This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 35:

= Sidney Wicks, UCLA basketball

= Bob Welch, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Cody Bellinger, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Jean-Sebastien Giguere, Anaheim Mighty Ducks

= Christian Okoye, Azusa Pacific College football

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 35:

= Tank Younger, Los Angeles Rams

= Loy Vaught, Los Angeles Clippers

= Rudy LaRusso, Los Angeles Lakers

= Ron Settles, Long Beach State football

The most interesting story for No. 35:

Petros Papadakis, USC football tailback (1996 to 2000)

Southern California map pinpoints:

San Pedro, Palos Verdes, Hollywood, Los Angeles (Coliseum, Sports Arena)

Any sort of perfunctory profile of Petros Papadakis becomes the proverbial Sisyphean pursuit. Hopefully we don’t have to Greek-splain too much here.

Sisyphus, the first king of Ephyra, found his eternal fate in Hades rolling a huge boulder endlessly up a hill, only to see it come back down at him. Every time he made progress and got on a roll, it reversed on him like a Looney Tunes cartoon. The whole thing seemed so Kafkaesque that French philosopher Albert Camus, writing “The Myth of Sisyphus” in 1942, elevated him to some absurd hero status in Greek mythology.

Something that Papadakis might find relatable.

When Papadakis gets on his own a roll, cutting it up on KLAC-AM (570)’s afternoon sports-talk drive-time “Petros and Money Show,” there is far less sports and much more drive to just being a voice for “la raza.” It’s a focus on a feeling of being in “la ciudad” with Papadakis, as familiar as he is bombastic, just the person in the passenger seat making observational conversation to it real.

He is part of USC football legacy, a linage of Cardinal and Gold athletes whose performance has been documented in Los Angeles’ grand Coliseum. Papadakis’ work ethic formed at his family’s famously iconic San Pedro Taverna, as he went from dishwasher to waiter to spending all his earnings for the night back on his guests to make sure they went home happy.

Maybe Papadakis became an accidental broadcaster, but it’s a career that likely defines him as much if not more than anything else. Once a Trojan workhorse in the USC backfield, he is the sometimes-hoarse former Trojan on the dashboard radio. A Red Bull in a china shop of hot topics. The connoisseurs of SoCal sports who enjoy conquering as much as consuming any kind of history lesson are better for it.

Back to the profile: Papadakis has provided quips along the way to make his story even more cohesive:

== From a 1998 piece in the Los Angeles Times titled “He’s a Hero — but it’s a Greek tragedy,” about his genetic influence: “The dead Greeks are way beyond me. Philosophy doesn’t move fast enough for me.”

== From 2001, as school’s sports information department cobbled together a dossier of stories before the NFL draft, it included this self-assessment: “I’m a walking contradiction. I’m the only person in the world who can sit on the fence and watch himself go by … I’ve always kind of been a little bit eccentric in certain situations. But if I don’t know the people, I’m kind of quiet … I’m not much of a social guy. I just read. I can’t add. I don’t have a mind for business. I don’t have a linear kind of mind. Not that I have any kind of mind.”

== A 2011 story in Los Angeles Magazine titled “The Loud Mouth” about inherent story-telling abilities, even if it becomes too much about his personal life:

“What I hear a lot is, ‘When I first started listening to you, I couldn’t stand you. I hated your voice. I thought you were obnoxious. I thought you were an asshole. Now I love you—I listen every day.’ I’m assuming that most people who do my kind of job don’t get that a lot because most people are less offensive. I want a reaction. With so many people in sports talk radio, you can almost hear the producer saying to the announcers before the segment, “OK, you take that side and you take this side and argue.” I never had to do that because my opinions get enough of a reaction without having to contrive something. I’ve always felt fortunate in that way.

“When I first started. I wrecked at least a dozen important relationships. Maybe more. If you put me in your wedding, I was going to talk about your wife. There was a time when all that mattered was the two hours on the radio, this little piece of my day. The theme of the show was ‘Everyone’s welcome and nobody’s safe.’ Being a little older now, I have more of a filter. It’s easier now because my life is more conventional. I’m married, and I go home at night, and my wife and I watch bad reality TV together. … I always enjoy telling stories and opening the door a little to my life. People have responded to me making fun of myself and calling myself fat or ugly.”

The good, bad and never-ugly parts of Papadakis’ story surface as problematic as they are apropos.

To become first-team All-CIF Division II at running back and strong safety for a 11-2 Peninsula High of Rolling Hills football team of 1994, Papadakis ran for more than 2,000 yards and scored 22 touchdowns as a senior.

In the Panthers’ final regular-season game, Papadakis ran for 232 yards in a 31-0 win over Santa Monica as the team ran away with the Bay League title and No. 1 ranking in the L.A. Times prep polls.

In the playoff opener, Papadakis piled up 187 yards rushing in a win over Canyon. In the quarterfinals, he ran for 235 yards, including a 80-yard TD run, in a 17-0 win at Arcadia.

That all gave Papadakis a runway to a college football career.

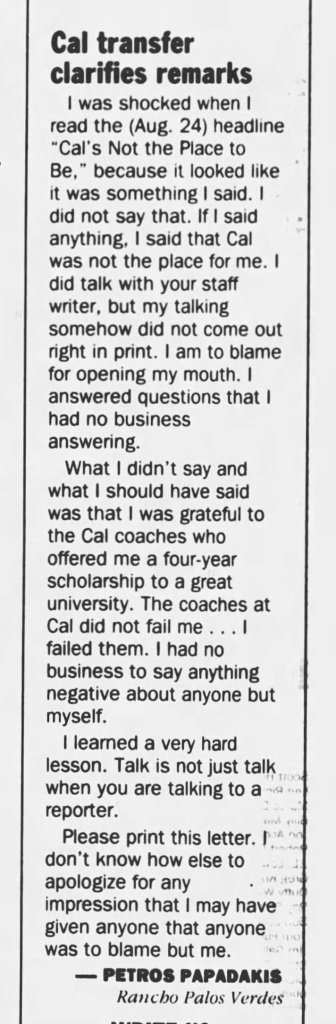

He accepted a scholarship to play at Cal in 1995.

“I wanted to be a Berkeley poet-sage,” he said in 1998. “I loved the whole beatnik thing.”

What he didn’t anticipating was getting homesick after spending the summer there and then participating in just three fall practices. He left his dorm and just went home. Cal head coach Keith Gilberton let him go as long as Papadakis promised not to play for another Pac-10 school for a year.

“I wasn’t ready emotionally, so I came home,” Papadakis explained. “It was a bad decision to go to Cal and it was a bad decision to leave. It still bothers me in the sense that I signed a scholarship, made a commitment to them and didn’t fulfill it. But it would have happened anywhere because I was unprepared. I respect incoming freshman, because I know what they go through.”

USC head coach John Robinson took him in as a walk-on and had him redshirt in 1996, where his older brother, Taso, was already playing.

That Petros Papadakis latched onto No. 22 — an ode to the Joseph Heller book, “Catch-22″ — was hardly a surprise for the English/American Lit major, who says he was obsessed with Jack Kerouac in high school, got into Kurt Vonnegut and was ready to turn the page on a new football journey. (Papadakis also knows that Heller first wanted to title his book “Catch-18,” but the publication of Leon Uris’ “Mile 18” at the time persuaded Heller to change the number. “Catch-22” eventually became part of the English language as a way to describe a situation that’s impossible to achieve because of a circular, irrational set of circumstances).

Taso Papadakis, a third-year junior, had been playing inside backer, wearing No. 53. He was moved to fullback, and his number was flipped to 35. Then came a second ACL knee mishap, and knew his career was finished. As Petros drove Taso back down the Harbor Freeway home to San Pedro after practice, Taso made an emotional plea for him to wear No. 35. Petros honored it.

In recent USC history, No. 35 had been stashed away by the head coach to bestow on an outstanding middle linebackers — Ricki (Gray) Ellison (1978 to ’82), Rex Moore (’84 to ’87), Scott Ross (’87 to ’90) and Jeff Kopp (’91 to ’94). To be honest, it was also a white player. Black players had No. 55.

Nonetheless, Petros Papadakis took ownership of No. 35 — he admired how it looked on Pro Bowl fullback Christian Okoye, a Azusa Pacific star then with the Kansas City Chiefs. Papadakis was also a fan of how it fit Chicago Bears Pro Bowl running back Neal Anderson. He loved Scott Ross, the former USC linebacker, and took pride in 35.

Earning a scholarship in 1997 as a backup tailback and special-teams player, Papadakis had his moment in a 45-21 win over Stanford — 54 yards on seven carries. That was the bulk of his season-total of 103 yards on 24 carriers for a 4.3 average.

Paul Hackett, who replaced Robinson as the USC head coach in 1998, started Papadakis four times at tailback (as Chad Morton was injured). Papadakis played in all 13 games and average 3.9 per carry (365 yards on 93 rushes) with a team-best eight touchdowns.

In what would end up a 32-31 Trojan loss to his former team, Cal, Papadakis opened the scoring with a 65-yard touchdown run four minutes into the game. Another 58-yard TD run was called back because of a late penalty behind the play, reducing it to a 41-yard pickup. The next week, in a 42-14 win at Washington State, Papadakis had a 53-yard touchdown in the second quarter that put the Trojans ahead for good.

In a 28-19 Sun Bowl loss to Texas Christian in El Paso, Tex., where future Heisman winner Carson Palmer started as a true freshman, Papadakis contributed a 2-yard TD run, and the Trojans ended up 9-4.

In fall camp of 1999, Papadakis suffered a crippling break of his right foot. It required multiple surgeries and an entire season was missed. The Trojans went 6-6. Palmer only played three games that season as well had had to redshirt as well.

Papadakis wasn’t sure he’d even be able to come back from this setback. His nature wasn’t to sit back and quietly heal.

“I was a violent player, and I had to play that way,” Papadakis said. “Otherwise, if I wasn’t violent enough, I wouldn’t play. I had to get violent to get to the top of the depth chart and I paid my dues in practice more than in games. Practices were wars. I remember times getting hit — not often, but not infrequently — when your face just ‘turns off’ and then it turns back on again. It happened in a game once at Oregon State and it was a horribly frightening moment. It freaked me out.”

In the 2000 season opener against Penn State at Giants Stadium in East Rutherford, N.J., Papadakis was named a team captain for his inspirational comeback journey. He sparked a 29-5 win for the No. 15 Trojans over the No. 22 Nittany Lions with a 2-yard TD run on his first carry back from the injury.

In Week 3, he had a three-TD game, including the game-winner with 2:34 to play, in a 34-24 triumph over San Jose State, boosting the Trojans to a No. 8 national ranking.

What happened after that has allowed Papadakis to brand himself as “captain of the worst USC team in history.”

The Trojans went from a 3-0 start to lose five in a row and seven of their last nine, despite a roster with Palmer, Troy Polamalu and a dozen players who ended up in the NFL. Papadakis’ team-best eight rushing TDs, all from 5-yards or less, lead to his being voted USC’s Most Inspirational Player.

Playing football was done. Talking football for a living had already started.

Papadakis’ gravitational pull for sportswriters pursing original quotes had already led to his becoming a regular Tuesday afternoon guest on Vic “The Brick” Jacobs’ AM-1150 sports talk show in 1998.

“The bureaucracy of the university encourages me to be eccentric on that show,” Papadakis admitted at the time.

He could divert to pop culture, music, TV, movies. Why authors John Updike and Sylvia Plath depressed him.

Papadakis could just be himself.

This was happening at a time when the sports-talk genre in Southern California was trying to figure out how it could make an impact in the 1990s, and make a radio station viable during the hours a live game wasn’t drawing attention.

Gene Autry’s station, KMPC-AM (570), was the first in Los Angeles to flip to the all-sports format. It was 1992. Autry was convinced that this thing was working in New York with WFAN radio. He had his Angels as the anchor would be enough of a draw. The main competition came from XTRA-AM (690), broadcasting from San Diego but whose 50,000-watt signal out of Mexico could blast into L.A.

Eventually, ESPN Radio came into the market on 1110-AM in 2000, then taking over 710-AM in ’03. Former all-news station KFWB-AM (980) also tried to make it with the branding “The Beast” in 2014. There was XTRA-AM 1150, KMAC-FM 107.1, KWNK-AM 670. Personality driven hosts were central to this being successful, but L.A. lacked what many other big cities had — and NFL team to produce constant chatter/content. It had to be more creative.

With all that was thrown against the wall, Papadakis emerged as the 21st Century Sports Talk model for SoCal, breaking the perceived need for a hot take on a hot day.

With his playing eligibility done, Papadakis ramrodded straight into the media, seizing a fortuitous opportunity as insider for a USC football resurgence under another new head coach, Pete Carroll. He arrived in 2001 and would go 97-19 through the 2009 season, including four Rose Bowl wins, one national title (in the 2025 Orange Bowl) and a national title game loss (to Texas the next season). Papadakis matched if not exceeded Carroll’s energy. Maybe not incidentally, Carroll found the Papadakis Taverna as a frequent venue to recruit players, from Reggie Bush and LenDale White to Mark Sanchez, with Petros’ father, John, creating the mystique.

And who knew, Petros himself might even be waiting on their tables.

A radio career came as a complement to the TV work he had going on at Fox Sports Net West as a USC football studio analyst. Mark Houska, the news director for the cable channel’s nightly sports show, hired him for that spot, and then got him a pre- and post-game role on the Trojans’ football coverage for its 1540-AM flagship station in 2001.

That expanded to a sideline reporting gig. He co-hosted an hour each weekday morning on 1540 “The Ticket,” rebranded KMPC after those call letters became available. As he grew into that role, Papadakis was moved to new time slot and became the self-proclaimed “afternoon typhoon.”

Papadakis’ TV opportunities expanded to a high-profile job as a game analyst on FSN’s Pacific-10 Conference football package in 2004. He did the California State High School Bowl Championship for Fox Sports West. He would host programming for the Game Show Network and Spike TV (“Pros vs. Joes”) and appear on VH1 (“I Love the 90s”). A role on CBS’ “CSI: New York” as a sports-talk host.

He even carved out time to become the L.A. Sports Arena and Galen Center public address announcer at the USC basketball games.

By 2006, Papadakis admitted in an L.A. Daily News interview that his art to sports-talk was more about leaning into everything non-sports — relationship advice, old film reviews, over-the-top live commercials for Felix Chevrolet. There was also an occasional scolding from his father as a frequent Friday afternoon guest. Papadakis knew he a bit obsessive-compulsive, saying he was always trying to kick the habit of smoking Newports, drinking Jim Beam and eating a half-dozen cheeseburgers every day.

“I know people say I’m too loud, or exuberant, out of control, too much style over substance – that’s OK,” the then 28-year-old said. “But to me, the style is the substance. There are too many people who can tell you who won or lost a game. I’m far too passionate to let it end there. If I’m excited about something, I scream. I mean, when you’ve got a bad lisp like mine, it’s just easier to yell when I work myself into a frenzy. I get like a rat with his piece of cheese.

“I really just approach it day by day, just as I did when I was a player. I’ll work as hard as I can to be legitimate. I’ve always had a chip on my shoulder. And I’ll try to take this thing as far as I can until someone stops me.”

By 2008, Papadakis was paired with Matt “Money” Smith on a weekday drive-time show at KLAC-AM (570). He also had a weekly college football analysis segment for Fox Sports Net’s “Best Damn Sports Show.” As a human Tilt-A-Whirl, Papadakis became Fred Roggin’s studio foil on Sunday night’s for KNBC-Channel 4’s “The Challenge” post-NFL show.

People-pleaser Papadakis crammed as much of his life into a Hello Kitty backpack and ran around town, from studio to station, fueled with coffee, string cheese and Hot Tamales candy. Maybe an occasional Camel Light.

“I’ll make it happen, whether it’s a TV show or waiting tables (back at the family restaurant),” he said in 2008. “I want to give everyone my best effort.”

In 2014, NPR reporter Jon Rabe caught up for a story on Papadakis for KPCC-FM (89.3) “Off-Ramp” show. Rabe started his piece with the dictionary definition of “culture shock,” and then admitted:

“After spending four hours in the KLAC studio in Burbank a couple weeks ago with Petros Papadakis and Matt ‘Money’ Smith, I’m surprised I didn’t wake up talking to myself at the Smokehouse, with three or four martinis drained on the table in front of me. It was that weird. Loud, fast, stream-of-consciousness, sound effects, people talking in the studio when the mike is on. If KPCC is a Prius, the Petros and Money Show is a Camaro clown car. For all these reasons, the Petros and Money Show is the opposite of public radio — but in others, it’s a kindred spirit. Because when you strip out the focus on sports, and the frenetic pace, it’s actually two smart guys who seem to like each other talking about an astounding array of topics in a smart way.”

In another NPR appearance, a 2016 interview with KCRW-FM (89.9) host Robert Scheer, Papadakis talked about the implications of unionizing college football players and whether politics belonged on the field or in the locker room. The interview originated from Sheer’s USC classroom and evolved into a story on the Huffington Post.

“You’re about the only person I can get to talk honestly about what football does and does not do for a college campus,” Sheer told Papadakis.

It wasn’t uncommon for Papadakis to segue to a guest spot on Fox Sports’ “The Herd with Colin Cowherd” explaining the latest plot lines of “The Bachelorette” and why he was addicted to its premise.

It’s as if all those appearances worked for him as much as any time he could have spent on a therapist’s couch. Which was a place he said he also made time for to keep his sanity.

“I’ve learned to stay two yards away from where my emotions are — sometimes five yards away,” he said in 2018. “Doing what I do for work, that’s when I can get most emotional. I gotta stripe it raw for the radio show and perform, and sometimes I get hurt easily and more offended than in normal life.”

When Papadakis looks back at his time his wearing No. 35, he knows that more recently, it seems to have been somewhat restored to its rightful position. Middle linebacker Cameron Smith had it for USC’s roster from 2015 to ’18.

After Papadakis wore No. 35, however, it was given to former Crenshaw High standout Lee Webb (2002 to ’04), who played primarily tailback. In 2010, freshman linebacker Hayes Pullard, also out of Crenshaw, was given No. 35, but he changed to No. 10 his final four years (2011 to ’14) as he became one of the team’s top tacklers.

Papadakis said he “got a little depressed” when No. 35 showed up among those relegated to Trojan kickers and punters. At one point, punters Kyle Negrete (2011 to ’12) and Chris Albarado (2011 to ’14) shared it.

“One of the kickers ran a fake-punt, there were a bunch of pictures of him scrambling on the internet and people thought it was me,” said Papadakis. “I’m like, ‘Dude, c’mon .. I didn’t look that way.’ The number needs to go back to the linebacker. To me, Scott Ross was a hero. It languished after I left.”

Married to wife, Dayna since 2006, Papadakis says he has been able to seen each of his two children wear his No. 35 while playing on their own baseball, soccer, basketball or football teams.

“It’s cool to see the ‘Papadakis 35’ on their backs now,” he admitted.

In a 2018 video profile for a Travis Matthews “life on tour” series, Papadakis said his career goal was to “remain upright and employed.” He also had some thoughts about those who’ve pushed back about the way he’s cannonballed into his media life.

“I’m not going to pretend that sometimes what people say isn’t a kick in the nuts. It’s the business. We need to take ourselves less seriously. We’re calling a college football game, not signing the Magna Carta. … We’re not splitting atoms. We’re just entertaining people.”

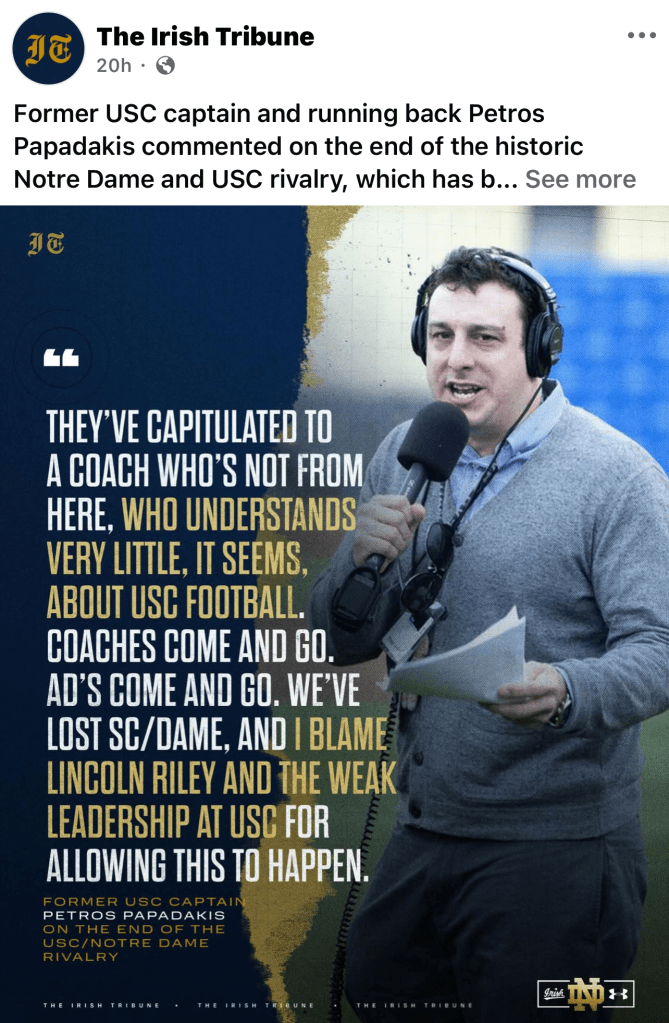

Papadakis balances weekday radio work with weekend college football TV assignments with Fox Sports on the Mountain West and Big Ten.

He’s never too far away to be a guest commentator for someone ‘s show or newspaper column especially f there’s a need for a fresh take on something such as the USC-Notre Dame football rivalry, and why it should never be tossed aside no matter what coach or other sports-talk host floats the idea to lighten up the Trojans’ schedule.

In 2022, Papadakis was the first inductee into the Peninsula High Athletic Hall of Fame. He was in the school’s inaugural freshman class, having come over from San Pedro High.

The campus is the same one what had been called Rolling Hills High when his father, John, attended it in the 1960s.

“I was somebody who struggled in high school like a lot of young people do,” Petros said at the time. “I was not a good student. I struggled getting along with my parents. I had a lot of issues with self-image and wanting to be accepted.

“Whether I like it or not, football has given me an identity. People listen to me talk about things that I have no business talking about, like literature and movies and all kinds of stuff, because of my identity as a football person. It’s been a door my entire life.”

Who else wore No. 35 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

Sidney Wicks, UCLA basketball forward (1968-69 to 1970-71):

The bridge in UCLA seven straight NCAA titles between the end of the ‘60s and Lew Alcindor and the start of the ‘70s with Bill Walton, Wicks was lured to Westwood from L.A.’s Hamilton High, a 6-foot-8, 225-pound forward/center who was part of three championships in his three varsity seasons. In his three seasons, UCLA was 86-4 and he combined to average 15.8 points and 9.9 rebounds. As a junior, averaging 18.6 points a game, he was Most Outstanding Player of the 1970 Final Four when he had 17 points and 18 rebounds against Jacksonville’s Artis Gilmore in UCLA’s 80-69 title triumph at Maryland. As a senior, averaging 21.3 points a game as the Bruins held the No. 1 spot in the polls from start to finish in 29-1 regular season, Wicks was a consensus All-American. A 1985 inductee into the UCLA Athletics Hall of Fame, Wicks was inducted into the College Basketball Hall of Fame in 2010 and into the Los Angeles City Section CIF Hall of Fame in 2013. He spent a semester at Santa Monica College a year before he could attend UCLA to get his grades up, and he ended up as an Academic All-American in 1971 with a degree on sociology. The No. 2 overall pick by Portland in the 1971 NBA Draft, Wicks had 10 years in the NBA, a four-time All Star winning Rookie of the Year honors in 1972 with a career-best 24.5 points and 11.5 rebounds a game.

Bob Welch, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1978 to 1987):

Welch entered baseball’s prime-time spotlight, World Series, L.A.-vs-.N.Y. style.

As an untested 21-year-old rookie when Tommy Lasorda brought him out of the bullpen with one out in the ninth inning and the Dodgers holding a 4-3 lead over the New York Yankees at Dodgers Stadium in Game 2 of the 1978 World Series. With the tying run on second and go-ahead run on first, Welch got Thurman Munson to fly out to right. With nine straight fastballs — a swinging strike, four foul balls, and three balls putting the count at 3-and-2, Welch then struck out Reggie Jackson on a giant swing-and-miss to end the game and secure a 2-0 series lead. (By Game 4, Jackson had a 10th-inning, walk-off single at Yankee Stadium against Welch to allow the Yankees to tie the series at 2-2. By Game 6, back at Dodger Stadium, the Yankees finished winning four in a row, featuring Jackson’s two-run homer off Welch in the seventh inning).

An All-Star in 1980 when he went 14-9 with a 3.29 ERA, Welch threw a 1-0 shutout against Cincinnati in June of ’83 and hit a home run in the sixth inning to provide the game’s only run. Welch posted his best WAR season with an NL-leading 7.1 in ’87 when he was 15-9 with a 3.22 ERA and four shutouts over a career-high 251 2/3 innings. But the next season, Welch was a key part of a three-team trade that sent him to Oakland to procure shortstop Alfredo Griffin and reliever Jay Howell, two key parts in the Dodgers’ 1988 World Series win. Welch won the AL Cy Young in 1990 for posting 27 wins, a number unmatched since then. Retired by 37, Welch died at 57 after an accidental fall at his home. His 1981 book, “Five O’Clock Comes Early: A Young Man’s Battle with Alcoholism,” Welch was one of the first pro athletes to openly discuss his disease.

Cody Bellinger, Los Angeles Dodgers first baseman/center fielder (2017 to 2022):

A six-season span with the Dodgers saw Bellinger quick reach the top — the NL Rookie of the Year Award in 2017, the 2018 NLCS MVP against Milwaukee that pushed the Dodgers into the World Series, and the 2019 NL regulars-season MVP Award. At age 23, he posted a WAR 8.7 season with 47 homers, 115 RBIs, a 1.035 OPS and .305 average. But his final three seasons in L.A. were WAR numbers of 1.5, -1.6 and 1.3 (with salaries of $11.5 million, $16.1 million and $17 million) as Bellinger battled injuries that included a separated shoulder from the 2020 NLCS suffered in delivering a high-five with teammate Kike Hernandez. His Baseball Reference similar scores and similar players to that point were with Dale Murphy, Reggie Jackson and even Roger Maris. The Dodgers let him to go free agency before the 2024 season, the Chicago Cubs too him for ’23 and ’24, and he was traded to the New York Yankees for ’25.

Jean-Sebastien Giguere, Mighty Ducks of Anaheim/Anaheim Ducks (2000-01 to 2009-10):

Giguere won the Conn Smythe Trophy in 2003 even as the Ducks lost to New Jersey in the Stanley Cup Final, but he ended up with the Ducks’ title team in 2007. Won 30 or more games for the Ducks in four out of five seasons in the decade of the 2000s. The Ducks got him in a trade with Calgary for a second-round pick in 2000.

Rudy LaRusso, Los Angeles Lakers forward (1960-61 to 1966-67): One of the young stars with Jerry West and Elgin Baylor who made the move from Minneapolis to L.A. after the 1960 season, LaRusso was a three-time All Star with the Lakers, averaging 14.1 points and 9.4 rebounds a game in his eight seasons. He also accumulated many nicknames — Deuce, The Ivy Leaguer With Muscles (he went to Dartmouth), Honey Boy, Musty, Brutus and Roughhouse Rudy.

Loy Vaught, Los Angeles Clippers (1990-91 to 1997-98): The 13th overall draft pick out of Michigan by the Clippers in 1990, Vaught was a 6-foot-9, 230-pound power forward who peaked with 17.5 points and 9.7 rebounds a game in 1994-95.

Tank Younger, Los Angeles Rams running back/linebacker (1949 to 1957): Staring out with No. 11 from 1949 to ’51, Younger, a 6-foot-3, 225-pounder from Grambling, switched to No. 35 when he was moved to fullback. His four All-Pro seasons with the Rams including averaging a league-best 80.5 yards a game rushing in 1955 and an average of 6.7 yards a carry in ’54. In 100 games for the Rams over nine seasons, Younger ran for 3,296 yards, 31 touchdowns and an average of 4.8 yards a carry. In the 1951 championship win over Cleveland, Younger, at right halfback, had the longest run from scrimmage (14 yards). He shared Pro Bowl honors that year with teammates Elroy Hirsch, Dan Towler, Bob Waterfield and Norm Van Brocklin.

Fred Slaughter, UCLA basketball forward (1960-61 to 1963-64): The 6-foot-5 center was on Coach John Wooden’s first NCAA title team as a senior in 1964 during its 30-0 season. As a freshman at UCLA, he lead that team to a 20-2 mark as the leading scorer (18.9) and rebounder (15.3) per game. Slaughter also competed as a freshman on the UCLA track and field team in the 100- and 220-yard dashes, high jump, shot put and discus. UCLA’s senior class president in 1963-64 got a masters at UCLA in business administration and a law degree at Columbia before becoming a sports agent and attorney. He was inducted into UCLA’s Athletic Hall of Fame in 2004.

Have you heard this story:

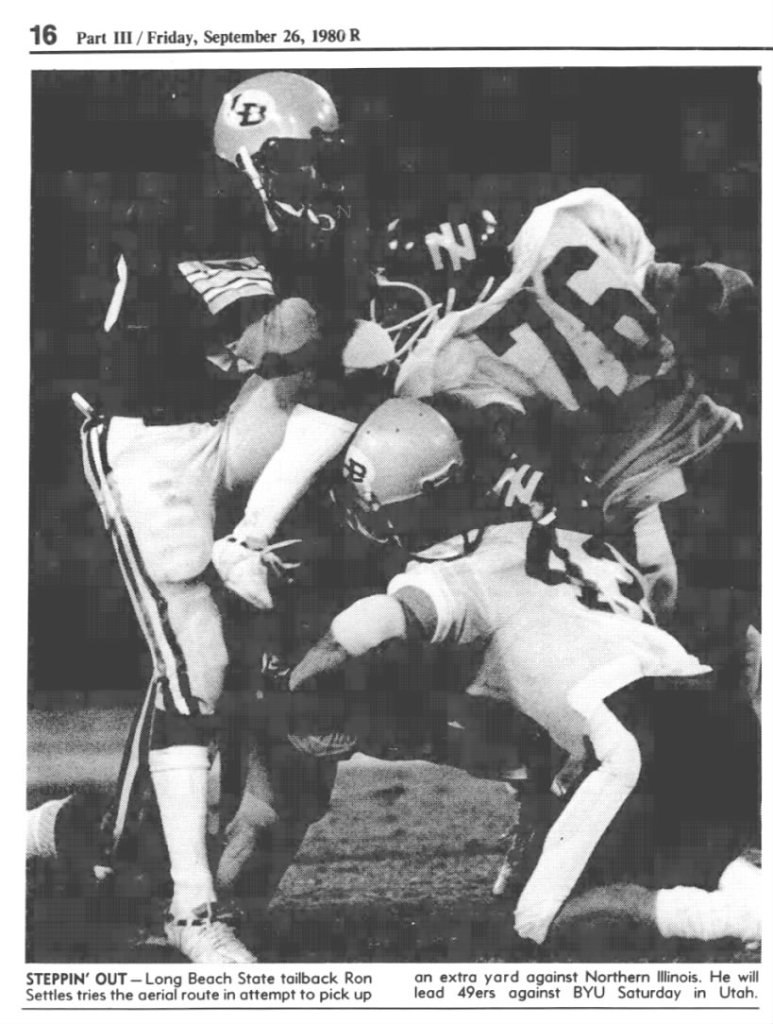

Ron Settles, Long Beach State football running back (1977 to 1980):

The 1981 unsettling death of Settles in a small Signal Hill jail months before he was to enter his senior football season at Long Beach State played out as the latest example of unchecked police racism and brutality. Anthony Pignatario wrote for the Long Beach Post in 2022: “Decades before George Floyd, Eric Garner, Sandra Bland or Freddie Gray became household names following their deaths while being arrested or in police custody, Ron Settles’ death made national news.”

In his senior year at Banning High in Wilmington, Settles became the short-yard, hard-charging fullback, helping his team to a 34-0 win over Cleveland in the L.A. City 4A Section title game at the L.A. Coliseum to cap a 12-1 season. The star of that team was tailback Freeman McNeil, who had 207 yards and three long TDs on a bad ankle in the champion. Settles did a lot of the grind work — nine carries for 44 yards as well as serving as McNeil’s lead blocker. Settles’ senior season saw him gain 703 yards on 123 carries for nine touchdowns. As a junior, Settles actually made more an impact in the backfield than McNeil, who had been injured, while Banning charged to the City title game, an eventual loss to San Fernando.

While McNeil went to UCLA and NFL stardom, Settles took recruiting trips to Washington and Hawaii but was more comfortable at nearby Long Beach State to continue his playing where he could be closer to his parents.In his first game for the 49ers in 1977, Settles picked up 67 yards rushing on eight carries, had one reception for six yards, and he set up a touchdown with a 75-yard kickoff return during a win against Fullerton — but he left the game with a dislocated elbow. He eventually took a red-shirt year because of the injury.

He came back to play nine games in 1978 and did more as a receiver and kick off return man. Settles then led the 49ers in rushing as a sophomore (663 yards on 131 carries) and as a junior (432 yards on 109 carries, despite missing four games with a broken rib). Dave Currey’s teams were a combined 15-7 (8-2 in the Pacific Coast Athletic Conference) in that two-year stretch.

Going into his senior year, Settles’ career stats of 32 games covered 1,322 yards rushing (4.4 yards a carry) and two touchdowns, plus 201 yards receiving on 23 catches, and 850 yards on 39 kick returns. He was already in the Long Beach State top 10 of all-purpose yards.

In a September 1980 feature story in the Los Angeles Times, Settles said he knew he exposed himself to too many hits when he carried the ball because he changed direction often. “I’m trying to get to a point where I can shoot direct at where I want to go, but when I see people coming, my mind automatically thinks of going here or there. … Every running back is going to take his share of shots. The good shots, the one you feel, you don’t see them coming. They’re the ones that hurt.”

Curry added: “His feet as as quick as anybody I’ve ever seen. He has got to learn to hang onto the football more aggressively. Sometimes his running style gets him into trouble. … I haven’t seen too many people tackle him one-on-one. He is quite a competitor.”

Settles was driving to a part-time student teaching job at Franklin Middle School in Long Beach when took a shortcut through Signal Hill on Orange Avenue near East Hill Street. It was about 11:30 a.m. He was pulled over, cited for speeding and said to have a small amount of cocaine on him. The next day, Settles, 10 days short of his 22nd birthday, was said to have committed suicide in a jail cell with a noose created by a mattress cover. The police reports covered up and had their own version of what happened.

Settles’ parents, Donnell and Helen, would not accept the story they were given about their only child. They teamed with attorney Johnnie Cochran to file a $50 million lawsuit against the Signal Hill police. A jury in a L.A. coroner’s inquiry ruled Settles “died at the hands of another, not by accident.”

While no officers were prosecuted in Settles’ death, the city paid the family a $1 million settlement. The death, one of several high-profile incidents involving police in the 1970s and ’80s, was one of the first to lead to a revamping of procedural changes in how jail areas were videotaped and arrests were recorded.

“I see a young man full of life gone,” Curry told the Boston Globe in June of ’82. “I ache for his parents and for those who knew him. But no matter what we do or what we say, nothing’s going to bring him back.”

The Ron Settles Memorial Foundation was started by several of Settles’ family members with the mission “to turn our pain into purpose by furthering efforts to empower individuals, creating and promoting opportunities to help end social injustice and systemic racism.”

The Signal Hill City Council approved that June 2, 1981 — the month and day of Settles’ death — be recognized annually as the Ron Settles Day of Remembrance.

“Ron Settles is Signal Hill’s George Floyd,” Signal Hill Mayor Edward Wilson said at the 2021 event, referring to the man murdered by a Minneapolis police officer in 2020 that sparked a national Black Lives Matters movement. “His death while in the custody of the Signal Hill Police Department is a tragedy that Signal Hill is known for even to this day.”

Christian Okoye, Azusa Pacific College football (1984 to 1986):

The 6-foot-1, 260-pound fullback known as “The Nigerian Nightmare” played six seasons in the NFL with the Kansas City Chiefs. But he had never played football until he arrived at NAIA Azusa Pacific as a 23-year-old, two years after coming to the United States from eastern Nigeria. Okoye was more into track and field — the shot put, discus, long jump and hammer throw. But when the Nigerian government declined Okoye’s plea to compete for its country in the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles in his sports of expertise, Okoye was convinced to try football, putting his 4.45-second speed in the 40-yard dash to use as a mammoth ball carrier. Azusa Pacific offered no full athletic scholarships so Okoye worked as a janitor and dorm-room painter to enroll. As coach Jim Milhon said: “The first time I handed Christian the ball, he looked at it curiously and said, ‘Very interesting…but very impractical.’ “In ’84 at APU, the Cougars won their last seven in a row with Okoye in the backfield, finishing 7-3. They won their first seven in a row to start the ’85 season and went 7-1-1. APU was 5-2-2 in his senior year of ’86 when he established a school-record 1,680 rushing yards and 21 touchdowns. He set 14 school records including career marks of 3,569 yards on 528 carries (6.76 per carry) and 34 touchdowns. In 1986, Okoye had more rushing yards per game (186.7) than any college runner on any level. He scored four touchdowns in the Senior Bowl and was named the team’s most outstanding offensive player.

As NFL scouts took notice, a 1987 Sports Illustrated story titled “A Bruiser from Azusa” noted that the 25-year-old Okoye, sporting a 34-inch waist and 28-inch thighs, was squatting 725 pounds, benching 405 and power-cleaning 395 before stepping into an NFL camp. In 1986, when he was inducted into the Azusa Pacific Hall of Fame, his bio called him “arguably the most celebrated athlete in Azusa Pacific history (with) equal justification for his Hall pass either through track & field or football.” It noted he was a nine-time NAIA champion in track and field, leading APU to four straight NAIA Outdoor Track and Field national titles (1983 to ’86) and a two-time Indoor champioships. He was also a two-time NAIA All-American first team pick in football. On the track, Okoye was a 17-time NAIA All-American and led Azusa Pacific to 4 straight NAIA Outdoor Track & Field national championship titles (1983-86).

During his time in the NFL, he became the Kansas City Chiefs’ all-time leading rusher, played in two Pro Bowls, led the NFL in rushing with 1,480 yards in 1989 and was the 1989 AFC Offensive Player of the Year. His 2023 autobiography, “The Nigerian Nightmare: My Journey Out of Africa to the Kansas City Chiefs and Beyond,” allowed Okoye to also explain how he established the Ontario-based California Sports Hall of Fame in 2006. Okoye was a 2016 inductee for his football career.

Scott Ross, USC football linebacker (1987 to 1990):

Out of El Toro High in Lake Forest, Ross was known for playing with abandon, not recklessless. With intensity and toughness. He was first-team All-Pac-10 for his final three seasons, all three trips to the Rose Bowl for the Trojans. As a senior, Ross was the conference defensive player of the year, first-team All-American and USC’s team MVP as well as its Most Inspirational Player. When Jeff Kopp was recruited to come to USC from Danville, California in 1990, he appreciated how Ross “took me under his wing, let’s call it the 35 mentoring program, and he told me about the tradition of the number. Practice hard, train hard, study film hard, simply outwork your teammates and opponents. When he graduated he said ‘the number is yours.’ That was a big deal to me.” The New Orleans Saints took Ross in the 11th round of the 1991 NFL Draft. When Ross died at 45, he was diagnosed with CTE. “He loved hard and he played hard and he screwed up hard, didn’t he?” said Marshall Ross at his son’s memorial service at Saddleback Church.

Mark Madsen, Los Angeles Lakers power forward (2000-01 to 2002-03): Madsen started in just 30 of the 183 NBA games he played in his first three seasons out of Stanford, but the 6-foot-9, 240-pounder nicknamed “Mad Dog” had a more visible impact during the Lakers’ victory parade celebrations of ’01 and ‘02. Madsen finished his career in Los Angeles — traded by Minnesota to the Clippers in the 2009 offseason, where he was then waived by his new team, but not before collecting $2.8 million owed to him from his Timberwolves’ contract, almost triple what he made in any season with the Lakers.

Dan Ardell, Los Angeles Angels first baseman (1961): During the expansion team’s first season Ardell got a September call up as a 20-year-old rookie. He got a hit in his first MLB at bat, a two-out, ninth-inning bloop single, but it ended the game before some 3,000 fans in Detroit because the runner ahead of him was caught rounding second base too far and was put out to end the contest. All in all, his seven games in a Halo uniform got Ardell, a standout at University High in Los Angeles who would be on a USC national title team, a 3,500-word writeup in the SABR Bio Project as well as a recent reminiscent feature story in the Los Angeles Times where the Laguna Beach resident said about how his pro retirement came as a 23-year-old: “I never had a desire to be a major league ballplayer. I loved playing baseball, but once I started playing professionally, I was bored. I was disinterested. If you don’t love what you’re doing, if you don’t appreciate and like what you’re doing, it becomes hard work.”

We also have:

Jim Gott, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1990 to 1994)

Chris Kaman, Los Angeles Clippers center (2003-04 to 2010-11) Also wore No. 9 for the Lakers in 2013-14

Mike Cuellar, California Angels pitcher (1977)

Tommy John, California Angels pitcher (1982 to ‘83)

Darcy Kuemper, Los Angeles Kings goalie (2017-18 and 2024-25)

Stephane Fiset, Los Angeles Kings goalie (1996-97 to 2000-01)

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 35: Petros Papadakis”