place to live.”

The ’52 Rams finished 9-3, second in the NFL’s National Division. But Lane had immediately lost his greatest ally in Stydahar.

Stydahar, who grew up working in the West Virginia coal mines and was known as a vicious tackler during a career that got him into the College and Pro Football Hall of Fame, saw the raw talent Lane brought. Stydahar knew his stuff, as the 9-3 Rams in his first season lost to Cleveland in the NFL title game of 1950. Stydahar buided the Rams to an 8-4 record and NFL title in ’51 over Cleveland at the L.A. Coliseum, played before a then-record crowd of nearly 60,000.

After the Rams’ ’52 season opening loss to Cleveland, dissension between Stydahar and backfield coach Hampton Pool boiled to the surface and Rams owner Dan Reeves gave Stydahar a $11,900 buyout of his contract. Pool was promoted to head coach.

After Lane blocked two field-goal attempts during a July 1953 scrimmage, Pool remarked: “Night Train has the reflexes of a cat. It just doesn’t seem possible that a man can come in from so far out and get in front of the ball in a matter of a couple of seconds.”

In 11 games during the ’53 season, Lane had only three picks, for nine yards. His first interception wasn’t until Week 7. His only real stat of note was recovering a fumble for a touchdown — he blocked a field-goal attempt by Green Bay’s Fred Cone, picked the ball up as it bounced near midfield, and had a clear path to the end zone.

The Rams finished 8-3-1, third in the NFL West. Lane was disillusioned with how Pool and the Rams used him less as a defensive back and more as a defensive end/pass rusher lined up closer to the offensive tackle.

Lane couldn’t bargain for a larger paycheck for the ’54 season — he was offered only a $2,500 salary increase. So he asked the Rams to trade him. They foolishly did.

In a three-team deal, Lane went to the Chicago Cardinals in ’54. The Cardinals coach was Joe Stydahar.

Back as a right safety with Ollie Matson, and a teammate of future Hall of Famer Charlie Trippi, Lane again led the NFL again with 10 interceptions for 181 yards and was a Pro Bowl pick. The Cardinals didn’t fare as well, finishing 2-10 for Stydahar’s second-straight 10-loss season and he was fired. But the Rams dropped to 6-5-1 without him and fourth in the NFL West.

For six straight seasons in Chicago, Lane was a four-time Pro Bowl pick even as the teams only occasionally finished above .500 while playing home games at Comiskey Park. Lane also got to play some receiver as the team tried to make use of his talents as a two-way star– he established the longest reception in franchise history with a 98-yard touchdown reception he took practically all the way up the field by himself.

In 1960, as the NFL was ruling to outlaw the clothesline tackle, Lane was dealt to Detroit for a throwaway place kicker. But that gave Lane another six years with three more Pro Bowl selections. The NFL’s ban on the tackle came finally in 1961, when Lane received blowback for a hit he put on the Rams’ Jon Arnett, creating an iconic photo and led to the league image in damage control.

Regardless, Lane was quoted as saying about how he played defense: “Coverage was a lot different then. There were no zones — all man-to-man. The league was smaller. You really came to have a friendship with the receivers you covered, guys like (Lenny) Moore and (Jon) Arnett. It was tough just getting a hand on them much less tackle them.”

After two seasons seeing the Lions last in the NFL West playing at Tiger Stadium, Lane retired. His last interception was recorded against Baltimore’s Johnny Unitas in a 34-0 loss in October of ’64, after which Lane was put on waivers and went unclaimed.

Lane left the game with seven NFL records. His 68 picks were second all-time and now sit No. 4 on in league history. Even as the NFL’s regular season has expanded to 17 games, Lane’s single-season mark of 14 interceptions remains the high point more than a half century later. The Raiders’ Lester Hayes was the latest to challenge it with 13 picks in 1980’s 16-game season.

Lane and all-time leader Paul Krause (81) are the only two players in NFL history with two seasons of 10 or more interceptions. Both of Krause’s seasons were 14 games long. Both of Lane’s seasons were a dirty dozen.

The stats only add to Lane’s folk lore.

“He came from Texas and spoke a language that not quite everyone could understand,” said writer George Plimpton. “He understood a lot of what he was saying.”

In Plimpton’s famous book, “Paper Lion,” he quotes former Lions assistant coach Aldo Forte trying to recount a hit Lane put on New York Giants quarterback Y.A. Tittle in 1962 that he said “literally knocked the plays out of his head.” Lions teammate Alex Karras also told the story about how Detroit management alled many of its star players into a room one day to try to get them to accept less money in their contracts. The ploy was to show the players howthe concession stand prices were going up for fans as the team needed to meet its costs. “Night Train was in the back of the room just steaming,” said Karras. “He raised his hand and said, ‘I am under the consumption that there ain’t no more money?’”

The legacy

After Lane’s retirement, Lions owner William Clay Ford hired him as a special assistant. Lane stayed there seven years as Ford’s liaison between the players and front office.

Lane had several short stints as an assistant coach at Division I-AA and Division II schools. Having once met comedian Redd Foxx while Lane played for the Rams, he was hired by Foxx as his body guard and road manager. That lasted a year.

Lane returned to Detroit where he was in charge of the city’s Police Athletic League youth athletics programs for many years.

In his 1974 Pro Football Hall of Fame speech, Lane called the league out for its mistreatment of black players as “stepchildren” and added: “I hope the black players will band together to deal with the problem of no black coaches, no black managers and few black quarterbacks in pro football.”

Lane was just the second defensive back ever enshrined at the Hall, and also only the seventh African-American.

A 2001 biography on Lane by Mike Burns, with a forward from Pat Summerall, detailed more about Lane and his three marriages, including the brief time he had with jazz and blues singer Dinah Washington, known as the Queen of the Jukeboxes, inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall of Fame. She died of a drug and alcohol overdose at age 39 in 1963.

Summerall, a kicker and end who was Lane’s teammate on the Cardinals, said, ”I played with him and against him, and he’s the best I’ve ever seen.”

”Night Train was the best defensive back ever to play the game,” Herb Adderley, the Green Bay Packers’ Hall of Fame cornerback, once said. ”I’ve never seen a defensive back hit like him. I mean, take them down, whether it be Jim Brown or Jim Taylor.”

In 2022, Dick Lane’s two sons — Richard Walker Sr., and Richard Lane, Jr., the later of whom grew up in Los Angeles — explained to an Austin, Tex., TV station it wasn’t until their father’s funeral in 2002, when he died at age 73 from diabetes and immobility from numerous knee surgeries, that many of the siblings first met each other.

In a 2002 obituary for the Los Angeles Times, longtime NFL writer Bob Oates, who covered pro football in L.A. newspapers for 60 years, wrote about Lane: “He was far and away the greatest pass interceptor of all time. When I think of him, I think of how far in the air he used to get to make his interceptions. I’d never seen a defensive back who could jump as high as Night Train. He could play today and be All-Pro.”

The sons believed their dad suffered from CTE issues. When Lane died, CTE hadn’t been diagnosed and it was too late to take samples of his brain. The NFL dismissed any of his family’s claims.

That left the brothers even more angry about how the NFL treated their father in his older years as he was living off a $695 a month league pension. The sons petitioned the Alumni Dire Need Fund and were turned away.

Jane Arnett, the wife of former USC and Rams star Jon Arnett, told the story in 2019 about how she said she there was a real problem about players from pre-1993 (like her husband) who did not get enough support from the league. When Lane passed away, she said “there was no money to bury him. There was talk of him having a pauper’s funeral, which, unfortunately, happens to a lot of people. But it was shocking that it would happen to a man like that.”

She said people did eventually step in to help cover the funeral costs — but the situation raised red flags.

A 2024 documentary called “Train” by Eric Herbert — a project started by Lane’s two sons that includes a website called ntl81 — Lane’s contemporaries such as Dick Butkus, Fred “The Hammer” Williamson and Dick Le Beau talked about his legacy. Some of that includes how Lane remains as a figure in the Madden NFL video games.

On Lane’s Pro Football Hall of Fame web page, a quote is enlarged that speaks to his spirit of how he saw his job in the NFL: “My object is to stop the guy before he gains another inch. I’m usually dealing with ends who are trying to catch passes, and if I hit them in the legs they may fall forward for a first down. There is nothing I hate worse than a first down.”

In his New York Times’ obituary, it noted Lane often visited nightclubs on the road and saw an affinity between athletes and jazz musicians.

”A musician’s got to have a style — maybe it’s a way of holding the horn or playing a phrase,” Lane once remarked. ”That’s what I was always after. I wanted to create my own style of playing.”

Another quote attributed to Lane: “It is a sign of a coward who says, ‘This is my bad luck and I will have to accept it.’ A positive thinker would say, ‘I will decide my fate and my own destiny’.”

Who else wore No. 81 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

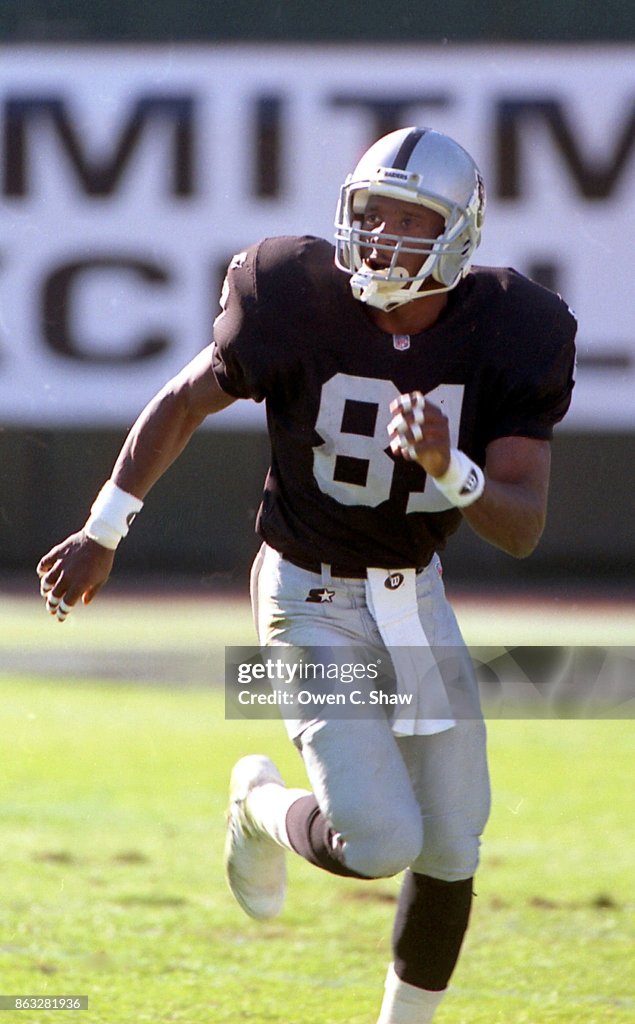

Tim Brown, Los Angeles Raiders receiver (1988 to 1994):

The Pro Football Hall of Famer started his pro career as the Heisman Trophy winner out of Notre Dame (the first to win the award officially as a position receiver) with the sixth overall pick in the 1988 NFL Draft. As a 22-year-old, he made the Pro Bowl his first year primarily by leading the league with a rookie record 2,317 all-purpose yards –1,098 came from 41 kickoff returns, 444 from 49 punt returns, 725 yards from 42 catches and even 50 yards rushing from 14 attempts. Three more Pro Bowl seasons came for Brown while the Raiders were in L.A., and five more after the franchise moved to Oakland, where he had nine seasons in a row of 1,000 yards receiving or more, and led the NFL with 104 catches in ‘97. The most interesting gap in his career was not playing in the NFL in 1999 and 2000, but coming back as a Pro Bowl player at 35 in 2001 and returning a punt 88 yards for a touchdown — the oldest NFL player to score on a punt return. Leaving the Raiders after 2003 as its franchise leader in games played, receptions, receiving yards and punt returns, Brown was the last Los Angeles Raider to stay in Oakland. At 38, he came back to play one more year with Tampa Bay (and former Raiders head coach Jon Gruden) for a final season. He signed a one-day contract in 2005 to retire with the Raiders, leaving with 14,934 yards receiving (second most in NFL history) and 19,682 combined yards (fifth all time), to go with 105 touchdowns total.

Ron Jessie, Los Angeles Rams receiver (1975 to 1979):

The All-American long jumper at Kansas spent his only Pro Bowl season in 11 years with the Rams in 1976 when he caught 34 passes for 779 yards and six TDs. He was a dependable No. 2 receiver with Harold Jackson and Preston Dennard. Jessie became the beneficiary of a new form of free agency when, after his rookie year in Detroit, he signed with the World Football League, but the team folded. After playing out his contract in Detroit, he signed with the Rams. The NFL ruled that Detroit deserved some sort of compensation as Bryant filed a temporary restraining order that he would never play for the Lions. His time with the Rams after his Pro Bowl season was often spent injured, and a broken leg prevented him from being with the team in the 1980 Super Bowl. As a scout for the Rams after retirement, Jessie died from a heart attack at age 57 in Huntington Beach.

Mike Williams, Los Angeles Chargers receiver (2017 to 2023): The Chargers’ seventh-overall draft pick in 2017, the 6-foot-4, 218-pounder out of Clemson had 4,806 receiving yards on 309 catches in 88 games for the franchise with 31 touchdowns. He led the NFL with an average of 20.4 yards a catch in 2019.

Don Hardy, USC football left end (1943 to ’44, 1946): The 1944 All-Pacific Coast Conference left end out of Fairfax High would eventually be drafted by the Los Angeles Rams in 1947 but never play. He was the younger brother of Jim Hardy, an All-American quarterback at USC who played for the Rams in their inaugural season in L.A. of 1946.

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 81: Dick “Night Train” Lane”