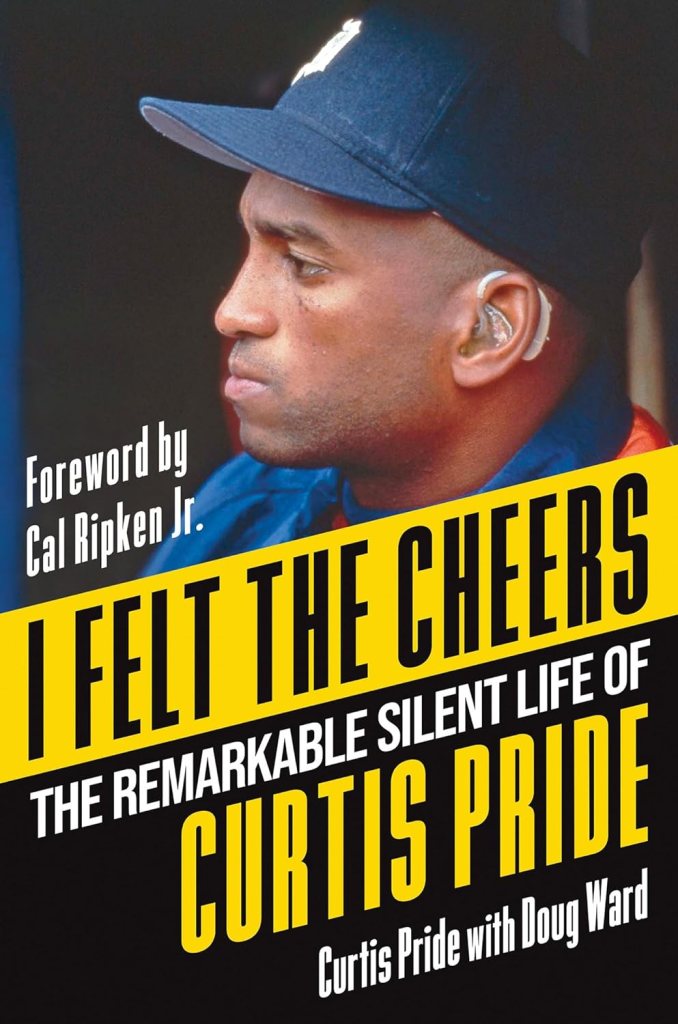

“I Felt the Cheers:

The Remarkable Silent Life of

Curtis Pride”

The author: Curtis Pride, with Doug Ward

The details: Kensington, $29, 240 pages, released February 25, 2025; best available at the publishers website and Bookshop.org.

A review in 90 feet or less

The idea, as well as the fact, that Curtis Pride is still proudly identified these days as an MLB Ambassador for Inclusion since 2015 is worth mentioning right out of the batters’ box.

The announcement came in an MLB press release that remains on its website. The same proclamation noted that Billy Bean, hired as the first Ambassador for Inclusion a year earlier, was to be promoted to VP of Social Responsibility and Inclusion.

To be clear: Bean was actually named Senior VP of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion. Even if the press release now reads otherwise. At least Bean kept his title in tact when MLB.com did an obituary on him in August of 2024. Maybe that title dies with him.

In his new autobiography, waiting until almost near the end, Pride acknowledges the responsibilities he feels have come with that designation for the league’s DEI program.

“We worked together to find ways to be more inclusive, which can mean greater accessibility in every stadium, or finding ways for teams to build bridges with their local community,” Pride wrote on page 198. “We did programs for children with disabilities. In my travels I met everyone: the stadium director, the community relations director, marketing officials and attorneys. Basically I worked with a team’s different departments to cover as many different bases as possible.

“One day I believe those club executives will be made up of more minorities and people with disabilities. It was work I really enjoyed, probably because I believe it is so important. It’s a long process, but we are moving in the right direction. The goal is to make Major League Baseball the most inclusive and accessible of all the major sports.”

Pride puts his humility on the line here. It comes from birth.

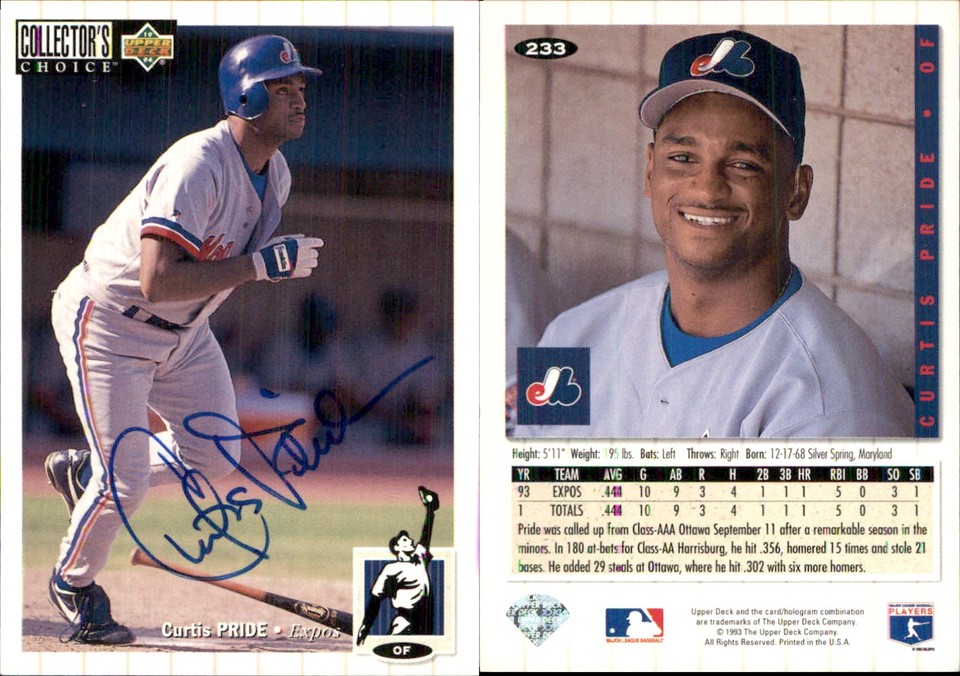

In an 11-year MLB career spent with six teams, and concluding with the Angels from 2004 to 2006, he also at one point he was signed by the Dodgers as a free agent in July of 2000, but released at the end of the season without ever coming up.

“I am a man of faith, and Pride is one of the seven deadly sins, but I never really cared for that definition. I prefer Webster’s: ‘The quality or state of being proud.’ That was me. I was nothing if not proud—proud of my name, my family, and the circumstances I had to overcome.”

His career WAR: 1.0, as an outfielder, DH and pinch-hitter.

Read beyond the back of the baseball card.

Pride wasn’t the first, and likely won’t be the last, to reach the MLB level after overcoming this particular setback.

Those with hearing loss who’ve played MLB started with Ed “Dummy” Dundon, a pitcher/first baseman with the American Association’s Columbus Buckeyes (1883 to ’84). The most famous deaf player in MLB history was Billy “Dummy” Hoy, whose 14 seasons covering the late 19th Century and two more years in 1901 and ’02 until he was 40 included leading the NL in stolen bases with 82 as a 26-year-old rookie with the Washington Nationals.

You don’t think Pride wasn’t called “Dummy” himself? Worse.

Coaching at Gallaudet University in his hometown of Washington D.C., a private institution for the education of the deaf and hard of hearing since 1864, Prides’ Division III Bisons baseball team plays its games at Hoy Field.

Pride says Hoy was “an enormous source of inspiration for me,” not just the Deaf community’s Jackie Robinson, but “as its Babe Ruth, Ted Williams, Mickey Mantle and any other transformative star you can name.”

At that time, “there was nothing derogatory about the nickname, but rather it was a literal description of his most prominent feature, like calling someone with a slight build ‘Slim’ … it wasn’t clever, but it wasn’t offensive either.

“I have been called ‘Dummy’ on more than one occasion and when it happens, it comes with malice. Stupid, idiot, numbskull, retard, spaz and the ever-popular Helen Keller all have been used to address me. And when it happens, I take great offense. But I don’t show it. To react to those taunts would mean losing control.”

Pride seems to have learned from Jackie Robinson, as he says he didn’t experience “anything close” to what Robinson did, but “I have so much appreciation for him because I got a small taste of discrimination and ignorance. … I was determined to let my game show people what I was all about. That was the way to honor Dummy Hoy and deaf people everywhere.”

Pride shares that perhaps his most memorable experiences on an MLB field was when the Angels and general manager Bill Stoneman picked him up in late in 2004, almost 10 years after Stoneman got him onto the Montreal Expos’ roster.

On Sept. 29, Angels manager Mike Scioscia sent Pride in to play left field in the seventh inning when Garret Anderson was injured. With two outs in the ninth, as the Angels trailed Texas 6-5 and could see their AL West pursuit slipping away, Pride launched a ball off Rangers All-Star closer Francisco Cordero that hit off the center-field field fence and was recorded as a triple as the throw to the plate didn’t get Vlad Guerrero, who scored from first and tied the game at 6-6. The Angels won that 158th game of the season in extra innings on a Troy Glaus homer, and ended up winning the AL West.

“I think about that at bat from time to time, not because it’s one my greatest glories — which is surely is — but rather to remind myself of the greatest things that can happen when you maintain faith and keep plugging along. …Anything is possible if you keep trying.”

In addition to experiencing 95-percent deafness at birth because of rubella, Pride also has overcome tachycardia arrhythmia — a fluctuating heart beat. He shows more his humility as well with chapters in the book dedicated to his parents. His father, John Lewis Pride, highlighted in the afterward, died in September of 2024 but was able to read the manuscript during the editing process.

Pride addresses more about the stigma his parents helped him overcome in seeing how they encouraged him to play only baseball but basketball and soccer at William & Mary University: “People have a perception of deafness as something that affects your intelligence. It does not, of course. … My parents knew a degree from one of the best schools in the nation would be a quick and effective defense against anyone who doubted my intelligence … there is a not a day that goes by that I don’t appreciate their foresight. They knew education was important and my deafness only served to up the ante.”

Whether it is Pride’s work with the MLB DEI issues, or continuing to coach the game on the college level, the last two lines of his story are the most poignant on page 206:

“No, hearing isn’t a big deal.

“The important thing is being heard.”

How it goes in the scorebook

Hear here.

Maybe get yourself the audio book version of this and add another layer of profound wonder to this story.

The publishers, having labeled this as “Biography & Autobiography/People With Disabilities,” also frame it as something to be included amidst the “powerful anthem of ability diversity and overcoming the odds.” They use as examples: Nyle DiMarco’s “Deaf Utopia,” Jim Abbott’s “Imperfect: An Improbable Life,” Des Linden’s “Choosing To Run” and Mallory Weggemann’s “Limitless: The Power of Hope and Resilience to Overcome Circumstance.”

Pride has done himself well to be in that company. Congrats as well to Doug Ward, the Southern California co-author and UCLA grad who worked in the Angels’ publications department for nine years (overlapping with Pride).

Abbott pitched without a right hand, coming up with the Angels’ system and having a 10-year MLB career that included throwing a perfect game with the Yankees. Perfect, of course, if you believe in such things.

Jim Eisenreich played 15 MLB seasons, the last with the Dodgers, as he battled Tourette Syndrome.

Rick Rhoden’s 16-year MLB career included his first five with the Dodgers, an All Star in 1976, injured his right knee at age 8 and an infection developed into osteomyelitis that almost led to amputation. He compensated for having a left leg that was longer than his right by winning 151 games, then went to a career as a professional golfer.

Pete Gray played without most of his right arm. Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown had two partially missing fingers on his pitching hand and lasted 15 seasons. Tarik-El-Abour is the first pro player to be diagnosed with Autism. David Freese, hero of the 2011 World Series for St. Louis, is one of many who battled mental depression.

We acknowledge the profound accomplishment of all those feats.

So while July 26 is National Disability Independence Day, commemorating the signing of the ADA into law in 1990, and Dec. 3 is International Day of Persons With Disabilities, you can calendar any other spot as Curtis Pride Day after reading this.

We’re willing to file this book in a category Pride can be proud of and leave it at that.

You can look it up: More to ponder

== Ron Kaplan zooms in on Pride and author Doug Ward for this interview.

== In Curtis Pride’s SABR bio project, it notes:

“Why Pride didn’t get more opportunities at the highest level – and why he jumped from organization to organization – is somewhat of a mystery. Asked if his deafness played a role, Pride wouldn’t speculate as to whether he was discriminated against. All he’d say was, ‘Teams appreciated my ability on the field, and more importantly, I was a very good team player.’ A former teammate concurred, adding that effort was never a problem – he took pride in every aspect of the game, from hitting to fielding to base-running.”

That bio appears in “Overcoming Adversity: The Tony Conigliaro Award” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Clayton Trutor.

= Pride discusses his book in an MLB.com interview linked here.

= Jeff Moeller reviews the book for The Sporting Tribune.com

1 thought on “Day 5 of 2025 baseball book reviews: Pride and prejudices”