This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 56:

= Jarrod Washburn, Anaheim Angels/Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim

= Doug Smith, Los Angeles Rams

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 56:

= Hong-Chih Kuo, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Pedro Astacio, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Kole Calhoun, Los Angeles Angels

= Dennis Johnson, USC football

= Morgan Fox, Los Angeles Chargers

The most interesting story for No. 56:

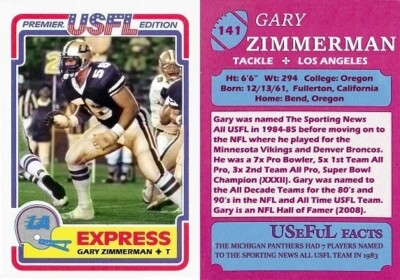

Gary Zimmerman, Los Angeles Express (1984 to 1985)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Fullerton, Walnut, Manhattan Beach, Long Beach, Los Angeles (Coliseum)

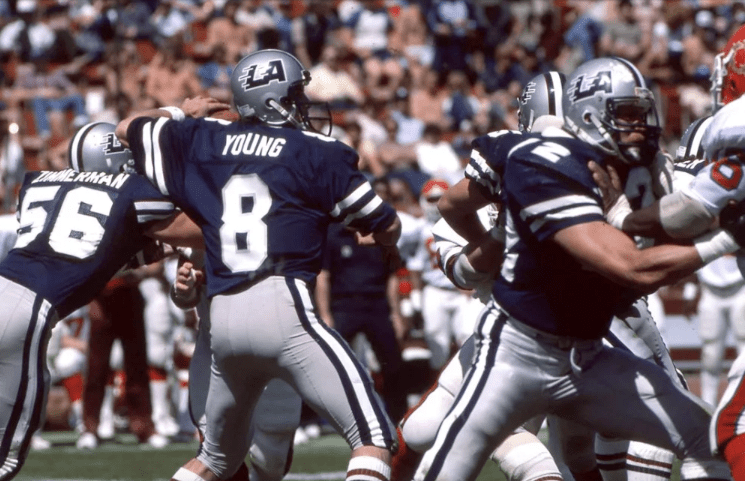

Gary Zimmerman had Steve Young’s back.

And in the 1980s, as a right tackle on the offensive line protecting a very mobile and ultra-valuable left-handed scrambling quarterback, that’s what blind-side mattered most for the insatiable Los Angeles Express of the equally mercenary United States Football League.

The Express gave soldier-of-fortune Zimmerman an X-factor platform to show his talents. It was career move that would reward the Fullerton-born, Walnut High standout who just finished a sparkling career at the University of Oregon with a chance, on paper, to earn millions while he figured out his life’s true ambitions.

There was risk to the reward — unnecessary injury, professional ridicule, growing-pain drama. But the fact Zimmerman ended up in the Pro Football Hall of Fame with a bronze bust after all was done gives that USFL/Express experience an exclamation point.

That crazy spring league wasn’t a bust for him.

The United States Football League had a name that seemed to demand a sense of duty to country and capitalism for any able-body college player wanting to serve a greater purpose. Specifically in the calendar months between Presidents Day and the Fourth of July — and you gotta work on Easter Sunday.

The Express was one of its original dozen teams to capitalize on this opportunity when the USFL sprung up as a spring league in 1983. It would go away ingloriously in 1985, buried in court documents.

The USFL, in the end, may have seemed to be a few vowels short of being really useful. But it actually was for guys like Zimmerman.

The Express tried to make itself/themself — we’re still unclear of a plural possessive for a noncount noun serving as a sports team name — as NFL-ready as possible for when the day came to migrate all its talent under contract to a September-to-Super Bowl schedule. There were, alas, too many other rouge owners that had similar ideas (see: Trump, Donald; New Jersey Generals), but L.A. was always a place where things could happen. Usually it had better weather during any business storm.

While there was plenty of local talent to pick from at USC and UCLA — including the first two headliner quarterbacks with Mike Rae and Tom Ramsey — the Express had ownership that pushed for bigger and better. Bill Oldenberg, who came out of seemingly nowhere with bags of money for team general manager Don Klosterman, wanted to have the greatest haul of college prospects for the 1984 season as the city was already ramping up for the Summer Olympics.

That started with the pursuit of Young, whose career as the scrambling/rambling quarterback at Brigham Young University had offensive coordinators as worried as excited about what he might do.

Still, before Young could be brave enough to sign what was called the richest deal in pro sports history — $40 million over 43 years, which, in all practicality, was $5 million over the first four seasons, and a $37 million annuity — he and his advisors had to make sure there was as much physical protection in front of him on the field as the team was pledging the financial wherewithal.

That’s where the 6-foot-6 and 264 pound Zimmerman became part of a package deal, the mass signing of massive men-children tasked for this experiment.

Zimmerman, who would end up in the University of Oregon Sports Hall of Fame in 2002, was called by Ducks head coach Rich Brooks as the best lineman he had ever had on his teams. Zimmerman was the 1983 Morris Trophy winner, given to the Pac-10’s outstanding offensive lineman. He was a third-team All-American by AP and UPI.

He did it wearing No. 56 — and that would be the number he kept for his Express wardrobe.

At the time of the January ’84 draft, football experts said the Express had six players who could have been consensus first-round NFL picks if they just waited a few more months. Aside from Young and Zimmerman, there was offensive tackle Mark Adickes of Baylor, center Mike Ruether of Texas, defensive tackle James Robinson of Clemson, defensive end Lee Williams of Bethune-Cookman and defensive back Allanda Smith of Texas Christian.

Zimmerman was a second-round pick in the ‘84 USFL open-school draft. Adickes and Ruether came from Houston’s Gamblers for “future considerations,” even if no one know what the future of the USFL held. The Express also dipped into the NFL free-agent pool, signing Jeff Hart, a five-year starter on the offensive line for the Baltimore Colts who once protected quarterback Bert Jones.

By mid-February, the Express signed Zimmerman, Adickes and Ruether. Each got what was said to be a four-year, $5.9 million deal.

Young had the thunder herded in front of him so he could bide his time and operate in the pocket, and pick the pockets of opposing defensive backs.

“I have no second thoughts at all,” said Zimmer of passing on the NFL to sign with the Express. “I heard I could have gone anywhere from the first 10 to the end of the first round, but the way I calculate that, I would have ended up on the East Coast. That’s not where I wanted to be. I still think about my buddies who are waiting for the (NFL) draft. They’re still looking for a job. But I’m glad I already have one.”

The team headquarters, originally at Long Beach State, moved to a converted elementary school campus in Manhattan Beach next to a popular public gathering spot called Polliwog Park. Members of the stockpiled Express could be seen as tadpoles in the pro football hierarchy, but they were swimming in talent. Everyone into the pool.

Zimmerman started all 17 games for the 10-8 Express in 1984, a team coached by John Hadl that tied with Arizona for the Pacific Division lead in the Western Conference. Zimmerman helped Young throw for 2,361 yards and 10 TDs versus nine interceptions as well as rush for 515 yards on 79 carries (6.5 yards a carry, among the league leaders) and seven touchdowns. The team was fifth in the USFL with just 38 sacks allowed. The Express outlasted Michigan, 27-21, in a three-overtime thriller at the Coliseum to open the playoffs on July 1. The Express lost at Arizona 35-23 in the conference championship.

In the offseason, the USFL owners voted to move to a fall schedule by 1986.

During the ’85 season, after some teams folded, merged and relocated, Zimmerman returned for 18 games for the Express, which shriveled to a 3-15 mark. Quarterback Young had to play fullback in the team’s final game, moved from the Coliseum to L.A. Valley college. Young still completed 137 of 250 passes for 1,741 yards and six touchdowns against 13 picks. The Express averaged a league-low 14.1 points a contest.

As the wheels were coming off the gravy train, Zimmerman at one point in that ’85 season walked out of training camp for a day and half because he said the Express had not put up an annuity payment on his contract. He had to take a number.

As the Express disappeared before the ’86 season, with the USFL not far behind, Zimmerman’s league rights at first became property of the Memphis Showboats. But in May of 1986, Zimmerman sued the USFL, contending he was free to negotiate with the team of his choice — particularly the NFL’s Minnesota Vikings, who had his rights after the New York Giants traded him there for two second-round picks. The suit contended Zimmerman was entitled to $675,000 for the final two years of the contract he signed with the Express, as well as 30 years of deferred payments totaling $3.095 million.

In the end, the Express would be lumped in a list of teams that had flashes of football drawing power but not a long shelf life. The Los Angeles Dons of the All-American Football Conference (1946-to’49, where Klosterman once played), the Hollywood Bears, Long Angeles Wolves and Los Angeles Bulldogs of the Pacific Coast Professional Football League (1940 to ’47), the Long Beach Admirals of the Continental Football League (1967) or the Los Angeles Xtreme of the XFL (2001).

As an NFL mainstay back at left tackle for the last dozen of his 14 professional seasons, Zimmerman started 184 games, including 169 in a row. The first seven years were in Minnesota (1986 to ’92) and the last five in Denver (’93 to ’97, finishing off with a Super Bowl XXXII title for the Broncos in San Diego). It covered seven Pro Bowls, three times as first-team All-Pro. He also bridged decades enough to where he was on the Pro Football Hall of Fame’s first-team All-1990s after he was second-team All-1980s.

He did all that wearing No. 65 — and, in some lists that ranked such thing, making him the greatest No. 65 in NFL history.

In Minnesota, he protected Tommy Kramer, Wade Wilson, Rich Gannon, opened holes for Herschel Walker, and was on a line with Randall McDaniel. In Denver, he protected John Elway, opened holes for Terrell Davis, and was on a line with Mark Schlereth.

But it wasn’t easy to get Zimmerman to say much about all that at the time. He was famous for his refusal to interact with the media. It came about after a time early in his NFL career when comments made by Zimmerman about the poor play by both the offense and defense in a Vikings’ loss was construed to be critical of the defense not playing well enough. When some teammates pushed back, Zimmerman put his foot down and refused to do interviews or engage in any sort of media interaction for the rest of his career.

The Pro Football Hall of Fame has five players whose career in the USFL helped make their case immortality in Canton, Ohio. Along with Young, Reggie White, Sam Mills and Jim Kelly, there is Zimmerman.

In his 2008 induction speech, Zimmerman spoke up. He recognized the coaching he received at Walnut High and the L.A. Express as part of the journey that got him there.

He also added that when he agreed to go to the University of Oregon, he did so because it was the only school that would sign him as a middle linebacker. But then he was given No. 75. He figured out the Ducks’ staff had different plans for him.

“The Dali Lama once said, ‘Remember not getting what you want is a wonderful stroke of luck’,” said Zimmerman in his speech. “The point I’m trying to make here is that nobody starts out wanting to play the offensive line position, it’s just where we end up. … Offensive linemen conform to the herd principle. It’s not good to be singled out for good or bad, and that’s why it’s difficult for me to stand up here alone getting this incredible honor. There should be a stage full of guys up here standing here receiving this honor with me.”

In preparing for the release of his 2018 book, “Football For A Buck: The Crazy Rise and Crazier Demise of the USFL,” Jeff Pearlman listed Zimmerman as No. 13 on his list of the 25 greatest players in USFL history.

Pearlman explained: “So why is he only 13th on this list? First, because he only played two USFL seasons. And second, because while he was terrific, Zimmerman could look left and right on the Express offensive line and see a conga of stars … paid big bucks to also block for quarterback Steve Young and his merry band of weapons. Ultimately, Zimmerman’s greatness developed as he went along.”

Even if he went with the USFL experience on his resume to make it all fall into place.

Who else wore No. 56 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

Jarrod Washburn, Anaheim Angels/Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim pitcher (1998 to 2005): His 18-win season and 3.15 ERA during the Angels’ World Series title run of 2002 led to a fourth-place finish in the AL Cy Young voting. He finished the year winning four of his final five stars with an ERA of 1.93 in September. Washburn also got the win in the decisive Game 4 of the ALDS over the Yankees. His eight-year run with the Angels resulted in a 75-57 record and 3.93 ERA.

Doug Smith, Los Angeles Rams center (1978 to 1991): A six-time Pro Bowl center out of Bowling Green started 160 of 187 games over his career, settling into the position after he played previous seasons early on as a right guard and right tackle. But that wasn’t anticipated at all when he went undrafted in the NFL after his college career ended. While Cleveland and Philadelphia wanted to sign him as a free agent, “the Rams offered me a little bit more money because I didn’t know that the cost of living was higher in L.A. than it was in the other places,” Smith once said. “They needed a long snapper, and I long-snapped since I was 10, so I thought that may be my way into the NFL.” A change in coaches from George Allen to Ray Malavasi to John Robinson made Smith’s career last even longer. Starting at right guard in 1980, and at right tackle the following season, Smith became the Rams’ first-team center in 1982. Two seasons later, his seventh in the league, he was chosen to play in his first Pro Bowl. “I guess part of it was proving people that didn’t think I was going to make it wrong,” he said of his career. “When I left on the plane (after signing with the Rams as an undrafted free agent), there weren’t too many people not expecting me to be back home in a few weeks,” Smith said.

Hong-Chih Kuo, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2005 to 2011): The Taiwan-born left-hander made it into 218 games over seven seasons (13-17, 3.73 ERA) with 14 starts — as well as an All-Star appearance in 2010, a season where he had a 1.20 ERA in 60 innings with 72 strike outs, 12 saves and a .211 opponent batting average. He got the first two outs in the fifth inning and gave up an unearned run, the only run the AL squad could muster as the NL posted a 3-1 win at Angel Stadium of Anaheim (as it was called) as Kuo’s Dodgers teammate Jonathan Broxton got the save.

Pedro Astacio, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1992 to 1997): The Dominican wore No. 59 for his first season and changed to No. 56 as he had a 14-9 record and 3.57 ERA in 31 starts the next year.

Kole Calhoun, Los Angeles Angels outfielder (2012 to 2019): A Gold Glove winer in 2015, Calhoun had a 2019 season with 33 homers and 74 RBIs.

Dennis Johnson, USC football inside linebacker (1977 to 1979): A three-year starter and first-team All-American as a senior and part of the Trojans’ 1978 national championship team, he was also first-team All-Pac 10 as a junior and senior.

We also have:

Morgan Fox, Los Angeles Chargers defensive lineman (2022 to 2024) (started wearing No. 70 and No. 97 for the Los Angeles Rams from 2016 to 2020).

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 56: Gary Zimmerman”