This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 30:

= Nolan Ryan: California Angels

= Maury Wills: Los Angeles Dodgers

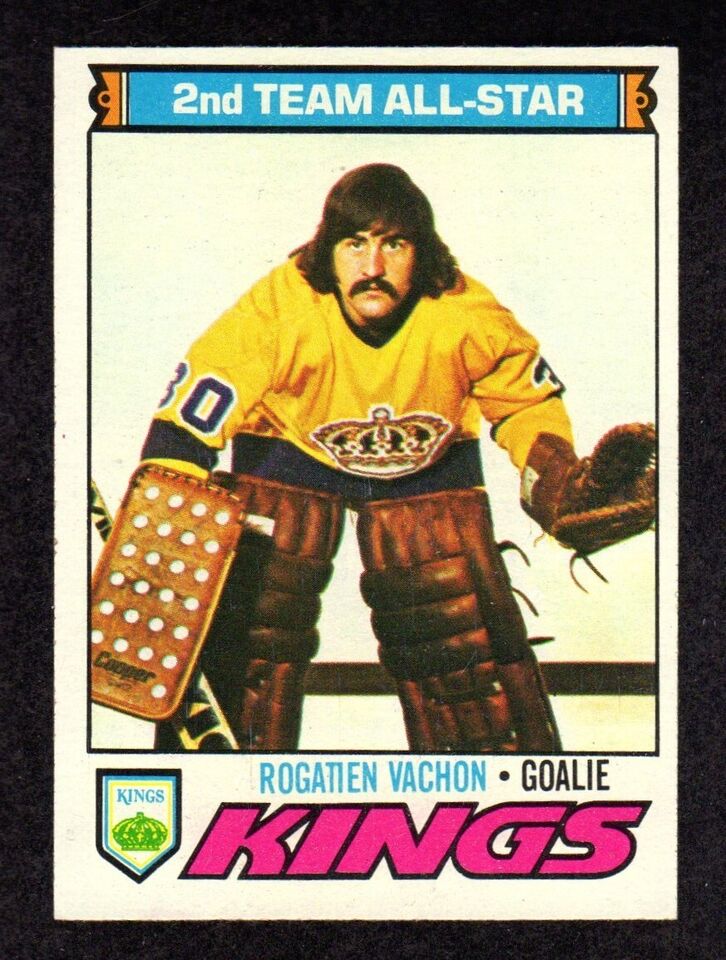

= Rogie Vachon: Los Angeles Kings

= Bo Kimble: USC, Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles Clippers

= Dave Roberts: Los Angeles Dodgers

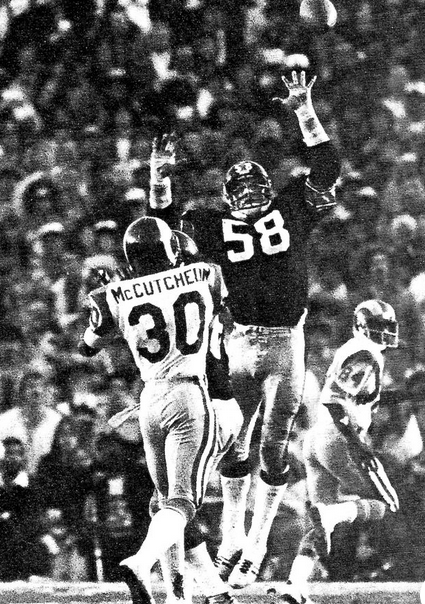

= Lawrence McCutcheon, Los Angeles Rams

The most obvious choices for No. 44:

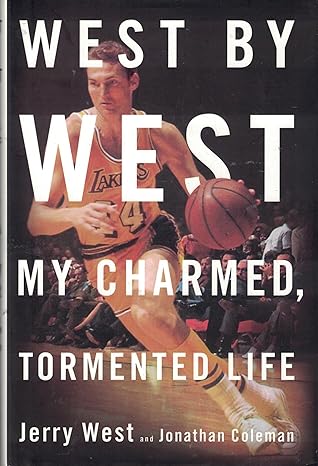

= Jerry West, Los Angeles Lakers

= Reggie Jackson, California Angels

= Darryl Strawberry, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Gaston Green, UCLA football

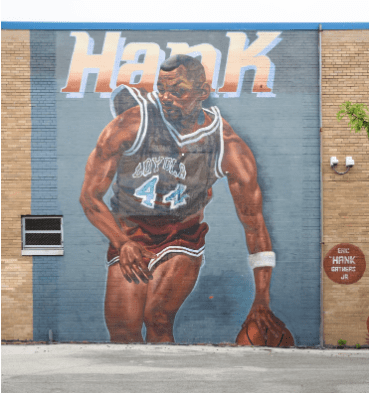

=Hank Gathers, USC, Loyola Marymount basketball

= Cynthia Cooper, USC women’s basketball

The most interesting stories for Nos. 30 and 44:

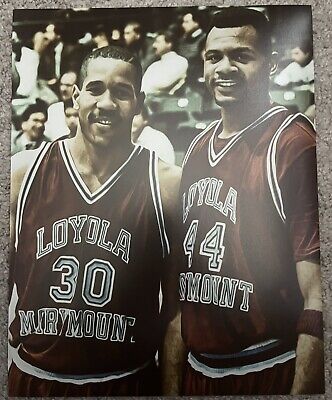

= Bo Kimble: USC basketball guard (1985-86), Loyola Marymount basketball guard (1987-88 to 1989-90), Los Angeles Clippers guard (1990-91 to 1991-92)

= Hank Gathers: USC basketball forward (1985-86), Loyola Marymount basketball forward (1987-88 to 1989-90).

Southern California map pinpoints:

Westchester, Long Beach Sports Arena, L.A. Sports Arena

Bo Kimble shot from the hip launching into a 2015 essay for The Players Tribune with this revelation:

There was a time when all I wanted was to be wherever Hank Gathers wasn’t.

In this 49-year-old version of Kimble, at a point when it was 25 years removed when he last saw Gathers alive, he was just being honest.

When they first met as 13 year olds and played high school ball together at Dobbins Tech in Philadelphia, eventually winning a Public League City title in 1985, “it was hard for us to share” the basketball, Kimble explained.

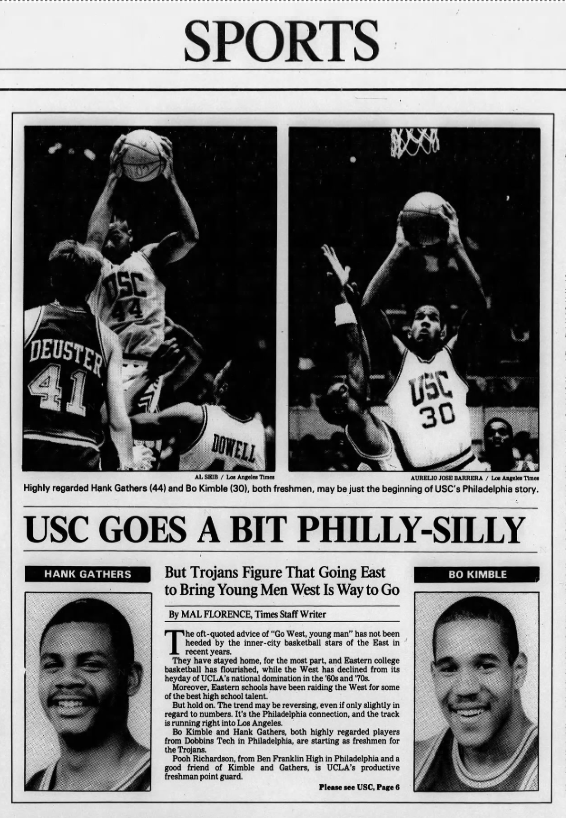

But when USC showed an interest in the 6-foot-7 forward Gathers, and assistant coach David Spencer came all the way East to convince him to leave home and travel 3,000 miles to be part of a roster with some highly-recruited freshman for head coach Stan Morrison, the 6-foot-5 swingman Kimble thought it over as well. He also liked Spencer. He decided to follow Gathers.

It was a good fit.

The Trojans finished last in the Pac-10 during their freshman season, yet “Hank and I didn’t want to leave … We loved USC,” Kimble continued. But when USC had decided to replace Morrison, as well as Spencer, with a new voice — tried-and-true Philadelphia-native George Raveling — Kimble and Gathers did their due diligence.

A bit farther West of USC’s downtown campus was Loyola Marymount University in Westchester, and a another Philly native, Paul Westhead, was performing his magic act.

A player revolt had exiled Westhead from the head coaching job with the Los Angeles Lakers just 18 months after he guided them to an NBA championship in 1980. College was where he was a better fit as a teacher, including a nine-year run at LaSalle in Philadelphia that led to two NCAA Tournament appearances.

Professor Westhead was back in the college game experimenting with this insanely unique style of play — time-is-of-the essence, maximize-the-shot-clock, go-go-go basketball. The recruits at this otherwise docile Catholic university near the ocean were buying into it.

For Kimble and Gathers, this was another very good fit.

Even though they wanted separate housing, separate classes, and separate friends. In preseason pick up games, they even wanted to be on separate teams, neither one allowing the other to win.

But during the games that counted at LMU, they counted on either other. They were inseparable.

“Running the floor coast-to-coast, lots of touches, lots of shots — it was a dream offense,” Kimble said about this calculated full-court press that forced turnovers, fast breaking off rebounds on prescribed routes, shooting the ball somewhere, somehow within seven seconds of gaining possession, and simply wearing the opponents down.

As good a fit it was for Gathers and Kimble, it gave the opponents fits.

In their sophomore season, as LMU averaged an NCAA-record 110.3 points a contest, Kimble and Gathers accounted for 45 points a game. They made it to the second round of the NCAA tournament. As juniors, Gathers somehow led the NCAA with both a 32.7 points per game average (with 1,015 points) and 13.7 rebounds a game, many of them on the offensive end, leading to put-back baskets. Again, LMU recorded a record 112.5 points a game. But the team didn’t make it past the first round of the NCAA Tournament.

As seniors, Kimble and Gathers stepped it up and increased the tempo, their bodies used to this rigor. With teammate Jeff Fryer deadly from 3-point land, LMU cranked it up to a ridiculous 122.4 points a 40-minute game at a time when most teams were fortunate to break 60.

Kimble became the WCC Player of the Year with a nation-leading 35.5 points a game average and a school record 1,131 points – again, the only player in the country scoring more than 1,000 points.

“I never wanted to lead the nation in scoring until Hank did it,” Kimble said. “We made each other better.”

Gathers’ 29.0 points a game was sixth-best in the country. He had a conference-best 10.8 rebounds a game. Both were consensus second-team All-Americans.

“From high school to USC to Loyola Marymount, Hank and I continued to thrive together. Everything seemed perfect,” Kimble went on with his story.

March Madness was coming in like a lion — a roaring group of Lions. Westhead’s team had secured another WCC regular-season conference title, held a Top 20 ranking since New Year’s Day and was building up to the 1990 NCAA Tournament for Gathers’ and Kimble’s final college season.

“When I watch a game on television, and see a team meandering up the floor on offense, then meandering down on defense, it’s only playing half the game,” Westhead was quoted during that ’90 season. “I think you should play a full game. Time is precious.”

Westhead, Kimble, Gathers, their teammates, and the rest of the college basketball would would soon understand those last three words on a much more profound level.

Bryant Gumbel looked across the desk at NBC’s “Today” show in New York in January of 1990 and started an interview with the question: Is it true when you in high school, at the first practice, you two had a fight?

“That’s true,” said Gathers. “We knew we had to get to know each other and we thought being physical would be the best way.”

Kimble laughed. “It was just our competitive nature,” he admitted.

Gregory “Bo” Kimble was born 10 months before Eric “Hank” Gathers but they still ended up in the same grade, on the same teams, trying to accomplish the same things.

USC brought Gathers and Kimble to L.A. for the 1985-86 season to team up with local stars Tom Lewis (Mater Dei High) and Rich Grande. They were known as the “Four Freshmen.” But new athletic director Mike McGee decided to insert himself in the process.

Stan Morrison, who in his seven seasons at USC had won a Pac-10 title and been to two NCAA Tournaments, suddenly wasn’t connecting with the players he just recruited, McGee decided. Not only was Morrison let go, so was key recruiter David Spencer.

That didn’t sit well with Kimble and Gathers.

The Four Freshmen, it was reported, wanted a say in who was to be leading the program in these pre-transfer portal days. They didn’t get that voice. George Raveling gave them a deadline to decide if they were going to stay.

“You can’t let the Indians run the reservation,” Raveling famously told the media. “You’ve got to be strong, too. Sometimes you have to tell them that they have to exit.”

Only Grande stayed. Lewis went to Pepperdine. Gathers and Kimble weren’t interested in joining him in Malibu. Actually, Paul Westhead admitted he first thought he wanted to invite Lewis to LMU. Instead, he focused on focused on Gathers and Kimble, and that came with the recommendation of Fr. Dave Hagen, a mutual friend from back in Philadelphia. Fr. Dave was the mentor to Gathers and Kimble and was able to steer them Westhead’s directions.

Westhead was five seasons removed from coaching the Los Angeles Lakers to the NBA title over Philadelphia, sparked by rookie Magic Johnson and veteran Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. That gig really happened by accident — an bike accident that occurred to then-Lakers head coach Jack McKinney, incapacitating him, and elevating top assistant Westhead to the head job.

A year after the title run, Westhead thought how interesting it might be to implement this fast-break-style offense with the Lakers. It was pre-“Showtime” thinking, but think now about how that all came together later in that decade.

The Lakers’ players collectively pushed back, but Magic Johnson pushed the hardest. They felt they already had a successful system. Pat Riley, Westhead’s top assistant, was put into place for the start of what would be a Hall of Fame caliber career at Westhead’s expense.

After his unceremonious firing, and a season spent trying the implement the speed-it-up offense with a pre-Michael Jordan Chicago Bulls roster, Westhead came back West to LMU in 1985. He could also go back the slings and arrows of an English professor as well as coach basketball, somewhat under the radar of the UCLA and USC realm, but none-the-less in the West Coast Conference that had the ability to stand out with the right combination of coaches and players.

Westhead recalled the first recruiting meeting he had with Kimble and Gathers, showing them game film of the LMU fast-break system. At one point, Kimble put his arm on Westhead’s shoulder and said: “Coach, you’re from Philly; we’re from Philly. Don’t bullshit us with this made-up video of your team’s fast break. Nobody runs that fast.”

Westhead had to convince them it was authentic.

“Count us in,” they said.

The Guru Of Go would have to wait for his star pupils after they sat out a transfer year. Then this upgraded high-wire act would be back in play like the game had never really seen before.

In the 1987-88 season, Kimble only started 15 of 24 games. Gathers started all 30, pulled in 8.7 rebounds a contest, and the Lions went from 12-16 the year before to a 28-4 mark, 14-0 in the West Coast Athletic Conference. Despite a No. 15 ranking in the final AP poll, LMU was handed a meager No. 10-seed in the NCAA West Regionals. The Lions disposed of seven-seeded Wyoming and Fennis Denbo in the opening round, 119-115, before losing to Dean Smith’s North Carolina team, 123-97, on a team that would have seven future NBA players, including J.R. Reid and Rick Fox, plus senior guards Jeff Lebo and Steve Bucknell.

In the 1988-89 season, Gathers was the only player in the country to top 1,000 points as he became just the second player ever to lead college basketball in scoring and rebounding. Kimble, reduced to 18 games and just 10 starts, averaged 16.8 points. The Lions were tied for second in the WCC during the regular season, 19-11 overall. Unranked, they had to capture the conference tournament and the automatic NCAA bid. LMU then lost to Nolan Richardson’s Southwest Conference-champion Arkansas team in the first round of the NCAA tournament by 19 points.

The 1989-90 season would start for Loyola Marymount with a loss at UNLV, 102-91. The Runnin’ Rebels were ranked No. 1.

That season would end with another LMU loss to UNLV, 131-101. The Runnin’ Rebels were then ranked No. 2.

The 30 games that happened in between that for the Lions was as wild a roller coaster ride that a Hollywood scriptwriter couldn’t even dream up.

On Dec. 7, the fifth game of the season, Gathers had 37 points and 27 rebounds as LMU put up a 152-137 win at U.S. International in San Diego. This was all intentional. The programs had met before and set off fireworks, and this was a game billed as LMU’s shot to be the first college team to put up a 200-point game. The marquee here even predicted: “History in the Making.”

The combined score was only the fourth highest in NCAA Division I history — three of those four games were LMU-USIU contests. The record remained LMU’s 181-150 win over USIU in January 1989, a game in which Gathers had 41 points and 29 rebounds.

“I think (a record) was on our mind, but my guys didn’t really have that 200 look on their faces,” Gathers said. “USIU did a good job of smacking us and making us wake up.”

Two days later, on Dec. 9, Gathers fainted during a 104-101 home win against UC Santa Barbara. He was hospitalized with an irregular heart beat. It was diagnosed as an exercise-induced heart abnormality. Gathers missed two games – a win at No. 21 Oregon State and a home loss to No. 7 Oklahoma. He returned on Dec. 30 after being prescribed the beta-blocking drug Inderal.

Gathers said the prescription made him feel sluggish. He successfully lobbied to get his dosage reduced.

Westhead had a program for his team to stay in shape by running the hill at Sand Dune Park in Manhattan Beach. The team would also run laps in the LMU swimming poll. They would do sprints with life vests. The preparation to eliminate fatigue was as important to their offensive scheme.

Perhaps the most memorable single game in the three seasons of the Kimble-Gathers partnership at LMU came on on Feb. 3, 1990. The N0. 20 Lions were already seven games into its WCC schedule but Westhead agreed to a national TV appearance at No. 16 Louisiana State, led by 17-year-old freshman Shaquille O’Neal and beefy 7-foot sophomore Stanley Roberts.

Dozens of NBA scouts who likely came to see O’Neal would also come away with a new impression of Gathers.

Gathers’ first five shots may have been blocked by O’Neal, but he ended up scoring 48 points on 35 shots to go with 13 rebounds. Kimble added 28 points and 11 rebounds.

“That’s the perfect example of the will and the tenacity and the unstoppable mindset that Hank had, that when I get this ball, nobody can guard me,” said Kimble. “He played with that presence that began his junior year in high school: In the paint, I’m unstoppable; I don’t care who you are.”

LSU won, 148-141, in overtime. The average time of possession was 9.7 seconds for LMU and 11.3 seconds for LSU. O’Neal had 20 points, 24 rebounds and 12 blocks in 32 minutes; Roberts had 21 points (on 10-of-10 shooting) with 12 rebounds, while guard Chris Jackson had 34 points.

Kimble added: “I played with Hank for 11 years, and there’s no better story about his heart and resilience than the LSU game. He said, ‘You did a great job blocking the first five shots, but good luck trying to stop the next 30.'”

That weekend, LMU actually played St. Mary’s on Thursday night in L.A. (a 150-119 win), flew to Baton Rouge at 7:10 a.m. Friday, practiced in the afternoon, played LSU at 1 p.m. Saturday, left immediately afterwards on a return flight to L.A., landed around midnight, and hosted San Francisco at 5 p.m. Sunday (a 157-115 win). The Lions scored 448 points in three games over a four-day stretch that included cross-country travel.

During that ’89-’90 season, Kimble had four games of 50 or more points. One of them was a 53-point explosion in a four-point win over Oregon State, where the Beavers’ defensive specialist, Gary Payton, scored 48 points himself but fouled out trying to “glove” Kimble.

Either Kimble or Gathers was the LMU top scorer in all but two games that season. Either Kimble or Gathers was the team’s leading rebounder in all those games.

The season also was set up so that Gathers and Kimble played two games in their native Philadelphia just before the start of the WCC season. Kimble hit a game-winning half-court shot to beat St. Joseph’s, 99-96. Two days later, LMU outran No. 17 LaSalle and Lionel Simmons, 121-116, overcoming a 34-point, 19-rebound performance by its All-American.

With a 22-5 record, LMU opened the WCC Tournament at on its home court, Gersten Pavilion. After putting away Gonzaga, 121-84, in the first round on a Saturday night, it faced Portland the next day.

As the Portland team practiced in the Lions’ gym on Saturday, sophomore point guard Erik Spoelstra said he noticed something.

“There are windows on one end of their gym,” said Spoelstra, who would go on to become the head coach of the NBA-champion Miami Heat. “On the other side of the windows, there’s a track. I’ll never forget, that day we saw Hank (Gathers) out there running sprints with a parachute on his back. To see the leading scorer and leading rebounder in the nation with that kind of work ethic, we were beaten before we even played.”

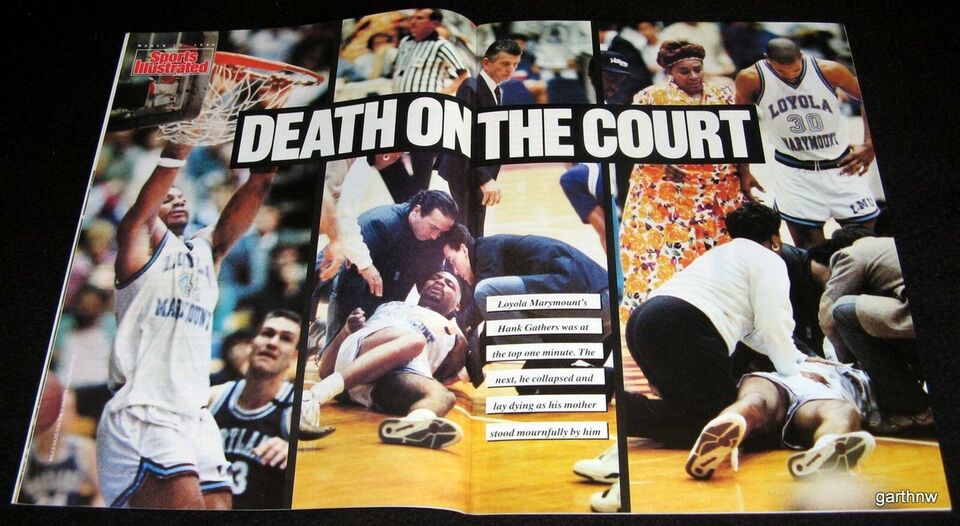

At 5:14 p.m., on Sunday March 4, 1990, Spoelstra was standing beneath the North basket when Gathers took a precision alley-oop pass from teammate Terrell Lowery and finished off a dunk. It gave LMU a 25-13 first-half lead.

“Great pass by Terrell Lowery,” said KXLU-FM radio analyst Brian Berger. “He was on the left side at half court. He threw it up. A perfect pass. Hank caught it in stride and jammed it! That brought the crowd to its feet.”

“Hank was right in position,” added play-by-play man, Keith Forman. “It wasn’t even a lob pass – he just rifled it up there. That’s got to be one of the quickest alley-opps …”

The crowd of 4,000 then gasped.

“Hank collapsed!” Berger reported.

Gathers started to run back up court to take his position in the full-court press.

He had a look of panic and fear on his face, staggered, fell and was became helpless near midcourt. He tried to turn on his knees to stand, and show everyone he was OK. His body wouldn’t help. He crumpled into the trainers’ arms. He started to convulse.

“Everything started moving in slow motion,” said Spoelstra. “There was a piercing silence in the gym. It was eerie.”

Gary Jones, the L.A. Daily News reporter courtside at the game, dialed 911 per instructions from LMU athletic director Brian Quinn, who raced from his seat to the court. LMU trainer Chip Schaefer would recall about seeing Gathers: “He was responsive and I tried to relax him while they were getting the stretcher and defibrillator. But then he got a different look on his face and his eyes shut.”

Gathers’ mother, Lucille, stood by Kimble and prayed with Hank’s aunt Carol and his brothers, Derrick and Charles, and his girlfriend Vernell.

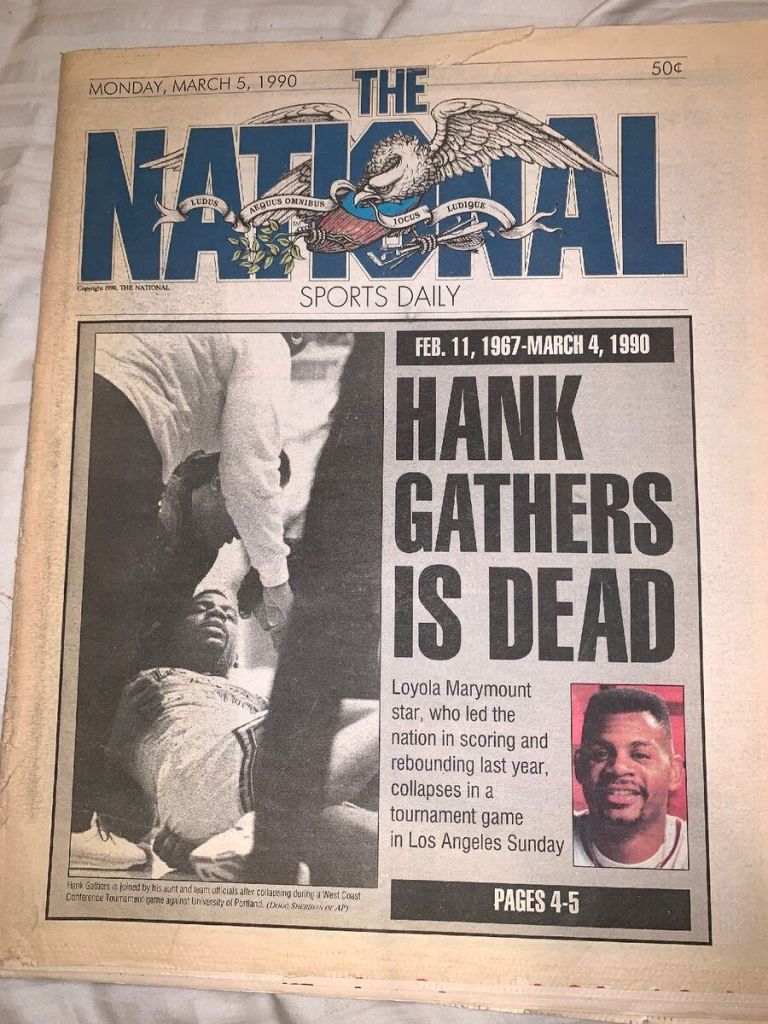

An hour and a half later at nearby Daniel Freeman Marina Hospital, Gathers died at age 23.

The game wasn’t on TV, and most of the city didn’t know about the news until Chick Hearn informed viewers on that Sunday night’s Lakers-Minnesota contest from the Forum.

The college basketball world was in shock. The WCC Tournament was cancelled. LMU was given the NCAA automatic tournament bid — if the players even wanted to keep playing.

Westhead told the team it was up to them if they wanted to continue.

“If someone had said the best way we could honor Hank was to pack it up and never play another game, I don’t think I would have objected,” Westhead would say. “The beauty of the players was that they never made it seem like a Hollywood script; they clearly felt as though it was their way of honoring Hank. They were sincere and straightforward.”

Kimble said he had the feeling that the entire ordeal was not real.

“We were playing with a stronger purpose,” he said.

Los Angeles Times editorial cartoonist Paul Conrad, who had attended the game and sat with Westhead’s wife, Cassie, ended up drawing an illustration to capture the moment — a basketball with a comet-like tail sailed across a dark sky. There was a line from the poem, “I Think Continually of Those Who Were Truly Great,” that accompanied it. “Born of the sun, he traveled a short while toward the sun and left the vivid air signed with his honor.”

L.A. Times columnist Jim Murray wrote: “Death should stay away from young men’s games. Death belongs in musty hospital rooms, sickbeds. It shouldn’t impinge its terrible presence on the celebration of youth, reap its frightful harvest on fields where cheers ring and bands play and banners wave.”

A memorial service was scheduled right in the middle of Easter season. It was moved from the small LMU chapel to the larger Gersten Pavilion arena, and the banners went up: “Hank’s House.”

“Every time I pick up a basketball for the rest of my life, Hank Gathers will be with me,” said Kimble during a eulogy. “Hank, I love you so much. You are the world to me. You will never know how much you mean to a person until they are gone. But now I know.”

Another funeral Mass happened in Philadelphia days later, with Gathers’ teammates as his pallbearers.

The NCAA Tournament organizers were in tune with what was happening and arranged for LMU and its fans a best path to staying as close to home as possible.

As the No. 11 seed in the West Region, LMU would start play at the Long Beach Arena. Players wrote tributes on shoes, wristbands and anywhere else it could be seen. So did the fans.

“I can guarantee you I felt from the moment we laced up our shoes that we would be national champions,” Kimble said.

During a remarkable 111-92 win over No. 24 New Mexico State in the NCAA opener, Kimble, who picked up three early fouls and stayed in the game the whole way, paused to shoot his first free throw left handed. It was in memory of Gathers. Kimble cupped the ball in his left hand and seemed to launch it like a shot put. He made it.

He then made one right handed. LMU was up by 16.

The backstory — despite his ability to score from all over the court, Gathers’ reputation of being such a poor free-throw shooter led to him trying all sorts of new approaches. The latest one: He changed from shooting right handed to left handed to see if he could improve. When Gathers tried shooting left-handed during games, it looked awkward, but he kept trying to get better.

“The first one, against New Mexico State, that entire game I felt like I had the power and strength of Hank,” said Kimble years later. “It was like I swallowed a Superman pill. I ran faster and never got tired. All that pain and grief, I put on the floor.”

Kimble had 45 points and 18 rebounds in the win.

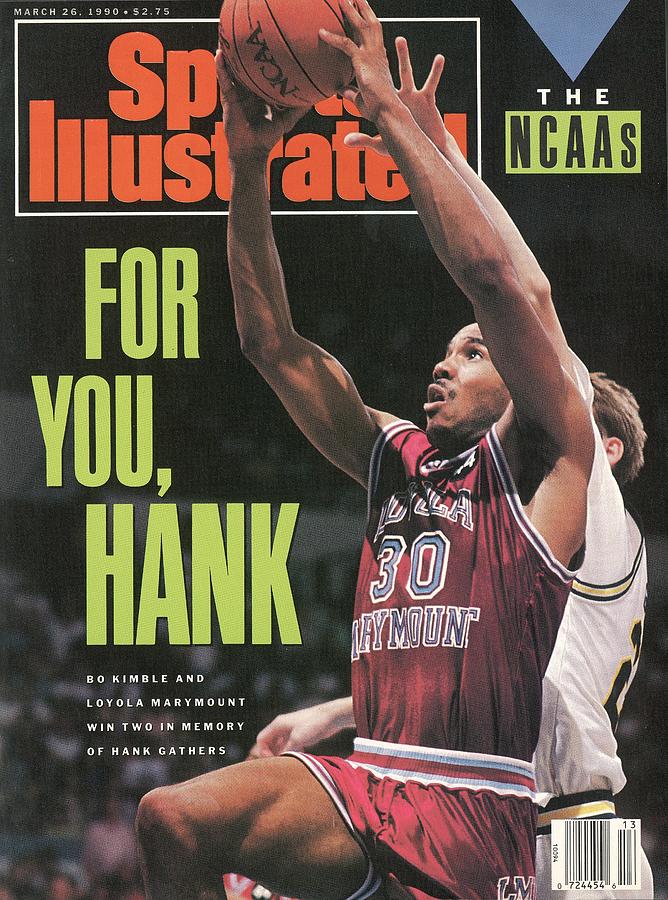

Two days later, LMU came up against defending champion Michigan, ranked No. 13 as the Big Ten champs and loaded with four future NBA first-round draft picks. LMU won 149-115. Kimble made another left-handed free throw. The crowds erupted. Kimble scored 37, and guard Jeff Fryer was 11-for-15 from 3-point range to set an NCAA tournament record while scoring 41. LMU broke the tournament single-game scoring record by 21 points.

The Sweet 16 shifted upstate to Oakland. On March 23, No. 23 Alabama slowed the pace — even pulling up on 3-on-1 scoring opportunities, but LMU still prevailed 62-60. Robert Horry, who would be known as “Big Shot Rob” in his NBA days for making clutch baskets, missed a shot for the Tide in the closing seconds that could have tied it. Kimble led the way with 19 points.

Two days later came the Elite Eight — how in their state of being could LMU even get this far? This UNLV team had Larry Johnson and Stacey Augman, and Jerry Tarkanian as the head coach.

Go back to that season-opening loss where the Lions opened the Preseason NIT game in Vegas against the Rebels back in November.

In the middle of the first half, there was a 20-minute delay because a bomb threat had been called in. It turned out to be a hoax. LMU was up 40-34. The Lions players thought that was pretty convenient as UNLV, showing signs of being run out of its own gym, could come back, slow the pace, take control and erase what was LMU’s two-point halftime lead. Gathers had a team-high 11 rebounds in that LMU loss. At game’s end there were no handshakes, and a fight between the two teams almost broke out in the tunnel that left both squads pointing, shoving and shouting all the way to their dressing rooms.

Hank Gathers had 18 points and 11 rebounds in the game. But this time, for the rematch, LMU had to continue on without him.

In LMU’s final game of the season, UNLV led by 20 at halftime before winning by 30, 131-101.

For the tournament, Kimble, who went 3-for-3 on left-handed free throws, scored 42 points.

“We were human,” said Westhead. “Reality caught up with us.”

When UNLV went on to win the NCAA title by 30 points over Duke, Rebels players wore a patch in Gathers’ honor.

The adrenaline rush was over. A lot of shining moments of grit and fortitude. The team didn’t win without Gathers. They won games for Gathers.

You can’t blame the Los Angeles Clippers for trying to capture some of that energy when, three months later, they made Kimble their No. 8 overall choice in the 1990 NBA draft. His selection was easy to market to the Southern California basketball fans base.

Back to wearing No. 30, Kimble would eventually sign a five-year, $7.25 million deal. One was left to wonder how Gathers would have fared in that draft, and what kind of contract he would have drawn.

In the Clippers’ Nov. 3 season-opening win over Sacramento at the L.A. Sports Arena — the place where Kimble and Gathers started their college careers at USC — Kimble scored 22 points and shot his first NBA free throw left-handed with 9:33 left in the third quarter.

This time, he missed it. He said he would not do that again.

Kimble only started 22 of 62 games as a rookie and averaged 6.9 points a game. His best effort was a 27-point game in a win over Minnesota at the Sports Arena in early December, 1990.

He played in half as many games his season year, never starting, at only eight minutes a game.

As part of a three-team trade with New York and Orlando that involved Doc Rivers, Charles Smith, Mark Jackson and Stanley Roberts, Kimble went back East, played only nine games for the Knicks, and it just wasn’t working. He was finished. The Knicks paid him the rest of his $3.45 million owed to him over three years there not to play.

The legacy

Paul Westhead’s tenure at LMU ended with that 1989-90 team, as he was offered the head coaching job with the NBA’s Denver Nuggets. Westhead said he needed closure.

In five seasons, he posted a 105-48 record overall at LMU — 51-19 in conference and 37-5 over the last three seasons with Gathers and Kimble. With that came two regular-season conference titles, three NCAA Tournament appearances and one NIT bid.

What may not be remembered is that the year after he was let go by the Lakers, Westhead was encouraged to start a basketball program at Marymount College, a small private institution in Palos Verdes. The campus’ basketball court consisted of one hoop at the end of the parking lot. Westhead recruited eight students to play. He even got the campus gardener to enlist his son. They played at a rec center in San Pedro but couldn’t schedule any games.

“That was my one and only undefeated season,” Westhead wrote in a 2020 book about his experiences as a coach, “The Speed Game: My Fast Times in Basketball.”

Still, it helped him get the LMU job. The Gersten Pavilion home court was familiar — it was where his Lakers teams often had their practices.

Westhead’s book included this assessment of his philosophy:

“Former NBA coach Alex Hannum called my system ‘crapadoodle.’ Who in their right mind would demand players sprint on every offensive possession and then defend full court on every defensive possession? It smacks of madness or, more accurately, stupidity. … Yet there is a stroke of genius in the scheme of press and run, press and run the entire game. The pace of the game will wear out the opponent no matter how superior the talent …When the players buy into the speed game, it is art in motion. It is genius. Whey they don’t buy in, usually because it is too hard, it is chaos. It is stupid. In my coaching career, I choose to walk the fine line between genius and stupid. Most of my coaching jobs, I looked stupid. But every once in awhile, like at LMU with Hank Gathers and Bo Kimble, I looked like a genius. The risk was worth the fleeting moment of pure speed. … My decision to recruit Bo Kimble and Hank Gathers changed LMU and my coaching career forever … Bo and Hank made my career … I was the bandleader along for the ride, a very fast ride.“

Westhead, who still felt the speed game could work on the NBA level, couldn’t make it happen in Denver. His teams were 44-120.

Twice more he had pro head coach jobs in Los Angeles. First was with the Los Angeles Stars of the revived ABA in 2000-01. Borrowing the name of the ABA team once part of the city decades earlier, Westhead’s team included Ed O’Bannon, Toby Bailey and Scott Brooks, and played its games at the Great Western Forum in Inglewood — after the Lakers had just moved to the downtown Staples Center. The Stars finished 28-13 but lost in the first round of the playoffs. The team folded.

Westhead came back to coach the new ABA’s Long Beach Jam in 2003. He lasted only one game before his agent alerted him about an assistant job with the NBA’s Orlando Magic, where he could try his system again. The Magic players didn’t buy in.

Westhead would give his system a try with the women’s game — he produced a WNBA title team in Phoenix in 2007, which gave him the unique distinction of having a championship with the top men’s and women’s pro leagues. Who else has done that? No one. Maybe that can be on his Basketball Hall of Fame plaque someday in Springfield, Mass.

When Westhead headed up the women’s program at the University of Oregon, he said he took a recording of the LMU-LSU game along with him to Eugene, Oregon.

“When I’m not in a happy mood,” he once told Sports Illustrated, “I’ll pick up that tape and revel in the mood of that day.”

As a player, Westhead came off the bench for Jack Ramsay’s St. Joseph’s team that made it the 1961 Final Four. That team lost to Jerry Lucas’ Ohio State squad, but it won the third-place game against Utah in four overtimes. The St. Joe’s Hawks’ 127–120 over the Utah Redskins set a record for the highest-scoring NCAA Tournament game that lasted nearly 30 years — until LMU’s win over Michigan in the second round of the ’90 tournament. But that also exposed Westhead to his first NCAA Tournament heartbreak — St. Joe’s had to vacate that win vacated because the NCAA found three of its players were implicated in a season-long point-shaving scandal, later banned from the NBA.

After earning a Masters in English Lit at Villanova, Westhead was head of the English department at Dayton when he was convinced to be a volunteer assistant for its basketball team. His coaching career would span six decades from 1969 to 2014 — 23 years in college, 13 years in the NBA, several years overseas, all after starting in high school.

In the cycle of basketball life, Westhead had the unique opportunity to see his grandson play basketball at Loyola High in Los Angeles on a team that included Aaron Crump, the son of Hank Gathers.

Crump, who was 6 at the time of Gathers’ death, was born when his father was 16 and still in high school. The merging of the Westhead and Gathers families on the basketball court was particularity poignant after lawsuits had been filed and out-of-court settlements occurred over who was deemed legally responsible for the cause of Gathers’ death. Emotions had got in the way of healing.

As a high school senior, Crump was a starting point guard at Cheltenham High School just outside of Philadelphia, wearing No. 44 in honor of his father. Upon turning 18, Crump received $1.5 million from settlements tied to his father’s death. He said he bought a house, a Cadillac Escalade and had no plan for his future.

In 2007, Crump went to Rockview State Prison in Bellefonte, Penn., serving a five-year sentence for aggravated assault with a weapon, shooting a drug dealer in the back. When Crump was released from prison in 2012, he said the money he received from from legal settlements tied to Gathers’ death had been squandered.

Three years after their final college season together, Kimble authored a book, “For You Hank: The Story of Hank Gathers and Bo Kimble.”

An excerpt from the prologue: “I can still see him jumping for the basket, Terrell’s pass high over everyone’s head. Hank is there for it, seven, eight, nine feet tall. His muscular black arms reach up as he grabs the ball. His wrists cock back, ready. Then he explodes into action, his hands, wrists and arms driving the ball. He tosses it overhead into the hole. Yes! The Bank! The Beast! … Then he falls. Just like that. … It was like gravity took him, sideways and down. It was like he had been thrown out of a window … My mind was on two tracks. When I saw him sit up, I thought, ‘Whatever it is, he’s OK.’ At almost the same second, I had this other thought: ‘He’s already dead’.” … (The chaos of the situation) seemed to touch off fear in the crowd … I should have gone directly to the locker room, but somehow I couldn’t. Something in my body froze me. … Walking down the hallway, I saw a janitor’s closet. I opened it, stepped inside and closed myself in the darkness.”

Kimble also saw the release of a 1992 film titled “Final Shot: The Hank Gathers Story,” which helped tell the story of their earlier days influenced in Philadelphia by Fr. Dave Hagan and growing up in the projects.

In 2010, “The Heart of a Lion: The Life, Death and Legacy of Hank Gathers” by Kyle Kiederling came out. It took its title from a quote Gathers gave during that 1990 “Today” show interview with Gumbel: “I have a heart the size of a lion. I’m just going to go in there and be competitive and score points any way they come.”

Kimble wrote in the forward of that book: “When (Hank) and I first met on the playgrounds of north Philadelphia, we shared a passion for basketball. We both recognized that our only chance to escape the poverty that surrounded us each day was to be as good at basketball as we possibly could. We were both fierce competitors. … It was Hank’s incredible determination to get better than me that made him a great basketball player. … We matured as players and as human beings (at LMU). … When Hank died during our final season at LMU, I felt like a part of me died too. I didn’t know how I could go on without him. Father Dave and I decided that I would pay tribute to Hank by taking my first free throw left-handed to honor Hank’s memory. It never occurred to me that it would have such a huge impact on people. … I am still convinced that, had Hank lived, we would have become national champions. Our Elite Eight appearance may have been our greatest achievement, our own national title in honor of Hank. Hank and I will be forever joined together. I am honored that my name and his are mentioned together.”

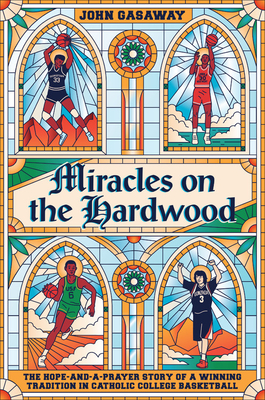

LMU’s incredible run — dare we call it miraculous? — is also documented in a chapter in the 2021 book, “Miracles on the Hardwood: The Hope-And-A-Prayer Story of a Winning Tradition in Catholic College Basketball,” by John Gasaway. The illustration on the cover, paying homage to the church’s tradition of stained glass windows, includes a depiction of Kimble taking his left-handed free throw in Gathers’ memory during the NCAA Tournament.

The pace of the LMU games was referenced in the chapter in how he placed “a particular burden on official scorers, expected to record every shot attempt, block and turnover for posterity.”

It concluded: “The records left behind by that season and by the area era are in the literal sense incredible, meaning that the numbers are not credible, not to be believed. Yet they are true. … It’s tempting to classify Loyola Marymount’s season scoring average of 122.4 as one of the proverbial records that will never be broken …Yet points per basketball game is a curious quantity, a performance measure that captures style and preference as much as it does achievement. Westhead’s style and preference in 1990 were what has come to be known as ‘the system,’ and a team that wants to set scoring records would be well-advised to use that system, or something like it. Kimble, in his 50s, would reportedly seek head coaching jobs at the collegiate level so that he could help teams do just that. Nevertheless, the system remains far more celebrated and chronicled than used … The system thrived with two players the caliber of Gathers and Kimble.”

Ten years after their final game together and the unforgettable run that followed, Kimble’s No. 30 and Gathers’ No. 44 were retired in a ceremony at LMU.

The two players individually, as well as the 1989-90 team collectively, were also inducted into the school’s Athletic Hall of Fame in 2005.

On the occasion of the 30th year anniversary of Gathers’ death, Kimble was asked what he thought might have happened if Hank stayed alive.

“There’s no question he’d be in the comedy clubs,” said Kimble. “He just had a knack for it. If you see Dave Chappelle today, that’s who Hank Gathers was.”

Kimble added: “I think about Hank every day. I’ve been in 53 countries. In every one of them, someone has asked me about Hank …

“Grown men will tell me, ‘Man, what you did when you shot those (left-handed) free throws, it made me cry. People love Hank Gathers. They won’t allow us to forget him.”

Westhead once said he thought Gathers’ would have enjoyed an NBA career of maybe a dozen years averaging 15 points and 10 rebounds a game.

In 2011, Kimble helped start the non-profit The 44 For Life Foundation. It came up as Kimble was playing in a summer basketball league at a YMCA in New Jersey when a 38-year-old player named Robert Carter collapsed on the court and died — just as Gathers once did.

“It was extremely bizarre,” Kimble said. “I didn’t know his name, but I did know his face. He was a very competitive athlete. When he went down, I was one of three people that was fanning him with a towel.”

The paramedics arrived within five minutes and tried resuscitating him. They weren’t in time.

“I didn’t know first-aid; I didn’t know CPR,” said Kimble. “He didn’t need us fanning him with a towel. He needed somebody to perform CPR.”

The program encourages kids 22 and younger to come to the Hank Gathers Center in Philadelphia for echocardiogram and electrocardiogram screenings.

Just weeks prior to the COVID pandemic of 2020, a statue of Gathers went up outside of Gersten Pavilion, marking 30 years after his death. It depicts Gathers at the point of takeoff, about to slam dunk, his jersey rippling from the ferocious hallmarks of his game: Speed and power. Lucille Gathers was at the dedication, accepting and giving as many hugs as anyone present.

The photos may have faded, but memories remain strong when there is a reason to summons the Kimble-Gathers relationship decades later.

When Miami Heat star Chris Bosh was trying decide if he should keep playing in the NBA despite doctors finding troubling blood clots in 2016, Kimble was one of several who urged him to retire. Bosh did in 2019.

When Buffalo Bills defensive back Damar Hamlin collapsed during a nationally televised Monday Night Football game at Cincinnati in January of 2023, the stadium went silent and all feared the worse. At 24, Hamlin was just one year older than Gathers when he died. Hamlin survived because the medical and training staffs did CPR for 10 minutes before Hamlin was taken to an area hospital.

“They did exactly what we learned from the Hank experience — you do the CPR immediately,” said Kimble. “That’s a perfect response. Hank’s death was not in vain.”

In July of 2023, when 18-year-old USC guard Bronny James collapsed on the court and went into cardiac arrest during a practice session, the protocol put into place because of Gathers’ death decades earlier likely saved him.

Cardiac events are still considered rare among college athletes — one in every 50,000 will experience it, the experts say. But drilling down more, the rate among men’s basketball players is one in 9,000. Male athletes suffer cardiac events about three times as often as female ones, Black athletes are most at risk than athletes of other races.

The eldest son of Shaquille O’Neal discovered weeks before the start of his freshman season at UCLA he was born with an anomalous coronary artery, a condition that only increases the risk of sudden cardiac arrest if it goes unfixed. UCLA cleared Shareef O’Neal to play again in 2019 after the 18-year-old underwent open-heart surgery to repair the abnormality.

The halo affect of Gathers’ case is that coaches know CPR, there is the required presence of defibrillators in the arenas and gyms, and more emergency medical services available.

Kimble once told the Philadelphia Inquirer: “We buy expensive cars. We buy expensive jewelry. We take vacations. We buy houses. We do all these flamboyant things in life, but we don’t buy defibrillators and have them at home or at the workplace. If you can’t afford it, learn CPR. There’s a lot of things that we don’t do for ourselves but we’ll do anything for our children. So what I say to parents is that it’s unacceptable to have a child — any age, but particularly a minor — and not know CPR. It’s unacceptable. Do it for your kids. Do it for your loved ones.

“You never know whose life you might have to save.”

Who else wore No. 30 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

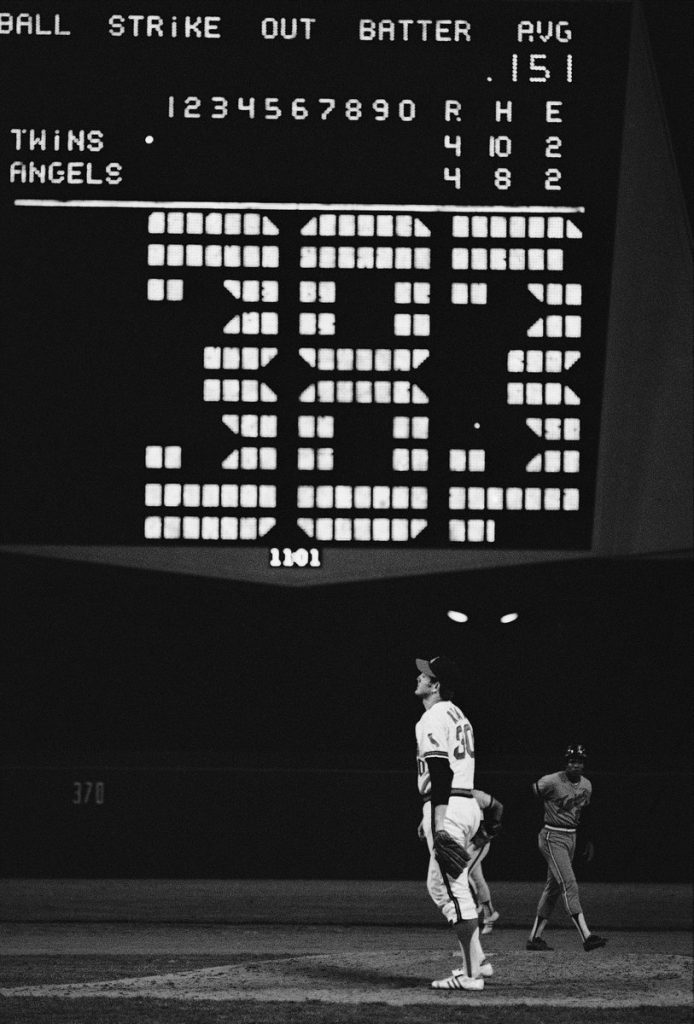

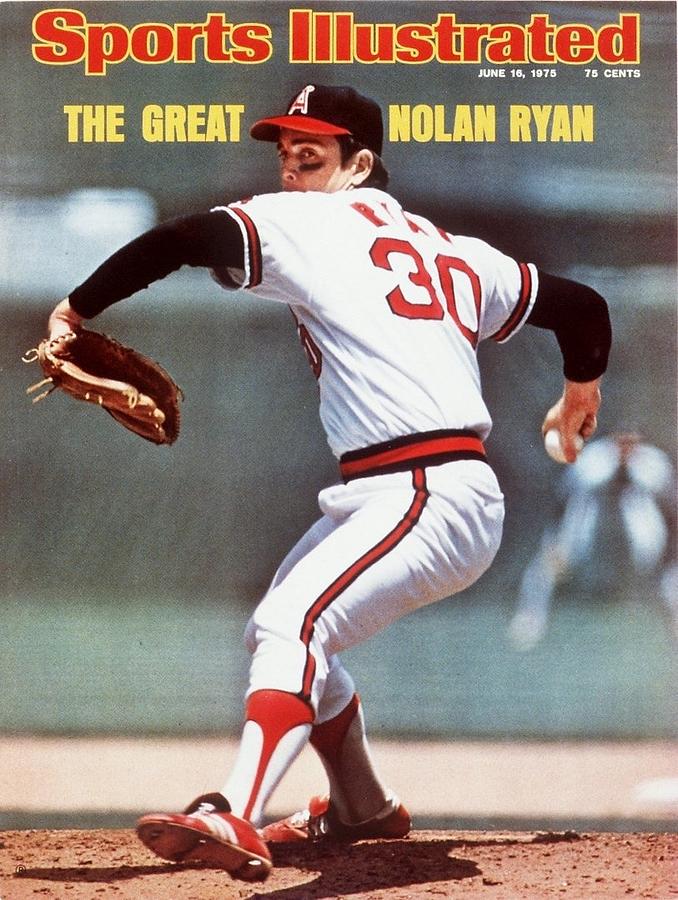

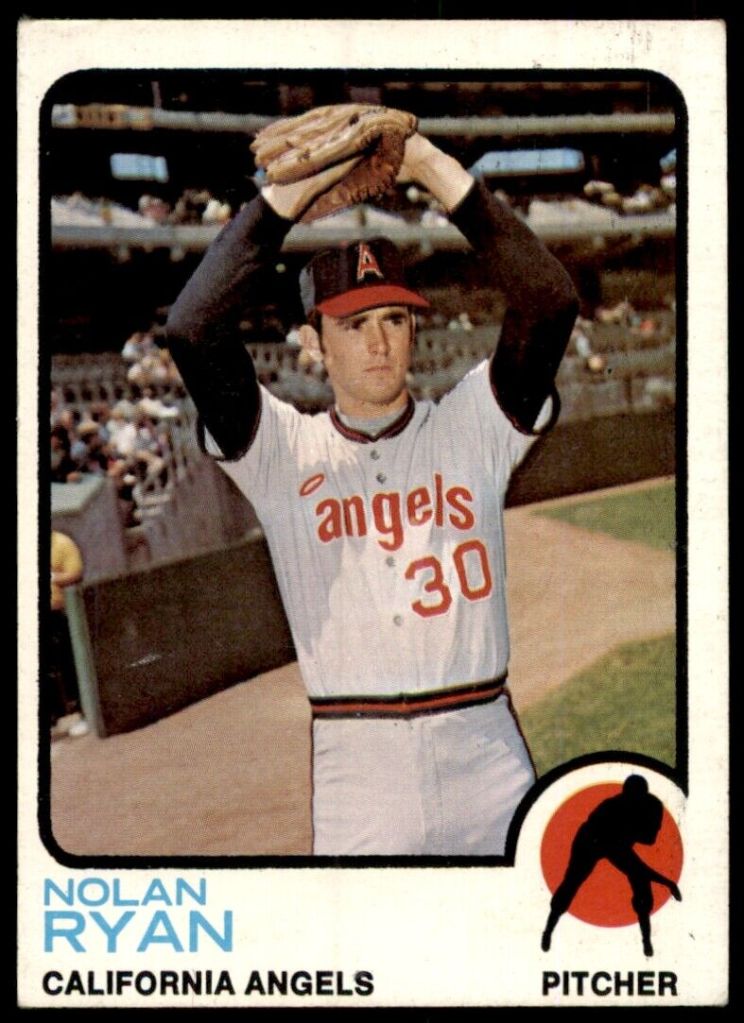

Nolan Ryan, California Angels pitcher (1972 to 1979):

Cy Young and Nolan Ryan rank Nos. 1 and 2 in the MLB all-time list of games started by a pitcher — Young: 815; Ryan: 773. And neither won a Cy Young Award. Go explain that.

Ryan, the powerball champ from Alvin, Tex., who wore menacing eye black and delivered a mythical maniacal fastball — was it really 108 mph? — had 27 seasons of various Cy Young-type seasons to pick from, including the eight he spent in Anaheim during the Angels’ version of “That ’70s Show” sit-com.

== 1972, his first year out West after five seasons with the Mets, making his first AL All Star team at age 25, racking up 19 wins, a league-high nine shutouts, striking out a league-best 329 with an 2.28 ERA. Yet Ryan was eighth, and last, in the voting behind winner Gaylord Perry of Cleveland.

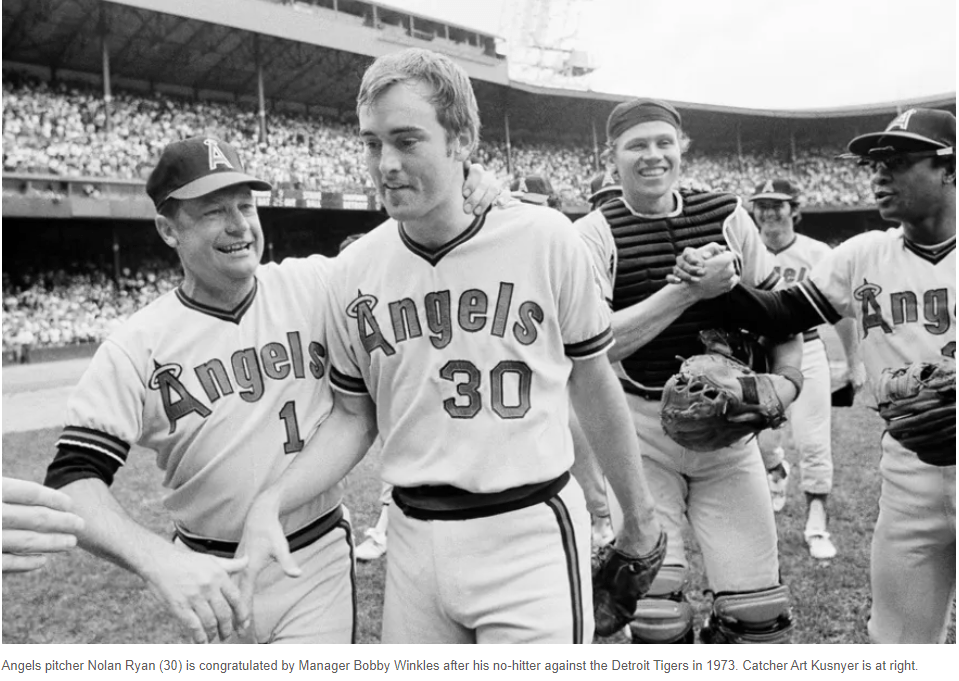

== 1973, when Ryan, having thrown two no-hitters, accumulated 21 wins, competed 26 games and went 11 innings of a tie game in his last start of the season to get his 17th strikeout that broke Sandy Koufax’ single-season MLB record of 383 Ks. Was this one of the single-most dominant seasons ever in MLB history? According to this, it wasn’t even the most dominant in Angels’ history — it happened a decade earlier, when an Angels pitcher actually did win a Cy Young, at a time when it was just one for the entire game). Instead, the award went to Jim Palmer (22-9. 2.40), from a team that won 97 games, while the Angels were just 79-85. Meaning Ryan was responsible for more than one-fourth of his team’s victories.

== 1974, when Ryan posted a career-best 22 wins with a league-high 332 2/3 innings pitched (also a career high), 26 more complete games, another no hitter (walking eight and striking out 15 against Minnesota), and another strike-out title with 367. He was third behind Catfish Hunter and Fergie Jenkins, who both won 25 games. The Angels had an AL-worst 68-94 record, 22 games out in the West behind Hunter’s A’s and Jenkins’ Rangers.

== 1975, despite his MLB-record-tying fourth no hitter, and another All-Star appearance, he wasn’t even in the top eight (while teammate Frank Tanana was tied for fourth, having led the AL in strike outs).

(Maybe that year Ryan was too wrapped up in securing a 1975 Daytime Emmy Award for playing himself on three episodes of the ABC soap opera, “Ryan’s Hope.” He was robbed there, too.)

== 1977, when Ryan won 19, tied Palmer with 22 complete games, another league-best 341 strike outs and his fourth All Star appearance. Ryan lagged in third behind Yankees relief pitcher Sparky Lyle and Palmer.

What the baseball writers who had ballots didn’t want to overlook in all those years was a) the Angels weren’t always in contention and b) Ryan led the AL in walks six times in that period, and three times in wild pitches. In ’76, he also paired 17 wins with a league-worst 18 losses despite a 3.36 ERA and a league-best seven shutouts.

After departing Anaheim, Ryan would sniff a couple more Cy Young Award votes – ninth place in ’83 with Houston (because one guy gave him one vote), fifth place in ’87 with Houston (when he led the entire MLB with a 2.76 ERA and 270 strikeouts, but was 8-16), and fifth place in ’89 with Texas, when he topped the sport with 301 Ks.

The Cy Young Award is named after someone who kinda reminds us of Ryan.

Cy Young not only amassed a major-league record of 511 wins in 22 seasons, but also 315 losses. He pitched for five teams between 1890 and 1911. It wasn’t until Cy Young’s death in 1955 that baseball was inspired to create the award, first given out in ’56 to the best pitcher in the entire game. But after awhile, Sandy Koufax, whom Ryan idolized, won it in ’63, ’65 and ’66, and it was decided to have one for both the NL and AL starting in ’67.

So in one regard, Ryan is in the forever Cy-winless status with Walter Johnson, Grover Cleveland Alexander, Christy Mathewson, and Bob Feller. And Cy Young. Because that honor wasn’t around for those five Hall of Famers. Yet there are master craftsmen like Juan Marichal, Don Sutton, Phil Niekro, Mike Mussina and Bert Blyleven – all in the Hall of Fame — who never captured a Cy. Different eras. Different sets of stats to impress voters.

(It can also work the freakish opposite way: While Ryan threw seven no-hitters but never won a Cy Young, Roger Clemens won seven Cy Youngs but never threw a no-hitter. Who’s in the Hall of Fame now?)

So here’s the point: If you had the option to take any one of those pitchers above as the one you needed in the toughest situation of a season, the grittiest, nastiest guy who’d likely kill a Robin with a rock to the head if he had to, who’d you pick?

To write as close as possible the consummate biography on the life and times of Lynn Nolan Ryan Jr., Rob Goldman had to first check what he already had embedded in his memory.

As a bat boy for the Angels in the mid-1970s when his Palisades High teachers would let him leave class a little early to drive to Anaheim, Goldman lived through some of Ryan’s most historic moments — two of his four no-hitters with the team and the season where Ryan set the single-season strike out mark.

Goldman’s foundation along with his journalistic pursuit of context launched a 2014 text, “Nolan Ryan: The Making of a Pitcher.” Ryan’s work ethic as the youngest of six kids whose father worked two jobs during the Depression was his foundation.

“He knew what poor was,” Goldman told us when the book came out. “His family was always on the brink of disaster. Work was a privilege for the Ryans when the sun came up. They felt it was God’s gift to work. So he took that into the baseball realm and became one of a kind.”

Ryan’s most admired quality, as far as Goldman was concerned: Humility.

“He didn’t need to be in the spotlight. It’s the same with John Wooden, Vin Scully, Lou Gehrig … they have all the qualities of humility, family, curiosity, work ethic, humor. They don’t feel like they deserve the fame because they’re just being themselves.

“Don’t get me wrong, when Nolan stepped on the field, all that was tossed out. It was war. He really wasn’t a pleasant guy when he pitched. He swore, and kicked things, he threw at people. But he also was always drawn to the smartest guys in the clubhouse. He didn’t succeed alone.

“He had help and great conditioning minds in the clubhouse at the same time. He had enough humility and curiosity to listen to these people. That’s where his strength was. He was open and let new information in. He never was too big for his britches.”

The Ryan family relocation to Anaheim came as no surprise after the 1971 season as he sensed he was no longer part of the long-term plans of the New York Mets’ plans, even as he earned a key save in Game 3 of the 1969 World Series. He was just too inconsistent.

In the 2022 documentary “Facing Nolan,” Ryan explains how in December of that year he got a call from Mets GM Bob Scheffing, telling him he “was going to sunny California.”

“I thought, all right,” said Ryan. “I’m gonna be a Dodger.”

Then Scheffing told him that he was one of four Mets (including Lee Stanton, Don Rose and Frank Estrada) going to the California Angels in exchange for their team captain/shortstop Jim Fregosi.

“I mean, I coulda died,” Ryan added.

The saving grace was that Ryan was a fan of Gene Autry, the Angels owner and better known as the movie’s singing cowboy.

“He was a big deal,” Ryan said of Autry.

In Joe Posnanski’s book, “The Baseball 100,” Nolan Ryan sits right smack in the middle of the Top 100. Posnanski wrote this to the start of the entry, which first appeared in The Athletic in 2020:

Nolan Ryan was the greatest pitcher who ever lived. Nolan Ryan was the most frustrating pitcher who ever lived. … He was unbeatable. Nobody in modern baseball lost more. It is as if Ryan is not actually a pitcher but something else entirely — an alien, a cartoon character, a folk hero, a saxophone. Trying to find a place for Ryan on a list like this is like trying to figure out where the Beatles belong on your list of favorite pastas. … (Ryan) is incomparable. Anything a pitcher can do, he did better. Anything a pitcher can do, he did worse. There’s nobody else in this category.

Meanwhile, Ryan’s biography for the Society of American Baseball Research starts like this: His dominance on the mound makes him head and shoulders above almost any other pitcher since 1970. His longevity — winning a strikeout crown and throwing a no-hitter while being the oldest player in the game at the age of 43 — makes him the stuff of legend.

In 1979, the 32-year-old Ryan started with a 12-6 record and was the AL starting pitcher in Seattle at the All Star Game. It came in the halo effect that just a few days after he nearly threw his fifth no hitter — enough to warrant another Sports Illustrated cover — going eight no-hit innings against the New York Yankees at Angel Stadium only to have Reggie Jackson break it up with one out in the ninth and ruin the shutout as well.

Ryan’s second half kind of derailed as he made a trip to the DL with a sore elbow — bone chips it would turn out — and grind out a 16-14 record. He still had a league-best five shutouts and 223 strikeouts.

He was making $200,000 at the end of a three-year, $600,000 deal.

Angels GM Buzzie Bavasi, whose team just posted 88 wins and won the AL West, had the famous quote when asked about signing Ryan as entered free-agent status: “All I need to replace Ryan is have two 8-7 pitchers.”

Ryan biographer Goldman could see Bavasi’s logic. He noted in the book that Ryan “had thrown more than 56,000 pitches and basically re-written the record book for power pitcher. But for all that, the Angels had played just one season of .500 ball.” Yet, Ryan’s W-L record of .533 was better than the team’s .481 mark over that time.

Ryan and his wife also had new priorities. Living in New York or Southern California wasn’t all that. In ’79, their oldest son, Reid, had been hit by a car outside their Villa Park home while Ryan was on an Angels’ road trip in Boston. It made the family homesick.

Ryan’s agent, Dick Moss, asked the Angels for $550,000. When Bavasi balked, Moss got Ryan a three-year, $3 million deal with Houston, with another $1 million option year, plus a $250,000 signing bonus.

Welcome to the wild, wild 1980s.Ryan became not just the first $1 million a year player in baseball, but in all of sports. It opened the door for free agents behind him.

Nice salary bump for someone who made $7,000 in his first year with the Mets.

With Ryan gone in 1980, the Angels dropped to sixth in the AL West (65-90). And how did Bavasi do on his hope without Ryan? Their top free agent pitcher signing in ’80 was Bruce Kison, who went 3-6. They picked up Ed Halicki off waivers at mid-season after he was let go by San Francisco. The Angels released him a few months later. Eight of the Angels’ pitchers who made at least seven starts that year had sub-.500 records.

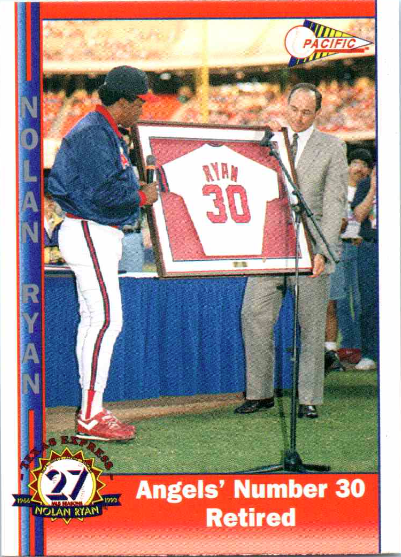

In 1981, Bavasi brought in Geoff Zahn (10-11), Ken Forsch (11-7) and Steve Renko (8-4). Zahn eventually was an 18-game winner. In ’82, Bavasi signed Dodgers’ reject Dave Goltz (8-5), and even gave him Ryan’s No. 30. For that matter, after Ryan left, the Angels gave No. 30 to players such as Tom Brunansky (1981), Dick Schofield (’83 to ’84), Derrell Thomas (’84), Devon White (’86 to ’90) and Auben Amaro Jr. (’91).

Ryan pitched 14 more seasons and posted 158 more wins after leaving Anaheim. He went 11-10 with a 3.35 ERA that first season in Houston. The second year, he made the NL All Star team, posted a league best 1.69 ERA in 21 starts.

Cy Young wasn’t even among the first group put into the Hall of Fame. Even though the place opened in 1939, voting began in ’36, and it was allowed to put 10 players up for induction as long as they got 75 percent. Young was in eighth place, not even reaching 50 percent. In ’37, he got barely enough (76.1 percent) and was included in the first group photo of inductees a couple years later.

Ryan, meanwhile, got in on his first try in 1999 with 491 of the 497 votes (98.8 percent).

Ryan remains the Angels’ franchise leader in strikeouts (2,416), shutouts (40), walks (1,302) and complete games (156), second in bWAR for pitchers (40.0), innings pitched (2,181) and strikeouts per nine innings (9.96), third in wins (138) and games started (288) and fourth in ERA (3.07). In addition to his four no hitters with the Angels, he also had five one-hitters, 13 two-hitters and 19 three hitters.

He holds more than 50 MLB records, not just for the seven career no-hitters, but also 12 one-hitters, 18 two-hitters and 31 three-hitters. For most strikeouts (5,714, almost 1,000 more than the No. 2 leader, Randy Johnson. For most walks (2,795, almost 1,000 more the No. 2 victim, Steve Carlton).

Also for most seasons as a pitcher (27).

Ryan lasted so long as a player, the Angels retired his No. 30 in 1992, when, at age 45, while he was still pitching his last 40-some games for the Texas Rangers. The Rangers and Astros have also retired No. 34 for him. No. 30 is what Ryan carried over to Anaheim from his last three seasons wearing with the Mets, after coming up as a 19-year-old rookie in 1966 wearing No. 34.

When Ryan retired in ’93, it was because he blew out his ulnar lateral ligament in his right elbow. He could have had Tommy John surgery. But he didn’t want to chance it.

According to Goldman’s book, when Ryan finished logging his nine years with Houston and had an offer to return to the Angels in 1989, franchise owner Gene Autry was desperate to reverse Bavasi’s blunder and make sure Ryan entered the Hall of Fame as an Angel.

Goldman writes: “Jackie Autry, Gene’s wife, was on the phone constantly pleading the Angels’ case.” Jackie Autry told the Ryans that the Angels would top any free agent offer. Nolan’s wife, Ruth, didn’t want to uproot her family again. So they stayed in Texas. He slid over to the AL’s Rangers, and that is the logo he picked for his Hall of Fame plaque.

Maury Wills, Los Angeles Dodgers shortstop (1959 to 1966, 1969 to 1972):

The 1962 NL MVP set a modern-day record that season with 104 stolen bases (only caught 13 times), playing in all 165 games (including three tie-breakers to extend the season), with an NL-best 10 triples, a Gold Glove and one hit short of a .300 average.

He probably also stole that MVP award from San Francisco’s Willie Mays (NL-best 49 homers, 141 RBIs, .304 average). But it was the height of when the 5-foot-11 “Mouse That Roared” was showing how speed could be used as an important element of the game. He would lead the league in steals six years in a row, including 94 in ’65. That set the template for how the Dodgers’ somewhat insufficient offense would operate in the most efficient way to support a superior pitching staff.

“In 1965 I was 40 games ahead of my record-setting base-stealing pace of three years earlier, but my leg started bleeding internally,” Wills once admitted. “I had to stop stealing bases in August, I’ve always though that I had not been stopped by a recurrence of the hemorrhaging, I could have stolen 140 or even 150 bases that year.”

As the Los Angeles Times’ Bill Dwyre wrote in 2012, about 50 years after Wills’ MVP year: In a game against the Cubs at Wrigley Field, Wills took off for second base and, as the ball was flying over the mound, he heard the umpire’s call. ” ‘Safe,’ said Jocko Conlan. The Cubs protested, saying Conlan made the call well before the ball had even arrived at second base. To which Conlan replied, ‘You ain’t got him all year. Why would you think you’d get him this time?'”

A few things may have impinged on Wills’ case for Baseball Hall of Fame status – he was banished from the Dodgers from 1967 through early in the ’69 season after he upset some people in the front office with his off-the-field relationships. It also took him nearly eight years in the minor leagues before he started a 14-season career at age 26, finally breaking into the Dodgers’ lineup that had Pee Wee Reese at shortstop upon its move to L.A. By the time he finished – he went into managing, had drug issues, came back into coaching with the Dodgers –Wills amassed 586 steals that were ninth all time then, but is now 20th. Wills still set the table for lead off men like Hall of Famers Rickey Henderson and Tim Raines, as well as Vince Coleman, Willie Wilson, Bert Campaneris, Kenny Lofton, Otis Nixon and Juan Pierre (all ahead of him on the stolen base career list).

It is somewhat surprising he only posted a 39.6 career WAR while amassing 2,134 hits and scoring 1,067 times, playing in seven All Star Games, and the Dodgers’ spark in three World Series title runs in L.A. of ’59, ’63 and ’65. He even gained sixth place in the 1971 NL MVP voting, at age 38 (when he had just 15 steals, and Lou Brock, who led the league with 64 and 126 runs, was in the 13trh place).

One of the more quirky sidenotes to Wills’ career was how Topps didn’t issue a card of him until 1967 — he had already been in the league eight seasons with the Dodgers, and ’67 was his first year with Pittsburgh. In the book, “The Great American Baseball Card Flipping, Trading and Bubble Gum Book” (1973, Sports Illustrated Books/Little, Brown and Company), it was explained by Seymour Berger, head of Topps Chewing Gum Sports Department, that when the company started it intended to sign up every minor league player no matter how good or bad. That was cumbersome, so they hired a scout — Turk Karam, in the Dodgers organization — who went to the minor leagues to advise them on how to be more selective and only sign legit prospects to the Topps contract. And do it early. For a $1 fee. Maybe $5. On the cheap.

“Then one year, there was this very ordinary looking shortstop in the Dodgers organization — somewhere in the low minors — a real scrawny kid, nothing memorable about him at all,” Berger says in the book. “And everybody says — this kid will never make it. He can’t hit. He’s too small. Got bad hands. A weak arm. Forget about him. The guys in his own organization said this. And so we didn’t sign him, and of course it was Maury Wills.

“Well, Maury stayed angry at us for quite some time after that … even after he made it to the majors. He didn’t sign up with us until about his eighth year. He was the only major leaguer we didn’t have under contract. You couldn’t blame him of course. So after that we went back to signing everybody in the minors.”

For the first eight years, Wills’ image appeared on cards for Fleer, Post Cereal, and some team-produced Union 76 portraits. When he returned to the Dodgers to finish his career from 1969 to 1972, Topps finally put him on its cards, in special sets, even as he was the manager of the Seattle Mariners, etc.

In 1975, Topps celebrated its 25th anniversary by issuing a subset looking back at all the league MVPs — and had to honor Wills for winning the NL award in 1962. But it did so by creating a retro looking card that appeared to be from that 1962 set. That card never existed in the 598-card set issued.

Rogie Vachon, Los Angeles Kings goalie (1971-72 to 1977-78):

In 1985, when the Kings picked his No. 30 ase the first to be retired in their 18-year existence, fans at the Forum were given megaphones to cheer Vachon, then the team’s general manager. Team owner Jack Kent Cooke had No. 30 put up on the wall at the Forum (which he owned) next to those three that he had retired for his Lakers – Jerry West, Wilt Chamberlain and Elgin Baylor. Between the time Vachon had left the Kings in 1978 and his ’85 retirement, the team had already given No. 30 to four others goalies — Ron Grahame, Doug Keans, Mike Blake and Markus Mattsson.

In 2016, almost 35 years after his final game, Vachon was also deemed worthy of Hockey Hall of Fame enshrinement. He had set Kings records for wins (171), shutouts (32) and games played (389), since passed by Jonathan Quick. It was pointed out that the time Vachon’s wait was believed to be the longest in the history of the Hall. Dick Duff, elected in 1996, had retired in 1972 after his 18-year career that included time in Montreal as Vachon’s teammate as well as 39 games with the Kings in 1969-70 and ’70-‘71 wearing No. 7.

It took a four-for-one trade in November of ’71 – four being the number of Kings shipped to Montreal, and Vachon as the one coming to L.A. – for Southern California hockey fans to see what the future of the team could look like with a legit long-term goalkeeper. Even if this was a player who, in his last game with Montreal, gave up four goals in 20 minutes. “I was very lucky to play for the Montreal Canadiens at the start of my career,” Vachon, a native of Palmarolle, Quebec, said. “My first shot on net was a breakaway by Gordie Howe. I stopped it and it kept me in the league for 16 more years.” The Kings’ 1967-68 expansion-season began with the traditional goalkeeper No. 30 worn by Terry Sawchuck, then 38 and an eventual Hockey Hall of Famer who had Stanley Cups in Detroit and Toronto. Vachon was part of a Stanley Cup team that shared the Vezina Trophy in ’67-68 with Canadiens teammate Gump Worsley. Vachon arrived in ’71-72 to share time with Gary Edwards. There was also a 21-year-old Billy Smith in the mix, but he was soon snatched away by the New York Islanders and became a legendary Stanley Cup winner and Hall of Fame goalie. By age 28, Vachon was the main man, and the Kings’ second place finish in the Norris Division in ’74-75 was his break out season – a 27-14-13 record, a league-best .927 save percentage, second-team All NHL and runner up to Bobby Clarke (and ahead of Bobby Orr) for the Hart Trophy as the league MVP. In ’76-’77, Vachon was third in the Hart voting behind Guy Lafleur and Clarke. Vachon’s seven-season run with the Kings produced a 171-148-66 record and a 2.86 goals against average. He remains the leader in the category Goals Saved Above Average. Vachon’s value to the Kings also came as an interim coach and as the general manager when the team acquired Wayne Gretzky from Edmonton in 1988.

Dave Roberts, Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder (2002 to 2004), Los Angeles Dodgers manager (2016 to present):

Robert’s appreciation of Wills led to him asking for and receiving No. 30, which had eventually been given out to players such as Derrel Thomas, John Tudor, Jose Offerman, Wilton Guerrero, Craig Counsell, Brad Penny, Casey Blake and, last, to Scott Schebler prior to Roberts taking possession. As a player, Roberts . Wearing is a manager, he has amassed in nine seasons the highest winning percent of any skippers in franchise history with at least 300 victories. That includes five 100-win season, two NL pennants and a World Series, and his 753 wins is third behind Hall of Famers Walter Alston (2,040) and Tommy Lasorda (1,599). At UCLA, Roberts was enshrined into the school’s Athletics Hall of Fame wearing No. 10.

Pam McGee, USC women’s basketball center (1980-81 to 1983-84), WNBA Los Angeles Sparks center (1998):

Playing with twin sister Paula (wearing No. 11), she was a two-time NCAA champion and had her number retired. As the WNBA launched in 1997, she played a season with Sacramento and was traded to Los Angeles to team up with Lisa Leslie, averaging 6.8 points and 4.8 rebounds at age 35. Her son, JaVale, ended up playing for the Lakers for two seasons (2018-19 to 2019-20, wearing No. 7).

Nneka Ogwumike, Los Angeles Sparks forward (2012 to 2023):

The WNBA’s No. 1 overall pick in 2012 out of Stanford, the league’s Rookie of the Year and, in 2016, the WNBA MVP after her game-winning shot. The eight-time All Star and 15th in the league career scoring ranks first in the franchise history in steals and field goal percentage, as well as win shares. As the president of the players association, she also led negotiations for the 2020 collective bargaining agreement that included increased salaries and travel benefits.

Lawrence McCutcheon, Los Angeles Rams running back (1973 to 1979):

A five-time Pro Bowl selection with four 1,000-yard rushing seasons who wore No. 31 as a rookie in L.A. in ’72, McCutcheon completed the Rams’ only touchdown pass in the 1980 Super Bowl XIV loss to Pittsburgh in Pasadena — a 24-yard halfback toss over the outstretched arms of Pittsburgh’s Jack Lambert, connecting with Ron Smith to give the Rams a 19-17 lead in the third quarter. His 158.3 QB rating for the Rams was far better than Vince Ferragamo’s 70.8 (0 TDs,1 INT). McCutcheon accounted for more than 6,500 yards, 26 rushing touchdowns and 13 receiving scores in his time. In the 1975 playoffs, McCutchen set an NFL rushing record with 202 yards on 37 carries in a win over the St. Louis Cardinals, breaking the mark of 31 carries for 196 yards set by Steve Van Buren of Philadelphia against the Rams in 1949. “Wearily stripping off his tape and baring his bruises, McCutcheon recalled that he once ran the ball 39 times for Colorado State against Brigham Young and gained 207 yards, but the feeling afterward wasn’t quite as grand as this,” it was reported in Sports Illustrated. ” ‘I like running out of the I formation, it’s what I did in college. I wasn’t all that tired. I could have carried at least four more times’.”

Todd Gurley, Los Angeles Rams running back (2016 to 2019): When the Rams moved back to L.A. from St. Louis, the running back from Georgia and reigning NFL Rookie of the Year became the most recognizable personality with his flowing dreadlocks and Carl’s Jr. commercials. In ’17, he was the AP Offensive Player of the Year and NFL MVP runner-up to Tom Brady after putting up a league-high 2,093 yards from scrimmage and 19 touchdowns. His ’18 Pro Bowl season was highlighted by 21 all-purpose touchdowns, again a league best. But in Super Bowl LIII in Atlanta, Gurley … disappeared? Ten carries, 35 yards. One catch for minus-1 yard. It was reported he had arthritis in his left knee. He stayed one more season in L.A. and finished in Atlanta.

Tracy Murray, Glendora High (1985 to 1989), UCLA basketball forward (1989 to 1992), Los Angeles Lakers (2002-03): He set the California state high school record scoring 3,053 points despite missing his freshman season due to injury That included a 44.3 points per game average and scoring 64 in the CIF State Division II title game. At UCLA, he had scoring average of 18.3 after three seasons and his 1,792 points were in the school’s Top 10 list. His Pac-12-leading 50.5 percent shooting from 3-point range as a senior ranks third in school history. He was a 2021 induction into the UCLA Athletics Hall of Fame. Very few get to wear the same number in high school, college and the pros. Murray did.

Have you heard this story:

Johnny Baker, USC football guard/place kicker (1929 to 1931):

The two-time All-American guard and part of the vaunted “Thundering Herd” was most famous for connecting on a 33-yard field goal with one minute remaining to lead the Trojans all the way back from a 14-0 deficit with 16 unanswered points in the fourth quarter and win, 16-14 – the Trojans’ first ever triumph in South Bend for a series that Knute Rockne and Howard Jones created in 1928. It led to a ticker-tape parade at the train station with some 300,000-plus in downtown L.A. in 1931. USC won the Rose Bowl and won the national championship with a 10-1 mark. Baker was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1983 and the USC Athletic Hall of Fame in its third class in 1997.

Ryne Duren, Los Angeles Angels pitcher (1961 to ’62): As a 32-year-old picked up in the expansion draft, Duran was the Angels’ first MLB All-Star representative, despite a 6-12 record and 5.18 ERA — one shutout, and two saves. Yet, the New York Yankees, who led him go after the 1960 season, borrowed him back for four games at the end of the ’61 season.

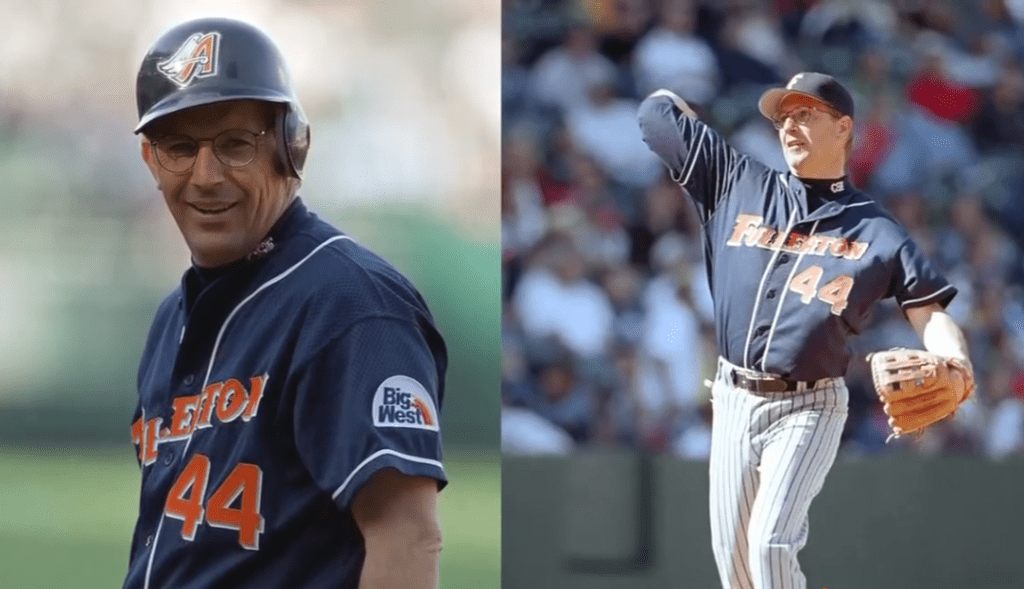

Greg Bunch, Cal State Fullerton basketball guard (1974-75 to 1977-78): A four-year starter who was part of the Titans’ only conference championship in 1975-76 and run to the NCAA Elite Eight with a 23-9 record. The team finished 9-5 in the PCAA, tied for third place, yet won the conference tournament and two games in the NCAA Tournament. Bunch led the Titans in scoring and rebounding all four seasons, averaging 14.5 points per game. His jersey No. 30 was retired.

Tim Hovland, Westchester High basketball (1974 to 1977): The El Segundo native was a three-sport star in high school before concentrating on volleyball at USC — a three-time All American who won the 1980 NCAA title. But his career on the beach volleyball circuit took him to new heights starting in 1979 and lasting more than 20 years. In 2009 he was inducted into the USC Athletic Hall of Fame. In 2020, he was inducted into the U.S. Volleyball Hall of Fame. In 2024, he was inducted into the International Volleyball Hall of Fame.

Mark Hendrickson, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2006 to 2007): Six times between 1992 and 1997, Hendrickson was drafted by MLB teams, but as a 6-foot-9 left-handed shooting power forward, he first wanted to see how he’d fare as a second-round choice in the 1996 NBA Draft draft by Philadelphia out of Washington State. After five seasons and 114 games in the NBA wearing Nos. 14 and 42 from 1996 to 2000, he picked up a baseball and had another 10-year run in the MLB, starting with Toronto in 2002 as a 28 year old. He posted a 6-15 record for the Dodgers and 5.01 ERA over 57 games (27 starts).

We also have:

Myles Jack, UCLA football linebacker/running back (2013 to 2015)

Curtis Rowe, UCLA basketball forward (1968-69 to 1970-1971)

Julius Randall, Los Angeles Lakers forward/center (2014-15 to 2017-18)

George Lynch, Los Angeles Lakers forward (1994-95): Also wore No. 24 as a rookie and No. 34 his third season.

Alexi Lalas, Los Angeles Galaxy defender (2001 to 2003)

Dokie Williams, UCLA football receiver (1978 to 1981)

Bruce Gossett, Los Angeles Rams kicker (1964 to 1969)

Bob Cerv, Los Angeles Angels outfielder (1961)

Ryan Miller, Anaheim Ducks goalie (2017-19 to 2020-21)

Ilya Bryzgalov, Mighty Ducks of Anaheim/Anaheim Ducks (2001-02 to 2007-08). Also wore No. 80 in 2014-15.

Who else wore No. 44 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

Jerry West, Los Angeles Lakers guard (1960-61 to 1973-74):

In the 2024 book, “The Basketball 100: The Story of the Greatest Players in NBA History” by the staff of The Athletic, Jerry West is slotted at No. 16, emphasizing his 12-time All-NBA selections, a 14-time All Star (every single season of his career), the MVP of the 1960 NBA Finals even though the Lakers lost to the Boston Celtics, and his three separate inductions into the Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield, Mass. — as an player in 1980, as a member of the 1960 Olympic gold medal team in 2010, and as a contributor for his years as a front-office executive building rosters in 2024. The bio by Sam Amick also recited the words from the plaque that is next to a statue of West outside the Lakers’ home arena:

“After nearly five decades as a player, coach and team executive, Jerry West is one of the true icons and legends that the game of basketball has ever known. His fearless style of play and emotional ‘wear his heart on his sleeve’ demeanor, made him a beloved figure to Lakers fans. One of the game’s all-time great players, Jerry was known during his playing days in the 1960s and early ’70s as Mr. Clutch for his propensity for hitting huge game-winning shots and his grace under pressure.”

It with some sad irony that when West died in June of 2024 at age 86, it was the Los Angeles Clippers who announced it through West’s family and not the Lakers. West had been working for the Lakers’ rival as a consultant at that point. He already disassociated himself from the Lakers, and the Magic Johnson draft choice, and the Kobe Bryant-Shaquille O’Neal championship roster he created as a general manager, after team owner Jeanne Buss had become a romantic partner with head coach Phil Jackson, noting the conflict of interest that was inherent with that relationship.

A 2023 feature story on him for The Sports Business Journal pointed out what while West has the NBA’s seventh-highest regular-season career scoring average at 27 points per game and the fifth-best playoff scoring average at 29.1 points a game, he often lamented about his his failures — the Lakers and he made the NBA Finals nine times, losing to Boston six times and New York twice before winning in 1972. “It’s almost like Peggy Lee’s song — ‘Is that all there is?’” said West. “That pretty much would apply to the way I felt about my career. … It’s hard for other people to understand how angry, and how sad, it all was. I have people, even today, say, ‘Look what it did for you.’ It didn’t do anything for me. I suppose there are lessons I learned from being second. But I don’t know what they are.”

That is reflected in his 2011 autobiograhy, “West By West: My Charmed, Tormented Life,” about his unhappy childhood in West Virginia and an often unfulfilling, anxiety-riddled career. Perhaps the more balanced account of his life comes from Roland Lazenby’s “Jerry West: The Life and Legend of a Basketball Icon” which came out a year earlier. The author’s research through interviews with his teammates, colleagues, and family members better describes how West channeled the frustration of his darkest moments into a driving force that propelled him, especially as an executive and talent evaluator.

Counting two championships won while West was a scout, the Lakers claimed six titles and made the finals 10 times in his 20 seasons with the organization. He was a two-time NBA Executive of the Year, including a season in Memphis.

He also had a 46.3 points per game average in a 1965 Western Conference series against Baltimore, which remains an NBA playoff record. He also hit one of the most famous shots in league history when he buried a 60-footer in Game 3 of the 1970 Finals against the Knicks. As the Lakers were down two at the time, and there was no 3-point shot rule, it forced a tie and pushed the game into overtime. Where the Lakers lost.

West will forever be nicknamed “The Logo” as the NBA’s trademark illustration was based on an image of him dribbling the basketball. He wasn’t fond of that. But it was fitting. The design in 1970 came inspired from a photo of West that appeared in Sport Magazine.

His No. 44 was retired by the Lakers in 1983. The only player in Lakers’ franchise history to wear it before him was a 6-foot-11 center named Chuck Share, for the very end of the 1960 season, during the Lakers’ last time spent in Minneapolis.

No. 44 will forever be West, never shared by anyone else.

Reggie Jackson, California Angels right fielder/DH (1982 to 1986):

In the five seasons Mr. October vacationed in Southern California at the behest of owner Gene Autry, Jackson only played a handful of post-season contests in October — nothing much during a five-game loss to Milwaukee in the ’82 ALCS (2-for-18, 2 RBIs, 1 HR) and playing in six games against Boston during the ’86 ALCS (5-for-26, 2 RBIs, 0 HRs). He was still given almost twice as much money as he was making in New York and also a hefty raise if the team passed various attendance thresholds. He was also given No. 44 off the back of manager Gene Mauch to make his arrival more pleasant. As an Angel, Jackson made the AL All Star team his first three seasons, tying for the league lead with 39 homers in 1982 (with 101 RBIs) in his first visit (as well as a league-high 156 strikeouts). Between the ages of 36 and 40, he attracted people, playing 687 games with the Angels (and striking out 690 times) with a .239 batting average. He hit his 500th career homer in Anaheim. He may have started as No. 9 in Oakland (and No. 31 in his rookie year in Kansas City), but he was No. 44 in New York and brought that as his identity to Anaheim and then, in one final Oakland season. His most well-known appearance in an Angels uniform may have been after his MLB retirement, playing himself in the movie “The Naked Gun: From the Files of Police Squad!” in 1988 where he is seemingly hypnotized and got to point a gun at an actress playing Queen Elizabeth watching a game at Dodger Stadium.

Gaston Green, UCLA football running back (1984 to 1987), Los Angeles Rams running back (1988 to 1990), Los Angeles Raiders running back (1993):