This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 46:

= Burt Hooten: Los Angeles Dodgers

= Todd Christensen: Los Angeles Raiders

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 46:

= Don Aase: California Angels

= Dan Petry: California Angels

The most interesting story for No. 46:

Juan Marichal, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1975)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Dodger Stadium

Juan Marichal’s matriarchal Hall of Fame plaque in Cooperstown seems to have one dandy of a typo.

After all he accomplished for the San Francisco Giants in a 16-year MLB life, the last line of his career ledger reads: “Los Angeles N.L., 1975”

It’s because that actually happened.

What a kicker to a spiteful spit take.

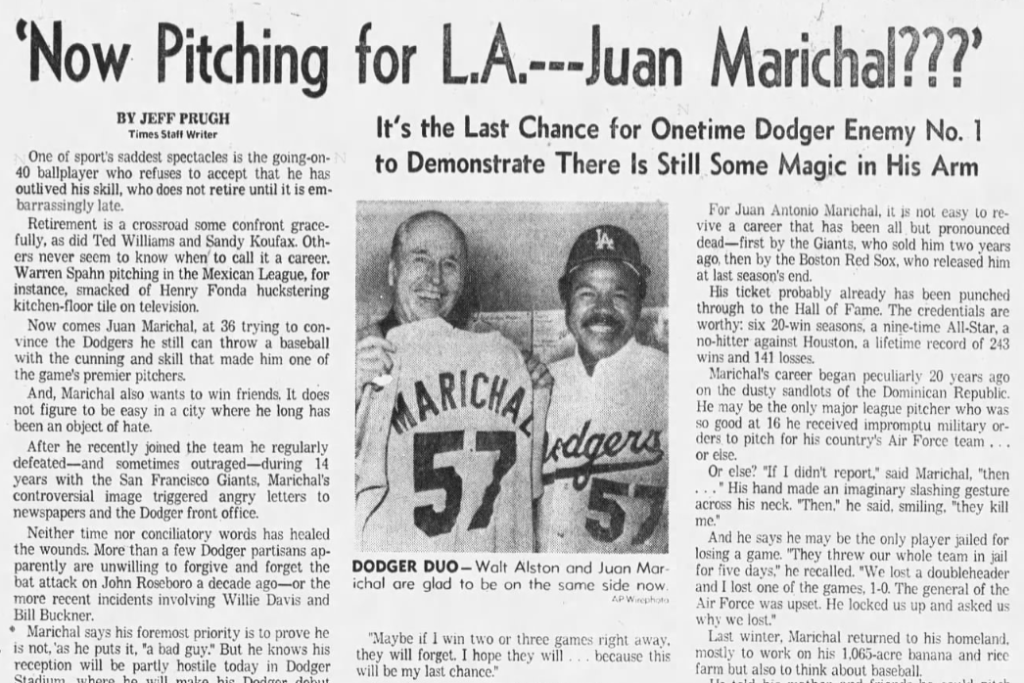

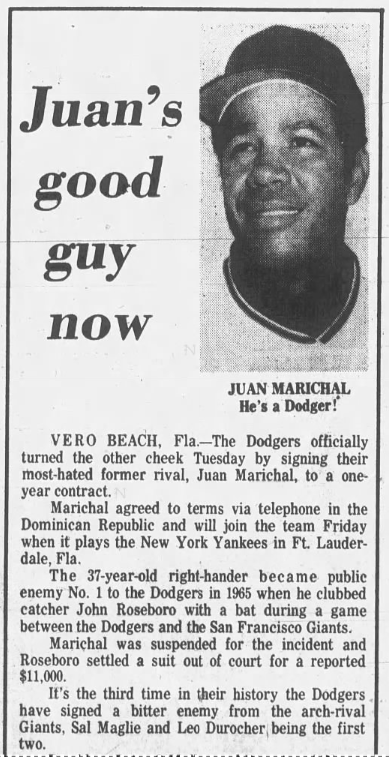

When The Associated Press posted a story prior to the 1975 season, explaining how the nastiest of the rival Giants had accepted a one-year, $60,000 contract with the intent of actually trying to help the Dodgers win games, the lede read: “Baseball, like politics, apparently makes strange bedfellows.”

The Los Angeles Times’ Jim Murray launched into a column a week later: “There’s a new game in town today. It begins, ‘Juan Marichal, playing for the Dodgers, is like …’ And you supply your own punch line.” Murray’s suggestions: “King Faisal at a bar mitzvah … like Brezhnev at a White House prayer meeting … In the view of most Dodger fans, Juan Marichal belongs in the Nuremberg trials, not in Dodger Blue.”

At the Long Beach Press-Telegram, columnist Bud Tucker lamented: “It wouldn’t matter if the guy could win 25 games. Adolph Hitler is Adolph Hitler and Juan Marichal is Juan Marichal.”

A month earlier, Herald-Examiner columnist Melvin Durslag had written: “If all the Dodger hitters that Marichal has put in the dirt were laid end-to-end, they would stretch from Chavez Ravine to Santo Domingo.”

Marichal’s decades-long existence as L.A.’s Public Enemy No. 1 all goes back to one of the most abhorrent incidents in the Dodgers-Giants historic and on-going rivalry.

A now hard-to-find book published in 1964 about the history of this series by Lee Allen called “The Giants & The Dodgers: The Fabulous Story of Baseball’s Fiercest Feud” a cover illustration shows a Brooklyn Bum going after a Giant with a baseball bat. Marichal flipped that script, and was forever linked with John Roseboro, the Dodgers’ catcher, during a game at Candlestick Park in 1965. There is far more context and social significance to what happened that day.

Somehow, Marichal and Roseboro turned it into a story of forgiveness, friendship and the foundation of what sports can do to heal all wounds.

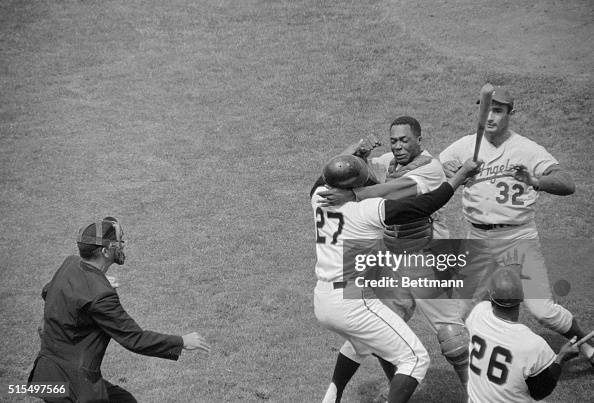

A pennant-heated August 22, 1965 game in San Francisco devolved into an assault with a deadly weapon. Books have been written about it. Plays have been scripted about it. Documentaries are in the works.

The Los Angeles audience, still reeling from the Watts Riots, got to see it live on KTTV-Channel 11 — one of the few televised games of the season.

Marichal ended up with a nine-day suspension and a record-setting $1,750 fine for “nearly committing baseball’s first homicide” (as Murray wrote) — using his bat to crack the skull of Roseboro after words and brush-back pitches escalated to outrage.

Outraged himself, Dodgers outfielder Ron Fairly, who earlier in the game had been thrown at by Marichal, said he thought the punishment should have been reversed to a $9 fine and a 1,750-day suspension.

Roseboro, who had a second-inning RBI single against Marichal to put the Dodgers up 2-0, needed 14 stitches to cap off the 14-minute bench-clearing brawl. He missed two games, and would file a suit against Marichal for $110,000 in damages.

The case was eventually settled in February of 1970 with Roseboro receiving $7,500.

Marichal, who once sent Dodgers star Willie Davis to the hospital after hitting him with a pitch and also had another near-fight with Bill Buckner for a brush-back incident, couldn’t run from his history. But his suspension made a difference in how the National League pennant was resolved. He missed two starts. The Dodgers won the ’65 pennant by two games, then defeated the Minnesota Twins in the World Series.

The title didn’t tarnish the terrible event. Not even years later.

Coming off a trip to the 1974 World Series, the ’75 Dodgers saw some problematic holes in their starting rotation.

But why go down the soul-crushing path of desperation and even consider adding Marichal? Because history tells it happens quite enough when a team is looking for any chance to win.

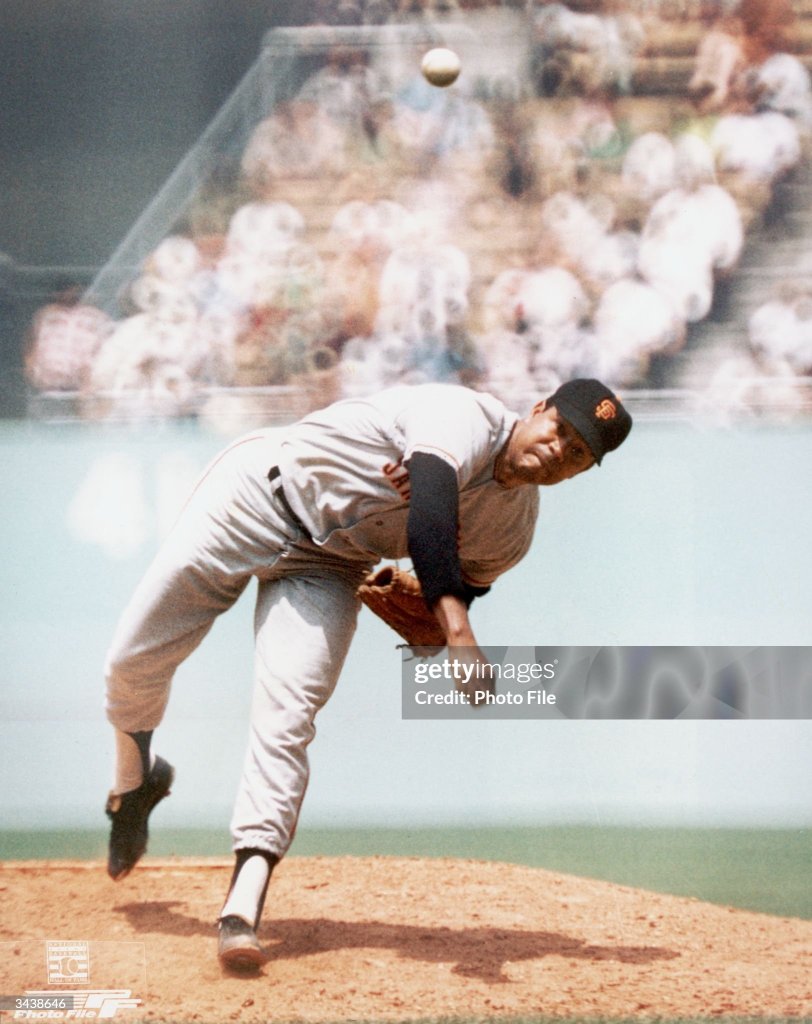

Marichal should have already built a Hall of Fame resume just on his 14 seasons with the Giants: 458 starts, 52 shutouts among 244 complete games, 10 All Star games, six 20-win seasons (leading the league in ’63 and ’68), three times going 300-plus innings. The quirk is Marichal never won a Cy Young Award because of the voting circumstances and competition of the day. But during the 1960s, Marichal was far-and-away the game’s most productive right-handed pitcher with 191 wins — and 197 complete games came with it. He also pitched and won what many consider the greatest single game in MLB history — as a 22-year-old, outlasting 42-year-old Warren Spahn, during a 16-inning complete-game, 1-0 shutout in 1963.

One-time Dodgers Hall of Fame executive Branch Rickey once said about Marichal: “No pitcher has made such magnificent use of his God-given equipment.”

Marichal had a career record of 21-4 at Dodger Stadium. He was 37-18 mark with 10 shutouts against the Dodgers over the years.

But by 1975, he had, for all intents and purposes, figured he was done. His back wasn’t cooperating.

(A personal note: On May 25, 1971, I saw Marichal throw a complete-game 9-1 win at Dodger Stadium against Bill Singer. The caper was seeing Marichal hit a three-run home run in the sixth inning down the left-field line that broke open a 1-0 game.)

Following the Giants’ 1971 NL West title by outlasting the Dodgers, where Marichal was 18-11 with a 2.94 ERA and his final All Star appearance and eighth in the NL Cy Young voting, he was injury plagued and rather ineffective during the ’72 and ’73 seasons — a combined 17-36 with an ERA near 3.80. The Giants unceremoniously sold his contract to the Boston Red Sox. Although he posted a 5-1 record in his brief American League career, his 4.89 ERA in only 11 appearances covered just 57 innings. The Red Sox released him in October of ’74.

He went home to his farm in the Dominican Republic and rested.

When spring of ’75 rolled around, the Oakland Athletics appeared to be most interested in bring Marichal back for a Bay Area victory lap. They needed to replace free-agent defector Catfish Hunter.

When that didn’t happen, the idea that Marichal might actually wear Dodger blue apparently came from Dodgers senior vice president Al Campanis. He sent out some of the Dodgers’ Dominican players to check in on Marichal.

“I hadn’t expected to hear from the Dodgers of all teams because it was my belief they were heavy on pitching and they wouldn’t call on me anyway because of things that happened in the past,” Marichal told the Long Beach Independent.

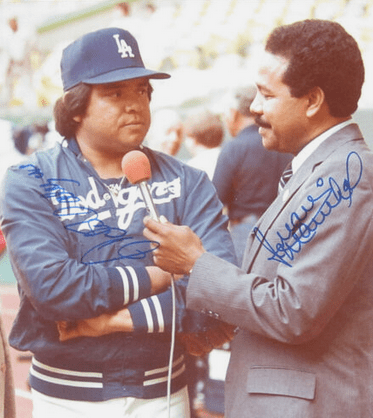

“My friend, Manny Mota, was still in the Dominican when the Dodgers contacted me and he strongly advised me to try to pitch again. I wasn’t sure, but since Manny was with the Dodgers, I decided to give it another try. If it hadn’t been for Manny, I doubt if I would have returned to baseball.”

Campanis danced around his part in all that when asked about it.

“Listen, nobody hated Juan Marichal more than I did,” Campanis said at the time of the signing. “But there are times when things change, when your affections replace any ill feelings … All it cost us what an invitation and an offer of a contract. It really didn’t cost us anything.”

Hate can be a strong word to use here. But it seemed almost appropriate.

Vin Scully said of the whole transaction that occurred on March 12, ’75: “I’m glad they didn’t do this on the first of April … Nobody would have believed it.”

The NL champion Dodgers’ four-man starting rotation already had Andy Messersmith, Don Sutton and Doug Rau. There was veteran Al Downing or 21-year-old Rick Rhoden available to fill it out.

This was when it was doubtful that Tommy John would ever come back from the landmark elbow surgery just prior to the ’74 World Series.

“If I don’t have any problems with my back, I can win for this team,” Marichal told the Sporting News at the time.

“Everyone asks me, ‘How’s your arm?’ It’s not my arm. It’s my back that’s been the problem. If I’m not OK and can’t pitch I’ll tell them. I signed a contract with that agreement.”

And now — the Dodgers had his back?

In Vero Beach, Fla., Dodgers equipment manager Nobe Kawano couldn’t give Marichal his familiar No. 27 because Willie Crawford was wearing it. Kawano decided to have Marichal try on the No. 57 because the thought there was a visual similarity in it to 27.

By the end of spring, Marichal was one of 11 pitchers who went back to L.A. with the team. His number was upgraded to No. 46 — the lower the number, maybe it seemed as if he wasn’t such a longshot.

During the final game of the annual Freeway Series exhibition against the Angels, about 18,000 at Dodger Stadium saw Marichal go six innings, give up three runs on four walks and seven hits, and retired 10 of the last 11 he faced.

When he walked off the field at the end of his sixth inning, it was noted that Marichal received an ovation of sorts.

“I was wondering what the fans would do,” Marichal said. “It was much better than when I was with the Giants. I really like that.”

Still, this would be a test of many people’s patience.

The Dodgers’ rationale was that if despised former Giants like Leo Durocher or Preacher Rowe or Sal “The Barber” Maglie could come over to the Dodgers’ side at some point in their careers, why not Marichal?

If Dodgers once traded Jackie Robinson to the Giants (he retired instead of accepting it) and Duke Snider could hit the last of his 407 home runs in a San Francisco uniform, why couldn’t Marichal pitch his final innings with the team he once tormented?

Because …

Well …

Just because.

“I’ll just go back to my farm and listen to games on the radio,” Marichal said when asked what might happen if this didn’t work out, alluding to his 1,065-acre ranch that produced crops of rice and bananas. “I’m going to be happy on my farm. I was before I came here.”

In Los Angeles, resentment against him grew by the bushels.

When the ’75 season began, Dodgers manager Walter Alston waited to give Marichal his first start in the fifth game, April 12 at Houston. Marichal got through three scoreless innings against the Astros and had a 2-0 lead when he gave up a two-run homer to Cliff Johnson. After Enos Cabel laced a double over the third-base bag to score two, giving Houston a 5-2 lead, Alston came to the mound, took Marichal out, and brought in Jim Brewer.

An estimated two million fans in the Dominican Republic listened to Marichal’s comeback during a special radio broadcast.

“I tried to do so good but everything went wrong,” Marichal told the Los Angeles Times. “I know I’m not in shape yet. My legs are sometimes still sore from running. I really need two more weeks to be in top shape. And if I don’t …”

He stopped for a long silence.

“Then, there’s no excuse,” he finished.

“I think you have to give him a little time,” said Dodgers catcher Joe Ferguson, who said during spring he though the Marichal signing was a publicity stunt but now seemed to be changing his tone. “He’s not the Juan Marichal of five years ago.”

The official end to the Marichal reboot actually came quicker than anticipated.

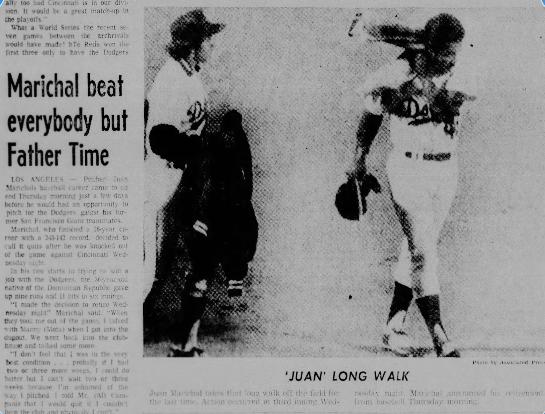

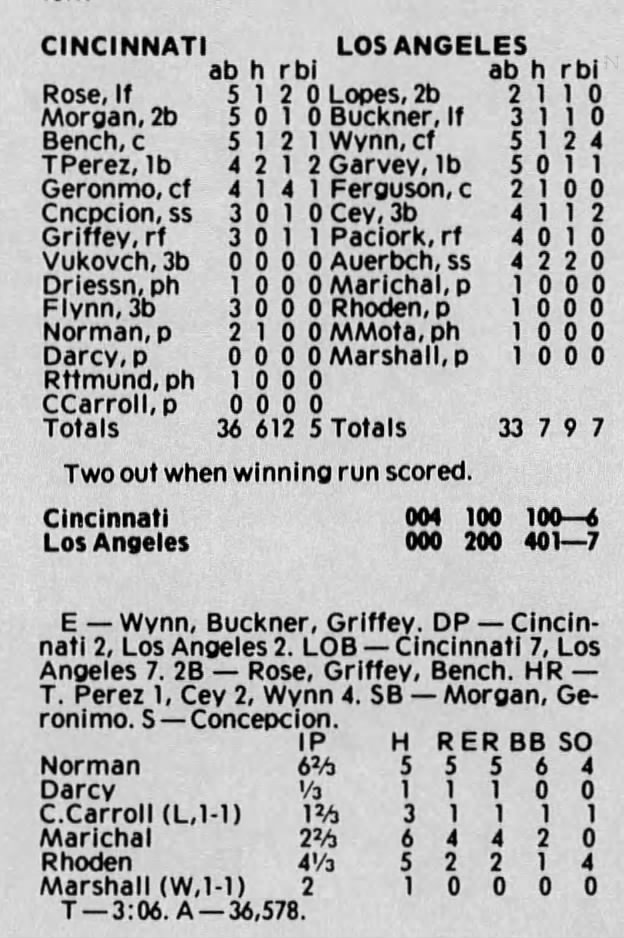

On Wednesday night April 16 at Dodger Stadium before some 36,000 fans, Marichal faced the robust lineup of the Cincinnati Reds. He got out of the first inning clean against Pete Rose, Joe Morgan and Johnny Bench. In the second inning, Marichal left the Reds with the bases loaded. In the third, Rose doubled and scored on Bench’s single to center. Tony Perez hit a two-run homer. Cesar Geronimo singled to center. Dave Concepcion singled to right.

Alston came out. Marichal’s game was done.

Even though the Dodgers rallied from a 4-0 deficit to win 7-6 in the bottom of the ninth — a seventh-inning grand slam by Jimmy Wynn to tie it and a walk-off single by Steve Garvey to win it — this was a no-win situation for Marichal. His final pitching line: 2 1/3 innings, six hits, two walks, four earned runs and no strikeouts.

After the game, the Dodgers’ Mota took Marichal to Tonita’s restaurant in L.A., a popular hangout for Latin players. They were joined by the Reds’ Perez, Geronimo and Concepcion — the trio who had the last three hits off Marichal to effectively end the comeback idea.

Marichal waited until the next day to inform Alston and the Dodgers that he was going out on his own terms. There was no pride in posting an 0-1 record and 13.50 ERA.

“I think retiring is the best thing I can do,” he said. “Don’t feel sorry for me.”

Alston added: “Marichal showed me a lot. It takes a man to do what he did. A lot of guys would make excuses, but Juan did not. Really, he didn’t pitch that badly.”

The experiment lasted just about one month, but some some it felt like an eternity of betrayal. If only Marichal had been able to hang on for one more game, he would have faced the Giants.

“It would look even worse if something happened against the Giants — the one team I wanted to beat was San Francisco,” he said.

He couldn’t even give Dodgers’ fans that satisfaction.

The night before Marichal’s last game, Dodgers future Hall of Fame starter Don Sutton threw a one-hitter to beat Cincinnati, 2-1. Sutton took a no-hitter into the seventh inning until Bench hit a home run.

Sutton admitted afterward that having Marichal as a teammate was pretty swell.

“I used to hate him like everyone else on our club, but since he’s been here, he’s been a good friend,” Sutton, who shutout Houston in previous start, told the Associated Press. “We talked quite a bit about pitching. We’re similar. We throw breaking balls for strikes and spot the fastball.”

Campanis offered as damage control about the Marichal signing: “The cost is only incidental. We feel we were right in taking a chance on him. When you are looking for a starting pitcher, you always try to obtain as many candidates as possible. Juan was a real gentleman about what has happened … I made a mistake — and I’ll be the first to admit it.”

(Campanis, of course, made an even bigger mistake in an 1987 appearance on ABC’s “Nightline.” But that’s for another soliloquy.)

Garvey said of Marichal: “It takes a lot of courage to do what he did. Probably more than anything else he’s done.” Added Ferguson: “He is one helluva nice guy. I hated to see it happen this way. It became a matter of pride to him, and he didn’t want to push it any more. … to force the issue. I only wish I had the privilege of catching in his prime.”

Later that summer, Marichal would be back at Dodger Stadium. In a Giants’ uniform. For Old Timers’ Day.

Yeah, just like old times.

The aftermath

What did Roseboro think about all this Marichal-Dodgers news?

Having retired as a player after the 1970 season, Roseboro actually held a press conference to welcome Marichal to the team. His words didn’t resonate much.

Roseboro said again he was been pulling for Marichal to do well. He went on a local sports talk show with Bud Furillo and asked fans to forgive and forget.

“No resentment whatsoever,” said Roseboro, whose last time in uniform was as a coach for the California Angels. He was now was selling insurance in Glendale as well as selling cars in Pomona.

Prior to Marichal’s retirement announcement, Roseboro also made it clear:

“I’d really like to see the dude win about 15 games for the Dodgers. That would sure ease a lot of problems out there. I think the first year, you want to retaliate, but after that, you say it’s just another baseball fight and you forget about it.

“I look at it as another fella who’s getting a chance to play a little longer and any time a guy 36 or 37 years old gets another chance to ply his trade, you root for him. I think people won’t forgive that he beat us regularly, but the fight thing — I think that’s something that happens every day in baseball. They can’t get down on him because he threw close to the hitters. He wouldn’t be a great pitcher if he didn’t. That’s part of the game.”

If more Marichal backlash still lingered, it was most evident with Baseball Hall of Fame voters.

In 1981, Marichal’s first year of eligibility, he got only 58.1 percent of the vote. Contemporary pitcher Bob Gibson got in on his first try. Marichal should have been as well based on everything on the back of his baseball card.

“I can only assume they’re still punishing the guy for hitting John Roseboro on the head with a bat,” Tom Barnidge wrote in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

In 1982, Marichal just missed with 73.5 percent, seven votes shy of the 312 needed. Contemporaries Hank Aaron and Frank Robinson were voted in.

Steve Daley wrote in the Chicago Tribune: “Certain writers in Southern California have never forgiven Marichal for swatting John Roseboro with a bat some years ago; they leave him off the ballot for that reason alone.”

Marichal needed help. He needed Roseboro. Even if they stood on the same field together at the 1975 Old-Timers’ Game, they hadn’t talked in 18 years.

In the “Battle of Candlestick” Wikipedia entry — a more polite way to refer to something most call the “Marichal-Roseboro Brawl” — it noted that Marichal did not pitch against the Dodgers after that incident until April of 1966 in spring training in Florida. Roseboro hit a three-run homer off Marichal in their first encounter — and declined to take a photograph with Marichal shaking hands even as the two team’s GMs pushed for it to happen.

As important as it was for Marichal to be the first Dominican inducted into Cooperstown, Roseboro had to somehow become a deal broker and peacemaker.

In the summer of ’82, Marichal was invited to return to Dodger Stadium to be celebrated as part of the team’s annual Old Timers’ Game. This time, he did so wearing a Dodgers’ uniform — with the old No. 27 he wore for the Giants, and not with the Dodgers.

Roseboro showed up, posed for photos with Marichal, and it made news.

As another gesture of goodwill, Roseboro and his family accepted an invitation from Marichal years later to fly to the Dominican Republic for a charity golf tournament. Roseboro was impressed with the reception they got.

“It doesn’t surprise me that he would do something like that,” said John Werhas, a former Dodger infield who became a church pastor. “John Roseboro was probably as nice a human being as you’d ever meet.”

In late ’82, the Cooperstown ballots went out again, and Marichal finally pushed over the threshold with 83.7 percent. He was part of the Hall’s Class of ’83 along with Alston, who got voted in by the veteran’s committee.

In Marichal’s 2013 SABR bio, writer Jan Finkel went over how “conventional thinking indicates that a group of voters chose to punish him for the Roseboro incident. However, there is some reason to believe that Marichal was forgiven fairly soon after.” He noted a June 10, 1966 Time magazine story that called him “The Dandy Dominican.” The authors didn’t dwell so much on the Roseboro incident.

Roseboro told the L.A. Times in 1990: “There were no hard feelings on my part, and I thought if that was made public, people would believe that this was really over with. I actually visited him in the Dominican. The next year, he was in the Hall of Fame. Hey, over the years, you learn to forget things.”

In a 2009 interview for the MLB Network with Bob Costas, Marichal recounted the 1965 incident with more details on what led to the bat-swinging incident.

The Dodgers and Giants had worked their way to the final Sunday series finale with tensions high since a previous game in this four-game series.

Marichal, who in June threw two complete-game wins over Don Drysdale, once at Dodger Stadium and again at Candlestick Park, started off this one throwing high and inside to leadoff man Maury Wills. Marichal told Costas he was just trying to pitch him up and in to make it more difficult for him to bunt. Wills ended up laying down a bunt single. Later that inning, Fairly took a dive at the plate on an inside pitch by Marichal. He then drove in Wills with a double.

With one out in the bottom of the third as Marichal came to the plate for his first at-bat, he figured Koufax would want to retaliate by brushing him back. Marichal said he learned later that Koufax was told by Alston to hit him, but Koufax wasn’t going to do that. Roseboro knew that, and didn’t want Koufax thrown out of the game. This was already a rare head-to-head matchup of the two aces — they purposely only faced each other three times ever in a Dodgers-Giants rivalry game.

Marichal said Roseboro took it upon himself to drop a pitch from Koufax during that at bat, then he could throw the ball back to Koufax just past Marichal’s right ear to get the message across. That’s what started the war of words — and Marichal’s uncharacteristic reaction with the bat.

When Roseboro died in 2002, the headline in the L.A. Times showed that history couldn’t forget: “John Roseboro, 69, Dodgers All Star Catcher Gained Notoriety Following Melee in 1965.”

Roseboro, a four-time NL All Star and two-time Gold Glove winner who caught two of Sandy Koufax’s four no-hitters, said as much about it all in his 1978 autobiography, “Glory Days With the Dodgers and Other Days With Others“:

“The thing I’m remembered best for is the Juan Marichal incident. It’s too bad, because a ballplayer would like to be remembered for something better than a bloody brawl, but that’s what everyone always remembers, even those who weren’t there or who weren’t even following baseball back in 1965.”

Marichal also told Costas in that 2009 interview: “People ask me: Why did you end up with the Dodgers? Let me tell you the truth — I think the only reasons I signed with the Dodgers was because I wanted to people to know I wasn’t the type of person that would hurt someone over the head with a bat.”

Gwen Knapp wrote in the San Francisco Chronicle in 2005, on the 40th anniversary of the incident:

For both Marichal and Roseboro, the incident never really ended. That day … defined them in caricature, Marichal as violent perpetrator and Roseboro as victim. They were neither. But famous photographs from the brawl, showing Marichal with his bat poised to strike the catcher, created an indelible image. The pictures appeared in Life magazine and can still be purchased as baseball memorabilia.

In May of 2011, a stage play called “Juan and John” that had debuted in New York two years earlier made its way to the Kurt Douglas Theater in Culver City.

Roger Guenveur Smith wrote and starred in the one-man play.

This was just a month after the Dodgers’ opening day was marred by Dodgers-Giants related violence — Bryan Stow, a 41-year-old Giants fan, was assaulted by two Dodgers fans in the parking lot after the game and suffered serious head injuries.

Smith, in a lead-up to his play, recalled how he felt the day the Dodgers signed Marichal in 1975.

“It turned me off so much,” he said. “I couldn’t believe the Dodgers would betray history, that they would allow Juan Marichal to wear the hallowed Dodger blue.”

Smith started the play by taking out a lighter and burning a Marichal baseball card. That’s what Smith said he actually did as a 6 year old growing up in the Leimert Park/Crenshaw district of L.A. when he was watching that 1965 game on TV.

“Burn, baby, burn,” young Smith said as he watched the Marichal card disintegrate, repeating a mantra he had been hearing in the news at that when race riots in the nearby neighborhood of Watts had been quelled less than a week earlier.

“In playing Juan Marichal and John Roseboro, I have to invest in both men, for better or worse,” said Smith.

Roseboro’s widow, Barbara, attended the L.A. performance. She had said in a San Francisco Chronicle story that her husband was often approached about the incident, and he took ownership of it.

“He would always accept his responsibility,” she said. “He’d say: ‘I provoked it. I threw that ball too close to Juan’s ear.’”

Marichal and his family, along with Morgan Fouch Roseboro, John’s daughter, attended a special performance of “Juan and John” in New York, and Marichal admitted afterward: “I don’t cry too often, but Roger, you made me cry tonight.”

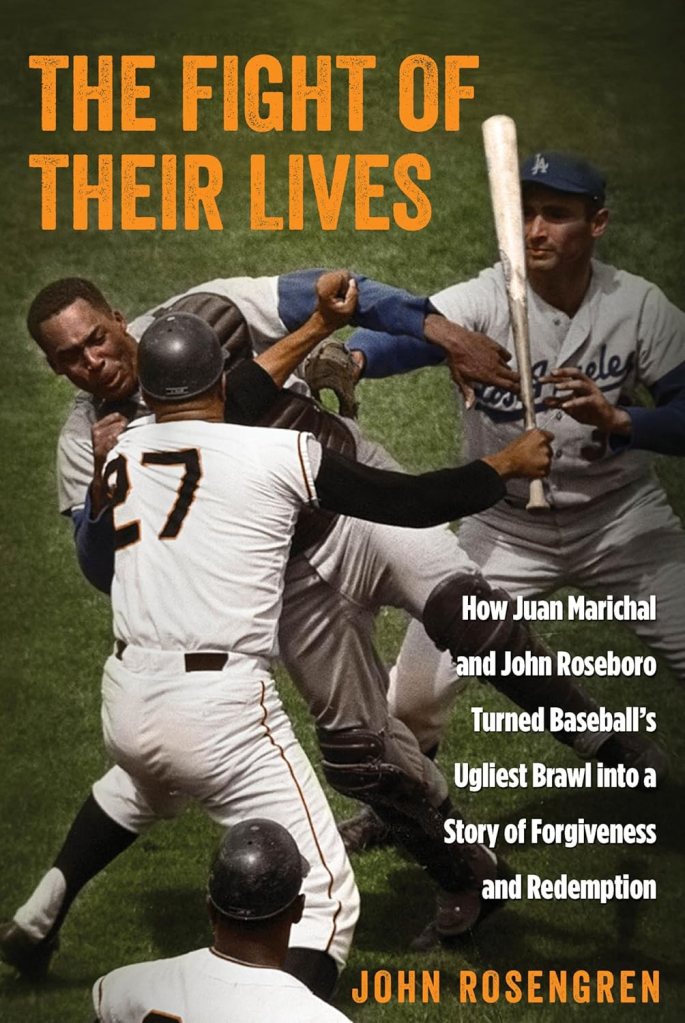

In a 2014 book written by John Rosengren called, “The Fight Of Their Lives: How Juan Marichal and John Roseboro Turned Baseball’s Ugliest Brawl Into a Story of Forgiveness and Redemption,” whose cover displayed the most cringe-worthy photograph, the author made a case that this whole thing was just years of pent-up animosity between the rivals, going back to New York and Brooklyn. Marichal was also consumed with anxiety about an on-going civil war in his native Dominican Republic that affected family members. The Watts Riots that had just happened in Los Angeles had the Dodgers’ players, especially Roseboro, on edge.

It was not just “another Latin player with a fiery temper who went out of control” and took it out on a Black man. It wasn’t about machismo.

Rosengren wrote: “When the Dodgers traveled to San Francisco for another series between the bitter rivals, it wasn’t simply two teams contending for the pennant. Larger, darker forces worked their influence on the stage of America’s game.”

When Roseboro died at age 69 in 2002, Marichal was an honorary pallbearer. He also spoke at the funeral: “I wish he could have been my catcher.”

That’s how Marichal ended his eulogy after a long pause to gather himself.

That’s also the quote Rosengren used to end his book.

In the play “Juan and John,” Smith repeats Marichal’s words as well.

Marichal was asked if, in fact, that was what he had said.

“Yes, I did,” he said. He paused for a moment and his eyes twinkled. “I might have won a few more games.”

Koufax also spoke at Roseboro’s funeral. At one point he turned to Marichal to say, “You would have loved pitching to John Roseboro.”

Who else wore No. 46 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

Burt Hooten, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1975 to 1984):

When the Dodgers’ Marichal experiment ended, Hooten happily became a Plan B. And also donned No. 46.

Hooten was traded by the Chicago Cubs about two weeks after Marichal’s retirement in exchange for young pitchers Eddie Solomon and Geoff Zahn. Hooten posted an 18-7 season for the Dodgers in 31 starts with 12 complete games and a 2.82 ERA, after he started the season 0-2 in three games for the Cubs.

How did he get the nickname “Happy.” Just look at his sad face.

In 1978, Hooten was second in the Cy Young voting to Gaylord Perry after going 19-10 with a 2.71 ERA. His one All-Star game came in 1981, the year the Dodgers won the World Series over the Yankees, and he was the NLCS MVP against Montreal allowing no runs in 14 2/3 innings. In 33 postseason innings that year, he allowed just three earned runs and went 4-1. And he won the clinching game of the World Series. In his career, Hooten won 112 of his 151 games with the Dodgers.

Kevin Gross, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1991 to 1994):

The Downey native out of Oxnard College threw the 18th no-hitter in Dodgers history on Aug. 17, 1992 against the rival Giants at Dodger Stadium, retiring 19 in a row at one stretch. That increased his record to just 6-12 for the season, and he would go 40-44 in four seasons for the Dodgers (the first, in ’91, wearing No. 45). He finished his career with the Angels in 1997 wearing No. 44.

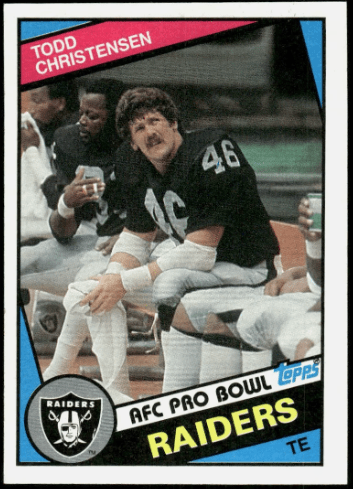

Todd Christensen, Los Angeles Raiders tight end (1982 to 1988):

A running back out of BYU wearing No. 41 when he started with the New York Giants in 1979, a year after Dallas tried to convert him into a tight end, Christensen ended up in Oakland. He took No. 46, agreed to finally become a tight end after three seasons in ’80 and ended up going to the Pro Bowl in ’83 through ’87, five seasons in a row. He led the league with 92 catches in 1983 and 95 in ’86. He also led the league in ’83 with 1,247 yards and 12 touchdowns. After his football career ended, he set an age group record in the Masters Track and Field circiut participating in the heptathlon. In 1990 during the MLB lockout, he also tried out for the Oakland A’s.

Have you heard this story:

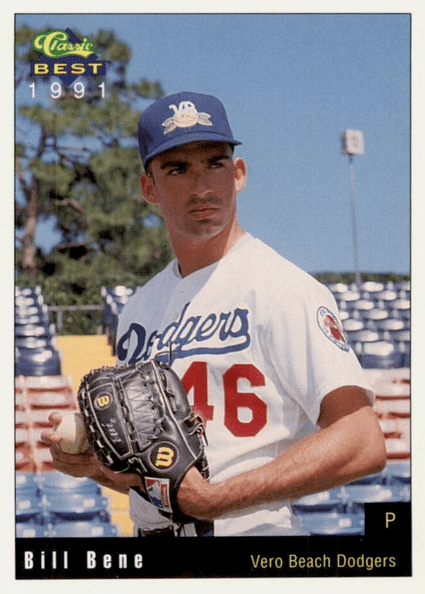

Bill Bene, Los Angeles Dodgers/Anaheim Angels minor league pitcher (1988 to 1997):

The Long Beach native was the Dodgers’ first round draft pick, No. 5 overall, out of Cal State L.A. in the 1988 June Amateur Draft. A 6-foot-4, 205-pound right hander was already a bit of a wild card pick.

A month before the draft, the 20-year-old Bene had a 5-3 record with 41 strike outs and 43 walks to go with a 6.86 ERA and 13 wild pitches. “You never know what will happen when he pitches,” said John Herbold, Cal State L.A.’s coach. “He might throw a no-hitter or he might walk the whole park.” He was an outfielder at Long Beach Jordan High and hadn’t pitched since Little League when a scout suggested he try pitching. He got up to 95 mph on the radar gun.

“It was a gamble, and I know if he doesn’t make it, a lot of people are going to take some heat,” Dodgers scouting director Ben Wade told The Times at the close of 1989. “But look at all he’s overcome, he’ll be fine.”

Bene would make it to Triple-A Albuquerque in 1994 as a 26-year-old. The Angels gave him a shot in 1997 with Triple-A Vancouver and Double-A Midland, but he was a combined 0-4 with an ERA of about 7.00. He never saw the MLB mound. After nine seasons in the minors, he was done. But he wasn’t finished making headlines.

Bene was sentenced to six months in prison in 2012 and ordered to pay more than $100,000 for selling illegal karaoke juke boxes between 2006 and 2010, as well as failing to report the $600,000 to the IRS. The crime was illegally copying and selling karaoke songs on hard drives with about 122,000 titles, said prosecutors.

We also have:

Craig Kimbrel, Los Angeles Dodgers relief pitcher (2022)

Don Aase, California Angels pitcher (1978 to 1984) Also wore No. 22 for the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1990.

Dan Petry, California Angels pitcher (1988 to 1989)

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 46: Juan Marichal (with John Roseboro)”