This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 55:

= Orel Hershiser, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Junior Seau, USC football

= Willie McGinnest, USC football

= Chris Clayborne, USC football

= Kiki Vandeweghe, UCLA basketball

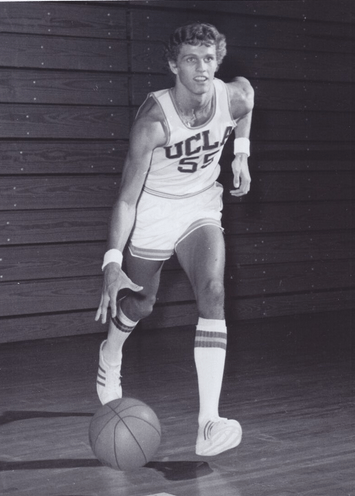

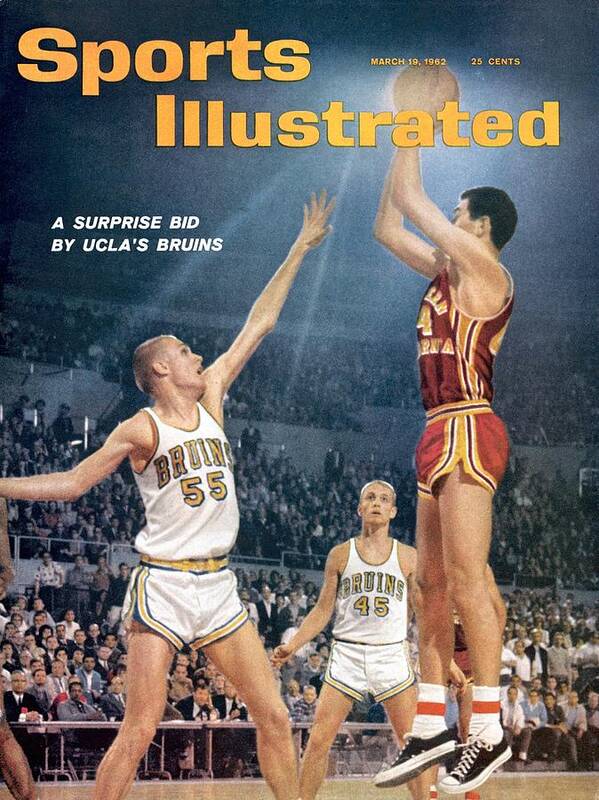

= Gary Cunningham, UCLA basketball

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 55:

= Jack Robinson, Pasadena City College football

= Tom Fears, Los Angeles Rams

= Maxie Baughan, Los Angeles Rams

The most interesting story for No. 55:

Gavin Smith, UCLA basketball forward (1973-74 to 1975-76)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Van Nuys, Sherman Oaks, Westwood, Hollywood, Calabasas, West Hills, Porter Ranch, Palmdale

Season 2, Episode 4 of “Homicide: Los Angeles,” the Dick Wolf-created Netflix documentary, is called “A Hollywood Affair.” It aired in July of 2024.

The synopsis: “When a Hollywood studio executive goes missing, a tumultuous affair comes to light, leading investigators to suspect foul play.”

Maybe this evolved from:

Season 25, Episode 47 of NBC’s “Dateline NBC” is titled “Dark Valley.” It aired in September of 2017.

The synopsis: “A philandering film executive, Gavin Smith, goes missing. Is he seeking a new life or has he upset a dangerous rival?”

Surely, host Keith Morison can make this seem even more supernatural.

What else ya got, gumshoe?

Season 5, Episode 9 of “The Perfect Murder,” another made-for-TV series that recreates crime scenes with actors. The title is “Jump Shot.” It aired in September of 2018.

The synopsis: “Hollywood ‘golden boy’ Gavin Smith — a 20th Century Fox executive and former star UCLA basketball player — disappears one night in May, 2012. His family and detectives search tirelessly for answers, but a group of heartless and selfish characters will hold fast to their secrets.“

Now the plot thickens. Maybe even into a pasty batter.

Yet, what’s truth and what’s fiction?

In the pantheon of UCLA’s storied basketball, was Gavin Smith really a “star” player with the Bruins’ program? Only if it helps draws in viewers. And how you define player at various points in his evolution.

Gavin Smith was 57 when he died. Or, rather, when he was murdered. And buried. And found two years later.

Let’s investigate all this further.

The background

Van Nuys News columnist Bernie Milligan wrote in 1973 about this 6-foot-6, 190-pound hot shot at Van Nuys High was, “according to most who see him play, the greatest thing to come along in basketball since Elgin Baylor.”

Gavin Smith, who by then was included in a Washington Post story that identified him as of the top 15 basketball players in the country, grew up in Sherman Oaks without playing organized basketball until he was 13. So when he sprouted up in height and average 27 points and 16 rebounds a game in his senior year at Van Nuys to win Mid-Valley League MVP, wearing No. 33, the days that he was remembered as a baseball pitching prospect for the school that created Don Drysdale was long gone.

As Smith told Milligan: “I was a scatter arm and never knew exactly where the ball was going.”

To further prove his athleticism, Smith won the league championship in the long jump and finished sixth in the L.A. City final.

When the Los Angeles Times posted a March 20, 1973 story announcing the L.A. All-City basketball team — Crenshaw’s Marques Johnson was named Player of the Year — it noted that Smith had been “called by one college coach the ‘best white player in the country’.” That quote came from Washington State head coach George Raveling, who had been actively recruiting him. Raveling could get away with saying such a thing that these days might raise eyebrows.

A month later, after returning from the Dapper Dan Classic high school all-star game in Pittsburgh, Smith, who had been a second-team Parade Magazine All-American, gave Raveling his answer — he decided to bank on John Wooden and UCLA.

Wooden’s assistant, Frank Arnold, got him to join a recruiting class that included the same Marques Johnson, plus Richard Washington and Jim Spillane. UCLA fans were told that Smith would remind them of former Bruins star Keith Erickson, both in looks and how he played.

UCLA, coming off seven straight NCAA titles, had a 1973-74 roster with seniors Bill Walton, Keith Wilkes and Tommy Curtis, plus juniors David Meyers and Pete Trgovich. Smith could likely have been a starter anywhere else with freshmen eligible now.

“The main reason I chose UCLA was that if I play there, I’ll be playing against the best players and that’s why they win championships,” said Smith. “The players are so good that if you don’t do the job they can have someone else who can.”

As a freshman, Smith practiced with the varsity team and got into seven games, scoring nine points with five rebounds. In nine of the Bruins’ 18 JV games, he averaged 15.7 points, third best on the team, and seven rebounds a contest.

As a sophomore, Wooden had Smith come off the bench in 17 games. As he scored 60 points with 18 rebounds, a key contribution was in an 82-75 win at Pauley Pavilion in December of ’74 against rival Notre Dame. Smith his two long jump shots over the Irish’s 2-1-2 zone during a 10-point run that got UCLA back in the game.

“I was extremely pleased with Gavin,” said Wooden afterward. “Gavin played under control, dribbled well and made a few good shots.”

The Bruins won the 1975 NCAA title that season, the last for Wooden as he retired. Smith didn’t play in that 92-85 championship win over Kentucky.

Now Smith went into his junior year finally declaring a major — political science — and trying to declare a reason new head coach Gene Bartow should give him more playing time.

Smith still couldn’t break into the starting lineup, stuck now between a shooting guard and a small forward depending on the opponent. He played in 30 games for a Bruins’ team that won the Pac-8 at 12-2, and finished fifth in the final AP poll at 27-5. Smith scored 179 points (6.0 a game) to go with 55 rebounds (1.8 a game) and 22 assists (0.7 a game). During a stretch of games in January and February of ’76, there were some double-digit point production. The Pauley Pavilion crowd picked up on it and often chanted “Shoot, Gavin, shoot!”

UCLA’s season ended with a bitter loss in the NCAA national semifinals to Indiana, 65-51. Smith managed six points in nine minutes with three personal fouls in that game, but in a follow up in the Los Angeles Times, he wasn’t shy about complaining about his limited playing time, benched after his fast-break layup cut Indiana’s lead to six points with six minutes left.

“I could understand it if I were throwing up bricks,” said Smith. “But I wasn’t. I don’t understand why I’m not in there when others are cold.” He also pointed out teammates were playing with a lack of intensity. “We should have had the attitude that we’re the defending champs and Indiana had to beat us. I didn’t have much to do with anything but when I’m in a game I’m fired up and I’ll even scream at some of our dudes.”

In those days, there was a third-place game, and UCLA handily defeated Rutgers, 106-92. Smith had eight points (3 of 9 shooting) and six rebounds in 15 minutes off the bench.

It would be his last game for the Bruins.

On that ’75-’76 roster, nine UCLA players would go into the NBA. Marques Johnson, of course, as eventual winner of the Wooden Award, was coming back for his senior year. David Greenwood now starting on the front line with Richard Washington. Bartow had Palisades High’s Kiki VanDeWeghe and Redondo High’s Gig Sims as new big men on their way in for the ’76-’77 season. Guard play would be split between senior Jim Spillane, junior Raymond Towsend and sophomores Brad Holland and Roy Hamilton.

Smith was caught in between. By July, 1976, his fate was sealed. UCLA declared him scholastically ineligible. The story wasn’t clear how that happened, but it did. and he was free to go.

When Smith’s transferred out to the University of Hawaii, one of his original three schools of interest coming out of high school, VanDeWeghe would get his Bruins’ No. 55 jersey.

Given not just a starting role but a starring one on the island, Smith averaged 23.4 points a game for the Rainbow Warriors, a program that had started just seven seasons earlier and was still an independent.

Just before Smith arrived, at the end of the ’75-’76 season, former graduate assistant Rick Pitino had his first head-coach experience on an interim basis, at age 24. But something was amiss. As Hawaii hired Larry Little as its new coach, he brought in Smith, and the program finished 9-18 in ’76-’77, just as it was hit an NCAA sanction related to Pitino recruiting violations and player benefits.

Smith set four Hawaii program records — most points in a single season (608), best scoring average (23.4), plus most field goals and most field goal attempts (252 of 571), all before the 3-point line came into effect. Those marks that still stand. He had a season-best 37 points with 13 rebounds in an 18-point loss to Oregon State. He also led Hawaii in rebounds (6.5 a game).

He was on the West team for the Aloha Classic college All-Star game, teammates again with Johnson and Spillane.

Not all was smooth sailing in Hawaii for Smith, known for wearing his hair long held with a bandana and bringing his dog to practice. He was suspended one game when he and some teammates broke a curfew. He was also on shaky ground when the school’s second semester started and he hadn’t registered for classes, was thought to be ineligible, but Little scrambled to get him enrolled again.

In a March, 1977 story for the Los Angeles Times, reporter Earl Gustkey caught up with Smith as Hawaii faced Long Beach State at the Long Beach Arena. In that February 24 game, Smith missed his first seven shots, including three air balls, was 2-for-12 at halftime as his team trailed by 21, and ended up with just 12 points in a 110-79 loss before fouling out as well as getting a technical foul. A few games later, in a 40-point loss at UNLV, Smith had 18 points but fouled out with 14 minutes left.

The Times’ feature on Smith ran in the Honolulu Star-Advertiser under the headline “Smith, the former future UCLA star.”

“Geez, I was horrendous,” said Smith, back to wearing the No. 33 from Van Nuys High, talking about that loss in Long Beach.

Smith then explained how his situation at UCLA ended:

“I had a long talk with coach Bartow and he told me it’d be very difficult to keep me out of the starting lineup this year, but it wasn’t a guarantee. I was fed up and a little perturbed. I mean, I’m no average ball player and I’d sat for three years.

“After three years, after all the mental and physical exertion from my body, I’d gotten zero in return in terms of playing time. I just became unhappy with the situation. So after my talk with Bartow, I just left.

“A lot of people think I flunked out of UCLA, but I didn’t. I just left. I didn’t even both to drop my classes. I’d met a lady from Santa Rosa, so I went up there with her.”

Women can do that to you.

The aftermath

A 2024 issue of People magazine did a whole big to-do about the life and times of Gavin Smith. It’s probably most appropriate we allow that magazine to pick up the story from here with its collated research:

After playing, it seemed almost natural that Smith pursue a career in the entertainment industry — his mother was an assistant movie producer, as well as a script supervisor and got him involved in the business at an early age.

The stereotypical California sun-tanned, tall and handsome figure first came in as a stuntman. He hurt his back. The meds he used caught up with him.

Smith’s IMDb.com resume also notes small acting roles in three film and TV spots — a bartender in “Cobb, a bodyguard in “Glitz,” and a role in “Swingin’ in the Painter’s Room” — an 11-minute black-and-white film where Smith is ID’d as “Guy with Fur Hat.”

As an aspiring actor, Smith was also the stereotypical part-time waiter scrambling for a paycheck. That’s where he first met his eventual wife, Lisa Dobson.

“I just thought he was charming and I was thrilled when he asked me for my number,” Dobson said on Dateline in 2017. “He was a wonderful husband. He was a gentleman … He made me feel like a princess.”

Smith found work in 20th Century Fox and somehow worked his way up to the head of film distribution. His top projects included the original “Star Wars” trilogy, “Titanic” and “Avatar,” as a liaison between the studio and theaters. He also got involved in the creative process, working from the studio’s Calabasas office.

Smith and Dobson had three sons: Evan, Austin and Dylan. While Smith worked in the film industry, Lisa raised the kids. Evan, born in 1990, would grow to a 6-foot-7 forward at Calabasas High, averaging 17.7 points and 9.3 rebounds as a senior, making the CIF-SS Division III first team. Wearing No. 22, he went to play at USC from 2009-10 to 2010-11, getting into just 11 games as a freshman and sophomore for coach Kevin O’Neill before an injury derailed him.

According to friends who spoke to The Daily Beast in 2012, the couple’s relationship had been on the rocks. Smith had substance abuse issues as well as financial problems as they bought a house during the 2008 financial crisis and were underwater with bills.

“They were not separated. They were just going through normal stuff couples go through,” Evan told E! News in 2012.

Dobson turned to religion for comfort. Smith turned to the company of Chandrika Cade, a married woman he met during a 2008 stay in rehab center. When Smith’s family found out about his affair, Smith insisted he would call things off — but his promise was only temporary.

“I was the love of Gavin’s life,” Dobson said. “He adored me. Our family was exactly what he wanted to have. He just got lost.”

Then, in May, 2012, Smith officially did get lost. He disappeared.

The L.A. Sheriff’s Department reported that Smith was last seen in the Agoura Hills/Oak Park area in a black Mercedes with the California license plate 6EKT004. The family asked publicly for anyone’s help in the search.

As it turned out, on the evening of his disappearance, Smith secretly met up again with Chandrika Cade. This time, her husband, convicted drug dealer John Creech, tracked them down.

Creech, who found out about the affair in 2010, killed Smith with his bare hands.

Smith’s body wasn’t discovered until more than two years later.

The trial and aftermath

Evan Smith told People Magazine in 2019: “(My dad) just messed up. He got a little lost, and I know if he was still here today that he would be so apologetic for how things finished up.”

As more and more information came out, it was revealed that Evan and one of his brothers had actually approached Creech to apologize for their father’s actions, begging for Creech not to retaliate. Creech told the boys that they saved their father’s life with that visit.

Evan then told his father that he had to “be better” if he wanted to continue to be a part of their family unit. Learning later his father had continued the affair, Evan says he was “crushed.”

In the days before his 2012 disappearance, Smith attended the CinemaCon movie convention in Las Vegas. He went back to the San Fernando Valley, but opted to stay with a nearby family friend in Oak Park on the night of May 1 instead of his West Hills home.

Smith and the friend watched television together before she retired to bed, expecting him to do the same later in the evening.

“They had already gone to bed,” Dobson told ABC. “So, he was still downstairs watching TV when our friend went to bed. And he was going to be coming up to bed shortly.”

But, at around 10 p.m., Smith left in his black Mercedes, wearing purple workout pants that belonged to Evan and he intended to wear to bed. He left most of his belongings behind. According to phone records acquired by police, Smith’s last GPS signal came from Sylmar at 4:30 a.m. on May 2, about 30 minutes from his home.

That morning, his family sensed something was wrong because Smith was supposed to pick up Austin for school. When that didn’t happen, and he didn’t make it to work, Dobson filed a missing person report. Flyers went out. A hotline was established. A $20,000 reward was offered. An episode of “America’s Most Wanted” even did a segment on the case.

At that point, the LAPD started to investigate Creech and Cade, going to their Canoga Park home, seizing cell phones and computers as well as their SUV.

In February of 2013, L.A. County Sheriff’s deputies found Smith’s Mercedes in a Simi Valley storage facility, led to that unit after Creech’s vehicle was found during a drug bust. After inspection, the evidence led to the belief that was where Smith was murdered. Creech was now the person of interest, as he was already serving two years of an eight-year sentence in L.A. County Men’s Central Jail on drug charges.

On Oct. 26, 2014, Smith’s remains were discovered in a shallow grave by a group of hikers in Palmdale, going into Angeles National Forest, 70 miles away from the home where he disappeared.

In January 2015, the district attorney officially filed murder charges against Creech. A grand jury indicted him. In the months that followed, hundreds of pages of court transcripts were made public through the Los Angeles Times.

Testimony from Cade revealed she met up with Smith late in the night when he disappeared. Her husband tracked her location and snuck up on the pair. Cade said Creech immediately began beating Smith and threatened to harm her as well. After pleading for her husband to stop, she fled the scene and returned home in her own vehicle.

Creech then beat Smith to death. The county coroner said Smith’s skull had been crushed on both sides.

Creech decided to store Smith’s Mercedes in a friend’s garage in Porter Ranch, then went to the desert to bury Smith’s body. Creech and several accomplices kept Smith’s death a secret for years as the investigation was underway.

When the trial began in 2017, the Los Angeles Times headline read: “A lurid tale of sex, deceit and brutality as trial begins in the slaying of Fox executive.” Wonder where the subsequent TV shows got their titles from.

Prosecutors described Smith’s murder as “an act of almost stunning brutality — almost indescribable violence.” Creech’s attorney, Deputy Public Defender Irene Nuñez, called her client’s actions self-defense, that he feared for Cade’s safety, found the two in Smith’s car, and Smith began to attack him. He also alleged Smith chased him with a weapon — never found — causing Creech to fight back.

When Creech took the stand, he took “full accountability” for not contacting authorities to help find Smith, per NBC News.

Cade also testified that Creech was covered in blood when he came home later that morning of Smith’s disappearance. She said her husband told her Smith was dead, and they burned their clothes in the home’s fireplace.

At the end of the trial, the jury was presented with several options including first- and second-degree murder. Instead, they found Creech guilty of voluntary manslaughter after an hour of deliberation.

In July 2017, Creech was sentenced to the maximum 11 years in prison. His accomplices were not charged. Cade was not charged. They were given plea deals. In 2019, Creech’s conviction was upheld by a state appeals court.

Detective John O’Brien was disappointed in the verdict, suggesting that the jury had been biassed against Smith because of his infidelity.

“My opinion is that they didn’t like the fact that Gavin and Chandrika had an affair,” he said. “I think the jury felt that he went back even after he had been warned, so in a way he kind of got what was coming to him. I don’t even understand that logic, because there’s no right to kill somebody.”

Gavin Smith’s friends continued to remember him as a “larger-than-life” personality devoted to his sons and hoping to repair his relationship with his wife. Following his death, they worried his memory had been tainted by the sensational circumstances of the murder case.

“He wasn’t some adulterer having flings here and there… that just wasn’t him,” Smith’s brother Greg said. “Unfortunately this liaison cost him his life. Smiling, always happy, he was bigger than life. I loved him and I miss him, but he’ll always be here. Always.”

Makes you wonder: If Gavin Smith had been shown the script for this story, would he have believed it?

Instead, it gets retold now by those who can still milk it for all its details. Over and over again.

Who else wore No. 55 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

Orel Hershiser, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1983 to 1994, 2000):

Best known: The facts and figures of the 1988 season, confirming Orel Hershiser winning the Cy Young Award, World Series MVP, NLCS MVP, broke the MLB record for consecutive scoreless innings at 59 (which meant going 10 innings in a 1-0 win in his last start to do it of the regular season), a Gold Glove, finishing sixth in the MVP voting and doing whatever was necessary to pitch the Dodgers to the World Series title as a heavy underdog to both the New York Mets in the NLCS and the Oakland A’s in the finale secures a fate that he never have to buy a drink in Southern California for as long as he lives.

His decision to then become a broadcaster and mesh into the Dodgers’ SportsNet L.A. broadcast team has not only kept him visible, but some still congratulate him for his induction in the Baseball Hall of Fame for still having his “world record,” as he told us in 2013.

Some of his memorabilia may be on displayed in Cooperstown, but there is no plaque. He had just 11 percent of the votes in his first year of eligibility of 2006. Voters in the Veterans Committees in 2017 and ’19 didn’t generate enough interest. The Bill James’ “Hall of Fame Monitor” has him with a score of 91, when 100 is the passing threshold. Hershiser’s 56.0 career WAR, and 40.1 seven-year peak is comparable to Hall of Famers such as Catfish Hunter and Dazzy Vance during his career trajectory. Having led the National League in innings pitched for three straight seasons (1987 to 1989) with 33 complete games in that span and posting ERAs of 3.06, 2.26 and 2.31 were his peak. A 204-150 record and 3.48 ERA in an 18-year career over more than 3,000 innings included a comeback from revolutionary shoulder surgery by Dr. Frank Jobe. That led to Hershiser’s No. 55 put into the Dodgers’ “Legends” status in 2023, and eventually having it somewhat retired in the “Ring of Honor.”

Not well remembered: The Dodgers’ 17th round pick in 1979 out of Bowling Green left as a free agent to play with Cleveland, San Francisco and the Mets, but he returned to the Dodgers in 2000 at age 41. He lasted until June 27, showing up for 24 innings, amassing a 1-5 mark and 13.14 ERA in six starts.

Kiki VanDeWeghe, UCLA basketball forward (1976-77 to 1979-80); Los Angeles Clippers forward (1992-93):

Best remembered: Out of Palisades High, the 6-foot-8, 220 pounder got his basketball DNA from his father, Ernie “Doc” Vandeweghe, a shooting guard for six seasons with the NBA’s New York Knicks (1949 to 1956) before starting a well-known medical practice in Southern California. Four years as a Bruin produced a UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame induction in 1994. The All-American and NCAA post-graduate scholarship award winner lead the Bruins to a national championship appearance his senior year (losing to Louisville) and losing in the West Regional final in his senior year (with an AP No. 2 ranking). He averaged 14.2 points (11th in the Pac-10) and 19.5 points a game (second in the conference) his final two seasons at UCLA, plus 6.3 and 6.8 rebounds. That led to a first-round draft choice of Dallas in 1980, but a holdout led to a trade to Denver.

Not well remembered: The last of his 13-season NBA career came with the Clippers, starting three of his 41 games for a 41-41 team under coach Larry Brown. In 2013, Kiki Vanderweghe change the spelling of his last name to VanDeWeghe, to honor as it was spelled in its original Belgium by his departed grandfather and namesake as Ernest M. VanDeWeghe III.

Gary Cunningham, UCLA basketball (1959-60 to 1961-62):

Best known: The 6-foot-6 sharpshooter at Inglewood High became a three-year starter was on the Bruins’ first Final Four appearance team in the ’62 tournament. His value to the program came as John Wooden’s assisant coach from 1965 to ’75 on six national title teams, including a run as the freshman team coach that featured all the top incoming players such as Lew Alcindor. He then became UCLA’s head coach from 1977 to ’79, compiling a 50-8 record with a No. 2 ranking in the final polls both seasons. He has the greatest winning percentage as a UCLA coach at .862. He retired in 2008 after 13 years as the athletic director at UC Santa Barbara.

Not well remembered: His 2001 UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame induction notes that Cunningham was not only the ’62 team’s co-captain, he was also winner of the Ducky Drake Award for best spirit, inspiration and team contribution and a three-time winner of the Ace Calkins Award as Bruin free-throw champion.

The USC “Club 55” tradition:

Junior Seau, USC football linebacker (1987 to 1989):

Best known: Tiaina Baul “Junior” Seau Jr., seems to have started a tradition of having the No. 55 bestowed upon the Trojans’ most influential linebacker. Because of academic restrictions, Seau played only two seasons for the Trojans. In 1989, he had 19 sacks and 27 tackles for loss and was named a unanimous All-American and the Pac-10 defensive player of the year. His two years produced 107 tackles and 33 tackles for a loss. Seau died on May, 2012 of a self-inflicted gun wound to his chest. He was 43. Studies by the National Institute of Health showed Seau had chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) brain disease cause by repetitive head trauma.

Not well known: In ESPN’s 2020 list of the 150 greatest college football players in the game’s first 150 years, Seau ranked No. 105. His bio noted that while at USC: The Trojans went 19-4-1, won back-to-back conference titles and played in two Rose Bowls in his two seasons. After bypassing his senior season, Seau was the fifth pick of the 1990 NFL draft and played 20 seasons as a pro, and 12-time Pro Bowl player and a member of the NFL’s 100th Anniversary Team. He wore No. 55 throughout his professional career and had it retired by San Diego, which took him No. 5 overall in the 1990 draft. In 2015, he became the first player of Polynesian and Samoan descent to be inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Willie McGinest, USC football linebacker (1990 to 1993):

Best known: McGinest was All-Pac-10 Conference three straight years and had All-American status. During his senior year, he was a Lombardi Award finalist. Starting every game at weak-side defensive end, McGinest finished at USC with 193 tackles (134 solos), 29 sacks (171 yards), 48 tackles for loss (238 yards), and 26 passes batted away. The fourth overall pick of the 1994 draft by the New England Patriots, McGinest had a 15-year NFL career with two Pro Bowls and three Super Bowl titles.

Not well remembered: Out of Long Beach Poly High, McGinest had all-state honors in football and basketball.

Chris Claiborne, USC football linebacker (1996 to 1998):

Best known: The only USC player to ever win the Butkus Award for the nation’s top linebacker in 1998 was given No. 55 by Trojans head coach John Robinson after he committed from Riverside North High, where he also wore that number. “We told him he had to wear 55 because he was going to be great player,” Robinson said. “He didn’t think it was great at the time. Once he got in it and recognized it was special, he liked it.” The Pac-10 Defensive Player of the Year in ’98 led USC in tackles with 107 (77 solo), interceptions (six, returning two for touchdowns) and in pass deflections (16).

Not well remembered: The No. 9 overall pick in the 1999 draft by Detroit went on to become the head football coach at Calabasas High in 2018 and was on the USC staff in 2020 as a quality control analyst.

Keith Rivers, USC football linebacker (2004 to 2007):

Best known: Born in Riverside, Rivers decided to go to USC over many other offers to be the latest No. 55. He started out on USC’s ’04 national title team as a freshman and had 215 tackles in his 49-game career, leading to the No. 9 overall pick of Cincinnati in the 2008 NFL draft. Rivers once said of honoring Seau by wearing No. 55: “It started with him and lived through all of the 55s that carry the torch.”

Not well remembered: USC linebacker coach Ken Norton Jr., gave Rivers the nickname “The Shark” for his aggressive play.

Have you heard this story:

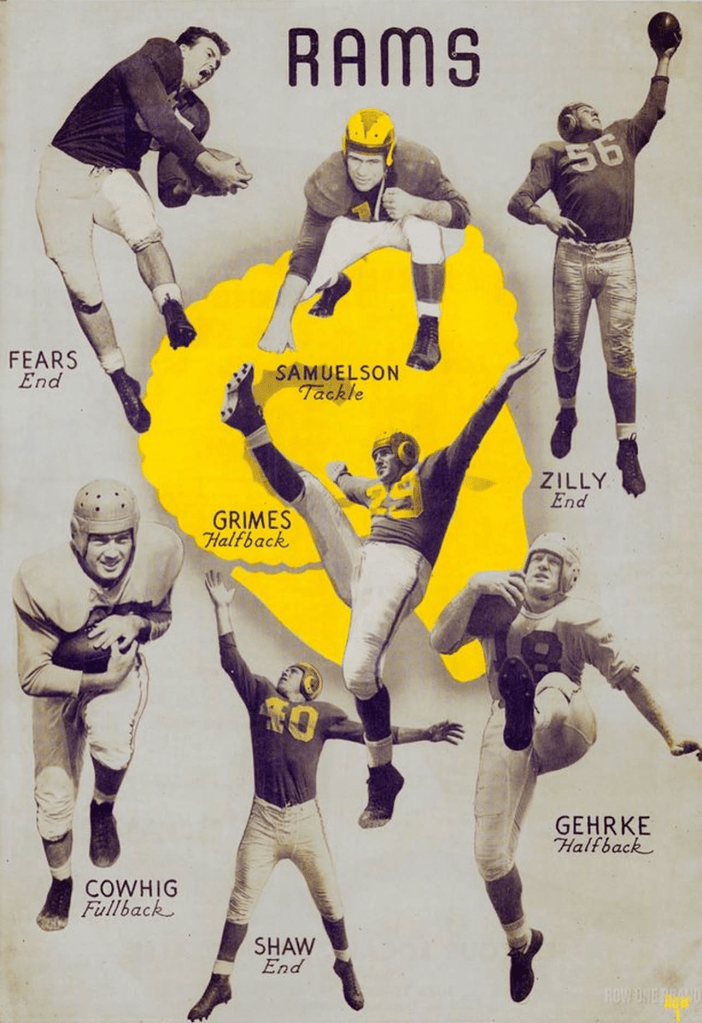

Jack Robinson, Pasadena Junior College football running back (1938):

A statue sits outside the Rose Bowl depicting Robinson’s days at the junior college and sporting the No. 55. It commemorates the 13 games he played at the Rose Bowl — four when he attended John Muir High School and nine during his time attending Pasadena Junior College (today known as Pasadena City College). In one notable game against Caltech, Robinson scored a Rose Bowl-record touchdown with a 104-yard kickoff return. That record, which still stands, is likely the inspiration for the statue’s stance.

Tom Fears, UCLA end (1946 to ’47); Los Angeles Rams right and left end/defensive end (1948 to 1956):

Best known: The first Mexican-American voted into the Pro Football Hall of Famer and ever drafted by an NFL team in 1945 came from Guadalajara to an Hispanic mother and American father. Fears was a standout at L.A.’s Manual Arts High and joined his friend, Toby Freedman, from Beverly Hills High, to enroll at Santa Clara University. Drafted for military service for World War II, he had three years of service and played football at the Colorado Springs platoon. An 11th-round draft pick of the Cleveland Rams in ’45, Fears went to UCLA instead, wearing No. 50 for two seasons as an All-American for the Bruins. But when the Rams’ franchise moved to Los Angeles in ’47, Fears joined them in ’48 for a $6,000 contract and $500 bonus. He led the NFL with 51 receptions despite starting just one of the 12 games. He’d lead the NFL again with 77 catches (a league record) and nine touchdowns in ’49 (to go with 1,013 yards) and, in his only Pro Bowl season, was tops with 84 catches (breaking his own league record) with 1,116 yards and 93 yards a game. In 1952, Fears switched to No. 80 and would keep that the last five years of his career, lasting all nine years in L.A.

Fears died at age 76 in 2000 in Palm Desert as a member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, the College Football Hall of Fame, and included into the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 1989. Fears was also a Rams’ coach under former teammate Bob Waterfield in the 1950s and the first Latino head coach in the NFL when he took over the expansion New Orleans Saints in 1967.

Not well remembered: Fears was named president of the All-Sports Council of Southern California and spent a year coaching at San Bernardino JC and Chapman College. He was director of player personnel for the USFL’s Los Angeles Express in its first year.

Maxie Baughan, Los Angeles Rams linebacker (1966 to 1970):

Best known: A Pro Bowl pick in four seasons and first-team All-Pro three times during his five seasons with the Rams, Baughan pulled in 11 interceptions total with the franchise. He came to Los Angeles in a trade to play for head coach George Allen, starting his first season with the organization. Baughan was chosen to be the Rams’ defensive captain and was in charge of signal calling. After an injury-plagued 1970 season, in which he played in only 10 games, Baughan retired from the NFL. But his contractual rights were traded in 1971 to Washington — where Allen had just gone off to work. That deal included Baughan going with Jack Pardee, Myron Pottios, Diron Talbert, John Wilbur, Jeff Jordan and a 1971 fifth-round pick to the Redskins for Marlin McKeever, first- and third-round picks in 1971 (which turned out to be Isiah Robertson and Dave Elmendorf), plus five-more draft picks. After two years as a defensive coordinator at his alma mater, Georgia Tech, Baughan was coaxed by Allen to become a player-coach with his Redskins in 1974 at age 36 for one last season. He was up for Pro Football Hall of Fame considerations in 2025.

We also have:

Albert Pujols, Los Angeles Dodgers (2021)

Russell Martin, Los Angeles Dodgers (2006-2010, 2019)

Jason Isringhausen, Los Angeles Angels (2012)

Tim Lincecum, Los Angeles Angels (2016)

Hideki Matsui, Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim (2010)

Matt Millen, Los Angeles Raiders (1980 to 1988)

Carl Ekern, Los Angeles Rams (1976 to 1988)

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 55: Gavin Smith”