“Selling Baseball: How Superstars

George Wright and Albert Spalding

Impacted Sports in America”

The author: Jeffrey Orens

The details: Rowman & Littlefield, $35, 274 pages, released Feb. 4, 2025; best available at the publisher’s website and Bookshop.org

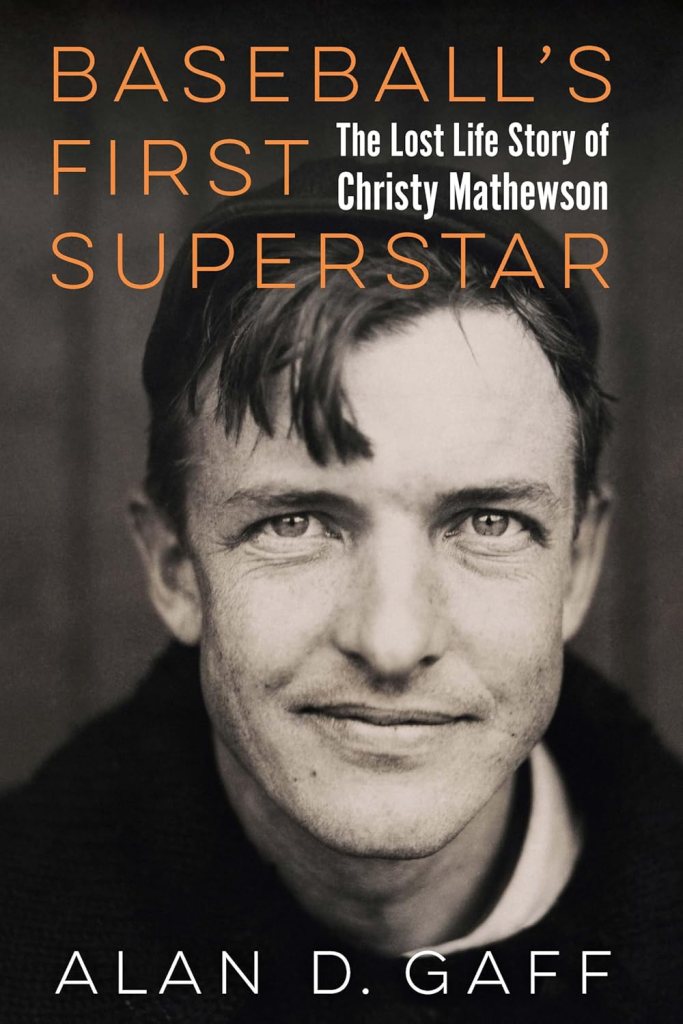

“Baseball’s First Superstar:

The Lost Life Story of Christy Mathewson”

The author: Alan D. Gaff

The details: University of Nebraska Press, $32.95, 240 pages, released in May, 2025; best available at the publishers website, the author’s website and Bookshop.org.

A review in 90 feet or less

Focus just on baseball’s language, with all its over-modulated adjectives and supercilious discussions. From that, how does one decide when a player moves ahead of the line from a “star” to a “superstar”?

Preferably, a superstar without a capital “S,” which seems to be treading far too close to Superman territory.

A year ago, Joe Reuter of the Bleacher Report listed his “Definitive List of MLB Players Who Deserve to Be Called a ‘Superstar’,” and established the guideline: “Being a superstar athlete is about more than just on-field performance, as major market exposure, marketability and highlight-reel skills can all help elevate a talented player to that next tier of stardom.”

They are trend setters and stop-and-watch performers, heightened by social media and all the other applicable influencers of the day.

From his template, Reuter rooted out 15 “superstars” who checked all the boxes, which are, and in alphabetical order: Ronald Acuna Jr., Jose Altuve, Mookie Betts, Gerrit Cole, Freddie Freeman, Vlad Guerrero Jr., Bryce Harper, Aaron Judge, Francisco Lindor, Manny Machado, Shohei Ohtani, Corey Seager, Juan Soto, Fernando Tatis Jr., and Mike Trout.

We’ll be the judge of this list. We’d cut it by more than half — Betts, Harper, Judge, Ohtani and Trout. We might also be tempted to add Clayton Kershaw, Max Scherzer and Justin Verlander — three soon-to-be Hall of Fame players with career resumes that announce their arrival.

And how are you not entertained by Elly de la Cruz?

To lay some groundwork for this, Reuter did a 2018 “power ranking” of the top MLB stars from every decade since the 1900s. It was a Top 10 list for each 10-year frame, but here are the tip-top names: Christy Mathewson, Honus Wagner and Cy Young in the 1900s; Ty Cobb and Walter Johnson in the 1910s; Babe Ruth, Rogers Hornsby and Lou Gehrig from the ‘20s; Jimmy Foxx with Gehrig in the ‘30s; Ted Williams, Stan Musial and Joe DiMaggio from the ‘40s; Mickey Mantle, Willie Mays and Musial from the ‘50s (failing to include Jack Robinson); Mays, Hank Aaron and Sandy Koufax from the ‘60s; Tom Seaver, Johnny Bench and Pete Rose from the ‘70s; Nolan Ryan and Mike Schmidt from the ‘80s; Ken Griffey Jr., and Barry Bonds from the ‘90s; Albert Pujols, Bonds, Alex Rodriguez and Derek Jeter from the 2000s. Again, we subjectively excluded many to try to skim the top for the cream.

At the start of each season, MLB Network, Fox Sports and ESPN also put forth (maybe as ways to generate interest, maybe it is legit) their lists of the “Top 100 players” at that moment. Infer which ones are super.

Ohtani made it as No. 1 on all three polls for 2025. MLB.com and Fox had Judge at No. 2, while ESPN.com had Bobby Witt Jr., second on its list (with Betts third and Judge fourth).

Not wanting to leave it to one or two cross pollination of writers, we also asked AI to see what it might produce as a current superstar list based on access and accumulation of all that’s polluting the internet machine.

It replied in what reads to be absolute dreary argumentative statements:

There was also a Reddit post during COVID that saw someone claiming to be so bored he took the time to go all the way back to the 1870s to start his lists of stardome. That can be helpful here to at least prove a point.

For the 1870s, he took Ross Barnes as the top hitter (.371 with Boston, Chicago and Cincinnati) and Tommy Bond (Brooklyn, Hartford and Boston) as the premiere hurler. In the 1880s, it was Dan Brouthers and Tim Keefe. In the 1890s, it was Billy Hamilton and Amos Rusie (over Kid Nichols or Cy Young).

The 1890s introduced Mathewson, winner of two Triple Crowns with an ERA of 1.98, with Wagner, winner of seven batting titles. Mathewson, we will accept as a correct answer, as it fits into this review narrative. But the absence of George Wright and Albert Spalding from the 1870s we find curious, if not paying attention to what was somewhat obvious at the time.

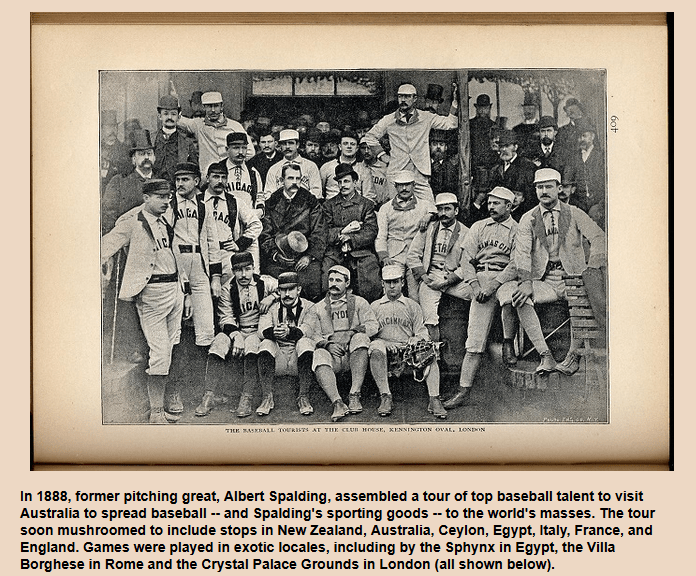

In “Selling Baseball: How Superstars George Wright and Albert Spalding Impacted Sports in America,” you’re supposed to be sold on the concept of “superstars” as a way to attract attention. They’re super more for what they did with their baseball business acumen on top of their playing ability. That’s the total package we’re assessing here.

Orens’ work is more of a dense, somewhat repetitive read, of what life was like in the drunk-and-carousing-and-gambling-inflicted National Association of Professional Base Ball Players — NA for short — in the post-Civil War era.

When Harry and George Wright aligned with Albert Spalding on the Boston Red Stockings to form something of a dynasty in the 1870s. That would seem to be a time when playing baseball was a bit trivial with all happening in this war-torn country, but we’ll give them credit for trying to normalize the game that had been used as recreation for the Union troops en route to their extra-inning victory.

Hurray for Captain Spalding for capitalizing in a true American business story.

Ross Barnes is also given his due as Spalding’s friend and “an outstanding player in his own right” on page 83, as George Wright and Spaulding heap their praise of Barnes as “one of the best all-around players the game has ever developed.”

Extra credit to Orens explaining how George, as an infielder, and Harry, as a pitcher and outfielder, used to deceive opposing hitters and runners with infield flies they purposely dropped and fielded.

By 1895, the National League came up with the “Infield Fly Rule.” By 2025, all its gray areas have not been clarified.

Their superstar status came more after they couldn’t play any longer but wanted to promote the game through the sales of a standardized equipment. And show the world what this was all about.

Their work in sales and marketing did in fact make an impact, and their contributions are rightfully chronicled here. In a book that sells itself on the topic alone.

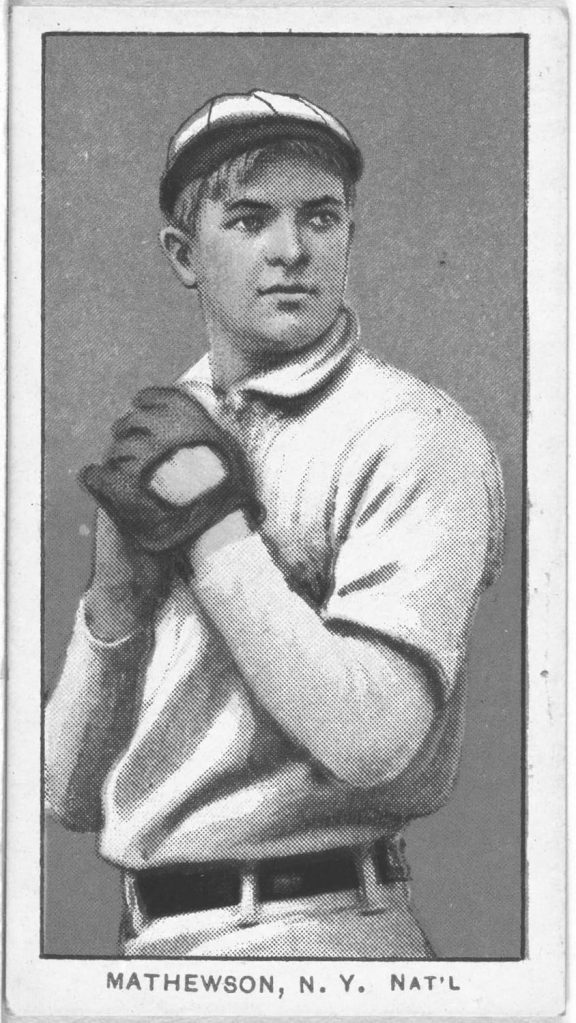

With “Baseball’s First Superstar: The Lost Life Story of Christy Mathewson,” super researcher Alan D. Gaff comes through first with his constitution of why he would take Mathewson over Wagner, Walter Johnson and even Babe Ruth as the game’s “first” main attraction/certified super star. It’s based as much on how the power of newspaper coverage aligned with him better than others, noting Mathewson’s college education who eventually gained World War I hero status to go with his clean-image hobbies of game-hunting, trapshooting, chess, golfing, acting in silent movies, baritone singer, writer, and flower enthusiast, inspiring board games and brand loyalty.

And, his good looks. Just look at that cover shot of “Big Six,” in a Mark Harmon-like pose, with his side hustle of promoting pipe tobacco and these new things called automobiles.

Others may point out as well that Mike “King” Kelly may be more the “first” in the superstar realm, but without any historic value, the arguments fizzle out. Mathewson met the moment for the entire U.S. population when baseball wasn’t seen so seedy, and he helped tremendously in rehabilitating that image. And performing on the biggest New York diamonds was even more impactful. Also consider how later MLB players, particularly Tom Seaver, so admired Mathewson’s impact on his own career.

Gaff then presents a 45 chapters over some 130 pages to recount a series written about Mathewson for a syndicated newspaper subscribers that was likely thought to be lost, or never to have known existing. Jane Mathewson, his widow after her husband died at age 45 in 1925 from tuberculosis, approached prominent sportswriter Bozeman Bulger, the “Cervantes of his profession,” who had known Mathewson for 20 years, and that’s where this work was generated — from Jane’s input and lending access to writings Christy has done himself but never had published.

Imagine these stories appearing at the time when Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig were beginning their run with the New York Yankees and capturing headlines.

It’s as fascinating a read as what Tim Manners pulled together for “Schoolboy: The Untold Journey of a Yankee Hero” using the unpublished works of Waite Hoyt. That was one of the surprise enjoyable reads of 2024.

Appropriately, Manners gives this blurb: “Alan D. Gaff gifts us with a forgotten biography and memoir of one of the grandest twirlers of all time: Christy ‘Gumboots’ Mathewson. Yes, Gumboots. Read on!”

This kind of research follows up on what Gaff did in 2020 when he re-displayed for today’s readers a newspaper series ghostwritten for Lou Gehrig.

Give Gaff enough time, and he’s liable to uncover even more of these hidden gems.

How it goes in the scorebook

Star-struck.

We appreciate how Gaff, on page 31, turns to superstar newspaper scribe Grantland Rice as the first of his ilk to even use the word “superstar” as a way to equate an athlete to someone who is of the highest of profile in the field of acting, film or vaudeville. And from any sort of timeline, Mathewson exiting the game in 1915 as Babe Ruth was entering as a nifty pitcher who would become an extraordinary hitter is the one who appears to have taken that paper route and amplified its meaning.

They probably deserved to earn a salary more than the U.S. president for the unity the brought to society through baseball.

You can look it up: More to ponder

== An interview with Orens by Jeffrey Lambert on The Rounds Substack/podcast.

== We regret missing one of the more recent performances of Eddie Frierson’s Off-Broadway performance “Matty: An Evening With Christy Mathewson,” when he returned to the Santa Monica Playhouse in February of 2024. A transcript of his performance has been available since 2017 to buy and enjoy.

== University of Nebraska Press/Bison Books continues to include Mathewson’s 1912 original version of “Pitching in a Pinch: Baseball From the Inside,” with the original muddy typeface, in its catalogue after coming out with it in 1994, with an introduction by Eric Rolfe Greenberg.

== Many consider Ray Robinson’s 1993 book, “Matty: An American Hero” from Oxford University Press to be the ultimate in capturing the life and times of Mathewson. Also consider: “The Old Ball Game: How John McGraw, Christy Mathewson, and the New York Giants Created Modern Baseball,” by Frank Deford in 2005; “Christy Mathewson, the Christian Gentleman: How One Man’s Faith and Fastball Forever Changed Baseball,” by Bob Gaines, published in 2014; “The Player: Christy Mathewson, Baseball, and the American Century,” by Phil Seib in 2003.

1 thought on “Day 14 of 2025 baseball book reviews: Before a superstar smelled his (or her) armpits for validation”