“Skipper: Why Baseball Managers

Matter and Always Will”

Updated: 6.25.25

The author: Scott Miller

The details: Grand Central Publishing/Hatchette Book Group, $30, 400 pages, released May 13, 2025; best available at the publishers website and Bookshop.org.

“The Last Manager:

How Earl Weaver Tricked, Tormented

& Reinvented Baseball”

The author: John W. Miller

The details: Avid Reader Press/Simon & Schuster; $30, 368 pages, released March 4, 2025; best available at the publishers website and Bookshop.org.

A review in 90 feet or less

Joe Maddon had a burr in his saddle. The former Angels’ skipper felt tossed overboard with a flimsy life preserver that, for the moment, provided him with nothing to preserve much of his patience or self-worth.

As once the manager of the successful Tampa Bay Rays when the organization was at the forefront of the analytics revolution in the 2000s, Maddon rode the Chicago Cubs to 103 wins and the 2016 World Series title, despite arm-wrestling the front office over lineup decision and then exposing himself at various times in the championship series against Cleveland.

Maddon’s return to the Los Angeles Angels starting in 2000 (he had interim managerial stints in 1996 and ’99) was once again too short to properly size up. It should have been a victory lap after all the years he spent as a team’s bench coach and fact-checker of managerial decisions on the fly. Instead it was more internal combustion of old school-new school thinking — at least that’s one way of thinking about it.

Jason Jenks from The Athletic reached out to Maddon recently for a Q&A that started this way:

You sent me something you wrote in which you said that your definition of leadership has changed. How?

In the past, I always received direction from whoever was in charge, but then I was permitted to go out and do the job as I perceived was the right way to do it. I’ll give you an example. When I first started as a bench coach in the mid-90s, there was no pamphlet on how to be a bench coach. I didn’t get any direction. The assumption was that I was there to advise the manager on a daily basis, primarily during the course of the game. Before games, I would put together scouting reports and breakdowns. I didn’t get any real direction on that either.

My point is, when I started doing that, nobody told me what to do. At all. I built all these programs because I felt, if I was a manager, this is what I would want. I was empowered to be the bench coach. I felt free to do my job. I never felt controlled. I felt the exact opposite.

So what’s changed?

As a coach, I’m not out there creating my own methods. I’m following the methods that are being given to me, primarily through data and information. Which is good. Because when it comes to data today, it’s not just me scouting the other team. Data today combines every play, every pitch, so of course it’s going to be accurate. But the point is, all of that stuff is taken from upstairs (the front office) to downstairs (the coaches). There’s no leeway to make adjustments anymore based on what you see.

When I was with the Angels, Brian Butterfield, my infield coach, would want to make micro-adjustments during a game based on defense, where a hitter might be late on the ball. All of a sudden, the ball is going away from the planned spot. But if he moved the infielders, as an example, after the game he was told: “Just play the dots.” In other words, coaches became neutered because if you attempted to do that, that was considered going rogue. Just follow the dots. Stop thinking. Stop using your experience. Stop using your sense of feel and what you’re seeing. Just follow the dots.

Just to make sure I understand what you’re saying: You think leaders need to give people information, but then empower them to make their own decisions, not restrict them.

Yes.

Let me ask you this: Why does this change bother you?

Because … it doesn’t permit you to react to a situation that you absolutely see as being different. All these numbers are based on large sample sizes, and I understand that. To me, a large sample size is pretty much infallible when it comes down to acquisitions in the offseason. But it is fallible when it comes down to trends in the moment.

So when you’re talking about how to set my defense on August 15, or how to pitch somebody on August 15, I need something more immediate and not just a large sample size. What is he like right now? Has he changed? Has he lost his confidence, or is he more confident than he’s ever been? There are fluctuations with people. That’s my problem: It bothers me that coaches, managers, whoever are not permitted to use their years of experience to make adjustments in the moment based on what they see.

By the time “The Book Of Joe: Trying Not to Suck at Baseball and Life” came out in October of 2022, co-written with Tom Verducci, Maddon’s life with the Angels was unceremoniously over.

A team with Shohei Ohtani and Mike Trout, and a year after their post-COVID lineup also had Albert Pujols and still lost 85 games, had stumbled to a 27-29 start to the season. Frustration reigned.

Today’s world can already feel a bit chaotic, disjointed, counter-intuitive. Supercilious. Even regular cilious.

Just getting through the day for a normal person can be a challenge.

Yet, we manage. How, and why, is worth a discussion.

One coping mechanism is to find a baseball game to watch. Dig in, lean back and second-guess the manager. That’s part of the mental diversion chess match.

The Los Angeles Dodgers second- and third- and fourth-guessed themselves when it came to Dave Roberts. Especially in the winter of those years after the Dodgers were whiskers away from hoisting a title trophy despite a loaded roster of well-paid talent.

Yet, at some point, the organization that in a previous regime once gave one-year deals annually to future Hall of Fame managers Walter Alston and Tommy Lasorda decided this past spring that Roberts, considering the alternatives, was finally worthy of a four-year extension through 2029, $8.1 million a season would make him “one of the highest-paid” to do what he does.

His job, as it turns out, is basically to do his best to coordinate a plan of survive and advance, understand no one is perfect, smile for the cameras, and avoid landmines.

Be patient and hurry. Straddle popular and unpopular. Represent the organization’s belief that he is of value, especially someone of both African American and Japanese descent.

With that deal, they’ve also fast-tracked his first managerial-influenced bobblehead. The one created in his honor goes out at Dodger Stadium on April 26, whether those ticket-buyers like it or not (at least it’s not a bobblehead of the owner — don’t ever think of that option, no matter who owns the team. Unless it’s Magic Johnson or Billie Jean King).

Some may recall back in September of ’23, when there was 21 bobbleheads given out by the Dodgers for all sorts of silly reasons, one of them was of Dave Roberts depicted as a Dodgers’ player sliding into a base headfirst. That was more passive-aggressive amidst the dilly-dally of that season’s trinkets.

The newest one is of him celebrating the 2024 World Series title. Or, at least, celebrating something worthwhile because the trophy isn’t being hoisted (as it has been with others).

All in all, this seems like a perfect cross promotion idea — bring Mattel into this, as the toy company already has a doll named Skipper Roberts, the younger sister of Barbie. Since 1964.

How do Dodgers fans get to this point after all their pointed finger-pointing when it came to Roberts and decisions made in the most recent seasons?

In 2019, Will Leitch wrote for MLB.com: “Could Dave Roberts be the next Grady Little,” amplifying all the questionable decisions he made made in ’17, ’18, and ’19 playoffs, adding up to three near-misses in the championship crapshoot.

Little did Leitch (or the rest of us) know that, five years later, Roberts would not only avoid being toast, but he’d be the toast of L.A.

As late as last September, Roberts knew he could have been shitcanned had the Dodgers not escaped past San Diego in the first round of the playoffs. That was hardly a given as Roberts and the braintrust had to patch together a bullpen game facing a 2-1 deficit. Hoping for the best, and somehow getting it.

“I do think that if we didn’t win that game it would have become very noisy,” Roberts admitted of the NLDS Game 4. “A team that was obviously super-talented to lose three years in a row in the first round – albeit it takes all of us to win and lose – but I do think that calls for my job would have been heightened.”

The 2024 World Series could have blown up as well. Roberts rode Walker Buehler to the final out of Game 5, avoiding the last two back at Dodger Stadium where, again, all it might have taken is the Yankees’ Aaron Judge to wake up and decide the verdict. (At least that’s the takeaway from the latest AppleTV + documentary, “Fight for Glory: 2024 World Series”)

Roberts’ managerial resume, at this point, is, of course, somewhat awesome by a pure data assessment. In the nine seasons prior to 2025, his .627 career regular-season winning percentage (851-506) is the best in MLB history among managers with at least 1,000 games. He has been there for eight NL West titles, four National League pennants and two World Series titles.

As Roberts was ramping up with the Dodgers, Mike Scioscia was on a slow exit from the Disneyland Cars ride from the Los Angeles Angels of Atrocities Against Anaheim. The two overlapped three seasons before the Angels led their all-time winningest manager go after 19 seasons in 2018. We will not likely see a skipper in today’s game have that long a shelf life.

Maddon, along with Brad Ausmus, Phil Nevin and Ron Washington (not in that order) have been subsequently hired to match wits, and paychecks, with Roberts over the last seven seasons.

What’s a manager to do these days? With all the pre-game data gathering and discussion, having their eyes match their hearts interconnected with their judgment levers, any decision can backfire as well as flourish depending on how the players’ react and perform.

A manager today oversees a pitching starting rotation of a half-dozen pretty ponies, many interchangeable by their roles and injuries — a far cry from having to harness four Clydesdales to pull the wagon on a reliable rotation. Constructing a bullpen is all about leverage situations and ever-readiness to enter on a whim. A closer? Try an opener.

Review challenges are now factored in — when do we do it or what do we save for later innings?

Rosters are made up of a collection of generational personalities. Joe Torre discovered as much when he finally exited his spot after three seasons with the Dodgers in 2010, handing it all off to the person he thought he groomed for the spot, Don Mattingly, because Torre felt he just couldn’t communicate well with the current group of players. Mattingly, 20 years younger that Torre, lasted five more seasons in L.A., then seven more in Miami.

Watching us watch baseball watching the managers, it’s about time (according to our watch) we do more reading on the subject.

Scott Miller’s run as a baseball beat writer/columnist/author goes back to the Los Angeles Times’ San Diego and Orange County editions, leading to a career as a national-based scribe and New York Times contributor and co-author of “Ninety Percent Mental,” with former MLB pitcher Bob Tewksbury in 2018, is required to back up his opinion and analysis and explanatory pieces with some evidence of context and resourcefulness. He does.

Miller intelligently starts his book with the creation of the IBM microcomputer in 1977 and what it was all about at that point. And, today, how its become so integrated in the baseball decision making process — from front office down the field, in real time. He ends it with an update on the technology end of things in this 50-year period, and also identifies possible females who could be first-up as a big-league manager based on the way things operate today.

In between, he makes the best case we’ve read to date why, despite what some may believe, humans still manage to make the final call. And that matters. Hence, the book title.

(Which also makes us wonder: The TV sit-com from the ’60s was called “Gilligan’s Island.” Yet, if not for the courage of the fearless Skipper, how would a gaggle of Gilligans survived?)

Miller’s explainer how people like Roberts or Scioscia or Washington aren’t reduced to middle-managers, or are being micro-managed from above based on org charts, but it is far more collaborative. Managers once had all the power. And it could be a lonely existence.

In going in depth chapter by chapter with interviews and discussion about how managers such as Maddon, Aaron Boone, Kevin Cash, Terry Francona, Dusty Baker (and others of color), Bob Melvin and others who navigate the position from previous “autocrats,” the section on Roberts titled “Tangled Up in Dodger Blue” should be must-reading for SoCal baseball followers.

It starts with the fact that last fall, Roberts had to be aware that, in Miller’s words, “a know-nothing, bottom-feeding president of the United States trashed his pitching moves in the middle of a freaking World Series game.”

Miller was embedded with Roberts during a week of games late in 2022 to get an inside look on the decision-making process, as well as have Roberts best explain it. This was at a time when the Dodgers, with Trea Turner, Cody Bellinger and newly acquired Freddie Freeman, Tyler Anderson, Julio Urias and stopper Craig Kimbrel won 111 games yet lost the division series 3-1 to San Diego.

“Roberts is two parts baseball man and one part emcee,” Miller explains. “It’s all part of the job in today’s world. … He interacts with the grace of a symphony orchestra conductor in full performance. … One of the keys to Roberts is his authenticity. … Roberts’ internal thermostat is naturally set to even-tempered and good-natured but he doesn’t flinch when tough conversations are needed.”

Nothing that another doze of ZzzQuil won’t help with when day turns to night turns to another day game.

Roberts admits that players like Yasiel Puig “took a lot of bandwidth” when he replaced Mattingly in the main chair. Roberts also says he still isn’t satisfied for how he handled the personalities or expectations of platoon players like Joc Pederson or Kike Hernandez before they left via free agency — except the fact Hernandez came back to L.A. via trade after two-and-a-half seasons years in Boston shows there’s been learning on both sides. Roberts had that experience himself as a player, believing he had the skills to be in every day and not be marginalized.

And here’s a heads up: Roberts reveals he really thinks he can do this gig for a 10-to-15-year run, “and if I could stay with the Dodgers, that would be ideal,” he said.

This is his 10th year. His current deal goes to 2029. That would be 14 seasons. Alston did 23 seasons and retired. Lasorda did 20 seasons and stepped away with heart issues.

Roberts seems to have learned from them, and can lean into the reality of how the game takes its toll.

If you leave on your own terms, fantastic, but that’s so rare these days. Roberts knows that it’s all so much administrative than it is teaching any more.

“The hardest part is managing my time,” Roberts admits.

Scott Miller ends his prologue in “Skipper” by weaving in the voice of Earl Weaver:

“ ‘A manager’s job is simple,’ Weaver once said. “For 162 games, you try not to screw up all that smart stuff your organization did last December.’

“As usual, Weaver was ahead of his time. If only he knew how ‘simple’ the job would remain in that vein as sea changes soon would sweep across the game.”

John W. Miller goes to page 5 in his first chapter of “The Last Manager” to pull in the voice of the Dave Roberts as an example of those current managers who “professed envy for the power of their predecessors.”

Said Roberts: “Each manager, his ball club, it was his team, and everyone knew that, and now the mindset is it’s our team. With that comes a lot of questions being asked, a lot more collaboration. I don’t think it’s a bad thing, it’s just different.”

There was “never any question that the Orioles were Weaver’s team,” Miller continues.

One of the things we learned from Lee Kluck’s 2024 biography on Harry Dalton, the Angels’ GM from 1972 to 1977 who was lured to Orange County by Gene Autry after his seven successful years in Baltimore, is that Weaver was rumored to come with him and be christened the next Angels manager, replacing Lefty Phillips, who, at that point, was only the second manager in the franchise’s history since 1961.

Perhaps discussions were had with Dalton and Weaver, but when Del Rice (’72), Bobby Winkles (’73 and ’74), Whitey Herzog (end of ’74) and Oakland-deposed Dick Williams (’74 to ’76) ended up Dalton’s choices, California dreams of Weaver waned.

That rumor isn’t addressed in John W. Miller’s book, so we’ll leave it at that.

Since the release of Miller’s chart-topping, best-selling bio sure to capture baseball writing awards when they are doled out this winter, a slew of glowing reviews, starting with the Baltimore Sun, New York Times and Washington Post, already make this a stand-up triple.

But with Weaver wearing No. 4 in honor of his favorite player, 1940s St. Louis Cardinals shortstop Marty Marion (confirmed on page 110), this quickly becomes both an insider- and outside-the-park four-bagger.

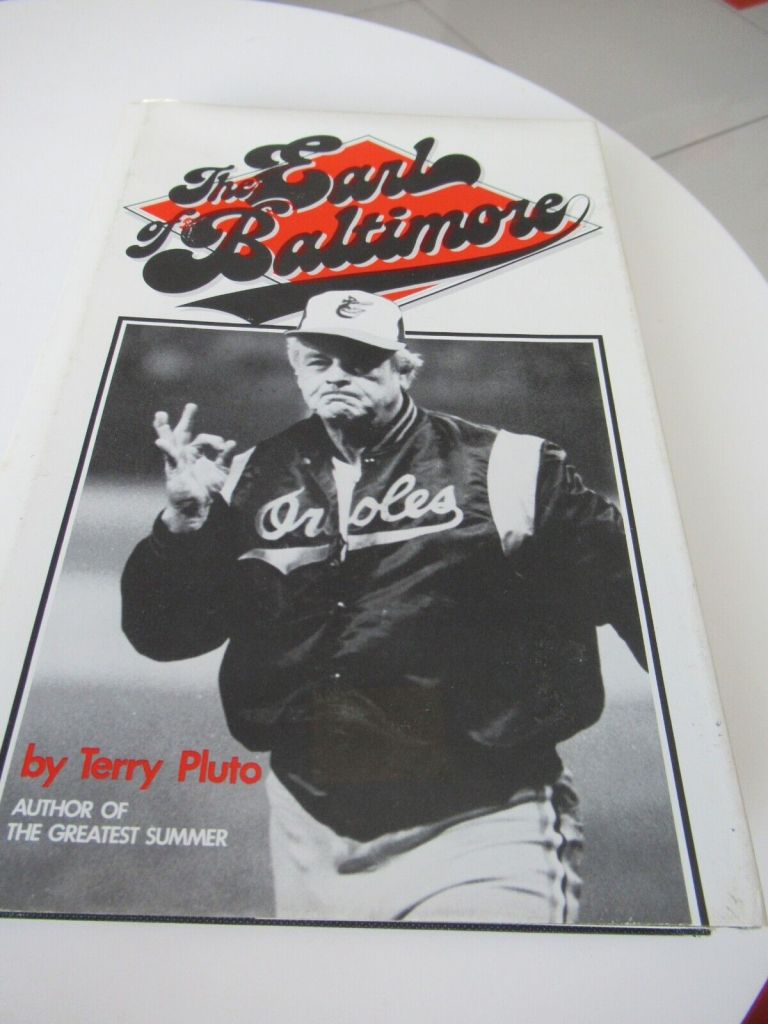

All the praise is justified for Miller, who added 200 interviews to his research of the Earl of Baltimore on top of Weaver’s two previous memoirs and a 1981 bio from Terry Pluto titled, ahem, “The Earl of Baltimore.”

What gives this Weaver book its true grit is Miller’s tempered writing style, not overwhelming the storytelling, but inserting the right fact at the right place to move it along. Editing information down is just as vital to a reader’s enjoyment as adding new pieces of detail previous misplace or forgotten as narratives are shaped through the years.

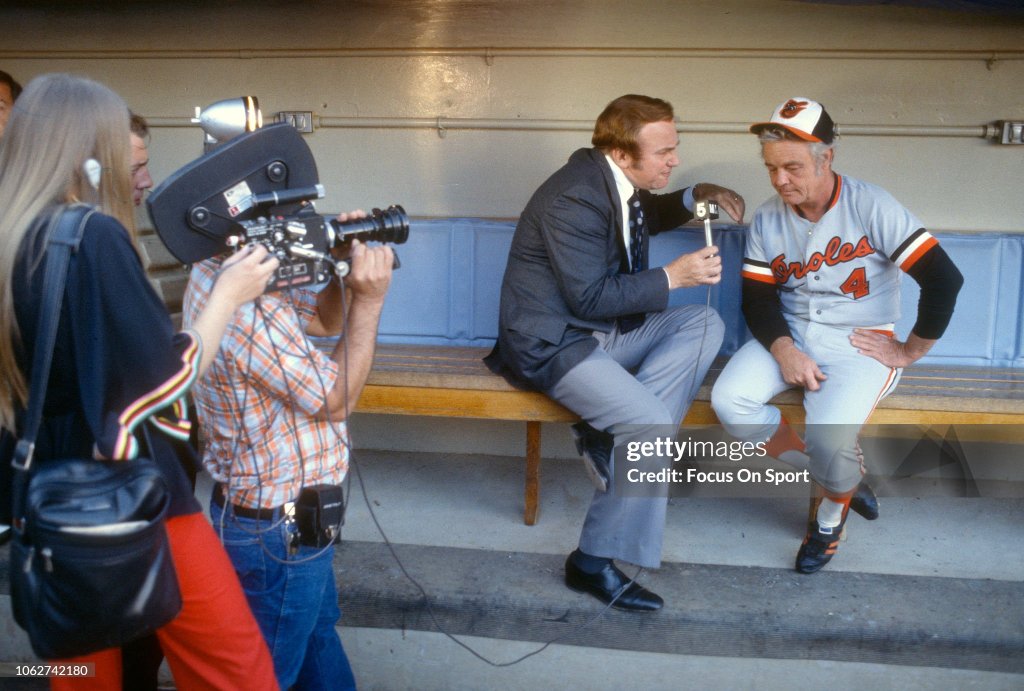

To capture the essence of Weaver’s successful run not just as the Orioles’ manager from 1968 through 1982, then coming back for the ’85 and ’86 seasons, it’s also how he developed his philosophy as a chain-smoking minor-league manager who was far ahead of the game with using data research and tendencies very primitive at that point.

That he only won one World Series title (’70) is testament still to how tough the slog can be, despite his four AL pennants (’69, ’70, ’71 and ’79), five 100-win seasons, 11 seasons of 90 wins or more, and 1,480 wins accumulated over 17 seasons — pointed out on his 1996 Hall of Fame induction plaque. And his .583 winning percentage ranks fifth among managers who served 10 or more seasons in the 20th century.

And, for a brief time, Weaver was able to tame the legendary Steve Dalkowski, who might have impacted his career W-L record even more dramatic had he not blew out his arm (yet became the basis of Ron Shelton’s rookie flamethrower in “Bull Durham.”)

Even if you think you know all you need to know about the 5-foot-6 “pepperpot” (as he was described in an Associate Press obituary when he died in 2013 at age 82 while on a Caribbean cruise), note that Miller started this process as he wrote Weaver’s obit for the Wall Street Journal (and he explains in a recent post for the Bird Tapes substack).

Miller admits the book’s title “is not a statement of fact, but a slanted swing, exaggerated to make a point. Earl Weaver reigned supreme — the only manager to last with one team during the entire 1970s — when baseball managers were American royalty and powerful operators within the game, sometimes bigger stars than their players.”

The blurbifications from the likes of George Will, Ken Burns, Ron Shelton, Jonathan Eig, Tom Verducci and Frank Cashen (“he was a fucking genius”) bode well as well for those who somehow are on the outfield fence about this.

It’s Weaver’s understanding how he could game the system with stellar pitching and waiting for that three-run homer to get him out of a mess. Its why he was moved from the Orioles’ first-base coach to its manager at the ripe age of 37.

When the Baltimore Orioles closed Memorial Stadium before moving to Camden Yards, Weaver was the last person introduced after a long line of Orioles’ former players and personnel. That’s how much he was beloved — Lasorda-esque of the East Coasters. He even gave them a little show by kicking dirt all over home plate before it was pried out and moved across the city to the new park.

Weaver deserves this final assessment, and Miller had the resources to track down those still around who could capture him best. Another reminder why books like this need to be done sooner than later. Things can quickly disappear into the cornfield.

And hopefully, you’ve noted by now, wee refrained incorporating any of the typical Weaver-type photos of him violently arguing with an umpire, images that seem to accompany almost everything ever posted about him. That was his showmanship. That really wasn’t so much who he was. Emphasize the man and the method behind all that, and you’ve posted a W.

How it goes in the scorebook

A fortunate Miller’s crossing.

We’d like to think a Hall of Fame player/manager like Miller Huggins would have embraced these two works by Scott Miller and John W. Miller with a giant bear hug.

So much learned, so much absorbed, about how this role has changed, but not been marginalized as some may think.

Full disclosure: We appreciate that John W. Miller reviewed our book, “Perfect Eloquence: An Appreciation of Vin Scully” for National Catholic Reporter.

If Scott Miller would someday like to add an essay on his interactions with Scully, perhaps for the revised softcover, I’m all in.

Or, maybe Scott Miller can expand on this nugget he has in the last chapter of his book: Did you know that Sparky Anderson came pretty close to once becoming the Angels’ manager?

In the epilogue, Miller explains how prior to the 1997 season, Angels GM Bill Bavasi hatched an idea that Anderson, at 63 and was a year removed from his final season in Detroit where the Tigers finished 60-84, could come. Bench coach Joe Maddon, then 42, who would be the manager in training.

Bavasi set up a meeting with Anderson and Angels president Tony Tavares.

“But then Sparky ordered soup,” Miller writes. “And as he drew his hand to his mouth during lunch, his arm shook and some soup splashed. That was the end of that idea.”

The Disney-owned Angels hired Tavares to maintain its corporate image and “an older man with the shakes as manager did not fit that image.” Bavasi later told Miller: “I think it was just somebody who didn’t know Sparky and saw him for the first time. You can’t blame Tony. You’d have to have known Sparky to say, ‘I’m not worried about this, it’s been this way for 10 years’.”’

Instead, Anderson became a TV analyst for the Angels, for two seasons, on Fox Sports West, and couldn’t withstand the drive from his Thousand Oaks home, or the fact he was chastised one night for saying a wild play on the field looked like “a Chinese fire drill.” Anderson died in 2010 at age 76.

You can look it up: More to ponder

== Scott Miller’s passing at age 62 on June 20 from pancreatic cancer resulted in may tributes posted about his work. One poignant post by Mark Whicker to not only review “Skipper” but also incorporate this:

“Scott was scheduled to return to Cooperstown on June 12 and talk about “Skipper,” as part of the annual Author Series at the Hall of Fame. He was entering hospice care at about that time, and he died last Saturday, only 62. His wife Kim and his daughter Gretchen, in their grief, assuredly know how much he adored them.

“Skipper” is the last thing Scott gave us. It’s revelatory, funny and clarifying. It also hums with enthusiasm, an endangered resource that Scott had in abundance. It’s a shame more people didn’t know him, but maybe if you buy this book, you will.”

== Scott Miller talked to TheFansFile.com about Dave Roberts and the access the Dodgers manager gave him:

“I wanted to peel back the layers because I think one thing that fans don’t quite understand today is how many different people and different offices are pulling at the manager. I have a line in there that Roberts is so accommodating it’s like he’s made partly of taffy because the players all need things from the manager. The front office, baseball analytics meet with the manager these days, at least once a day, if not a couple times a day. Marketing department always wants something from manager. “Can you make an appearance here?” Media relations. He sets up interviews. “Hey, we need you here. We need you there.” Dave Roberts is the consummate modern manager. He’s so accommodating and does everything with such good will, and he has great relationship with his players. I wanted to hang around and show fans what a day in the life of a modern manager is like and how many people are pulling at him. I wasn’t stunned by anything just because I’ve been covering the game for 35 or 40 years now. That said, it’s still surprising. Really, among the things that struck me with Dave Roberts was in Dodger Stadium, they’ll bring some VIPs down on the field during batting practice. Dave stops by and visits with those people while batting practice is going on. If the marketing department would have said, “Hey, we got a bunch of VIPs back on the field. We need you to stop by during batting practice,” Tom Kelly, Earl Weaver, Sparky Anderson might have punched the media relations guy or marketing guy in the nose, whereas today it’s just part of the drill and Dave is the best at it. He went back and schmoozed with people, got his picture taken even while batting practice is going on. One of the nights I was there, one guy had a friend on FaceTime. Dave even went on FaceTime and said hello to the friend.”

== More on the managerial side of things, if you like your skippers to get into some soul-soothing prose:

= “Hurdle-isms: Wit and Wisdom from a Lifetime in Baseball,” by Clint Hurdle, Wiley Publishing, $22, 144 pages, released Feb. 11, 2025; at the publishers’ website and Bookshop.org

Just hired back by the Rockies as their hitting coach, Clint Hurdle posted a 1,269-1,345-1 record in 17 years covering Colorado (2002 to 2009) and Pittsburgh (2011 to 2019). He had one National League pennant, in 2007, when the Rockies were 90-73. He also had two 90-plus win seasons with the Pirates (94-68 in 2013 and 98-64 in 2015) with nothing to show for it. Interesting, his Baseball-Reference.com profile shows he got calls overturned on 52.1 percent of his challenges, with a high of 63.3 percent in ’17.

His managerial style came from experience gleaned in a 10-year MLB career, launching at age 19 in 1977 with Kansas City with a very over-hyped SI cover, then stops in Cincinnati, the New York Mets and St. Louis. His managers included Whitey Herzog, Jim Frey, Dick Howser, John McNamara, George Bamberger, Frank Howard and Davey Johnson.

So now Hurdle is famous for saying things like “multi-tasking makes me feel multi-mediocre” or “the smallest package in the world is a person wrapped up in himself.”

There are 25 of these fortune-cookie quips to contemplate. Leave it laying around in the Rockies’ clubhouse bathroom and see what happens.

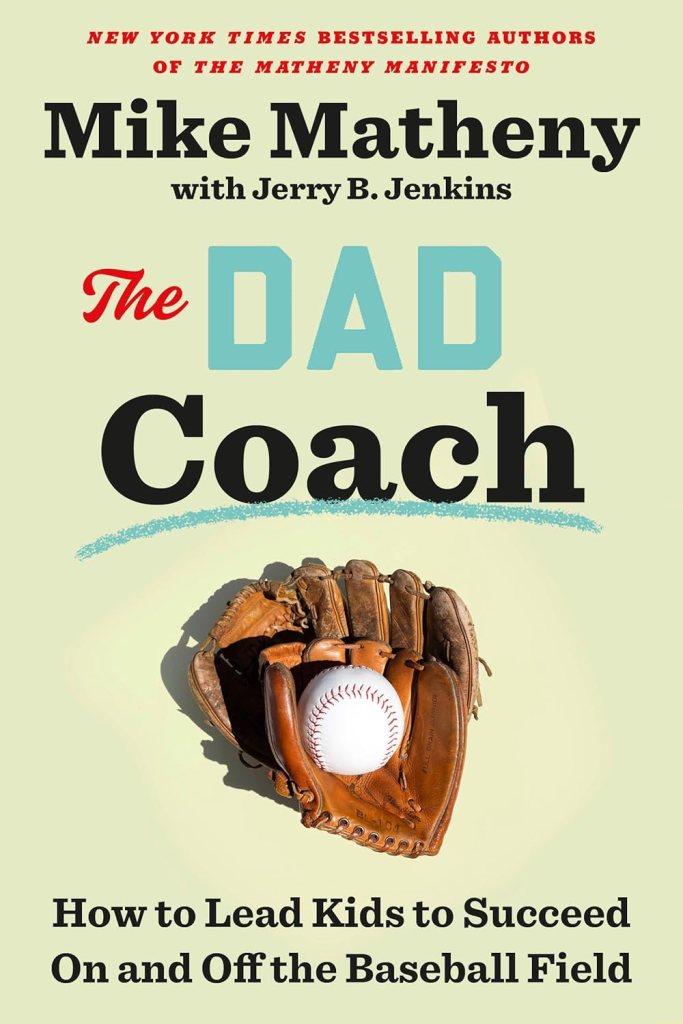

== “The Dad Coach: How to Lead Kids to Succeed On and Off the Baseball Field,” by Mike Matheny with Jerry Jenkins; Crown Books/Penguin Random House, $29, 240 pages, released March 25, 2025. At the publishers’ website and Bookshop.org.

Rolling forward after the 2015 release of “The Matheny Manifesto: A Young Manager’s Old-School Views on Success in Sports and Life,” here is something presenting more teachable moments on the local levels, where instilling discipline and humility is much more valuable than a participation trophy. It also advises on how volunteer coaches can really get the full enjoyment of what they’re trying to achieve, along with QR codes that lead to instructional videos.

Also know: Matheny has written an open letter to parents of kids who play the game: “I’ve always said I would coach only a team of orphans. Why? Because the biggest problem in youth sports is the parents. But here we are, so it’s best I nip this in the bud. I’m going to do this, I’m asking you to grab the concept that this is going to be ALL about the boys.”

And girls?

It’s somewhat curious why Matheny, just 54, with all his wisdom, is out of the MLB circuit after seven seasons in St. Louis (2012 to 2018, including the 2013 NL Pennant and a 100-win season in ’15) plus three more in Kansas City (2020 to 2022). His 756-693 career mark includes a 49.2 percent overturn rate on challenges. The four-time Gold Glove winning catcher put in 13 years (and a -0.5 WAR) with Milwaukee, Toronto, St. Louis and San Francisco, and even with a .239 career batting average, he was a considerable asset to any roster at his peak.

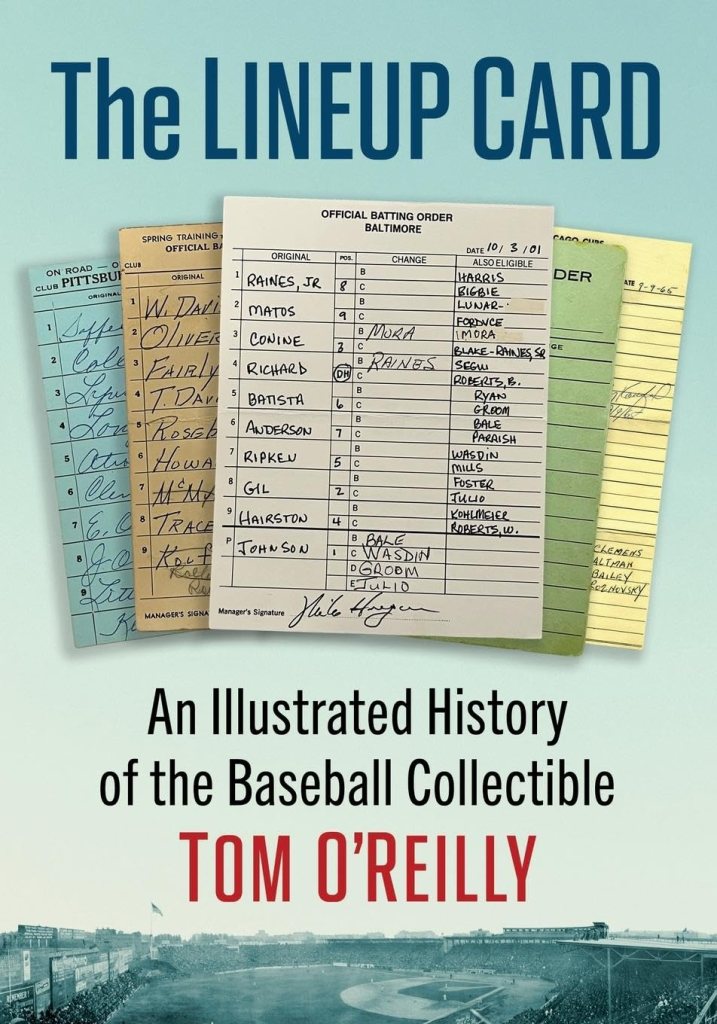

== “The Lineup Card: An Illustrated History of the Baseball Collectible,” by Tom O’Reilly; McFarland Books, $39.95, 263 pages, 203 photos, released August, 9, 2024. Best found on the publisher’s website and BookShop.org

You can’t be a manager on any level without knowing how to fill out a lineup card. The beauty is seeing originals used over the years as this sort of Magna Carta quality that makes us wonder why they aren’t behind glass somewhere. Many modern-day lineup cards can be bought and sold by collectors. There is definitely an artistic aspect just gazing upon them, the managers’ penmanship, how tidy they have to be to write in the margins. From majors to minors and many below that, it’s a visual thrill to see not a scorecard of a game played but the formal information that needs to be submitted (and can backfire if someone isn’t monitoring it closely) and becomes scorecard-ready. Would have loved to seen this in a super-sized coffee-table presentation.

= Steve Lombardi posted in 2010 a list of “28 Guys Who Never Would Have Worked for Earl Weaver,” because they made too many outs (and, yes, Mario Mendoza is on the list, but so is two-time AL Manager of the Year Kevin Cash, a -3.1 WAR catcher in nine MLB seasons, plus future manager/coaches such as John Vukovich, Ned Yost and Luis Pujols.)

= Coming up in 2026: Writer Steve Kettman tells us he is working to finish a bio with Dusty Baker coming out from Crown books in the spring/summer, as well as his own book about the life of managers published in the fall from Grove Atlantic.

== If we were the manager of this post (which we are), we’re calling in this closer:

1 thought on “Day 12 of 2025 baseball book reviews: Effective skippering”