This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 63:

= Booker Brown, USC football

= Joe Carollo, Los Angeles Rams

= Jim Brown, UCLA football

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 63:

= Mike McDonald, Los Angeles Rams

= Greg Horton, Los Angeles Rams

= Corey Linsley, Los Angeles Chargers

The most interesting story for No. 63:

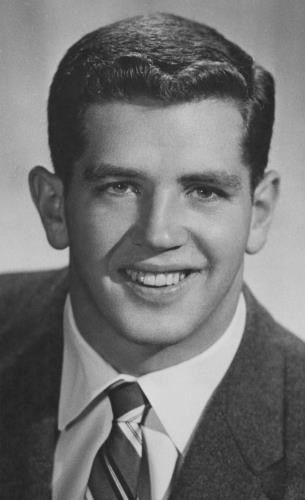

Jim Brown, UCLA football offensive lineman via L.A. Loyola High (1954 to 1955)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Los Angeles, Westwood, Glendale

Jim Brown helped make history, perhaps by accident, or by good fortune, as part of UCLA’s most unique 1954 national championship football team.

Decades later, Brown tackled an idea on how to preserve the team’s history, for the good fortune of those who came decades later.

A 6-foot, 204-pound right guard on an explosive line that paved the way for coach Red Sanders’ Single-Wing offense, Brown capped off a two-year run with the Bruins as an All-American in 1955. The teams he was on during his time went 18-2 and won two Pacific Coast Conference titles.

Sanders once referred to Brown as “one of the best football players we have had at UCLA. He has never played a poor game. As an all-around guard, he doesn’t back up from anyone. I haven’t seen anyone whip him yet across the scrimmage line. … In addition, you’ve never heard (Brown) complain or alibi or explain. He just goes out and gives his team the best he has.”

When Brown was inducted into the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame in 2001, it was noted that he also played rugby for the Bruins and was part of its ROTC program. Instead of signing with the NFL’s Chicago Cardinals, who drafted him in 1956, Brown went to the U.S. Army and became commissioned as a Second Lieutenant.

When Brown died at his home in Glendale in 2022 at age 87, survived by his wife of 66 years, Merrilyn, who was a UCLA song girl when they married in 1956, he took pride in having five children, 12 grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

Brown left not just his own life story, but those of his teammates from that Bruin era.

Check the final 1954 UPI coaches’ poll, and there’s UCLA’s 9-0 team ranked No. 1. The Bruins outscored opponents 367-40, capped off by throttling rival USC, 34-0, to end the regular season before more than 102,000 at the Coliseum. The Trojans net five total yards on the ground and endure five interceptions.

Braven Dyer of the Los Angeles Times wrote after UCLA throttled USC: “This is the best Bruin team I ever saw, and I’ve seen every one since the first Vermont Avenue outfit.”

Coming into the USC game, UCLA had won by scores such as 67-0 (the season opener against San Diego Navy), 72-0 (over Stanford and John Brodie, still a Bruins’ program record for margin of victory), 61-0 (at Oregon State) and 41-0 (vs. Oregon).

The team set program records for points in a season (with just nine games) and touchdowns in a season (55) and led the nation with scoring offense (40.8 a game) and scoring defense (4.4 a game).

The glitch in all this: The Bruins didn’t play in that season-ending Rose Bowl. A no-repeat rule was in place for the Pacific Coast Conference, which lasted eight years. The ’53 Bruins went 6-1 in the PCC title, then lost to Michigan, 28-20, at the Rose Bowl.

“They’re No. 1 in the nation as far as I’m concerned,” USC coach Jess Hill said after that ’54 season-ending loss to the Bruins.

Hence, the “best UCLA team that never played in a bowl game” became their title to wear.

Ohio State, voted No. 1 in the AP writers’ poll, represented the Big Ten in the Rose Bowl, squashed PCC-representative USC 20-7, and finished 10-0. The other major undefeated team in the nation that year, Oklahoma at 10-0, was No. 3 in both polls out of the Big Seven Conference.

It was a split decision. Not the first. Not the last. Just one that’s an ever-lasting thorn in the Bruins’ side.

Jim Brown, a Minnesota native, moved with his mother and sister to the Western/Wilshire area of Los Angeles after his father died in 1951. Brown spent his senior year at Los Angeles Loyola High, and the influence of the Jesuits led him to go to Santa Clara University to play football in 1952.

Brown admitted growing up in the Midwest he knew of the national recognition of USC’s football program, but UCLA wasn’t on his radar. Brown had been scouted by UCLA during a Loyola-Mt. Carmel High game, and the Bruins offered him a scholarship. Brown said he was overwhelmed by the size of the Westwood campus. Santa Clara felt less intimidating.

What he didn’t know is 1952 would be the final year of Santa Clara’s football program, as it had been struggling with a combined 8-18-2 since winning the 1950 Orange Bowl and finishing No. 15 in the AP poll. Santa Clara’s demise followed the disappearance of football at L.A.’s Loyola University (after the ’51 season) and Pepperdine University (dropped in ’61) in how the NFL’s move to the West Coast was taking away its football attention.

UCLA recruiters went up to Santa Clara to see if any players might want to find a new home. This time, Brown was on board. He brought along with him Jim Decker, who would turn out as a pivotal player in its UCLA’s offense with a team-best 508 rushing yards.

It seems rather unfair that NCAA rules at the time somehow required Brown and Decker to sit out a season as a transfer — even it was out of their control. So coming to UCLA as juniors on the 1954 team, a path to success was laid out by the defending PCC champs, which had most of its key players were coming off an 8-2 finish in ’53.

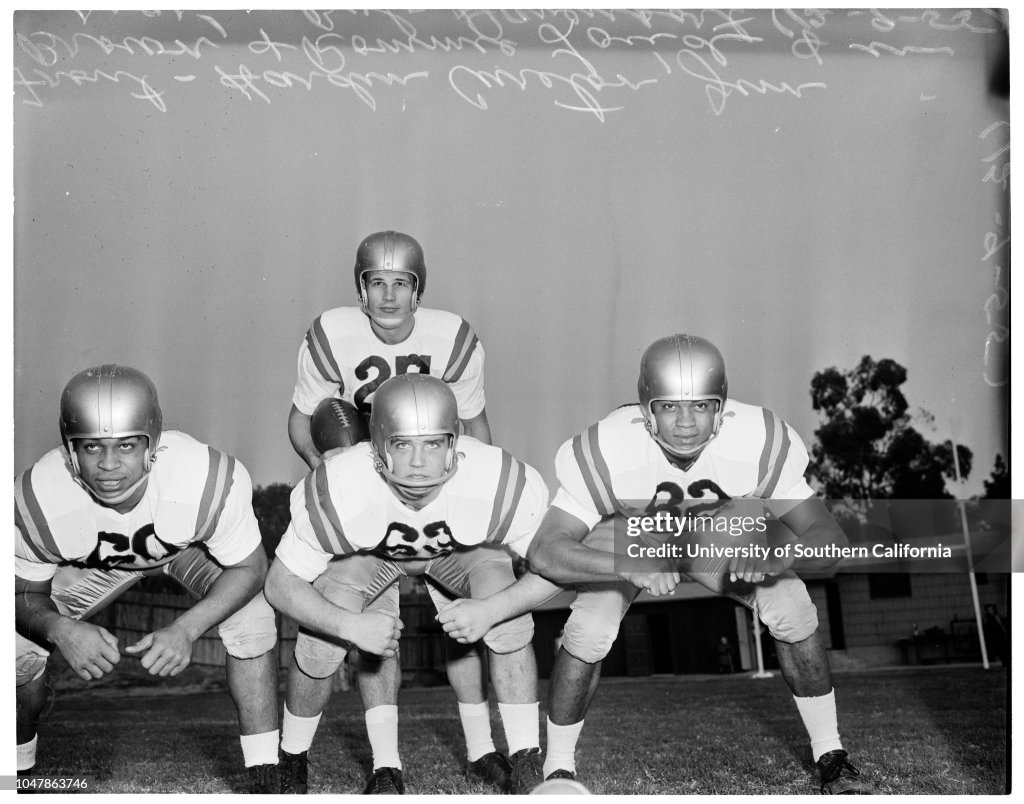

With future Bruins head coach Tom Prothro as the back coach and Jim Myers coaching the line, UCLA’s offense looked like a modern shot-gun formation. The ball was snapped to the tailback — in this case, All-American Primo Villanueva, known as “The Calexico Kid.” He was second to Decker with 479 yards rushing to go with 400 yards passing and five touchdowns. The fullback, All-American Bob Davenport from Long Beach, led the conference in scoring with 11 touchdowns. The quarterback, who did mostly blocking, was Terry Debay from Canoga Park High.

Newspapers writers who called the Sanders’ strategy a “horse-and-buggy offense” at the start of the season were referring to it as “hearse and buggy” before long for the way it overpowered defenses — even if they knew it was coming.

The key was UCLA’s offensive and defensive lines created All-American talent. Brown at first shared time with All-American Jim Salsbury. There was also Jack Ellena, Rommie Loudd and Hardiman Cureton. The center and captain was John Peterson out of L.A. University High. The defense included All-American Milt Davis, who had been discovered playing intramural flag football on the UCLA campus.

Gearing up for the 1955 season, the Bruins’ squad was pre-season No. 1 in the AP poll and squashed Texas A&M 21-0 in the season opener at the Coliseum. A 7-0 loss in Week 2 at No. 5 Maryland temporarily knocked UCLA to No. 7 in the polls, but the Bruins rattled off wins of 55-0 and 38-0 over Washington State and Oregon State. A 17-7 win over USC in the regular-season finale finished the Bruins’ regular season at 9-1 and capped an eight-game win streak. UCLA, now a three-time PCC winner and ranked No. 4, absorbed a 17-14 loss to No. 2 Michigan State in the 1956 Rose Bowl.

Brown considered a life in pro football as he went to the Senior Bowl in Mobile, Ala., but he decided to go into the service. He used his UCLA business major to get into the life insurance field, starting his own firm and working with his eldest son Ken for some 35 years.

During that time, Brown wast involved in planning team reunions. He loved the comradery and connective tissue that kept him and teammates in constant correspondence.

Before the ’54 team’s 50th reunion in 2004, Brown sent a simple questionnaire to his teammates. He asked:

1) Why did you come to UCLA?

2) How would you describe the experience?

3) What has been the effect of that experience and opportunity over your lifetime?

It became the framework of a somewhat modest 2006 book, “To Know A Man, Know His Memories.”

When Brown was named as an honorary captain for the UCLA football team prior to its 2006 season Week 2 home game against Rice, a 26-16 win that marked the 50th anniversary of his last season, he alluded to the book coming out.

“Nobody will read it, but somebody who’s on the team, but that’s all that matters,” he said.

Among the things the book revealed and revived:

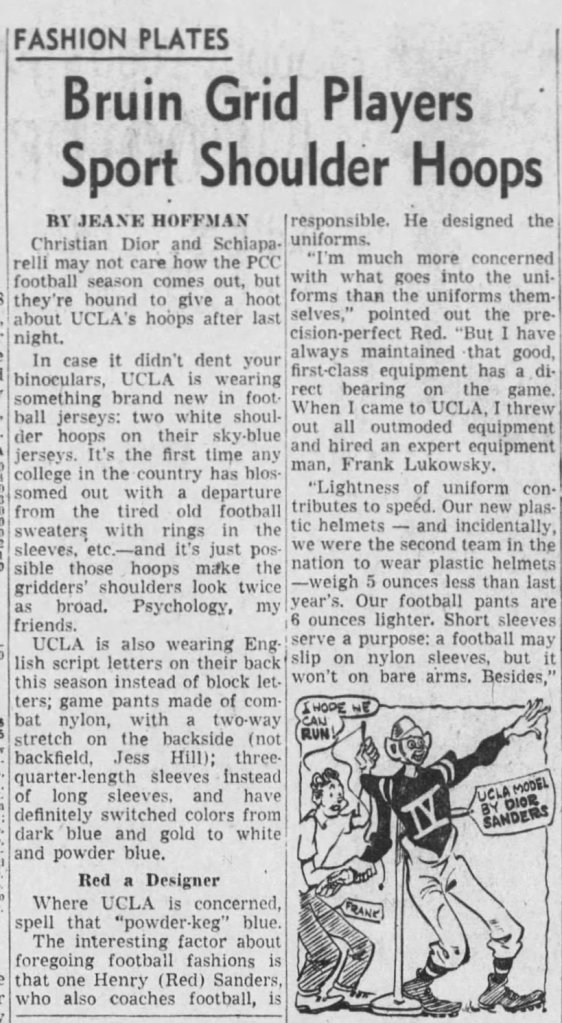

= 1954 was the first time UCLA football wore power blue jerseys with two white shoulder hoops on the shoulders. They included the khaki colored pants and English script letters and numbers. No more Navy blue and gold as the program inherited from UC Berkeley. The UCLA helmets were also now made of updated plastic, five ounces lighter. It was a team built for the future.

Brown even referenced a story by Los Angeles Times sportswriter/illustrator Jeane Hoffman that started: “Christian Dior and Schiaparelli may not care how the PCC football season comes out, but they’re bound to give a hoot about UCLA’s hoops after last night. … Where UCLA is concerned, spelled that ‘powder-keg’ blue.”

= Brown noted that “the newspapers always attempted to play the ‘race card’ by continually pointing out the southern origins of the (UCLA) coaches (as Sanders and his staff had come from Vanderbilt in Tennessee). I don’t remember any players of color on any other Pacific Coast Conference team in 1954, certainly none at USC, Cal or Stanford.

“One racial incident did occur on a trip to the University of Kansas in 1954 (the team’s first road trip in late September, a 32-7 Bruin win). We stayed at a hotel in Kansas City. Arriving late, a few players went to the hotel restaurant to have something to eat. The group consisted of several black and white players. The manager of the restaurant came over and notified the group that they could serve food to the white players but not the black players and the black players would have to leave. He somehow seemed to think that would be acceptable.

“Sam Boghosian took the leadership and not so quietly informed the manager that ‘we’re all out of here’.”

= John Odabashain, the UCLA senior team manager of the team, Brown’s roommate for three seasons, and the best man at his wedding, wrote:

“The single most important experience that I still carry, that I do not think I would have had any place else, has to do with the interaction and tolerance for and with people of difference races and religions. … The idea that we are all alike and that one can make and keep friends through humor has served me well.”

An offensive line is a band of brothers. All different backgrounds, races, sizes. With the same goal.

Jim Brown embraced that idea at UCLA.

In Brown’s Legacy.com obituary, it celebrated how he was a successful businessman in the financial world for 60 years because of his “trademark optimism and unbridled energy.” He “loved to see people thrive, and touched the lives of many across all generations through his hands-on activism and generous support of dozens of youth, spiritual and charitable organizations.” He was “passionate about golf, ice cream, movies, Palm Springs and barbecuing for big congregations. Above all, Jim cherished his family, as noted by the Glendale News Press, which named him Father of the Year in 1975.”

Near the start of the book, Brown wrote:

“I had never heard of UCLA in 1951 and yet by 1954 I was a member of their first, and only, national championship football team and on a life track that I never could have imagined. I am not considered too religiously off the wall, I simply refer to this odd series of events as divine coincidence.”

To end his book, Brown wrote in the conclusion:

“(1976 UCLA head football coach Dick) Vermeil spoke of short episodes in life that are particularly prevalent in sports; where a group of athletes share an experience that binds them for life. UCLA’s 1954 football (team) is one of those ‘spots of time.’ I believe the key to happiness is gratefulness — regardless of the circumstances, and I am truly grateful.”

Who else wore No. 63 in SoCal sports history? Make a case for:

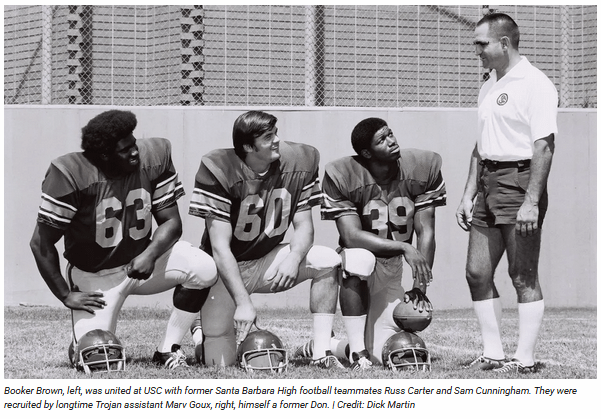

Brooker Brown, USC football offensive lineman (1972 to 1973):

At Santa Barbara High, Brown played football with Sam Cunningham, along with basketball and baseball, and then spent two years at Santa Barbara City College before transferring to USC. The 6-foot-2, 250-pounder took advantage of playing opportunity due to injuries and became a starter on the Trojans’ 1972 national championship team, again with Cunningham diving over his blocks to score. As a senior, he was a consensus first-team All-American and won USC’s Lineman of the Year Award in 1973. Although he was a sixth-round pick of the Houston Oilers in the 1974 NFL draft, Brown played for the World Football League’s Southern California Sun, along with USC teammates Anthony Davis and Pat Haden. When the league folded, Brown went to San Diego and then was traded to Tampa Bay, reunited with coach John McKay. His induction into the Santa Barbara High Athletic Hall of Fame in 2019 noted his post-playing days as a pastor, living in Mojave. He died in 2020.

Joe Carollo, Los Angeles Rams offensive left tackle (1962 to 1968, 1971): A Pro Bowl selection with the the Rams in 1968, Carollo started 131 of 132 games from ’63 to ’70, which included two years in Philadelphia.

Mike McDonald, Los Angeles Rams outside linebacker (1983 to 1991): From Burroughs High in Burbank and USC, the 6-foot-1, 238-pounder. Changed to No. 90 in 1986-91 when he was a long snapper.

Greg Horton, Los Angeles Rams offensive guard (1976 to 1978, 1980): A 6-foot-4, 245-pounder born in San Bernardino and out of Redlands High known as “Guns.”

Corey Linsley, Los Angeles Chargers center (2021 to 2023): After his first seven years as the Green Bay Packers’ starting center, he came to the Chargers at age 30 and was a Pro Bowl selection, starting 33 games for the team.

Anyone else worth nominating?

Note: Gene Upshaw, Oakland Raiders offensive guard (1967 to 1981) and Barret Robbins, Oakland Raiders center (1995 to 2003) are worth noting, but made their marks before and after the Raiders’ time in Los Angeles.

1 thought on “No. 63: Jim Brown”