This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 39:

= Roy Campanella: Not-quite-Los Angeles Dodgers

= Sam Cunningham: USC football via Santa Barbara

= Mike Witt: California Angels via Anaheim Servite

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 39:

= Milt Davis: UCLA football

= Willie Strode: Los Angeles Rams via UCLA

= Chris Kluwe: UCLA football

The most interesting story for No. 39:

Jim Hill: Los Angeles sports TV anchor (1976 to present)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Hollywood, every major sports venue in Southern California

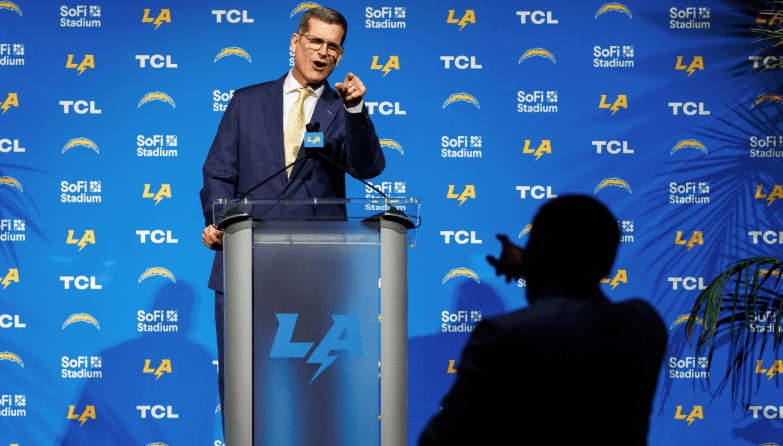

As by protocol for any sports televised press conference in Southern California over the last several decades, Jim Hill was dutifully called upon to ask the first question when the Los Angeles Chargers reeled in the media for a Feb. 1, 2024 announcement, moving it from their Costa Mesa headquarters to the YouTube Theater in Inglewood next to SoFi Stadium.

Jim Harbaugh, who had just won a national championship at the University of Michigan, was introduced as the Chargers newest head coach.

“Coach, I’m Jim Hill, KCAL-9 news … congratu …” is how Hill began.

“The legend,” Harbaugh interrupts. “Of course I know who you are.”

“No, no, no, you’re the legend,” Hill responds.

“You’re the legend,” Harbaugh repeats.

Hill continued by congratulating Harbaugh, wishing him good luck and noted that by seeing “all of us here today, what does this tell you about how popular this choice is by the Chargers to make you as a the head coach, and, the great expectations that come?”

“Well, thank you for that question, Jim,” Harbaugh replied. “And you are a legend.”

Harbaugh got in the last word.

As the Chargers began honored players from its past during Black History Month in that same February of 2024, Hill was a natural to profile. It started “Before legendary sports anchor Jim Hill got his start in television and became one of the well-known faces in Los Angeles and around the country, he was the one being interviewed.”

There’s that “legend” thing tossed around. And the Chargers have the rights to Hill’s No. 39 origin story, how it launched his sports broadcast career –a byproduct of the work ethic he established as an NFL player — and how he became a role model of African-American success in the community, setting him apart more than any other in Southern California local TV history.

The background

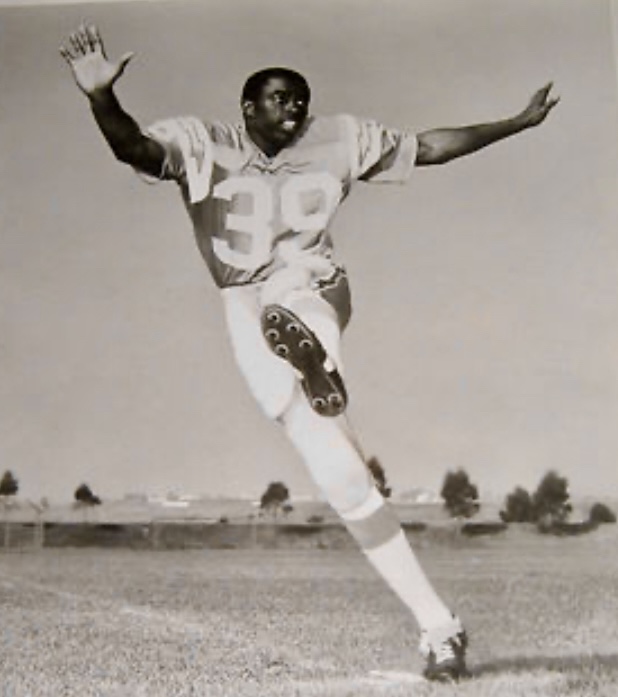

In the 1968 NFL Draft, the San Diego Chargers used pick No. 18 overall on a defensive back from Texas A&I-Kingsville, an NAIA powerhouse in the Lone Star Conference just outside of Corpus Christi in the deep southern tip of the state near the Gulf of Mexico.

Jim Hill, a 6-foot-2, 190-pounder, would be chosen ahead of future Hall of Fame defensive tackle Curley Culp, future Hall of Fame quarterback Ken Stabler, future Hall of Fame tight end Charlie Sanders, future Hall of Fame defensive end Elvin Bethea and future Hall of Fame offensive tackle Art Shell.

At Texas A&I-Kingsville, Gene Upshaw taken in the first round, No. 17 overall, by Oakland’s Raiders in 1967, so the school was on the NFL scouts’ radar. Upshaw became a pretty big deal in the NFL players association hierarchy.

In 1976, Jim Hill’s younger brother, David, would be drafted out of the same school, a tight end that spent five of his 12 NFL seasons with the Los Angeles Rams.

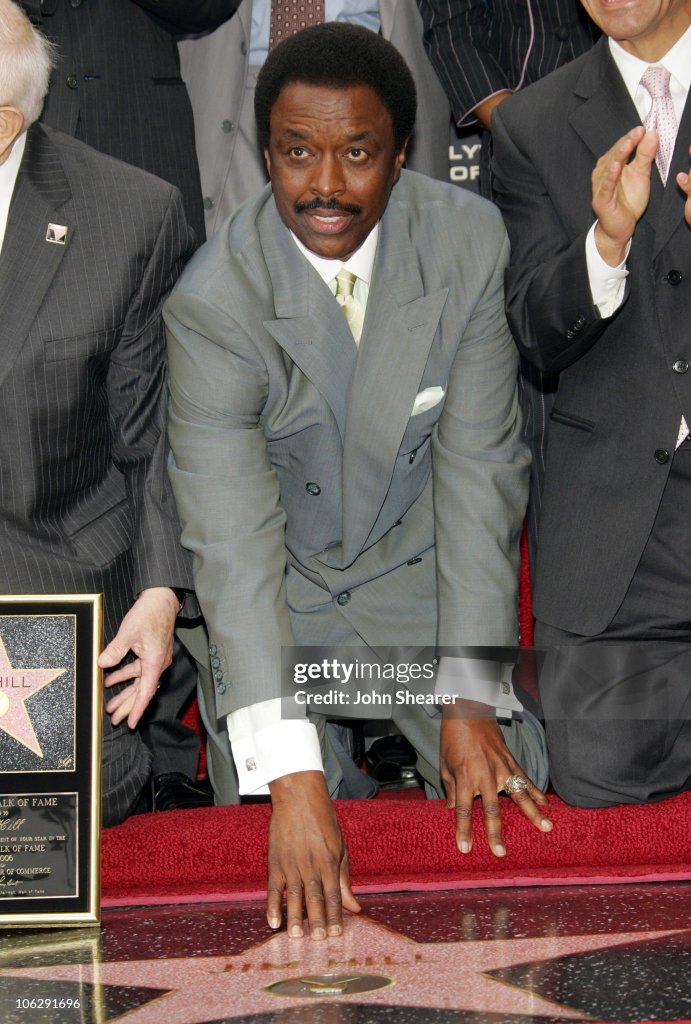

Neither would eventually get their star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame as Jim Hill did.

That Hill even made it to Texas A&I, whose nickname was the Fighting Javelinas, is its own survival story.

“I knew how lucky I was because of the environment I grew up in,” Hill told us as we crafted an essay for the book, “Perfect Eloquence: An Appreciation of Vin Scully,” in 2023. “I came from the end of the dead-end street in Texas. If I hadn’t played football, I would be dead today. Sports saved me.”

Hill’s progress in college from 1964 to ’67 as a football and track-and field athlete taught him to prioritize.

“You know in college when you have to take a biology class?” Hill told The Athletic reporter Rich Hammond. “In your biology class, you have to dissect a frog. My lab was from 1:30 to 3 (p.m.) on Mondays. We had football practice — had to be on the field at 4:15. So I’ve got to figure out a way to get out of this lab. This ain’t working. We just had a bad game on Saturday, and I know the coach is going to run the hell out of us when we get out there on Monday.

“So I’ve got this idea. We have to dissect a frog. So I go and I get a cherry bomb firecracker. My lab station was in the back of the room, by a window. I would occasionally fall asleep because the wind would come in and I’d doze off. So, I thought, I’m getting out of here. So I get the scalpel and I slit a hole in the frog between its legs. I put the cherry bomb firecracker down in there and sew it up. The wick was sticking up about, oh, a little more than a quarter of an inch, and the frog was on a gurney. I lit it and I rolled it down the aisle. It got about halfway up the aisle, and — boom! And it was a big frog. It was a bullfrog. The girls are just hollering and screaming. ‘It’s in my hair!’ The professor, at the front of the room, was writing on the blackboard. He never turned around. He said, ‘Mr. Hill, get out’.”

A wiser faculty advisor connected Hill with the general manager of the Kingsville, Tex., radio station, KINE. That gave Hill a taste of working as a DJ and talk-show host.

When the Chargers became Hill’s employer, it happened that UHF station that carried the team’s games in San Diego was KCST-Channel 39. The station execs heard that Hill had some experience in broadcasting, and it inquired if Hill might be part of its programming lineup. To help with the branding of this venture, Hill was given No. 39. He did a music show called “Mr. 39’s Talent Night,” similar to “American Bandstand.

“I also wore No. 39 in college,” Hill added. “Isn’t that a sign that somebody upstairs is looking out for you? That’s not planning.”

In four seasons with the Chargers, Hill started 38 of 42 games, had seven of his nine interceptions as a rookie free safety and three fumble recoveries.

Harold Greene, a cameraman for a San Diego TV station who would become a news anchor in L.A. years later, said he remembered Hill’s first game.

“He strolled by the referee and said, ‘Did you bring your glasses today?’” said Greene. “Then in the fourth quarter, the referee called pass interference on Jim, and the flag landed right on his chest. Jim couldn’t believe the call, and the referee said, ‘It was pass interference, and I saw it clearly.’ ”

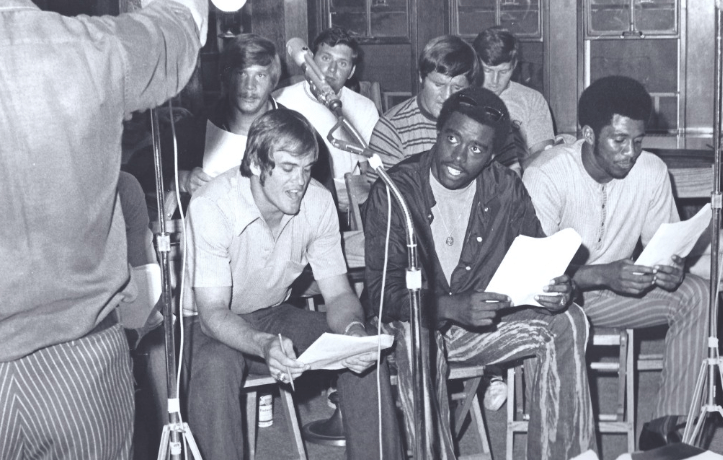

During three seasons in Green Bay, Hill, moved to safety, found work at the local WBAY-TV station, which carried Packers games. The CBS affiliate gave him the opportunity to contribute to its Monday and Tuesday evening newscasts.

“My teammates used to tease me, but I was preparing for my future,” Hill said in 2019, when he was receiving the Lifetime Achievement Award by the L.A. Press Club.

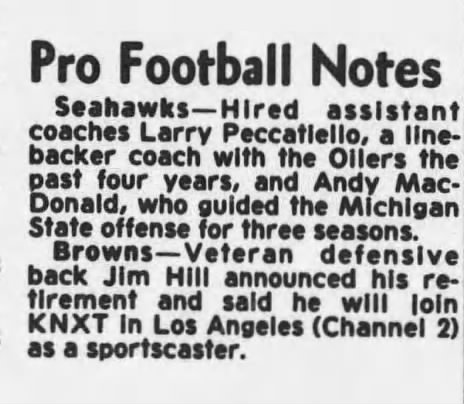

In seven NFL seasons, Hill’s only pick six return came in his final season, 1975, playing for Cleveland. A 56-yard return in the final minutes of a 36-23 upset over Cincinnati was during the Browns’ first win of the season in 10 games.

“I’ve scored four or five touchdowns with interceptions in my career, but none of them counted — there was always a penalty,” Hill (then wearing No. 49) told the Cleveland Plain Dealer after the game. “This ball’s going home with me. I didn’t even look for flags this time.”

The new career

Fresh off the football field, Hill aligned himself with agent Ed Hookstratten, who had represented talent from Elvis Presley to Vin Scully. Hookstratten lined Hill up for a job at KNXT-Channel 2 in Los Angeles in 1976, and, to prepare him, asked Scully to meet them for lunch so he could pass on some pointers on this career transition.

“He told me: If you go to a press conference that starts at 10 o’clock, be there at 9, sit in the front row and be the first to raise a hand and ask a question,” said Hill of Scully. “They’ll start acknowledging you more.”

Check.

“He taught me about common courtesy. When people stop to say hello, to ask for a photo or autograph, it takes more time to make up a reason why not to do it. Just go ahead and do it. Besides, people don’t have to say anything. So when they do, take the time to respond. It means a lot.

“He also told me: When you’re traveling, even if it’s in the middle of the night, wear a suit and tie. Always represent yourself, your profession and your race.”

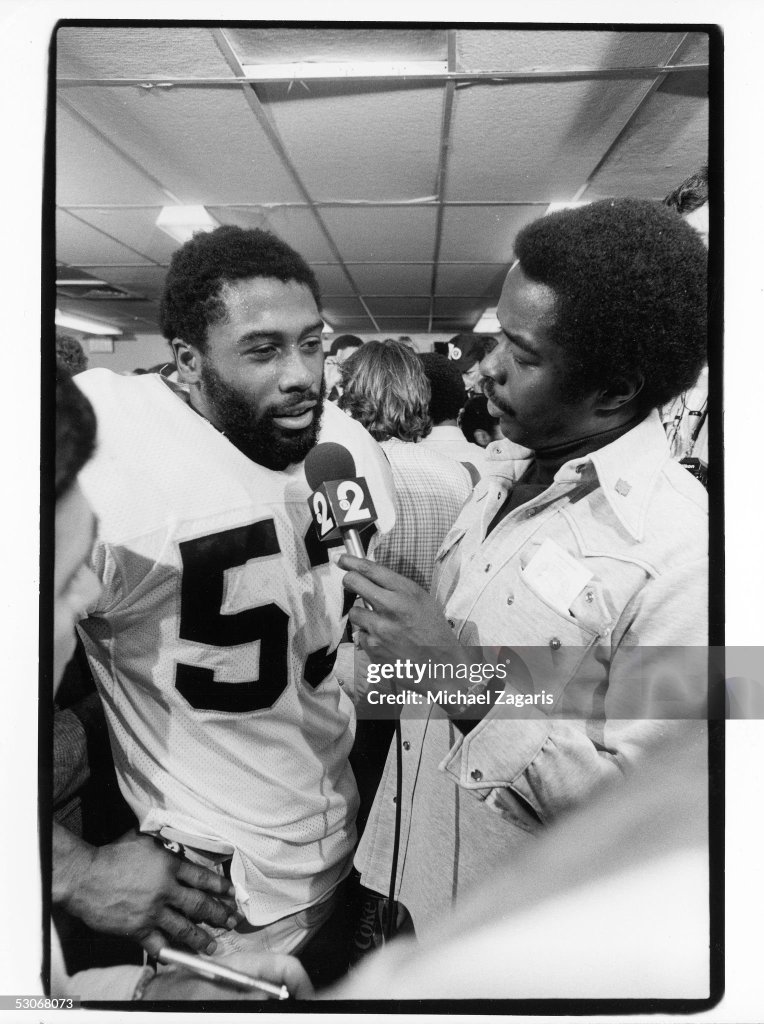

Hill’s presence as a former athlete already gave him a edge for access with almost all SoCal high-profile athlete. When KCBS gave him a late Sunday night sports wrapup show, Hill became the trusted sportscaster who could encapsulate all that happened of importance over the weekend, resulting in other local TV stations to come up with their own shows.

In 1978, Earl Woods saw Jim Hill on TV and knew he could trust him with a bit of a scoop that turned out to be an historic glimpse at the future.

“My son Tiger is getting ready to revolutionize the sport of golf,” said Earl. “He’s going to rewrite all the record books … and I want you to come down and do an interview with him.”

Tiger was 2 years old.

‘‘Well, what else is interesting about this story?” Hill asked.

Earl snapped back. “I’m a former Green Beret. Now get your butt down here.”

“This wasn’t a request,” Hill recalled. “This was an order.”

Meeting up at the driving range at Navy Golf Course in Cypress, near Los Alamitos, Hill, a left-handed swinging golfer himself, said he saw a kid “only a couple of feet tall …yet he was hitting it 50 yards, and he was hitting the ball flush every time.”

What didn’t make air: Hill tried to coax an interview out of Tiger Woods, who went quiet all of the sudden with the camera on. Hill pleaded with Tiger to talk. “My career is riding on this,” he joked. Tiger then responded: “I have to go poo-poo.”

If it turns out that Hill was the one who introduced Woods to TV cameras and the media, it’s duly noted.

“This young man is going to be to golf what Jimmy Connors and Chris Evert are to tennis,” Hill reported in his story. We believed him.

Hill had the glistening smile. The good looks. The sharp-tailored suits and pocket square. The firm handshake. And he reminded you at the end of every broadcast to “keep the faith.”

As a former athlete, he knew what it was like to experience highs and ride the lows.

Hill recalled a time in 1973 playing with Green Bay when he had made a mistake that he made he felt cost his team in a 20-6 decision at Candlestick Park against San Francisco. On the flight home, Hill said he stood up and took responsibility for the loss in front of his teammates. When reporters met the team at the Wisconsin airport, Hill said one question asked of him was baffling.

“Hey Jim, what happened last night?” a reporter asked.

Hill said he was a little miffed someone had asked him “a very stupid question.”

Several years later, Hill recalled how he headed to LAX after the Rams’ tough loss in Green Bay came after Eric Dickerson fumbled in the closing minutes. Hill said approaching Dickerson with a mike in hand caused him to flash back.

“I went up to Eric as he came off the plane. I said, ‘Well, you know, Eric, sometimes this game can make a grown man want to go and just hide for a moment.’ Eric looked at me, heard the question and talked for three minutes, expressing how he felt, how he let his team down.

“I feel it is very important to be sensitive to the people you interview,” Hill added.

Hill worked an NFL analyst for CBS in 1980, and then did play-by-play roles on regional games. He was CBS’ sideline reporter for its coverage of Super Bowl XVIII in 1984.

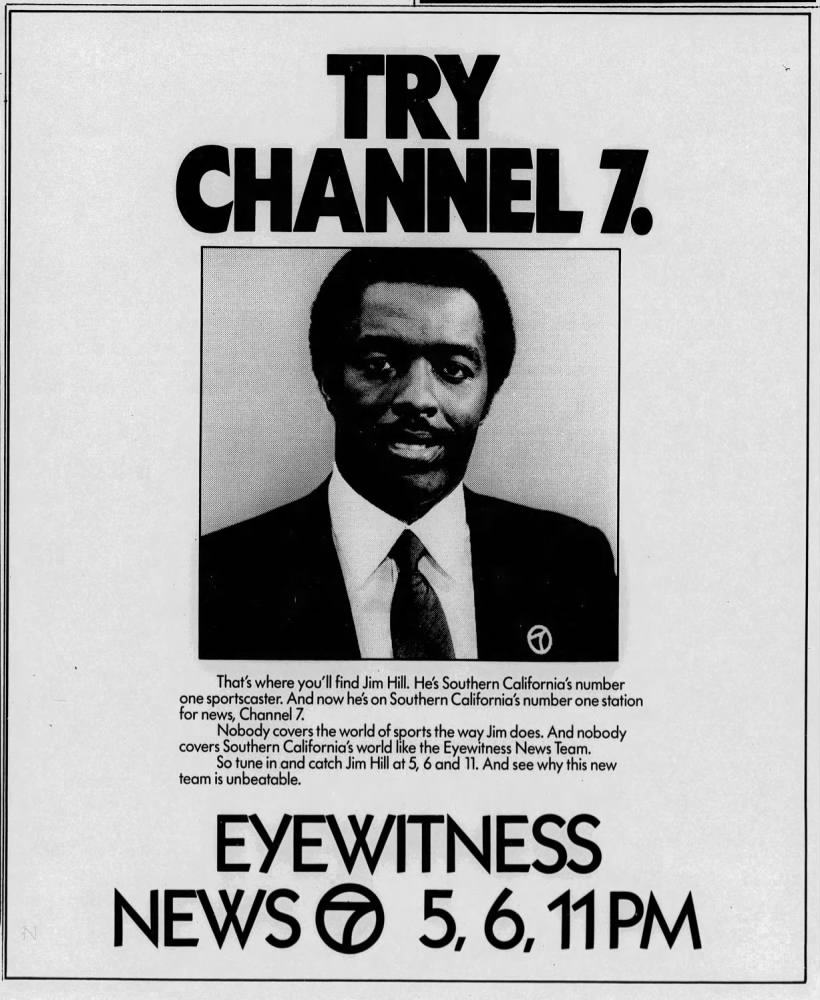

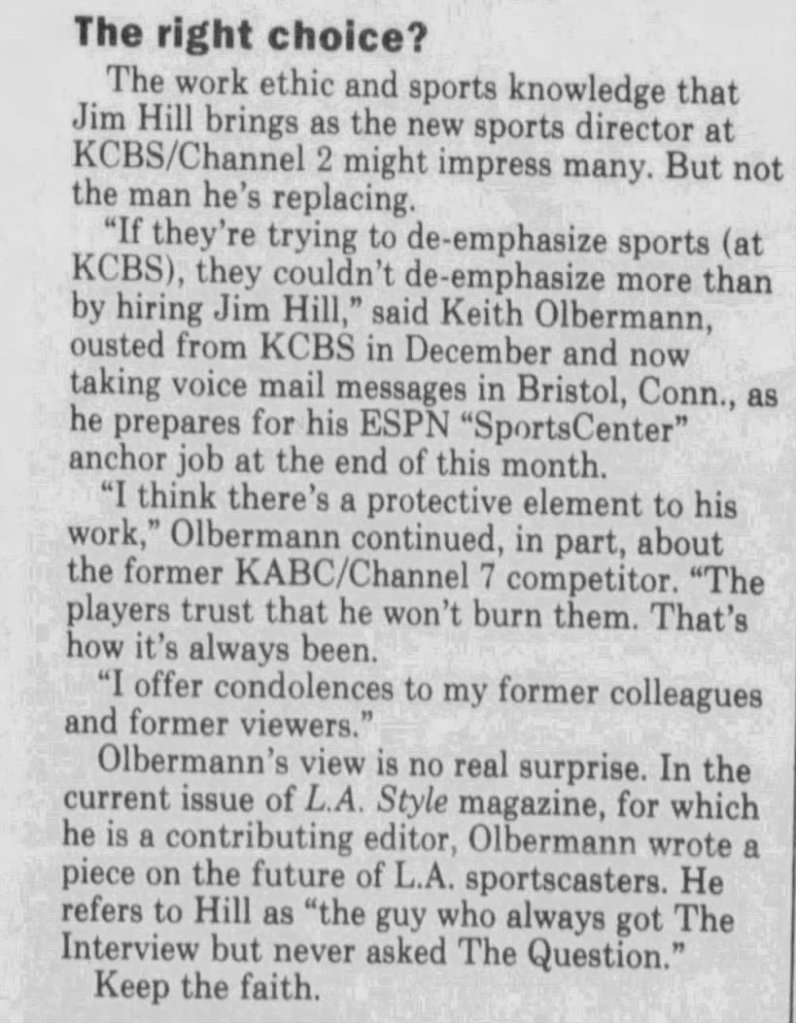

After 11 years at KCBS-Channel 2, free-agent Hill was lured to KABC-Channel 7 in 1987 for a reported $750,000 a year. That led to a five-year run anchoring the 5, 6 and 11 p.m. sports segments on the Eyewitness News, plus gave him work on ABC’s college football scoreboard show.

He was an ABC correspondent in Calgary during the 1988 Winter Olympics, as well as for the network’s coverage of Super Bowl XXII in ’88.

But in March of 1992, Hill circled back to KCBS for a role that expanded when its sports coverage merged with sister-station KCAL-Channel 9. The lure was also the ability to call NFL games again for the network.

A newspaper TV listings from a fall Sunday in 1992 would show Hill start his day with a 9 a.m. show called the “L.A. Football Company” with co-host Cindy Garvey Truhan, described as a look “at professional football in a non-traditional light.” It was followed by a 1 p.m. NFL post-game show, a (taped) 1:30 p.m. show Hill reported from Rancho Park for a sponsor’s request to get coverage of a PGA Senior Classic, a 3:30 p.m. “Sports Wrap” show, an 8 p.m. NFL post-game show and the 11:30 p.m. “Sunday Sports Final.”

Then again, this was an excerpt from a column we did on March 20, 1992:

By 2006, Hill had his Walk of Fame spot at 6801 Hollywood Blvd., not far from the TCL Chinese Theater. A place where some could have seen him in “Rocky III.”

By 2010, he was inducted into the Southern California Sports Broadcasters Hall of Fame. In 2026, the SCSB gave him another lifetime achievement award, marking his 50th year in Southern California television.

A few months prior to that, Hill received the Los Angeles Area Emmy Governors Award.

Hill’s mantra has been “get up early, go to bed late and work like hell in between. Once you find that comfort level, man, that’s when you start to have a lot of fun. I have fun every day. One of the things I love doing, besides the job, is helping in the community, just helping young kids. Because I remember what it was like being a young kid.”

In a 2020 piece for The Athletic about the most iconic sportscasters in Los Angeles — combining anyone who worked behind the mike — Hill was slotted in at No. 5 behind Vin Scully, Chick Hearn, Jamie Jarrin and Jim Healy. It noted: “For 44 years, Hill has been the face of sports television in the Los Angeles market, not only on KCBS and KABC newscasts but at seemingly every game and press conference. Hill long ago achieved the difficult balance of having local sports figures both respect and like him.”

Hill’s community work includes the Los Angeles Urban League, the Watts Summer Games, City of L.A. Department of Parks and Recreation and the Boy Scouts of America. In 2017, he was given the Pioneer of African American Achievement by the Brotherhood Crusade of L.A. He has been the grand marshal at countless parades in Southern California.

In 2019, when Hill received a lifetime achievement award from the L.A. Press Club, I was asked to offer some opinion of his work for a piece written by Adam Rose. Noting that as far back as 1991, I had been ranking the best of L.A. sports media, I responded: “Through the years, Jim Hill was always the man in town as far as being here, there and everywhere. I spent a lot of hours with him in press boxes talking not just about the business but on how to treat people, things that should be reported and other things that are best kept private.”

When Kobe Bryant died in a helicopter crash in January of 2020, I noted in an L.A. Times media story that because of Hill’s connections in the sports and media community, it allowed him to bring trusted reporting.

“Jim Hill rushed into the KCBS-Channel 2 studio in suit and tie and had Magic Johnson on the phone while other local TV crews were scrambling to do fan-on-the-street reactions. That was impressive but not unexpected. Fast-moving stories like this can expose the strengths and weaknesses of newsgathering organizations. But amid the whirlwind, viewers can figure out which outlet may best serve their needs. For so many L.A. viewers, Jim Hill became the go-to voice. When Hill was able to give airtime to Johnson at midday Sunday, and for Johnson to admit that in a just world, it should be Bryant eulogizing him in a public setting instead of the other way around, was a chilling, bitter burst of reality for anyone who lived 25-plus years ago with the Johnson HIV announcement. Hill later had former Lakers great and team GM Jerry West, who orchestrated Bryant’s arrival in L.A. through the NBA draft and trade, and Lakers fan Jack Nicholson on the line for reaction.”

In a 2022 profile about him for the LA Downtown News, Hill said: “To me, trust is the most important quality you can have in any profession. If you trust them and they trust you, that goes a long way. Be truthful. Go about the job in the right way. That’s how you build trust in this industry.

“In recent years we lost Kobe. We lost Tommy Lasorda. These are men I admire and love. When you hear the news, you need to get your own thoughts together first. When you lose them, you lose a part of yourself. These things sometimes happen, and I have to report on those who I love and trust and admire.

“You know people are watching and they are watching to see how you handle yourself. You have such incredible emotions, and I will be the first to tell someone it is fine to cry. If you cry, those are tears of job because you have had them in your life. Don’t be phony. Let it happen naturally.

“It’s a great profession and it also carries with it a great deal of responsibility, and when you work with professionals in our city, everyone is good,” Hill said. “In the newsroom you have weather and breaking news and investigative work. But everyone loves sports. It brings people together.

“There is a place for everything, and everything has a place. Sports fits in both of those places.”

A 2021 story in the Los Angeles Times tracked down Hill to see what he thought it would be like having Super Bowl LV take place between Kansas City and Tampa Bay, the first staged after the COVID-19 pandemic and national protests in the aftermath of the George Floyd killing in Minnesota.

“One of the things I’m most proud of is how professional sports has stepped up to the plate big time in their beliefs about social injustice, how they realize what’s right,” said Hill. “They have taken all of this seriously.”

The story was under the headline: “KCBS legend Jim Hill is treating Super Bowl LV like any other Sunday. Well, almost”

There’s that word legend again. Straight to the day on Feb. 16, 2026 when KCBS-Channel 2 marked his 50th anniversary:

“I don’t know what to say, but the one thing that comes to mind right now, and you’ve heard me say it before, but Dr. King, he said, ‘Giving back to your fellow mankind is one of the most noble things that anyone can do,'” Hill said. “I’ve had, and still have, the noble position of giving back to our young people. I appreciate them and I appreciate everyone here.”

Who else wore No. 39 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

Sam Cunningham, USC football tailback (1970 to 1972):

Best known: The more complete account of Cunningham’s enduring legacy at USC — which started with him wearing No. 39 for the first time as a sophomore tailback — can be found in the 2006 book, “Turning Of The Tide: How One Game Changed the South.” Cunningham has authorship credit with former USC teammate John Papadakis, crafted by Don Yaeger, about the Sept. 10, 1970 meeting of John McKay’s Trojans with Bear Bryant’s Crimson Tide in Birmingham, Alabama. It was a calculated contest for Bryant, knowing USC had success with African-American stars and Heisman Trophy winners such as Mike Garrett and O.J. Simpson within the previous five seasons, and USC’s all-Black backfield of quarterback Jimmy Jones and running backs Cunningham and Clarence Davis would allow Crimson Tide fans to see what an integrated team could do. The fact USC came out with a 42-21 win, and Cunningham accounted for 135 rushing yards and two touchdowns (some newspapers mistakenly wrote he had 230 yards and three touchdowns) turned the spotlight on how this particular 6-foot-3, 226-pound fullback could impact a game.

Wearing No. 39 at Santa Barbara High, Cunningham was equally as effective as a fullback or a linebacker. At USC, teammate John Papadakis had the same talents to offer. So when Cunningham was made a fullback, Papadakis moved to defense. And when Papadakis tackled Cunningham in USC practices, it was a collision of respect and resilience.

“He learned to use his size and length to be graceful,” said Papadakis. “The No. 39 worked for him. It was a long number. I think Sam represented Santa Barbara as an idealic California coastal town, huddled along the mountains and beautiful shoreline. Santa Barbara has its own physical integrity that doesn’t exist in Monterrey or Carmel.”

It says Cunningham ran for 1,541 yards, averaging 4.7 yards per carry, and scored 19 touchdowns in his three seasons, but mostly, he launched himself for those stats. In the Trojans’ 42-17 win in the 1973 Rose Bowl over Ohio State before a record 106,000, Cunningham scored four second-half touchdowns that totaled five yards — all by leaping over the line of scrimmage and into the end zone, securing USC’s 12-0 finish and a national title. It’s how he got the nickname “Sam Bam.” The Rose Bowl put him into its Hall of Fame in 1992. USC put him into its Hall of Fame in 2001. College football put him into its Hall of Fame in 2010.

As documentations and Hollywood screenwriters alike have tried to recapture the 1970 USC-Alabama game in retelling its story, Cunningham told me in 2013 that the interviews never got tiring for him.

“Here’s a story that stayed dormant for some 30-something years. No one brought it up much before. Now … ” he said, his voice trailing off.

Cunningham says he doesn’t recall a lot of what happened that night. There is no disputing how it was a pivotal moment in the game’s history, but the dispute seem to be in some of the details.

In the 2024 book, “College Sports: A History,” writers Eric A. Moven and John R. Thelin addressed it in a chapter about how college football was part of desegregation.

“Much of the historical lore following the game has proven to be untrue,” they wrote. “Coach Bryant did not drag Sam Cunningham in front of his team and say, ‘Gentleman, this is a football player.’ Nor did the game convince Bryant that he needed to recruit Black athletes. He had already attempted to recruit African American football players to Alabama, and one, Wilbur Jackson, had signed with Bryant and played on the freshman team that year. The importance of the game was not convincing Bear Bryant to recruit Black athletes, as many have supposed. Instead, the value was in convincing a contingent of white Alabamans that discriminating against Black players harmed their beloved Crimson Tide.”

Jerry Claiborne, a Bryant assistant, had famously said, “Sam Cunningham did more to integrate Alabama in 60 minutes than Martin Luther King did in 20 years.”

In “College Sports: A History,” its chapter continues: “The unfair comparison between a college football player and the nation’s most revered civil rights leader falls short in many ways, but it did help explain that self-interest rather than social justice helped prepare southern football fans for desegregated football. The next year, when Wilbur Jackson stepped onto the field, he was joined by Mobile, Alabama native and community college transfer John Mitchell. These two football players and their teammates led the resurgence of Alabama football into the seventies that included standouts like Ozzie Newsome and Sylvester Croom (who went on to become the first Black football coach in the SEC when he accepted the post at Mississippi State in 2008).

“Bryant’s Black players spoke of their coach’s fairness, but the legendary coach had chosen to follow rather than lead in the area of athletic desegregation. … When Huntsville, Alabama native Condredge Holloway was being recruited by programs around the South, Bryant told the high schooler that the state of Alabama was not ready for a Black quarterback.” Holloway went to Tennessee and became the SEC’s first Black starting quarterback in 1972, two seasons after the USC-Alabama game.

It came out in 2010 that FBI director J. Edgar Hoover had a keen interest in Alabama’s move to segregate its football team, perhaps thinking that Bryant had violated some 1964 Civil Rights Act rules and it could be used to preserve the South’s desire to keep more Blacks off its roster.

Comedian Shane Gillis may have put it better in this clip from one of his acts:

In 2016, Cunningham was USC’s honorary caption when the Trojans opened the season against Alabama. That game was in Arlington, Tex., instead of Birmingham.

When Cunningham died at 71 at his home in Inglewood in 2021, one website said in its headline that he “symbolized and fueled a movement.” The New York Times obit headline included: “Fostered Integration on the Football Field,” and the story ended with this:

“I didn’t go into any game looking to change history, even though history has a tendency to be changed by things of that nature,” Cunningham told The Santa Barbara Independent this year. “I always tried to play to the best of my ability, and that’s what I did that evening. I was put in the right spot and got touched by the hand of God.”

Not well known: Sam Cunningham had his No. 34 retired at Santa Barbara High School in 2010, the same day the school also retired his younger brother Randall Cunningham’s No. 12.

Woody Strode, UCLA football end (1936 to 1939); Hollywood Bears football end (1940 to 1942); Los Angeles Rams end (1946):

Best known: His one season in the NFL didn’t come until he was 32 years old — 10 games, four catches, 37 yards. By then, Strode didn’t need the NFL to validate his life’s worth. It started at UCLA, wearing No. 34 in the same backfield as Jack Robinson and Kenny Washington, known as “The Gold Dust Gang.” He circumvented the NFL’s racial biases to join the Hollywood Bears of the Pacific Coast Professional Football League, then cut short when he was drafted by the Army at age 27. He played on the Army football team at March Field in Riverside, also unloading bombs in Guam and in the Marianas as part of his call to duty. It was only when the Rams moved from Cleveland to Los Angeles and the NFL conceded to being more racially diverse did Strode get his token shot, adding him to the team to help Kenny Washington also make the transition. After trying to make it work in the pro wrestling circuit, Strode set himself up as a career actor — cast as a slave in the 1956 “The Ten Commandments” as well as Ethopian king. He was the Ethopian gladiator Draba in the 1960 film “Spartacus,” opposite Kirk Douglas. He was also in the 1962 “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence,” and worked until 1995 in the western “The Quick and the Dead,” which came out a year after his death in Glendora at age 80. It is said that Sheriff Woody in the Disney movie “Toy Story” is named after Strode. UCLA inducted him into its Athletic Hall of Fame in 1992.

Not well remembered: Woodrow Wilson Woolwine Strode, born in L.A. and a graduate of Jefferson High, was also a world-class decathlete, setting UCLA records in the shot put and discus.

Milt Davis, UCLA football defensive back (1952 to 1953):

Best known: Born to parents of both African American/Native American ancestry on an Indian reservation in Oklahoma, Davis ended up moving to Southern California during the Depression and had to grow up at a Jewish Vista Del Mar orphanage. After graduating from L.A.’s Jefferson High School, he attended Los Angeles City College while working to pay for his tuition. He also ran track and was good enough at the quarter-mile to earn a partial scholarship to UCLA, recruited by head coach Red Sanders after seeing him play intramural flag football on campus. Davis’ bio for the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame inductee in 2024 notes that the Bruins’ football team was 16-3-1 during his junior and senior seasons when they made it to the 1954 Rose Bowl Game. Picked by Detroit in the 1954 NFL, he served in the U.S. Army, came back to pro ball and helped Baltimore to back-to-back NFL Championships in 1958 and 1959. In his rookie season, he recorded 10 interceptions and had seven more in his second season.

Not well remembered: When Davis retired from the NFL after four seasons and returned to UCLA to pursue a doctorate degree in education, he ended up teaching at John Marshall High in L.A. as well as serving a professor at L.A. City College. He also worked as a NFL scout for 36 years.

Mike Witt, California Angels pitcher (1981 to 1990):

Best known: A 6-foot-7 native of Fullerton, Witt went 14-0 at Anaheim’s Service High leading it to the CIF Southern Section 4A title in 1978. The Angels made him a fourth-round pick a month later. By age 20, three seasons later, Witt was making his debut. Witt’s 10 years in Anaheim mixing in a top-notch curveball with a fastball, resulted in a 107-107 record with 1,373 strike outs in 2,108 innings, two All-Star appearances and third place in the 1986 Cy Young voting (18-10, 2.84 ERA, 14 complete games in 34 starts with three shutouts and a 6.1 WAR) at age 25, a time when the Angels were within one strike of making the World Series.

Not well remembered: Witt’s largest brushes with MLB history came on the last day of the 1984 regular season and in one of the first days of the 1990 season. As the Angels finished up ’84 on Sunday, Sept. 30 in Arlington, Tex., Witt threw a 1-0 perfect game against the Rangers in an hour and 49 minutes, striking our 10. In the third game of the ’90 season at Angel Stadium, Witt came on in relief to pitch the final two innings and save a 1-0 no-hitter was started by Mark Langston against Seattle. Witt became a coach at Dana Hills High and Santa Margarita Catholic High School in Orange County.

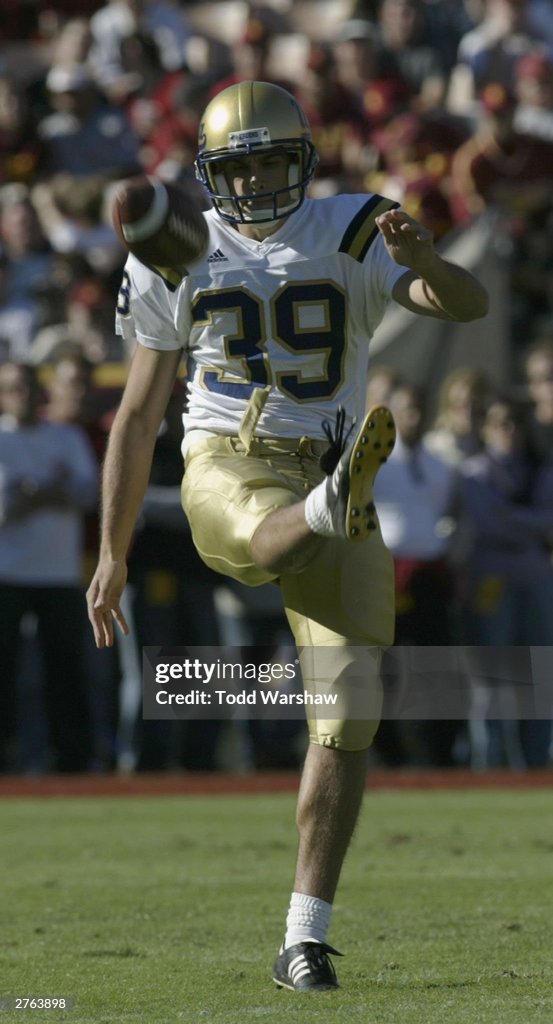

Chris Kluwe, UCLA football punter (2001 to 2004):

Best known: One of the best at his position in the Pac-10, Kluwe came to Westwood from Los Alamitos High. He was a finalist for the Ray Guy Award as the nation’s best punters and tied a Silicon Valley Bowl record with nine punts, three inside the 20-yard line, during the Bruins’ 17-9 loss in 2003 to Fresno State. The 6-foot-4, 215-pounder signed as a free agent with Seattle but his entire eight-year NFL career was with Minnesota. Kluwe connected on 623 punts for 27,683 yards (44.4 average) and 198 inside the 20. Already an outspoken advocate on many social issues, including gay rights and same-sex marriages, Kluwe believes his opinions led to his release from the Vikings in 2012 even though he held 14 team records.

Not well remembered: In addition to playing a progressive metal band, Kluwe wrote a book in 2013, “Beautifully Unique Sparkleponies,” a collection of essays he did for the website Deadspin. Kluwe was hired as the special teams coach at Huntington Beach’s Edison High in 2017, but was let go in 2025 after he was arrested during a peaceful protest at a city council meeting over a library plaque with political verbiage that supported President Donald Trump and the MAGA movement.

Petr Sykora, Mighty Ducks of Anaheim right wing (2002-03 to 2005-06): The Czech star ended the longest game in Ducks history — a five-OT victory in Game 1 of the Western Conference semifinals against Dallas in a game that went more than 140 minutes. He also scored the game-winner in a 1-0 triumph over Minnesota in two OTs in the Western Conference finals. The team advanced to its first Stanley Cup final against New Jersey, Sykora’s former team. During the 2004 NHL lockout, he went back to play for the Metallurg Magnitogorsk team of the Russian Superleague. Sykora had 64 goals and 67 assists in his 197 games during three seasons in Anaheim.

Dave Parker, California Angels DH (1991): The 2025 Baseball Hall of Fame inductee was able to wear No. 39 his entire 19-year career, which would have finished as an Angel in ’91 had they not decided to release him in September of that year. He then caught on with Toronto for 13 games. Parker came to the Angels at a bit of a cost — GM Mike Port traded young favorite Dante Bichette to Milwaukee for him in 1991 spring training. Bichette would be a four-time NL All Star in Colorado. Parker, a career .290 hitter with two batting titles, had started in a DH role with Oakland in 1988. His time with the Angels: A .232 average with 11 homers and 56 RBIs in 119 games.

Hoyt Wilhelm, California Angels relief pitcher (1969): The Hall of Famer knuckleball expert wore eight different numbers of his 21 seasons. He landed in Anaheim for 1969 after he had been picked in the expansion draft by Kansas City off the Chicago White Sox roster, then traded to California for Ed Kirkpatrick and Dennis Paepke. Wilhelm, at age 46, made it into 44 games in relief with a 5-7 mark and 2.47 ERA with 10 saves in 65-plus innings. The Angels traded him in the last month of the season to Atlanta in a deal that brought them outfielder Mickey Rivers.

John Montague, California Angels relief pitcher (1979 to 1980): In Game 1 of the 1979 ALCS at Baltimore, Nolan Ryan had struck out eight and gave up just one earned run in seven innings. But Montague was brought in. As the game went into the 10th inning tied at three, Montague gave up a single to Doug DeCinces. Al Bumbry was walked intentionally. John Lowenstein, hitting for Mark Belanger, hit a three-run homer to end it with two out.

Ryan Ting, USC football corner back (2003 to 2005): With twin brother Brandon (wearing No. 38), the Ting brothers were a thing, especially during their junior season playing in the national championship game against Texas at the Rose Bowl. Ryan Ting had two interceptions and 25 tackles as a junior (while Brandon had one pick and 12 tackles). The duo announced they would be skipping their senior seasons to concentrate on school. It was noted that the brother’s mom wore a jersey to games with No. 38 in the front and No. 39 on the back. “People come up to us and say she likes Brandon more because 38 is in the front,” said Ryan.

Dwight Howard, Los Angeles Lakers (2019-2020 and 2021-22): His first Lakers stop in 2012-13 saw him wear No. 12. He left. He came back seven seasons later, taking No. 39, as a backup on center on the team won the NBA title in the COVID bubble. He left. He came back again a season later, and got in 27 starts in 60 games at age 36, and then retired. He is the only Laker in franchise history to wear No. 39.

Why the Dodgers have retired No. 39:

Roy Campanella, Brooklyn Dodgers catcher (1948 to 1957):

He had a night to remember at the Los Angeles Coliseum on May 7, 1959, in front of more than 93,000 fans who struck a match to shine a light in his honor during a Dodgers-Yankees exhibition game.

The event was more than a year after a Jan. 28, 1958 car accident left him paralyzed, days before he was scheduled to leave for the Dodgers’ Vero Beach, Fla., spring training site.

His No. 39 was retired by the Dodgers in his honor in 1971 on the same day as Sandy Koufax’s No. 32 and Jackie Robinson’s No. 42 — the first three in franchise history to be taken out of circulation.

The three-time NL MVP, 11 time NL All Star (eight with the Dodgers, three in the Negro Leagues, where he also won a batting title in 1944 hitting .388) and 1955 World Series champ needed seven votes (1964 through 1969) to finally get enough support for a Baseball Hall of Fame selection.

The Dodgers had somehow allowed pitchers Ken Rowe (1963), Howie Reed (1964 to 1966) and Bob Lee (1967) to wear No. 39 after Campanella’s career ended. Lee, a Bellflower High product nicknamed “Moose,” made the AL All-Star team in 1965 with the Angels when he was 9-7 with a 1.92 ERA as a relief pitcher who recorded 23 saves in 69 games. The Dodgers got him in a trade and let him keep No. 39.

Anyone else worth nominating?

3 thoughts on “No. 39: Jim Hill”