This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 59:

= Evan Phillips, Los Angeles Dodgers

= Ismail Valdez, Los Angeles Dodgers

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 59:

= Mario Celotto, USC football

= Loek Van Mil, Los Angeles Angels

The most interesting stories for No. 59:

Collin Ashton, USC football linebacker (2002 to 2005)

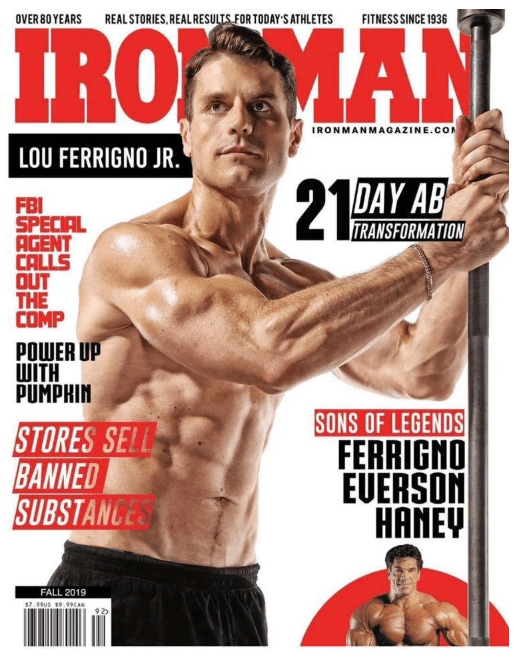

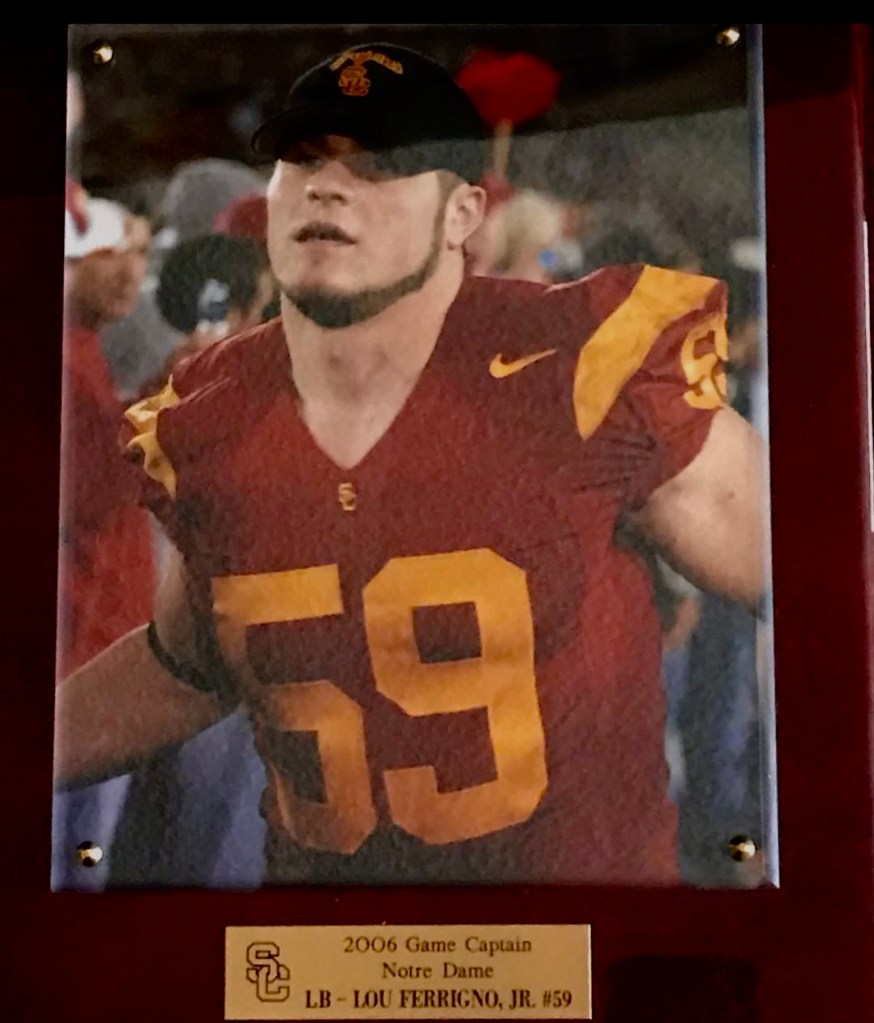

Lou Ferrigno Jr., USC football linebacker (2006 to 2007)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Mission Viejo, Sherman Oaks, Hollywood, Los Angeles (Coliseum)

Walk in the cleats of a college football walk-on.

It’s a fantasy football experience. Sometimes. Pay to play can be an expensive fantasy.

Some get movies made about them. Their “true underdog” experience.” At least one ended up being known as the “O-Dog.” He got wrapped up in nefarious escapades that were somehow worthy of a video screaming docuseries.

Two pendulum swing of the walk-on experiment from USC’s annals happened during the Pete Carroll Era of fame and fortune in the 2000s. Both were given No. 59:

= Collin Ashton, a kid from Mission Viejo who never missed a Trojans football since the day he was born, had four generations before him attend the school, and was just hoping he could be used a long-snapper. He ended up starting a few games at linebacker as a senior because they needed healthy bodies. All the way to a national title game.

= Lou Ferrigno Jr., the son of a Hollywood star/acclaimed body builder, knew his DNA alone wouldn’t be enough to get him a shot. He came, he tried, he got injured. He begrudgingly got into acting. He made a career out of that.

If a walk-on can act if he/she belongs, that’s half the battle.

Past performance doesn’t guarantee future results. Sometimes, it’s just worth taking a shot. If not for a teachable moment, it’s a fabulous barroom conversation of those glory days decades later.

The background

Hollywood helped make Dan Ruettiger the most glorified walk-on in college football history. The 1993 film, “Rudy,” was “92 percent true,” according to Ruettiger, who wore No. 45 at Notre Dame and became part of the Golden Dome mystique.

The scene where all the players put their jerseys on head coach Dan Devine’s desk in protest, threatening to quit if he doesn’t play Rudy? Didn’t happen. But it’s a scriptwriter’s divine right to twist a fact or two to add texture to an inspirational sports flick.

Ruettiger’s story hits the climax when he gets into the final Notre Dame home game of the 1975 season as a defensive end, sacking the Georgia Tech quarterback on the final play. He was carried off the field by teammates.

How does the walk-on experience work for most?

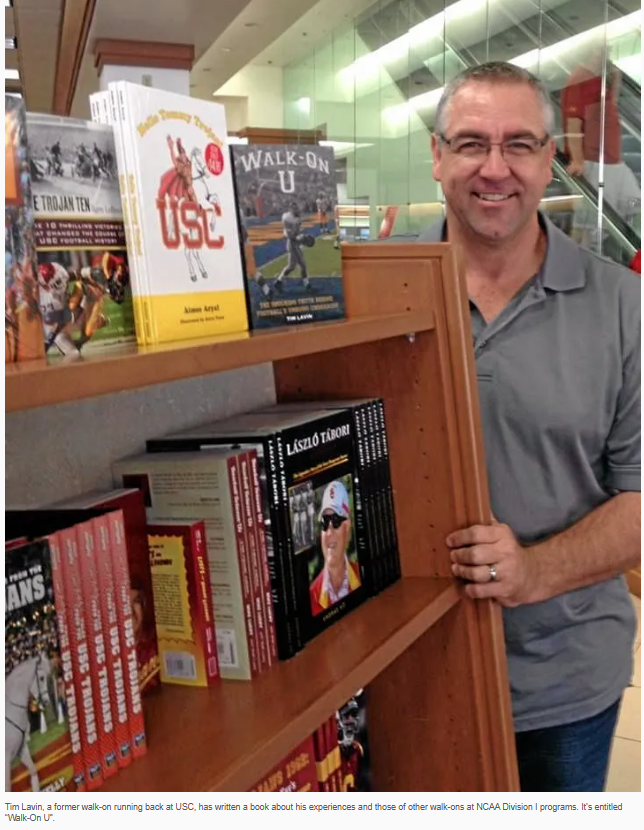

Tim Lavin’s time at USC came between Ruettiger’s actual moment on the gridiron for Notre Dame, and before the movie version of it that made it something to aspire to.

Lavin started at West Hills’ Chaminade High in the late 1980s, a running back who set the school’s single-season rushing record of 1,778 yards, was a CIF Division Player of the Year and was second in SoCal rushing and scoring stats to Crespi’s Russell White.

Lavin drew interest from Cal State Northridge, but nothing much from USC, except to be invited to play as long as he paid the tuition. Essentially, Lavin agreed to be a tackling dummy for scrimmages and back-up to the backups.

“Mad Dog,” as he was called by teammates, wasn’t mad about the idea of romancing anything he experienced when he wrote the 2013 book, “Walk-On U: The Shocking Truth Behind Football’s Unsung Underdogs.”

Whereas Ruettiger created the College Football Rudy Award in 2008 for his foundation, which honors Division I players who demonstrate the four “C’s”: character, courage, contribution and a commitment to their team, Lavin’s experiences, as chronicled in his book, it was more unkempt promises, class scheduling upheaval, and an unwitting victim of “the system.”

He had reason to be optimistic about receiving an eventual full scholarship from head coach Larry Smith, based on the words of some assistant coaches’ and positive responses by teammates like Junior Seau and Mark Carrier, but it didn’t happen. Lavin got an offer for a half scholarship in the spring of 1990. Smith told him there were budget cuts and that’s the best he could do. Marvin Cobb, an assistant athletic director at the time, disputed Smith’s claim. Smith refuted Cobb’s interpretation of the situation.

In a September 1990 Los Angeles Times feature, Lavin explained his predicament. He said his role as a walk-on versus a scholarship player: “It’s just like segregation. Everyone knows who the scholarship guys are, and everyone definitely knows who the few of us are who are not full-scholarship guys … We are the guys with the asterisks next to our names.”

Lavin got into 12 games in 1990, recording one carry for two yards.

In 2013, prior to the annual USC-UCLA football game, Lavin sat at in a booth at Traini’s restaurant in Long Beach, a place whose walls herald the careers of dozens of local college and pro football players.

As USC was in the second of a three-year NCAA sanction limiting them to 75 scholarships, a program that started the season with Lane Kiffin as head coach and then was headed up by Ed Orgeron and Clay Helton relied on 37 walk-ons that season. UCLA had 30 walk-ons among its 83 scholarship players.

“Most don’t even know what they don’t know when they start exploring the idea of the walk-on,” Lavin said, then the secretary of the Trojan Alumni Football Club.

“They’re not all going to be ‘Rudy.’ They have a hope and a dream that comes from every red-blooded American who believes that hard work will be rewarded. Maybe so in the corporate world, but there are so many things in place today by the NCAA that continues to pull you down just because you have ‘walk-on’ attached to your name.

“ ‘WO’ should not be a scarlet letter. I want to turn that into a term from a feeling of shame to one of admiration by showing people just what every walk-on is up against.”

In 2010, the Burlsworth Award was created to honor Brandon Burlsworth, a walk-on at Arkansas who became an All-American in 1994 and was killed in a car accident 11 days after being selected by Indianapolis in the 1999 NFL Draft. And, yes, a movie was made about him called “Greater: The Greatest Walk-on In The History of College Football,” based on 2001 book called “Eyes of a Champion, The Brandon Burlsworth Story.”

That award came before the player regarded as the most successful USC walkon in its program history emerged. Clay Matthews III, out of Agoura High, was another hunch addition to the USC roster by head coach Pete Carroll. Matthews kept his walk-on status for two years before he was given a scholarship as special teams player from 2006 to ’08 while playing reserve outside linebacker. As a senior he started and shined enough to become a Green Bay Packers’ draft pick and six-time Pro Bowler.

The 2025 USC football season saw running back King Miller (wearing No. 30) and twin brother Kaylon Miller (wearing No. 60) come from Calabasas High to work their way into the starting lineup. King Miller burst on the scene when he ran for 158 yards and a touchdown in 18 carries in a 31-13 win over No. 5 Michigan at the Coliseum in Week 7. He also had 217 all-purpose yards in the game with two receptions and two kickoff returns. That won him the Big Ten Freshman of the Week, Paul Hornung National Player of the Week and Burlsworth Trophy Walk-On of the Week. Kaylon Miller stepped in at right guard during a Week 9 win over Nebraska, posting an 88.2 pass block grade — third-best in the Big Ten. King Miller scored USC’s go-ahead touchdown on a 6-yard run in the fourth quarter, following Kaylon’s block to secure the Trojans’ 21-17 victory over the Cornhuskers in Lincoln, Neb.

In UCLA’s history, walk-on legends include quarterback John Barnes, who led his team to an improbable 1992 win over USC; wide receiver Mike Sherrard, who became a first-round NFL draft pick; and his coach was Terry Donahue, another famous walk-on Bruin. Brian Callahan, the son of former Oakland Raiders head coach Bill Callahan, was a walk-on backup quarterback at UCLA from 2002 to ’05, earned a scholarship his senior year, and was happy to just be the holder on field goals and extra points. After time as a UCLA graduate assistant, he ended up as the head coach of the NFL’s Tennessee Titans in 2024 (and let go in ’25 with a 4-19 record during his run).

Others in the college football world who went from walk-on to stardom as an NFL player: J.J. Watt (at Wisconsin), Josh Allen (at Wyoming), Baker Mayfield (a Heisman winner at Oklahoma), Stetson Bennett (at Georgia), Santana Moss (at Miami) and Jordy Nelson and Tyler Lockett (Kansas State).

The test cases

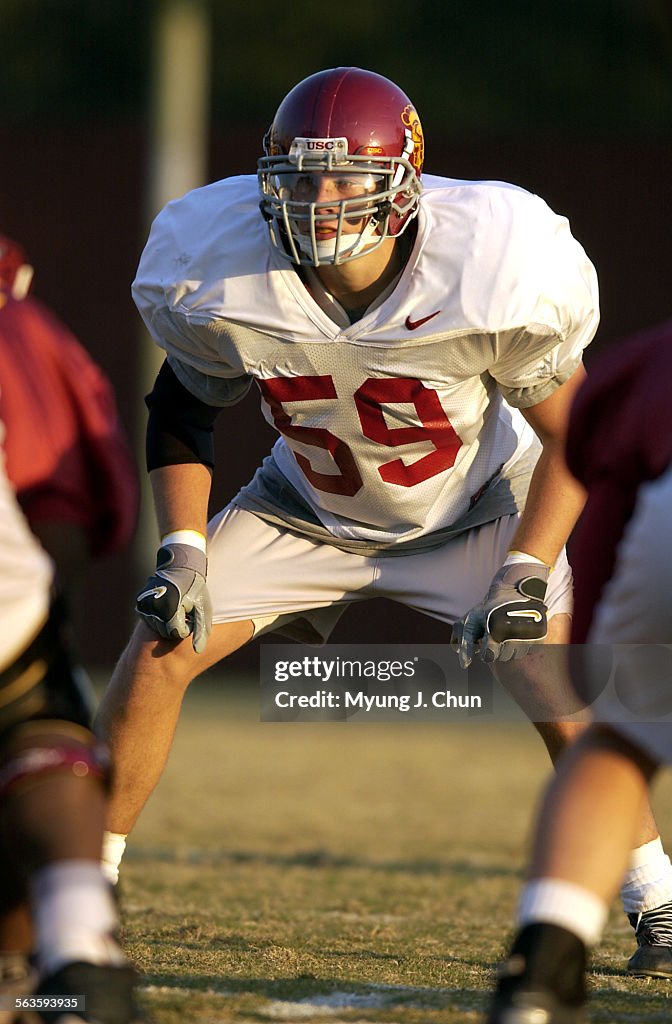

When linebacker Collin Ashton was introduced with the rest of the USC senior class prior to the No. 1 Trojans’ game at the Coliseum against No. 11 UCLA in 2005, he couldn’t have imagined it would be as a member of the starting lineup.

Ashton had attended and/or participated in every USC football game at the Coliseum since he was a two-month old in 1983. His father, grandfather, great-grandfather and great-great-great grandfather attended USC as well.

“I was brought up in a family where ‘SC is awesome and some other school is not,” he told the San Bernardino Sun. “I just kinda followed tradition, kept it going. The five generations thing didn’t really come up much.”

Mark Ashton, Collin’s dad, told the Orange County Register’s Mark Whicker in September of 2005 that the commitment was there to attend any USC home game that it took some innovation.

“He’d play a Pop Warner game in La Habra or somewhere on a Saturday morning and there’s no way we could get back home to Mission Viejo and still make the game.

So we’d pack these warm-water jugs, and open up the car doors and he’d get behind them and take off his uniform, and we’d basically wash him off right there. Then we’d go to the Coliseum.”

Ashton and his two twin younger brothers already worked their way into being ballboys at the USC basketball games when George Raveling was the head coach.

At Mission Viejo High, Ashton was a reliable long-snapper. Coach Bob Johnson alerted his USC contacts that Ashton could be worth checking out. Assistant coach Kenny Pola came to a Diablos’ practice to see for himself. It was worth the trip.

Beginning as a redshirt freshman in 2001 when Carroll first arrived, Ashton started his routine to suit up by putting on the same gray USC T-shirt that he first had as a 10-year-old.

“A lot of people didn’t think I could do it — a lot of them laughed at me and said I was wasting my time,” Ashton said about deciding to be a walk-on. “I’m not dumb. I looked out on the field in my first few weeks here and I could see everyone was bigger, stronger and faster than me. I knew it would be tough before I got here, but it was even worse than I thought.

“Every Saturday would come and I’d never get close to playing. But I knew why. If I was the coach, I wouldn’t have played me, either … Sometimes I would think, ‘I cannot do this for five years, no way.’… My whole goal was to win a scholarship here, to work my way up. So I kept working.”

As a walk-on, Ashton realized he couldn’t get into the weight room for training like some of his other teammates.

“I got really angry one time,” he said. “We had lifting sessions at 6, 8 and 10 a.m. I was only allowed to go at 6 and 8. I didn’t get up for the 6 and I had class at 8. So I show up for the 10 and they say no. That was tough. Little things like not being able to get a protein shake when you need to. Then again, it’s supposed to be tough. If you don’t love the game you’re not going to make those sacrifices.”

In 2002, he got into three games and made three tackles. As a sophomore in 2003, starting third on the depth chart at weak-side linebacker behind Melvin Simmons, Matt Grootegoed and Oscar Lua and Lofa Tatupu, Ashton played in all 13 games as USC went 12-1 and won the Rose Bowl. He piled up 28 tackles and forced a fumble as a backup linebacker and on special teams.

When he started in the Trojans’ 47-22 win over UCLA at the Coliseum, he became the second USC walk-on to start a game in the previous 20 years.

As a junior in 2004, Carroll gave Ashton a full scholarship as a long snapper on punts and backup middle linebacker.

“That’s my favorite thing to do here, give out scholarships like that, and it shows you how special Collin is when his teammates gave him a standing ovation,” Carroll said. “He came here undersized and not prepared for football at this level, but he did not believe that.”

“From what coach Carroll instills, being a Trojan is being someone who is always ready to compete,” Ashton said. “Someone who will do anything to be competitive.”

Ashton got into all 13 games as a junior, making 16 tackles. USC went 13-0 and won the national title against Oklahoma in the Orange Bowl.

“The story is crazy, man,” USC tight end Alex Holmes said of Ashton prior to the Orange Bowl. “I mean, really crazy.”

As a senior in 2005, with a USC linebacking crew that included Lua, Dallas Sartz and Keith Rivers, the Trojans went 12-0 into the 2006 Rose Bowl before losing the national title game to Texas. Ashton had ended up starting at all three linebacker positions because of injuries to teammates. He was third on the team in tackles with 54, had an interception and broke up two passes.

After the USC-Texas national title game, the 22-year-old Ashton retired his gray USC T-shirt.

“When you hold is up you can see right through it,” he said. “It really wasn’t a good-luck thing. It was just a routine. My dad wants it for some reason. He wanted to do something with it. I don’t really care.”

After playing in the Hula Bowl, Ashton got a look at by the San Diego Chargers but was released in May of 2006. Same with the Baltimore Ravens. But in 2007, he was a middle linebacker for the Flash de la Courneuve in Paris, France. The team won its Ligue Élite de Football Américain title. Ashton became the chief operating officer for a high-end property management company.

“(The former USC player) brings the same drive and determination from the field to the world of property management,” according to his website bio.

In October of 2006, a sports blog called “The Church of Albert” devoted to Florida Gators sports asked the question: If your favorite college football team was a super hero, what would it be?

Mike Penner of the Los Angeles Times found it interesting to note that Wolverine, appropriately, was assigned to the University of Michigan. Superman was given to Notre Dame. For USC, it assigned the Incredible Hulk.

“(Hulk) is an unstoppable force of nature that you do not want to get angry,” the site explained. “He sometimes turns into a meek little man that gets pushed around for awhile but eventually the Hulk bursts out and separates arms from shoulders. USC often puts forward meek-science-type efforts for three quarters, followed by a city-destroying fourth quarter that puts opponents away.”

It didn’t hurt at all that the site could also make the connection that, on the USC roster, Lou Ferrigno Jr., was waiting for his chance to burst onto the scene.

After Ashton departed USC following the 2005 season, Lou Ferrigno Jr. assumed No. 59 by Carroll.

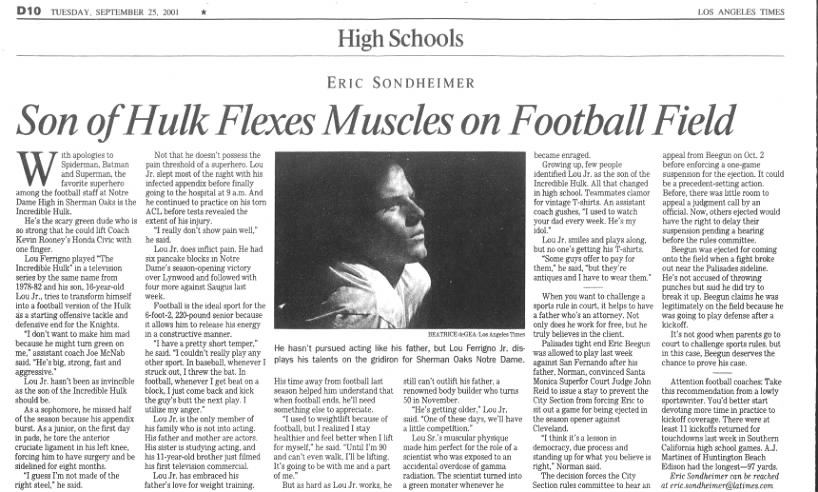

Ferrigno was a 6-foot-1, 230 pounder living in Santa Monica with his famous parents when he started at Loyola High in L.A., graduated from Notre Dame High in Sherman Oaks in 2002 and then went to Pima Community College in Tuscon, Ariz., before finding himself on the USC campus in ‘05.

During his time at Notre Dame High, a story in the Los Angeles Times gave up any thoughts he could stay under the radar. “Lou Ferrigno played ‘The Incredible Hulk’ in a television series by the same name from 1978-82, and his son, 16-year-old Lou Jr., tries to transform himself into a football version of the Hulk as a starting offensive tackle and defensive end for the Knights,” the story read.

Lou Jr.’s story included missing time as a sophomore because of a burst appendix and tearing the anterior cruciate ligament in his left knee as a junior.

“I guess I’m not made of the right steel,” he said. “I have a short temper. I couldn’t really play any other sport. In baseball, whenever I struck out, I threw the bat. In football, whenever I get beat on a block, I just come back and kick the guy’s butt the next play. I utilize my anger.”

On USC’s 2006 depth chart for the season opener, Keith Rivers, Rey Maualuga, Oscar Lua, Dallas Sartz, Brian Cushing and Kaluka Maiava were all listed for the linebacker position. The Los Angeles Times mentioned Ferrigno Jr. on the roster, but it was noted that he suffered a knee injury on the final play of spring practice in late March, 2006, was to have a knee surgery in April, and could be ready for the ’06 opener.

That didn’t really happen. He never played a down. Ferrigno’s time in the USC program, however, includes a time when Carroll allowed him to suit up and be one of the team captains before the Nov. 25 game against 10-1 Notre Dame at the Coliseum, which resulted in a 44-24 win.

The 2006 USC team was ranked No. 2 when it sustained a 13-9 loss at the Rose Bowl against the 6-5 UCLA team to knock itself out of the Bowl Champion Series title game. A 32-18 win over Michigan in the 2007 Rose Bowl left the Trojans ranked No. 4 overall at 11-2. And it gave Ferrigno a chance to say he was on a Rose Bowl title team.

Ferrigno Jr. got a degree in communications and a minor in business law by 2007. That’s when he diverted to acting, including improv comedy training.

After a few roles, Ferrigno Jr. was noticed in role as a firefighter Tommy Kinard in the TV series, “9-1-1.”

There is one other random connection with Ferrigno Jr., and USC, that recently surfaced.

Owen Hanson, a walk-on tight end himself out of Redondo High for a Carroll team in 2004, built a business called O-Dog Enterprises. He was arrested in Australia in 2015 on federal charges of gambling and drug trafficking, pleaded guilty and, in ‘17 was handed a 21-year prison sentence, and then tried to glamorize it all with a 2024 book, “The California Kid: From USC Golden Boy to International Drug Kingpin.”

In one part of the book, Hanson wrote:

“Maybe I needed a whole shitload of cash for a large shipment of cocaine that came dirt-cheap because the original buyers had gotten arrested in a sting and my people now had to move the product fast: I could ask for a one-month loan with 20 percent interest from Lou Ferrigno Jr., the movie star’s kid who would front it to me no questions asked. Of course, I’d make thirty grand off that loan in about a week.”

The Hanson bio is part of our post for No. 88. It’s not the blue print you’d want to present to anyone who had thoughts of walking on to any college sports team program.

Instead, maybe there’s a reality show based on this Instagram plea as a young man tries to get UCLA to allow him on a walk-on kicker:

Who else wore No. 59 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

Ismail Valdez, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1994 to 2000), Anaheim Angels pitcher (2001): A year after he won 13 games and posted a 3.05 ERA with two shutouts as a rookie in 1995, Valdez followed it with a 15-7 mark and 3.22 ERA in 33 starts at age 22. Yet in his seven MLB season career, including one back in L.A. after he was traded to the Chicago Cubs, Valdez shows just a 61-57 record and 3.48 ERA. He signed with the Anaheim Angels as a free agent in 2001. Perhaps Valdez’ most headline-worthy incident was in April of 1997 when he got into a shower-area altercation with teammate Eric Karros, who openly ridiculed Valdez in a team meeting for lasting just 3 1/3 innings, allowing eight hits and four runs in his worst start in two years.

Evan Phillips, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2021 to present): Picked up off waivers from Tampa Bay in August of 2021, Phillips had a 3-0 record and 0.00 ERA in 12 games covering five post-season series from ’21 to a World Series title in ’24. That included 21 strike outs in 15 1/3 innings. He struck out six of the 12 batters he faced in the ’21 NLCS versus Atlanta over three innings and fanned six of the 11 in the ’22 NLDS against San Diego. In five regular seasons with the Dodgers, Phillips compiled a 15-9 record with 45 saves in 78 games finished, a 2.22 ERA in 201 innings, with 221 strike outs over 195 innings (10.2 SO9 and 4.25 SO/BB ratio) for a 4.1 WAR. It has led to one of his nicknames listed on Baseball-Reference.com as “High Leverage Honey Bun.”

George Kase, UCLA football defensive tackle (1991 to 1995): A starter at nose guard as a sophomore and junior, the 6-foot-3, 250-pounder out of Hart High in Santa Clarita was moved to defensive tackle when UCLA went to a four-man front. He led the team in tackles for losses and sacks as a senior. Kase is one of only 19 players in the history of the UCLA-USC game to win five years in a row against his rival. He finished with 137 career tackles, 90 solo and 11 sacks. A three-time Academic All-American, he married USC swimming and diving coach Catherine Vogt in 2018.

Have you heard this story:

Mario Celotto, USC football linebacker (1974 to 1977): A St. Bernard High of Westchester graduate, born in L.A. and raised in Rancho Palos Verdes, Celotto was a 6-foot-3, 228-pound linebacker who got his moment in the spotlight for USC in the annual game against Notre Dame at South Bend, Ind. Early in the second quarter with Notre Dame pushed back to its own 4 yard line, Celotto grabbed a fumble in the air by Irish tailback Terry Eurick and ran it in five yards for a touchdown, the first points by USC in the contest, tying the game at 7-7. Douglas Looney described it in his Sports Illustrated account: Sure enough, with 10:44 to play in the half, Notre Dame’s Terry Eurick was popped hard on his own five, the ball squirted loose and USC Linebacker Mario Celotto grabbed it and took three steps into the end zone. The kick tied the score, and the feeling was in the air that No. 5-ranked USC was getting ready to demonstrate why it was No. 1 before losing to Alabama—and why it might well belong back at the top of the heap. But this was best known as the contest when Notre Dame head coach Dan Devine had the team come out to play in green uniforms and, ranked No. 11 behind Joe Montana, a third-string quarterback earlier in the fall, made a statement in crushing the Trojans, 49-19. A seventh-round pick by Buffalo in 1978, he was on Oakland’s Super Bowl XV team, and finished his career with the 1981 Los Angeles Rams (wearing No. 41). After retiring, he started the Humboldt Brewing Company.

Loek Van Mil, Los Angeles Angels relief pitcher (2011): At 7-foot-1, the Netherlands-born Van Mil was one of the tallest pitchers in professional baseball history. Some say he was the tallest. Tough to find anyone who could top that. After pitching his first four seasons in the Minnesota Twins organization, Van Mil came to the Angels in 2011 as the “player to be named later” in a deal involving reliever Brian Fuentes. Van Mil was invited to spring training, wearing No. 59, and made just one appearance before he was sent to Double-A Arkansas (where the 26-year-old was a teammate of 19-year-old Mike Trout). He started the 2012 season with the Angels’ Triple-A Salt Lake team before he was traded to Cleveland. Van Mil would pitch in Japan, for the Netherlands during the World Baseball Classic, and also in Australia. He suffered an odd death in 2019 at age 34, a year after after slipping, falling and hitting his head on rocks while bushwalking in Australia.

We also have:

Guillermo Mota, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (2002-to-’04, 2009)

Dan Dufour, UCLA football center (1980 to 1982)

Chuck Finley, California Angels pitcher (1986) Changed to No. 31 for the next 14 years of his Angels career.

Anyone else worth nominating?

1 thought on “No. 59: Collin Ashton and Lou Ferrigno Jr.”