“Jim Gilliam: The Forgotten Dodger”

The author: Steve Dittmore

The details: August Publications, 340 pages, $24.95, released Feb. 4, 2025; best available at the publishers website, the author’s website and Bookshop.org.

***

“They Changed the Game: 50 Stories

and Illustrations Celebrating Creativity in Sports”

The authors: Matthew and Ariana Broerman

The details: Triumph Books, 112 pages, $23.95, released Feb. 25, 2025; best available at the publisher’s website, the official book website, InkAndCraft.com or Bookshop.org.

***

“Dream Merchant of the Perfect Game:

The Life and Legacy of Frank ‘Doc’ Sykes“

The author: Bernard McKenna

The details: Mascot Books/Amplify Publishing, 340 pages, $17.95, released April 1, 2025; best available at the publishers website or Bookshop.org.

***

“Play Harder: The Triumph of

Black Baseball in America”

The author: Gerald Early

The details: Ten Speed Press/Penguin Random House, 320 pages, $35, to be released April 29, 2025; best available at the publishers website, the Baseball Hall of Fame and Bookshop.org

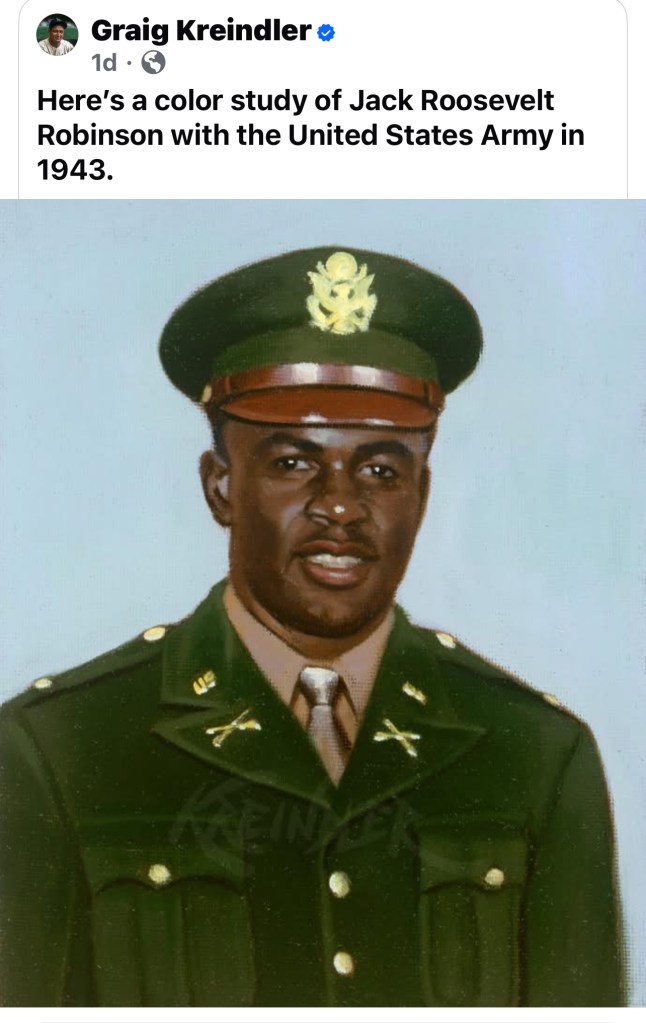

A Jack Robinson preamble

’twas a crafty suggestion til ’twasn’t.

Blasted into the universe prior to the Los Angeles Dodgers’ problematic visit to the White House on April 7, the comment came up: What if every player dons a Jackie Robinson No. 42 jersey, make a statement, take the photo ops, be defiant?

Make ’em all squirm and show their true colors.

It, of course, didn’t happen.

Too much of a political pearl clutch for anyone associated with the one-for-all 2024 World Champs, some of whom just wanted to enjoy the moment more than others.

The franchise’s current trustee funders, too many billions in deep with the Guggenheim Monopoly money machinery, can compartmentalize and separate themselves from the fact that this organization once brought Jack Robinson into the cultural spotlight and then was present when Rachel Robinson accept her husband’s posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom honor by President Ronald Reagan on March 26, 1984.

Concerns were voiced beforehand with extremely valid points. Author-with-a-spine and retired urban policy professor Pete Dreier not only posted in the L.A. Times on March 13, and then for The Nation with the headline “Brooklyn Dodger 1, Draft Dodger 0” but he followed it up with a April 7 Q&A for Capital&Main where he flat out said:

“Yes. I’m disappointed that (the ownership group) didn’t have the courage to speak out. Maybe (minority owner) Billie Jean King and (minority owner) Magic (Johnson) will speak out at some point but so far they haven’t.”

(Seems they were busy on April 7 anyway. Hollywood beckoned):

Continue, Mr. Dreier:

“Trump barely got half of the votes in the United States and got very few in the L.A. area, so it would not be that harmful to the careers of Dodger players for them to speak out against the Dodgers going to meet Trump. And it’s very disappointing that none of them have stepped up to the plate, so to speak.

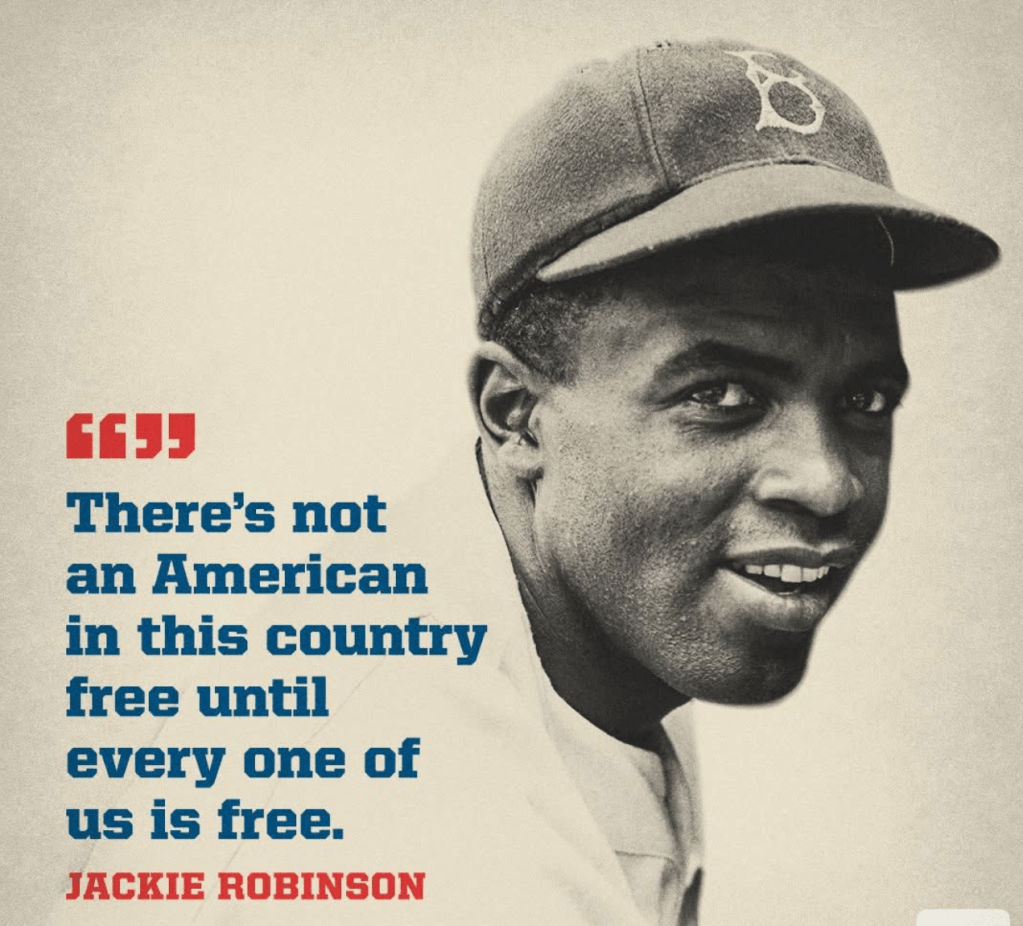

“Jackie Robinson would be outraged by the Dodgers meeting with Trump. Jackie Robinson was a liberal Republican. He went to the Republican convention [in 1964] supporting the liberal Republican Nelson Rockefeller when they nominated Barry Goldwater, and he heard people say things in that convention that so angered him that he came out of that event and he said I know what it must have felt to be at a Nazi rally. Donald Trump is a lot worse.

“Robinson always had the courage of his convictions regardless of what impact it had on him. He was criticized during his playing career for speaking out, and he said I’m always going to speak out against injustice and if you don’t like it, it’s too bad.

“So I’m 100 percent sure Jackie Robinson would be upset that the Dodgers are going to the White House, and I think he’d be extremely disappointed in Mookie Betts in particular.”

None of this will keep them up at night. Especially since a Change.org petition only got about 2,000 complaints — all worth reading if the Dodgers really cared about such things.

A March 30 column by Los Angeles Times writer Dylan Hernandez exposed Dodgers president Stan Kasten talking circles about it was the players who decided to do this, and the organization wasn’t in the position to stop it. Except, it was. It has stepped in many times before in other matters. Maybe if someone else was part of the decision-making process from a previous Dodgers administration, things would have been different.

Now, on April 15, the all-No. 42 roster conversion takes place officially when players, managers, coaches and maybe even licensed interpreters on all 30 teams are required to wear the number for the MLB’s well-interventioned Robinson day of recognition, a day on the calendar since 2004.

What if just the Dodgers, instead of No. 42, wore No. 404 on the back. And “Page Not Found” across the shoulders.

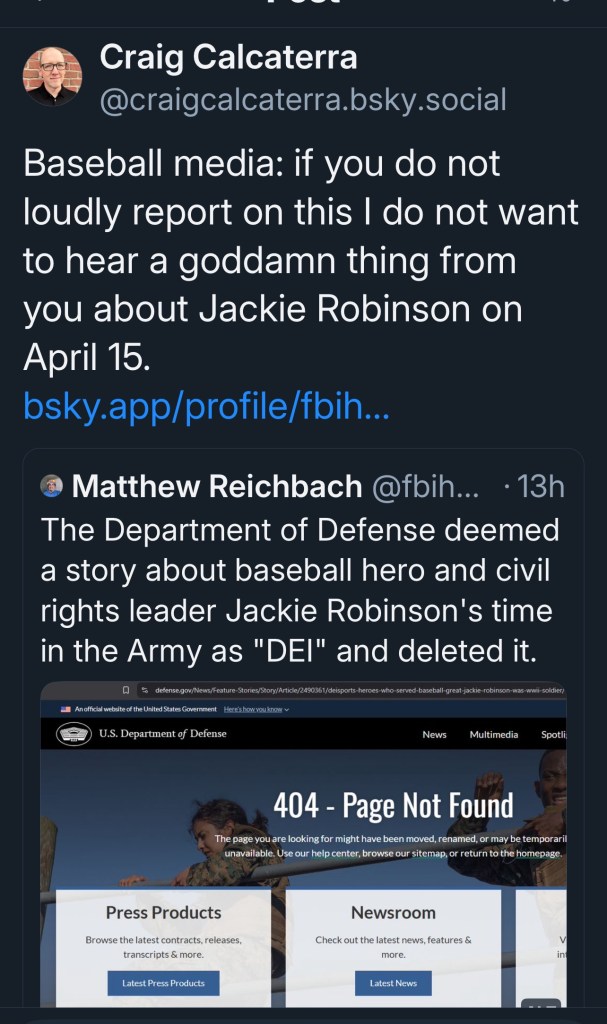

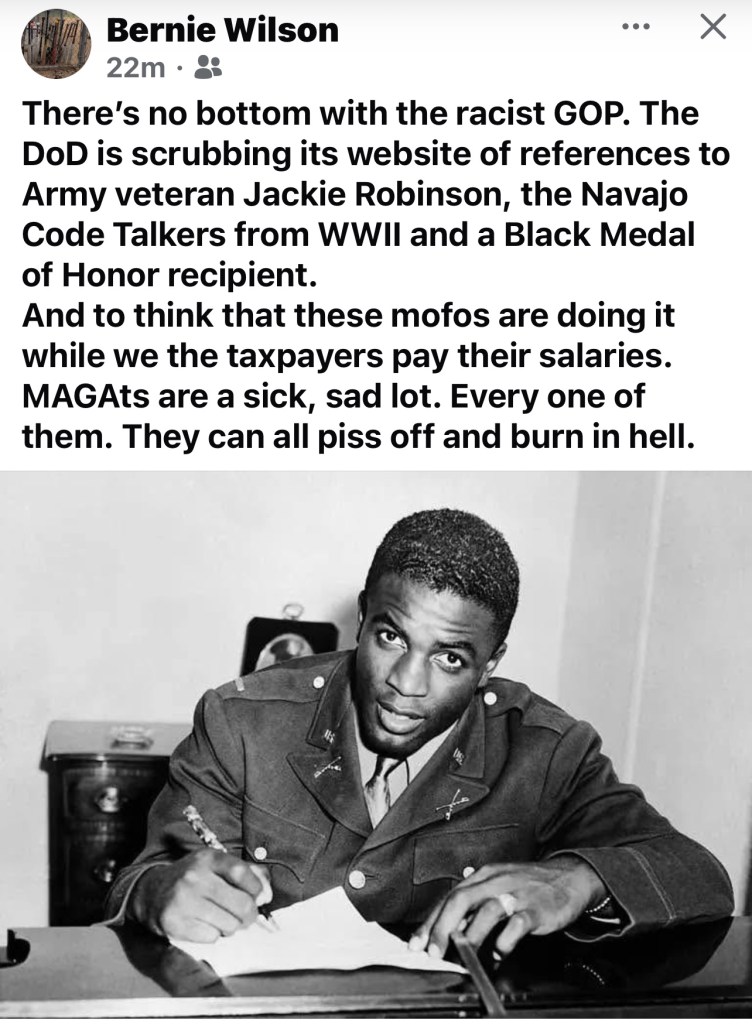

Honor what happened on March 18, when the U.S. Department of Defense’s website scrubbed a story posted titled “Baseball Great Jackie Robinson Was WWII Soldier” as part of its “Sports Heroes Who Served” series. When the URL link was clicked, the “404” code appeared.

Wishy-washy white washing. Cancellation by deletion. Modern day book burning? From those who say they’re just carrying out the commander-in-chief’s orders — the same who would likely not be able to distinguish a library from storage locker.

A fierce blow back to this farce was loud and clear. Anything remotely related to promoting DEI — diversity, equity and inclusion — as per executive orders upset the wrong nest of hornets. It had already happened to stories about the Navajo Code Talkers, the Tuskegee airmen, Marines at Iwo Jima and a bio on Medal of Honor winner Major General Charles Calvin Rodgers, who was Black. All were 404’d.

“Shame on them,” said Darryl Strawberry, the former Crenshaw High and Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder, about those trying to erase the legacy of Robinson and others.

The Robinson piece, created in 2021, was straightforward about his time at UCLA, his military service and his integration of Major League Baseball, his life active in civil rights. It also included an account of a court martial charge related to a dispute with an ornery bus driver who ordered him to move. That was all overturned, leading to an honorable discharge, and where he started into his professional athletic career.

In a dismissive response to the deleted Robinson story, then-Defense Department Press Secretary John Ulyutt doubled down about how DEI is “Discriminatory Equity Ideology” and “a form of woke cultural Marxism that Divides the force, Erodes unit cohesion and Interferes with the services’ core warfighting mission.” (See what he did there with the letters D, E and I? What a marksman).

“In the rare cases that content is removed – either deliberately or by mistake – that is out of the clearly outlined scope of the directive, we instruct the components and they correct the content accordingly.”

In the rare case someone takes ownership for a mistake, this bass-ackward mea culpa didn’t fly even after the post was clumsily restored a day later. There was also reason to believe that a book about Robinson was to be taken out of the U.S. Naval Academy Library as per orders.

We wish we could have heard from Rachel Robinson, who, at 102, is still with us. Robinson’s son, David, 72, on the board of the Jackie Robinson Foundation, said in a statement: “We take great pride in Jackie Robinson’s service to our country as a soldier and a sports hero, an icon whose courage, talent, strength of character and dedication contributed greatly to leveling the playing field not only in professional sports but throughout society. He, of course, is an American hero.”

Negro Leagues Baseball Museum president Bob Kendrick was talking to a writer about the DEI whitewashing issues just a week before that Robinson deletion happened. Kendrick said the story of Robinson is “one of the greatest examples of why diversity in the workplace works. … It seems as though there’s this agenda to stoke fear. Fear of people who don’t necessarily look like each other.”

Scott Ostler of the San Francisco Chronicle wrote: “We know the current President admires Robinson, because he said so recently at a Black History Month press conference, and the current President never lies. ‘Jackie Robinson, what a great athlete that was,’ the current President said. Apparently, one of Robinson’s pronouns is ‘that.’ And all the Jackie Robinson pioneer business, that’s all woke hokum. … The big overall historical purge and cultural cleansing continues … Here’s a number I’d like to see retired: 47.”

On Comedy Central’s “The Daily Show,” mentioning the story included a clip of an ABC report that explained how a “senior military official tells us tonight that the Pentagon relies on computer software to scrub DEI content from its websites and ultimately those stories about Jackie Robinson were removed by mistake.” Host Jordan Klapper added: “Hey don’t blame us. Blame our racist software. We should have never used ChatKKK.”

Social media has preserved a comedy bit by Shane Gillis that may speak to truth more about how Robinson’s debut in 1947 was “the exact moment when white people stopped being cool. … Jackie knocked that (cool) voice out of all the whites.”

Robinson knocked out the baseball world, of course, with his actions. He did it then, and the effects are still felt nearly 80 years later.

Or, are they?

The idea and ideology of DEI, whether it is believed to be or not, is a merit-based mindset. Robinson, for so many years going back to his UCLA football days, merited attention — even if he didn’t get his MLB opportunity until he was 28 years old. That was after three years in the military service (age 23-25).

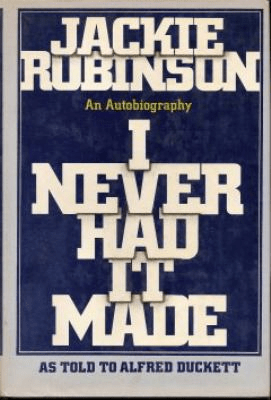

In Robinson’s autobiography “I Never Had It Made,” he tells the story about being in New York’s Harlem area to visit the Apollo Theater for an afternoon show with friends.

“On my way into the lobby, an officer, a plainclothesman, accosted me. He asked me roughly where I was going, and I asked what the hell business it was of his. He grabbed me and spectators passing by told me later that he had pulled out his gun. I was so angry at his grabbing me and so busy telling him he’d better get his hands off me that I didn’t remember seeing the gun. By this time people had started crowding around, excitedly telling him my name, and he backed off.

“Thinking over that incident, it horrifies me to realize what might have happened if I had been just another citizen of Harlem. It shouldn’t be necessary to be named Jackie Robinson to keep from getting brutalized.”

Mind you, this event happened in 1971, nine years after he was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame, and a year before he died.

His cause of death may have been a heart attack on top of diabetes, though some scholars wonder if it wasn’t more attributed to the years of living with racism.

If this Jack Robinson Day 2025 (again, is it something he would have really wanted?) is another moment in time to make sure his voice and wishes and goals still matter, it isn’t lost on us that MLB.com still believes he matters with a fabulous array of Robinson-related merch ready to push out the doors.

The Dodgers’ tickets for the April 15 home game vs. Colorado range from $40 to more than $500 a seat with a “free” Robinson No. 42 jersey (sponsored by his college alma mater).

You can’t put a price on personal freedom and liberty (or maybe they would as well).

Mark Timmons at LADodgerTalk.com pointed out last month that the Dodgers are one of just a few MLB teams that actually aren’t afraid to use DEI as a mantra.DEI is not just a link on their website, but it’s on their main menu. No other MLB team does that.

Writer Craig Calcaterra pointed out the MLB has scrubbed the word “diversity” from what was once its “Diversity and Inclusion” web link. It likely happened in December of 2024. Calcaterra also wrote that when the MLB begins “its annual fetishization/cooption of Jackie Robinson’s legacy as a means of centering itself in Civil Rights history and whitewashing its segregationist past,” just remember how it has “remained silent as the Trump regime attempted to erase Jackie Robinson from history.

“In the meantime, the Trump regime remains a shitty, segregationist enterprise that is unworthy of anyone’s respect or obeisance and Major League Baseball utterly lacks a spine.”

The Athletic, citing Calcaterra’s report, also asked the MLB for a response to that diversity scrub and a spokesperson said: “We are in the process of evaluating our programs for any modifications to eligibility criteria that are needed to ensure our programs are compliant with federal law as they continue forward.”

On April 15, 2025, Calcaterra posted:

Yesterday I received a 1,200+ word press release from Major League Baseball setting forth all of the things it’s doing in honor of the anniversary of Jackie Robinson’s debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. You can read that here.

Not surprisingly, nowhere does it mention that Rob Manfred ordered the elimination of Major League Baseball’s Diversity Pipeline Program and scrubbed MLB’s website of references to diversity, equity, and inclusion because he believes that currying favor with our racist president and his fascist administration is more important than racial equality or improving the very entity which he oversees.

As you see all the players wearing number 42 today, as you watch the commemorative videos and tributes, and as you hear the announcers and various media talking heads speaking about Jackie Robinson, do not forget, for one moment, that Major League Baseball is run by cowards who do not give a single shit about Jackie Robinson’s example or his legacy beyond how they can use it to make themselves look good. They’ll say they do, but it’s all eyewash. Every bit of it. What they have done defines them.

On April 16, Calcaterra circled back:

Chris Towers of CBS got that same press release and he noticed something: nowhere did Major League Baseball explain why Jackie Robinson was significant. It merely says that Robinson “played his first Major League game on April 15, 1947.” The words “integrate/integration,” “segregate/segregated,” “Black,” “African-American” or “color”/”color barrier” are wholly absent and there is no mention of the Negro Leagues whatsoever.

This, as Towers noted, contrasts with last year’s press release which contained a sentence referring to Robinson “spearheading initiatives that support communities and meaningfully address diversity and inclusion at all levels of our sport.” That was removed from the 2025 release.

To sum up: Major League Baseball has eliminated its much-lauded diversity hiring program, it has scrubbed its website of references to racial equality, and now it is refusing to say out loud why Jackie Robinson is significant while still trying to co-opt his legacy. I suppose there could be more deeply cynical shit than that but at the moment I’m having a very hard time imagining what it would be.

The Times’ Hernandez followed up with an April 15 column admonishing the Dodgers again:

Rather than continue to stimulate important conversations, the Dodgers are back to whistling past America’s graveyard, pretending there is nothing hypocritical about visiting President Trump one week and celebrating Jackie Robinson Day the next. The opportunity for the Dodgers to regain their stature as agents of change has come and gone, their salute to Robinson on Tuesday reverting to its previous form as a cynical exercise in stealing the valor of a previous generation.

Walter and Kasten had the power to restart a necessary dialogue at a time when the Trump administration not only sent a brown-skinned man without a criminal record to a Salvadoran prison by mistake but also defied a Supreme Court order to facilitate his return. They didn’t. Their silence was a betrayal, both to the Dodgers and their history.

The only person in a Dodgers uniform who spoke up with something substantial to say on April 15 is another former UCLA player who turned to basketball.

“Trump wants to get rid of DEI,” Kareem Abdul-Jabbar said at the Dodgers’ celebration of Robinson that brought members of the Dodgers and Colorado Rockies out to the Robinson statue in the center-field concourse. “And I think it’s just a ruse to discriminate. So I’m glad that we do things like this, to let everybody in the country know what’s important. They also tried to get rid of Harriet Tubman. But that didn’t work. There was just uproar about that. But you have to take that into consideration when we think about what’s going on today.”

Dodgers manager Dave Roberts was left to clean up the mess. Again.

“I don’t personally view it as talking out of both sides of our mouth,” Roberts said Tuesday. “I understand how people feel that way. But I do think that supporting our country, staying unified, aligned, is what I believe in personally. I just believe in doing things the right way and I think people are going to have their opinions on what we did last week, but I do know that we all stand unified and we all have different stories and backgrounds and economic, political beliefs. But I was proud that we all stood together.”

Roberts spent nearly all of his 12-minute pregame session with members of the media discussing Robinson, DEI and his own status as one of two Black managers in the major leagues.

“I think he would say we need to do better,” Roberts said.

The MLB position for Senior VP for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion may go unfilled since former Dodger outfielder Billy Bean, who once held that spot, died last year. The MLB’s Diversity Pipeline Program, which has seen more than 400 assisted hires, has been quiet since October 2023, when America First Legal, the conservative non-profit group led by Trump ally Stephen Miller, filed a federal civil rights complaint with the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission against MLB for racially discriminatory programs. One of the four programs referenced in the complaint was the MLB’s Diversity Pipeline Program.

Michael Weintreb, a San Francisco-based screenwriter who opines about sports, history, culture and politics on his Substack account, recently wrote in light of the DOD DEI cleansing exercise:

“There are moments now — too many of them to be honest — when the sheer surreality of what we’re living through sets in. I am not merely speaking of the crushing venality (or) colossal incompetence; I am speaking of the realization that everything this country has built toward and fought for since the Civil War is now being completely twisted and stepped on by a cabal of scoundrels and bigots. … I never really thought I would live through a truly Orwellian moment, but then the news broke that Elon Musk’s team of post-adolescent AI code-bros had (accidentally, but not really) scrubbed an article about Jackie Robinson and his service in the Army, and I realized once again just how deeply fucked this all is.

“Even if you think DEI has its excesses, how is it humanly possible to sweep Jackie Robinson into some imaginary bucket of ‘DEI hires’ unless you are engaging in unapologetic bigotry? … It is utterly infuriating that we have to apparently fight these battles all over again.

“History tell us that such sacrifice for the greater good — the sacrifice Jackie Robinson was willing to make to change America — is how progress eventually occurs. And this is why Robinson’s story will endure, and this is why these execrable people will not.”

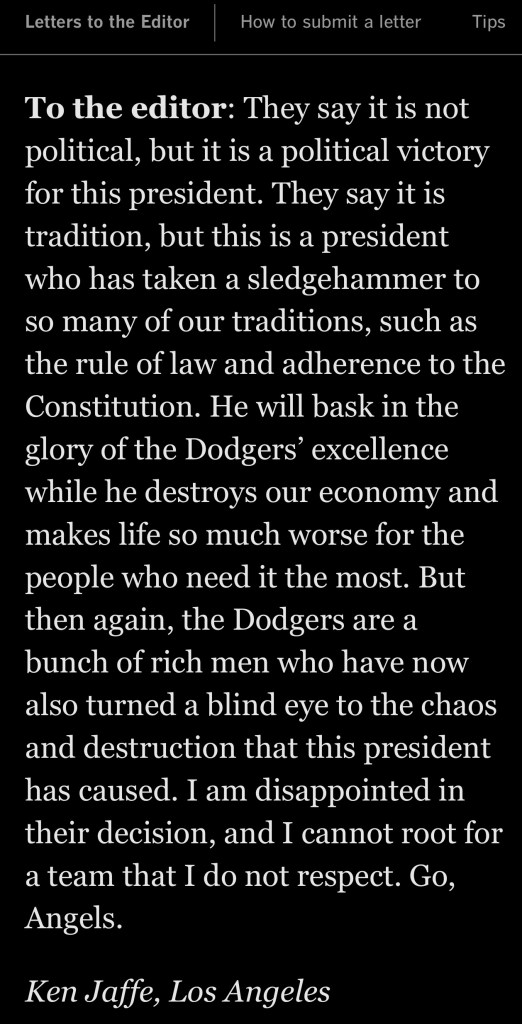

Letters’ to the editors? Sure, we found some timely ones to the L.A. Times:

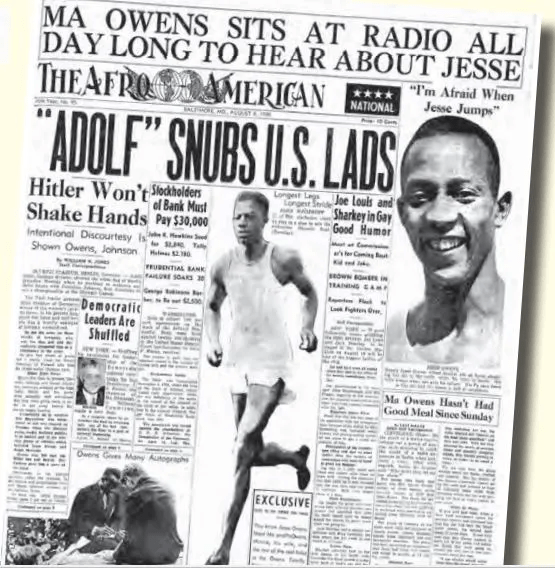

What side of history will you be on? “I cheered on the Dodgers on, because this was sports, not politics” won’t cut it. Jesse Owens wouldn’t allow himself to be photographed with, let alone exploited, by Adolph Hitler in the 1936 Olympics (and if you pull one up on X, it’s a hoax).

At the end of the day, if the combination platter of the letters DEI trigger something in people, like “affirmative action” or “social justice” or “universal healthcare,” twisting the idea into a compromised and distorted concept from its original intent, let’s find a different way, a better, way to phrase it for the common good.

Somehow work Jack Roosevelt Robinson’s initials into it.

Justice.

Rectitude.

Resilience.

Book reviews in 90 feet or less

The newest manuscripts that connect and correlate well with the subject matter of Robinson:

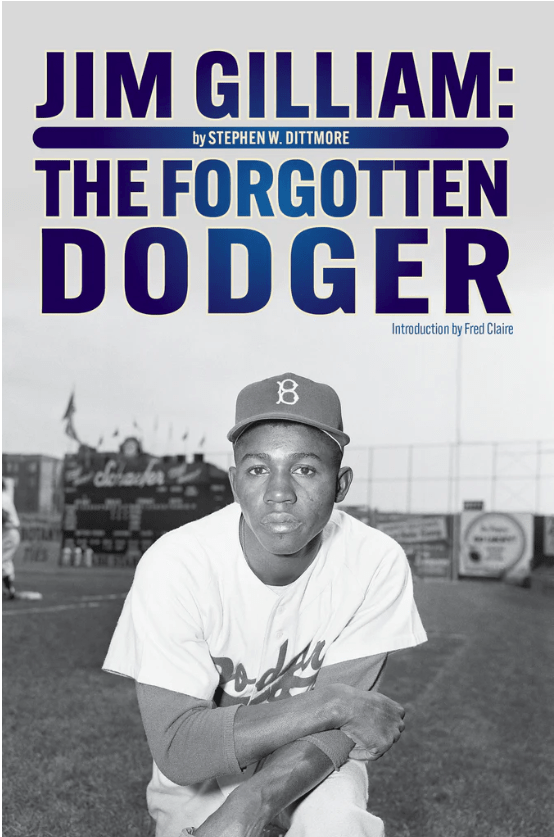

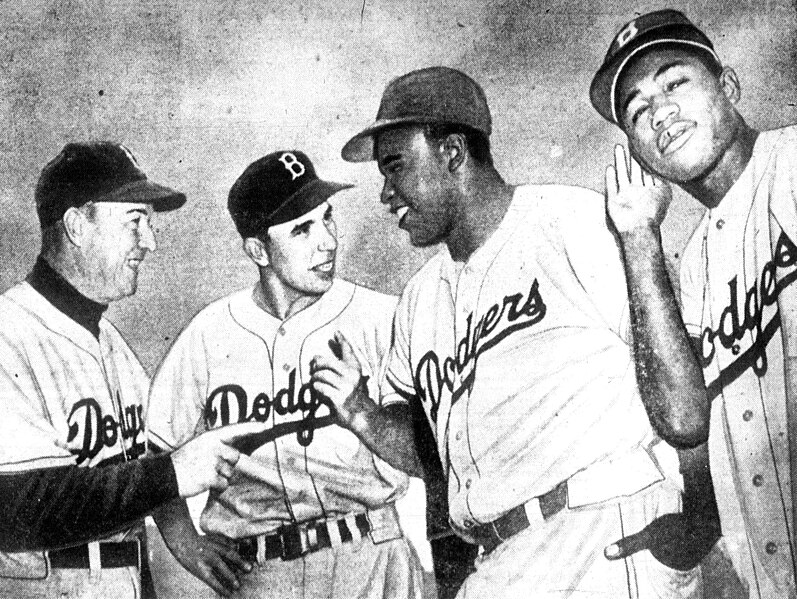

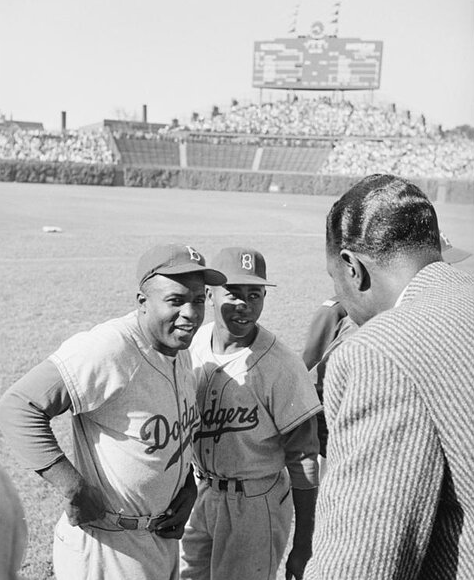

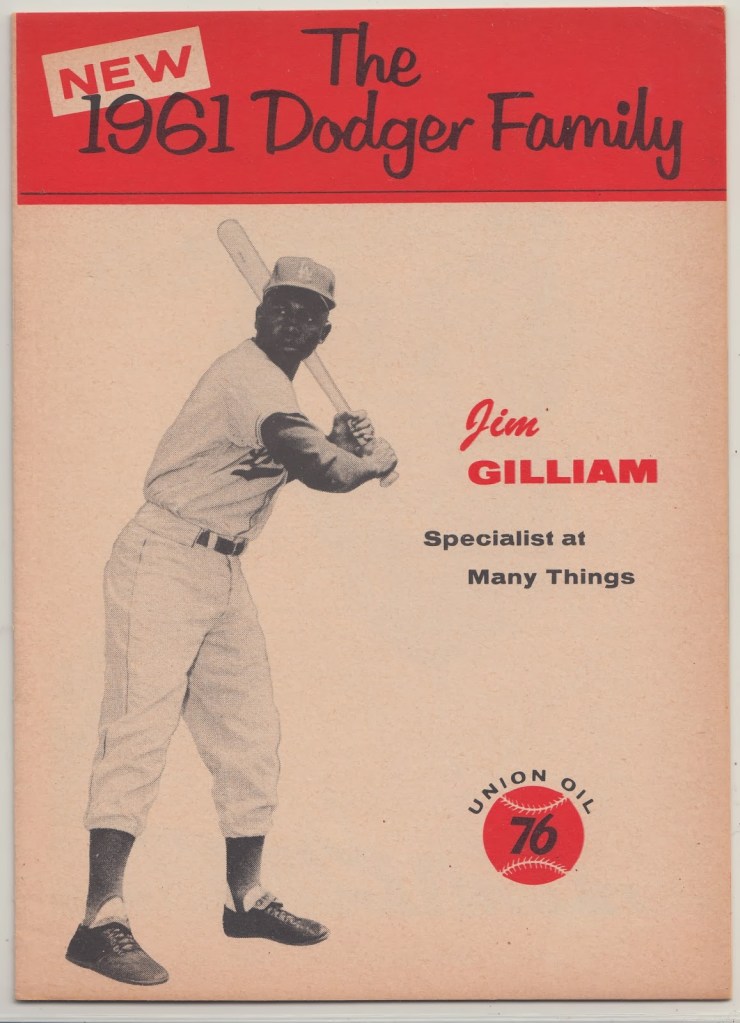

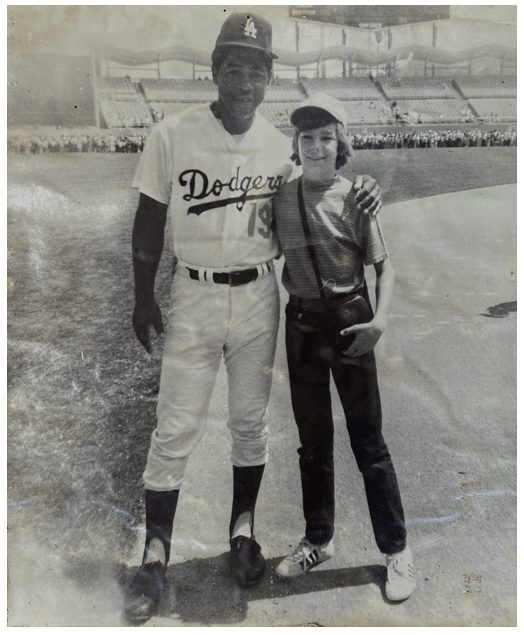

Without Jackie Robinson’s signing to play for the Brooklyn Dodgers’ Triple-A Montreal in 1946 as an entry point to the major leagues in ’47, 17-year-old Jim Gilliam, then trying to make it onto the Negro League’s Baltimore Elite Giants, wouldn’t be inclined to believe he had any sort of pathway to what his life became.

Ponder all the lessons learned when the two became Dodgers’ teammates.

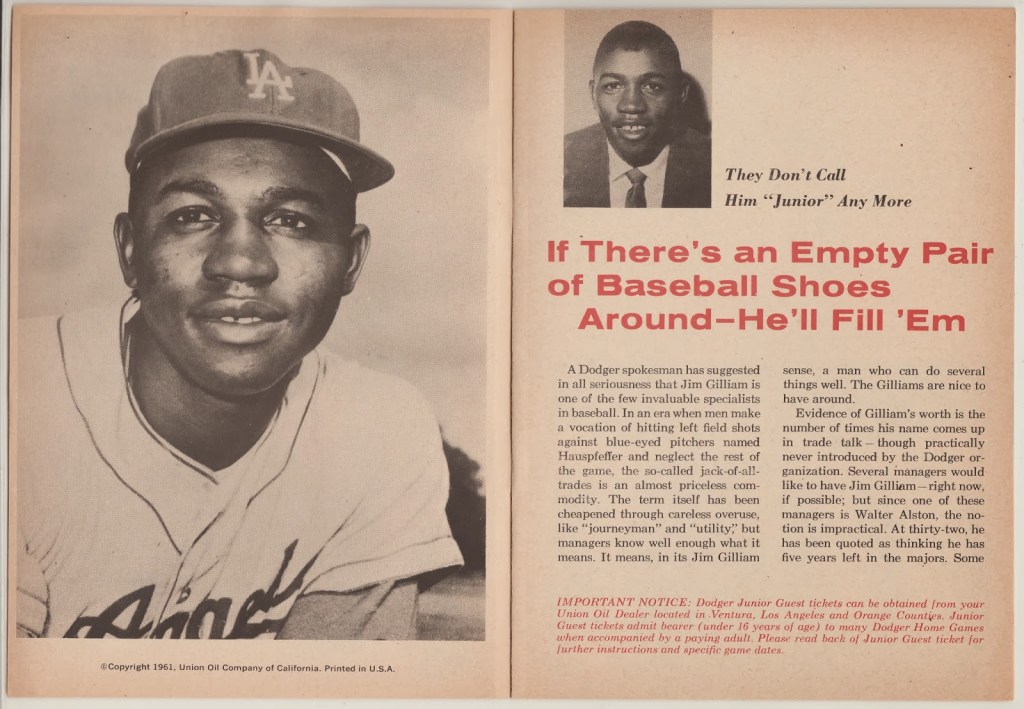

Despite the title chosen for Steve Dittmore’s first-class biographical project — and it is not an uncommon adjective assigned here — Gilliam has never been forgotten with many of us in Southern California.

More likely, he’s just never been fully understood and appreciated. He rarely called attention to himself.

The Devil is in Dittmore’s details.

Which is why this project merits attention for all it has achieved with research, organization and humanization.

With his No. 19 among the Dodgers’ retired since 1978 — the first to have been done so without having an official Baseball Hall of Fame plaque — the gravity of that gesture by the O’Malley family organization was clearly understood by the players and the fans as Gilliam died suddenly less than two weeks before his 49th birthday, on the eve of another Dodgers-Yankees World Series (where Dodgers players wore a black “19” circle patch. A giant red “19” stands among the retired numbers at the top level of the ballpark as well. Go ahead, touch it.

His 14 years as a player bridging Brooklyn to Los Angeles, twice coming out of retirement in the 1960s to become a key part of a World Series title chase at the end, and another full decade as the first Black assigned to be on the coaching lines was remarkably comforting to see. It was like seeing Robinson’s legacy as an action item.

There’s the easy-to-spot Jim Gilliam Park & Rec Center near La Brea and Stocker in L.A. in the Baldwin Hills area with a great view of the city.

It was also consoling on a recent trip to Nashville, coming upon a street sign marked Junior Gilliam Way and the No. 19 as the official address for the ballpark of the Milwaukee Brewers’ Triple-A Sounds — perhaps the home of a MLB team in the future.

The sounds of silence we’ve had trying to get our heads around that title — forgotten? — doesn’t have to be a sticking point as much as it can be boring our way to a different but similarly appropriate entry point.

On why Dittmore, a Dodgers fan native to Southern California (born in Redondo Beach, grew up in Torrance and Westlake Village, moved to Minneapolis in ’76 when his father changed jobs), wanted to pursue this subject. He writes he did it with “no idea where the narrative would go, with whom I would interact, or, for that matter, how I would accomplish this. Perhaps that is why this published book is both satisfying and amazing now that it is complete. … That so many strangers would do this for me speaks to the universal regard with which people remember Jim Gilliam.”

Respect and defend the Gilliam brand is a noble effort in times when he could be seen as not a real part of the “Boys of Summer” and other narratives presented during that time period of the game’s Civil Rights advancements. Adding Fred Claire (see Facebook post above on the Robinson DEI fiasco) is another stamp of credibility.

Dittmore comes from a place of higher-education administration and sports shaping, including a journalism foundation at Drake University and a PhD from Louisville. A SABR member since 2023, Dittmore’s “Glory Days” Substack newsletter that covers his areas of interest and expertise on top of “Springsteen and whatever else” is also a fine explanation about where he’s coming at this from.

Muse away.

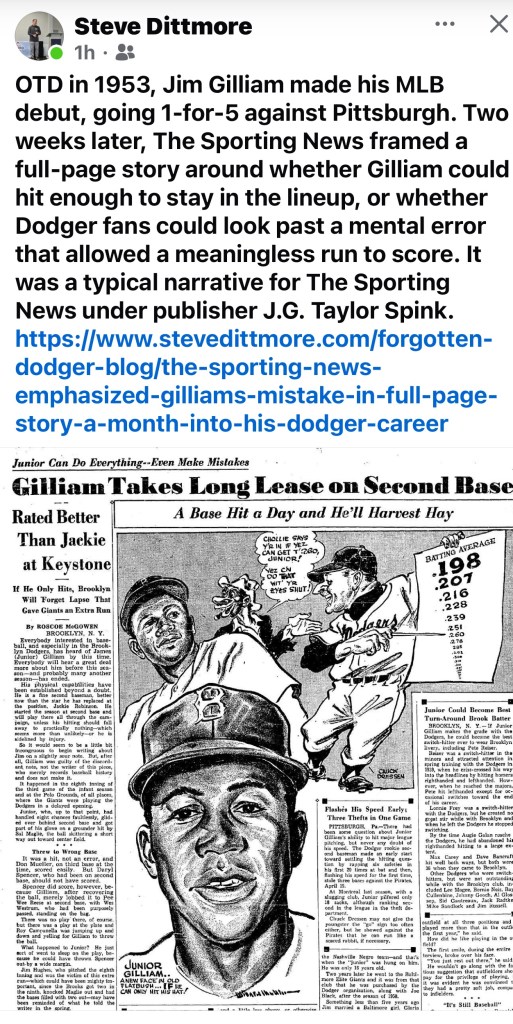

Gilliam’s most glorious days seemed to be, at first, dancing in the dark about how he’s be perceived as Robinson’s down-the-road replacement, which seems almost preposterous to laying that on him. The comparisons were well before Gilliam became the 1953 NL Rookie of the Year some seven seasons after Robinson received the first rookie aware in ’47 (when it was just for one player in both leagues; Gilliam was the latest in a string of Black players who were now honored with it).

Although their careers overlapped just five season — ’53 to ’57 — all in Brooklyn, Gilliam was a Robinson game-changer.

By the time the 1955 Dodgers won their first World Series, Gilliam was the key man at the keystone sack. Robinson, at age 36, had been moved to third, next to shortstop Pee Wee Reese, himself 37. Gilliam would end up playing in seven World Series, winning four, including three in Los Angeles, a place where Robinson may have made his mark as an athlete at UCLA but would never play professionally and never have a home again.

By the numbers, looking at the Dodgers’ franchise’s all-time leaders, it can be bewildering to process how Gilliam’s 40.7 WAR is eighth best. His 1,889 hits are eighth (although he has 2,021 total based on three years with the Baltimore Elite Giants of the Negro League from 1946 to ’48). His 1,036 walks are second. His 1,956 games played is fifth, and his 8,322 plate appearances is third. His 1,163 runs scored is fourth.

So many listed below him on these lists have Hall of Fame career resumes.

While there may be 19 new and interesting facts learned about Gilliam in every chapter — amazing for a player who seems to have been nearly traded every year to make room for someone else but ends up center stage at the critical moments — our focus here on the relationship he had to have with Robinson is even more intriguing for us.

Especially considering that without Robinson, Gilliam’s MLB entry point may have been further delayed and not as impactful.

Dittmore’s Chapter 7 called “Moving Jackie” gets to the heart of it all.

Robinson and his wife Rachel took trip to Puerto Rico in February 1953, “as much as a scouting mission as it was a vacation.” Gilliam was a Caribbean Series All Star, and would be coming to the Dodgers’ Vero Beach camp in Florida that March ready to “knock on baseball’s Second Gate.”

As Dittmore has crafted to help create a structure for Gilliam’s career, he sets up three passage ways — gates — that need to be opened, designed in the first place “to limit the role of Blacks in organized baseball.” The first was Robinson’s 1947 debut. The second would be the sport’s “unspoken quota on the number of Black players on a given basis.” The third was becoming the first Black base coach, and considered as a prime candidate to be the first Black manager before another Robinson, Frank, did it in 1975. Gilliam helped open that fourth gate.

Today, Dittmore is a more and more the gatekeeper of Gilliam’s legacy, beyond why he belongs in the Dodgers’ Ring of Honor and has become the anchor branding in so many influential landmarks around the city.

We need more of this. Such as:

= A couple of Dittmore presentation about the Gilliam project, including a TrueBlueLA.com podcast appearance:

= An excerpt of Chapter 12 from Dittmore’s book via Howard Cole’s Substack platform.

= A Society for American Baseball Research game history piece by Howard Rosenberg about the Dodgers’ June 14, 1957 win, in their last season in Brooklyn, as Gilliam’s steal of home stops pitchers’ duel and gifts Don Newcombe birthday win. Add to that Gilliam’s SABR bio project piece by Jeff Angus.

= Gilliam is memorialized by a B. H. Fairchild poem, which includes a link to Vin Scully’s video testimonial in 2015 at Nashville’s renaming of the road in front of First Tennessee Park.

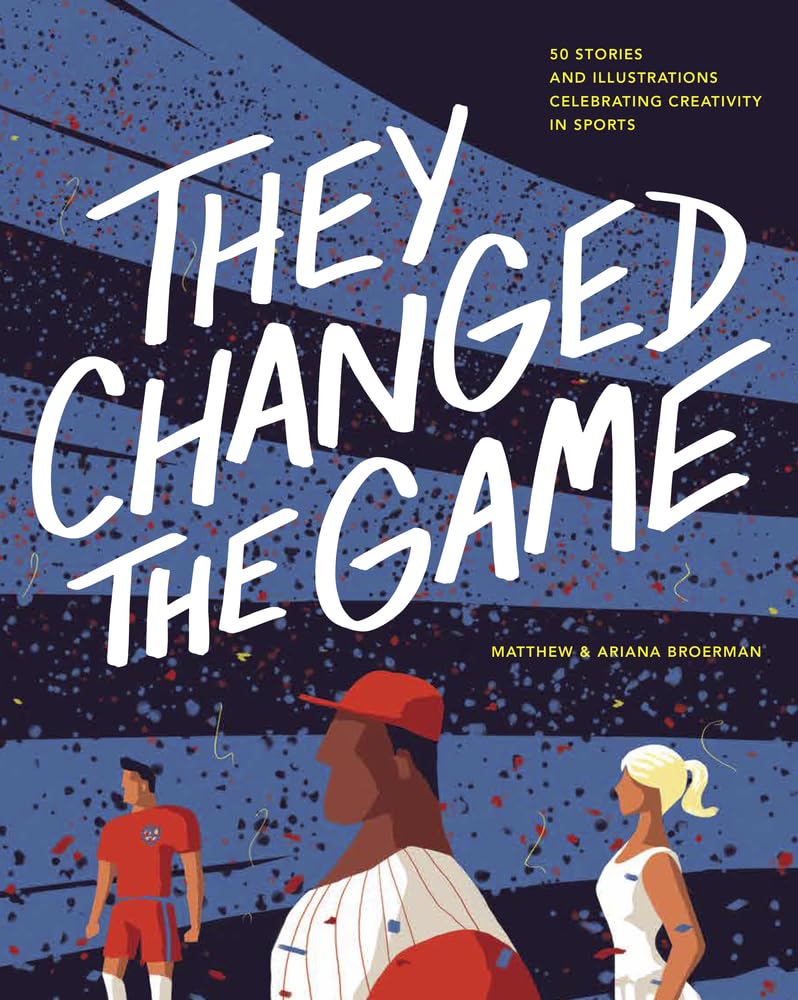

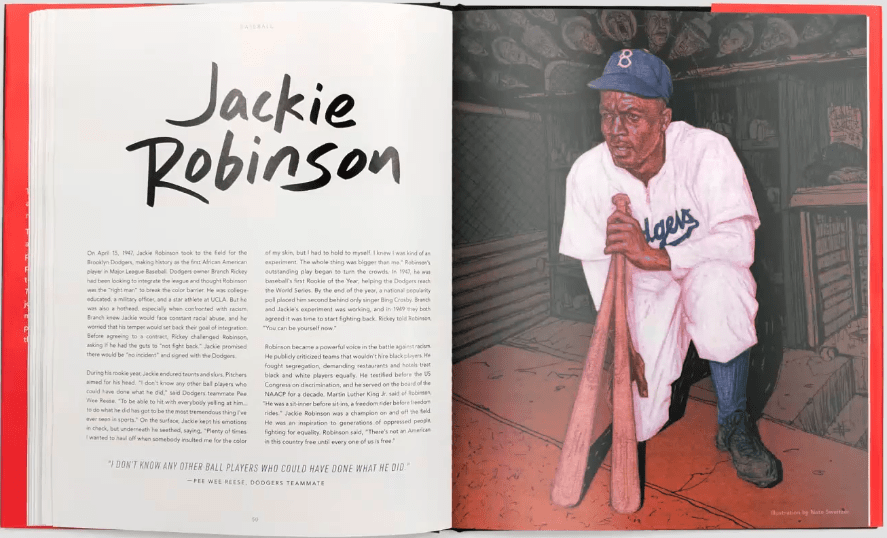

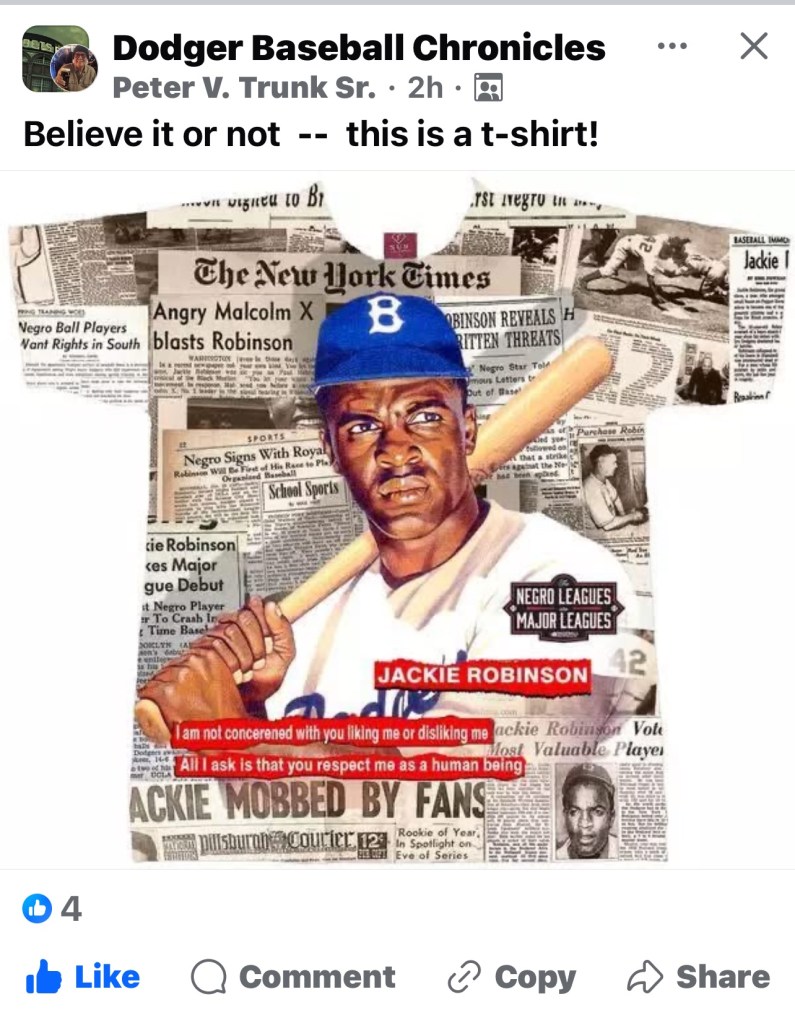

In “They Changed the Game,” Matthew and Ariana Broerman didn’t really have to include Robinson as one of their 50 subjects with this project that seems intended for young adults, but is most delightful for the older population.

But because they did, it puts Robinson in a much larger orbit of those who accomplished things in life that happened to be sports related. Babe Ruth, Bob Gibson, Doug Allison, Candy Cummings, Curt Flood, Ed Walsh and Tommy John are part of the baseball eclectic bunch as well as Robinson — each for their own trailblazing moments. But also are Ludwig Guttman of the Paralympic Games, John Devitt of swimming, Tom Blake of surfing, Axel Paulsen of figure skating, Dick Fosbury of high jumping fame, and Robert Walter Johnson of tennis.

The art tells the story as much as the words, to both feel and absorb the subject. Although it is nice to see the Martin Luther King quote here: “He was a sit-inner before the sit-ins, a freedom rider before the Freedom Rides.”

Just a two-page spread, but a classy tribute that Robinson deserves to be included in, but also isn’t something that should be taken for granted.

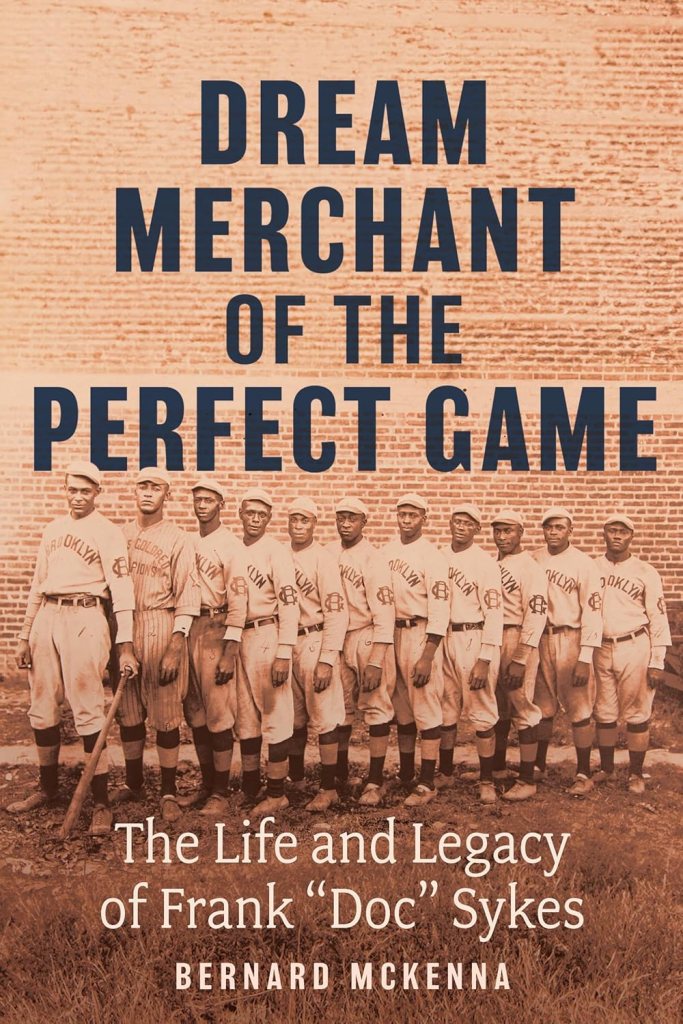

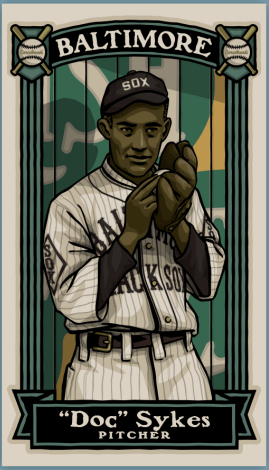

In “Dream Merchant,” most of us are finally introduced to the Decatur, Alabama, native who attended Howard University and Atlanta Baptist College (now Morehouse) and got a degree in dentistry. Oh, and he played baseball.

First, in various Negro Leagues from 1913 to 1922, minus for two years in the U.S. Army during World War I. He pitched (relying on a spitball) for two seasons with what is now considered the major leagues — the Baltimore Black Sox of the Eastern Colored League in ’23 and ’24, aged 31 and 32.

Sykes’ long-lasting impact in society came in 1933 when he agreed, despite death threats and hate mail, to testify in a highly publicized retrial of the Scottsboro Boys case — nine Black men accused of raping two white women on a train. Eight were tried and sentenced to death within weeks of their arrest, but the bias was so obvious, Albert Einstein and Thomas Mann signed off on a telegram experssing outrage to the governor of Alabama. It became a landmark Supreme Court case early in the Civil Rights movement about judicial diversity and not excluding Blacks based on the color of their skin from the jury pool.

Which Hall of Fames does Sykes belong in? Several, perhaps.

McKenna writes he first knew of Sykes’ story when doing research for “The Baltimore Black Sox: A Negro League History 1913-1936” for McFarland and was approached by Skyes’ son, Charles, decided to try to get his dad’s story done more completely. As McKenna writes: “I grew to be astonished simultaneously at both how little I knew and how his courage and determination shaped history. The more I learned about the man, the more I understood the necessity of a biography. … Men like Doc Sykes, whose most productive years came before the formation of the Negro Leagues, contributed to the way African American professional baseball developed independently of the white game. The way Jackie Robinson played ball, which revolutionized the game after his debut in 1947, was born in the decades of the twentieth century, laying the foundation for the style of Negro League baseball that Jackie learned.”

And above: Another beautiful recap of Sykes life (and a great looking illustration card) as created by Gary Cieradkowski.

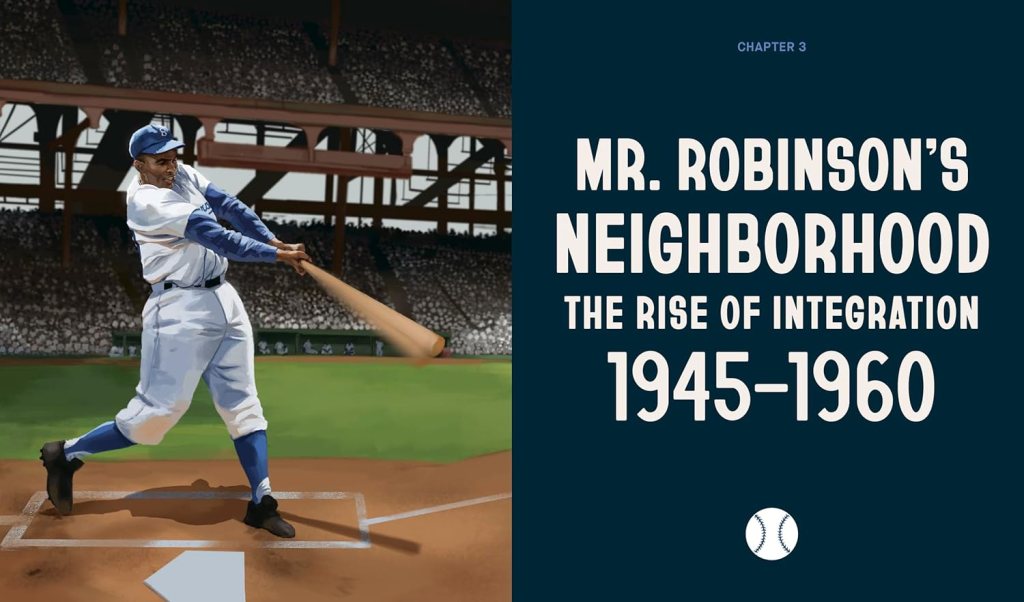

The release of “Play Harder” puts Early as the-facto narrator as he has already been collaborating with the Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum to create more cultural history.

Early, who got some great face and voice time in Ken Burns’ “Baseball” documentary in 1994, the same year he won the National Book Critics Circle Award for criticism with “The Culture of Bruising: Essays on Prizefighting, Literature and Modern American Culture,” which followed up on his 1989 “Tuxedo Junction: Essays on American Culture.”

Always a great read by those who follow him on GoodReads.com, with one of our favorites being the 1998 “Body Language: Writers on Sport,” Early is now at Washington University in St. Louis, where he is editor of the online journal, The Common Reader while teaching English as well as African and African-American Studies.

In spanning the way the game has been shaped by its influential Black players — from Moses Fleetwood Walker to Ken Griffey Jr. — the book will be released soon and the publishers have requested no reviews post before that. So, we’ll wait. But not for long.

Until then, here’s a presentation Early did a year ago discussing his work with the Hall of Fame and its then-new exhibit on Black Baseball that opened in May of ’24. This book is meant to accompany the exhibit.

How they go in the scorebook

While it can sometimes seem as if 42 new books come out about Robinson each year, this time it feels particularly important that any and all be required reading and re-reading, from early readers to YA to historical recreations.

Many are willing to keep the flame lit and hold those accountable to the heat.

Mitch Nathanson did this piece for the Philadelphia Inquirer that pointed out: If you look at the rosters of some clubs when it comes to Black players, it almost feels like it’s still April 14, 1947, the last day of the segregated big leagues.

“Dodgers fans, who pride themselves on rooting for the franchise that had the guts to sign and promote Robinson nearly eight decades earlier, only counted one Black starter in their lineup that day: the club’s leadoff hitter — superstar shortstop Mookie Betts. …

“We haven’t come as far as we like to think we have. And if we’d strip away the pomp and ornamentation that cushions and protects us from some uncomfortable truths, that would become all too clear.”

Whether Robinson would endorse this April 15 event or not, JR25 arrival gives us a righteous moment to make sure his legacy isn’t in peril. We can’t be distracted by those baited-and-switchers who continue to attempt to yell things dismissively into existence.

Robinson’s action spoke louder than his critics. These books carry on that promise.

You can look it up: More to ponder

Also currently (or soon) in circulation:

= “Opening the Door for Jackie: The Untold Story of Baseball’s Integration,” by Keith Evan Crook, McFarland Books, 236 pages, $39.95, due in August, 2025; best available the publisher’s website and Bookshop.org

To mark the 80th anniversary of when Branch Rickey, who became the team’s president and GM in 1943 and part owner in ‘44, finally signed to Robinson in ’47, it seems all we need to do is watch the movie “42” again. This research project by Crook tries to reframe the narrative and provide more context as the rest of the world spun around this event — such as how the NAACP membership grew from 18,000 to 520,000 between the 1941 Pearl Harbor attack and the ’45 signing of Robinson, which launched more awareness of employment discrimination. Crook, who has a masters in history from Harvard, lives in Stamford, Conn., a city where Robinson lived with his family from the mid-1950s until his death in 1973 at age 53, facing all sorts of housing discrimination in the process.

“Brooklyn Dodgers Transactions, 1890–1957 — A History and Analysis,” by Lyle Spatz, McFarland Books, 266 pages, $39.95, released Jan. 5, 2025; best found at the publisher’s website and Bookshop.org:

Spatz, once chair of the SABR Baseball Records Committee for 25 years, does a record excavation of what might otherwise look like a perfunctory list of trading, drafting, buying and selling off players but makes a case for re-visiting them to extract new perspectives, see who got the best value compared to how it looked at the time it was executed. Also deals made one season with the intent to fill an immediate position need might skew the process of a subsequent deal that now seems rather obvious. Player availability during war times also influenced deals, and it influence from league officials also came into play.

For our exercise here, and as Robinson is one of those highlighted on the cover, here’s what is written about starting on page 192:

October 23, 1945: Signed free agent shortstop Jackie Robinson

A “bold move, opposed almost unanimously by the other clubs, but Rickey went ahead.” Spatz finds a quote from Rickey’s son, Branch Jr., about the transaction that will send Robinson to the International League’s Montreal Royals, owned by Hector Racine: “Mr. Racine and my father will undoubtedly be severly criticized in some sections of the country where racial prejudice is rampant, but they won’t avoid it if it comes. Robinson is a fine type of young man, intelligent and college bred. … Some players with us now may even quit, but they’ll be back in baseball after they work a year or two in a cotton mill. … Negros fought alongside white and shared the foxhole dangers and they should get a fair trail in baseball.”

The domino effect: Catcher Roy Campanella and pitcher Don Newcombe are signed in April, 1946 and sent to Class B Nashua in New Hampshire. Pitcher Dan Bankhead is signed in August, ’47 from the Memphis Red Sox of the Negro American League before he became the MLB’s first Black pitcher two days later, hitting a home run in his first at-bat. Meanwhile, first basemen Howie Schultz was sold to Philadelphia in May, 1947, and Ed Stevens to Pittsburgh in November, ’47 because Robinson needed a position as second base taken by Eddie Stanky. A March ’48 trade of Stanky to the Boston Braves for first baseman Ray Sanders was “to allow Jackie Robinson to move from first base to second base” even if manager Leo Durocher, returning as manager after a suspension, said 21-year-old Eddie Miksis “is my second baseman.”

A December ’47 trade of outfielder Dixie Walker to Pittsburgh (with the Dodgers getting pitcher Preacher Row and shortstop Billy Cox) is also covered and “many people jumped to the conclusion that Rickey was trading Walker because of his early opposition to Jackie Robinson. That false perception exists to this day. True, Walker had asked for a trade during spring training but he later changed his mind, as Rickey knew.” Walker was the Dodgers’ leader in batting average and RBI in ’47 but just turned 37.

“A Baseball Book of Days: Thirty-One Moments that Transformed the Game,” by Phil Coffin, McFarland, 254 pages, $29.95, released Feb. 20, 2025; best available at the publisher’s website and Bookshop.org:

Chapter 8’s date of destiny is called “Jackie Robinson Opens The Door. Quietly.” Robinson was as one of 29 rookies who saw action on the first day of the season, and Coffin writes: “It was a big deal — the first African American player in a Major League game since the 1880s — but if you weren’t paying close attention, you might not have known it.” The Brooklyn Eagle had two photos of Robinson with its game story, but Robinson wasn’t mentioned until the ninth paragraph. The New York Times made a reference to Robinson’s sacrifice bunt in the sixth paragraph of its story, while the newspapers’ esteemed columnist, Arthur Daley, was more focused on the fate of suspended Dodgers manager Leo Durocher. “The muscular Negro minds his own business and shrewdly makes no effort to push himself,” Daley eventually wrote. “He speaks quietly and intelligently when spoken to and already has made a strong impression.”

= “Race and Resistence in Boston: A Contested Sports History,” edited by Robert Cvornyek and Douglas Stark, University of Nebraska Press, 404 pages, $39.95, released February 1, 2025; best available the the publisher’s website and Bookshop.org

From the index:

Robinson, Jackie: Boston Red Sox and,

as integrationist hero,

integration of,

popularity of,

return of,

tryout of,

Willie O’Ree and

Robinson’s famously unproductive tryout with the Red Sox in April 1945, with Sam Jethro and Marvin Williams, was said to be arranged by sportswriters Sam Lacy of the Baltimore Afro-America and Wendell Smith of the Pittsburgh Courier. It says here, white reporter Dave Egan of the Boston Daily Record was “also supportive,” as was local politician/city councilor Izzy Muchnick, “a strong believer in integration.” But like a 1942 exhibition game at Fenway Park between the Baltimore Elite Giants and Philadelphia Stars — the first time Negro League teams played there — it “turned out to be just more symbolism. … Nothing came of it.” Mabray Kountze was a key Black community activist and journalist, and was “bitterly disappointed and irritated that the players were not shown more respect: Robinson had been in the army fighting for his country, yet when he entered Fenway Park, “many saw him as just another Colored boy,” Kountze recalled. The Boston Braves had their first Black player, Jethro, in 1950. The Red Sox were the last Major League team to integrate nearly 15 years after that tryout. And Kountze kept pushing his equality mantra through the city.

And last but not least:

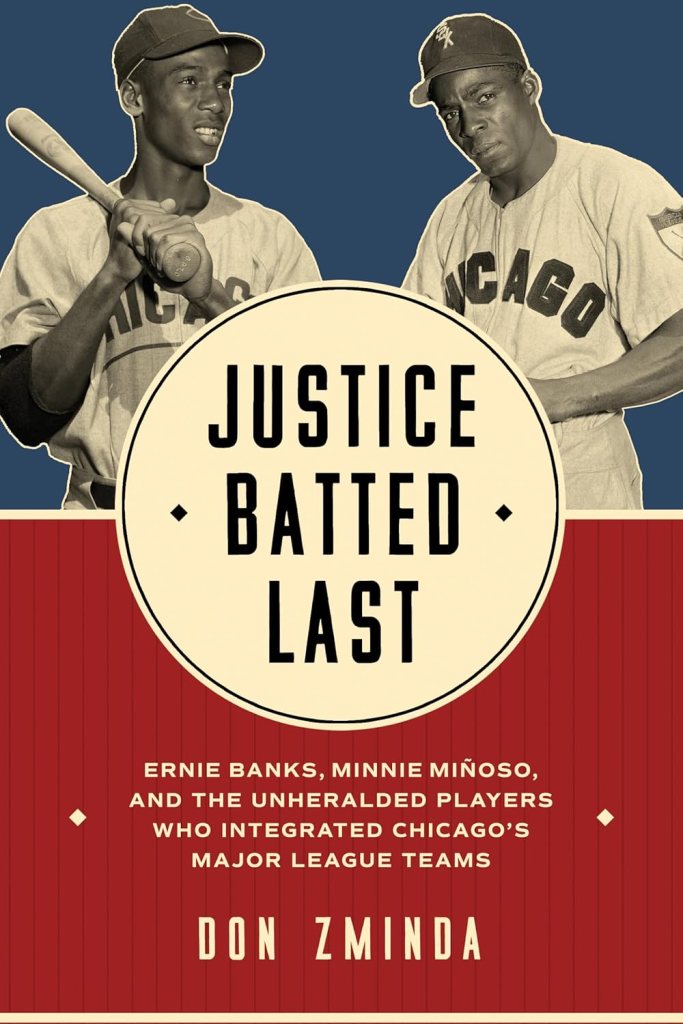

= “Justice Batted Last: Ernie Banks, Minnie Miñoso, and the Unheralded Players Who Integrated Chicago’s Major League Teams,” by Don Zminda, University of Illinois Press; 3 Fields Books, 278 pages, $22.95, released March 11, 2025; best found on the publisher’s website and Bookshop.org.

The Windy City’s breaking-barriers entry point was a few years after Robinson, and they, too, had two future Hall of Famers. Minnie Minoso was there for the White Sox on May 1, 1951 — he was originally signed by Cleveland in 1948 but White Sox GM Frank Lane got him in a trade because, by that point, it was said “the Indians were too integrated.” It came upon the backdrop of a 1951 race riot in suburban Cicero, where a white mob abetted by local police attacked a building that had rented to Black tenants. Ernie Banks became the Cubs’ first Black player in 1953 — barely. Four years earlier, the franchise though they had their first Black player with San Francisco-based catcher Charles Pope, who started at their low-level minor-league affiliate in Visalia, hit .286, was released and never hit the big leagues. They also had outfielder Gene Baker, who had languished in the minors for four seasons and, after Banks played his first game September 17, ’53, Baker came up three days later, recovering from an injury. L.A.-based Zminda has entertained us in the past with a bio of Harry Caray in 2019 and a look back at the 1919 Black Sox Scandal that expanded into more storylines in 2021.

A postscript:

And another post script:

== Media researcher David Schwartz recently uncovered a clip of Jack Robinson talking golf with Tommy Armour:

1 thought on “Day 8 of 2025 baseball book reviews: An illogical ERA in the WAR on DEI”