This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

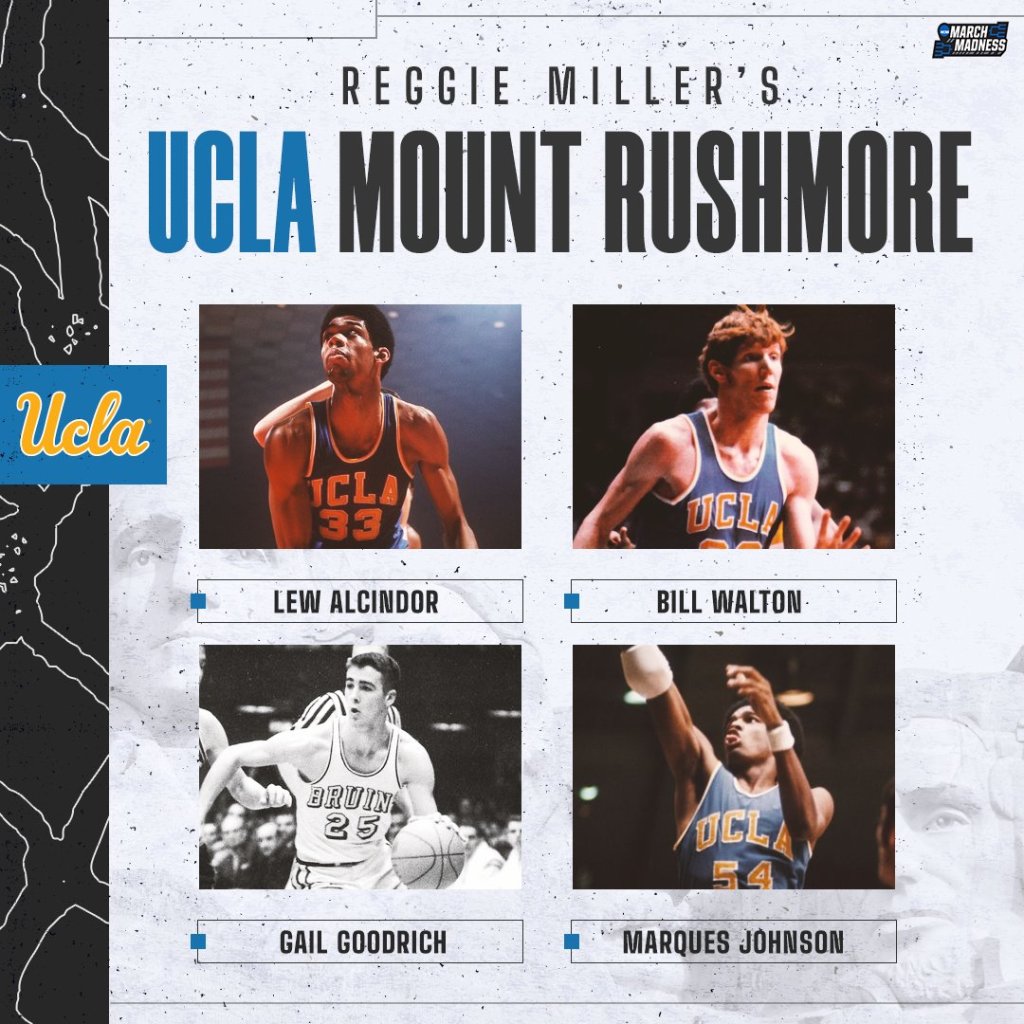

The most obvious choices for No. 54:

= Marques Johnson, UCLA basketball

= Larry Farmer, UCLA basketball

= Edgar Lacy, UCLA basketball

= Kenny Fields, UCLA basketball

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 54:

= Horace Grant, Los Angeles Lakers

= Tim Leary, Los Angeles Dodgers

The most interesting story for No. 54:

Marques Johnson, UCLA basketball forward (1973-74 to 1976-77)

Including Crenshaw High (1970 to 1973) and the Los Angeles Clippers (1984-85 to 1986-87)

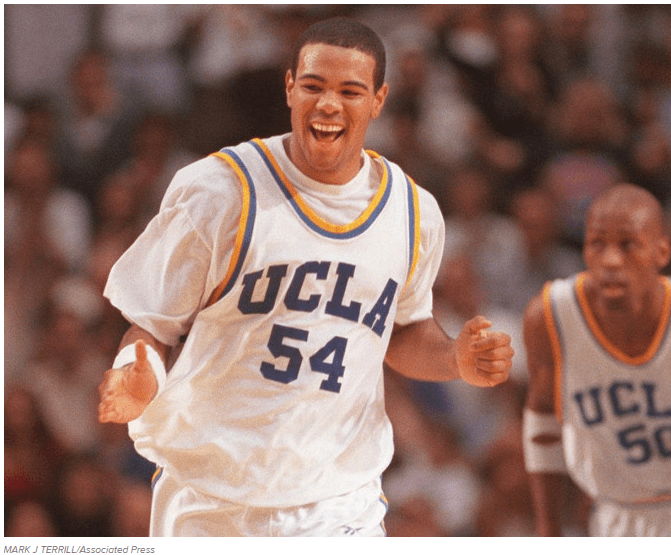

Kris Johnson, UCLA basketball forward (1994-95 to 1997-98)

Josiah Johnson, UCLA basketball forward (2001-02 to 2004-05)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Inglewood, Windsor Hills, Crenshaw, Westwood (Pauley Pavilion), Los Angeles (Sports Arena), Hollywood

The play was the thing at every big stage of Marques Johnson’s career.

On his Internet Movie Database profile, there is a confluence of links, notes and anecdotes about how he picked and rolled his way into TV and movies, assisted by the plays he made on the basketball court as a Los Angeles city legend, a Westwood warlock and a regal Clipper.

He did, after all, graduate from UCLA with a Theater Arts major degree.

Look up the 1992 “White Men Can’t Jump” in 1992, which came out just a couple years after Johnson’s 11-year NBA career was officially over. Who else could handle the role of a hoodlum hoopster named Raymond in the Ron Shelton movie?

Johnson deftly pulls out a switch blade on Wesley Snipes and Woody Harrelson. But when that doesn’t scare then enough, the script calls for him to run to his car and threaten to get a gun. Paranoia ensues.

Even if the casting crew couldn’t get his name spelled correctly — sometimes, the credits show him as “Marcus” — there were more cameos with TV shows like “Hangin’ With Mr. Cooper,” “The Sinbad Show,” “Baywatch” and “Castle.” If only “Space Jam” could have come earlier.

The movie site bio also has an interesting quote attributed to Johnson, one that has nothing to do with show business. It’s more relatable to how he was directed on the court by UCLA coach John Wooden, following the legendary Pyramid of Success philosophy.

Johnson said: “At the time it was like, Pyramid Shmyramid, Where’s the party at? Where are the girls at? I didn’t want to hear anything about principles and living a life of integrity at that time. But as you get older, and you have kids, and you try to pass on life lessons, now it becomes a great learning tool.”

That quote was added to the 2010 New York Times obituary on Wooden, who died that year at age 99.

In the same piece, Johnson added about Wooden: “He was almost a mystical figure by the time I got to UCLA. I couldn’t really sit down and have a conversation with him about real things just because I had so much reverence for him — for who he was and what he had accomplished. … He never gave that perception that was the way he wanted you to treat him, but it was just how it was.”

A deeper dive on Johnson’s IMDb.com bio has one executive producer credit, for a 2011 short film called “The Wooden Effect.” His sons Kris Johnson and Josiah Johnson are also listed as producers. Josiah directed it. It makes sense. That Wooden had that kind of halo effect that deeply affected the Johnson basketball lineage. It produced its own pyramid of family pride.

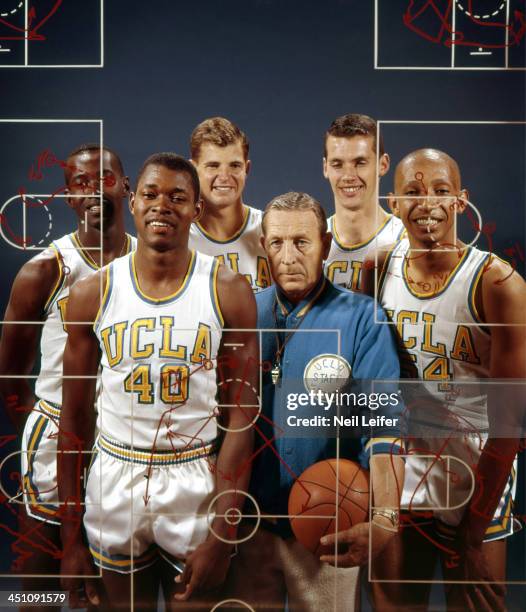

It started with Marques Johnson, the L.A. City Player of the Year out of Crenshaw High. He would be picked for California Interscholastic Federation’s 100th anniversary All-Century team. Johnson took on the responsibility of wearing No. 54 for the Bruins — shared by many standouts of the past.

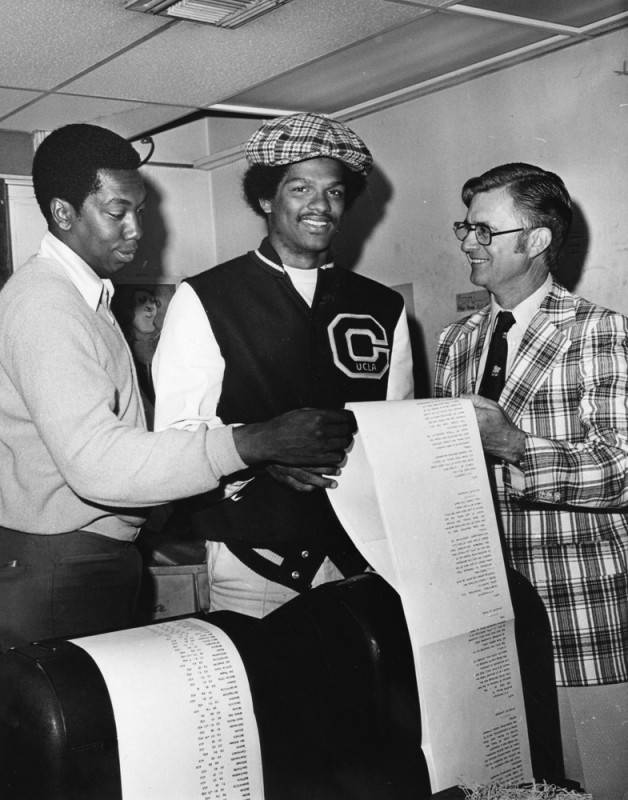

It was fortuitous timing that Johnson would be the last All-American player Wooden coached at UCLA before his 1975 retirement coinciding with the Bruins’ 10th NCAA title under his watch. Two seasons later, playing for coach Gene Bartow, Johnson was the first recipient of the John R. Wooden Award as the national college basketball player of the year, which has become the sport’s equivalent of the Heisman Trophy.

Flash forward 20 seasons later.

Kris Johnson, Marques’ oldest of five sons, enters UCLA’s basketball program as a freshman, and the program ends a long drought by winning the NCAA title, its first since Marques Johnson was a creator in that process. Kris Johnson wore No. 54 and was also an All-L.A. City Player of the Year at Crenshaw High, marking the first father-son duo to earn that honor as well as win a national college basketball title at the same school.

Josiah Johnson, Marques’ next-oldest son, would also play basketball at UCLA. He wore No. 54. He came to Westwood from Montclair Prep.

By 2018, Kris Johnson’s son, Will — Marques’ grandson — made the University of Oregon basketball roster, first as a walk on, then earning a scholarship, out of Palisades High. And wearing No. 54.

“Brought tears to my eyes,” Marques Johnson said of seeing Will Johnson during warmups before a Feb., ’18 Oregon-UCLA game at Pauley Pavilion, a place where No. 54 hangs from the rafters. “It was the realization of a dream that started when he was 7, 8, 9 years old.”

And a dream the whole family could share.

The background

Born in Natchitoces, Louisiana, Marques Johnson was destined to play at UCLA, according to his father, Jeff, a high school coach in that region of the country. The kid was named after the famous Harlem Globetrotter, Marques Haynes.

According to the Ben Bolch book, “100 Things UCLA Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die,” Marques Johnson’s 22-inch length at birth prompted his mother, Baasha, to write “UCLA-bound” on his infant photo.

His parents believed in the power Jackie Robinson once achieved at the West Coast school. Both were school teachers, and Baasha earned a Masters in library science from USC. The family purposefully moved to South L.A., much closer to UCLA, when Johnson was 7, as he was already experiencing racism and segregation.

Jeff Johnson put his son into tournament games for 9- and 10-year-olds at Sportsman’s Park in Inglewood. When the family moved to Windsor Hills, an area of Los Angeles considered more upper class for African American families, he was in elementary school with future NFL star James Lofton.

When Marques Johnson arrived at Crenshaw High, Jeff Johnson was an assistant under Willie West. Johnson averaged 26.4 points and 18 rebounds a game for teams that went 32-0 in his last two seasons. Johnson easily took the honors of L.A. City 4A Player of the year in 1973. He did it wearing No. 35 — he admired UCLA’s Sidney Wicks.

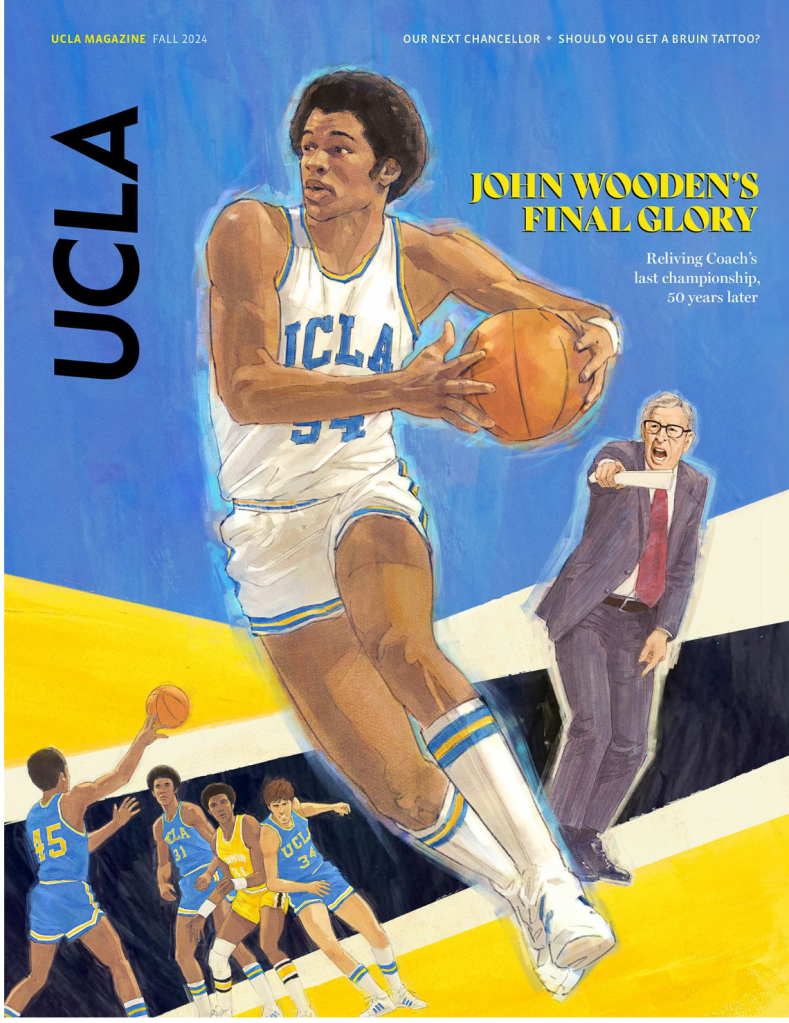

For a UCLA magazine story recalling the 50th anniversary of Wooden’s last title run, Johnson remembered how he had been in the den of his parents’ house and just watched on TV how Bill Walton score 44 points in UCLA’s 1973 championship game win over Memphis State.

“And the phone rings about 10 minutes after the game has ended. My dad answers the phone and says, ‘Poppa Stoppa’ — which is what he called me —‘it’s for you.’ I said ‘Hello,’ and the other end says, ‘Marques, it’s Coach Wooden.’ I’m kind of shocked, you know, jumping out of my shorts.

“I say, ‘Hey, Coach.’ ‘You watch the game, Marques?’ ‘Yes, yes, yes. Congratulations. Congratulations.’ ‘You think you might want to be a part of this next year, Marques?’ ‘Coach, I would love to be a part of it.’ ‘We’d love to have you, we just wanted you to know that. Have a great day.’I hung up the phone, mouth wide open.”

It didn’t hurt that Johnson had impressed UCLA recruiters by scoring 36 and 29 points in back-to-back games Crenshaw High had played at Pauley Pavilion in the L.A. City championship tournament.

Since freshman were now eligible to play basketball and football in college, the 6-foot-7 forward Johnson spent his first year (‘73-’74) in the Pac-8 playing 27 games on a team led by seniors Walton and Keith Wilkes, plus junior David Meyers. Johnson scored 16 points to go with four rebounds in his first start on Jan. 26, 1974 against Notre Dame at Pauley Pavilion. He averaged 7.2 points (fourth best on the team) and 3.3 rebounds a game. That 26-4 squad also had freshman Richard Washington with Johnson to build on.

“At the time basketball had been so easy for me for so long … but coming here wasn’t like that,” said Johnson, recalling how he was guarded by Wilkes in his early practices and wasn’t able to get a shot off for a whole week. “I kind of had to earn my stripes and pay my dues initially.”

As a sophomore on the 28-3 team that won Wooden’s final NCAA title, Johnson’s 11.6 points and 7.1 rebounds a game were third in each category behind Meyers and Washington.But that season was tough for Johnson, who lost 20 pounds as he contracted hepatitis that season.

“I was under orders to work myself back slowly,” Johnson told the L.A. Times, “and I was real frustrated. So one day in practice, I came down on a fastbreak and I dunked hard on Ralph Drollinger, just to get my anger out. Two plays later, Gavin Smith, he came down, he was a great athlete, and he did the same thing, dunked the ball on Drollinger. Coach didn’t say a word to me but he jumped all over Gavin, told him if he ever did that again he’d get kicked out of practice.

“It wasn’t until several years later that I realized what coach was doing. He knew I was feeling bad and he sympathized with what I was going through. He realized I dunked out of frustration and Gavin was just flaunting his talent.”

Wooden’s squad may not have been as deep as his other nine national title teams, but it beat Kentucky, 92-85, in the national championship game at San Diego using just six players. Four of them — Meyers, Washington, Andre McCarter and Pete Trgovich — played all 40 minutes of the title game. Johnson scored six points on three of nine shooting in 24 minutes. Drollinger played the other 16 minutes when Johnson sat and had 10 points off the bench.

Johnson and his UCLA teammates learned after the NCAA semifinal win over Louisville that Wooden would be retiring after the title game.

“It was just a total shock,” Johnson said. “It was total disbelief. We sat in that locker room filled with all sorts of emotions. We were giddy because we had just won this amazing overtime game (over Louisville) and totally sad because coach wasn’t coming back. And there was this great pressure for a minute because nobody wanted to be the player on the team that lost Coach Wooden’s final game.”

The next season, playing under Gene Bartow, Johnson’s junior year saw him average 17.3 points, 9.4 rebounds and 2.5 assists. That 1975-76 team full of Wooden recruits went 25-7 and finished ranked No. 5, with Johnson as a second-team All-American. UCLA made it to the national semifinals, losing to eventual champion Indiana and Kent Benson.

By the 1976-77 season, another NCAA rule change benefited Johnson — it reinstated the dunk after a 10-year ban.

Johnson knew his senior season was going to change a lot. And welcomed it.

“My trainer, Malek, told me, ‘Since people haven’t seen it for a while, we’re going to work all summer on dunking’,” Johnson said. “We did drills where he had me dunking over and over. My senior year, I had 63 dunks! I won the first John Wooden Award partly because of the dunk — a shot that Coach Wooden didn’t care for.”

And now Johnson could own it.

(Flash forward to when Pauley Pavilion closed for renovations, and Marques Johnson was invited back to record the first dunk at the new facility on his 56th birthday in 2012):

The thing is, Johnson almost didn’t play at UCLA as a senior. He applied for the NBA Draft, and there was a report the ABA’s Denver Nuggets were dangling an offer of five years and $1 million.

Neither happened.

The Nuggets became strapped for cash as part of a pending deal to be absorbed by the NBA, and they rescinded the offer. Johnson pulled out of the draft just hours before it happened.

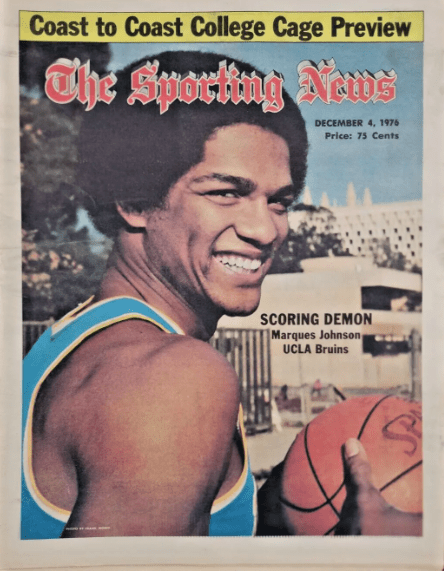

Nine players on UCLA’s ’76-’77 squad would eventually make it to the NBA. Johnson led them all averaging 21.4 points and 11.1 rebounds a game to earn consensus All-American status. The 1,659 points were the most scored by any forward in school history (considering the likes of centers Lew Alcindor and Bill Walton and guard Gail Goodrich came before him).

Along with the inaugural Wooden Award as the nation’s top player, Johnson was bestowed the Naismith Award, the Adolph Rupp Trophy, and Player of Year by the AP, UPI, USBWA, The Sporting News and the Helms Foundation.

But no national title. Or even the Final Four.

The Bruins lost the West Regional semifinal 76-75 to Steve Hayes and Idaho State.

The Milwaukee Bucks had the first and third overall picks in the 1977 NBA Draft, two years removed from trading Kareem Abdul-Jabbar to the Lakers and continuing a rebuild. They took Johnson with the second of those choices; Indiana center Benson was their No. 1.

As both Benson and Johnson wore No. 54 during their esteemed college careers, Benson had first choice to keep it. And he did. Johnson went with No. 8 — he was born on Feb. 8, 1956. It became part of his identity — he is @olskool888 on Twitter.

Johnson far exceeded Benson’s NBA shelf life, beginning with his runner-up to Walter Davis as the 1978 NBA Rookie of the Year. The next season, Johnson was third in the NBA in scoring (25.6 points a game) and named All-NBA First Team. Johnson made four NBA All Star teams in his first seven seasons with Milwaukee.

Averaging 21 points, seven rebounds and three assists made him become the league’s first acknowledged point-forward, long before LeBron James was considered the prototype for the role.

Just before the 1984-85 season, after helping the Bucks get to back-to-back Eastern Conference finals, Johnson was traded by Milwaukee coach and GM Don Nelson along with Junior Bridgeman and Harvey Catchings to the Los Angeles Clippers for Terry Cummings, Craig Hodges and Ricky Pierce.

Johnson had a substance abuse issue in 1982 that led to treatment at a drug rehab facility. His time in Milwaukee was somewhat what Alcindor experienced years earlier.

Keeping No. 8 back in L.A., Johnson’s only real productive season during his three with the Clippers was when he was moved from forward to guard and, in ’85-86, averaged 20.3 points, 3.8 assists and 5.5 rebounds, making the NBA All-Star team. Coach Don Chaney named Johnson the Clippers’ captain, and he was also the NBA’s Comeback Player of the Year.

His comeback was derailed again, just 10 games into the ’86-87 seson when he ruptured a disk in his neck running into the midsection of teammate (and the king of No. 00) Benoit Benjamin during a game in Dallas. Johnson’s parents, Jeff and Baasha; his wife, Jocelyn, and Ed Waters, his best friend from high school, were at the game.

Johnson missed the rest of that season as well as the next two years. He was in a contract payment dispute about having his salary paid. The team claimed he was permanently disabled.

Johnson tried to come back for 10 game with the Golden State Warriors in ’89-90 before going to Italy to play out his career.

The five-time NBA All Star and three-time All-NBA selection ended with a scoring average of 20.1 per game, to go with 7.0 rebounds and 3.4 assists. The career scoring average is No. 75 all time on the list, ahead of Hall of Famers such as Bob Lainer (20.7), Paul Pierce (19.6) and Magic Johnson (19.3) in the top 100.

The aftermath

On the 30th anniversary of Wooden’s last NCAA title, Marques Johnson said in 2005 he was constantly reminded about things the coach taught him.

“I’ve got five kids,” Johnson said, “and they’re all looking for discipline and direction, the basic lessons of life. Coach Wooden can teach those as well today as he did 30 years ago.”

Growing up indoctrinated into the culture of Lakers basketball through his enjoyment of listening to broadcaster Chick Hearn, Johnson had some vague ideas he could get into that talking business when his playing days ended.

“When I was little, I set up my own little basketball court, cut out little cardboard rims and tape ‘em against the wall of my room, clip out the stats of every game from the L.A. Times, so I’d do my Chick Hearn, rapid-fire play-by-play,” Johnson explained once.

“When I got to UCLA, I had a professor who started a sportscasting class. He wanted some of the athletes to participate. So myself and a couple other guys who made it in the NFL, we all took the class. It really opened up my eyes to the possibilities, and I had such a great time doing it.”

His theater arts degree could be put to some use with TV work as he was back in L.A. working on Clippers games. Honestly, it took a lot of acting chops to prove you were invested in winning with that organization.

Johnson said it was the drama classes in the seventh and eighth grade when acting took hold, and it was “really my first love” as he played Conrad Birdie in a production of “Bye, Bye Birdie,” for example. His roles in “Love and Action in Chicago,” “Blue Chips” and “Forget Paris” kept him active in movie roles.

So do his annual attempts to show he can still dunk — or is that alter ego Raymond?

Johnson’s visibility remains as a TV analyst — after years on Clippers games, he worked in Seattle and remains a big deal in Milwaukee. He was also a prominent voice on UCLA radio basketball calls — and was there to chant “Oh, yeah!” as the Bruins won the 1995 title with his son Kris on the roster.

Johnson was inducted into something called the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame in Kansas City (it opened in 2006, he entered in 2013), into the Pac-12 Hall of Honor in 2008, and the California Sports Hall of Fame in 2019.

But he still awaits any invite to being honored by the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield, Ill. He has been on the finalists list several times, most recently in 2024.

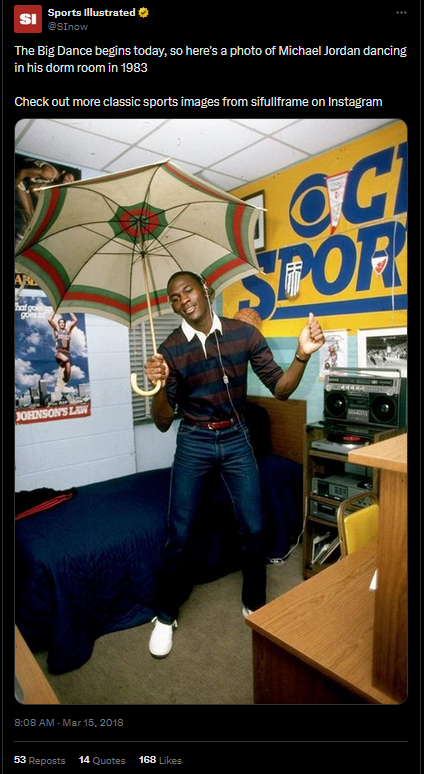

Consider him the original MJ. There’s also some street cred in that, turning back the clock, Marques Johnson was an inspiration a poster hanging in Michael Jordan’s dorm room at North Carolina.

The generational talent

When UCLA retired Marques Johnson’s No. 54 in 1996 — the ceremony included Johnson’s idol Wicks, guard Walt Hazzard and Ed O’Bannon — the school wanted to make sure that the players currently wearing those numbers were going to have to find something new.

Except for No. 54. It was worn by Marques’ son, Kris. The provision was that Kris could keep it.

Kris Johnson’s birth in July of 1975 was four months after his dad played on Wooden’s final NCAA title team. The circle of life had already started.

In 1987, 12-year-old Kris was put in charge to watch his younger brother. The tragedy was that Kris had to watch 15-month old Marques Jr., accidentally drown in the family pool in Bel Air. Kris was so distraught he contemplated suicide. He moved to Atlanta to be with his mother, ended up in juvenile court and was kicked out of school. He moved back with his dad in L.A.

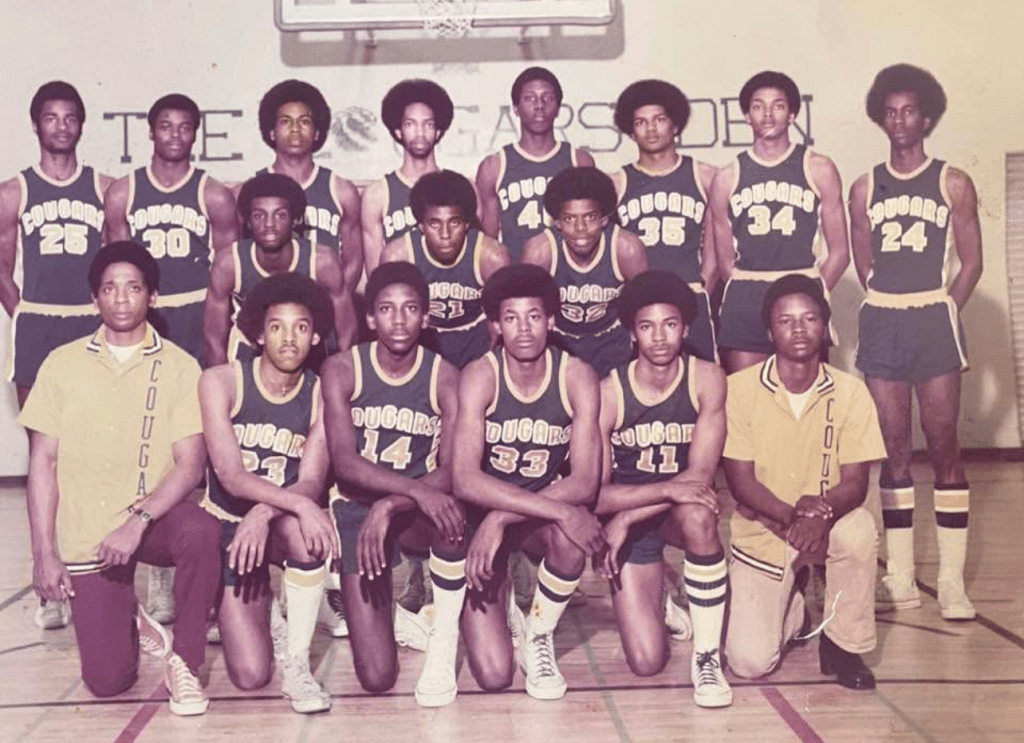

After playing for two years at the private Montclair Prep in Van Nuys, Kris transferred to his father’s alma mater, Crenshaw. It was deja vu. He averaged 22.6 points and 14 rebounds as a junior, and led the Cougars to the L.A. City 4-A title, garnishing player of the year award. As a senior, he came back and averaged 23.3 points and 9.2 rebounds. But it wasn’t a smooth ride. Kris was also associated with gangs at Crenshaw in the Crips territory, once shot at from the rival Bloods group.

A natural to go to UCLA, the 6-foot-4 Kris Johnson made it through 112 games in four seasons from that 1994-95 title team through 1997-98. He averaged 11.6 points, 3.7 rebounds and 1.2 assists. As a junior, he led the team with an 83.5 free throw percentage.

His final season scoring 18.4 points a game (21.1 in conference play) was second-best on the Steve Lavin-coached Bruins. Johnson’s 5.1 rebounds a game was third-best on a team that included seniors J.R. Henderson and Toby Bailey, junior center Jelani McCoy, plus freshman guards Baron Davis and Earl Watson. Those five got a sniff at an NBA career. Johnson, the UCLA team co-MVP, did not, so he went on to play overseas for seven seasons, winning the Asian Basketball Confederation Championship Cup in 2002.

Josiah Johnson, born in 1982, became a 6-foot-8 forward born who also played basketball at Montclair Prep where, as a senior, he averaged 24.2 points, 12.5 rebounds and 2.0 blocked shots a game, scoring 30 or more points five times. He also played two seasons of varsity tennis.

At UCLA, Josiah wore No. 54 in his five seasons from 2000-01 to 2004-05. He only started two games and had career marks of 1.3 points, 1.6 rebounds and 0.2 assists in 56 games. At the end of two of his seasons, he was given the UCLA Alumni Association Award for academic achievement and team contribution.

Josiah Johnson, aka @KingJosiah54, was able to incorporate the number to help claim some interesting notoriety: He became known as the NBA Twitter “meme king” from his home in Woodland Hills. He has been called the GOAT of his craft by LeBron James.

“I just want no frills in how I operate and move,” Josiah Johnson told the New York Times in 2021. “At the end of the day, social is what the name implies — just being social. How would you talk to your friends normally? Would it be a whole elaborate setup? No. It’s just a phone wherever you’re at, and being able to use that technology to be able to communicate with the entire world.”

He also told the L.A. Times in 2022: “It’s like a drug. It’s a great, refreshing feeling to know that something that was in your brain — that didn’t exist previously, that you put out — just takes off and skyrockets. But it’s also a drug where, if you do it enough, it becomes less and less powerful and now I’m constantly chasing that fix again; I want to get that next thing.”

Moriah Johnson, born in 1991 in L.A., is the third youngest of eight siblings fathered by Marques Johnson.

The 6-foot-4 small forward was a straight-A, four-sport athlete at Crenshaw High. As a sophomore, he auditioned as a cast member of the BET reality TV show “Baldwin Hills.”

Enrolling at Tuskegee University in 2011, Moriah Johnson played on the basketball team, wearing Nos. 32, 44 and 13 and also ran cross country as a senior in 2013.

Another son, Joshua, who goes by J. Marques Johnson, or Joshua M., or J. Marquez, has also carved out a career in acting.

In 2024, Marques Johnson saw his 15-year-old daughter, Shiloh, a 6-foot freshman, start playing on the varsity team at Windward School in Mar Vista. She wore No. 13.

But when it comes to a third generation of talent, there was Will Johnson.

The 6-foot-1 guard — son of Kris Johnson, grandson of Marques — spent two seasons at the University of Oregon (2018-19 and 2020-21) before transferring to Humbolt State (2021-22).

The story goes that as a 13-year-old freshman, Will tried out for the Palisades High squad, made the JV team and barely played. Kris saw his son’s discouragement, but he could understand it as the son of one of the sport’s best-known talents.

Will was not a knockoff of Kris, just as Kris was not a knockoff of Marques.

“You’re not a real Louis Vuitton or a real Fendi bag,” said Kris. ” You, you know, look like one, but you’re not one. And that’s kind of how I felt a lot with people. The pressure, it manifests itself to where it makes you feel lesser than, it messes with your confidence. It gives you a kind of a skewed or altered view of what success is.”

Will Johnson admitted he “wanted to uphold the family name” and became the Western League’s Most Outstanding Player as well as well as earning L.A. All-City first team honors by his senior year at Palisades.

“It used to be a lot of pressure,” Will said. “I wanted to be on the same level as them. … But I realized as I got older, I’ve just got to be me.”

Will went to Oregon as a walk-on, earned a scholarship and learned to be a reserve on a talented Pac-12 team.

“Just to see him on the bench,” Kris said, “just to get a glimpse of that curly top and his little chin-strap beard he’s got going … I’m just proud constantly of the kid.”

When Will began his Oregon career, director of operations Josh Jamieson asked what jersey number he wanted.

Of course, No. 54.

“Of course, it would be amazing and super cool if I were to live up to,” Will said. “I mean, I think I have lived up to the family name.”

Who else wore No. 54 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

Larry Farmer, UCLA basketball forward (1970-71 to 1973-73):

A UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame inductee in 2018, the 6-foot-5 forward was on three straight NCAA title teams and experienced an 89-1 record in his three seasons after earning the Bruins’ freshman squad MVP in 1969-70, leading them with 21 points and seven rebounds a game. In six years as an assistant coach with the Bruins, the team was 144-34, winning four league titles and went to the 1980 championship and 1976 Final Four. Given a chance to be the head coach in 1981, and the first African-American given the role, he guided the Bruins to the 1983 Pac-10 title and had a record of 61-23 in three seasons. His autobiography, “Role of a Lifetime” came out in 2023.

Kenny Fields, UCLA basketball forward (1980-81 to 1983-84), Los Angeles Clippers (1986-87 to 1987-88):

Out of Verbum Dei High in South L.A., where he led the team as a Camino Real League MVP and two-time All-CIF star averaging nearly 25 points a game, Fields was thought to be going to play for Jerry Tarkanian at Nevada-Las Vegas. “We had Kenny Fields coming out way, then Sam Gilbert entered the picture,” Tarkanian said in 1980 about the UCLA super-booster. “I’ll tell you, when they build a hall of fame at UCLA, they better put Sam Gilbert in there. He’s No. 1.” At UCLA, Fields averaged double digits in scoring all four seasons. His final two seasons of 18.0 and 17.4 points a game lifted him to a No. 21 overall draft pick by the Milwaukee Bucks in 1984. Field would wear No. 54 with the Clippers as a teammate for one season with former UCLA star Marques Johnson.

Horace Grant, Los Angeles Lakers forward (2000-01 and 2003-04):

His connection with Phil Jackson and the Chicago Bulls resulted in the coach recruiting the defensive specialist to L.A. as a starter in 2001 and a backup to Karl Malone in 2004. In his first run, he started 77 games and helped the Lakers on a 15-1 playoff run to the team’s third straight NBA title. Coming back wasn’t so eventful as he was left off the post-season roster. But he and Ron Harper have a common distinction: They are the only two to be on an NBA title team with both Michael Jordan and Kobe Bryant.

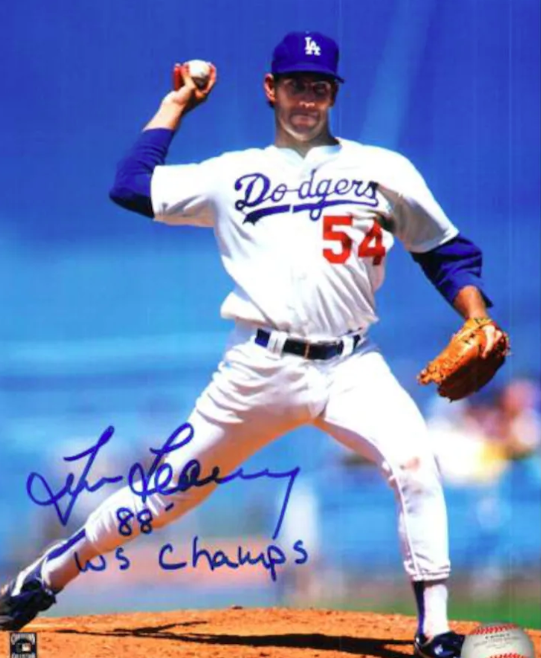

Tim Leary, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1987 to 1989):

The Dodgers’ 1988 World Series title team was identified by Kirk Gibson’s bat and Orel Hershisher’s arm, but Leary had a career-best 17 wins on the mound — as well as coming off the bench as a pinch hitter. A Santa Monica High and UCLA All-American, Leary came back to L.A. before the ’87 season. The Dodgers gave up on prospect Greg Brock and needed pitching, so it went to the Milwaukee Brewers for Leary and reliever Tim Crews. Leary wore No. 23 when he posted a 3-11 record as a spot starter and reliever in his first season. In the off season, he built up his arm pitching in the Mexican League, posting a 9-0 record and 1.24 ERA with a new split-finger pitch. Giving up No. 23 to Kirk Gibson and switching to No. 54 for 1988, Leary had career-bests with 228 innings, a 2.91 ERA, nine complete games and six shutouts. He was named the Sporting News Comeback Player of the Year. Leary, the No. 2 overall pick in the New York Mets in the 1979 draft out of UCLA, was was inducted into the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 1991 and became a pitching coach on the Bruins’ staff as well as at Cal State Northridge.

Have you heard the story:

Edgar Lacy, UCLA basketball forward (1964-65 to 1967-68), Los Angeles Stars (1968-69 to 1969-70):

Can one become famous enough to finally tell the newspaper guys they have been misspelling his name for years? The L.A. Jefferson High star named L.A. City Section Player of the Year, Mr. California Basketball in 1963 and a two-time first-team Parade All American — one of the greatest high school hoop stars in L.A. history — had constantly seen his last name written as “Lacey.”

It even stayed that way when the 6-foot-6 postman went to UCLA and helped the Bruins to the 1965 national title. In a 62-game career, Lacy averaged 12.2 points and 9.3 rebounds a game — missing the ’66-’67 championship season with an broken kneecap injury and declining a chance to join the Boston Celtics as a draft pick. Lacy instead returned to UCLA for his official red-shirt senior season, but he only played the first 13 games (all wins), including the famous UCLA-Houston game at the Astrodome. Lacy quit after that contest in a dispute with coach John Wooden, who took him out of the game for his inadequate defense on Houston star Elvin Hayes.

“(That) was the last straw,” Lacy said of Wooden’s tutelage. “It all started in my sophomore year when he tried to change the mechanics of my shooting. And now I have no one to blame but myself for staying this long. He has sent people by to persuade me to reconsider, but I have nothing to reconsider. I’m glad I’m getting out now while I still have some of my pride, my sanity and my self-esteem left.”

It wasn’t until he signed his first pro contract with the Los Angeles Stars of the ABA — which outbid the NBA’s Los Angeles Lakers — that Lacy corrected everyone: His name was spelled without that “e” before the “y.” He wore No. 22. Some still couldn’t get it correct.

Lacy only played the one year of the ABA, averaging 5.1 points and 3.9 rebounds in 46 games, then left to go back to school to get a law degree. A 2011 story about Lacy at the time of his death at age 66, as he was to be celebrated at a church in Downey, sealed how he would be remembered: “Basketball star who lost his shine in 1 night.”

The story added an “e” in Lacy’s last name.

The 1963 All-American High School Basketball Team appears on The Ed Sullivan Show on March 31, 1963. It includes Lew Alcindor, left, and Edgar Lacy, right.

José Ureña, Los Angeles Angels pitcher (2025):

Eureka: This become a three-player entry based on the fact Ureña, Mike Baumann and Oliver Drake share a unique MLB/DFA resume designation having played for five MLB teams in one season. Each also came to play for the Angels as one of those five employers. And, they’re all right-handed relievers.

Ureña, from Venezuela, was handed No. 54 by the Angels on Aug. 31, 2025 with the expectation he could help finish up the going-nowhere season. He had just been pitching for the Los Angeles Dodgers’ revolving door bullpen during a 10-day stretch from June 3 to 13, wearing No. 47, which covered three innings in two appearances. Also in 2025: the New York Mets, Toronto and Minnesota. The New York Times caught up with him to make sure he knew which locker room he belonged in.

“It’s not fun, but at the end of the day, it’s business,” Ureña said. “They can control it. They’re looking for some player; they want to put you out. But you’ve got to keep pushing.”

In 2024, the Times also caught up with Baumann. That season he, started with Baltimore, Seattle and San Francisco, ended with Miami, and had two weeks sandwiched in there with the Angels, wearing No. 53. That covered 10 appearances from July 31 to Aug. 22. He went to Japan to pitch in ’25.

Drake, in 2018, has been the only other five-timer. For the Angels, wearing No. 36, he made eight appearances from June 1 to July 21 and stuck around long enough for an 0-1 record and 5.19 ERA. He started that season in Milwaukee and Cleveland, finished with Toronto and Minnesota, and before the calendar year ended, went to Tampa Bay.

Mark Lansburger, Los Angeles Lakers forward (1979-80 to 1982-83): His two NBA titles with the Lakers may be considered slightly more earned value than the two Adam Morrison received in his abbreviated career. But the 6-foot-8 power forward may best be remember by the reporters who covered the team for the story involving him at a team autograph session. One time, Lansburger was asked by a fan to write his number underneath his autograph. You’d think he meant the jersey number? Lansburger wrote his phone number.

Clayton Kershaw, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2008): As noted in the bio piece that comes with Kershaw in the No. 22 post: He wore No. 54 in his MLB debut on May 25, 2008 just a few months past his 20th birthday. Teammate Mike Sweeney, who appeared in the game as a pinch hitter, saw the writing on the wall. Kershaw wanted Sweeney’s No. 22, because Kershaw grew up in Dallas idolizing Texas Rangers first baseman Will Clark (who also wore No. 22 during his days in San Francisco). Sweeney, in his 14th and final Major League season and his second with the Dodgers, told the Los Angeles Times on giving Kershaw No. 22 and then taking No. 21 for himself: “ (He is) going to be in this uniform for a long, long time. It’s something important to do from an organizational standpoint.”

We also have:

Kwame Brown, Los Angeles Lakers forward (2005-06 to 2007-08)

Jack Haley, Los Angeles Lakers center (1991-92)

John Candelaria, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1991 to 1992)

Ervin Santana, California Angels pitcher (2005 to 2012)

Mike Wilcher, Los Angeles Rams linebacker (1984 to 1990)

Melvin Ingram, Los Angeles Chargers defensive end (2012 to 2020)

Anyone else worth nominating?

2 thoughts on “No. 54: Marques Johnson”