“Baseball’s Best (and Worst) Teams:

The Top (and Bottom) Clubs Since 1903“

The author: G. Scott Thomas

The details: Niawanda Books, 586 pages, $24.99, released March 4, 2025; best available at the publishers website and Bookshop.org.

A review in 90 feet or less

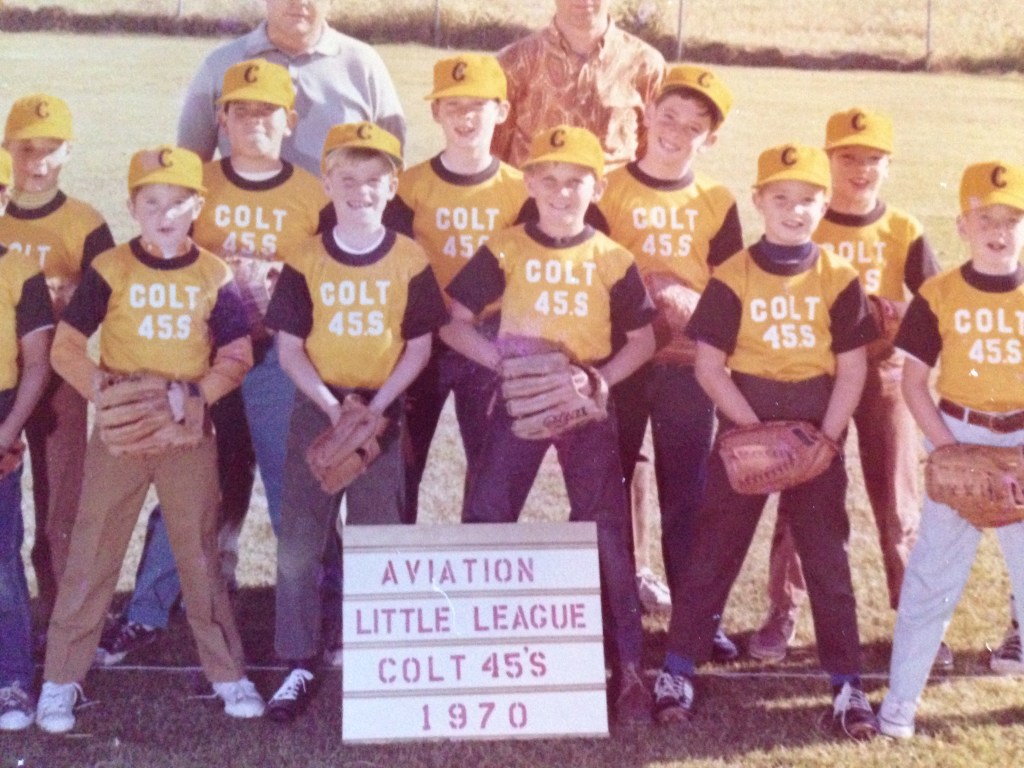

Take a look at what could very well be the greatest baseball team ever assembled.

Fifty-five years ago, the 1970 Aviation Little League’s Colt .45s were drawn together as one the most well-intentioned and ill-informed 9-and 10-year olds from the Del Aire adjacent neighborhoods of Hawthorne, California.

It was the first organized baseball team that allowed me to be included. It was the greatest.

So maybe the last vestige of evidential proof of our existence has the coaches’ heads cropped off at the top and another kid aced out on the left side. Not sure how that happened. But I made the cut — second from right, back row, wearing brown hiking boots because my family was heading on a camping trip and delaying it to meet up at the ballfield for this team shot couldn’t have ended soon enough to beat the out-of-town traffic on a Saturday morning.

We may have been the bearers of bad news a few years before “The Bad News Bears” were even a thing somewhere over in the San Fernando Valley. We also really no clue what our nickname even meant. It had been abandoned by the MLB’s Houston franchise five years earlier, as they were branded during their 1962 launch.

Maybe we were just old school and didn’t know it. Was it paying homage to old-time Wild West gun play or to a malt liquor?

It was a different time.

The other point to make: When you compare what we had to the actual Houston Colt .45s logo, it became obvious to me even when standing in right field, not paying attention and and looking down at this jersey, something was amiss. Maybe whomever’s mom had to iron on the white felt letters didn’t really know where the period was supposed to go, and it was mistaken for … an apostrophe? Would it have been more prudent to order up some smaller-size “S” after the “45.”

Or, were really just named after the small vinyl records?

With pull-over jerseys that made us look more like Killer B’s, the black sticky numbers ironed onto the back side below the team sponsor — could it have been some local gun shop? — smelled like burning tar when they came out of the clothes dryer. The numbers often melted together. And stunk.

But we didn’t. It is likely lost to history how many games we won, or lost, or had called on account of darkness. Or canceled because the ump didn’t show. We were just focused on which end of the wooden bat to hold and which oversized batting helmet might look the least stupid when we crammed in on top of our caps.

Then again, maybe this group above is the greatest team — the 1980s era of the Daily Breeze’s Young Turks softball dynasty with home games at Wilson Park in Torrance. Real mature scribes. Knew when to end the game because we had a print deadline to meet. And with someone bold enough to wear sunglasses and loud Hawaiian shorts in a team photo, along with stirrups and knee pads.

Guilty again.

This looks like the freeze frame final scene of the movie “Diner.” This was our formal attire. And our lineup had to rival the ’56 Dodgers.

Declaring allegiance to one team’s greatness — its place as the most dominant, dynamic, and undeniably distinguished — is one of the baseball’s best gifts to its fans. When the question is applied to Major League Baseball history, you gotta have something locked and loaded to fire back. Show no hesitancy. Bring verisimilitude.

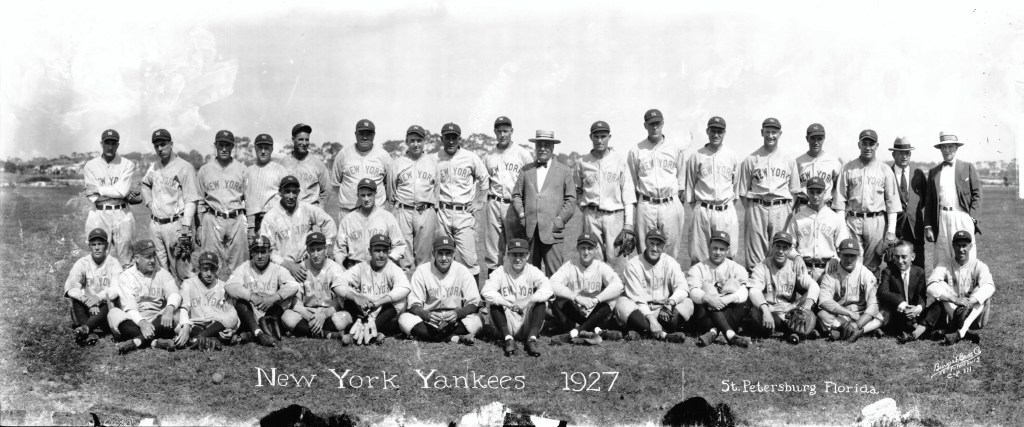

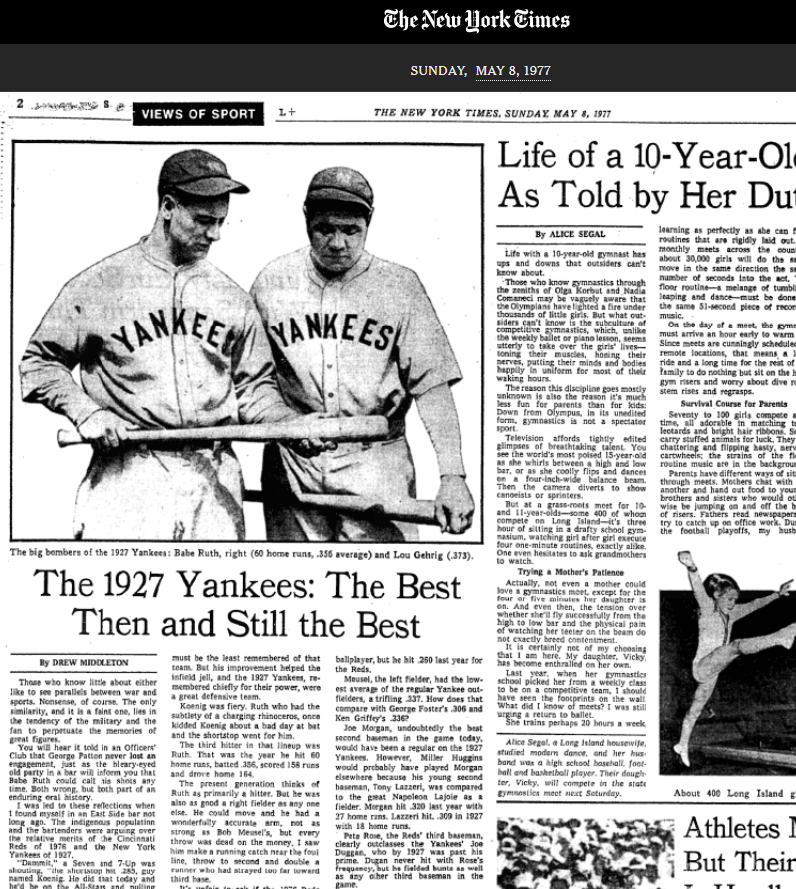

The default answer: The ’27 New York Yankees. (Note: By the time you finish this post, you will have purged that from your acid reflex response. Especially by the time 2027 rolls around).

The honest answer: Our favorites are clouded by regional bias, midunderstood childhood misunderstood, things we are told about cultural significance and illogical mythology. All of that becomes a toxic mix when this devolves into bad-ass barroom banter. Because everyone knows a Norm and a Cliff, and when it comes to the norms of drinking beer and having an argument, this whole thing can veer off a cliff.

The quantifiable answer started with doing some homework. Concoct the appropriate historical data translatable to current software, shape it in any way that supports an argument. Then prepare to be able to defend your honor.

G. Scott Thomas gives us that graceful exit with a 580-page paperback that weighs in at about two pounds of pulsating pulp, and it shows all his work. It’s an expansion of that he did in 2016 (then 486 pages).

Thomas’ thought-provoking research caught up with us during the launch of his 2023 book “Cooperstown at the Crossroads: The Checkered History (and Uncertain Future) of Baseball’s Hall of Fame,” which became the first book we reviewed that season.

The “Great Scott” moment this time is how he manipulated history and logic to responsibly analyze the 2,544 American and National League teams that comprised every season of the World Series era starting in 1903 — minus those years bastardized by one thing or another in 1904, 1981, 1994 and 2020 and account for a quarter of the Dodgers’ eight franchise World Series winners.

Assigned with a numeric value based on a rather thought-out formula that we trust is fair and just, the scoreboard tells the story when the decimals settle.

“Yes, the ’27 Yanks deserve to be ranked among baseball’s great teams,” Thomas writes. “But, no, they weren’t the very best of all time.”

A little backtracking:

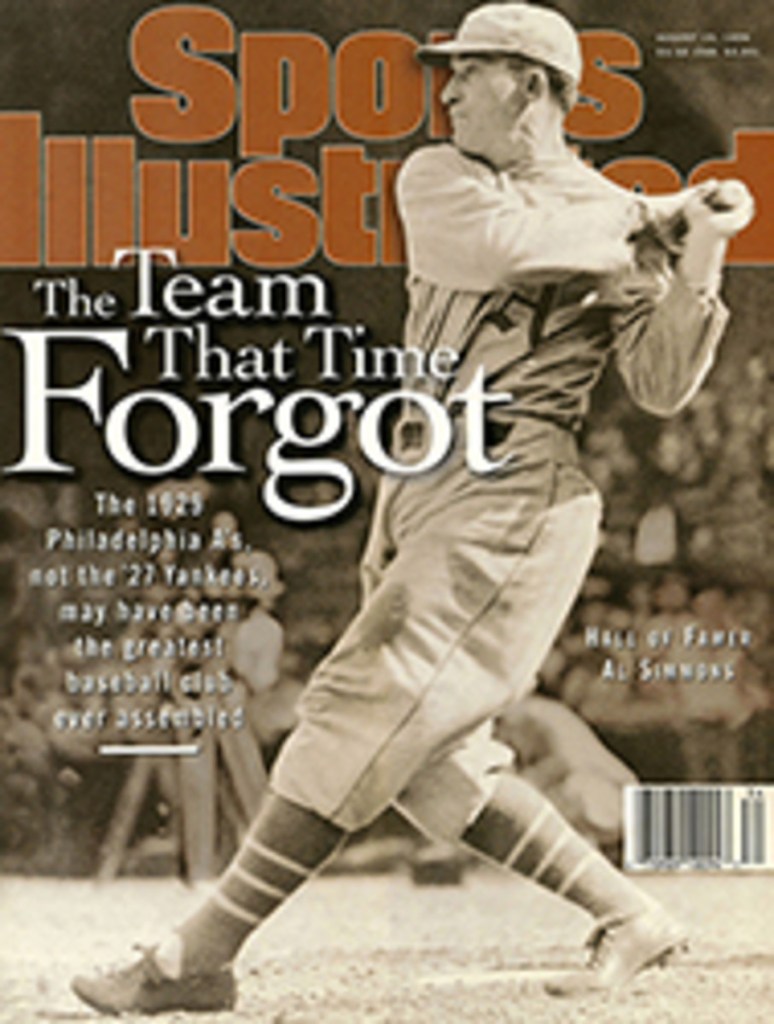

In 2000, SABR guys Chris Holaday and Marshall Adesman honed on determining who they felt were the “25 Greatest Baseball Teams of the 20th Century” for a McFarland publication.

After they singled out 25 teams for superior achievement, they then offered their own personal ranking — Holaday latched onto the 1929-to-’31 Philadelphia Athletics as the overall greatest, followed by the 1975-’76 Cincinnati Reds; Adesman came up with the 1936-to-’39 Yankees ahead of the ’49-to-’56 Dodgers (which Holiday ranked No. 6).

This feels a little too loose around the definite. A focus on a franchise’ era rather than a single team maybe defeats the purpose, even if there was little player movement prior to the ‘70s free-agent implementation. Still, it shows neither were sold on any Yankees’ murderous teams from the ‘20s.

Five-Thirty-Eight tried their own flawed logic in 2015, ranking 2,374 team-seasons, also starting in 1903. They declared the 1906 Cubs have “the highest peak Elo, but because of their World Series loss, they rate as the second-best team since 1903, behind the 1939 New York Yankees.” It’s their guide-rails, so be it. Still, it’s not the ’27 Yanks.

In 2023, Baseball Prospectus did its own “101 Most Dominant Teams of All Time.” It landed on the 1998 New York Yankees, followed by the ’27 Yankees, the ’39 Yankees, and the ’36 Yankees.

Anyone beside the Yankees, be dammed.

Earlier this month, in what might be considered something of an addendum to the Holaday-Adesman project, Gabe Lacques of USA Today compiled his rankings of World Series winners since 2000. He earmarked the 2018 Boston Red Sox, which outlasted the Dodgers in the Fall Classic, as the best so far this century. It should be noted that Dodgers eventually extracted Mookie Betts along with David Price and Joe Kelly from that team, maybe to make themselves feel better afterward.

The Dodgers’ bastardized 2020 COVID winners were ranked eighth, ahead of the Dodgers’ 2024 champs at No. 11. The Dodgers’ 2017 team — keep that in mind for future reference — didn’t qualify on this list (see: Astros, trash-can banging, title run).

For those OC curious: The 2022 Anaheim Angels, whose 99-win season still left them as a wildcard out of the AL West, were No. 17.

Circle back to Thomas.

Leaning into the accurate premise that the ’27 Yankees shouldn’t actually be everyone’s default answer — or, if it is, quantify why — cites several media platforms (The Sporting News, Bleacher Report , ESPN and Yahoo Sports) that have perpetuated the team surprise (and see our find of the New York Times).

“Baseball people willingly fight about anything and everything,” Thomas writes. “Opinions abound; harmony is rare. But there appears to be one exception, one instance of this quarrelsome community arriving at a virtual consensus.”

Without citing data at first, Thomas shows evidence that ’27 Yankees were a well-crafted creation of the New York media to a point where they were an easy fallback punchline. The roster anchored by “demigods” Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, and a “Murders’ Row” that won it all again in ’28, likely overshadowed the fact the rest of the squad wasn’t really all that extraordinary (despite some Hall of Fame plaques that may argue otherwise). There’s also the indisputable data that shows athletes have progressively become bigger, stronger and faster since the Loutish ‘20s. The competition has expanded and become more demanding, creating a far more difficult gauntlet to maneuver in a title run. So while the talent pool has depend, it’s not just the addition of more African Americans by the 1950s, but it’s a global market to choose from.

In promoting what he wants to accomplish with the book, Thomas offers a litany of quotes over the years on the back cover, attached to certain teams, many of them subjective of recent bias. Such as:

“Nineteen twenty-seven, that was the club. We had everything.” — Lou Gehrig, first baseman, 1927 Yankees

“This was a team that simply never made a mistake.” — Sandy Koufax, pitcher, 1955 Dodgers

“I wonder if people realize what a great team we have?” — Pete Rose, third baseman, 1975-1976 Cincinnati Reds

“People will look back on this team as truly the greatest of all time.” — George Steinbrenner, owner, 1998 Yankees

Thomas gets the last word in, because he can:

“All hail the 1984 Detroit Tigers, the greatest team in baseball history. Surprised? I’ll bet you are.”

There’s your spoiler alert.

The journey to how Thomas decides this becomes the book, and it expands to include all sorts of breakdowns — per franchise, per decade, as well as a thorough assessment of teams over the years that make up his Best 100 and Worst 100.

Thomas is thankfully self-aware enough to not over-explain the formulas that might bog things down, yet the 30-some pages that explain the “technical stuff” comes off as very Bill Jamesian.

The most intriguing hypothesis Thomas concocts is a reaction to how absurd he believes that the OPS stat us used with such authority, because it is flawed in taking one statistical category — on base percentage, with a ceiling of 1.000 — and then adds it to another stat — slugging percentage, with a ceiling of 4.000. Now you have something that any middle-school math whiz can figure out doesn’t mean anything because you have uncommon denominators with these fractured fractions.

His answer is a stat called BPO — bases per out — to eclipse OPS and become the third leg of his four-point formula that determined how close a team comes to a score of 100. That can quantify the quality of the roster. The other standards are team winning percentage during the regular season, team run differentials, and team postseason success. This comes into play so that if a team didn’t win a World Series (such as the 2017 Dodgers), it could pencil out as a better team on paper than one that did (such as the 1988 Dodgers).

Factoring in some standard deviations, Thomas assigned the ’27 Yankees with a 91.389 ranking, which only ties them for No. 7 all time with the 1941 Yankees (the DiMaggio-in-his-prime AL MVP winner team that won the World Series over the Brooklyn Dodgers). The ’98 Yankees (114-48 in the regular season, 11-2 in the playoffs) are actually Thomas’ second-best all time (97.965) behind the ’84 Detroit Tigers (98.987).

Interesting to us: The San Diego Padres, currently the NL team that has gone the longest without a World Series title (back to their inception in 1969), made it into two Falls Classics — only to face the No. 1 and No. 2 rated best teams in MLB history, according to these calculations. They really had no chance, did they?

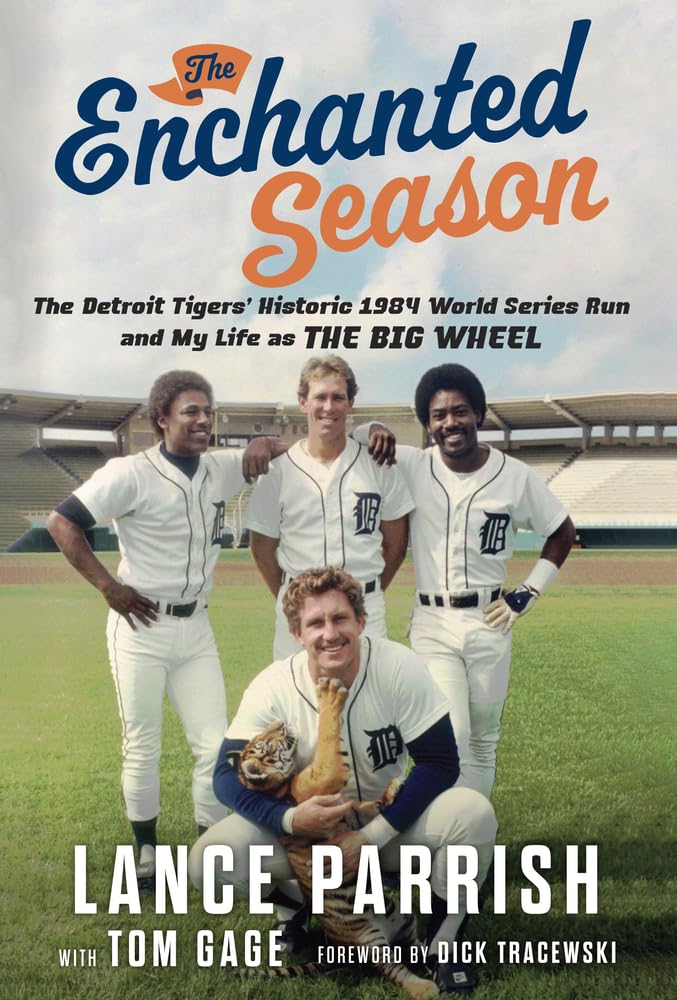

The ’84 Detroit “Bless You Boys” indelible stamp was a 35-5 start and no looking back. It was far more than Kirk Gibson, Alan Trammell, Lance Parrish, Jack Morris and Lou Whitaker — as Parrish will tell you in his 2024 book called “The Enchanted Season: The Detroit Tigers’ Historic 1984 World Series Run and My Life as The Big Wheel” (Triumph Books)

The linchpin was an AL MVP and Cy Young Award winner that sat in the bullpen at the start of teach game — a 29-year-old closer named Willie Hernandez, in his first year in the league after eight seasons with the Cubs and Phillies, who blindsided everyone with a league-best 80 appearances, 68 games finished, 32 saves and a 9-3 mark with a 1.92 ERA. (His SABR bio calls that season “truly astounding,” and it wasn’t edited out by those who reviewed it).

Settling on that ’84 team, which went 104-58 in the regular season plus 7-1 in the playoffs, comes with the fun fact: The Tigers of ’83 (92-70), ’85 (84-77) and ’86 (87-75) failed to make the playoffs with basically the same core roster and manager.

No Dodger teams were harmed in the making of this book — at least none are in the Worst 100. As for the franchise’s representation in the Best 100, it will be the 1955 team that is ranked 18th (88.447). Then comes that 2017 team ranked No. 59 (83.835); ahead of the 1978 team ranked No. 66 (83.379); the 1974 team ranked No. 73 (83.024); the 1953 team that won 105 regular season games ranked No. 84 (82.179) and the 2024 recent World Series winners ranked No. 88 (82.034). Only two of those six teams won a title. Thomas notes in his Top 100, less than 75 percent were declared champions. Conversely, the Dodgers’ title teams of ’59, ’63 and ’65 won despite having what can be called “greatness” — and the 2020 team, as noted, isn’t even evaluated in this exercise.

Among the other quirks Thomas’ digs up:

The Angels’ recently-posted 63-99 season goes down as the worst in their 60-plus year history, while the 99-63 wild-card team that won the 2002 World Series is the best, even though it didn’t win a division title, while nine other Angels team actually did (the last in 2014). Thomas says it is “noteworthy” that no Angels’ teams made it into the Best 100 or Worst 100.

Why this book becomes timely: The team he picked to be most pathetic of all time is one we just saw — the 2024 Chicago White Sox and their 41-121 output (0.881 mark).

Maybe call them the Bleak Sox.

An author Q&A

Q: Are you satisfied, after all this, that people won’t default to the ’27 Yankees as the standard bearer for baseball greatness? Will that be your greatest take-away from this project?

A: Let’s face it. The ’27 Yankees have a head start of 98 years. I have no doubt that they will continue to be hailed as the greatest team of all time. I just don’t believe they deserve the title. They dominated an incredibly weak league, and their lineup had a few substantial holes, especially on the left side of their infield. Were the ’27 Yanks an excellent team? Yes, of course. Were they the best ever? My formula — and my gut — say no.

Q: Before all this research, what was generally your fallback answer to ‘Which team in MLB history is the greatest?’ What team as a kid did you think fit this description and how did that change as an adult?

A: I have to be honest. I analyzed more than 2,500 ballclubs from the entire World Series era, and I simply assumed that the ’27 Yankees would emerge as the overall leader in my final rankings. I had always heard that they were head and shoulders better than everybody else. But that didn’t prove to be the case. The ’27 Yanks did pretty well — my formula ranked them seventh — but the 1984 Tigers were decidedly better, the best overall, in fact. I buttress that point in the book by comparing those two clubs at 11 positions (including the starting rotation, the bullpen, and the bench as three of those positions), as well as their managers. The ’84 Tigers were better than the ’27 Yankees in seven of those 12 cases, with a tie at an eighth. New York was only superior at four positions.

Q: Likewise, who did you sense was the worst?

A: As for the worst team of all time, I just assumed that the infamous 1962 Mets deserved the honor. But the ’63 Mets actually were worse than the ’62 version — and a late entry, the 2024 White Sox, actually ranked as the very worst of all.

Q: Could you, or would you, have advanced this idea of calculating a formula to determine the best and worst teams of all time without your creation of the far-more-reliable Base Per Out formula?

A: I generated a team score (TS) for each club, plotted on a 100-point scale. Each TS was based on a given team’s regular-season record, run differential, BPO differential, and postseason success (if any). So yes, the BPO that you mentioned is part of the formula, but it wasn’t essential. My aim was to use a few basic stats to determine a team’s overall quality, after taking into account the level of competition that the particular club faced.

Q: In the lineage of the books you have written about all sorts of subjects – Presidential elections, rating the life of America’s 50 states as well as the Cooperstown Crossroads – was this topic best to tackle at this moment rather than earlier? Had you been brewing this book for some time now for this moment?

A: I developed the TS formula a decade ago, when I was writing about the best performances by teams and players throughout the expansion era (since 1961). And I have subsequently used it in my online newsletter, “Baseball’s Best (and Worst).” So it just seemed logical to take a look back at the full history of the game.

Q: Did you consider having any kind of writing partner on this to counter any of your data, or fact check, or question its validity, and then create a sort of “argument” book?

A: I come from a journalistic background, where you generally report and write a story on your own, and I approach my books the same way. Just a personal habit, I guess.

Q: The Angels are a team without a single entry in your separate lists of baseball’s Best 100 and Worst 100. Did they at least fall close to the absolute middle of these two lists – maybe ranked No. 1,272nd? Are we to now officially quantify that the Angels are the most numeric purgatory team in the game’s history?

A: That’s a strange thing about the Angels, isn’t it? They’re one of only two franchises that isn’t represented in either the Best 100 or the Worst 100. The other one is the Rays, a considerably younger organization. Every franchise that’s at least 60 years old has at least three entries in the best and worst lists (taken together) — except the Angels. They’ve never gotten too high or too low, I guess. But there is a Los Angeles connection to the midpoint. The 1998 Dodgers just happen to occupy 1,272nd place in the overall rankings.

(Note: That team finished third in the NL West at 83-79 and manager Bill Russell lasted just 72 games, and Tommy Lasorda jumped in as the interim GM in June to muck things up after Fred Claire was let go when the inexperienced Fox execs traded away future Hall of Famer Mike Piazza to Florida for a regional cable rights deal).

Q: What was the key component in your research that you feel kept a Dodgers’ squad that was basically the same in ’59, ’63, ’65 and ’66 from becoming considered greater than they were, as each of those went to a World Series in this eight-year span (and the ’62 team lost in a three-game playoff)? Even in your breakdown of the 1960s, there are no Dodgers teams in the Top 5. Was it somewhat comparable to the 2012 and 2014 San Francisco Giants that won with a rather unimpressive TS?

A: You’re right. There was a similarity to those later Giants, who didn’t exactly blow their opponents away. The biggest problem for the Dodgers of the late 1950s and into the 1960s was their relative weakness offensively. They certainly had the pitching, but their hitting was unimpressive, to say the least. The 1965 and 1966 Dodgers both ranked eighth in the 10-team National League in runs scored, and the ’65 squad was dead last in home runs. The way to accumulate a high TS is not only to win consistently, but to win decisively, and those Dodgers teams simply didn’t do the latter.

Q: Maybe that leads to this question: Are pitching and defense taken into proper account for a great team in all this calculation? Can a team be considered a great one if it relied predominantly on pitching and defense (and speed) if that was a formula that led to success in those time periods?

A: Yes, it can. The two important things, as I just mentioned, are to win consistently and decisively. It doesn’t really matter how you accomplish those two objectives. The 1907 Chicago Cubs, for example, hit a grand total of 13 home runs, which was low even for the dead-ball era, and not one of their everyday players batted .300. But their pitching was incredible, with three starters posting ERAs below 1.50. (The league average that year was 2.46.) And they led the league in fielding. My rankings have those 1907 Cubs (107-45-3, World Series champs) as the 44th best team of all time.

Q: Anything else you weren’t able to get into this book because of time/content you already committed to?

A: No. I put together comprehensive profiles of each of the 50 best teams, as well as the 10 worst, and they really drove the page count up. The book is almost 600 pages long, so I think I covered the topic.

Q: What’s your next project?

A: That’s a good question. I don’t know yet, though I think it will be something other than baseball. It’s always good to change things up.

How it goes in the scorebook

Power in truth triumphs over chimerical truthiness.

Teeming with enjoyment, leaning into the proper data, and well-meaning for those who think things through rather than just react to emotions, this is the proper intervention tool for any Yankee apologist. It automatically ranks No. 1 in any book about ranking the best/worst teams in MLB history because we can’t imagine this one every bottoming out.

It’s a book that should be at arm’s length, especially at all drinking establishments so that a barkeep can grab next to the seltzer spray bottle in the event of a memory-lapse emergency.

You can look it up: More to ponder

== On Thomas’ “Baseball’s Best (and Worst)” Substack account, the March 18 edition uses his history-based prediction system to not only anticipate another NL West title for the Dodgers in 2025 (with Arizona outlasting San Diego for the runner up spot) but also far and away ahead second-best Philadelphia in rating all 30 teams. (To that point, the Dodgers have 190 points in Thomas’ ratings system; the Phillies are next with 128; the Angels are at 34; the Marlins are at 12). His post on March 21 about how the American League will turn out has the Angels finishing a distant fourth in the AL West behind the tight bunching of Houston, Seattle and Teaxs, barely above the Sacramento Athletics, and most comparable to the 2019 Royals (59-103).

== Spotlighting more books in our late ’24/late ’25 range that focus on particularly memorable teams:

= “One More for the White Rat: The 1987 St. Louis Cardinals Chase the Pennant,” by Doug Feldmann, University of Nebraska Press, 232 pages, $34.95; to be released April 1, 2025.

It’s a deeper dive into this particular NL East-winning 95-67 Cardinals’ squad, managed again by Whitey Herzog, that starts out two years earlier with a shocking 101-win NL championship team in 1985 that lost to Kansas City in the “I-95 World Series, followed up by a miserable sub-.500 record in ’86 where Herzog nearly resigned. The comeback of ’87 was focused on “Whiteyball” with Vince Coleman’s 109-stolen-base performance, Jack Clark’s 35-homer production and Ozzie Smith finishing second in the NL MVP race with a .303 average and another Gold Glove. The team, which had three pitchers tie with 11 wins each to lead the rotation and Todd Worrell mopping things up, again fell short in the World Series, losing Game 7 to Minnesota. Herzog actually lasted through the first part of the 1990 season and a 34-47 mark before he was temporarily replaced by Red Schoendienst and then by Joe Torre.

= “1960: When the Pittsburgh Pirates Had Them All the Way,” by Wayne Stewart, Sunbury Press, 264 pages, $22.95; re-released July 2024 from a 2020 first edition.

Yankees fans will contend that Casey Stengel mismanaged this whole shebang. No wonder Mickey Mantle cried. And one home run gets Bill Mazeroski into the Hall of Fame, over forgotten hero Hal Smith. Stewart tracked down every living Pirate to talk about this team. Don’t confuse this with “Sweet ’60: The 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates” by Clifton Blue Parker for SABR publications in 2013, or with “Had ’Em All the Way”: The 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates,” by Thad Mumau for McFarland in 2015.

= “White Sox Redemption: The Road to World Series Victory in 2005,” by Dan Helpingstine, McFarland Publishing, 137 pages, $29.95; scheduled for release in August of 2025.

From the publishers’ blurb: In the past, everything went wrong for these Pale Hose/South Siders, whose history includes the 1919 Black Sox Scandal and the residual effect of Bill Veeck and Disco Demolition Night in ’79. The only World Series appearance for the team was against the brand-new Los Angeles Dodgers in the ’59 World Series. But in 2005, everything went right — eliminating the Los Angeles of Anaheim in the ALCS and a sweep of then NL-champion Houston in the World Series, erasing an 88-year title lapse. Things were now fixed. In a good way. Enough so that President Barack Obama could wear a black “Sox” cap and feel die-hard redemption in the eyes of Ozzie Guillen, Mark Buehrle, Paul Konerko and Jermaine Dye.

= “The Whiz Kids: How the 1950 Phillies Took the Pennant, Lost the World Series and Changed Philadelphia Baseball Forever,” by Dennis Snelling, University of Nebraska Press, 328 pages, $36.95, to be released in June.

The latest retelling about a team that went 91-63-3 to win the NL by a game over the Brooklyn Dodgers in a thrilling 10 inning game on the last day of the season, was swept by the Yankees in the World Series and had most of its stars under the age of 30 is this time authored by Snelling, a SABR scribe who was not part of the group of contributors and editors who pulled together “The Whiz Kids Take the Pennant: The 1950 Philadelphia Phillies,” by SABR in 2018. We’ll bank on Snelling, who did “The Greatest Minor League: A History of the Pacific Coast League, 1903-1957,” back in 2012 for McFarland.

= “The Boys of ’62 Inspiring Story of the San Pedro Little League Champs,” by Tim Urisch, Pedro Scribes Publishing, 252 pages, $16.95; released in December, 2024.

A lot of “The Wonder Years” tied up in this by one of the team’s members decades later from a team that played in the Western Boys Baseball Association (WBBA) World Series. A review of the book at well from San Pedro Today as well as more when the team was included in the LA SportsWalk in San Pedro.

1 thought on “Day 2 of 2025 baseball book reviews: Dutiful data + time-tested teamwork = victory over murky mythology”